Abstract

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) of samples from 15 patients with documented Zika virus (ZIKV) infection in Bahia, Brazil, from April 2015 to January 2016 identified coinfections with chikungunya virus (CHIKV) in 2 of 15 ZIKV-positive cases by PCR (13.3%). While generally nonspecific, the clinical presentation corresponding to these two CHIKV/ZIKV coinfections reflected infection by the virus present at a higher titer. Aside from CHIKV and ZIKV, coinfections of other viral pathogens were not detected. The mNGS approach is promising for differential diagnosis of acute febrile illness and identification of coinfections, although targeted arbovirus screening may be sufficient in the current ZIKV outbreak setting.

INTRODUCTION

Zika virus (ZIKV), a flavivirus, and chikungunya virus (CHIKV), an alphavirus, are infectious RNA arboviruses transmitted to humans by the bite of Aedes species mosquitoes. Both viruses have only recently emerged in the Western Hemisphere (1, 2), and along with dengue virus (DENV), another flavivirus, now circulate widely in Brazil. The acute illness caused by these viruses, characterized by fever, rash, myalgia, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis, is nonspecific, and differential diagnosis on the basis of clinical findings alone is challenging. Later infectious sequelae include chronic arthritis for CHIKV (2) and encephalitis, immune-mediated syndromes, and stroke for DENV (3). Recently, the association between ZIKV infection and severe fetal complications such as microcephaly in pregnant women has been established (4), and the virus has also been linked to neurological complications such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (5). Thus, broad-based assays are needed for differential diagnosis of vector-borne febrile illnesses and to identify potential coinfections. Here we report the utility of metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) as a screening tool to identify coinfections and the use of genome recovery and phylogenetic analyses directly from patient serum samples in the context of the ongoing ZIKV outbreak. We also show that the clinical presentation of arboviral coinfections seems to favor the virus present at a higher titer in acutely infected individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ZIKV serum sample collection, ZIKV RT-PCR, and DENV antibody testing.

Written consent from patients was obtained under a study protocol approved by the Brazil Ministry of Health (Certificado de Apresentação para Apreciação Ética 45483115.0.0000.0046, no. 1159.184, Brazil). Serum samples were obtained from 15 patients seen at Aliança Hospital in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, from April 2015 to January 2016 who were given a presumptive diagnosis of an acute viral illness by emergency department physicians and were found to be positive by qualitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) testing for ZIKV. Serum samples Bahia01 to Bahia15 were subjected to RNA extraction using the QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen), and RNA was reverse transcribed using the Superscript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen), followed by qualitative RT-PCR testing for ZIKV using primers targeting the NS5 gene (6). Serum samples were also tested for DENV infection using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) specific for the NS1 antigen and anti-DENV IgG/IgM according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dengue Duo Test; Bioeasy Diagnostica, Brazil).

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing.

A separate serum aliquot was extracted for total nucleic acid using the Qiagen viral RNA minikit (Qiagen), followed by DNase treatment using a cocktail of Turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Baseline-Zero DNase (Epicentre Biotechnologies), followed by NGS library construction using the NexteraXT kit (Illumina) as previously described (7, 8). Runs of single-end, 160-base pair (bp) dual-indexed mNGS libraries were performed on an Illumina MiSeq instrument. To minimize flow cell cross-contamination during sequencing, a ZIKV PCR-positive sample known to have a high titer of ZIKV was sequenced independently from the other samples in a separate run. The metagenomic data were scanned for any reads corresponding to known pathogens using the SURPI (sequence-based ultrarapid pathogen identification) computational pipeline (9).

Confirmatory CHIKV RT-PCR testing.

Confirmatory RT-PCR testing for chikungunya virus was performed using a qualitative nested RT-PCR assay targeting the E2 gene as previously described (10, 11). PCR primers and assay conditions were identical to those outlined in reference 11, except that the 25 μl master mix was taken from the Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). A presumptive ZIKV/CHIKV coinfection identified by mNGS was considered established only if confirmed by positive CHIKV RT-PCR test results from the original extract (10, 11).

Determination of ZIKV titers.

To quantify ZIKV viremia, a standard curve was established, and repeat ZIKV PCR testing of the 15 patient serum samples was performed using a SYBR green quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) assay with primers targeting the envelope gene (ZIKV-1086/ZIKV-1162) (12).

