Abstract

This study evaluated the effect of resistance training (RT) volume on muscular strength and on indicators of abdominal adiposity, metabolic risk, and inflammation in post-menopausal women (PW). Thirty-two volunteers were randomly allocated into the following three groups: control (CT, no exercise, n = 11), low-volume RT (LV, three sets/exercise, n = 10), and high-volume RT (HV, six sets/exercise, n = 11). The LV and HV groups performed eight exercises at 70 % of one maximal repetition, three times a week, for 16 weeks. Muscular strength and indicators of abdominal adiposity, metabolic risk, and inflammation were measured at baseline and after 16 weeks. No differences were found in baseline measures between the groups. The PW showed excess weight and fat percentage (F%), large waist circumference (WC), high waist-hip ratio (WHR), and hypercholesterolemia and borderline values of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c%). Following the RT, a similar increase in muscle strength and reduction in F% from baseline were found in both trained groups. In HV, a decrease in total cholesterol, LDL-c, WC, and WHR was noted. Moreover, the HV showed a lower change (delta%) of interleukin-6 (IL-6) when compared to CT (HV = 11.2 %, P25–75 = −7.6–28.4 % vs. CT = 99.55 %, P25–75 = 18.5–377.0 %, p = 0.049). In LV, a decrease was noted for HbA1c%. There were positive correlations (delta%) between WHR and IL-6 and between IL-6 and TC. These results suggest that while a low-volume RT improves HbA1c%, F%, and muscular strength, a high-volume RT is necessary to improve indicators of abdominal adiposity and lipid metabolism and also prevent IL-6 increases in PW.

Keywords: Exercise, Sarcopenia, Obesity, Glycosylated hemoglobin, Menopause

Introduction

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends resistance training (RT; two to three times a week, eight to ten exercises, and one to three sets of 8–15 repetitions at 60–80 % of one repetition maximum) to improve muscular mass and strength and avoid sarcopenia in the elderly (American College of Sports 2009; Garber et al. 2011). Another well-established benefit of RT is the prevention of abdominal and total fat gain and increases in markers of both inflammation and metabolic risk factors (American College of Sports 2009; Garber et al. 2011; Lera Orsatti et al. 2014; Maesta et al. 2007; Orsatti et al. 2010a; Phillips et al. 2012; Senechal et al. 2012). However, it has been established that a higher volume (amount) of exercise (or higher energy expenditure) reduces abdominal fat and metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese people (American College of Sports 2009; Friedenreich et al. 2015; Garber et al. 2011; Lera Orsatti et al. 2014; Nimmo et al. 2013).

In RT, the energy cost of one set of 8–15 repetitions of eight resistance training exercises is 70–80 kcal in young and elderly women (Haddock and Wilkin 2006; Phillips and Ziuraitis 2004). Even adding post-exercise oxygen consumption, a three-set RT protocol performed two to three times a week may not be enough to meet the recommendations of minimal energy expenditure per week (1200 kcal; American College of Sports et al. 2009; Garber et al. 2011). Moreover, the number of transitions from rest to exercise in intermittent exercise (such as RT) has been suggested (Combes et al. 2015) to be critical to lead to sufficient metabolic fluctuations for activation of important signaling proteins that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis in young adults (Braun and Schulman 1995). Thereby, resistance exercise volume has been shown to be positively associated with activation of signaling pathways that regulate PGC-1α (Ahtiainen et al. 2015). Ahtiainen et al. showed that ten sets of RT induced greater activation of signaling pathways that regulate PGC-1α when compared to five sets. Collectively, these data have suggested that low-volume RT (up to three sets) may lead to insufficient metabolic fluctuations for activation of signaling proteins that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis. As the reductions in body fat and metabolic risk factors appear to be directly associated with either an enhancement of the muscle aerobic function (mitochondrial content) (Kelley 2005; Wisloff et al. 2005) or (and) a higher-energy expenditure (Friedenreich et al. 2015; Nimmo et al. 2013), three-set RT protocol may not be enough to promote reduction in body fat and metabolic risk factors (Davidson et al. 2009; Lera Orsatti et al. 2014; Nimmo et al. 2013; Slentz et al. 2011). However, increasing the number of total sets in a RT protocol while keeping the same load (intensity) corresponds to an increased volume/energy expenditure (American College of Sports 2009; Garber et al. 2011; Haddock and Wilkin 2006) and a sufficient metabolic fluctuation for activation of signaling proteins that regulate mitochondrial biogenesis (Ahtiainen et al. 2015). Thus, it would seem reasonable to assume that performing RT with the double the volume (from three to six sets) is an important stimulus for promoting positive effects on indicators of body fat and metabolic risk.

Post-menopausal women (PW) may obtain unique benefits from RT with a higher volume because menopause is accompanied by changes in body composition which are characterized by an increase in body fat, especially at the abdomen, and progressive reduction in strength and muscle mass (sarcopenia; Kamel et al. 2002; Pfeilschifter et al. 2002; Sirola and Rikkonen 2005; Toth et al. 2000). Abdominal obesity gain increases the risk of post-menopausal endometrial, colon, and breast cancers (Hartz et al. 2012; Krishnan et al. 2013). Moreover, abdominal obesity is a pro-inflammatory state that contributes to the development of components of metabolic syndrome (dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and high blood pressure), which are important risk factors of cardiovascular diseases, the major cause of death among PW (Eguchi et al. 2012; Hartz et al. 2012; Orsatti et al. 2010b; Petri Nahas et al. 2009; Pfeilschifter et al. 2002; Zhang et al. 2008). High serum levels of inflammation factors released by adipose tissue, such as interleukin (IL)-6, have been reported to predict disability and sarcopenia, independently of other known risk factors (Gallucci et al. 2007), particularly in older women (Ferrucci et al. 2002; Payette et al. 2003). Sarcopenia is usually associated with functional impairment and physical disabilities among elderly women, and it has been associated with an increased risk of falls and osteoporotic fractures (Rantanen 2003; Sirola and Rikkonen 2005).

