Abstract

Immunosenescence is a hallmark of the aging immune system, leading to increased susceptibility to infections in the aged population and decreased ability to eradicate infectious pathogens. These effects, in turn, result in an increased burden on the healthcare system due to elevated frequency and duration of hospital visits. Growing evidence suggests that cells of the innate immune system are central modulators for the initiation and maintenance of an adequate pathogen-specific response through the adaptive immune system. While there are many reports on age-dependent alterations and dysfunctions of the adaptive immune system, the underlying mechanisms and effects of natural aging on the composition of the innate immune system remain unknown. Here, we present the results obtained from the comprehensive immunophenotyping of innate leukocyte populations, examined for age-related alterations within different sub-populations assessed using multi-parametric flow cytometry. We compared peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 24 young (aged 19–30 years) and 26 elderly (aged 53–67 years) donors. For classical CD16+CD56dim NK cells, the fraction of CD62L+CD57+ was diminished in the elderly donors compared with young individuals, while the other investigated NK subsets remained unaffected by age. Both transitional monocytes and non-classical CD14+–CD16++ monocytes were increased in the elderly compared with the young. The populations of pDCs and mDC2 were decreased among the elderly. These data demonstrate that the dynamics of the mDC subsets might counteract decreased virus surveillance. Furthermore, these data show that the maturation of NK cells might gradually slow down.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9828-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aging, Immune cell subsets, Innate immunity, Dendritic cells, Monocytes, Flow cytometry

Introduction

The immune system protects individuals from invading pathogens and ensures the removal of these organisms in case of successful entry into the host organism. The adaptive arm of the immune system is characterized by the somatic recombination of receptor genes, generating lymphocyte populations, namely T and B cells, carrying highly diverse antigen receptors. The innate arm recognizes pathogens through invariant, germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRR), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs). The appropriate activation of innate immune cells is crucial for the establishment of subsequent adaptive immune responses.

The human immune system undergoes a multitude of age-related changes, referred to as immunosenescence. While age-dependent processes can be observed in the adaptive immune system, as investigated and discussed in a parallel study (Stervbo et al. 2015), little is known about age-dependent processes in the cells of the innate immune system, such as natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, granulocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs). Principally, in circulation, these cells have a higher turnover compared with lymphocytes, but in tissue monocytes, the cells differentiate into long-lived macrophages and/or DCs (Yona et al. 2013).

Different sub-populations of human monocytes can be identified through the differential expression of CD14 and CD16 (Cros et al. 2010). Monocytes characterized by the expression CD14++CD16− are defined as classical, inflammatory cells, while CD14+–CD16++ cells are defined as non-classical, resident subsets. In addition, CD14++CD16+ double-positive cells represent a transitional subset (Ziegler-Heitbrock et al. 2010). Although all three populations show diverging potential in terms of macrophage and DC cell differentiation, the induction of T cell proliferation might be similar (Zawada et al. 2011; Ziegler-Heitbrock and Hofer 2013). Previous data have demonstrated age-dependent changes in monocyte sub-populations (Seidler et al. 2010; Nyugen et al. 2010).

Several DC subsets have been described, with a general separation into plasmacytoid (pDCs) and myeloid, or classical, DCs (mDCs) (Collin et al. 2011). There is conflicting information concerning the effects of aging on the different DC subsets. Some reports have demonstrated a decrease in pDC numbers with age (Shodell and Siegal 2002; Jing et al. 2009; Orsini et al. 2012), while other reports did not show differences (Bella et al. 2007; Agrawal et al. 2007). Similarly, mDC numbers in adults either decrease with age (Bella et al. 2007) or show no alterations (Agrawal et al. 2007; Jing et al. 2009; Orsini et al. 2012).