DENV RT-PCR testing.

RNA testing of the 15 patient serum samples for DENV was performed using a previously published nested RT-PCR assay (13). Both first-round and second-round PCR amplicons were visualized by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and bands of expected size were extracted from the gel and sequenced by Sanger sequencing. DENV RT-PCR testing of the 15 serum samples in this study yielded only one band in a single sample that was sequenced and found to correspond to Aedes aegyptii mosquito genome.

Capture probe enrichment.

To aid genome recovery of sample Bahia08, we enriched the mNGS library for ZIKV sequences using a set of 299 XGen biotinylated lockdown capture probes (IDT Technologies) targeting all ZIKV genomes in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) GenBank database, as previously described (14), followed by Illumina MiSeq sequencing of the enriched library. Enrichment was performed using the XGen lockdown protocol and SeqCap EZ Hybridization and Wash kit (Roche Molecular Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Using the MAFFT program in Geneious, all 43 ZIKV genome sequences available in NCBI GenBank as of March 2016 and 13 CHIKV sequences from the East/Central/South African (ECSA) clade were aligned together with 3 ZIKV complete or partial genomes and 2 CHIKV complete or partial genomes recovered in the current study. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, followed by refinement using the MrBayes algorithm at default settings in the Geneious software package (Biomatters, Inc.).

Accession numbers.

NGS reads with human sequences removed have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (accession number PRJNA329512; umbrella accession number PRJNA315767). The three ZIKV genome sequences and two CHIKV genome sequences have been deposited in NCBI GenBank (accession numbers KU940224, KU940227, and KU940228 for the ZIKV genomes and KU940225 and KU940226 for the CHIKV genomes).

RESULTS

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing of ZIKV serum samples.

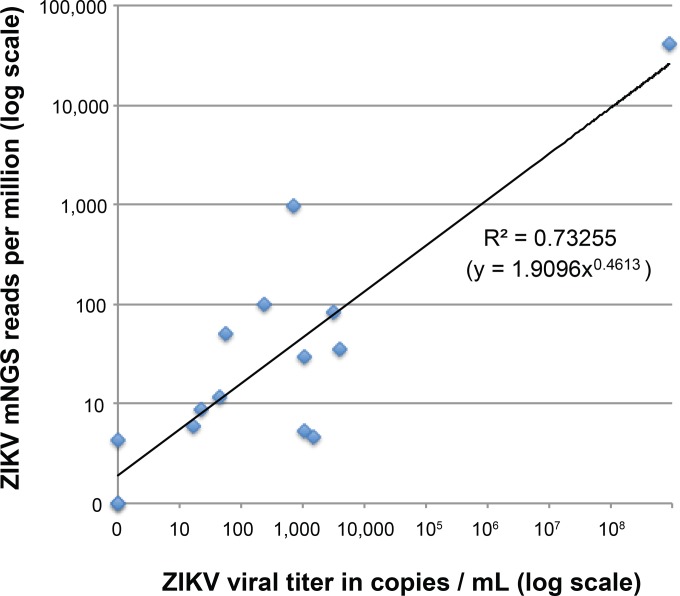

Serum samples were collected from 15 patients within 5 days of the onset of symptoms and at the first visit seen during an ongoing ZIKV outbreak at Aliança Hospital in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, from April 2015 to January 2016 (15). All 15 patients tested positive for ZIKV by RT-PCR and negative for DENV by serology. Between 24,063 and 6,903,397 mNGS reads were generated per sample, and reads aligning to ZIKV were identified in 13 of 15 (86.7%) ZIKV-positive samples (positive by PCR) (Table 1). Two ZIKV PCR-positive samples (Bahia13 and Bahia14) were negative for ZIKV reads by mNGS, and both exhibited low viral titers by qRT-PCR (<30 copies/ml and 517 copies/ml, respectively) (Table 1). A log-log plot of ZIKV mNGS reads (in reads per million [RPM]) against viral titer revealed a moderate correlation, with a log R2 value of 0.73255 (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

