Abstract

Amphibian populations are experiencing catastrophic declines driven by the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). Although horizontal gene transfer (HGT) facilitates the evolution and adaptation in many fungi by conferring novel function genes to the recipient fungi, inter-kingdom HGT in Bd remains largely unexplored. In this study, our investigation detects 19 bacterial genes transferred to Bd, including metallo-beta-lactamase and arsenate reductase that play important roles in the resistance to antibiotics and arsenates. Moreover, three probable HGT gene families in Bd are from plants and one gene family coding the ankyrin repeat-containing protein appears to come from oomycetes. The observed multi-copy gene families associated with HGT are probably due to the independent transfer events or gene duplications. Five HGT genes with extracellular locations may relate to infection, and some other genes may participate in a variety of metabolic pathways, and in doing so add important metabolic traits to the recipient. The evolutionary analysis indicates that all the transferred genes evolved under purifying selection, suggesting that their functions in Bd are similar to those of the donors. Collectively, our results indicate that HGT from diverse donors may be an important evolutionary driver of Bd, and improve its adaptations for infecting and colonizing host amphibians.

Keywords: horizontal gene transfer, fungal pathogen, amphibian, evolutionary analysis, purifying selection

Introduction

Globally, amphibian populations are facing massive declines due to many factors. One insidious driver of the catastrophic die-offs is the emerging global pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which is a chytrid fungus (Longcore et al., 1999; Hof et al., 2011). This fungus, which causes chytridiomycosis, occurs in hundreds of amphibian species (Berger et al., 1998), (Skerratt et al., 2007; Wake and Vredenburg, 2008). Most studies on Bd have focused mainly on its ecology and population genetics. The molecular mechanism of its infection and lethality remains largely unexplored (Morehouse et al., 2003; Morgan et al., 2007). The evolutionary position of the poorly characterized Chytridiomycota presents a major challenge to understanding this fungal species. Chytrids are basal fungi separated by a vast evolutionary distance from any well-characterized relatives (James et al., 2006; Rosenblum et al., 2008). Fortunately, the Joint Genome Institute and Broad Institute sequenced complete genomes of the Bd strains JAM81 and JEL423, respectively. These genomes data facilitate genomic investigations of molecular mechanisms of their infection lifestyle.

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) involves the transmission of genetic material across species boundaries. It is an important evolutionary driver of the genomes of many organisms because one organism can acquire novel functional genes rapidly from another organism. Such newly acquired genes accelerate the adaptation and evolution of the recipients (Mitreva et al., 2009; Richards et al., 2011b). Horizontal gene transfer has been extensively studied and its significance in prokaryotic evolution is well known (Doolittle, 2005; Boucher et al., 2007; Dagan et al., 2008; Dorman and Kane, 2009). HGT also contributes significantly to evolution of fungi and other eukaryotes, although knowledge about HGT in eukaryotes is limited (Keeling and Palmer, 2008). A variety of cases are known among fungi (Richards et al., 2011a), including single-gene (Strope et al., 2011), gene clusters (Khaldi et al., 2008; Slot and Rokas, 2010, 2011; Campbell et al., 2012) and entire chromosomal transfers (Rosewich and Kistler, 2000; Ma et al., 2010; van der Does and Rep, 2012). Fungi also can acquire functional genes from organisms in other kingdoms such as bacteria, viruses, plants, and animals (Rosewich and Kistler, 2000; Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón, 2010; Fitzpatrick, 2011; Richards et al., 2011a). Horizontal gene transfer can yield instant advantages to fungal metabolism, propagation and pathogenicity and in doing so bestow significant selective advantages (Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón, 2010; Fitzpatrick, 2011; Richards et al., 2011a). Among the inter-kingdom HGT cases, fungi most frequently acquire novel genes from bacteria. Though exceedingly rare, fungi also can acquire genes from plants and animals (Richards et al., 2009; Selman et al., 2011; Pombert et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2014).

A recent HGT study on Bd revealed that two large families of known virulence-effector genes, crinkler (CRN) proteins and serine peptidases, were acquired by Bd from oomycete pathogens and bacteria, respectively (Sun et al., 2011). These two gene families have duplicated and evolved under strong positive selection, which may relate to the virulence of Bd to its amphibian hosts. It is probable that Bd acquired other important functional genes via HGT, facilitating its adaptation of pathogenic lifestyle. To address this possibility, we focused on inter-kingdom HGT by analyzing protein sets of the two Bd strains and exploring gene transfer from suites of non-fungi species ranging from viruses, bacteria, protists, plants and animals. We use comprehensive homology searching and phylogenetic analyses to detect all probable HGT candidates and then analyze their functional and evolutionary contributions to Bd. We discovered that many bacteria-derived genes exist in Bd in addition to serine peptidases, three transferred genes appear to have botanical origins and the gene family coding the ankyrin repeat-containing protein may originate from oomycetes. No credible evidence indicates HGT from host amphibians. Some functional genes involve multiple transfers yet others duplicated subsequent to their HGT. Functional analyses indicate horizontally transferred genes appear to play important physiological roles in Bd. Overall, HGT from diverse donors may be an important evolutionary driver of Bd.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We retrieved 8700 and 8818 predicted proteins of Bd JAM81 and JEL423 from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein) and the Broad Institute (http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/batrachochytrium_dendrobatidis/MultiDownloads.html), respectively. Further, we downloaded protein sequences in the RefSeq of NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/release/) for a wide diversity of bacteria, fungi, protozoans, viruses, plants, and animals. We constructed two local proteome databases for the RefSeq sequences. One database contained all proteins of fungi with completed genomes in RefSeq and the other one was comprised of all the proteomes excluding fungi. The whole-genome expression assays data of Bd JAM81 with GEO accession number GSE37135 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE37135) were downloaded to quantify expression levels of horizontally transferred genes (Rosenblum et al., 2012).

