Abstract

Background: Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC). To our knowledge, low cigarette smoking (<10 cigarettes per day) has not been extensively investigated in fine categories or among never alcohol drinkers.

Methods: We conducted a pooled analysis of individual participant data from 23 independent case-control studies including 19 660 HNC cases and 25 566 controls. After exclusion of subjects using other tobacco products including cigars, pipes, snuffed or chewed tobacco and straw cigarettes (tobacco product used in Brazil), as well as subjects smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day, 4093 HNC cases and 13 416 controls were included in the analysis. The lifetime average frequency of cigarette consumption was categorized as follows: never cigarette users, >0–3, >3–5, >5–10 cigarettes per day.

Results: Smoking >0–3 cigarettes per day was associated with a 50% increased risk of HNC in the study population [odds ratio (OR) = 1.52, 95% confidence interval (CI): (1.21, 1.90). Smoking >3–5 cigarettes per day was associated in each subgroup from OR = 2.01 (95% CI: 1.22, 3.31) among never alcohol drinkers to OR = 2.74 (95% CI: 2.01, 3.74) among women and in each cancer site, particularly laryngeal cancer (OR = 3.48, 95% CI: 2.40, 5.05). However, the observed increased risk of HNC for low smoking frequency was not found among smokers with smoking duration shorter than 20 years.

Conclusion: Our results suggest a public health message that low frequency of cigarette consumption contributes to the development of HNC. However, smoking duration seems to play at least an equal or a stronger role in the development of HNC.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, low frequency cigarette smoking, risk factors, pooled analysis

Key Messages

There is no harmless level of cigarette consumption. Even smoking >0–3 cigarettes per day is associated with an increased HNC risk.

This association between low frequency of cigarette consumption and HNC risk is consistent across subsites of head and neck cancer and among never alcohol drinkers.

Smoking duration plays at least an equal or a stronger role compared with low frequency of cigarettes smoking in the development of HNC.

Introduction

Cigarette smoking is a well-established risk factor for head and neck cancer (HNC) with a well-defined dose-response relationship for duration and frequency of use. 1,2 Yet, in several epidemiological studies the lowest category of tobacco smoking has been defined as smoking ≤10 cigarettes per day. To our knowledge, only three studies have investigated the risk of HNC among participants smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day: Polesel et al ., 3 using cubic regression spline model among male current smokers only (1241 upper aerodigestive tract (UADT) cancer cases and 2 835 controls), showed evidence for an increased risk of oral cavity and pharyngeal cancer beginning at two cigarettes per day, and an increased risk of laryngeal cancer beginning at five cigarettes per day. Tuyns et al . 4 showed evidence for an increased risk of endolarynx (OR = 2.37, 95% CI: 1.3, 4.3) and of hypopharynx (OR = 4.18, 95% CI: 1.9, 9.3) associated with smoking 1 to 7 cigarettes per day compared with never smokers, adjusted for alcohol consumption. McLaughlin et al . 5 reported similar results in a 1–9 cigarettes per day category: OR = 5.2 (95% CI: 1.8, 15) for pharyngeal cancer. However, no analyses were conducted among finer cigarette smoking frequency categories or specific subgroups such as never alcohol drinkers.

Few studies have been able to address the risk of HNC among smokers of few cigarettes per day, due to the inadequate number of cases smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day. Consequently, either spline regression models needed to be utilized or broader categories of smoking frequency used.

The International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium was established in 2004 to explore the potential head and neck risk factors that were difficult to evaluate in individual studies due to limited sample size. To participate in the INHANCE consortium, studies should provide individual participant data, with data available on demographic and tumour characteristics, alcohol consumption and tobacco use habits. 6,7 . Individual participant data allow re-analysis with new hypotheses formulated, various adjustments and specific subgroup analyses.

The purpose of this study is to assess the dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and the risk of HNC among subjects smoking less than 10 cigarettes per day with better precision, while taking into account potential confounding and effect modifications. This analysis on low frequency of cigarette consumption was proposed to be performed within the INHANCE consortium database.

Methods

The version 1.4 of the INHANCE pooled dataset is an update of the version 1.0, previously described by Hashibe et al . 7 At the time of this analysis, the INHANCE V1.4 dataset included 29 case-control studies with 21 373 HNC cases and 29 548 controls.