ZIKV and CHIKV testing of 15 PCR-positive ZIKV cases in Bahia, Brazil, from April 2015 to January 2016a

| Sample | Test result before mNGS |

Metagenomic next-generation sequencing |

Test result after mNGS |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIKV RT-PCRb | DENV Ab | No. of raw reads | No. of ZIKV reads | % ZIKV reads | ZIKV mNGS (run 1/run 2) | % ZIKV coverage | No. of CHIKV reads | % CHIKV reads | CHIKV mNGS (run 1/run 2) | % CHIKV coverage | CHIKV RT-PCR | ZIKV qRT-PCRc | ZIKV viral load (no. of copies/ml) | DENV RT-PCR | |

| Bahia01 | + | − | 3,507,376 | 103 | 0.003 | +/+ | 34.1 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 1,042 | − |

| Bahia02 | + | − | 3,668,673 | 129 | 0.003 | +/+ | 39.5 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 4,086 | − |

| Bahia03 | + | − | 24,063 | 2 | 0.008 | +/+ | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 3,272 | − |

| Bahia04 | + | − | 3,060,229 | 14 | 0.0005 | +/+ | 9.6 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 1,464 | − |

| Bahia05 | + | − | 3,501,316 | 19 | 0.0005 | +/+ | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 1,091 | − |

| Bahia06 | + | − | 2,576,002 | 11 | 0.0004 | +/+ | 5.4 | 4 | 0.0002 | +/+ | 1.1 | − | − | <31 | − |

| Bahia07 | + | − | 6,903,397 | 281,099 | 4.1 | + | 100.0 | 0 | 0 | − | 0.0 | − | + | 9.00E+08 | − |

| Bahia08 | + | − | 1,094,355 | 55 | 0.005 | + | 35.1 | 252,649 | 23.1 | + | 100.0 | + | + | 2,470 | − |

| Bahia09 | + | − | 743,266 | 719 | 0.1 | + | 97.6 | 84 | 0.01 | + | 49.1 | + | + | 23,121 | − |

| Bahia10 | + | − | 2,482,665 | 22 | 0.0009 | +/+ | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | − | <31 | − |

| Bahia11 | + | − | 2,384,416 | 234 | 0.01 | +/+ | 40.9 | 37 | 0.002 | +/+ | 8.6 | − | + | 3,981 | − |

| Bahia12 | + | − | 3,712,405 | 44 | 0.001 | +/+ | 21.3 | 23 | 0.0006 | +/+ | 9.8 | − | + | 1,327 | − |

| Bahia13 | + | − | 2,556,556 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | 1 | 0 | +/− | 1.4 | − | − | <31 | − |

| Bahia14 | + | − | 3,658,143 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | + | 517 | − |

| Bahia15 | + | − | 2,848,486 | 17 | 0.001 | +/+ | 7.9 | 0 | 0 | −/− | 0.0 | − | − | <31 | − |

FIG 1.

Log-log plot of detected ZIKV reads against viral titer. The number of mNGS reads is normalized to reads per million (RPM) of raw reads sequenced. A power trendline is fitted to the data, showing an R2 correlation of 0.73255.

Reads aligning to CHIKV were detected in 6 of 15 (40.0%) ZIKV-positive samples. Given the possibility of cross-contamination from a previously unknown high-titer CHIKV sample (Bahia08), the mNGS run was repeated after removing this sample library. However, the repeat run still resulted in detection of CHIKV reads in 5 of 15 (33.3%) samples. Since we could not reliably distinguish between mNGS library cross-contamination versus low-level metagenomic detection near the limits of detection for RT-PCR, a coinfection with CHIKV was considered established only if it was independently confirmed by orthogonal testing using a CHIKV nested RT-PCR (10, 11). Using this criterion (both mNGS and RT-PCR positivity for CHIKV), 2 of 15 (13.3%) ZIKV-positive samples (Bahia08 and Bahia09) were designated as CHIKV/ZIKV coinfections. Aside from ZIKV and CHIKV, apparent coinfections from other viral pathogens associated with acute febrile illness were not detected. Additional viral reads detected in the mNGS data were sparse and were attributed to known commensals (e.g., human pegivirus 1, papillomaviruses), viruses with nonhuman hosts (e.g., phage, insect viruses), or laboratory contamination due to detection in unrelated mNGS data sets (e.g., adenovirus, rotavirus, polyomavirus) (Table 2). Notably, no mNGS reads aligning to DENV were detected, and DENV RT-PCR testing of all 15 samples was also negative (Table 1).

TABLE 2.