Screening for HGT candidates

A multi-step bioinformatic pipeline was used to identify candidate HGTs (Figure 1 and Table S1). Blast (Altschul et al., 1997) was employed to screen proteins present in only a few fungal species but widespread in other groups. First, each protein sequence occurring in both Bd strains was compared with fungal sequences in the local database using BLASTP. Blast results were filtered based on an e-value threshold of 1e−10 and a continuous overlap threshold of 33% with the query protein. Proteins with homologs in five or fewer fungi were selected as possible HGTs involving Bd only as well as ancient HGTs (Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón, 2010). These candidates were then compared to the non-fungi database via BLASTP with the same e-value threshold. Next, we constructed the phylogeny of each protein with homologs in more than 20 non-fungal species to validate the HGT (see below).

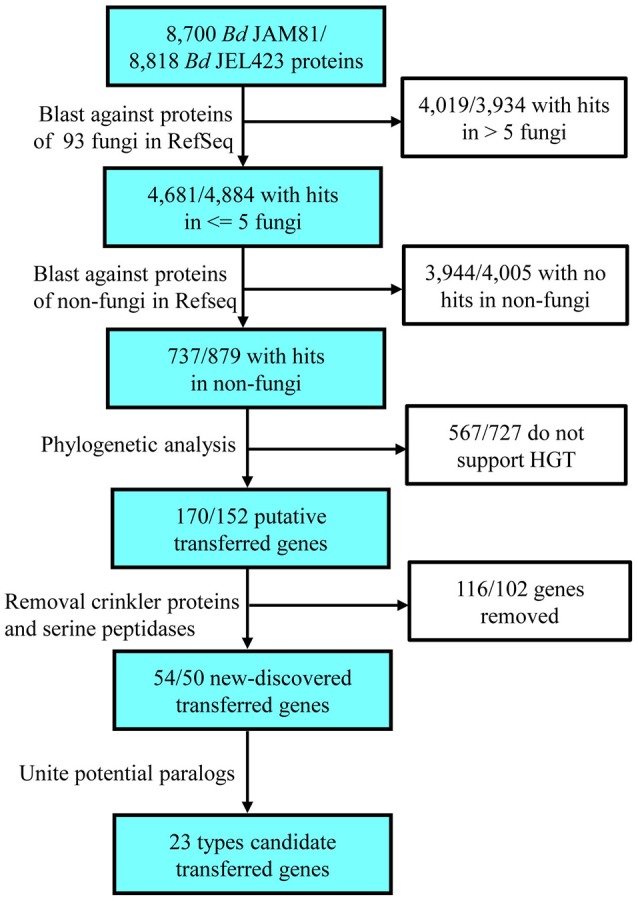

Figure 1.

Flowchart used to search for horizontally transferred genes in Bd and the results of each step. In total, 23 types of transferred genes were detected in Bd.

To exclude possible DNA contaminates, the two Bd strains were assumed to be independently evolving entities and, therefore, unlikely to host identical contaminates. Accordingly, we retained candidate genes present in both strains. Gene phylogenies were generated to detect the origins of candidates. Vertical inheritance was assumed to be generally congruent with the species' phylogeny such that a putative HGT gene was physically linked to native genes on the genome of Bd (Sun et al., 2011). Further, because bacteria lack introns, we retrieved the number of exons in potentially horizontally transferred genes from gff files of the genome sequences.

Phylogenetic analyses

Homologs of horizontally transferred genes were searched in non-redundant databases by BLASTP (e = 1e−10). Next, homologous protein sets were submitted to multiple alignments using ClustalW2 (Thompson et al., 1994). Subsequently, the alignments were inspected visually and refined manually. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML). We also constructed distance-based neighbor-joining (NJ) trees.

Bayesian trees were generated by MrBayes 3.1.2 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). Each candidate HGT was submitted to two independent analyses using four MCMC chains based on models of amino acid substitution estimated by Prottest 3.0 (Abascal et al., 2005). We ran analyses for one million generations with a sampling frequency of 100 generations. Analyses were stopped when the average deviation of split frequencies was less than 0.01. The initial 25% of the total trees was discarded as burn-in. Compatible groups were shown in the majority rule consensus tree. Maximum likelihood trees were constructed using Phyml 3.1 (Guindon et al., 2010) with the best-fit evolutionary model suggested by Prottest 3.0 (Abascal et al., 2005). Branch support values were gained by performing 1000 bootstraps. NJ trees were constructed using Neighbor in MEGA6 (Tamura et al., 2013). Bootstrap values were obtained by generating 1000 pseudoreplicates. HGT was inferred when the topology within a well-supported clade contained non-sister species. Direction of transfer was inferred from the distribution of the horizontally transferred gene and its placement on the trees.

Evolutionary mapping of HGTs

Two scenarios could explain the presence of homologs for some horizontally transferred genes: multiple transfer events from different donors and gene duplication subsequent to a transfer. Homology searches and phylogenetic analyses were used to infer the best scenario. If paralogs had top BLAST hits to the same or a sister organism then these genes were assumed to be generated by one HGT event followed by duplication. Alternatively, paralogs from multiple transfer events had different putative donors located in different clades of the trees. In addition, these proteins were used to TBLASTN against the whole genome of Bd (e = 10−10) to identify potential pseudogenes, those that could not translate.

Putative functional assignment

We performed COG, GO, and KEGG analyses for each horizontally transferred gene to infer its function. The KEGG analyses mainly investigated if proteins from HGT participated in metabolic networks of Bds. We used KAAS (Kegg automated annotation server) to project the transferred genes onto Kegg's collection of metabolic pathways (Moriya et al., 2007) by BDH (bidirectional hit) orthology searching.

All HGT proteins were subjected to SignalP (Bendtsen et al., 2004), TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2007), and TMHMM (Sonnhammer et al., 1998) analyses to identify and predict their secreted proteins and to look for possible secretion signals and/or transmembrane domains. We also used WoLFPSORT (Horton et al., 2007) to investigate their putative cellular locations.

