Abstract

We report here a ligation-based spoligotyping that can identify unamplified spacers in membrane-based spoligotyping due to asymmetric insertion of IS6110 in the direct repeat locus. Our typing yielded 84.4% (411/487) concordance with traditional typing and 100% (487/487) accuracy when confirmed by DNA sequencing.

TEXT

Spacer oligonucleotide typing (spoligotyping) is a widely used PCR-based method for genotyping Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC) organisms (1, 2). It detects the presence or absence of 43 unique spacers in the direct repeat (DR) region of MTBC by a reverse line blot hybridization approach (3). This method forms the base for the development of publicly available strain databases, such as SITVITWEB (4) and MIRU-VNTRplus (5). Alternative detection formats were also proposed, including microbead technology (6–8), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (9), microarray (10–13), etc. Despite the varied endpoint detections and improved throughput, the starting step of spoligotyping, i.e., PCR using the DR-derived primers, remains unchanged.

It is noted, however, that the DR region is a hot spot for insertion of the IS6110 element in members of the MTBC (14, 15). A single IS6110 transposition event in the DR region could disrupt one of the spoligotyping primer regions, resulting in unamplified spacers and changes in the spoligotype pattern (16–18). We previously developed a two-dimensional (2D)-labeling strategy for probe amplification that allows multiple targets to be detected in a single reaction (19). We speculated that such a probe amplification strategy without DR primers might obviate the insertion problem. In this study, we used the probe strategy to develop a DR-free spoligotyping approach and to evaluate whether it could detect those spacers that failed to be amplified by current methods.

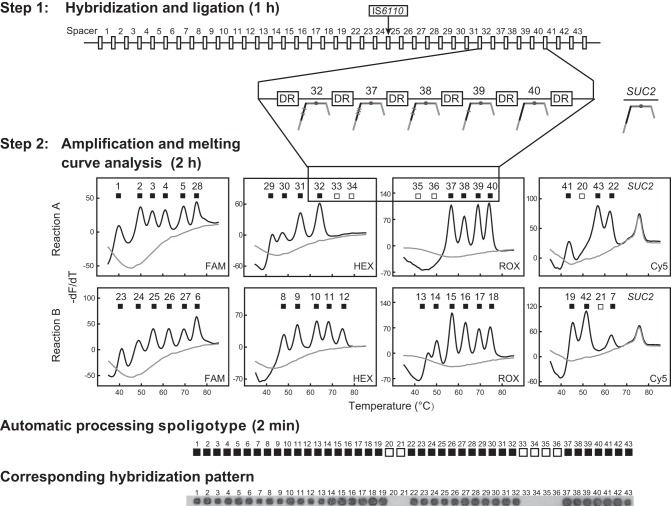

A schematic diagram of our ligation-based 2D-spoligotyping protocol is presented in Fig. 1. Two oligonucleotides are hybridized to one spacer and ligated to one another, forming an intact DNA template for PCR amplification. After PCR, melting curve analysis generates distinct melting temperature (Tm) values at predefined fluorescence channels corresponding with different spacers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). This two-reaction assay covers all 43 spacers and the SUC2 gene as an external positive control (EPC). We chose M. tuberculosis H37Rv and Mycobacterium bovis BCG as model strains to demonstrate the feasibility of 2D-spoligotyping, as they together possess all 43 spacers used for conventional spoligotyping. Under the experimental conditions described in the supplemental material, both H37Rv and BCG displayed their respective spacers (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Schematic illustration of 2D-spoligotyping assay. In step 1, the two hybridization probes targeted the present spacer specifically and ligated. In step 2, the ligation products would be amplified and followed by melting curve analysis. The SLAN-96 autoanalyzer system can identify the positive peaks and negative peaks at predefined Tm positions and automatically output a 43-digit binary code, where ■ indicates the presence of the corresponding spacer, and □ indicates its absence. FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein.

The presence or absence of the melting peaks could be interpreted using a 43-digit binary code corresponding with the spoligotype by the SLAN-96 system used in this study. A prerequisite for this interpretation is a rule to distinguish the positive peaks from the negative ones. To develop this rule, we used a set of 35 MTBC strains of various spoligotypes and 11 nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) that had only negative peaks. For each positive spacer, we recorded the peak height and calculated the mean value, the minimal height, and the maximal height. For the negative spacers, we recorded the noise data at the positive-peak position and calculated the mean value and three times the standard deviation (SD). By setting the average value of the negative data plus three times the SD as the cutoff value, a clear distinction between the positive spacers and negative spacers could be obtained (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The limit of detection was studied using genomic DNA of H37Rv and BCG at different concentrations. The results showed that repeated positive peaks were obtained when the genomic DNA concentration was ≥1 × 104 genomes/μl (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Such a limit of detection was sufficient for cultured MTBC samples that often contain >105 bacteria per μl.