Reads in the metagenomic sequencing data corresponding to other viruses aside from CHIKV and ZIKVa

| Viral species or genus | No. of reads | No. of samples | Explanation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human mastadenovirus A | 1 | 1 | Suspected lab contaminantb |

| Human pegivirus 1 (GBV-C) | 1,710 | 1 | Viral blood commensal |

| Papillomavirus | 1–12 | 5 | Viral skin commensal |

| Merkel cell polyomavirus | 1 | 3 | Unclear clinical significance; suspected lab contaminantb |

| WU polyomavirus | 3 | 1 | Unclear clinical significance; suspected lab contaminantb |

| Rotavirus | 1–4 | 5 | Suspected lab contaminantb |

| Enterovirus D68 | 1–3 | 2 | Suspected lab contaminant (Greninger et al. [8])b |

| Molluscum contagiosum virus | 1 | 1 | Suspected lab contaminantb |

Viruses with nonhuman hosts (e.g., insect viruses, phages, mouse gammaretroviruses) are not reported.

Detected in other unrelated sequencing data sets processed in the research laboratory at the same time.

Clinical presentation of patients with CHIKV/ZIKV coinfection.

The first patient of two patients found to be coinfected with ZIKV and CHIKV (Bahia08) was a 48-year-old woman from Salvador, Brazil, seen in the hospital emergency room (ER) on 15 July 2015 with 2 days of joint pain involving the elbows, hands, knees, and ankles associated with fever, myalgia, nausea, and headache. She also complained of dysuria but denied rash or conjunctivitis. Vital signs in the ER revealed a low-grade fever (37.9°C), and physical exam showed diffuse joint pain that made it difficult for her to lift her arms or grasp objects with her hands. Laboratory tests were remarkable only for leukopenia (white blood cell [WBC] count of 1,900 cells/μl [normal range, 4,500 to 10,000]) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count of 124,000 cells/μl; [normal range, 150,000 to 400,000]) (hemoglobin, 13.4 g/dl [normal range, 12.0 to 15.5 g/dl]). Dengue IgG, IgM, and NS1 serologies were unreactive. A urinalysis showed 36,500 red blood cells (RBCs) and 11,500 WBCs per ml; leukocyte esterase was negative, as was urine culture. The patient was treated with pain medications and discharged home. She returned to the ER 15 and 21 days after the initial visit with persistent neck pain and arthralgias and was discharged from the ER both times with pain medications.

The second patient (Bahia09) was a 40-year-old woman presenting 15 April 2015 with a 2-day history of fever, conjunctivitis, myalgia, and pruritic rash. Exam revealed a diffuse rash, conjunctival hyperemia, and a painful posterior cervical lymph node measuring 5 mm. Vital signs were normal. Laboratory tests were remarkable for mild leukopenia (WBC count of 3,930 cells/μl, with 39% neutrophils and 43% lymphocytes); hemoglobin and platelet counts were normal at 13.0 g/liter and 227,000 cells/μl, respectively. Dengue serologies were negative. The patient fully recovered 7 days after symptom onset.