Selection analyses

Selection pressure analyses were conducted for each HGT gene. We estimated the ML computation of non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates, and their ratio Ka/Ks omega values for horizontally transferred genes in Bd and their homologs in corresponding donors. Codeml in the PAML 4 package was used to calculate the Ka/Ks values (Yang, 2007).

Results

Twenty-three gene families in two Bd strains via HGT

Stringent filters were employed to identify promising HGT genes in the annotated protein sequences of Bd JAM81 and Bd JEL423. Searches for protein-coding genes not broadly shared with other fungi yielded 4681 and 4884 homologs for Bd JAM81 and JEL423, respectively. No more than five fungal taxa shared these genes with Bd. Among these proteins, 737 and 879, respectively, were highly similar to those of non-fungi and, thus, they were considered to be candidate HGT genes. In addition to serine peptidases and CRN (Sun et al., 2011), phylogenetic analyses identified 54 and 50 proteins belonging to 23 families in Bd JAM81 and Bd JEL423, respectively, as being potentially obtained by HGT (Figure 1). All 23 of these families were validated by BI, ML phylogenies, as well as NJ trees, and with Bayesian posterior probabilities >90% and bootstrap support values of ML and NJ greater than 80% (Table 1, Figure 2, and Figure S1). The expressed data (Rosenblum et al., 2012) indicated all these candidate HGT genes were with expression, suggesting they were functional.

Table 1.

The 23 types of candidate HGT genes in Bd genome.

| No. | Putative gene product | Putative donor | E-value | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phosphate-responsive 1 family protein | Plant | 8E-34 | 36 |

| 2 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | Plant | 5E-101 | 46 |

| 3 | aarF domain-containing protein kinase | Plant | 7E-33 | 33 |

| 4 | Metallo-beta-lactamase | Bacteria | 3E-38 | 39 |

| 5 | Adenylate cyclase | Bacteria | 3E-95 | 36 |

| 6 | Carbonic anhydrase | Bacteria | 2E-81 | 57 |

| 7 | Chitinase | Bacteria | 3E-99 | 50 |

| 8 | Sel1 repeat-containing protein | Bacteria | 3E-110 | 45 |

| 9 | Secreted glycoside hydrolase | Bacteria | 3E-80 | 42 |

| 10 | 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase | Bacteria | 2E-80 | 49 |

| 11 | Arsenate reductase | Bacteria | 1E-53 | 66 |

| 12 | Membrane protein | Bacteria | 3E-36 | 42 |

| 13 | Alpha/Beta hydrolase | Bacteria | 3E-55 | 33 |

| 14 | Carboxylate-amine ligase | Bacteria | 2E-35 | 33 |

| 15 | Glutathione peroxidase | Bacteria | 2E-71 | 63 |

| 16 | Glutathione synthetase | Bacteria | 7E-42 | 37 |

| 17 | Aminopeptidase | Bacteria | 7E-167 | 38 |

| 18 | Glutamine synthetase | Bacteria | 0 | 51 |

| 19 | Succinylglutamate desuccinylase | Bacteria | 1E-100 | 48 |

| 20 | D-alanine–D-alanine ligase | Bacteria | 8E-167 | 39 |

| 21 | Glutamyl-tRNA amidotransferase | Bacteria | 6E-15 | 48 |

| 22 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | Bacteria | 6E-29 | 57 |

| 23 | Ankyrin repeat-containing protein | Oomycete | 5E-113 | 51 |

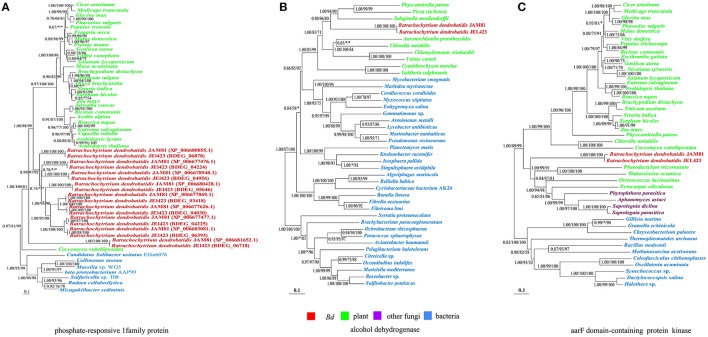

Figure 2.

Phylogenies of genes encoding (from left to right) phosphate-responsive 1 family protein, alcohol dehydrogenase and aarF domain-containing protein kinase horizontally transferred from plants to Bd. The Bayesian inference tree is shown unrooted. The Bayesian tree is virtually identical to ML and NJ trees. Numbers at nodes represent bayesian posterior probabilities (A) and bootstrap values of maximum likelihood (B) and neighbor-joining (C) respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate support values < 50. The scale bar corresponds to the estimated number of amino acid substitutions per site.

The putative donors of transferred genes included prokaryotes, plants and oomycetes. Bd appeared to have derived three gene families that code for phosphate-responsive 1 family protein (Figure 2A), alcohol dehydrogenase (Figure 2B) and aarF domain-containing protein kinase from plants (Figure 2C). Their expression indicated that they are functional and not pseudogenes. In especial, to phosphate-responsive 1 family protein (Figure 2A), most plant species own this gene, indicating it is widely present in plant, while only a few fungi have this gene, so it is more possible that this gene in Bd is transferred from plant; while this gene in coccomyxa may be transferred from Bd or other fungi species. HGT events from plants to fungi were rare and only a few of these transfer events have been reported. Considering the sparse occurrence, these three gene families derived from plants may endow the recipient Bd with novel important traits and have important role in evolution and adaptation of Bd. Other 19 gene families were acquired from various bacteria. The aquatic habitat of some bacterial donors may have facilitated the transfer of genetic material from them to Bd. In addition, Bd also obtained one ankyrin repeat-containing protein family from oomycete pathogens. This gene subsequently duplicated in Bd. All these acquired genes have no endogenous homologs in Bd, indicating that they offer novel functions to Bd.