NK cells recognize and lyse virus-infected cells. These cells are divided into two main subsets based on CD56 expression: cytotoxic CD16+CD56dim NK cells and cytokine-producing CD16−CD56bright NK cells (Long et al. 2013). The total numbers of NK cells increase with age (Almeida-Oliveira et al. 2011; Solana et al. 2012), reflecting a change in the ratio of CD56dim/CD56bright (Hayhoe et al. 2010) through an increasing fraction of CD56dim cells and a decreasing fraction of the CD56bright population (Borrego et al. 1999; Chidrawar et al. 2006; Le Garff-Tavernier et al. 2010; Almeida-Oliveira et al. 2011). However, some reports did not observe any significant alterations of either population (Chidrawar et al. 2006).

The current knowledge on age-dependent alterations of the innate immune system either originated from studies investigating immune reactions in cohorts with a large age spread or from experimental settings where the immune composition of old adults (>65 years) is compared with a young population, i.e., individuals in their twenties. Thus, little is known about age-associated differences in the innate immune system throughout adulthood, including middle-aged individuals at steady state. Here, we report the fraction and cell count of innate immune cells, namely monocytes, DCs, and NK cells in healthy adult donors. We observed that transitional monocytes and non-classical CD14+–CD16++ monocytes are increased in the elderly donors compared with young individuals. In contrast, pDC and mDC2 sub-populations were smaller in the elderly. No difference was observed in CD56dim and CD56bright NK cells or their sub-populations, except for a decrease in the CD62L+ CD57+ subset among CD56dim NK cells.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

The samples were obtained in the fall of 2011 from the PRIMAGE study cohort at Berlin-Brandenburg Center for Regenerative Therapies, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The study was approved by the ethics board of the Charité (approval number EA 1/175/11). All study participants gave their written informed consent prior to enrolment for the study. A total of 50 donors were recruited, with no minors under the age of 18 participating. All study participants were healthy adults and aged between 19 and 67 years. Individuals who were receiving immunomodulatory therapy, having hemoglobin values lower than 12 g/dl, or who were pregnant were not enrolled for the study. The final cohort consisted of 24 young donors (19–30 years, 12 females, 12 males) and 26 elderly donors (53–67 years, 16 females, 10 males), and its characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. From each donor, a total of 100 ml blood was drawn using 10 ml Lithium-Heparin Vacutainers (BD Biosciences) and processed immediately.

Preparation of PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were prepared from whole blood using Leucosept Tubes (Cellstar) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, separations tubes were filled with 15-ml Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare) followed by addition heparinized blood pre-diluted in a 1:1 ratio with PBS (Gibco). The tubes were centrifuged at 800×g for 15 min at room temperature. PBMCs were then isolated and washed twice with PBS.

Antibodies and staining procedure

Isolated PBMCs were stained with optimal dilutions of CD45-VioGreen (Clone: 5B1; Miltenyi Biotec), HLA-DR-Vioblue (Clone: AC122; Miltenyi Biotec), CD14-PE-Vio770 (Clone: TÜK4; Miltenyi Biotec), CD16-APC-H7 (Clone: 3G8; BD Biosciences), BDCA1-APC (Clone: AD5-8E7; Miltenyi Biotec), BDCA2-FITC (Clone: AC144; Miltenyi Biotec), and BDCA3-PE (Clone: AD5-14H12; Miltenyi Biotec) for analysis of DCs and monocytes. A dump channel consisted of CD3-PerCp (Clone: BW264/56; Miltenyi Biotec), CD20-PerCp (Clone: LT20; Miltenyi Biotec), and CD56-PerCpCy5.5 (Clone: HCD56; BioLegend). In this panel, dead cells were excluded by addition of PI (BD Biosciences) prior to sample acquisition on MACS Quant (Miltenyi Biotec) flow cytometer equipped with blue 488 nm, red 633 nm, and violet 405 nm lasers.