For this analysis, we pooled data from 23 studies ( Table 1 ) with available information on cigarette, cigar and pipe smoking status, duration and frequency, satisfying the criteria for the random-effect model used (each category of the low frequency of cigarette smoking variable should have at least one case or one control) including 19 660 cases and 25 566 controls. We then excluded subjects missing information for age, sex or race and cases missing the subsite of HNC (110 cases and 127 controls). Then, to focus on the association with low cigarette smoking frequency and to avoid residual effects from other tobacco product, users of cigar, pipe, chew or snuff tobacco or straw cigarettes were excluded (3206 cases and 2913 controls). As the aim of the paper is to focus on low frequency of cigarette smoking, subjects smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day were excluded (12 251 cases and 9110 controls). The final analysis dataset included 4093 HNC cases and 13 416 controls from the 23 studies. Of the 3260 HNC cases from studies with histological information, 3067 (94.1%) were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Table 1.

Summary of individual studies in INHANCE consortium pooled data version 1.4, by region and study period

| Study location (reference a ) | Recruitment period |

Cases

|

Control

b |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Participation rate, % | Age eligibility, years | Total | Source | Participation rate, % | Total | ||

| Europe | ||||||||

| Milan, Italy | 1984–89 | Hospital | 95 c | <80 | 416 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 95 c | 1,531 |

| Aviano, Italy | 1987–92 | Hospital | >95 c | >18 | 482 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 95 c | 855 |

| Italy (Aviano, Milan, Latina) d | 1990–99 | Hospital | >95 | 18–80 | 1261 | Hospital (unhealthy) | >95 | 2,716 |

| Switzerland | 1991–97 | Hospital | >95 | <80 | 516 | Hospital (unhealthy) | >95 | 883 |

| Central Europe (Banska Bystrica, Bucharest, Budapest, Lodz, Moscow) d | 1998–2003 | Hospital | 96 | ≥15 | 762 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 97 | 907 |

| Rome f | 2002–07 | Hospital | 98 | >18 | 275 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 94 | 293 |

| Western Europe f | 2000–05 | Hospital | 82 | NA | 1701 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 68 | 1,993 |

| Germany-Heidelberg f | 1998–2000 | Hospital | 96 | <80 | 246 | Community | 62.4 | 769 |

| North America | ||||||||

| New York d,f | 1981–90 | Hospital | 91 | 21-80 | 1118 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 97 | 906 |

| Seattle, WA | 1985–1995 | Cancer registry | 54.4, 63.3 e | 18–65 | 407 | Random digit dialling | 63.0, 60.9 e | 607 |

| Iowa | 1993–2006 | Hospital | 87 | >18 | 546 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 92 | 759 |

| North Carolina | 1994–97 | Hospital | 88 | >17 | 180 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 86 | 202 |

| Tampa, FL | 1994–2003 | Hospital | 98 | ≥18 | 207 | Cancer screening clinic (healthy) | 90 | 897 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 1999–2004 | Cancer registry | 49 | 18–65 | 417 | Households Neighborhood | 67.5 | 1005 |

| Houston, TX | 2001–06 | Hospital | 95 | ≥18 | 830 | Hospital visitors | >80 | 865 |

| Boston, MA f | 1999–2003 | Hospital | 88.7 | ≥18 | 584 | Resident list | 48.7 | 659 |

| US multicentre (New York, San Francisco, New Jersey, Atlanta) d,f | 1983–84 | Cancer registry | 75 | 18-79 | 1114 | Random digit dialling, health care financing administration rosters | 76 | 1268 |

| Seattle-Leo, WA f | 1983–87 | Cancer registry | 81 | 20–74 | 634 | Random digit dialling | 75 | 445 |

| North Carolina population-based f | 2002–2006 | Cancer registry | 82 | 20–80 | 1368 | DMV files g | 61 | 1396 |

| Latin America | ||||||||

| Puerto Rico | 1992–95 | Cancer registry | 71 | 21–79 | 350 | Residential records | 83 | 521 |

| Latin America (Buenos Aires, Havana, Goiãnia, Pelotas, Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo) d (NA) | 2000–03 | Hospital | 95 | 15–79 | 2191 | Hospital (unhealthy) | 86 | 1706 |

| Sao Paulo d,f | 2002–07 | Hospital | >95 | 17–96 | 1288 | Hospital (unhealthy) | >95 | 1075 |

| International | ||||||||

| International (Italy, Spain, Ireland, Poland, Canada, Australia, Cuba, India, Sudan) d | 1992–97 | Hospital | 88.7 | NA | 1559 | Hospital/ Community | 87.3 | 1676 |

a INHANCE, International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology; NA, not applicable/non available.

b All studies frequency-matched control subjects to case subjects on age and sex. Additional frequency-matching factors included study centre (Italy, Central Europe, Latin America and International multicentre studies), hospital (France and Sao Paulo study), ethnicity (Tampa and US multicentre studies), and neighborhood or city of residence (Los Angeles and Sao Paulo study).

c Participation rate was not formally assessed, estimated response rate reported.

d Multicentre study.

e Two response rates are reported because data were collected in two population-based case-control studies, the first from 1985 to 1989 among men and the second from 1990 to 1995 among men and women.

f Study added to the INHANCE 1.0 dataset.

g Department of Motor Vehicles files.

