Abstract

Age-related changes in motor unit activation properties remain unclear for locomotor muscles such as quadriceps muscles, although these muscles are preferentially atrophied with aging and play important roles in daily living movements. The present study investigated and compared detailed motor unit firing characteristics for the vastus lateralis muscle during isometric contraction at low to moderate force levels in the elderly and young. Fourteen healthy elderly men and 15 healthy young men performed isometric ramp-up contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contractions (MVC) during knee extension. Multichannel surface electromyograms were recorded from the vastus lateralis muscle using a two-dimensional grid of 64 electrodes and decomposed with the convolution kernel compensation technique to extract individual motor units. Motor unit firing rates in the young were significantly higher (~+29.7 %) than in the elderly (p < 0.05). There were significant differences in firing rates among motor units with different recruitment thresholds at each force level in the young (p < 0.05) but not in the elderly (p > 0.05). Firing rates at 60 % of the MVC force level for the motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC were significantly correlated with MVC force in the elderly (r = 0.885, p < 0.0001) but not in the young (r = 0.127, p > 0.05). These results suggest that the motor unit firing rate in the vastus lateralis muscle is affected by aging and muscle strength in the elderly and/or age-related strength loss is related to motor unit firing/recruitment properties.

Keywords: Aging, Multichannel surface electromyography, Quadriceps femoris muscles

Introduction

The decrease in muscle strength with aging cannot be explained solely by a decrease in the muscle volume: age-related strength and muscle mass declines are 2.5~4.0 and 0.5~1.0 % per year, respectively, and age-related strength decline is 2~5 times greater than age-related muscle volume decline (Mitchell et al. 2012). This suggests that in addition to morphological changes, other factors strongly contribute to the decline in muscle strength in the elderly. Voluntary force production in the skeletal muscle is modulated by the number of motor units recruited and their firing behavior. Thus, motor unit activation properties and other neural factors are important to better understand and determine the muscle strength of the elderly and its decline with aging (Roos et al. 1997).

Age-related changes in motor unit behavior have been investigated mainly for the small hand muscles (Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Knight and Kamen 2007; Nelson et al. 1983, 1984; Patten et al. 2001; Soderberg et al. 1991). From these studies, there has been a gradual accumulation of knowledge about the effects of aging on motor unit firing characteristics, such as a decrease in the firing rate. On the other hand, insufficient research has been conducted in the field of motor unit behavior in the elderly for locomotor muscles such as the quadriceps femoris muscles (Knight and Kamen 2008; Piasecki et al. 2015; Roos et al. 1999; Welsh et al. 2007). It is well known that quadriceps femoris muscles play important roles in standing, walking, and other daily living movements and this muscle group is highly susceptible to age-related muscle atrophy (Abe et al. 2014, 2011b). Roos et al. (1999) compared motor unit firing rates in the young and elderly in the vastus medialis muscle and found no significant differences between the groups (Roos et al. 1999). Their results were not in agreement with the other studies on small hand muscles (Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Knight and Kamen 2007; Nelson et al. 1983, 1984; Patten et al. 2001; Soderberg et al. 1991). Other studies also compared motor unit firing characteristics in the quadriceps femoris muscles, i.e., vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris muscles, between the young and elderly (Piasecki et al. 2015; Welsh et al. 2007). While detailed motor unit firing properties were not reported in these studies since they focused on other neuromuscular variables, they revealed a lower firing rate in the elderly compared with the young (Piasecki et al. 2015; Welsh et al. 2007). Also, these studies calculated the motor unit firing rate from all recruited motor units at a specific force level, although it is known that firing rate behaviors are inconsistent among motor units with different recruitment thresholds (De Luca and Hostage 2010, 1982; Erim et al. 1996; Oya et al. 2009). Therefore, firing rates of motor units should be evaluated for individual motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds in order to investigate the detailed motor unit activation properties.

In previous studies, motor unit firing properties were recorded with the intramuscular electromyography (EMG) technique (Christie and Kamen 2010; Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Knight and Kamen 2007; Nelson et al. 1983, 1984; Patten et al. 2001; Soderberg et al. 1991). While this technique enables the direct detection of motor unit firings, it is invasive. Also, because the detectable number of motor units is very small, the insertion of needle or wire electrodes should be repeated in order to detect a sufficient number of motor units. This causes considerable discomfort to the investigated subjects. In recent years, there have been several attempts to identify detailed motor unit firing characteristics noninvasively using multichannel surface EMG (SEMG) (Farina and Enoka 2011; Farina et al. 2004; Holobar et al. 2009, 2012; Holobar and Zazula 2004, 2008; Merletti et al. 2008; Watanabe et al. 2013). This technique is useful when the insertion of needle or wire electrodes is not desirable or possible. Moreover, multichannel SEMG employing 64–128 surface electrodes increases the number of detectable motor units when compared with intramuscular EMG. This methodological advantage allows us to investigate detailed motor unit firing characteristics, such as the relationships of firing rates among the motor units with different recruitment thresholds.

The purpose of this study was to compare the detailed firing properties of individual motor units with a different recruitment threshold in the vastus lateralis muscle during force production at low to moderate force levels between the elderly and young subjects. Also, we investigated the relationship between the motor unit firing rate and maximal muscle strength. We hypothesized that in the elderly, the firing rate of individual motor units is lower than that in the young; similarly to other muscles (Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Nelson et al. 1984; Patten et al. 2001; Soderberg et al. 1991), firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units are higher than those of later-recruited motor units at any time and force (De Luca and Hostage 2010; De Luca et al. 1982; Erim et al. 1996), and motor unit firing behavior is associated with maximal muscle strength. Since it was reported that the change in the motor unit firing rate during resistance training was greater in the elderly than the young (Christie and Kamen 2010; Patten et al. 2001), motor unit firing rate may be more adaptable and variable in the elderly.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Fourteen healthy elderly men (age 71.1 ± 5.6 years) and 15 healthy young men (age 20.6 ± 1.1 years) participated in this study (Table 1). The subjects in both groups gave written informed consent for the study after receiving a detailed explanation of the purposes, potential benefits, and risks associated with participation. All procedures used in this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Chukyo University (2014-001) and were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the elderly and young subjects

| Elderly (n = 14) | Young (n = 15) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70.3 ± 7.1* | 20.6 ± 1.1 |

| Height (cm) | 166.0 ± 6.1* | 172.7 ± 6.6 |

| Body mass (kg) | 62.6 ± 7.7 | 62.8 ± 5.3 |

| MVC (Nm) | 107.8 ± 29.4* | 160.6 ± 23.9 |

| MVC/body mass (Nm/kg) | 1.7 ± 0.4* | 2.6 ± 0.4 |

| Subcutaneous tissue thickness (cm) | 0.55 ± 0.15 | 0.46 ± 0.18 |

| Muscle thickness (cm) | 2.02 ± 0.32* | 2.36 ± 0.31 |

Data are reported as mean ± SD

*p < 0.05 vs. young

Experimental design

All subjects came to the laboratory 1 day~1 week before the experimental day to familiarize themselves with the motor tasks used in the present study.