Understanding the relationship between variables of training (i.e., amount of exercise or volume) and physiologic adaptations is important to develop effective training protocols (American College of Sports et al. 2009; Garber et al. 2011). The dose-response benefits of exercise can be well estimated from controlled and randomized trials. However, none of the controlled and randomized trials have been designated to compare volumes over the three sets of RT on body fat and metabolic risk factors in PW. Therefore, to confirm the effects of RT volume beyond traditional RT protocol, we investigated the effects of two different RT volumes (three sets vs. six sets) on pro-inflammatory cytokines, muscular strength performance and indicators of abdominal adiposity, and glucose and lipid metabolism in PW. We hypothesized that high-volume RT would elicit greater improvement when compared to low-volume RT in the variables mentioned above.

Methods

Subjects and design of the study

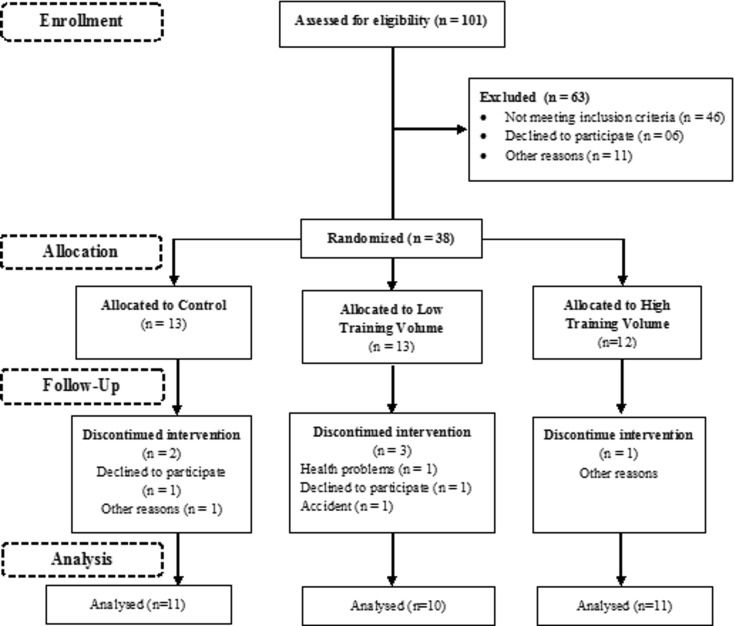

This randomized and controlled study was concluded with 32 of 101 women, aged >45 years, selected at a neighborhood association near the Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro, Brazil (Fig. 1). All volunteers included were PW aged 50 or older, characterized by spontaneous amenorrhea for at least 12 months, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level greater than 40 mIU/ml. The inclusion criteria consisted of no hormone therapy or phytoestrogens; controlled blood pressure and glycemia; absence of myopathies, arthropathies, and neuropathies; absence of muscle, thromboembolic, and gastrointestinal disorders; absence of cardiovascular and infection diseases; non-drinker; and non-smoker. Prior to the study, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxin (T4) levels were measured to exclude thyroid dysfunctions. All selected women agreed with the terms of the study and signed the free and informed consent approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro, Brazil. The initial evaluation consisted of questionnaires and an interview. Data collected included information about behavioral habits, history of illnesses and medicine intake, nutritional habits, and physical activity. After the initial assessment, all the volunteers were randomly divided into the following three groups: control (CT, n = 13), low volume (LV, n = 13), and high volume (HV, n = 12). Six women dropped out of study (accident, health-related, and personal problems); therefore, the final sample size was 32 women, CT, n = 11; LV, n = 10, and HV, n = 11. Of the 32 women, 20 medication users were identified. Four used glucose-lowering drugs (CT = 1, LV = 2, and HV = 1), five used lipid-lowering drugs (CT = 2, LV = 2, and HV = 1), four used anti-inflammatory drugs (CT = 1, LV = 2, and HV = 1), and 16 used blood pressure-lowering drugs (CT = 5, LV = 6, and HV = 5).

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram

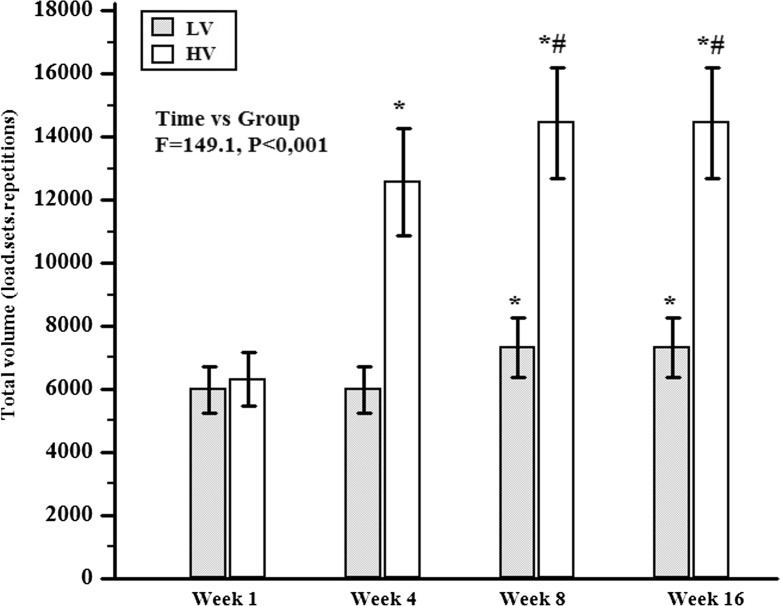

The CT group performed stretching activities twice a week and did not participate in the RT routine. The LV group performed a RT protocol constituted of three sets of 8–12 repetitions at 70 % of one repetition maximum (1RM) with 1.5 min of rest interval between sets and exercises, three times a week. The HV group performed the same RT protocol as described for LV, except for the number of sets which was six (Fig. 2). Muscle strength (maximum leg extensor strength), anthropometric measures (skinfold, waist, and hip circumference), blood samples (metabolic and inflammatory indicators), and dietary intake (3-day food record) were measured at the beginning and at the end of the study (week 16). To avoid residual effects of training, all final measurements were performed 72 h after the last session of training.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of RT volume during 16 weeks. CT control group, LV low-volume group, and HV high-volume group. *Significant difference from week 1, p < 0.05; #Significant difference from week 4, p < 0.05

The women who dropped out or did not meet the compliance requirements were not retested, and an intention-to-treat analysis was not performed post hoc.

Anamnesis

Preliminarily, all volunteers were submitted to anamnesis to detect age, labor situation, indicators of health and history of past and present illnesses, medicinal and physical activities, and nutritional habits.