The number of cigarettes per day was defined differently among studies. It was either a lifetime average consumption (the Houston, Tampa, Puerto Rico, Rome, North Carolina (1994–97), Milan (1984–989), Aviano, Italy multicentre, Switzerland, New York multicentre, Iowa, US multicentre, Seattle-Leo, Western Europe, North Carolina (2002–06) studies) or a period-specific frequency, usually by decades, changing habits or changing brand period (the Los Angeles, Seattle, Boston, Central Europe, International multicentre, Latin America, Sao Paulo, Germany-Heidelberg studies). In the pooled analysis we used the lifetime average daily consumption by adding the information when it was directly available or calculating it by weighing each frequency of cigarette smoking by its specific duration of consumption. We also added a reference that provides more details (Hashibe et al . 2009). 8

The frequency of cigarette smoking was defined in four categories (never cigarette users, >0–3 cigarettes per day, >3–5, >5–10) and analyses were conducted in the overall study population, among never alcohol users, for subsites of HNC (oral cavity, hypopharynx, oropharynx, oral cavity/pharynx not specified, and larynx, detailed in Hashibe et al . 2007), 7 by gender and among the different categories of duration of cigarette smoking and age at start of smoking cigarettes. One additional variable was created: combining low frequency of cigarette smoking categories and duration of cigarette smoking categories (<=10 years, 10–20 years and >20 years).

Statistical analysis

The association of low-frequency cigarette smoking with HNC was assessed by estimating odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals based on unconditional logistic regression models. To calculate summary estimates of associations, the study-specific estimates were included in a multivariate two-stage random-effects logistic regression model that included the DerSimonian and Laird estimator 9 which allows for unexplained sources of heterogeneity among studies. Pooled odds ratios were also estimated with a fixed-effects logistic regression model that adjusted for age (5-year categories), sex, education (categorical), race/ethnicity, study/study centre and number of alcoholic drinks per day (categorical). Number of drinks per day was set as a categorical variable to minimize the impact of the highest values. The Latin America and Sao Paulo studies did not assess race/ethnicity, thus we classified the subjects as a separate category ‘Latin Americans-Brazilian’.

Since 246 cases and 454 controls were missing education level, we applied multiple imputations (five imputations) with the PROC MI procedure in SAS. We assumed that the education data were missing at random (i.e. whether education was missing or not did not depend on any other unobserved or missing values. 10 We used the logistic regression model 11 to predict education level with age, sex, race/ethnicity, study centre and case/control status within each region (Europe, North America, Latin America and Asia) separately. The logistic regression results to assess summary estimates for low cigarette smoking frequency for the five imputations were combined by the PROC MIANALYZE procedure.

We tested for heterogeneity across studies, using a likelihood ratio test derived from fitting a model with and a model without a product term between low cigarette smoking and the study indicator. Then, we compared twice the difference of the log likelihood ratio of these two models, with a chi square distribution. The degree of freedom of the test was the number of studies minus one. When heterogeneity between studies was detected ( P < 0.05), the random-effect estimates were reported, otherwise the fixed-effects estimates were reported. We examined whether the results from the two-stage random-effects model and the fixed-effects logistic regression model were comparable in magnitude of effect. When random-effect estimates were estimated, individual studies missing cases or controls for any of the low cigarette consumption frequency categories were excluded, in order to have homogeneous contribution of studies across categories. We also conducted influence analysis, where each study was excluded one at a time to assure that the statistical significance and magnitude of the overall summary estimate was not dependent on any particular study. The trend test used for the analysis was a Cochrane–Armitage test.

A specific analysis was conducted after exclusion of oropharyngeal cancer cases. There is strong evidence that a large proportion of oropharyngeal cancers are caused by human papillomaviruses and are not related to tobacco smoking. 12,13 Analyses were then stratified by cancer site, age category (<40, 40–<45, 45–<50, 50–<55, 55–<60, 60–<65, 65–<70, 70–<75, > = 75 years old), sex, race/ethnicity, education level, source of control subjects (hospital-based vs population-based), and geographical region (Europe, North America, South/ Central America, others). We also repeated the analyses restricting the cases to SCC histology within the set of studies that had collected histology information.