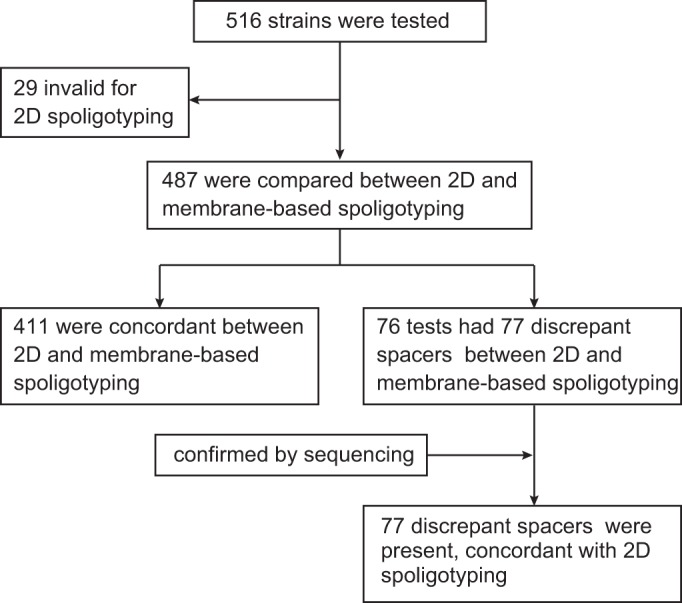

To evaluate the validity of 2D-spoligotyping, 516 DNA samples stored at the Public Health Research Institute (PHRI), NJ, that had previously been spoligotyped on membranes were typed in a blinded fashion (Fig. 2). Twenty-nine samples were invalid in the 2D-spoligotyping assay due to the low concentration of DNA. DNA sequencing analysis was used to confirm samples with discrepant outcomes between our method and the conventional spoligotyping method. Our assay identified 184 spoligotypes representing 11 major clades (Beijing, T, Haarlem, East-African Indian [EAI], Latin-American Mediterranean [LAM], Central Asian strain [CAS], Bovis, S, X, Manu, and AFRI) in the public database (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The concordance rates between the two typing methods were 84.4% (411/487) on the sample level and 99.6% (20,864/20,941) on the spacer level. Among 76 samples that showed discordance between the two methods, DNA sequencing results showed that all 77 spacers detected as positive by our method indeed existed, demonstrating that asymmetric IS6110 insertion in the DR might have caused the failure to detect the spacers by conventional spoligotyping.

FIG 2.

Summary of clinical MTBC strains used in this study compared by 2D-spoligotyping and traditional membrane-based spoligotyping.

Sequencing analysis further revealed the distribution of the IS6110 insertion among different spoligotypes and the exact insertion sites in the DR region (Table 1). The insertions were detected in 34 spoligotypes among nine clades/subclades (T1, T2, CAS, CAS1-Delhi, CAS2, H1, H3, Beijing, and X3), indicating the widespread nature of the IS6110 insertion in DRs regardless of spoligotype. Also, it seemed that IS6110 insertion sites were randomly dispersed along the entire DR region. The most frequent insertion site was found between the 6th and 7th nucleotides (from left to right, sic passim) in the DR, flanked by spacers 31 and 25. This insertion site was present in 33 (43.4%) samples involving 15 spoligotypes with 14 of the H3 subclade and one undefined spoligotype. The second common insertion site was found between 27th and 28th nucleotides within spacer 23, involving 14 (18.4%) samples that represent 8 shared types (SITs) in the CAS clade (six SITs of CAS1-Delhi, one CAS, and one CAS2). With the exception of the insertion in the DR between spacers 36 and 37, which accounts for 18 (23.7%) samples, the other 11 insertion sites were found only in one sample each. Surprisingly, some spacers (e.g., spacers 14, 23, and 39) also became the target of insertion, implying that although IS6110 insertion preferentially targets DR sites, it can sometimes insert into the spacer region.

TABLE 1.