All women were submitted to a 3-day food record (2 days in the middle of week and 1 day on the weekend; Thompson and Byers 1994). Energy and macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) were quantified. Data were corrected for body weight to attenuate the interindividual differences. Data were calculated by a nutritionist, and the software “Dietpro” 5i version was used.

Anthropometric and body composition assessments

Body weight and height were measured with a digital scale (Lider®, Brazil) and a stadiometer fixed to the scale, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was classified according to the system used by the World Health Organization. Waist circumference (WC) and waist-hip ratio (WHR) were measured as an indicator of abdominal fat distribution. WC was assessed with an inelastic tape and was considered large when WC > 80 cm. WC was measured midway between the lowest rib margin and the iliac crest in the anatomical position. The measurement was taken at the end of a normal respiration, while subjects stood erect with arms hanging loosely at the sides and feet were together. The WHR was considered high when WHR > 0.85 (Bray and Ryan 2000).

The skinfolds were evaluated with the adipometer (Lange®) on the right side of the body and were carried out at four sites (biceps, triceps, subscapular, and supra-iliac). Three measurements were performed on each skinfold and the mean value was taken. Body density (BD) was determined by the equation proposed by Durnin and Womersley (1974), and the body fat percentage (F%) was determined by the equation proposed by Ortiz et al. (1992). Both equations were selected specifically for the population of this study.

Equations:

Maximum strength assessment and resistance training

One repetition maximum (1RM) test was performed to assess the maximum muscle strength in each exercise. Before 1RM test, all volunteers attended a 1-week familiarization period with low loads in order to learn the exercise techniques. After this week, three sessions in non-consecutive days of the 1RM test familiarization were performed, and afterward, the 1RM test was also performed. The load used as the maximum weight was the weight of the last exercise successfully performed (full range of motion) by the individual. Three to five attempts were used to determine the maximum load. The leg extension strength was used as an indicator of the muscle strength gain. An experienced examiner performed all 1RM measures.

A 3-day-a-week regimen of the RT protocol was performed during 16 weeks. All workouts were supervised by a qualified professional. The protocols followed the recommendations of the American College of Sports Medicine Guidelines for hypertrophy (American College of Sports 2009). No exercise other than RT was allowed. The protocol consisted of dynamic exercises for the upper and lower limbs. The exercises were squat, leg curl, leg extension, bench press, rowing machine, pull down, triceps pulley, and barbell curls.

HV and LV groups performed the RT protocol with 8–12 repetitions at 70 % 1RM. A warm-up (one set of 15 repetitions) with 40 % of 1RM was done in each exercise beforehand, and then, the LV group performed three sets and the HV six sets. The HV started the study with three sets and increased one set per week until they reached six sets and then kept on with that set amount for 12 weeks (Fig. 2). A resting period of 1.5 min was established between the sets and exercises. During the workout, the participants were advised to perform eccentric actions in 1 s and concentric actions in 1 s. During the training period, in the eighth week, the load was adjusted with the 1RM test to keep the relative load (70 % of 1RM; Fig. 2; American College of Sports et al. 2009).

Blood samples

Blood samples (16 ml) were collected between 7:30 AM and 9:00 AM after an overnight fast (10–12 h). The blood samples (venous) were collected by a dry tube with gel separator or EDTA (vacuum-sealed system; Vacutainer®, England). The sample was centrifuged for 10 min (3.000 rpm), and samples were separated and stocked (−20 °C) for futures analysis.

The blood indicators were measured by the respective methods, electrochemoluminescence (serum lipid profile), kinetic (serum estradiol (E2), FSH, T4, and TSH), automated colorimetric (plasma-glycated hemoglobin; Cobas 6000 equipment; Kit-Roche®, USA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (serum IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α; Readwell Touch equipment-Robonik®, India; Kits-DRG®, DRG International, USA, and R&D Systems®, Minneapolis, USA) methods.

Equations:

(Friedewald et al. 1972) was used to determine the low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol.

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The data are presented as median and interquartile range (P25–P75) or mean and standard deviation. Wilcoxon test was used to compare moments within groups. ANOVA repeated measure was solely used to compare RT volume. Kruskal-Wallis and post hoc rank were used to compare the groups at baseline and delta%. Spearman’s coefficient of rank correlation was used to associate variables. Effect sizes were measured by Cohen’s r (non-parametric data; r = Z/√N) to compare the efficiency of groups. Cohen’s effect sizes (r) were interpreted as follows: r < 0.1 = null effect, r < 0.3 = small effect, r < 0.5 = medium effect, and r ≥ 0.5 = large effect (Fritz et al. 2012). The significant level was set at 5 %.

Results

At first, the baseline clinical characteristics of all groups were interpreted and statistically compared. The E2 and FSH values were within the normal range for PW (Table 1). All participants showed excess weight and F%, large WC, high WHR, hypercholesterolemia, and borderline values to glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c%) altered (Tables 1, 3, and 4). The other clinical characteristics were within the normal range. There were no differences between groups for all baseline clinical characteristics, except for protein intake (Table 2) which was higher in HV group when compared to LV group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between groups

| CT (P25–P75) | LV (P25–P75) | HV (P25–P75) | p groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60.0 (54.0–64.5) | 62.0 (58.0–68.0) | 62.0 (54.7–65.5) | 0.283 |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 32.4 (25.2–33.6) | 27.8 (27.5–29.4) | 27.4 (23.3–33.7) | 0.647 |

| E2 (pg/ml) | 5.0 (5.0–10.4) | 5.0 (5.0–5.14) | 6.8 (5.0–12.1) | 0.635 |

| FSH (mUI/ml) | 62.0 (58.7–73.5) | 85.0 (60.1–115.4) | 79.9 (60.4–93.1) | 0.274 |

| T4 (ng/dl) | 1.0 (1.0–1.3) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 0.930 |

| TSH (mUI/L) | 2.8 (1.8–4.4) | 2.4 (1.0–2.8) | 3.2 (1.7–4.6) | 0.281 |

Data are presented in median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group, BMI body mass index, E 2 estradiol, FSH follicle-stimulating hormone, T4 free tiroxin, TSH thyroid-stimulating hormone

Table 3.