We also explored possible HGT between Bd and their amphibian hosts but without success. Several protein sequences of Bd that were missing from other fungi had high similarity with their amphibian hosts. However, phylogenetic analyses did not support the hypothesis of HGT from amphibians to Bd.

Several lines of evidence eliminate the possibility of contamination from bacteria, oomycetes or plants, which could explain our results. First, all transferred genes occur in both Bd strains, rendering contamination unlikely (Richards et al., 2011b). Second, contigs having the horizontally transferred genes contain more than five genes total, thus assuring quality of the assemblies and further precluding contamination. In addition, all flanking DNA sequences of the transferred genes show substantial similarity to fungal sequences. Fungal sequences of vertical inheritance surround the putatively transferred genes. Thus, native fungal sequences link to horizontally transferred genes (Richards et al., 2011b). Finally, most of transferred genes contain introns (Table S2), which further precludes bacterial contaminates.

Multi-copies of 10 horizontally transferred gene families in Bd

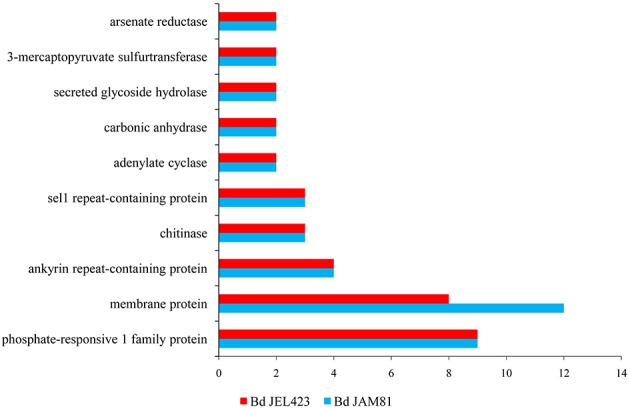

Both serine peptidases and CRN proteins were indicated to be highly duplicated in Bd (Sun et al., 2011). Among our 23 newly discovered horizontally transferred gene families, phosphate-responsive 1 family protein, membrane protein, ankyrin repeat-containing protein, chitinase, sel1 repeat-containing protein, adenylate cyclase, carbonate dehydratase, secreted glycoside hydrolase, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase, and arsenate reductase harbored a diverse number of copies (Figure 3). On the one hand, adenylate cyclase and carbonic anhydrase appeared to have undergone multiple HGT events for their copies located in different branches near potential donor species (Figure S1). On the other hand, some gene families diversified via duplication subsequent to a single HGT event, for their copies cluster together as the sister-clade to the donors (Figure S1), which indicated duplications (Nikoh et al., 2010). For example, both Bd strains had nine copies of the gene family encoding the phosphate-responsive 1 family protein, all of which constituted the sister-clade of plant homologs (Figure 2A). A similar evolutionary scenario occurred for the gene families encoding membrane proteins, all of the gene copies clustered with bacterial sequences (Figure S1).

Figure 3.

The copy number of horizontally transferred genes with paralogs in the two strains of Bd.

Diverse metabolic functions of transferred genes

The putative function and the biochemical pathways of the HGT candidates were deduced with COG, GO, and KEGG and are summarized in Table 2. COG categories indicated that these genes were mainly involved in energy production and conversion, signal transduction mechanisms, carbohydrate, amino acid, and inorganic ion transport and metabolism. In addition, some genes related functionally to cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, posttranslational modification, protein turnover and chaperones. GO analysis indicated that their functions related to a variety of activities, such as catalytic, hydrolase, transferase, cyclase, ligase, lyase, and oxidoreductase activities. Furthermore, some genes associated with antioxidant, peroxidase, arsenate reductase, responses to hypoxia, mechanical stimulus and growth. Most transferred genes had multiple functions and some functions appeared to benefit Bd considerably. These gene functions associated importantly with its niche adaptation. Functions such as antioxidant, peroxidase, and arsenate reductase activities likely related to its stress responses. In the KEGG databases, most genes appeared to be involved in sugar, carbohydrate, amino acid biosynthesis, and metabolism. Some genes participated in aspartate, glutamate, glutathione, arachidonic acid, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate, nitrogen and purine metabolism, which are critical for its life. Several independently transferred gene families participated in the same metabolic pathways, such as glutathione peroxidase, glutathione synthetase, and aminopeptidase, all of which related to glutathione metabolism. Overall, function analyses indicated these transferred genes endowed abundant novel functions to Bd.

Table 2.

The COG, GO, and KEGG biochemical pathway mappings and the predicted cellular locations of HGT genes.

| No. | Gene name | COG categories | GO categories | KEGG pathways | TargetP | SignalP | WoLF PSORT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Phosphate-responsive 1 family protein | Unknown | Microtubule nucleation | Unknown | S | YES | extr |

| 2 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | Energy production and conversion | Alcohol dehydrogenase activity | Metabolic pathways | – | cyto | |

| 3 | aarF domain-containing protein kinase | Unknown | ATP binding protein amino acid phosphorylation | Unknown | – | cyto | |

| 4 | Metallo-beta-lactamase | Predicted sugar phosphate isomerase | Beta-lactamase activity | Unknown | – | cyto | |

| 5 | Adenylate cyclase | Signal transduction mechanisms | Guanylate cyclase activity intracellular signaling cascade | Purine metabolism | M | mito | |

| Nucleotide metabolism | |||||||

| 6 | Carbonic anhydrase | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | Carbon utilization | Nitrogen metabolism | – | nucl | |

| 7 | Chitinase | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | Catalytic activity hydrolase activity | Carbohydrate metabolism | S | YES | extr |

| 8 | Sel1 repeat-containing protein | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis signal transduction mechanisms | Unknown | Unknown | M | cyto | |

| 9 | Secreted glycoside hydrolase | Unknown | Glucosylceramidase activity hydrolase activity | Carbohydrate metabolic process | S | extr | |