Results

The distributions of cases and controls by selected characteristics are reported in Table 2 . The proportion of cigarette smokers smoking a lifetime average ≤5 cigarettes per day was 72.8% among controls and 27.2% among cases. The highest proportion of smokers of ≤ 5 cigarettes per day were from the Boston study (63.5%) and the Los Angeles study (57.4%). Women were more likely than men to smoke a lifetime average of ≤5 cigarettes per day (43.0% vs 33.8%). Participants smoking ≤5 cigarettes per day were more likely to start smoking at a later age, for a shorter duration and to be former smokers (participants who stopped smoking for more than 1 year before answering the questionnaire) compared with participants smoking more than 5 cigarettes per day ( P < 0.01 for each comparison).

Table 2.

Selected characteristics of the head and neck case subjects and controls subjects c from the INHANCE consortium

|

Cases

|

Controls

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Total | 4093 | 13416 | ||

| Age categories (years) | ||||

| <40 | 331 | 8.1 | 1149 | 8.6 |

| 40–<45 | 235 | 5.7 | 939 | 7.0 |

| 45–<50 | 369 | 9.0 | 1353 | 10.1 |

| 50–<55 | 521 | 12.7 | 1876 | 14.0 |

| 55–<60 | 628 | 15.3 | 2065 | 15.4 |

| 60–<65 | 597 | 14.6 | 1927 | 14.4 |

| 65–<70 | 519 | 12.7 | 1806 | 13.5 |

| 70–<75 | 476 | 11.6 | 1378 | 10.3 |

| >=75 | 417 | 10.2 | 923 | 6.9 |

| Pa | <0.0001 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Women | 1678 | 41.0 | 5875 | 43.8 |

| Men | 2415 | 59.0 | 7541 | 56.2 |

| Pa | 0.002 | |||

| Race | ||||

| White | 2655 | 64.9 | 9968 | 74.3 |

| Black | 273 | 6.7 | 655 | 4.9 |

| Hispanic | 103 | 2.5 | 330 | 2.5 |

| Asian | 111 | 2.7 | 472 | 3.5 |

| Other | 30 | 0.7 | 110 | 0.8 |

| Brazilian d | 921 | 22.5 | 1881 | 14.0 |

| Pa | <0.0001 | |||

| Education | ||||

| None | 129 | 3.4 | 272 | 2.1 |

| Junior high school | 1447 | 37.6 | 4533 | 35.0 |

| Some high school | 560 | 14.6 | 1856 | 14.3 |

| High school graduate | 513 | 13.3 | 1674 | 12.9 |

| Vocational, some college | 602 | 15.7 | 2343 | 18.1 |

| Some graduation | 596 | 15.5 | 2284 | 17.6 |

| Missing b | 246 | 454 | ||

| Pa | <0.0001 | |||

| Subsite | ||||

| Oral cavity | 1327 | 32.4 | ||

| Oropharynx | 1179 | 28.8 | ||

| Hypopharynx | 230 | 5.6 | ||

| Oral cavity/pharynx NOS e | 488 | 11.9 | ||

| Larynx | 797 | 19.5 | ||

| Head and neck overlap | 72 | 1.8 | ||

a Chi-square two-sided test.

b Rome does not have information on education.

c Missing for age, sex, race and subsite as well as users of pipe or cigar or chewed tobacco. Snuffed tobacco or straw cigarettes were excluded.

d Only cases and controls from Sao Paulo and Latin America study.

e Not Otherwise Specified.

HNC risk increased with greater smoking frequency in the overall study population, after exclusion of oropharyngeal cancer cases and among never alcohol drinkers ( P for trend <0.01; Table 3 ). The OR for the category of >0–3 cigarettes/day was 1.52 (95% CI: 1.21, 1.90) for the overall study population and 1.35 (95% CI: 0.83, 2.18) among never alcohol drinkers. The association between smoking >3–5 cigarettes per day and the risk of HNC was observed among the overall study population (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 1.73, 2.65) and among never alcohol drinkers (OR = 2.01, 95% CI: 1.22, 3.31).

Table 3.