Biochemical characteristics between groups before and after 16 weeks of resistance training

| CT (P25–P75) | LV (P25–P75) | HV (P25–P75) | P baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | ||

| HbA1c% | 6.0 (5.6–6.2) | 5.7 (5.5–6.3) | 0.637 | 6.0 (5.8–6.1) | 5.6 (5.4–5.9) | 0.019 | 5.8 (5.6–6.1) | 5.9 (5.5–6.2) | 0.556 | 0.866 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 220.6 (197.4–242.2) | 209.5 (201.7–220.5) | 0.206 | 224.7 (208.1–265.5) | 231.3 (193.9–235.4) | 0.232 | 248.1 (231.9–256.4) | 228.9 (208.8–236.2) | 0.006 | 0.105 |

| HDL-c (mg/dl) | 63.0 (58.0–63.7) | 61.0 (57.5–66.5) | 0.965 | 67.0 (51.0–94.0) | 65.5 (55.0–92.0) | 0.322 | 58.0 (52.2–65.0) | 58.0 (54.5–65.7) | 0.764 | 0.347 |

| LDL-c (mg/dl) | 133.8 (112.6–157.6) | 127.2 (115.9–132.2) | 0.123 | 132.6 (114.1–169.6) | 124.8 (108.8–150.2) | 0.322 | 163.4 (147.1–174.9) | 139.8 (122.6–164.4) | 0.009 | 0.097 |

| VLDL-c (mg/dl) | 22.6 (15.8–32.6) | 21 (16.5–35.0) | 0.965 | 21.3 (13.6–35.6) | 19.7 (15.2–28.0) | 0.625 | 24.2 (21.1–27.6) | 23.2 (16.8–27.8) | 0.577 | 0.779 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 113.0 (79.0–163.0) | 105.0 (82.5–175.2) | 0.965 | 106.5 (68.0–178.0) | 98.5 (76.0–140.0) | 0.556 | 121.0 (105.7–138.2) | 116.0 (84.2–139.2) | 0.577 | 0.804 |

Data are presented in median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group, HbA1c% glycated hemoglobin, TC total cholesterol, HDL-c high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-c low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, VLDL-c very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides

Table 4.

Inflammatory and anthropometry characteristics between groups before and after 16 weeks of resistance training

| CT (P25–P75) | LV (P25–P75) | HV (P25–P75) | P baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markers | Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | |

| Inflammatory | ||||||||||

| IL-1 (pg/ml) | 0.6 (0.1–1.3) | 0.4 (0.2–1.4) | 0.570 | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.695 | 0.3 (0.1–0.3) | 0.1 (0.1–1.3) | 0.625 | 0.794 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 9.7 (1.9–13.2) | 12.6 (7.2–20.4) | 0.07 | 11.5 (9.7–19.3) | 14.1 (11.9–17.1) | 0.08 | 14.9 (11.9–15.6) | 14.5 (11.1–17.1) | 0.425 | 0.113 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 4.3 (1.9–6.2) | 3.8 (2.8–6.7) | 0.734 | 4.5 (3.4–5.2) | 5.0 (2.1–6.9) | 1.000 | 5.2 (4.1–6.1) | 4.3 (2.4–6.4) | 0.700 | 0.413 |

| Anthropometry | ||||||||||

| WC (cm) | 91.5 (87.0–101.2) | 95.5 (88.0–102.8) | 0.232 | 90.0 (87.5–91.5) | 90.2 (82.0–93.0) | 0.640 | 88.0 (79.5–94.1) | 84.0 (74.7–89.7) | 0.018 | 0.328 |

| WHR | 0.89 (0.85–0.94) | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) | 0.898 | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | 0.89 (0.86–0.94) | 0.496 | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) | 0.86 (0.78–0.87) | 0.001 | 0.942 |

| F% | 38.0 (35.8–39.4) | 37.3 (34.6–39.2) | 0.006 | 36.8 (35.4–39.1) | 33.7 (32.3–35.7) | 0.002 | 36.9 (33.8–41.4) | 32.7 (31.4–36.9) | 0.001 | 0.832 |

Data are presented in median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group, IL interleukin, TNF tumor necrosis factor, WC waist circumference, WHR waist circumference hip ratio, F% fat percentage

Table 2.

Dietary intake characteristics between groups before and after 16 weeks of resistance training

| CT (P25–P75) | LV (P25–P75) | HV (P25–P75) | P baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | Pre | Post | p | ||

| E (kcal/kg) | 26.0 (17.7–29.1) | 17.0 (13.8–21.7) | 0.08 | 21.5 (20.7–23.6) | 21.6 (19.8–32.2) | 1.000 | 30.7 (23.2–33.6) | 30.2 (23.3–35.4) | 0.278 | 0.194 |

| CHO (g/kg) | 3.9 (2.6–4.7) | 2.7 (2.2–3.3) | 0.06 | 3.3 (2.7–4) | 3.1 (3.0–4.4) | 1.000 | 4.1 (2.8–4.9) | 3.8 (2.8–5.5) | 0.519 | 0.596 |

| PTN (g/kg) | 1.1 (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.0) | 0.174 | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.769 | 1.5 (0.9–1.6)a | 1.1 (0.9–1.6) | 0.637 | 0.032 |

| LIP (g/kg) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | 0.898 | 0.5 (0.5–0.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | 0.845 | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.965 | 0.688 |

Data are presented in median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group, E energy intake, CHO carbohydrate intake, PTN protein intake, LIP lipid intake