| 10 | 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | Catalytic activity transferase activity | Cysteine and methionine metabolism | M | cyto | |

| 11 | Arsenate reductase | Signal transduction mechanisms | Tyrosine phosphatase activity arsenate reductase activity | Unknown | – | cyto | |

| 12 | Membrane protein | Unknown | Integral to membrane | Unknown | – | plas | |

| 13 | Alpha/Beta hydrolase | Unknown | Hydrolase activity catalytic activity | Unknown | S | extr | |

| 14 | Carboxylate-amine ligase | Unknown | Catalytic activity ligase activity | Peptidoglycan biosynthetic process | – | cyto | |

| 15 | Glutathione peroxidase | Posttranslational modification protein turnover, chaperones | Response to oxidative stress antioxidant activity | Glutathione metabolism | – | cyto | |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | |||||||

| 16 | Glutathione synthetase | Unknown | Glutathione synthase activity glutathione biosynthetic process | Glutathione metabolism | – | cyto | |

| 17 | Aminopeptidase | Amino acid transport and metabolism | Proteolysis and peptidolysis aminopeptidase activity | Glutathione metabolism | – | cyto | |

| 18 | Glutamine synthetase | Amino acid transport and metabolism | Glutamate-ammonia ligase activity nitrogen fixation | Alanine, aspartate and Glutamate metabolism | M | mito | |

| 19 | Succinylglutamate desuccinylase | Unknown | Hydrolase activity catalytic activity | Unknown | – | cyto | |

| 20 | D-alanine–D-alanine ligase | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase activity | D-Alanine metabolism | – | cyto | |

| Peptidoglycan biosynthesis | |||||||

| 21 | Glutamyl-tRNA amidotransferase | Unknown | Carbon-nitrogen ligase activity | Unknown | M | mito | |

| 22 | Rhodanese-related sulfurtransferase | Unknown | Transferase activity | Sulfur relay system | – | cyto | |

| Sulfur metabolism | |||||||

| 23 | Ankyrin repeat-containing protein | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | S | extr |

The genes without definite information in the database were indicated with unknown. For genes participating in multiple function and biochemical pathways, all of them were shown. In the sixth column, S means secretory pathway, M refers to mitochondrion location and the minus means any other location. In the seventh column, YES means that the sequence has signal peptide. In the eighth column, extr, cyto, and mito show that the protein is likely localized in extracellular sites (highlighted in bold font), cytoplasm and mitochondria, respectively.

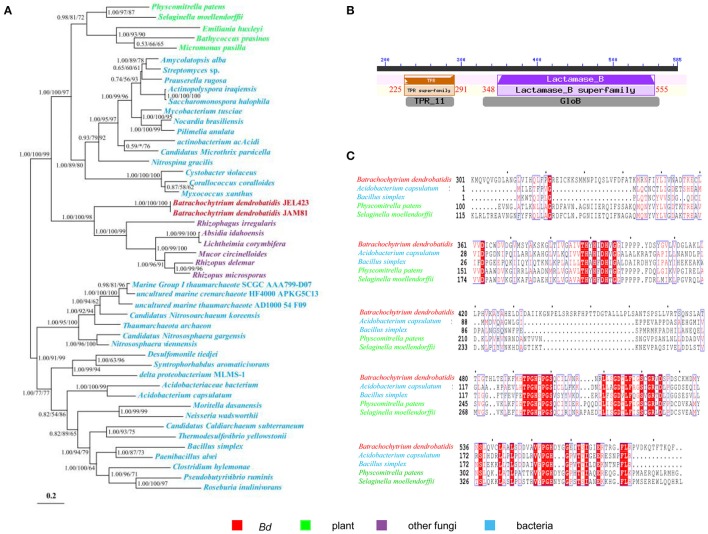

The acquisition of metallo-beta-lactamase and arsenate reductase from bacteria to Bd may have promoted defense. Metallo-beta-lactamases confer resistance to a broad range of antibiotics and inhibitors. Its HGT likely plays a major role in conquering new environments and hosts. The transfer of this gene from bacteria to fungi has been reported rarely. To Bd, its metallo-beta-lactamase well clusters within bacteria (Figure 4A) and contains conserved Lactamase_B domains as plant and bacteria (Figures 4B,C). Such transfers may play great roles in adaptation of Bd. The arsenate reductase is essential for arsenic detoxification and resistance by transforming arsenate into arsenite. Thus, the acquisition of a bacterial arsenate reductase by Bd might have endowed them with the ability to detoxify arsenics (Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón, 2010).

Figure 4.

The phylogeny and domain of the gene encoding metallo-beta-lactamase for Bd and other organisms. (A) Phylogeny showing HGT from bacteria to Bd. The Bayesian tree (shown) is virtually identical to ML and NJ trees. Nodal support values ≥50 shown (BI/ML/NJ). Asterisks (*) indicate support values < 50. Scale bar indicates substitutions per site. (B) Conserved domain of TRP (Tetratricopeptide repeat domain, Location: 225–291 nt) and Lactamase_B (Metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily, Location: 348–555 nt) in the gene of Bd encoding metallo-beta-lactamase. (C) Alignment of the gene of Bd encoding metallo-beta-lactamase and other organisms. Only the aligned regions are shown.