Lifetime average daily number of cigarettes smoked and the risk of HNC, among the overall population and among never alcohol drinkers, in the INHANCE consortium

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day |

Overall

a |

Never alcohol drinkers

b |

Overall without oropharyngeal cases

c |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | OR d | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR d | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR d | 95% CI | |

| Never | 1939 | 9239 | 1.00 | Ref | 724 | 2836 | 1.00 | Ref | 1635 | 8821 | 1.00 | Ref |

| >0–3 | 250 | 793 | 1.52 | (1.21, 1.90) | 41 | 123 | 1.35 | (0.83, 2.18) | 212 | 779 | 1.56 | (1.25, 1.93) |

| >3–5 | 314 | 710 | 2.14 | (1.73, 2.65) | 38 | 89 | 2.01 | (1.22, 3.31) | 278 | 680 | 2.30 | (1.88, 2.81) |

| >5–10 | 1258 | 2215 | 2.60 | (2.00, 3.40) | 131 | 286 | 2.12 | (1.48, 3.02) | 1137 | 2125 | 2.98 | (2.31, 3.82) |

| Missing | 332 | 459 | 11 | 13 | 299 | 451 | ||||||

| P- value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

| P for heterogeneity across studies | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||||

a Adjusted on age (categorical), sex, race, education level, centres and drinks per day (categorical). The 23 studies were included.

b Adjusted on age (categorical), sex, race, education level and centres. The Switzerland, New York multicentre, Iowa, Los Angeles, Houston, Puerto Rico, Latin America, IARC multicentre, Sao Paulo, Western Europe and North Carolina population-based studies were included.

c Adjusted on age (categorical), sex, race, education level, centres and drinks per day. The 23 studies, except for the North Carolina and Tampa studies, were included.

d Random-effect model used.

Results by HNC subsite demonstrated the strongest dose-response relationship for hypopharyngeal and laryngeal cancer ( P for trend <0.01; Table 4 ). For these subsites, the OR for smokers of >0–3 category cigarettes/day was 2.43 (95% CI: 1.23, 4.79) for hypopharynx and 2.68 (95% CI: 1.82, 3.95) for larynx.

Table 4.

Lifetime average daily number of cigarettes smoked and the risk of HNC by subsite of cancer, in the INHANCE consortium

| Daily number of cigarette smoked |

Oral cavity

a |

Hypopharynx

b |

Oropharynx

c |

Larynx

d |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | OR e | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR e | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR e | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR e | 95% CI | |

| Never | 653 | 6309 | 1.00 | 38 | 3521 | 1.00 | 520 | 7368 | 1.00 | 203 | 6010 | 1.00 | ||||

| >0–3 | 62 | 548 | 1.48 | (1.04, 2.09) | 13 | 3443 | 2.43 | (1.23, 4.79) | 70 | 661 | 1.57 | (1.10, 2.23) | 58 | 581 | 2.68 | (1.82, 3.95) |

| >3–5 | 79 | 474 | 2.23 | (1.45, 3.42) | 17 | 310 | 3.35 | (1.78, 6.29) | 64 | 528 | 2.17 | (1.53, 3.06) | 74 | 518 | 3.48 | (2.40, 5.05) |

| >5–10 | 291 | 1501 | 2.18 | (1.68, 2.83) | 71 | 1032 | 4.38 | (2.82, 6.82) | 323 | 1724 | 2.85 | (1.89, 4.08) | 309 | 1543 | 5.21 | (4.07, 6.68) |

| Missing | 104 | 407 | 8 | 244 | 51 | 398 | 92 | 324 | ||||||||

| P -value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

| P for heterogeneity across studies | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||||||||

Adjusted on age (categorical), race, education level, centres and drinks per day (categorical).

a The Aviano, Boston, Los Angeles, Milan, North Carolina, Rome, Switzerland, Tampa, Seattle-LEO and Germany-Heidelberg studies were not included.

b Only Aviano, Italy multicentre, New York, Latin America, US multicentre, Seattle-LEO and Western Europe studies were included.

c The Milan, Central Europe, Seattle, North Carolina, Tampa, Boston, and Germany-Heidelberg studies were not included.

d Only Milan, Central Europe, Italy Multicentre, New York, Iowa, Los Angeles, Latin America, Boston, Rome, Sao Paulo, Seattle-LEO, Western Europe, Germany-Heidelberg and North Carolina population-based studies were included.

e Random-effect models.