aSignificant difference from LV group

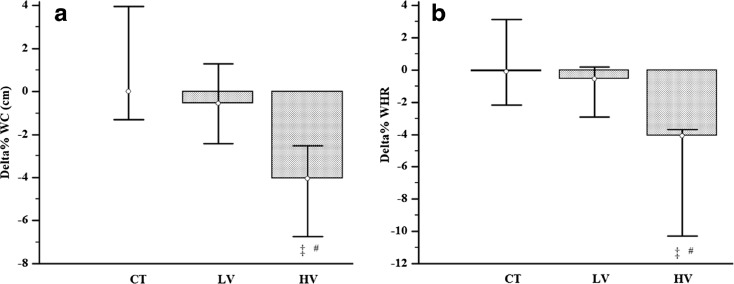

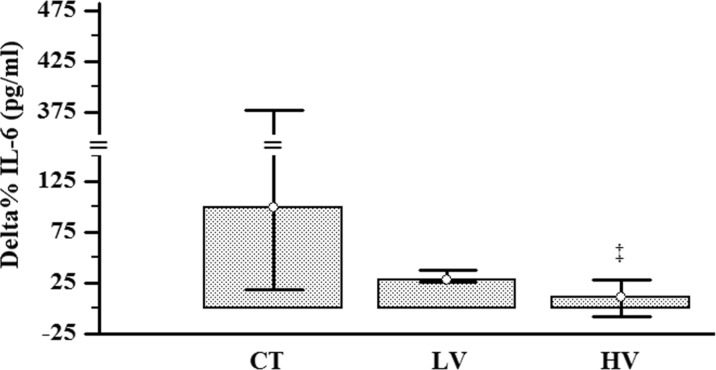

After that, the changes after 16 weeks of intervention (pre vs. post) and delta% of all groups were interpreted and statistically compared. There were no muscular and joint injuries to subjects. Both trained groups increased the 1RM performance in a similar way (effect size LV, r = −0.62; HV, r = −0.62; Table 5). The LV group reduced the HbA1c% (effect size r = 0.51), while the HV group reduced the total cholesterol (TC; effect size r = 0.55) and LDL-cholesterol (LDL-c; effect size r = 0.53; Table 3). All groups reduced F%; however, solely trained groups showed large effect size (effect size CT, r = −0.16; LV, r = −0.50; HV, r = −0.50). Only the HV group reduced the WC (effect size r = 0.49) and the WHR (effect size r = 0.62; Table 4 and Fig. 3). For the IL-6, there were no differences from baseline (pre vs. post) in all groups. However, when the IL-6 delta% were compared, the IL-6 delta% of HV group was lower than the delta% of the CT group (effect size r = −0.47; Fig. 4). The dietary intake, high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-c, very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-c, TG, IL-1, and TNF-α were unchanged after 16 weeks of RT (Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Table 5.

Strength characteristics between groups before and after 16 weeks of resistance training

| CT (P25–P75) | LV (P25–P75) | HV (P25–P75) | P baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leg extensor strength baseline (kg) | 70.0 (52.0–78.7) | 60.0 (55.0–75.0) | 62.0 (42.8–72.9) | 0.483 |

| Leg extensor strength 16th week (kg) | 74.0 (60.7–87.5) | 85.0* (75.0–102.0) | 80.0* (57.2–100.0) |

Data are presented in median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group

*Significant difference from baseline, p < 0.05

Fig. 3.

Delta% comparison of anthropometrics indicators of central fatness response between groups after 16 weeks of RT. WC (a) and WHR (b) response between groups after 16 weeks of RT. Delta difference between moments, CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group, WC waist circumference, and WHR waist circumference hip ratio. ‡Significant difference from CT group. #Significant difference from LV group, p < 0.05. The data are presented as median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

Fig. 4.

Delta% comparison of IL-6 response between groups after 16 weeks of RT. Delta difference between moments, CT control group, LV low-volume group, HV high-volume group. ‡Significant difference from CT group, p < 0.05. The data are presented as median and interquartile range (P25–P75)

The WHR delta% was positively correlated with IL-6 and WC deltas%. IL-6 and LDL-c were positively correlated with TC (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between delta% IL-6, TC, LDL-c, Hb1Ac, WHR, WC, and F% after 16 weeks of resistance training

| Delta% TC | Delta% LDL-c | Delta Hb1Ac% | Delta% WHR | Delta% WC | Delta F% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta% IL-6 | r = 0.43, P = 0.022 | r = 0.26, P = 0.168 | r = 0.10, P = 0.588 | r = 0.48, P = 0.010 | r = 0.21, P = 0.246 | r = 0.007, P = 0.971 |

| Delta% TC | r = 0.81, P = <0.001 | r = 0.10, P = 0.562 | r = 0.27, P = 0.122 | r = 0.13, P = 0.456 | r = −0.03, P = 0.830 | |

| Delta% LDL-c | r = −0.01, P = 0.948 | r = 0.14, P = 0.410 | r = −0.02, P = 0.890 | r = −0.05, P = 0.780 | ||

| Delta Hb1Ac% | r = −0.07, P = 0.694 | r = −0.02, P = 0.873 | r = 0.01, P = 0.936 | |||

| Delta% WHR | r = 0.72, P < 0.001 | r = 0.33, P = 0.066 | ||||

| Delta% WC | r = 0.24, P = 0.165 |

Delta% difference between moments, IL interleukin, TC total cholesterol, LDL-c low-density lipoprotein, Hb1Ac% glycated hemoglobin, WHR waist circumference hip ratio, WC waist circumference, and F% fat percentage

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare the effect of different RT volumes (three or six sets) on muscular strength and indicators of abdominal adiposity, metabolic risk, and inflammation in PW. The main findings were that while lower-volume RT improves HbA1c%, F%, and muscular strength, a higher-volume RT is necessary for improving TC, LDL-c, WC and WHR and also for preventing IL-6 increase in PW.

Abdominal obesity is an important metabolic risk factor and also an indicator of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in PW (Eguchi et al. 2012; Orsatti et al. 2010b; Petri Nahas et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2008). Therefore, identification of efficient interventions against obesity is necessary to PW. Thereby, exercises have shown to be an effective strategy against obesity. However, the exercise volume appears to play an important role in response magnitude of fat loss (Davidson et al. 2009; Friedenreich et al. 2015; Lera Orsatti et al. 2014; Slentz et al. 2011). This volume-response relationship has been well evidenced in moderate intensity aerobic exercise (Friedenreich et al. 2015). For instance, Friedenreich et al. (2015) showed that 5 days/week of moderate aerobic exercise for 60 min/session (300 min/week) are superior to 5 days/week for 30 min/session (150 min/week) for improving aerobic function and reducing total fat and other adiposity measures in PW (Friedenreich et al. 2015). Thereby, the reductions in body fat in PW appear be directly associated with either an enhancement of the muscle aerobic function (mitochondrial content; Kelley 2005; Wisloff et al. 2005) or (and) a higher-energy expenditure (Friedenreich et al. 2015; Nimmo et al. 2013). However, the role of RT volume on fat loss in PW is not clear. The RT protocol used to promote hypertrophy has shown modest to no effect on indicators of body fat and metabolic risk in PW (Brochu et al. 2009; Lera Orsatti et al. 2014; Maesta et al. 2007; Phillips et al. 2012; Senechal et al. 2012), and there are no studies that have used more than three sets on indicators of body fat and metabolic risk in PW. Studies using acute resistance exercise have shown that higher RT volume is associated with higher-energy expenditure (Haddock and Wilkin 2006; Phillips and Ziuraitis 2004) and with greater activation of signaling pathways that regulate PGC-1α (Ahtiainen et al. 2015; Combes et al. 2015). In the current study, even though the F% was reduced in both trained groups, solely, the higher-volume RT (six sets) reduced abdominal fat indicators (WC and WHR) in PW. Considering that a greater number of sets (volume/amount of exercise) was performed in HV group (Fig. 2) and the dietary intake did not change between groups (Table 2), a higher-volume RT seems to be necessary to reduce abdominal adiposity in PW.