For analysis of NK cells, a dump channel consisting of CD3-VioGreen (Clone: BW264/56; Miltenyi Biotec), CD14-VioGreen (Clone: TÜK4; Miltenyi Biotec), and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen) was used together with CD16-APC-H7 (Clone: 3G8; BD Biosciences), CD56-BV421 (Clone: HCD56; BioLegend), CD62L-FITC (Clone: 145/15; Miltenyi Biotec), CD57-PE (Clone: TB03; Miltenyi Biotec), CD69-PECy7 (Clone: FN50; BioLegend), CD27-APC (Clone: M-T271; Miltenyi Biotec), and Ki67-PerCpCy5.5 (Clone: B56; BD Biosciences). All surface staining was performed in PBS at 107 cells/ml for 15 min at room temperature. Prior to staining with antibodies, unspecific antibody binding was blocked with Beriglobin (ZLB Behring) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. Dead cells were marked with LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml prior to fixation with the formaldehyde containing FACS-Lysing-Solution (BD Biosciences) for 10 min at room temperature. After permeabilization with FACS-Perm-Solution (BD Biosciences) for 10 min at room temperature, Ki67 was stained intracellular for 30 min at room temperature in FACS-Perm-Solution. Samples were acquired on a MACS Quant (Miltenyi Biotec) flow cytometer equipped with blue 488 nm, red 633 nm, and violet 405 nm lasers.

Statistics

FACS data was analyzed using FlowJo version 9.6.4 (Tree Star) and statistical analysis was performed using R, version 2.15 (R Core Team 2012). p values <0.05 were considered significant. Plots were generated with the R-package ggplot2 (Wickham 2009).

Results

We analyzed the composition of innate immune cells in the peripheral blood of healthy donors. PBMCs were isolated from the blood of 24 young (aged 19–30 years) and 26 elderly (aged 53–67 years) healthy donors of the PRIMAGE study cohort at the Berlin-Brandenburg Center for Regenerative Therapies, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. For practical reasons, blood from only 24 donors facilitated the complete analysis of NK cells. This group contained 11 young (aged 23–30 years) and 13 elderly (aged 53–64 years) individuals. The mean and standard deviation of all of the analyzed populations, together with the p values for comparison, are summarized in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

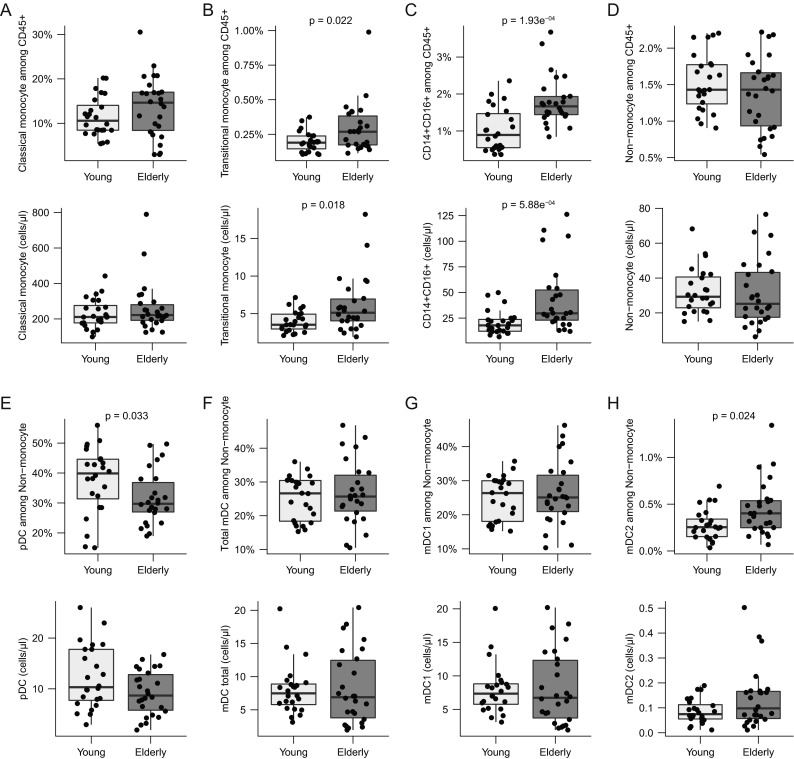

Increased CD14++CD16+ transitional and CD14+–CD16++ non-classical monocytes in elderly donors