During the experiment, the subjects were seated comfortably, with the right leg fixed in a custom-made dynamometer with a force transducer (LU-100KSE; Kyowa Electronic Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) and with both hip and knee joint angles flexed at 90° (180° corresponds to full extension). Subjects performed maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) and ramp contraction to low and moderate force levels during isometric knee extension.

The MVC was determined according to our previously reported procedures (Watanabe and Akima 2011; Watanabe et al. 2012a, b). Briefly, the subjects were asked to gradually increase their knee extension force from the baseline to maximum in 2–3 s and then sustain it maximally for 2 s. The timing of the task was based on a verbal count given at 1-s intervals, with vigorous encouragement from the investigators when the force began to plateau. The subjects performed at least two MVC trials with ≥2 min rest in between. The highest MVC force was used to calculate MVC torque and target torque for sustained contraction. The reliability of MVC measurement was validated by calculation of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). ICC for two MVC trials was high enough to be determined as MVC, i.e., 0.963 for the elderly and 0.974 for the young. The knee extension torque was calculated as the product of the knee extension force and distance between the estimated rotation axes for the knee joint in the sagittal plane. The force transducer was located approximately 10 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus on the front of the shank.

After the MVC recording, the subjects performed ramp contractions at two different force levels, i.e., from 0 to 30 % MVC in 15 s and 0 to 70 % MVC in 35 s (rate of force increase 5 % MVC/s). Target and performed forces were shown to the subjects on a monitor. The distance between the subject’s face and the monitor was approximately 60 cm. For ramp contraction from 0 to −30 % of MVC, subjects were instructed to sustain 30 % of MVC for 15 s after reaching it. This sustained phase was used for tracking motor units with a high accuracy in decomposition analysis. In 70 % MVC ramp contractions, this constant force phase was skipped in order not to avoid fatiguing the muscle. In each ramp contraction with a different target force, two trials were performed with a >2-min rest period in between. Out of these trials, the one trial with the smaller error between the targeted and performed forces was selected for analysis.

EMG recording

Multichannel SEMG signals were recorded from the vastus lateralis (VL) muscle with a semi-disposable adhesive grid of 64 electrodes (ELSCH064R3S, OT Bioelectronica, Torino, Italy) using the same procedure as in our previous study (Watanabe et al. 2013, 2012a, b). The grid is comprised of 13 rows and 5 columns of electrodes (1-mm diameter, 8-mm inter-electrode distance in both directions) with 1 missing electrode in the upper left corner. Prior to attaching the electrode grid, the skin was cleaned with alcohol. The longitudinal axis of the VL muscle was identified along the line between the head of the great trochanter and inferior lateral edge of the patella; the distance between these two anatomical reference points was used as the muscle length. The mid-point of the longitudinal axis of the VL muscle was measured and marked on the skin. Before grid positioning, longitudinal ultrasonographic images (SSD-900, ALOKA, Tokyo, Japan) were taken in correspondence with the marked point, to determine the thickness of the subcutaneous tissue and VL muscle. The electrode grid was placed with its center on the marked position and the columns aligned with the VL longitudinal axis. The position of the missing electrode was located proximally. Conductive gel was inserted into the cavities of the grid electrode to assure proper electrode contact with the skin. The grid electrode was connected to the amplifier through four connectors which were fixed to the skin by elastic tape. A reference electrode (C-150, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) was placed at the iliac crest.

Monopolar SEMG signals were detected and amplified by a factor of 1000, sampled at 2048 Hz, and converted to digital form by a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (EMG-USB, OT Bioelectronica, Torino, Italy) together with the force transducer signal. Recorded monopolar SEMG signals were off-line band-pass filtered (10–500 Hz) and transferred into analysis software (MATLAB R2009b, MathWorks GK, Tokyo, Japan). Fifty-nine bipolar SEMG signals were calculated, from the 64 monopolar signals along the electrode grid columns.

Signal analysis

Recorded EMG signals were decomposed with the Convolution Kernel Compensation (CKC) technique (Holobar et al. 2009; Holobar and Zazula 2004, 2008; Merletti et al. 2008) (Fig. 1). This decomposition technique has been validated extensively with both simulated and experimental signals, and the detailed analytical procedure was described (Farina et al. 2010; Gallego et al. 2015a, b; Holobar et al. 2009; Yavuz et al. 2015) and applied in many previous studies (Holobar et al. 2012; Minetto et al. 2009; Minetto et al. 2011; Watanabe et al. 2013). The pulse-to-noise ratio (PNR), introduced by Holobar et al. (2014), was used as a reliable indicator of motor unit identification accuracy (Holobar et al. 2014). Only motor units with PNR > 30 dB (corresponding to the accuracy of motor unit firing identification >90 %) were used for further analysis whereas all the other motor units were discarded (Holobar et al. 2014). Identified motor units were manually verified on visual inspection by one investigator, and the results were checked by another investigator. After the decomposition, instantaneous firing rates of individual identified motor units were calculated from the discharge times. Inter-discharge intervals <33.3 or >250 ms were excluded from the calculation of the firing rate, since they lead to an unusually high (>30 Hz) or low (<4 Hz) instantaneous firing rate. This range of the unusual firing rate was set according to previous studies that used the same muscle (Adam and de Luca 2005; Holobar et al. 2009; Watanabe et al. 2013; Welsh et al. 2007).