Although WC and WHR are indirect measures of abdominal fat, it has been shown that they are highly correlated with the trunk fat measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Orsatti et al. 2010b) and abdominal visceral fat measured by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in older women (>40 years; Kamel et al. 2000; Pare et al. 2001; Rankinen et al. 1999; Ross et al. 1996). Moreover, changes in abdominal visceral fat measured by magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography during weight loss have been significantly correlated with the changes in WC and WHR in men and women (Kamel et al. 2000; Pare et al. 2001; Ross et al. 1996). Thus, WC and WHR are good predictors of abdominal visceral obesity.

High serum levels of inflammatory indicators (i.e., IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP)) have been associated with the development of metabolic syndrome, an important risk indicator of cardiovascular diseases and sarcopenia in PW (Ferrucci et al. 2002; Gallucci et al. 2007; Payette et al. 2003; Petri Nahas et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2008). In the current study, there was difference from baseline in all groups (Table 4). The CT showed medium effect sizes (r of 0.43), while the HV showed a small effect size (r of 0.19). The probability of superiority for medium effects such as r of 0.43 (CT) is ∼75 %. That is, if we sampled items randomly, one from each moment (pre- and post-intervention), the one from the post-intervention would be higher than the one from the pre-intervention for 75 % of the comparisons (Fritz et al. 2012). Moreover, the IL-6 delta% was significantly lower in HV group than in the CT group, and the effect size was an r of −0.47 (the probability of superiority for an r of 0.47 is ∼78 %; Fig. 4). The comparison of difference (delta%) between groups has been suggested the better approach in randomized controlled trial (Schulz et al. 2010). The reason for this comparison is that the intervention and control groups have similar changes over time in the absence of intervention. Thereby, the difference between intervention and control groups occurs because of what happens during the trial, not what happened anyway (Schulz et al. 2010). Thus, these data suggest that a higher-volume RT appears to be necessary for preventing IL-6 increase in PW. In a previous study, we have observed that higher RT frequency (3 vs. 1 day/week) prevented the rise of CRP (protein stimulated and produced in the liver by responding to pro-inflammatory cytokines) after 16 weeks of RT in sedentary and overweight PW (Lera Orsatti et al. 2014). Furthermore, the results from cross-sectional and prospective epidemiological studies suggest that a higher level of physical activity (kcal/week) results in reduced levels of inflammatory indicators (Geffken et al. 2001; Kasapis and Thompson 2005; Pischon et al. 2003). Although we did not perform energy expenditure measures, we speculate that energy expenditure was higher in the HV group than in LV groups (Phillips and Ziuraitis 2004). It is not clear how resistance training could influence the specific inflammatory activity. As solely, the HV group reduced WC and WHR and the delta% IL-6 was positively correlated with delta% WHR but not with F% (Table 6); our results suggest that a higher-volume RT is necessary to prevent an increased IL-6, mediated by abdominal fat reduction, in PW. Indeed, adipose tissue has been shown to be associated with pro-inflammatory cytokines (Coppack 2001). Furthermore, the abdominal visceral adipose tissue releases higher serum levels of IL-6 than the subcutaneous adipose tissue (Fried et al. 1998). However, in contrast to our results, Donges et al. (2010) reported that although both aerobic and resistance training decreased the abdominal and body fat, respectively, both training programs did not reduce IL-6 in sedentary subjects. Interestingly, the same study reported that only resistance exercise reduced CRP (Donges et al. 2010). Recently, opposite to Donges et al., Lee et al. (2015) reported that although both aerobic and resistance training did not decrease the WHR and body fat, both training programs reduced IL-6 in older women (Lee et al. 2015). Although the effects of RT in reducing IL-6 are not yet fully understood, it has been suggested that RT may modulate melanocortin 3 receptor expression, providing a possible mechanism for the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in post-menopausal women (Henagan et al. 2011). Moreover, it has also been suggested that these effects of RT on IL-6 may be mediated by modulation of anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-10, and soluble TNF-α receptors) produced at other sites, such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, and mononuclear cells (de Salles et al. 2010; Petersen and Pedersen 2005).

High levels of cholesterol have accounted for 4.5 % of total deaths per year (Organization 2009), and menopause contributes to an unfavorable lipid profile (Matthews et al. 1989). It has been shown that a reduction of 1 mmol/l (∼38.6 mg/dl) of TC reduces one third of the risk of mortality by cardiovascular disease in PW between 50 and 69 years (Collaboration 2007). In the present study, only the high-volume group reduced TC (∼19.2 mg/dl) and LDL-c (∼23.6 mg/dl). Thereby, higher-volume RT seems to benefit the cardiovascular system by reducing the TC and LDL-c in PW. Moreover, we observed an association between IL-6 delta% with TC delta% (Table 6), suggesting a possible mechanism in which higher-volume RT may influence cholesterol reduction. Indeed, inflammation has been reported to increase the lipid profile due to the increase of hepatic cholesterol synthesis and total HMG-CoA reductase activity (Feingold et al. 1993; Memon et al. 1993).

RT has been well reported to improve insulin action (Willey and Singh 2003) and glycemic control (Sigal et al. 2007). However, these effects may be diminished in sedentary women following acute exercise that induces muscle damage (Jamurtas et al. 2013), such as high-volume RT. Roth et al. showed that older women exhibit higher levels of muscle damage after high-volume RT than young women do (Roth et al. 2000). In the present study, solely, the LV group reduced HbA1c%; however, the HV group’s HbA1c% was not worsened (Table 3). Therefore, low-volume RT seems to be more beneficial for lowering HbA1c% than high-volume RT, but the high-volume RT is safe for PW with respect to HbA1c%.