PBMCs were stained for CD14 and CD16 to discriminate between CD14++CD16− classical, CD14+CD16+ transitional, and CD14+–CD16++ non-classical resident monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1). T cells, B cells, and NK cells were excluded in a dump channel using anti-CD3, anti-CD20, and anti-CD56 antibodies, and granulocytes lacking HLA-DR expression were also excluded (Supplementary Fig. 1; Abeles et al. 2012). Classical monocytes showed higher frequencies in the elderly, but this effect and any observed differences in cell count were insignificant (Fig. 1a). Both transitional monocytes and CD14+–CD16++ non-classical monocytes were increased in frequency and number in the elderly group compared with the young group (Fig. 1b, c).

Fig. 1.

Monocytes and DCs. Cells were gated as described in Supplementary Fig. 1. Shown are boxplots for frequencies and total cell numbers/microliter whole blood for a CD14++CD16− classical monocytes; b CD14++CD16+ transitional monocytes; c CD14+–CD16++ non-classical monocytes; d non-monocytes; e pDC; f total mDC; g mDC1; h mDC2. The box indicates the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; the whiskers the minimum and maximum values excluding outliers. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for differences and p values <0.05 are reported

Fewer pDCs and increased mDC2 sub-populations in elderly individuals compared with young donors

CD14−CD16− non-monocytes were further divided into BDCA2+BDCA3− pDCs, BDCA2−BDCA3−BDCA1+ type 1 mDC1s, and BDCA2−BDCA3+BDCA1+ mDC2s (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). In the elderly, both the frequency and absolute cell count for pDCs were lower (Fig. 1f). Inversely, the mDC2 frequencies among the non-monocytes and total counts were significantly higher in this group (Fig. 1g). The mDC1 sub-population and CD14−CD16− non-monocytes did not differ between the two age groups (Fig. 1d, f).

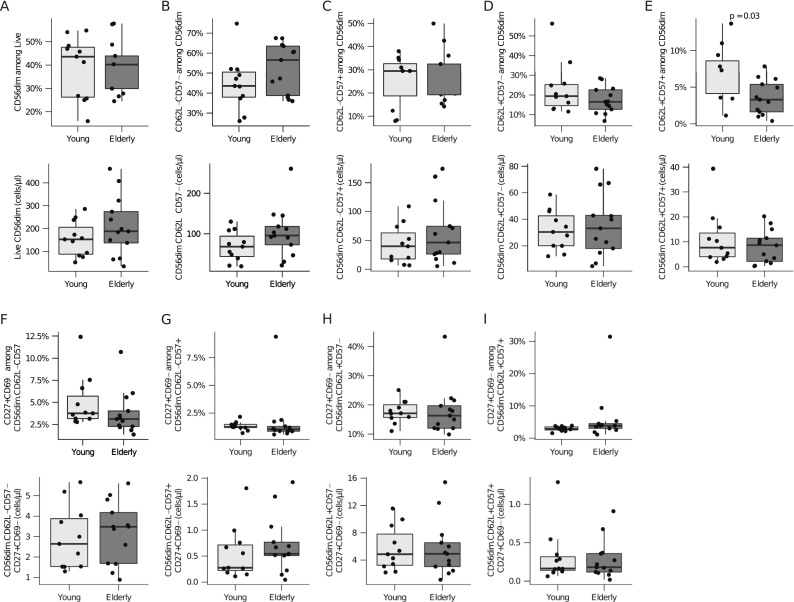

Minor differences in NK cell sub-populations

NK cells were identified based on the expression of CD56 and separated into mature and generally cytotoxic CD16+CD56dim cells and cytokine-producing CD16−CD56bright cells for further analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). None of the analyzed donors showed activated NK cells in circulation, as demonstrated by the absence of CD69+ expression in all CD56 sub-populations (data not shown). A tendency towards lower fractions, but higher counts, of CD16+CD56dim cells was observed in the elderly group (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