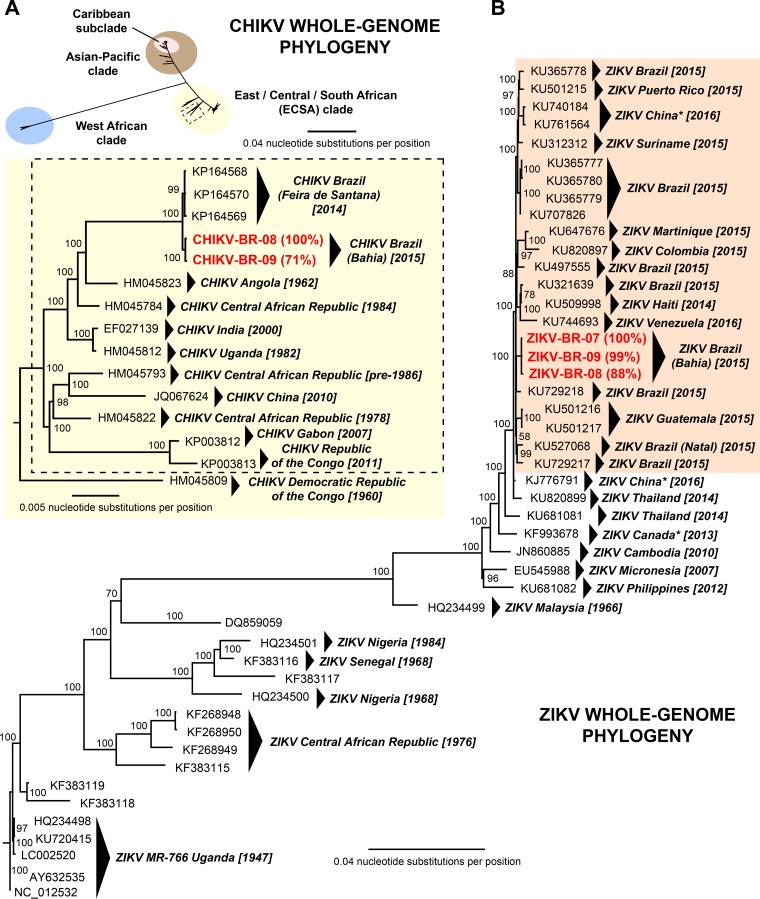

Genome assembly and phylogenetic analysis of ZIKV and CHIKV.

We assembled 100% and 71% of the CHIKV genome corresponding to the two coinfected patients with samples Bahia08 and Bahia09, respectively, by mapping the CHIKV mNGS reads to the most closely matched reference genome in NCBI GenBank identified using SURPI. Similarly, 99% of the ZIKV genome from sample Bahia09 and 100% of the ZIKV genome from the third ZIKV patient who was not coinfected (Bahia07) were assembled directly from mNGS reads. To recover 88% of the ZIKV Bahia08 genome, we boosted the number of mNGS reads using ZIKV capture probe enrichment of the metagenomic libraries (14). Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, including all of the 43 publicly available ZIKV genomes in the NCBI GenBank database as of March 2016, positioned the three newly sequenced ZIKV genomes in a Brazilian subclade corresponding to all of the sequenced strains to date from the ongoing 2015-2016 ZIKV outbreak (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the two CHIKV genomes were placed within a previously described Brazilian subclade (16) that is an offshoot of the East/Central/South African lineage (2) (Fig. 2A). The three ZIKV genomes from Bahia, Brazil, as well as the two CHIKV genomes, grouped together into local clusters by phylogenetic analysis.

FIG 2.

Whole-genome phylogeny of CHIKV and ZIKV. (A, upper portion) Phylogeny of all 314 CHIKV genomes available in NCBI GenBank as of March 2016 and 2 new complete or partial genomes from the current study. The three major lineages of CHIKV are shown in different colors. (A, lower portion) Phylogeny of 14 genomes corresponding to a local cluster within the ECSA (East/Central/South African) clade outlined with a dashed box in the upper portion. An ECSA CHIKV isolate located outside the cluster, HM045809, is included as an outgroup. (B) Phylogeny of all 44 ZIKV genomes available in NCBI GenBank as of March 2016 and 3 new complete or partial genomes from the current study. Genomes corresponding to the 2015-2016 ZIKV outbreak in Latin America are highlighted with a light orange background. The asterisks denote genomes corresponding to ZIKV cases in returning travelers. New CHIKV and ZIKV genomes sequenced in the current study are highlighted in boldface red, with the percent genome recovery provided in parentheses. Branch lengths are drawn proportionally to the number of nucleotide substitutions per position, and support values are shown for each node.

DISCUSSION

We report mosquito-borne ZIKV/CHIKV coinfections in 2 of 15 (13.3%) acutely symptomatic individuals with established ZIKV infection in Bahia state, Brazil. These data suggest that the incidence of arboviral coinfections in an ongoing ZIKV outbreak setting (1) may be higher than previously thought. There have been only three cases of ZIKV coinfections described thus far, two patients with ZIKV and DENV coinfection in New Caledonia (17) and one patient with ZIKV, CHIKV, and DENV coinfection from Colombia (18). Similar to these prior reports, the coinfections in the current study did not appear to result in more severe or fulminant disease requiring hospitalization. However, it is notable that infection by the virus present at a higher titer was reflected in the clinical presentation of the two coinfected patients. The first patient (strain Bahia08), with a high serum titer of CHIKV, presented with a prolonged “CHIKV-like” illness characterized by urinary inflammation (19) and prominent arthralgias (2) that persisted for weeks, resulting in repeated ER visits, whereas the second patient (strain Bahia09), with a higher titer of ZIKV, presented with a classic “ZIKV-like” presentation consisting of fever, rash, myalgia, and conjunctivitis (1).