Putative cellular locations of HGTs

Five horizontally transferred gene families have presumed extracellular locations. These include phosphate-responsive 1 family protein, chitinase, secreted glycoside hydrolase, alpha/beta hydrolase and ankyrin repeat-containing protein (Table 2). Extracellular enzymes may relate to interactions between Bd and its hosts. Among these gene families, phosphate-responsive 1 family protein, which was probably derived from plant, relates to responses to hypoxia and mechanical stimulus as well as growth in plant. Its subsequent duplication in Bd implies important function(s). Chitinase, secreted glycoside hydrolase and alpha/beta hydrolase involve hydrolase activity, which may relate to the efficient infection of hosts by Bd. These enzymes have been reported to regulate the interactions between pathogenic bacteria and their hosts (Zhu et al., 2012), indicating an importance roles in adaptation of Bd. The bacterial origin and extracellular location of these enzymes in Bd suggests they may serve to break down chitin, which in amphibians serves to trigger an allergy/immune response (Tang et al., 2015). The duplication of genes encoding ankyrin repeat-containing protein (ANK) derived from oomycete indicates a great role played by this HGT gene family. ANK proteins were reported to represent a new family of bacterial type IV effectors that play a major role in host-pathogen interactions and the evolution of infections (Siozios et al., 2013). Thus, these proteins in Bd may also relate to host-pathogen interactions. Other HGT gene families that encode intracellular proteins play roles in various metabolic activities and their acquisitions relates to functional requirements of the recipients, highly utilization of carbohydrates and nutrition. Thus, the acquisition of multiple genes by HGT endows the recipient Bd with great advantages in its evolution and adaption.

Purifying selection of horizontally transferred genes

To assess selective pressure of these HGT genes, we computed the synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates, and the ratio Ka/Ks for all these HGT genes. Generally, Ka/Ks < 1 was assumed to indicate purifying selection, Ka/Ks = 1 indicated neutral evolution, and Ka/Ks > 1 indicated positive selection. Ka/Ks values for all transferred genes are less than 0.5, suggesting that they were undergone purifying selection. In general, Ka/Ks values relate to protein function and low values indicate that selective constraints has acted on functional genes, so the demonstration that selective constraints are operating on these genes supports the conclusion that these genes are fully functional in Bd (Wu and Zhang, 2011).

Discussion

In this study, we used a semi-automated pipeline to identify HGT candidates in Bd. The construction and analysis of phylogenetic trees is recognized as the most reliable method for detecting HGT, so we included several steps of manual phylogenetic trees inspection in the pipeline. Using this pipeline, we detected 3 gene families with evidences of HGT from plant, 19 HGTs from various bacteria and one from oomycete. HGT from plants to fungi is reported rarely. To data, only few evidences of these transfer events have been reported: UDP-glucosyltransferase in Botrytis cinerea was derived from Hieracium pilosella, one leucine-rich repeat protein in Pyrenophora was transferred from host barley and four additional plant-to-fungi HGTs are known (Richards et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2013). Here, we provided three well evidences of plant-fungi transfer events in Bd. In addition, it is well known that Bd is an amphibian parasitic fungi, HGT from plants to animal pathogenic fungi is fascinating. The aquatic environment provides an opportunity for Bd to obtain genes from aquatic plants. Among these three plant-derived gene families, alcohol dehydrogenase transferred between different bacteria and from bacteria to protists and fungi has been described (Field et al., 2000; Trcek and Matsushita, 2013). In contrast, its transfer from plants to fungi is rarely known. Functioning in protein kinase activity, aarF domain-containing protein kinase participates in protein amino acid phosphorylation. Further, phosphate-responsive 1 family protein duplicated subsequent to the HGT event. Their function annotations and evolution events indicated that these three plant-derived gene families may endow the recipient Bd with novel traits and enhance the adaptation of Bd to its hosts.

Bacteria and plants can donate genes to fungi via inter-kingdom HGT and so can animals. The gene encoding purine nucleotide phosphorylase (PNP) in Encephalitozoon romaleae was transferred from its insect host (Selman et al., 2011), as was the sterol carrier gene in Metarhizium robertsii and the latter transfer facilitated the pathogen's infection of insects (Zhao et al., 2014). In comparison, no evidence supports the transfer of genes from amphibian hosts to Bd. Nevertheless, we detected some proteins of Bd that were missing from other fungi had high similarity with their amphibian hosts, but the phylogenetic trees did not support the HGT hypothesis for they did not cluster with the amphibian hosts well. In our opinion, their high similarity with amphibian hosts may reflect molecular mimicry. This mechanism can allow fungal pathogens to mimic the proteins of their vertebrate hosts to evade the immune responses, such as occurs in parasitic nematodes (Shinya et al., 2013). Future functional experiments can further verify our speculation.

It is possible that the candidate HGT genes were in the common ancestor of donors and fungi but were lost subsequently in many fungi. However, this explanation is highly unlikely for three reasons. First, it requires massive independent losses to explain the presence of these genes only in Bd and a few other fungi only. Second, this hypothesis fails to explain the remarkable sequence identity between Bd and its candidate donors. Finally, loss fails to explain the clustering of HGT genes within bacteria, oomycetes or plants on well-supported nodes of the gene trees.

Duplications of some HGT genes further suggested their significance to Bd. The timing of HGT genes' duplications varies widely. Genes involved in membrane proteins appear to be recent duplications as indicated by the high levels of similarity among their copies, many of which show very little sequence variation. In contrast, the duplication of the phosphate-responsive 1 family protein exhibits a low level of similarity among its nine copies. These appear to be relatively ancient duplications. Most gene duplications events predate divergence of the two strains of Bd. Furthermore, neither Bd genome has pseudogenes among the 23 families. Gene duplication can contribute to the expansion of protein families (Danchin et al., 2010). The generation of new copies may relate to the specialized life and functional requirements of Bd.

Functional annotations and cellular locations indicate that the horizontally transferred genes not only participate in infection process, but also take part in various metabolic progresses. So, the acquisition of these genes contributes to evolution and adaption of Bd significantly. They can confer new capabilities to the recipient Bd: highly efficient infections of hosts and utilization of host carbohydrates and nutrition.

Moreover, it is meaningful that some HGT genes participate in same pathways. The acquisitions of multiple genes by HGT that participate in concert in same metabolic pathways have greater significance to the recipients than those that work alone. In fungi, glutathione plays key roles in their response to several stressful situations. Organisms mobilize glutathione under sulfur or nitrogen starvation to ensure cellular maintenance. Moreover, induction of the glutathione-dependent antioxidative defense system in response to carbon deprivation stress results in an increased tolerance to oxidative stress. This confers resistance against heat shock and osmotic stress, indicating that transfers of three genes participating in this pathway is important given Bd's aquatic lifestyle (Pócsi et al., 2004).