Discrepant spacers and IS6110 insertion sites in 76 samples

| Spacer(s) (n)a | IS6110 insertion site in spacer sequenceb | SIT (clade)c |

|---|---|---|

| 5 (1) | Spacer 4-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGIS6110 ←GAAAC-spacer 5 | Orphan (T1) |

| 8 (1) | Spacer 7-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGIS6110←GGACGGAAAC-spacer 8 | Orphan (ND) |

| 8 (1) | Spacer 8-(DR)GIS6110←TCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 9 | 266 (T1) |

| 14 (1) | DR-(spacer 14)TTGCGCIS6110←CAACCCTTTCGGTGTGATGCGGATGGTCGGCTCGG-DR | 1230 (H1) |

| 17 (1) | Spacer 16-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGAIS6110←CGGAAAC-spacer 17 | Orphan (T2) |

| 22 (1) | Spacer 21-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGIS6110→GGACGGAAAC-spacer 22 | ND (ND) |

| 21, 23 (1) | Spacer 21-(DR)GTIS6110←CGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 22-DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 2145 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 23 (7) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 26 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 381 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 141 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 1551 (CAS) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 247 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 288 (CAS2) |

| 23 (1) | DR-(spacer23)CCTCAGCTCAGCATCGCTGATGCGGTCIS6110→CAGCTCGTCCGT-DR | 2733 (CAS1-Delhi) |

| 31 (18) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 50 (H3) |

| 31 (3) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 49 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 1136 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 1159 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 2077 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 2213 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 294 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 3 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 36 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 457 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 512 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | 746 (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | Orphan (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacer 25, 32 | Orphan (H3) |

| 31 (1) | Spacer 31-(DR)GTCGTCIS6110→AGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAAC-spacers 25, 26, 37 | ND (ND) |

| 37 (18) | Spacer 36-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGIS6110→GAAAC-spacer 37 | 265 (Beijing) |

| 37 (1) | Spacer 33-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGIS6110→GAAAC-spacer 37 | 27 (ND) |

| 38 (1) | Spacer 37-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGIS6110←AAAC-spacer 38 | Orphan (T1) |

| 39 (1) | Spacer 24-(DR)GTCGTCAGACCCAAAACCCCGAGAGGGGACGGAAIS6110→AC-spacer 39 | ND (ND) |

| 39 (1) | DR-(spacer 39)CCGACGAIS6110←TGGCCAGTAAATCGGCGTGGGTAACCGATCCGG-DR | 70 (X3) |

n, number of strains containing the same discrepant spacer in one spoligotype.

The direction of arrow indicates the orientation of the IS6110 insertion.

SIT/clade obtained from SITVITWEB database. ND, not defined SIT or clade in SITVITWEB database.

The above-described results supported our prediction that our ligation-based 2D-spoligotyping approach could not only correctly detect spoligotypes when IS6110 is absent in the DR and spacer regions, but it could also reveal the existence of correct spacer types even when asymmetric IS6110 insertion in the DR or inside a spacer interferes with the conventional spoligotyping method. SpolSpred (20), which is a software that allows the extraction of spoligotyping from raw sequence reads, would provide the same results with 2D-spoligotyping in the case of the 76 discordant samples. This unique feature should increase the discrimination power of spoligotyping. Meanwhile, the absence of melting curves on any positive-peak position with different NTM isolates demonstrated that the assay was specific for MTBC. Moreover, the decreased turnaround time and closed-tube detection would also help process a large number of samples with low chance for carryover contamination of the amplicons. Finally, the cost of reagent for each sample is roughly the same as that in a membrane-based approach. Thus, our newly established typing method can both substitute the traditional spoligotyping assay with high concordance and reveal spacers that are undetectable by conventional spoligotyping method due to asymmetric IS6110 insertion inside or nearby the spacers that were missed by conventional detection.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China 863 Program (grant 2014AA021401) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81271929).