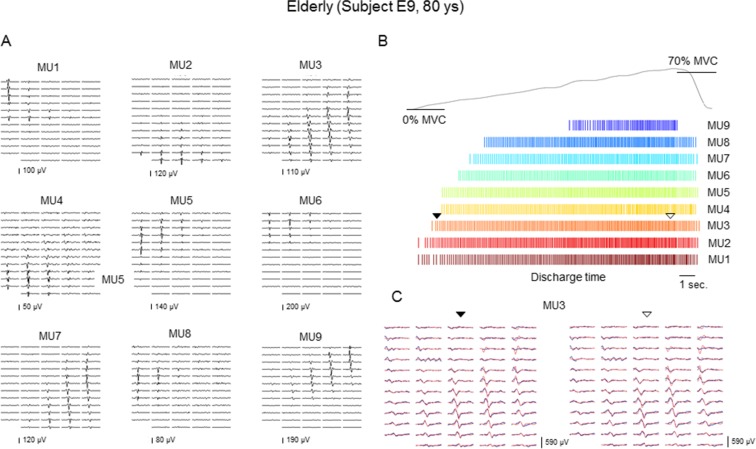

Fig. 1.

Representation of the multichannel SEMG decomposition in an elderly (80 years old) subject during ramp contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). a Motor unit action potential (MUAP) templates of 9 motor units, identified by the Convolution Kernel Compensation (CKC) technique from a multichannel surface electromyogram. b Discharge patterns of the detected individual motor units and performed force. c MUAP template (red line) and actual MUAP (blue line) of MU3 at around recruitment (filled inverted triangle) and peak firing (open inverted triangle)

Mean firing rates of individual motor units were calculated from instantaneous firing rates during each 5 % of MVC, e.g., the mean firing rate at 20 % of MVC was calculated from instantaneous firing rates during 17.5–22.5 % of MVC, for both ramp contractions to 30 and 70 % of MVC. Mean firing rates with >30 % coefficient of variation were excluded for further analysis (Fuglevand et al. 1993). Detected motor units were divided into four and three groups by the recruitment force: motor units recruited at <10, 10–15, 15–20, and 20–25 % of MVC for ramp contraction to 30 % of MVC and <20, 20–40, and 40–60 % of MVC for ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC. These four and three motor unit groups were used for further analyses.

For the motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC during ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC, the slopes of the firing rate with regard to the force (% of MVC) were calculated using simple linear regression lines in order to quantify the relationship between the firing rate and increase in the force level.

Statistics

All data are provided as the mean and SD. The age, height, body mass, MVC torque, MVC torque relative to body mass, thickness of subcutaneous tissue and VL muscle, mean firing rate of each motor unit group at each force level, and slope of the firing rate for individual motor unit groups during ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC were compared between elderly and young groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. The mean firing rate of a motor unit group at a specific force level was compared with that at the next force level by the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to identify changes in the firing rate with the force. At each force level, firing rates were compared among motor unit groups that were recruited at different force levels within the elderly or young group using the Mann-Whitney U test when a significant effect of the recruitment thresholds was identified by the Kruskal-Wallis test. For ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated among the mean firing rate at 60 % of MVC, mean slope of firing rates for motor unit groups recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively, and MVC torque in each group. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 15.0, SPSS, Tokyo, Japan) and MATLAB (R2009b, MathWorks GK, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

There were significant differences (p < 0.05) in age, height, MVC, MVC/body mass, and muscle thickness between the elderly and young groups (Table 1).

During ramp contractions to 30 and 70 % of MVC, 154 and 131 motor units for elderly subjects and 146 and 114 motor units for young subjects were considered for analysis, respectively (Table 2). For ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC, motor unit firing in some subjects and/or some motor units were not detected with the required accuracy (PNR > 30 dB) at forces exceeding 65 % of MVC. We thus analyzed firing rates of motor units up to 60 % of MVC.

Table 2.

Number of motor units considered for analysis

| Elderly | Young | |

|---|---|---|

| Ramp contraction 0~30 % MVC (total) | 154 | 146 |

| Motor units recruited at <10 % MVC | 43 | 32 |

| Motor units recruited at 10–15 % MVC | 38 | 45 |

| Motor units recruited at 15–20 % MVC | 44 | 40 |

| Motor units recruited at 20–25 % MVC | 29 | 29 |

| Ramp contraction 0~70 % MVC (total) | 131 | 114 |

| Motor units recruited at <20 % MVC | 69 | 41 |

| Motor units recruited at 20–40 % MVC | 51 | 59 |

| Motor units recruited at 40–60 % MVC | 11 | 14 |

Ramp contraction at 0~30 % of MVC

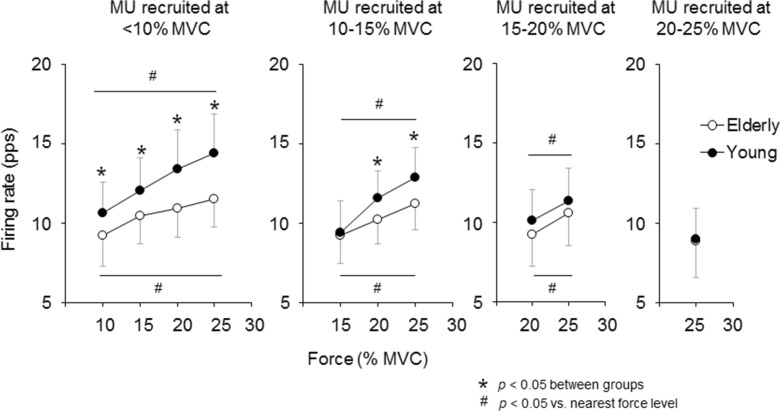

In both the elderly and young groups, firing rates of motor units recruited at <10, 10–15, and 15–20 % of MVC were significantly increased (p < 0.05) with an increase in the force level (Fig. 2). In young subjects, firing rates of motor units recruited at <10 % of MVC were significantly higher (~+14.6 %, p < 0.05) than in those of elderly subjects at 10, 15, 20, and 25 % of MVC (Fig. 2). Also, at 20 and 25 % of MVC, firing rates of motor units recruited at 10–15 % of MVC were significantly higher in young subjects (~+9.7 %, p < 0.05) than in elderly subjects (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mean firing rates among individual motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds between the elderly and young subjects during ramp contraction to 30 % of the maximal voluntary contraction. The open and closed circles represent the elderly and young groups, respectively. The marks asterisk and number sign indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups and between force levels, respectively