CD56dim NK cells. Cells were gated as described in Supplementary Fig. 2. Shown are boxplots for frequencies and total cell numbers/microliter whole blood for a CD56dim; b CD62L−CD57−; c CD62L−CD57+; d CD62L+CD57−; e CD62L+CD57+; f CD27+CD69−CD62L−CD57−; g CD27+CD69−CD62L−CD57+; h CD27+CD69−CD62L+CD57−; i CD27+CD69−CD62L+CD57+. The box indicates the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; the whiskers the minimum and maximum values excluding outliers. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for differences and p values <0.05 are reported

To further assess the maturation and functional status of the CD56+ NK cells, the cells were stained for CD62L and CD57. Expression of CD62L gradually declines with increasing CD57 expression in NK cells and marks a gradual maturation from cytokine producers to completely cytotoxic NK cells (Juelke et al. 2010; Nielsen et al. 2013). Thus, CD56+ NK cells might exist in four maturation stages: fully immature CD62L−CD57− cells, immature CD62L+CD57− cells, transitional CD62L+CD57+ cells, and fully mature CD62−CD57+ cells (Luetke-Eversloh et al. 2013).

Among CD16+CD56dim NK cells, the proportion of the transitional CD62L+CD57+ sub-population was significantly lower in the elderly (Fig. 2e), corresponding to an insignificant increase in the frequencies of fully immature CD62L−CD57− cells (Fig. 2b). The proportion of CD62L+CD57− immature and CD62L−CD57+ fully mature NK cells was comparable between the two age groups (Fig. 2c, d). Although the proportion of the CD62L+CD57+ sub-population was significantly lower in the elderly, the cell counts were similar for both groups (Fig. 2e). The expression of CD27, identifying naïve NK cells, did not differ between young and elderly individuals in the previously described sub-populations analyzed (Fig. 2f–i). In addition, no age-related differences were observed in the proliferative behavior of NK cell subsets based on the expression of Ki67 (Supplementary Fig. 3a–e).

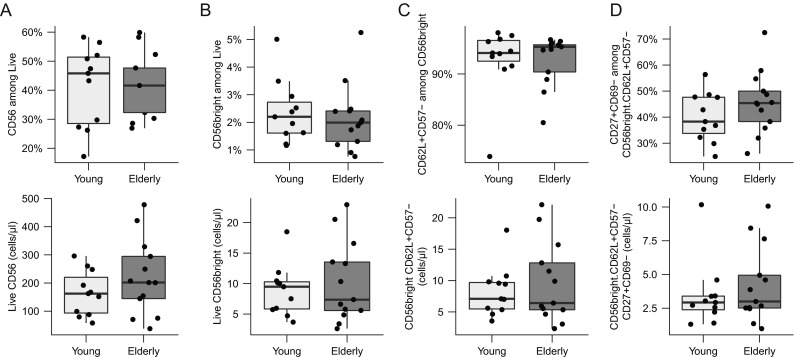

For the more immature CD16−CD56bright cells, a tendency towards lower fractions and cell counts was observed (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, no age-associated alterations were observed in CD62L+CD57− (Fig. 3b), CD27+CD69− (Fig. 3c), or Ki67+ (Supplementary Fig. 1f) cells.

Fig. 3.

CD56bright NK cells. Cells were gated as described in Supplementary Fig. 2. Shown are boxplots for frequencies and total cell numbers/microliter whole blood for a total CD56; b CD56bright; c CD62L+CD57−; d CD27+CD69−CD62L+CD57−. The box indicates the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; the whiskers the minimum and maximum values excluding outliers. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to test for differences and p values <0.05 are reported

Discussion

In addition to age-related changes in the adaptive immune system addressed in part II of this two-part continuing PRIMAGE study (Stervbo et al. 2015), we analyzed qualitative and quantitative immunophenotypical changes within the innate leukocyte compartment, including sub-populations of monocytes, DCs, and NK cells. We reported the effect of aging on the mDC sub-populations mDC1 and mDC2 and the double expression of CD62L and CD57 among NK cells. We reported the first evidence of an increase in mDC2 cells and a decrease in transitional CD62L+CD57+ cells among CD56dim NK cells.