Lowered muscle strength is an important determinant of impaired functional capacity among PW. Impaired functional capacity has been associated with an increased risk of falls, increased mobility disability, and osteoporotic fractures (Legrand et al. 2014; Rantanen 2003; Sirola and Rikkonen 2005). In the present study, we observed that the muscle strength increased with RT, regardless of RT volume (Tables 5 and 6). These findings suggest that a high volume (>three sets) is not necessary to promote additional strength gains in PW over LV. However, three sets have been reported to be better than one set to promote strength gains in older people (Alex et al. 2015; Galvao and Taaffe 2005; Radaelli et al. 2014). Following this viewpoint, this information suggests that three sets could be a possible volume threshold to strength gains in PW. Studies in young people have provided evidence of a possible volume threshold and that additional volume provides no further benefits in muscle strength (Gonzalez-Badillo et al. 2005; Gonzalez-Badillo et al. 2006; Martin-Hernandez et al. 2013), corroborating with this hypothesis.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that while low-volume RT improves HbA1c%, muscular strength, and F%, high-volume RT is necessary to reduce WC, WHR, TC, and LDL-c and also prevent IL-6 increase in PW. Therefore, PW who need to decrease anthropometric indicators of abdominal adiposity and improve lipid metabolism and inflammation would benefit from a progression of RT with volume ranging from three to six sets, whereas for HbA1c%, F%, and muscular strength improvements, the traditional volume RT (three sets) would suffice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Camila Botelho Miguel and Luanna Margato for assisting us with the subjects. This investigation was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do estado de Minas Gerais–FAPEMIG, by Fundação de Ensino e Pesquisa de Uberaba–FUNEPU, and by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–CAPES.

References

- Ahtiainen JP, et al. Exercise type and volume alter signaling pathways regulating skeletal muscle glucose uptake and protein synthesis. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115:1835–1845. doi: 10.1007/s00421-015-3155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alex S, Ribeiro BJS, Fábio L, Pina C, Souza MF, Matheus A, Nascimento, dos Santos L, Antunes M, Cyrino ES. Resistance training in older women: comparison of single vs. multiple sets on muscle strength and body composition. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 2015;23:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports M American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Progression models in resistance training for healthy adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2009;41:687–708. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181915670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Sports M et al American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1510–1530. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181a0c95c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AP, Schulman H. The multifunctional calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase: from form to function. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57:417–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray GA, Ryan DH. Clinical evaluation of the overweight patient. Endocrine. 2000;13:167–186. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:13:2:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brochu M, et al. Resistance training does not contribute to improving the metabolic profile after a 6-month weight loss program in overweight and obese postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3226–3233. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaboration PS Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–1839. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61778-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes A, Dekerle J, Webborn N, Watt P, Bougault V, Daussin FN (2015) Exercise-induced metabolic fluctuations influence AMPK, p38-MAPK and CaMKII phosphorylation in human skeletal muscle. Physiological reports 3 doi:10.14814/phy2.12462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coppack SW. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and adipose tissue. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60:349–356. doi: 10.1079/PNS2001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LE, et al. Effects of exercise modality on insulin resistance and functional limitation in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:122–131. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Salles BF, Simao R, Fleck SJ, Dias I, Kraemer-Aguiar LG, Bouskela E. Effects of resistance training on cytokines. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:441–450. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1251994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donges CE, Duffield R, Drinkwater EJ. Effects of resistance or aerobic exercise training on interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and body composition. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:304–313. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b117ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durnin JVGA, Womersley JVGA (1974) Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr 32(1):77–97 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eguchi Y, et al. Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2009 to 2010 in Japan: a multicenter large retrospective study. J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:586–595. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0533-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold KR, Hardardottir I, Memon R, Krul E, Moser A, Taylor J, Grunfeld C. Effect of endotoxin on cholesterol biosynthesis and distribution in serum lipoproteins in Syrian hamsters. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:2147–2158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, et al. Change in muscle strength explains accelerated decline of physical function in older women with high interleukin-6 serum levels. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1947–1954. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried SK, Bunkin DA, Greenberg AS. Omental and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese subjects release interleukin-6: depot difference and regulation by glucocorticoid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:847–850. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenreich CM, et al. Effects of a high vs moderate volume of aerobic exercise on adiposity outcomes in postmenopausal women: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. Oncology. 2015;1:766–776. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2–18. doi: 10.1037/a0024338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci M, et al. Associations of the plasma interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels with disability and mortality in the elderly in the Treviso Longeva (Trelong) study. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 44. Suppl. 2007;1:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao DA, Taaffe DR. Resistance exercise dosage in older adults: single-versus multiset effects on physical performance and body composition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:2090–2097. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber CE, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–1359. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geffken DF, Cushman M, Burke GL, Polak JF, Sakkinen PA, Tracy RP. Association between physical activity and markers of inflammation in a healthy elderly population. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:242–250. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Badillo JJ, Gorostiaga EM, Arellano R, Izquierdo M. Moderate resistance training volume produces more favorable strength gains than high or low volumes during a short-term training cycle. J Strength Cond Res Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2005;19:689–697. doi: 10.1519/R-15574.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Badillo JJ, Izquierdo M, Gorostiaga EM. Moderate volume of high relative training intensity produces greater strength gains compared with low and high volumes in competitive weightlifters. J Strength Cond Res Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2006;20:73–81. doi: 10.1519/R-16284.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddock BL, Wilkin LD. Resistance training volume and post exercise energy expenditure. Int J Sports Med. 2006;27:143–148. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartz A, He T, Rimm A. Comparison of adiposity measures as risk factors in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:227–233. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henagan TM, Phillips MD, Cheek DJ, Kirk KM, Barbee JJ, Stewart LK. The melanocortin 3 receptor: a novel mediator of exercise-induced inflammation reduction in postmenopausal women? J Aging Res. 2011;2011:512593. doi: 10.4061/2011/512593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamurtas AZ, et al. A single bout of downhill running transiently increases HOMA-IR without altering adipokine response in healthy adult women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:2925–2932. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel EG, McNeill G, Van Wijk MC. Change in intra-abdominal adipose tissue volume during weight loss in obese men and women: correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and anthropometric measurements. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:607–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamel HK, Maas D, EH D. Role of hormones in the pathogenesis and management of sarcopenia. Drugs Aging. 2002;19:865–877. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200219110-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasapis C, Thompson PD. The effects of physical activity on serum C-reactive protein and inflammatory markers: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1563–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley DE. Skeletal muscle fat oxidation: timing and flexibility are everything. J Clin Investig. 2005;115:1699. doi: 10.1172/JCI25758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan K, et al. Associations between weight in early adulthood, change in weight, and breast cancer risk in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22:1409–1416. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Kim CG, Seo TB, Kim HG, Yoon SJ. Effects of 8-week combined training on body composition, isokinetic strength, and cardiovascular disease risk factors in older women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2015;27:179–186. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand D, Vaes B, Mathei C, Adriaensen W, Van Pottelbergh G, Degryse JM. Muscle strength and physical performance as predictors of mortality, hospitalization, and disability in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jgs.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lera Orsatti F, Nahas EA, Maesta N, Nahas Neto J, Lera Orsatti C, Vannucchi Portari G, Burini RC. Effects of resistance training frequency on body composition and metabolics and inflammatory markers in overweight postmenopausal women. J Sports Med Physical fitness. 2014;54:317–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maesta N, Nahas EA, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti FL, Fernandes CE, Traiman P, Burini RC. Effects of soy protein and resistance exercise on body composition and blood lipids in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2007;56:350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Hernandez J, Marin PJ, Menendez H, Ferrero C, Loenneke JP, Herrero AJ. Muscular adaptations after two different volumes of blood flow-restricted training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:e114–e120. doi: 10.1111/sms.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Meilahn E, Kuller LH, Kelsey SF, Caggiula AW, Wing RR. Menopause and risk factors for coronary heart disease. New Engl J Med. 1989;321:641–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memon RA, Grunfeld C, Moser AH, Feingold KR. Tumor necrosis factor mediates the effects of endotoxin on cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism in mice. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2246–2253. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8477669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmo MA, Leggate M, Viana JL, King JA. The effect of physical activity on mediators of inflammation Diabetes Obes Metab 15. Suppl. 2013;3:51–60. doi: 10.1111/dom.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization WH (2009) Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. World Health Organization