An emerging diagnostic approach, mNGS, enables detection of all potential pathogens in clinical samples on the basis of uniquely identifying sequence information (9, 10). As the number of viral reads appears to be positively correlated with viral titer (Fig. 1), quantitative or at least semiquantitative information can potentially be extracted from mNGS data. In addition, the genetic information obtained by sequencing is useful for tracking of viral evolution (20), monitoring the geographic and temporal spread of the outbreak (21), and discovery of new viral lineages circulating in the region (14). As a surveillance tool, mNGS also has the potential to elucidate the spectrum of infection in a local geographic area, and thus guide the development of targeted diagnostics, antimicrobial drugs, and vaccines. Traditionally, barriers to NGS implementation have included high costs, complex instrumentation, and lack of dedicated bioinformatic tools. These barriers are being overcome with the development of rapid computational pipelines for analysis of mNGS data (9, 22, 23), as well as emergence of portable sequencers that can be used in field laboratories and other point-of-care settings (24, 25). The establishment of robust cutoff thresholds for determining positive results will also be needed before mNGS can be used routinely for infectious disease diagnosis. In particular, our results show that the concordance between PCR and mNGS, or between different PCR assays at borderline titers near the limits of detection, while very good, is not perfect (Table 1). Specifically, mNGS was likely more sensitive for detection of CHIKV than the CHIKV PCR used in the current study, given that 8.6% and 9.8% of the viral genome was recovered by mNGS from two CHIKV-negative samples (negative by PCR), while mNGS was less sensitive or as sensitive as the ZIKV PCR assays (Table 1). Such discrepancies between mNGS and PCR at very low viral titers have been previously reported in the other metagenomic studies (26, 27) and can potentially be addressed by formal clinical validation of mNGS assay performance and the use of rigorous negative and positive controls (28).

It is now established that ZIKV is the cause of severe fetal complications in pregnancy such as in utero demise and microcephaly (4). In addition, current cocirculation of all three mosquito-borne arboviruses in Latin America makes diagnosis based solely on clinical or epidemiological criteria unreliable. In our study, CHIKV coinfection was detected incidentally by mNGS of ZIKV-infected patients, underscoring the potential utility of unbiased mNGS sequencing for differential diagnosis of vector-borne febrile illness and identification of coinfections. The failure to detect other pathogens, such as malaria, by comprehensive mNGS suggests that a multiplex assay confined to arboviral infections (ZIKV, DENV, and CHIKV) may be sufficient for diagnosis and surveillance during the ongoing ZIKV outbreak (29).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank multiple researchers worldwide for permission to include their unpublished ZIKV genomes in our analysis.

This study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Abbott Laboratories.