Although aging is a continuous process, much attention has been paid to the elderly (i.e., older than 65 years) because of increased susceptibility to infections and an impaired response to vaccines (Montecino-Rodriguez et al. 2013). However, little is known about the immune phenotype of the immune systems of late middle-aged individuals. It is clear that age-related alterations might be less prominent in the elderly than in the old; for instance, the diversity of T cells dramatically decreases after the age of 70 (Weiskopf et al. 2009). However, it is also clear that age strongly correlates with comorbidities in an exponential fashion (Niccoli and Partridge 2012). Thus, the age group used in the PRIMAGE study is less likely affected through comorbidity.

The role of gender together with aging in shaping the adaptive immune system is unknown. Although differences in immune responses between men and women have been observed (Nalbandian and Kovats 2005; Furman et al. 2014), assessment of the contribution of gender to alteration of the immune system is outside of the scope of the PRIMAGE study.

We observed a significant increase in the frequency of transitional and CD14+–CD16++ non-classical monocytes in the elderly compared with the young. This observation is consistent with previous studies showing an age-dependent decrease of classical monocytes, while minor subsets increased correspondingly (Seidler et al. 2010; Nyugen et al. 2010). However, the authors made no discrimination between CD14+–CD16++ and CD14++CD16+ monocytes. A recent report described age-related alterations in the composition of the monocyte subset in 76 individuals aged 20–82 years (Hearps et al. 2012). The authors reported increasing frequencies of both transitional and non-classical CD14+–CD16++ monocytes and decreasing frequencies of classical monocytes associated with the higher age of the donors. Consistent with the findings presented here, no age-dependent alterations of the proportion or cell density of classical CD14++CD16− cells were observed.

Increased non-classical CD14+–CD16++ monocytes have been associated with rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular diseases (Yang et al. 2014). However, the data presented here suggested that the observed disease association is rather an association with age. It would be interesting to follow the PRIMAGE cohort and determine whether there is a disease risk associated with the measured levels of CD14+–CD16++ non-classical monocytes.

We observed smaller pDCs populations in the elderly compared with the young, consistent with other reports describing an age-dependent decrease of pDCs (Shodell and Siegal 2002; Jing et al. 2009; Orsini et al. 2012), although some groups have reported diverging observations (Bella et al. 2007; Agrawal et al. 2007).

The results of the present study provide the first evidence of the effect of aging on the mDC sub-populations mDC1 and mDC2. We demonstrated an increase in the mDC2 population, while the mDC1 population remained unchanged throughout the analyzed age groups. While this change was observed in the mDC2/mDC1 ratio, the CD14−CD16−BDCA1+ non-monocyte mDCs did not change with age (data not shown), consistent with the results of previous reports on this subject (Agrawal et al. 2007; Jing et al. 2009; Orsini et al. 2012). Only a single report has demonstrated a decrease in both the fraction and cell count in total adult mDCs (Bella et al. 2007), potentially reflecting differences in the markers used for the identification of total mDCs. Notably, in a previous study, children possessed higher frequencies of mDCs compared with adults (Orsini et al. 2012). This observation indicates that a contraction of the mDC population occurs early in life. The mDC2 populations respond to ligands of TLR3, TLR7/8, and TLR9 through the production of high amounts of INFλ (Hémont et al. 2013; Nizzoli et al. 2013). Thus, the data presented here demonstrate that the increase in the mDC2 population might maintain virus surveillance, indicating a compensation for diminished immunocompetence in the elderly.