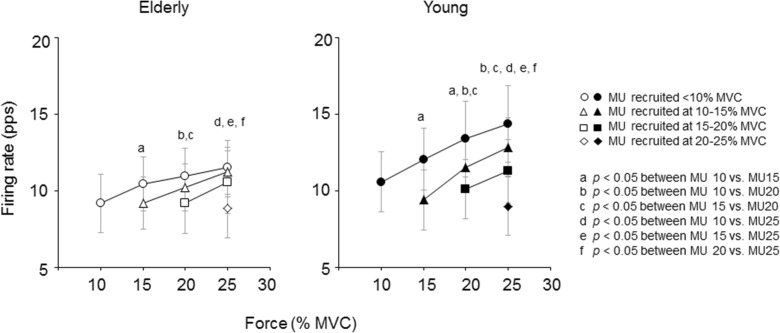

In the elderly group, firing rates of newly recruited motor units were significantly lower than those of earlier-recruited motor units, i.e., when measured at the same force level, the firing rates of motor units recruited at 10–15, 15–20, and 20–25 % of MVC were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than those of motor units recruited at <10, < 15, and <20 % of MVC, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of mean firing rates among individual motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds for the elderly and young groups during the ramp contraction to 30 % of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). The circles, triangles, squares, and diamonds indicate motor units (MU) recruited at <10, 10–15, 15–20, and 20–25 % of MVC, respectively. Letters a, b, c, d, e, and f indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) at 10 vs. 15 %, 10 vs. 20 %, 15 vs. 20 %, 10 vs. 25 %, 15 vs. 25 %, and 20 vs. 25 % of MVC, respectively

Similarly to the elderly group, when measured at the same force levels, firing rates of newly recruited motor units in the young group were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than those of earlier-recruited motor units (Fig. 3). Also, significant differences were found in the firing rates among motor units recruited at different force levels even after their recruitment. For example, at 20 % of MVC, significant differences were observed not only between motor units recruited at 15–20 % of MVC and other force levels but also between motor units recruited at <10 and 10–15 % of MVC (Fig. 3).

Ramp contraction at 0~70 % of MVC

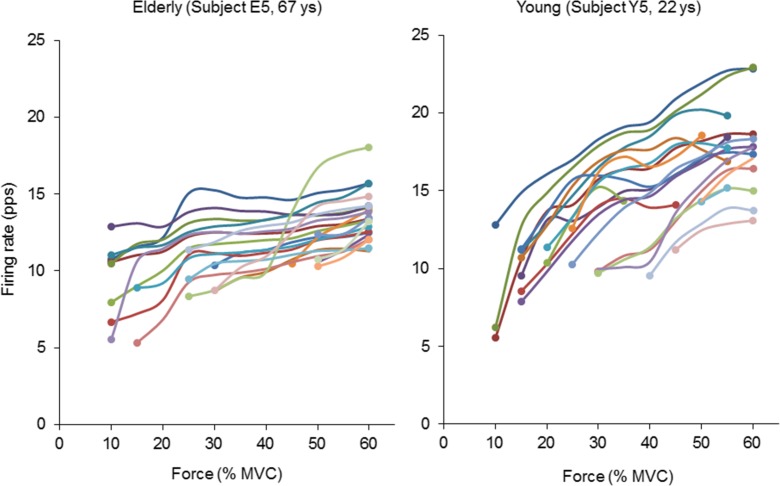

Figure 4 displays the representative motor unit firing rates for elderly and young subjects. While firing rates of individual motor units increased with the force level in both groups of subjects, the increase in the motor unit firing rate was less prominent in the elderly than in the young subjects. Also, firing rates of individual motor units with different recruitment thresholds change hierarchically with an increase in the force level in the young but not in the elderly subjects (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Firing rates of individual motor units in a representative elderly (67 years old) and young (22 years old) subject during ramp contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contraction. Firing rates were calculated for each 5 % increase in force

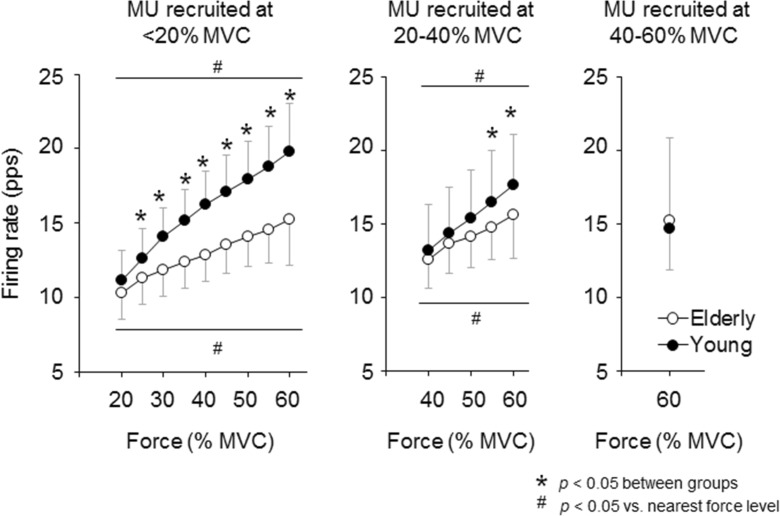

In both the elderly and young groups, firing rates of motor units recruited at <20, 20–40, and 40–60 % of MVC were significantly increased (p < 0.05) with an increase in the force level (Fig. 5). For motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, firing rates at 20–60 % and at 55 and 60 % of MVC were significantly higher in the young subjects (~+29.7 and ~+12.8 % for motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively, p < 0.05) than in the elderly subjects, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of mean firing rates for individual motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds between the elderly and young groups during ramp contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contraction. The open and closed circles represent the elderly and young groups, respectively. The marks asterisk and number sign indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups and between force levels, respectively

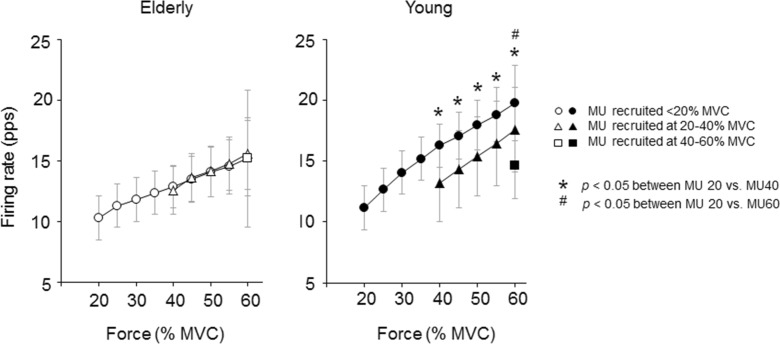

In the elderly group, there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) in firing rates among motor unit groups recruited at <20, 20–40, and 40–60 % of MVC (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Comparison of mean firing rates among individual motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds for the elderly and young groups during the ramp contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC). The circles, triangles, and squares indicate motor units (MU) recruited at <20, 20–40, and 40–60 % of MVC, respectively. The marks asterisk and number sign indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) for 20 vs. 40 % and 20 vs. 60 % of MVC, respectively

In the young group, at 40–60 % of MVC, firing rates of motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC were significantly higher than those at 20–40 % of MVC (Fig. 6, p < 0.05). Similarly, at 60 % of MVC, firing rates of motor units recruited at 20–40 % of MVC were significantly higher than those at 40–60 % of MVC (Fig. 6, p < 0.05).