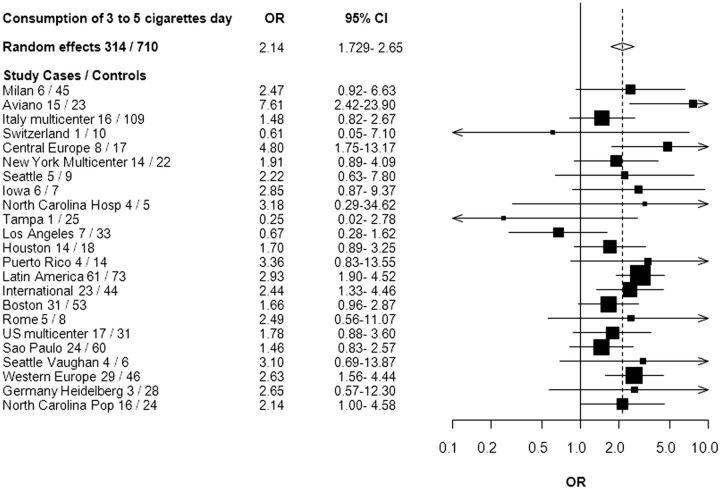

Although the point estimates were slightly higher among women than men, the 95% CIs overlapped ( Table 5 ). We observed that women smoking >0–3 cigarettes per day had an increased risk of HNC (OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.30, 2.40) compared with never smokers. For the combination of frequency and duration of smoking, we observed an association between HNC and each stratum of the low frequency of cigarette consumption with the highest stratum of smoking duration ( Table 6 ). Figure 1 shows a forest plot of the study-specific estimates for the risk of HNC associated with smoking 3 to 5 cigarettes per day. All studies but Switzerland, Tampa and Los Angeles showed an increased risk of HNC for smoking 3 to 5 cigarettes per day. There was also an increased risk of smoking >0 to 3 cigarettes per day among current smokers (OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.53, 2.81) and among former smokers (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.05, 1.66).

Table 5.

Lifetime average daily number of cigarettes smoked and the risk of HNC by gender, in the INHANCE consortium

| Daily number of cigarettes smoked |

Men

a |

Women

b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | OR c | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR c | 95% CI | |

| Never | 853 | 4099 | 1.00 | 882 | 3763 | 1.00 | ||

| >0–3 | 141 | 480 | 1.39 | (0.96, 2.01) | 101 | 278 | 1.77 | (1.30, 2.40) |

| >3–5 | 160 | 409 | 2.05 | (1.39, 3.02) | 118 | 200 | 2.74 | (2.01, 3.74) |

| >5–10 | 854 | 1420 | 2.83 | (2.01, 3.98) | 330 | 556 | 2.67 | (2.02, 3.53) |

| Missing | 235 | 250 | 84 | 180 | ||||

| P- value | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| P for heterogeneity across studies | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

Adjusted on age (categorical), race, education level, centres and drinks per day (categorical).

a The Boston, North Carolina, Tampa, Switzerland and Seattle-LEO studies were not included.

b The Boston, Milan, Rome, Tampa and Germany-Heidelberg studies were not included.

c Random-effect models.

Table 6.

Adjusted OR (95% CI) of HNC by lifetime average daily number of cigarettes smoked combined with duration of cigarette smoking in years, in the INHANCE consortium

| Cigarattes daily | Cases | Controls | OR a , b | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never smokers | 1163 | 4329 | 1.00 | Ref |

| >0–3 cig for <=10 yrs | 53 | 199 | 1.04 | (0.75, 1.43) |

| >0–3 cig for >10–20 yrs | 27 | 77 | 1.39 | (0.88, 2.20) |

| >0–3 cig for >20–30 yrs | 29 | 79 | 1.30 | (0.83, 2.03) |

| >0–3 cig for >30 yrs | 76 | 104 | 2.64 | (1.92, 3.63) |

| >3–5 cig for <=10 yrs | 30 | 98 | 1.04 | (0.68, 1.59) |

| >3–5 cig for >10–20 yrs | 22 | 70 | 1.19 | (0.72, 1.96) |

| >3–5 cig for >20–30 yrs | 37 | 55 | 2.35 | (1.52, 3.65) |

| >3–5 cig for >30 yrs | 101 | 105 | 2.89 | (2.13, 3.91) |

| >5–10 cig for <=10 yrs | 52 | 167 | 1.06 | (0.76, 1.47) |

| >5–10 cig for >10–20 yrs | 55 | 220 | 0.94 | (0.68, 1.29) |

| >5–10 cig for >20–30 yrs | 130 | 221 | 1.91 | (1.49, 2.43) |

| >5–10 cig for >30 yrs | 541 | 412 | 4.17 | (3.54, 4.90) |

| Missing | 229 | 164 | ||

| P for heterogeneity | 0.05 | |||

| P for trend | <0.01 |

Adjusted on age (categorical), race, education level, centres and drinks per day (categorical); yrs, years.

a The Los Angeles, International Multicentre, US multicentre, Sao Paulo, Western Europe, North Carolina (population-based) studies were included.

b Fixed-effect model.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the risk of HNC associated with lifetime consumption of 3 to 5 cigarettes per day compared with never smokers, in the INHANCE Consortium. Pop, population-based; hosp, hospital.