Within the NK cell compartment, the ratio of CD56dim/CD56bright cells increases with age (Borrego et al. 1999; Chidrawar et al. 2006; Hayhoe et al. 2010; Le Garff-Tavernier et al. 2010; Juelke et al. 2010; Almeida-Oliveira et al. 2011). We also detected slightly increased numbers of CD16+CD56dim cells. The expression of CD57 and CD62L cells has been associated with the gradual maturation of NK cells (Luetke-Eversloh et al. 2013). CD57 might be expressed on highly cytotoxic NK cells (Nielsen et al. 2013), while CD62L+CD56dim might produce the essential cytokines INFγ and TNFα (Juelke et al. 2010). We observed decreased CD62L+CD57+ expression among CD56dim cells, with a slight increase in CD62L−CD57−, and no change in CD62L+CD57− or CD62L−CD57+. It has previously observed that the total fraction of CD56dimCD62L+ among CD56+ NK cells increases with age (Juelke et al. 2010). However, this observation might reflect a general increase in CD56dim cells. CD57 either increases or remains unchanged with age (Hayhoe et al. 2010; Le Garff-Tavernier et al. 2010). The analysis of the NK compartment revealed an apparent slowdown of the maturation process of NK cells within the CD56dim population.

Similarly to the age-associated changes described for the adaptive immune system, the composition of the innate immune system is subject to dynamic changes throughout life. The data presented here suggest that these alterations do not uniformly affect all cell types, but rather display substantial variations between the different leukocyte subsets. Together with data from the companion paper (Stervbo et al. 2015), it is apparent that immunocompetence does not simply decrease with age, but is modulated to counteract detrimental alterations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 1.12 MB)

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the BCRT Flow Cytometry Lab. The study was supported by the BMBF GerontoSys (Verbundprojekt PRIMAGE).

Conflict of interest

We have no competing interests.

Author’s contributions

S.M., J.M., C.B., D.R., M.N., and A.S. performed the experiments. U.S., C.B., D.R., K.J., and U.B. performed the analysis. S.O., N.B., A.G., A.N., and A.T. conceptualized the overall strategy and developed clinical translation and implementation. All of the authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. U.S. drafted the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- DC

Dendritic cell

- pDC

Plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- mDC

Myeloid dendritic cell

- NK

Natural killer cells

Footnotes

Ulrik Stervbo, Sarah Meier and Julia Nora Mälzer contributed equally to this work.