The slopes of firing rates of motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC in the elderly (0.120 ± 0.069 and 0.179 ± 0.132 pps/%MVC) were significantly lower than in the young group (0.199 ± 0.072 and 0.244 ± 0.068 pps/%MVC for motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively; p < 0.05).

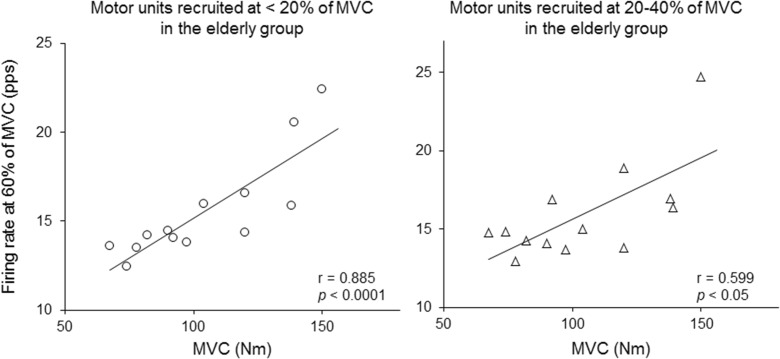

Relationship between motor unit firing pattern and MVC

In the elderly subjects performing the ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC, significant correlations were observed between the firing rates at 60 % of MVC of motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC (r = 0.885, p < 0.0001) and 20–40 % of MVC (r = 0.599, p < 0.05) and the MVC torque (Fig. 7). On the other hand, there were no significant correlations between these parameters in the young subjects (r = 0.127 and 0.018 for motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively; p > 0.05).

Fig. 7.

The relationship between the maximal voluntary contraction force and firing rate at 60 % of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) during ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC for motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC (left panel) and 20–40 % of MVC (right panel) in the elderly group

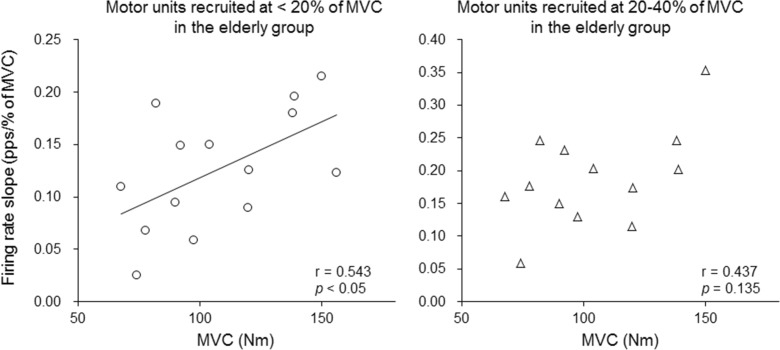

In the elderly subjects, the MVC torque was significantly correlated with the firing rate slope of motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC (r = 0.543, p < 0.05) but not with that of motor units recruited at 20–40 % of MVC (r = 0.437, p > 0.05) (Fig. 8). In the young subjects, no significant correlations between the firing rates slope and MVC torque were found (r = 0.220 and 0.203 for motor units recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively; p > 0.05).

Fig. 8.

The relationship between the maximal voluntary contraction force and firing rate slope during ramp contraction to 70 % of the maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) for motor units recruited at <20 % of MVC (left panel) and 20–40 % of MVC (right panel) in the elderly group

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare detailed firing properties of individual motor units with different recruitment thresholds in the vastus lateralis muscle during force production at low to moderate force levels between the elderly and young subjects. We also investigated the relationship between motor unit firing rates and the maximal muscle strength. The main findings of the present study were as follows: (1) at various force levels, motor unit firing rates in the elderly were lower than those in the young subjects (Figs. 2 and 5); (2) firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units are significantly higher than those of later-recruited motor units at each force level in the young but not in the elderly (Figs. 3 and 6); and (3) significant correlation existed between the motor unit firing rate and maximal muscle strength in the elderly (Figs. 7 and 8) but not in the young subjects. These results support parts of our hypotheses that firing rates of individual motor units decrease in the elderly and motor unit firing rate is associated with maximal muscle strength in the elderly. On the other hand, the hypothesis that firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units are higher than those of later-recruited motor units at any time and force in the elderly was not supported by the present results.

Decrease in motor unit firing rate in the elderly

For both ramp contractions with low and moderate force levels, firing rates of the recruited motor units in the elderly group were significantly lower than those in the young group (Figs. 2 and 5, p < 0.05). This result is in agreement with the previous studies that used small hand muscles (Erim et al. 1999; Kamen et al. 1995; Nelson et al. 1984; Patten et al. 2001; Soderberg et al. 1991) and the quadriceps femoris muscle group (Piasecki et al. 2015; Welsh et al. 2007). The reduction in the motor unit firing rate in the elderly has been explained by larger proportions of type I fibers in aged muscles (Roos et al. 1997), which are due to an increase in the innervation ratio and the selective atrophy and/or loss of type II fibers with aging (Deschenes 2004; Lexell et al. 1986; Sjostrom et al. 1986). Since the fusion of muscle contraction should occur more readily at low rates of excitation in type I fibers, the decrease in the motor unit firing rate in the elderly would be a neurophysiological adaptation to activate type I muscle fibers efficiently and minimize high-frequency fatigue (Moritani et al. 1985). In fact, Narici et al. (1991) had already showed that aged muscle was tetanized at lower fusion frequencies in the human adductor pollicis muscle by nerve stimulation (Narici et al. 1991). Also, a negative relationship between the maximal motor unit firing rate and afterhyperpolarization (AHP) in the tibialis anterior muscle was demonstrated in the elderly (r = −0.37, p = 0.004) but not in the young (r = −0.05, p = 0.72) (Christie and Kamen 2010), suggesting that AHP elongation contributes to the age-related decrease in the motor unit firing rate. It was demonstrated that the elderly have a higher firing rate per absolute unit force (Hz/N) compared with the young in the vastus medialis muscle (Ling et al. 2009) and a longer motor unit action potential area in the EMG signal (Hourigan et al. 2015; Ling et al. 2009; Piasecki et al. 2015), meaning that one motor unit innervates a greater number of muscle fibers (increase in innervation ratio). e, thus, also considered that the lower firing rate in the elderly is compensated for by greater contributions of individual motor units compared with the young to generate the required force. While we discussed our results based on selective atrophy and/or loss of type II fibers with aging (Deschenes 2004; Lexell et al. 1986; Sjostrom et al. 1986), a recent study suggested that a preferential fast fiber effect in aging muscle is not valid in very old individuals (≥80 years) or elderly with severe muscle atrophy (Purves-Smith et al. 2014). In the present study, all older individuals were ≤80 years old and the older individual with severe muscle atrophy was not included. We thus noted that motor unit firing patterns in very old individuals or elderly with severe muscle atrophy could be different from those in the elderly in the present study. The further studies would be needed to investigate motor unit firing pattern in various types of the elderly.