C.Y.C. is the director of the UCSF-Abbott Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center and receives research support from Abbott Laboratories, Inc. The other authors disclose no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fauci AS, Morens DM. 2016. Zika virus in the Americas–yet another arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med 374:601–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver SC, Lecuit M. 2015. Chikungunya virus and the global spread of a mosquito-borne disease. N Engl J Med 372:1231–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1406035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carod-Artal FJ, Wichmann O, Farrar J, Gascon J. 2013. Neurological complications of dengue virus infection. Lancet Neurol 12:906–919. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. 2016. Zika virus and birth defects — reviewing the evidence for causality. N Engl J Med 374:1981–1987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastere S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, Dub T, Baudouin L, Teissier A, Larre P, Vial AL, Decam C, Choumet V, Halstead SK, Willison HJ, Musset L, Manuguerra JC, Despres P, Fournier E, Mallet HP, Musso D, Fontanet A, Neil J, Ghawche F. 2016. Guillain-Barre syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet 387:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balm MN, Lee CK, Lee HK, Chiu L, Koay ES, Tang JW. 2012. A diagnostic polymerase chain reaction assay for Zika virus. J Med Virol 84:1501–1505. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greninger AL, Messacar K, Dunnebacke T, Naccache SN, Federman S, Bouquet J, Mirsky D, Nomura Y, Yagi S, Glaser C, Vollmer M, Press CA, Klenschmidt-DeMasters BK, Dominguez SR, Chiu CY. 2015. Clinical metagenomic identification of Balamuthia mandrillaris encephalitis and assembly of the draft genome: the continuing case for reference genome sequencing. Genome Med 7:113. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0235-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Messacar K, Clayton A, Yu G, Somasekar S, Federman S, Stryke D, Anderson C, Yagi S, Messenger S, Wadford D, Xia D, Watt JP, Van Haren K, Dominguez SR, Glaser C, Aldrovandi G, Chiu CY. 2015. A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA (2012-14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:671–682. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naccache SN, Federman S, Veeraraghavan N, Zaharia M, Lee D, Samayoa E, Bouquet J, Greninger AL, Luk KC, Enge B, Wadford DA, Messenger SL, Genrich GL, Pellegrino K, Grard G, Leroy E, Schneider BS, Fair JN, Martinez MA, Isa P, Crump JA, DeRisi JL, Sittler T, Hackett J Jr, Miller S, Chiu CY. 2014. A cloud-compatible bioinformatics pipeline for ultrarapid pathogen identification from next-generation sequencing of clinical samples. Genome Res 24:1180–1192. doi: 10.1101/gr.171934.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu CY, Bres V, Yu G, Krysztof D, Naccache SN, Lee D, Pfeil J, Linnen JM, Stramer SL. 2015. Genomic assays for identification of chikungunya virus in blood donors, Puerto Rico, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1409–1413. doi: 10.3201/eid2108.150458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeffer M, Linssen B, Parke MD, Kinney RM. 2002. Specific detection of chikungunya virus using a RT-PCR/nested PCR combination. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 49:49–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, Johnson AJ, Stanfield SM, Duffy MR. 2008. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis 14:1232–1239. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lanciotti RS, Calisher CH, Gubler DJ, Chang GJ, Vorndam AV. 1992. Rapid detection and typing of dengue viruses from clinical samples by using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol 30:545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naccache SN, Thézé J, Sardi SI, Somasekar S, Greninger AL, Bandeira AC, Campos GS, Tauro LB, Faria NR, Pybus OG, Chiu CY. 2016. Distinct Zika virus lineage in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis doi: 10.3201/eid2210.160663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campos GS, Bandeira AC, Sardi SI. 2015. Zika virus outbreak, Bahia, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1885–1886. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nunes MR, Faria NR, de Vasconcelos JM, Golding N, Kraemer MU, de Oliveira LF, Azevedo RDS, da Silva DE, da Silva EV, da Silva SP, Carvalho VL, Coelho GE, Cruz AC, Rodrigues SG, Vianez JL Jr, Nunes BT, Cardoso JF, Tesh RB, Hay SI, Pybus OG, Vasconcelos PF. 2015. Emergence and potential for spread of Chikungunya virus in Brazil. BMC Med 13:102. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, O'Connor O, Calvez E, Daures M, John M, Grangeon JP, Gourinat AC. 2015. Co-infection with Zika and dengue viruses in 2 patients, New Caledonia, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis 21:381–382. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villamil-Gomez WE, Gonzalez-Camargo O, Rodriguez-Ayubi J, Zapata-Serpa D, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. 3 January 2016. Dengue, chikungunya and Zika co-infection in a patient from Colombia. J Infect Public Health doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baishya R, Jain V, Ganpule A, Muthu V, Sabnis RB, Desai MR. 2010. Urological manifestations of Chikungunya fever: a single centre experience. Urol Ann 2:110–113. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.68859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gire SK, Goba A, Andersen KG, Sealfon RS, Park DJ, Kanneh L, Jalloh S, Momoh M, Fullah M, Dudas G, Wohl S, Moses LM, Yozwiak NL, Winnicki S, Matranga CB, Malboeuf CM, Qu J, Gladden AD, Schaffner SF, Yang X, Jiang PP, Nekoui M, Colubri A, Coomber MR, Fonnie M, Moigboi A, Gbakie M, Kamara FK, Tucker V, Konuwa E, Saffa S, Sellu J, Jalloh AA, Kovoma A, Koninga J, Mustapha I, Kargbo K, Foday M, Yillah M, Kanneh F, Robert W, Massally JL, Chapman SB, Bochicchio J, Murphy C, Nusbaum C, Young S, Birren BW, Grant DS, Scheiffelin JS, Lander ES, Happi C, et al.. 2014. Genomic surveillance elucidates Ebola virus origin and transmission during the 2014 outbreak. Science 345:1369–1372. doi: 10.1126/science.1259657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faria NR, Azevedo RDS, Kraemer MU, Souza R, Cunha MS, Hill SC, Theze J, Bonsall MB, Bowden TA, Rissanen I, Rocco IM, Nogueira JS, Maeda AY, Vasami FG, Macedo FL, Suzuki A, Rodrigues SG, Cruz AC, Nunes BT, Medeiros DB, Rodrigues DS, Nunes Queiroz AL, da Silva EV, Henriques DF, Travassos da Rosa ES, de Oliveira CS, Martins LC, Vasconcelos HB, Casseb LM, Simith DDB, Messina JP, Abade L, Lourenco J, Alcantara LC, de Lima MM, Giovanetti M, Hay SI, de Oliveira RS, Lemos PDS, de Oliveira LF, de Lima CP, da Silva SP, de Vasconcelos JM, Franco L, Cardoso JF, Vianez-Junior JL, Mir D, Bello G, Delatorre E, Khan K, et al.. 2016. Zika virus in the Americas: early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science 352:345–349. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flygare S, Simmon K, Miller C, Qiao Y, Kennedy B, Di Sera T, Graf EH, Tardif KD, Kapusta A, Rynearson S, Stockmann C, Queen K, Tong S, Voelkerding KV, Blaschke A, Byington CL, Jain S, Pavia A, Ampofo K, Eilbeck K, Marth G, Yandell M, Schlaberg R. 2016. Taxonomer: an interactive metagenomics analysis portal for universal pathogen detection and host mRNA expression profiling. Genome Biol 17:111. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood DE, Salzberg SL. 2014. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol 15:R46. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-3-r46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Federman S, Yu G, Mbala P, Bres V, Stryke D, Bouquet J, Somasekar S, Linnen JM, Dodd R, Mulembakani P, Schneider BS, Muyembe-Tamfum JJ, Stramer SL, Chiu CY. 2015. Rapid metagenomic identification of viral pathogens in clinical samples by real-time nanopore sequencing analysis. Genome Med 7:99. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quick J, Loman NJ, Duraffour S, Simpson JT, Severi E, Cowley L, Bore JA, Koundouno R, Dudas G, Mikhail A, Ouedraogo N, Afrough B, Bah A, Baum JH, Becker-Ziaja B, Boettcher JP, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Camino-Sanchez A, Carter LL, Doerrbecker J, Enkirch T, Garcia-Dorival I, Hetzelt N, Hinzmann J, Holm T, Kafetzopoulou LE, Koropogui M, Kosgey A, Kuisma E, Logue CH, Mazzarelli A, Meisel S, Mertens M, Michel J, Ngabo D, Nitzsche K, Pallasch E, Patrono LV, Portmann J, Repits JG, Rickett NY, Sachse A, Singethan K, Vitoriano I, Yemanaberhan RL, Zekeng EG, Racine T, Bello A, Sall AA, Faye O, Faye O, et al. 2016. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature 530:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature16996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheval J, Sauvage V, Frangeul L, Dacheux L, Guigon G, Dumey N, Pariente K, Rousseaux C, Dorange F, Berthet N, Brisse S, Moszer I, Bourhy H, Manuguerra CJ, Lecuit M, Burguiere A, Caro V, Eloit M. 2011. Evaluation of high-throughput sequencing for identifying known and unknown viruses in biological samples. J Clin Microbiol 49:3268–3275. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00850-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wylie TN, Wylie KM, Herter BN, Storch GA. 2015. Enhanced virome sequencing using targeted sequence capture. Genome Res 25:1910–1920. doi: 10.1101/gr.191049.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg B, Sichtig H, Geyer C, Ledeboer N, Weinstock GM. 2015. Making the leap from research laboratory to clinic: challenges and opportunities for next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnostics. mBio 6:e01888-15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01888-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 February 2016. Revised diagnostic testing for Zika, chikungunya, and dengue viruses in US Public Health Laboratories. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/denvchikvzikv-testing-algorithm.pdf. [Google Scholar]