An analysis stratified by study design showed positive monotonic trends of increasing risks with increasing frequency of cigarette smoking for both hospital-based ( n = 15) and population-based ( n = 9) studies (the Western Europe study includes studies with both population-based and hospital-based controls), with a slightly weaker trend in population-based studies (OR = 1.64, 95% CI: 0.90, 3.00; OR = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.31, 2.85; OR = 2.51, 95% CI: 1.50, 4.18 for > 0–3, >3–5 and >5–10 cigarettes/day, respectively; P for trend <0.01). When the analysis by region was conducted, an apparent positive trend of increasing risks with increasing frequency of cigarette smoking was observed in each region. Such relationship was found to be strongest in Europe and Latin America. The risk of HNC for smoking >0 to 3 cigarette per day was OR = 1.82 (95% CI: 1.15, 2.86) in Europe and OR = 1.98 (95% CI: 1.15, 3.39) in Latin America. Analyses restricted to squamous cell carcinoma yielded similar results (see Appendix Table 1 A, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

We additionally adjusted, when the information was available, for body mass index (BMI) (all studies except for Rome, Seattle, International multicentre, Iowa, Central Europe, Sao Paulo, Germany-Heidelberg) and for family history of HNC (all studies except for Rome, Seattle, New York multicentre, Iowa, Western Europe and Seattle-Leo). The magnitudes of the associations were similar to those observed without the additional adjustments (see Appendix Table 1 A, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Analysis of passive smoking was not conducted as this information was only available in six studies (Central Europe, Latin America, Puerto Rico, Tampa, Los Angeles and Houston), and this would have resulted in a restricted number of cases and controls. However, based on our previous analysis on passive smoking, 14 the modest association with passive smoking was observed among never tobacco users. Thus, we suspect the dose-response relationship among smokers presented here would not be significantly biased.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess whether or not one or several studies had a strong influence on the observed associations. When we omitted each study from the analysis one at a time, the Aviano and the Tampa studies accounted for heterogeneity the most. When the Aviano study was not included, the summary estimate for smoking 3 to 5 cigarettes per day compared with never smokers was 2.04 (95% CI: 1.69, 2.46) and when the Tampa study was not included, the summary estimate was 2.18 (95% CI: 1.76, 2.69) as compared with the overall summary estimate of 2.14 (95% CI: 1.73, 2.65). When both studies were excluded from the summary estimate, the OR was 2.06 (95% CI: 1.71, 2.49).

The sensitivity analysis was also conducted for smoking >0 to 3 cigarettes per day. When we omitted each study from the analysis one at a time, the Seattle and the North Carolina (hospital-based) studies accounted for heterogeneity the most. When the Seattle study was not included, the summary estimate for smoking >0 to 3 cigarettes per day compared with never smokers was 1.55 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.95) and when the North Carolina study was not included, the summary estimate was 1.50 (95% CI: 1.19, 1.88) as compared with the overall summary estimate of 1.52 (95% CI: 1.21, 1.90). When both studies were excluded from the summary estimate, the OR was 1.54 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.93).

Discussion

The ability to pool individual data from studies allowed us to detect an increased risk of HNC with smoking less than 10 cigarettes more precisely than it has been reported previously by Tuyns et al . 4 and McLaughlin et al . 5 and highlighted an approximately 1.5-fold increased risk of HNC for smoking >0 to 3 cigarettes per day and a more than 2-fold increased risk of HNC for smoking >3 to 5 cigarettes per day. This also corroborates the results reported by Polesel et al . 3 that there is an increased risk regardless of the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Polesel showed evidence for an increased OR of UADT cancer for smoking two cigarettes per day. The present analysis provides additional details for the finer categories of smoking frequency with adequate sample size.

From a methodological point of view we decided to investigate the frequency of cigarette smoking as a categorical variable with fine categories instead of a continuous variable. Even though using a continuous variable might increase the precision of the estimates, it implies making some assumptions on the shape of the slope and might introduce mis-specification bias. There is no need for such assumptions when using a categorical variable. The large number of cases and controls provides for sufficient precision, and keeps the results straightforward for interpretation.