Conclusion

In summary, our results illustrate the scale of HGT and the roles it plays in the rapid evolution and adaptation of Bd. These horizontally transferred genes may be key adaptations that enhance colonization on amphibian hosts, perhaps leading to more effective spreading and competitive advantage. Meanwhile, these HGTs event may endow important evolutionary implications for Bb and its diseases in general. Future experiments will enable a better understanding of the functions and contributions of these HGTs to Bd.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: BS, TL, and DH. Analyzed the data: BS, TL, and JX. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: LL, PZ, and SH. Wrote the paper: BS, TL, RM, and DH.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant no. 31210103912, 31172072), partially by a grant (No. O529YX5105) from the Key Laboratory of the Zoological Systematics and Evolution of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, National Science Fund for Fostering Talents in Basic Research (Special subjects in animal taxonomy, NSFC- J1210002), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada) Discovery Grant 3148.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01360

Phylogenetic analyses of horizontally transferred genes in Bd derived from bacteria and oomycete. The Bayesian inference tree is shown unrooted. The Bayesian tree is virtually identical to ML and NJ trees. Numbers at nodes represent bayesian posterior probabilities (left) and bootstrap values of maximum likelihood (middle) and neighbor-joining (right) respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate support values < 50. The scale bar corresponds to the estimated number of amino acid substitutions per site.

The code (script) and parameters used in the bioinformatic pipeline.

Exon number for each horizontally transferred gene in the two strains of Bd.