References

- Abeles RD, McPhail MJ, Sowter D, et al. CD14, CD16 and HLA-DR reliably identifies human monocytes and their subsets in the context of pathologically reduced HLA-DR expression by CD14(hi) /CD16(neg) monocytes: expansion of CD14(hi)/CD16(pos) and contraction of CD14(lo)/CD16(pos) monocytes in acute liver failure. Cytometry A. 2012;81:823–834. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Cao J-N, et al. Altered innate immune functioning of dendritic cells in elderly humans: a role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-signaling pathway. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2007;178:6912–6922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Oliveira A, Smith-Carvalho M, Porto LC, et al. Age-related changes in natural killer cell receptors from childhood through old age. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bella SD, Bierti L, Presicce P, et al. Peripheral blood dendritic cells and monocytes are differently regulated in the elderly. Clin Immunol (Orlando, Fla.) 2007;122:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego F, Alonso MC, Galiani MD, et al. NK phenotypic markers and IL2 response in NK cells from elderly people. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:253–265. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(98)00076-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chidrawar SM, Khan N, Chan YLT, et al. Ageing is associated with a decline in peripheral blood CD56bright NK cells. Immun Ageing. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin M, Bigley V, Haniffa M, Hambleton S. Human dendritic cell deficiency: the missing ID? Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:575–583. doi: 10.1038/nri3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cros J, Cagnard N, Woollard K, et al. Human CD14dim monocytes patrol and sense nucleic acids and viruses via TLR7 and TLR8 receptors. Immunity. 2010;33:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman D, Hejblum BP, Simon N, et al. Systems analysis of sex differences reveals an immunosuppressive role for testosterone in the response to influenza vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:869–874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayhoe RPG, Henson SM, Akbar AN, Palmer DB. Variation of human natural killer cell phenotypes with age: identification of a unique KLRG1-negative subset. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearps AC, Martin GE, Angelovich TA, et al. Aging is associated with chronic innate immune activation and dysregulation of monocyte phenotype and function. Aging Cell. 2012;11:867–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2012.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hémont C, Neel A, Heslan M, et al. Human blood mDC subsets exhibit distinct TLR repertoire and responsiveness. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93:599–609. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0912452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Shaheen E, Drake RR, et al. Aging is associated with a numerical and functional decline in plasmacytoid dendritic cells, whereas myeloid dendritic cells are relatively unaltered in human peripheral blood. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juelke K, Killig M, Luetke-Eversloh M, et al. CD62L expression identifies a unique subset of polyfunctional CD56dim NK cells. Blood. 2010;116:1299–1307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Garff-Tavernier M, Béziat V, Decocq J, et al. Human NK cells display major phenotypic and functional changes over the life span. Aging Cell. 2010;9:527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long EO, Sik Kim H, Liu D, et al. Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:227–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetke-Eversloh M, Killig M, Romagnani C. Signatures of human NK cell development and terminal differentiation. Front Immunol. 2013;4:499. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecino-Rodriguez E, Berent-Maoz B, Dorshkind K. Causes, consequences, and reversal of immune system aging. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:958–965. doi: 10.1172/JCI64096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalbandian G, Kovats S. Understanding sex biases in immunity: effects of estrogen on the differentiation and function of antigen-presenting cells. Immunol Res. 2005;31:91–106. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:2:091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niccoli T, Partridge L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R741–R752. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen CM, White MJ, Goodier MR, Riley EM. Functional significance of CD57 expression on human NK cells and relevance to disease. Front Immunol. 2013;4:422. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nizzoli G, Krietsch J, Weick A, et al. Human CD1c+ dendritic cells secrete high levels of IL-12 and potently prime cytotoxic T-cell responses. Blood. 2013;122:932–942. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyugen J, Agrawal S, Gollapudi S, Gupta S. Impaired functions of peripheral blood monocyte subpopulations in aged humans. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:806–813. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9448-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini G, Legitimo A, Failli A, et al. Enumeration of human peripheral blood dendritic cells throughout the life. Int Immunol. 2012;24:347–356. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seidler S, Zimmermann HW, Bartneck M, et al. Age-dependent alterations of monocyte subsets and monocyte-related chemokine pathways in healthy adults. BMC Immunol. 2010;11:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shodell M, Siegal FP. Circulating, interferon-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells decline during human ageing. Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:518–521. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solana R, Tarazona R, Gayoso I, et al. Innate immunosenescence: effect of aging on cells and receptors of the innate immune system in humans. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stervbo U, Bozzetti C, Baron U et al (2015) Effects of aging on human leukocytes (part II): immunophenotyping of adaptive immune B and T cell subsets. Age. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9829-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Weiskopf D, Weinberger B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. The aging of the immune system. Transpl Int Off J Eur Soc Organ Transplant. 2009;22:1041–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis, 1st ed. 2009. Corr. 3rd printing 2010. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang L, Yu C, et al. Monocyte and macrophage differentiation: circulation inflammatory monocyte as biomarker for inflammatory diseases. Biomark Res. 2014;2:1. doi: 10.1186/2050-7771-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yona S, Kim K, Wolf Y et al (2013) Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity 38:79–91. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, Rotter B, et al. SuperSAGE evidence for CD14++CD16+ monocytes as a third monocyte subset. Blood. 2011;118:e50–e61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-326827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Hofer TPJ. Toward a refined definition of monocyte subsets. Front Immunol. 2013;4:23. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116:e74–e80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-258558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1.12 MB)