We thank the National Institute for Food and Drug Control (Beijing, China) for providing MTBC standard strains and NTM isolates.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00857-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brudey K, Driscoll JR, Rigouts L, Prodinger WM, Gori A, Al-Hajoj SA, Allix C, Aristimuño L, Arora J, Baumanis V, Binder L, Cafrune P, Cataldi A, Cheong S, Diel R, Ellermeier C, Evans JT, Fauville-Dufaux M, Ferdinand S, Garcia de Viedma D, Garzelli C, Gazzola L, Gomes HM, Guttierez MC, Hawkey PM, van Helden PD, Kadival GV, Kreiswirth BN, Kremer K, Kubin M, Kulkarni SP, Liens B, Lillebaek T, Ho ML, Martin C, Martin C, Mokrousov I, Narvskaïa O, Ngeow YF, Naumann L, Niemann S, Parwati I, Rahim Z, Rasolofo-Razanamparany V, Rasolonavalona T, Rossetti ML, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Sajduda A, Samper S, Shemyakin IG, et al. 2006. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex genetic diversity: mining the fourth international spoligotyping database (SpolDB4) for classification, population genetics and epidemiology. BMC Microbiol 6:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pang Y, Song Y, Xia H, Zhou Y, Zhao B, Zhao Y. 2012. Risk factors and clinical phenotypes of Beijing genotype strains in tuberculosis patients in China. BMC Infect Dis 12:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamerbeek J, Schouls L, Kolk A, van Agterveld M, van Soolingen D, Kuijper S, Bunschoten A, Molhuizen H, Shaw R, Goyal M, van Embden J. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J Clin Microbiol 35:907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demay C, Liens B, Burguière T, Hill V, Couvin D, Millet J, Mokrousov I, Sola C, Zozio T, Rastogi N. 2012. SITVITWEB–a publicly available international multimarker database for studying Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology. Infect Genet Evol 12:755–766. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weniger T, Krawczyk J, Supply P, Niemann S, Harmsen D. 2010. MIRU-VNTRplus: a Web tool for polyphasic genotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 38:W326–W331. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowan LS, Diem L, Brake MC, Crawford JT. 2004. Transfer of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotyping method, spoligotyping, from a reverse line-blot hybridization, membrane-based assay to the Luminex multianalyte profiling system. J Clin Microbiol 42:474–477. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.474-477.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ocheretina O, Merveille YM, Mabou MM, Escuyer VE, Dunbar SA, Johnson WD, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. 2013. Use of Luminex MagPlex magnetic microspheres for high-throughput spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. J Clin Microbiol 51:2232–2237. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00268-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Abadia E, Refregier G, Tafaj S, Boschiroli ML, Guillard B, Andremont A, Ruimy R, Sola C. 2010. Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex CRISPR genotyping: improving efficiency, throughput and discriminative power of ‘spoligotyping’ with new spacers and a microbead-based hybridization assay. J Med Microbiol 59:285–294. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.016949-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honisch C, Mosko M, Arnold C, Gharbia SE, Diel R, Niemann S. 2010. Replacing reverse line blot hybridization spoligotyping of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J Clin Microbiol 48:1520–1526. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02299-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song EJ, Jeong HJ, Lee SM, Kim CM, Song ES, Park YK, Bai GH, Lee EY, Chang CL. 2007. A DNA chip-based spoligotyping method for the strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. J Microbiol Methods 68:430–433. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruettger A, Nieter J, Skrypnyk A, Engelmann I, Ziegler A, Moser I, Monecke S, Ehricht R, Sachse K. 2012. Rapid spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria by use of a microarray system with automatic data processing and assignment. J Clin Microbiol 50:2492–2495. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00442-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bespyatykh JA, Zimenkov DV, Shitikov EA, Kulagina EV, Lapa SA, Gryadunov DA, Ilina EN, Govorun VM. 2014. Spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates using hydrogel oligonucleotide microarrays. Infect Genet Evol 26:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabibbe AM, Miotto P, Moure R, Alcaide F, Feuerriegel S, Pozzi G, Nikolayevskyy V, Drobniewski F, Niemann S, Reither K, Cirillo DM, TM-REST Consortium, TB-CHILD Consortium. 2015. Lab-on-chip-based platform for fast molecular diagnosis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 53:3876–3880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang Z, Morrison N, Watt B, Doig C, Forbes KJ. 1998. IS6110 transposition and evolutionary scenario of the direct repeat locus in a group of closely related Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. J Bacteriol 180:2102–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Embden JDA, van Gorkom T, Kremer K, Jansen R, van der Zeijst BAM, Schouls LM. 2000. Genetic variation and evolutionary origin of the direct repeat locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. J Bacteriol 182:2393–2401. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.9.2393-2401.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filliol I, Sola C, Rastogi N. 2000. Detection of a previously unamplified spacer within the DR locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: epidemiological implications. J Clin Microbiol 38:1231–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benjamin WH Jr, Lok KH, Harris R, Brook N, Bond L, Mulcahy D, Robinson N, Pruitt V, Kirkpatrick DP, Kimerling ME, Dunlap NE. 2001. Identification of a contaminating Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain with a transposition of an IS6110 insertion element resulting in an altered spoligotype. J Clin Microbiol 39:1092–1096. doi: 10.1128/JCM.37.3.1092-1096.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Legrand E, Filliol I, Sola C, Rastogi N. 2001. Use of spoligotyping to study the evolution of the direct repeat locus by IS6110 transposition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 39:1595–1599. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1595-1599.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao Y, Wang X, Sha C, Xia Z, Huang Q, Li Q. 2013. Combination of fluorescence color and melting temperature as a two-dimensional label for homogeneous multiplex PCR detection. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e76. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coll F, Mallard K, Preston MD, Bentley S, Parkhill J, McNerney R, Martin N, Clark TG. 2012. SpolPred: rapid and accurate prediction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis spoligotypes from short genomic sequences. Bioinformatics 28:2991–2993. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.