On the other hand, our results are inconsistent with those of Roos et al. (1999), who investigated the vastus medialis muscle (Roos et al. 1999). They showed no difference in motor unit firing rates between the young and elderly at 20~100 % of MVC during isometric knee extension. This discrepancy between the studies is believed to be due to the process of calculating the motor unit firing rate. Roos et al. (1999) calculated the mean motor unit firing rate from the motor units with various recruitment thresholds, while we divided motor units into four or three groups with different recruitment thresholds for calculation of the motor unit firing rate. It is well known that there exists an inverse relationship between the firing rate and recruitment threshold of motor units at any specified force level during gradual increases in force during isometric contraction in healthy young subjects (De Luca and Hostage 2010, 1982; Erim et al. 1996). Thus, firing rates of motor units should vary as a function of their recruitment threshold. We suspect that in the case of Roos et al. (1999), the firing behaviors of individual motor units with different recruitment thresholds were masked by the mixture of firing rates of all motor units recruited at each force level. The separation of motor units by the recruitment threshold may be necessary to detect differences in the motor unit firing rate between the elderly and young groups.

Modified relationship between the motor unit firing rate and recruitment threshold in the elderly

Some previous studies (De Luca and Hostage 2010, 1982; Erim et al. 1996) reported that the firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units are higher than those of later-recruited motor units at any time and force (known as the “onion skin phenomenon”). However, as Oya et al. (2009) stated that if motor units recruited up to 60 % of MVC are analyzed, the low-threshold motor units would generally show a higher firing rate compared with the high-threshold motor units (Oya et al. 2009). In the present study, motor unit firing rates were analyzed below 60 % of MVC and were, thereby, in accordance with the previously reported results, i.e., firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units are higher than those of later-recruited motor units. In our study, a typical pattern that is described as onion skin phenomenon was observed in ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC for the young subjects (Figs. 4 and 6). For ramp contraction to 30 % of MVC, while the firing rates of earlier-recruited motor units were generally higher than those of later-recruited motor units at each force level in both elderly and young groups, these relationships were not observed in all elderly motor unit pairs (Fig. 3). On the other hand, there was a marked difference in the relationship between the firing rate and recruitment threshold of motor units between the elderly and young for the ramp contraction to 70 % of MVC (Fig. 6). Firing rates overlapped among the motor unit groups in the elderly, whereas, in young subjects, significant differences in the firing rate were observed among the investigated motor unit groups (Fig. 6). These results suggest that the onion skin phenomenon is negated in the elderly during force production at low to moderate force levels. Deviation in the results between the ramp contraction to 30 and 70 % of MVC may be explained by different ranges in the grouping of motor units. In the present study, the range of separation in motor unit groups was greater in the ramp contraction to 70 % than to 30 % of MVC.

In the present study, while firing rates of the earlier-recruited motor unit group were higher than those of the later-recruited motor unit group at a given force level in the young, firing rates at a given force level were not different among motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds in the elderly (Fig. 6). Variation in the firing rates, which was shown in the young, would play a key role to contract different types of muscle fibers innervated by different motor neurons. In aged muscle, an increase in the innervation ratio, reinnervation, and/or a clustering of similar types of muscle fibers lead to a decrease in the inhomogeneity of muscle fiber types (Deschenes 2004; Lexell et al. 1986; Sjostrom et al. 1986). We thus estimated that a similar firing rate among different motor unit groups in the elderly may be a neurophysiological adaptation to contract similar types of muscle fibers via the hierarchical recruitment of motor units with different recruitment thresholds. Further studies are needed to clarify the physiological significance of this unique motor unit firing strategy in the elderly.

Correlation between motor unit firing patterns and maximal muscle strength in the elderly

Differences in the motor unit firing rate between the elderly and young were mainly observed at the force levels exceeding the motor unit recruitment threshold (Figs. 2 and 5). This means that differences in motor unit firing rates between the young and elderly became greater with an increase in the force level. For the ramp contractions to 70 % of MVC, the increase of firing rates with the force level were significantly greater in the young than in the elderly for motor unit groups recruited at <20 and 20–40 % of MVC, respectively. In this study, a firing rate slope was also used to investigate the relationship between motor unit firing characteristics and the maximal muscle strength. From the two different types of ramp investigated, we selected the one with higher force levels for this analysis.

In the elderly, the present study identified a correlation between MVC and motor unit firing characteristics (Figs. 7 and 8). Surprisingly, these correlations were not observed in the young. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to present the correlation of motor unit firing characteristics with maximal muscle strength in the elderly. Whereas a correlation between maximal motor unit firing rates and the MVC force was reported in the tibialis anterior muscle (r = 0.33, p = 0.002) in a previous study, this correlation was calculated jointly from elderly and young subjects (Christie and Kamen 2010). Since no correlation was observed in the young subjects in the present study, the correlation reported by Christie and Kamen (2010) may be attenuated by the lack of a significant relationship between the motor unit firing rate and maximal muscle strength in the young subjects. We thus considered that motor unit firing/recruitment properties would be a more important factor to determine the maximal muscle strength in the elderly when compared with the young.