References

- Abascal F., Zardoya R., Posada D. (2005). ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics 21, 2104–2105. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen J. D., Nielsen H., von Heijne G., Brunak S. (2004). Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340, 783–795. 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger L., Speare R., Daszak P., Green D. E., Cunningham A. A., Goggin C. L., et al. (1998). Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 9031–9036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher Y., Labbate M., Koenig J. E., Stokes H. W. (2007). Integrons: mobilizable platforms that promote genetic diversity in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 15, 301–309. 10.1016/j.tim.2007.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. A., Rokas A., Slot J. C. (2012). Horizontal transfer and death of a fungal secondary metabolic gene cluster. Genome Biol. Evol. 4, 289–293. 10.1093/gbe/evs011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan T., Artzy-Randrup Y., Martin W. (2008). Modular networks and cumulative impact of lateral transfer in prokaryote genome evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10039–10044. 10.1073/pnas.0800679105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danchin E. G. J., Rosso M. N., Vieira P., de Almeida-Engler J., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B., et al. (2010). Multiple lateral gene transfers and duplications have promoted plant parasitism ability in nematodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17651–17656. 10.1073/pnas.1008486107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle R. F. (2005). Evolutionary aspects of whole-genome biology. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15, 248–253. 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman C. J., Kane K. A. (2009). DNA bridging and antibridging: a role for bacterial nucleoid-associated proteins in regulating the expression of laterally acquired genes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 587–592. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00155.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O., Brunak S., von Heijne G., Nielsen H. (2007). Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2, 953–971. 10.1038/nprot.2007.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field J., Rosenthal B., Samuelson J. (2000). Early lateral transfer of genes encoding malic enzyme, acetyl-CoA synthetase and alcohol dehydrogenases from anaerobic prokaryotes to Entamoeba histolytica. Mol. Microbiol. 38, 446–455. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D. A. (2011). Horizontal gene transfer in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 329, 1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof C., Araújo M. B., Jetz W., Rahbek C. (2011). Additive threats from pathogens, climate and land-use change for global amphibian diversity. Nature 480, 516–519. 10.1038/nature10650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P., Park K. J., Obayashi T., Fujita N., Harada H., Adams-Collier C. J., et al. (2007). WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W585–W587. 10.1093/nar/gkm259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James T. Y., Kauff F., Schoch C. L., Matheny P. B., Hofstetter V., Cox C. J., et al. (2006). Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature 443, 818–822. 10.1038/Nature05110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P. J., Palmer J. D. (2008). Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 605–618. 10.1038/Nrg2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi N., Collemare J., Lebrun M. H., Wolfe K. H. (2008). Evidence for horizontal transfer of a secondary metabolite gene cluster between fungi. Genome Biol. 9:R18. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longcore J. E., Pessier A. P., Nichols D. K. (1999). Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis gen. et sp. nov., a chytrid pathogenic to amphibians. Mycologia 91, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. J., van der Does H. C., Borkovich K. A., Coleman J. J., Daboussi M. J., Di Pietro A., et al. (2010). Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature 464, 367–373. 10.1038/Nature08850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcet-Houben M., Gabaldón T. (2010). Acquisition of prokaryotic genes by fungal genomes. Trends Genet. 26, 5–8. 10.1016/j.tig.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitreva M., Smant G., Helder J. (2009). Role of horizontal gene transfer in the evolution of plant parasitism among nematodes. Methods Mol. Biol. 532, 517–535. 10.1007/978-1-60327-853-9_30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morehouse E. A., James T. Y., Ganley A. R. D., Vilgalys R., Berger L., Murphy P. J., et al. (2003). Multilocus sequence typing suggests the chytrid pathogen of amphibians is a recently emerged clone. Mol. Ecol. 12, 395–403. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01732.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. A., Vredenburg V. T., Rachowicz L. J., Knapp R. A., Stice M. J., Tunstall T., et al. (2007). Population genetics of the frog-killing fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 13845–13850. 10.1073/pnas.0701838104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya Y., Itoh M., Okuda S., Yoshizawa A. C., Kanehisa M. (2007). KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W182–W185. 10.1093/nar/gkm321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoh N., McCutcheon J. P., Kudo T., Miyagishima S. Y., Moran N. A., Nakabachi A. (2010). Bacterial genes in the aphid genome: absence of functional gene transfer from Buchnera to its host. PLoS Genet. 6:e1000827. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pócsi I., Prade R. A., Penninckx M. J. (2004). Glutathione, altruistic metabolite in fungi. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 49, 1–76. 10.1016/S0065-2911(04)49001-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pombert J. F., Selman M., Burki F., Bardell F. T., Farinelli L., Solter L. F., et al. (2012). Gain and loss of multiple functionally related, horizontally transferred genes in the reduced genomes of two microsporidian parasites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12638–12643. 10.1073/pnas.1205020109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards T. A., Leonard G., Soanes D. M., Talbot N. J. (2011a). Gene transfer into the fungi. Fungal Biol. Rev. 25, 98–110. 10.1016/j.fbr.2011.04.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards T. A., Soanes D. M., Foster P. G., Leonard G., Thornton C. R., Talbot N. J. (2009). Phylogenomic analysis demonstrates a pattern of rare and ancient horizontal gene transfer between plants and fungi. Plant Cell 21, 1897–1911. 10.1105/tpc.109.065805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards T. A., Soanes D. M., Jones M. D., Vasieva O., Leonard G., Paszkiewicz K., et al. (2011b). Horizontal gene transfer facilitated the evolution of plant parasitic mechanisms in the oomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15258–15263. 10.1073/pnas.1105100108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J. P. (2003). MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum E. B., Poorten T. J., Joneson S., Settles M. (2012). Substrate-specific gene expression in Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, the chytrid pathogen of amphibians. PLoS ONE 7:e49924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0049924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum E. B., Stajich J. E., Maddox N., Eisen M. B. (2008). Global gene expression profiles for life stages of the deadly amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17034–17039. 10.1073/pnas.0804173105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosewich U. L., Kistler H. C. (2000). Role of horizontal gene transfer in the evolution of fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 38, 325–363. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman M., Pombert J. F., Solter L., Farinelli L., Weiss L. M., Keeling P., et al. (2011). Acquisition of an animal gene by microsporidian intracellular parasites. Curr. Biol. 21, R576–R577. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya R., Morisaka H., Kikuchi T., Takeuchi Y., Ueda M., Futai K. (2013). Secretome analysis of the pine wood nematode reveals the tangled roots of parasitism and its potential for molecular mimicry. PLoS ONE 8:e67377. 10.1371/journal.pone.0067377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siozios S., Ioannidis P., Klasson L., Andersson S. G., Braig H. R., Bourtzis K. (2013). The diversity and evolution of Wolbachia ankyrin repeat domain genes. PLoS ONE 8:e55390. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerratt L. F., Berger L., Speare R., Cashins S., McDonald K. R., Phillott A. D., et al. (2007). Spread of chytridiomycosis has caused the rapid global decline and extinction of frogs. Ecohealth 4, 125–134. 10.1007/s10393-007-0093-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slot J. C., Rokas A. (2010). Multiple GAL pathway gene clusters evolved independently and by different mechanisms in fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10136–10141. 10.1073/pnas.0914418107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slot J. C., Rokas A. (2011). Horizontal transfer of a large and highly toxic secondary metabolic gene cluster between fungi. Curr. Biol. 21, 134–139. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer E. L., von Heijne G., Krogh A. (1998). A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 6, 175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strope P. K., Nickerson K. W., Harris S. D., Moriyama E. N. (2011). Molecular evolution of urea amidolyase and urea carboxylase in fungi. BMC Evol. Biol. 11:80. 10.1186/1471-2148-11-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B. F., Xiao J. H., He S., Liu L., Murphy R. W., Huang D. W. (2013). Multiple interkingdom horizontal gene transfers in Pyrenophora and closely related species and their contributions to phytopathogenic lifestyles. PLoS ONE 8:e60029. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G. L., Yang Z. F., Kosch T., Summers K., Huang J. L. (2011). Evidence for acquisition of virulence effectors in pathogenic chytrids. BMC Evol. Biol. 11:195. 10.1186/1471-2148-11-195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W. J., Fernandez J. G., Sohn J. J., Amemiya C. T. (2015). Chitin is endogenously produced in vertebrates. Curr. Biol. 25, 897–900. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trcek J., Matsushita K. (2013). A unique enzyme of acetic acid bacteria, PQQ-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase, is also present in Frateuria aurantia. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 7369–7376. 10.1007/s00253-013-5007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Does H. C., Rep M. (2012). Horizontal transfer of supernumerary chromosomes in fungi. Methods Mol. Biol. 835, 427–437. 10.1007/978-1-61779-501-5_26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake D. B., Vredenburg V. T. (2008). Are we in the midst of the sixth mass extinction? A view from the world of amphibians. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11466–11473. 10.1073/pnas.0801921105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D. D., Zhang Y. P. (2011). Eukaryotic origin of a metabolic pathway in virus by horizontal gene transfer. Genomics 98, 367–369. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Xu C., Lu H. L., Chen X., St Leger R. J., Fang W. (2014). Host-to-pathogen gene transfer facilitated infection of insects by a pathogenic fungus. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004009. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Zhou Q., Xie G. L., Zhang G. Q., Zhang X. W., Wang Y. L., et al. (2012). Interkingdom gene transfer may contribute to the evolution of phytopathogenicity in botrytis cinerea. Evol. Bioinform. 8, 105–117. 10.4137/Ebo.S8486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Phylogenetic analyses of horizontally transferred genes in Bd derived from bacteria and oomycete. The Bayesian inference tree is shown unrooted. The Bayesian tree is virtually identical to ML and NJ trees. Numbers at nodes represent bayesian posterior probabilities (left) and bootstrap values of maximum likelihood (middle) and neighbor-joining (right) respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate support values < 50. The scale bar corresponds to the estimated number of amino acid substitutions per site.

The code (script) and parameters used in the bioinformatic pipeline.

Exon number for each horizontally transferred gene in the two strains of Bd.