- Orsatti FL, Nahas EA, Nahas-Neto J, Maesta N, Orsatti CL, Fernandes CE. Effects of resistance training and soy isoflavone on body composition in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2010;2010:156037. doi: 10.1155/2010/156037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsatti FL, Nahas EA, Nahas-Neto J, Maesta N, Orsatti CL, Vespoli Hde L, Traiman P. Association between anthropometric indicators of body fat and metabolic risk markers in post-menopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol Off J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:16–22. doi: 10.3109/09513590903184076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz O, Russell M, Daley TL, Baumgartner RN, Waki M, Lichtman S, Wang J, Pierson RN Jr, Heymsfield SB (1992) Differences in skeletal muscle and bone mineral mass between black and white females and their relevance to estimates of body composition. Am J Clin Nutr 55(1):8–13 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pare A, et al. Is the relationship between adipose tissue and waist girth altered by weight loss in obese men? Obes Res. 2001;9:526–534. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payette H, Roubenoff R, Jacques PF, Dinarello CA, Wilson PW, Abad LW, Harris T. Insulin-like growth factor-1 and interleukin 6 predict sarcopenia in very old community-living men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1237–1243. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AM, Pedersen BK. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1154–1162. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00164.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petri Nahas EA, Padoani NP, Nahas-Neto J, Orsatti FL, Tardivo AP, Dias R. Metabolic syndrome and its associated risk factors in Brazilian postmenopausal women. Climacteric: the journal of the International Menopause. Society. 2009;12:431–438. doi: 10.1080/13697130902718168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeilschifter J, Koditz R, Pfohl M, Schatz H. Changes in proinflammatory cytokine activity after menopause. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:90–119. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.1.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips MD, Patrizi RM, Cheek DJ, Wooten JS, Barbee JJ, Mitchell JB. Resistance training reduces subclinical inflammation in obese, postmenopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2099–2110. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182644984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips WT, Ziuraitis JR. Energy cost of single-set resistance training in older adults. J Strength Cond Res Natl Strength Cond Assoc. 2004;18:606–609. doi: 10.1519/1533-4287(2004)18<606:ECOSRT>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischon T, Hankinson SE, Hotamisligil GS, Rifai N, Rimm EB. Leisure-time physical activity and reduced plasma levels of obesity-related inflammatory markers. Obes Res. 2003;11:1055–1064. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli R, et al. Time course of low-and high-volume strength training on neuromuscular adaptations and muscle quality in older women. Age. 2014;36:881–892. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9611-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankinen T, Kim SY, Perusse L, Despres JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:801–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T. Muscle strength, disability and mortality. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:3–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross R, Rissanen J, Hudson R. Sensitivity associated with the identification of visceral adipose tissue levels using waist circumference in men and women: effects of weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth SM, Martel GF, Ivey FM, Lemmer JT, Metter EJ, Hurley BF, Rogers MA. High-volume, heavy-resistance strength training and muscle damage in young and older women. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(3):1112–1118. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.3.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senechal M, Bouchard DR, Dionne IJ, Brochu M. The effects of lifestyle interventions in dynapenic-obese postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:1015–1021. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318248f50f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigal RJ, et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:357–369. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirola J, Rikkonen T. Muscle performance after the menopause. J Br Menopause Soc. 2005;11:45–50. doi: 10.1258/136218005775544561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slentz CA, et al. Effects of aerobic vs. resistance training on visceral and liver fat stores, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance by HOMA in overweight adults from STRRIDE AT/RT American journal of physiology. Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E1033–E1039. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00291.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson FE, Byers T. Dietary assessment resource manual. J Nutr. 1994;124:2245s–2317s. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.suppl_11.2245s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth MJ, Tchernof A, Sites CK, Poehlman ET. Effect of menopausal status on body composition and abdominal fat distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:226–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willey KA, Singh MA. Battling insulin resistance in elderly obese people with type 2 diabetes: bring on the heavy weights. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1580–1588. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisloff U, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors emerge after artificial selection for low aerobic capacity. Science. 2005;307:418–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1108177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, Rexrode KM, van Dam RM, Li TY, Hu FB. Abdominal obesity and the risk of all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: sixteen years of follow-up in US women. Circulation. 2008;117:1658–1667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]