The essential contribution of neural factors to the maximal muscle strength in the elderly has been considered since the first observation of greater improvement in neural factors, which is estimated from the surface EMG amplitude, with little muscle hypertrophy during resistance training for the elderly, reported by Moritani and deVries (Moritani and deVries 1980). Also, Christie and Kamen (2010) reported that the motor unit firing rate increased following resistance training in both the young and elderly, and this increase in the motor unit firing rate was significantly greater in the elderly (24.3 %) than in the young (6.8 %) (Christie and Kamen 2010). This suggests that the elderly exhibit a greater trainability or adaptability in motor unit firing/recruitment properties. Taking these observations together, neural factors or motor unit activation properties should be associated with the maximal muscle strength in the elderly and its decline with aging. Our results showing a correlation between motor unit firing characteristics and the maximal muscle strength in the elderly support this and suggest that a part of the inconsistency between decreases in muscle strength and muscle volume with aging (Mitchell et al. 2012) can be explained by the attenuation of motor unit activation properties in the elderly.

Limitations

There was a significant difference between the elderly and young groups in the muscle thickness (p < 0.05) but not subcutaneous tissue thickness (p > 0.05) (Table 1). When surface EMG signals are compared between the different subjects or groups, differences in the thickness of subcutaneous tissue where the electrode is attached should be considered as a nonphysiological factor which can affect the amplitude or frequency of the surface EMG signal (Minetto et al. 2013). As discussed by Holobar and Farina (2014), the thickness of subcutaneous tissue affects motor unit action potential (MUAP) shapes only, whereas the MU firing patterns remain unchanged (Holobar and Farina 2014). The SEMG decomposition used in our study effectively separates MUAP shapes from MU firing and is, thus, less sensitive to the thickness of subcutaneous layers than global EMG metrics, such as the EMG amplitude and frequency. We thus considered that the difference in muscle thickness between the groups is not critical for our findings.

The presents study employed motor tasks with very limited conditions: isometric incremental ramp contraction at a fixed force increasing rate. Previous studies demonstrated that motor unit firing/recruitment properties are influenced by the contraction speed and/or contraction type, i.e., isometric, concentric, or eccentric (De Luca et al. 1982; Moritani et al. 1987). In order to apply our findings to actual human movements, the further studies are needed to clarify the motor unit firing properties in the elderly during motor tasks under various conditions.

We selected the VL muscle because it is one of the locomotor muscles, and a previous study tested the accuracy of the decomposition process using the same equipment and analysis for the VL muscle (Holobar et al. 2009). It is known that age-related morphological changes in the skeletal muscle do not occur uniformly throughout the body. Recent studies demonstrated that the quadriceps femoris muscle group is highly susceptible to age-related muscle atrophy (Abe et al. 2011a, 2014). Therefore, we should note that our findings were demonstrated in a muscle which is sensitive to the effect of aging, and so further studies may be needed to understand the effect of aging on motor unit firing patterns in other muscle groups.

Conclusion

We investigated the motor unit firing pattern for the vastus lateralis muscle during the ramp contractions at low-moderate force levels in elderly and young subjects. The present study showed the following: (1) motor unit firing rates in the elderly are lower than those in young subjects at various force levels; (2) in the elderly, firing rates at each force level are similar among motor unit groups with different recruitment thresholds; and (3) a significant correlation exists between motor unit firing rates and the maximal muscle strength in the elderly. These results suggest that the motor unit firing rate in the quadriceps muscle is affected by aging and muscle strength in the elderly and/or age-related strength loss is likely to be related to changes in motor unit firing/recruitment properties.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japanese Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI), Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP Project ID 14533567 Funding agency: Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution, NARO), by JSPS KAKENHI, a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (No. 26750309), and by the Slovenian Research Agency (No. L5-5550).

Abbreviations

- EMG

Electromyography

- MVC

Maximal voluntary contraction

- PNR

Pulse-to-noise ratio

- SEMG

Surface electromyography

- VL

Vastus lateralis

Compliance with ethical standards

The subjects in both groups gave written informed consent for the study after receiving a detailed explanation of the purposes, potential benefits, and risks associated with participation. All procedures used in this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Chukyo University (2014–001) and were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- Abe T, Kawakami Y, Bemben MG, Fukunaga T. Comparison of age-related, site-specific muscle loss between young and old active and inactive Japanese women. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2011;34:168–173. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31821c9294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Sakamaki M, Yasuda T, Bemben MG, Kondo M, Kawakami Y, Fukunaga T. Age-related, site-specific muscle loss in 1507 Japanese men and women aged 20 to 95 years. J Sports Sci Med. 2011;10:145–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe T, Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Fukunaga T. Age-related site-specific muscle wasting of upper and lower extremities and trunk in Japanese men and women. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:813–821. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9600-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam A, de Luca CJ. Firing rates of motor units in human vastus lateralis muscle during fatiguing isometric contractions. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:268–280. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01344.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie A, Kamen G. Short-term training adaptations in maximal motor unit firing rates and afterhyperpolarization duration. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:651–660. doi: 10.1002/mus.21539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, Hostage EC. Relationship between firing rate and recruitment threshold of motoneurons in voluntary isometric contractions. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:1034–1046. doi: 10.1152/jn.01018.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca CJ, LeFever RS, McCue MP, Xenakis AP. Behaviour of human motor units in different muscles during linearly varying contractions. J Physiol Lond. 1982;329:113–128. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes MR. Effects of aging on muscle fibre type and size. Sports Med. 2004;34:809–824. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Z, De Luca CJ, Mineo K, Aoki T. Rank-ordered regulation of motor units. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:563–573. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199605)19:5<563::AID-MUS3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erim Z, Beg MF, Burke DT, de Luca CJ. Effects of aging on motor-unit control properties. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2081–2091. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.5.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Enoka RM. Surface EMG decomposition requires an appropriate validation. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:981–982. doi: 10.1152/jn.00855.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Merletti R, Enoka RM. The extraction of neural strategies from the surface. EMG J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1486–1495. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01070.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina D, Holobar A, Merletti R, Enoka RM. Decoding the neural drive to muscles from the surface electromyogram. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:1616–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuglevand AJ, Winter DA, Patla AE. Models of recruitment and rate coding organization in motor-unit pools. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:2470–2488. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.6.2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego JA, et al. The phase difference between neural drives to antagonist muscles in essential tremor is associated with the relative strength of supraspinal and afferent input. J Neurosci. 2015;35:8925–8937. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0106-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego JA, et al. Influence of common synaptic input to motor neurons on the neural drive to muscle in essential tremor. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113:182–191.. doi: 10.1152/jn.00531.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Farina D. Blind source identification from the multichannel surface electromyogram. Physiol Meas. 2014;35:R143–R165. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/35/7/R143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Zazula D. Correlation-based decomposition of surface electromyograms at low contraction forces. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2004;42:487–495. doi: 10.1007/BF02350989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Zazula D. On the selection of the cost function for gradient-based decomposition of surface electromyograms. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2008;2008:4668–4671. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2008.4650254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Farina D, Gazzoni M, Merletti R, Zazula D. Estimating motor unit discharge patterns from high-density surface electromyogram. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:551–562. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.10.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Glaser V, Gallego JA, Dideriksen JL, Farina D. Non-invasive characterization of motor unit behaviour in pathological tremor. J Neural Eng. 2012;9:056011.. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/9/5/056011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holobar A, Minetto MA, Farina D. Accurate identification of motor unit discharge patterns from high-density surface EMG and validation with a novel signal-based performance metric. J Neural Eng. 2014;11:016008. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/11/1/016008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourigan ML, McKinnon NB, Johnson M, Rice CL, Stashuk DW, Doherty TJ. Increased motor unit potential shape variability across consecutive motor unit discharges in the tibialis anterior and vastus medialis muscles of healthy older subjects. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015;126:2381–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamen G, Sison SV, Du CC, Patten C. Motor unit discharge behavior in older adults during maximal-effort contractions. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1995;79:1908–1913. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.6.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight CA, Kamen G. Modulation of motor unit firing rates during a complex sinusoidal force task in young and older adults. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:122–129. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00455.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight CA, Kamen G. Relationships between voluntary activation and motor unit firing rate during maximal voluntary contractions in young and older adults. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;103:625–630. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0757-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexell J, Downham D, Sjostrom M. Distribution of different fibre types in human skeletal muscles. Fibre type arrangement in m. vastus lateralis from three groups of healthy men between 15 and 83 years. J Neurol Sci. 1986;72:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(86)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling SM, Conwit RA, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ. Age-associated changes in motor unit physiology: observations from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1237–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.09.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merletti R, Holobar A, Farina D. Analysis of motor units with high-density surface electromyography. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2008;18:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetto MA, Holobar A, Botter A, Farina D. Discharge properties of motor units of the abductor hallucis muscle during cramp contractions. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1890–1901. doi: 10.1152/jn.00309.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetto MA, Holobar A, Botter A, Ravenni R, Farina D. Mechanisms of cramp contractions: peripheral or central generation? J Physiol. 2011;589:5759–5773. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.212332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minetto MA, Botter A, Sprager S, Agosti F, Patrizi A, Lanfranco F, Sartorio A. Feasibility study of detecting surface electromyograms in severely obese patients. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23:285–295.. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell WK, Williams J, Atherton P, Larvin M, Lund J, Narici M. Sarcopenia, dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength: a quantitative review. Front Physiol. 2012;3:260. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritani T, deVries HA. Potential for gross muscle hypertrophy in older men. J Gerontol. 1980;35:672–682. doi: 10.1093/geronj/35.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritani T, Muro M, Kijima A. Electromechanical changes during electrically induced and maximal voluntary contractions: electrophysiologic responses of different muscle fiber types during stimulated contractions. Exp Neurol. 1985;88:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritani T, Muramatsu S, Muro M. Activity of motor units during concentric and eccentric contractions. Am J Phys Med. 1987;66:338–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narici MV, Bordini M, Cerretelli P. Effect of aging on human adductor pollicis muscle function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1991;71:1277–1281. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RM, Soderberg GL, Urbscheit NL. Comparison of skeletal muscle motor unit discharge characteristics in young and aged humans. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1983;2:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(83)90029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RM, Soderberg GL, Urbscheit NL. Alteration of motor-unit discharge characteristics in aged humans. Phys Ther. 1984;64:29–34. doi: 10.1093/ptj/64.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oya T, Riek S, Cresswell AG. Recruitment and rate coding organisation for soleus motor units across entire range of voluntary isometric plantar flexions. J Physiol. 2009;587:4737–4748. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.175695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten C, Kamen G, Rowland DM. Adaptations in maximal motor unit discharge rate to strength training in young and older adults. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:542–550. doi: 10.1002/mus.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piasecki M, Ireland A, Stashuk D, Hamilton-Wright A, Jones DA, McPhee JS. Age-related neuromuscular changes affecting human vastus lateralis. J Physiol. 2015 doi: 10.1113/JP271087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purves-Smith FM, Sgarioto N, Hepple RT. Fiber typing in aging muscle. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2014;42:45–52. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos MR, Rice CL, Vandervoort AA. Age-related changes in motor unit function. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:679–690. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199706)20:6<679::AID-MUS4>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos MR, Rice CL, Connelly DM, Vandervoort AA. Quadriceps muscle strength, contractile properties, and motor unit firing rates in young and old men. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:1094–1103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199908)22:8<1094::AID-MUS14>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom M, Downham DY, Lexell J. Distribution of different fiber types in human skeletal muscles: why is there a difference within a fascicle? Muscle Nerve. 1986;9:30–36. doi: 10.1002/mus.880090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderberg GL, Minor SD, Nelson RM. A comparison of motor unit behaviour in young and aged subjects. Age Ageing. 1991;20:8–15. doi: 10.1093/ageing/20.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Akima H. Validity of surface electromyography for vastus intermedius muscle assessed by needle electromyography. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;198:332–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Kouzaki M, Fujibayashi M, Merletti R, Moritani T. Spatial EMG potential distribution pattern of vastus lateralis muscle during isometric knee extension in young and elderly men. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012;22:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Miyamoto T, Tanaka Y, Fukuda K, Moritani T. Type 2 diabetes mellitus patients manifest characteristic spatial EMG potential distribution pattern during sustained isometric contraction. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97:468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Gazzoni M, Holobar A, Miyamoto T, Fukuda K, Merletti R, Moritani T. Motor unit firing pattern of vastus lateralis muscle in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Muscle Nerve. 2013;48:806–813. doi: 10.1002/mus.23828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh SJ, Dinenno DV, Tracy BL. Variability of quadriceps femoris motor neuron discharge and muscle force in human aging. Exp Brain Res. 2007;179:219–233. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0785-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavuz US, Negro F, Sebik O, Holobar A, Frommel C, Turker KS, Farina D. Estimating reflex responses in large populations of motor units by decomposition of the high-density surface electromyogram. J Physiol. 2015;593:4305–4318. doi: 10.1113/JP270635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]