The higher increased risk of laryngeal cancer with cigarette smoking compared with the other head and neck subsites is consistent with the previous findings 12,13 and with the previous reports from INHANCE studies that active smoking is a stronger risk factor for laryngeal cancers than for oral cavity cancer among never alcohol drinkers. 7

The analysis combining the smoking frequency with smoking duration is consistent with the previous observations that duration of smoking seems to play at least an equal or a stronger role in the development of HNC 4 even among never alcohol drinkers.

A potential limitation with regards to the data pooling was the variation of definition for ‘ever cigarette smokers’ (among whom the frequency of cigarette smoking was measured) used in the different studies: ever smoked, smoked ≥100 cigarettes in a lifetime, smoked 1 cigarette/day for ≥1 year or 6 months, smoked 1 cigarette/week for ≥1 year or smoked half a pack/week for ≥1 year. However, these different classifications are relatively minor and likely to be non-differential between cases and controls. Thus, this might lead to an underestimation of the assessment. In addition, some individuals with very minimal cigarette use may have been categorized as ‘never cigarette users’ in the analysis due to the definition or the wording of the questions. The studies with higher threshold for the classification were the Tampa study (smoking cigarettes less than once a day for <1 year as never users of cigarettes) and Latin America study (<1 cigarette per day for 1 year as never cigarette smokers). However, the ORs for the lowest category of smokers (>0–3 per day) were not consistently lower or higher for these studies compared with the others included in our pooled analysis.

Recall bias may be another limitation for our pooled analysis because information about cigarette smoking and the other exposures was collected for cases after the diagnosis of HNC. However, we observed associations between low-frequency cigarette smoking in both hospital-based and population-based studies, which may be susceptible to recall bias in different degrees. In addition, there might be residual confounding by the other risk factors. However, our study sample size allowed us to investigate the association among never alcohol drinkers to eliminate the possible residual confounding by alcohol drinking. Additionally, further adjustment for body mass index and family history of HNC did not support that the observed association could be accounted for by these factors. Although heterogeneity across studies was important, in the >0–3 and 3 to 5 cigarettes per day, the sensitivity analyses showed that exclusion of studies contributing the most in the heterogeneity did not lead to major changes in the estimates for both categories.

Finally, as specified in the method section, analyses were conducted on data from studies participating in the INHANCE consortium. Some published and unpublished studies might not be included, but publication bias is not a concern for this type of analysis because we did not select studies from the literature. Additionally, the large sample size and the quality of the studies included allow our estimates to be accurate.

In summary, this pooling project provides evidence for a carcinogenic consequence of cigarette smoking at low frequency. The results of this study send a public health message to the community: there is no harmless level of cigarette consumption, even smoking >0–3 cigarettes per day is associated with an increased HNC risk. However, smoking duration seems to play at least an equal or a stronger role in the development of HNC in light smokers.

Funding

The pooled data coordination team (PBoffetta, MH, Y-CAL) were supported by National Cancer Institute grant R03CA113157 and by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grant R03DE016611

The Milan study (CLV) was supported by the Italian Association for Research on Cancer (Grant no. 10068).

The Aviano study (LDM) was supported by a grant from the Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC), Italian League Against Cancer and Italian Ministry of Research

The Italy Multicenter study (DS) was supported by the Italian Association for Research on Cancer (AIRC), Italian League Against Cancer and Italian Ministry of Research.

The Study from Switzerland (FL) was supported by the Swiss League against Cancer and the Swiss Research against Cancer/Oncosuisse [KFS-700, OCS-1633].

The central Europe study (PBoffetta, PBrenan, EF, JL, DM, PR, OS, NS-D) was supported by the World Cancer Research Fund and the European Commission INCO-COPERNICUS Program [Contract No. IC15- CT98-0332]

The New York multicentre study (JM) was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health [P01CA068384 K07CA104231].

The study from the Fred Hutchison Cancer Research Center from Seattle (CC, SMS) was supported by a National Institute of Health grant [R01CA048996, R01DE012609].

The Iowa study (ES) was supported by National Institute of Health [NIDCR R01DE011979, NIDCR R01DE013110, FIRCA TW001500] and Veterans Affairs Merit Review Funds.

The North Carolina studies (AFO) were supported by National Institute of Health [R01CA061188], and in part by a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [P30ES010126].

The Tampa study (PLazarus, JM) was supported by National Institute of Health grants [P01CA068384, K07CA104231, R01DE013158]

The Los Angeles study (Z-F Z, HM) was supported by grants from National Institute of Health [P50CA090388, R01DA011386, R03CA077954, T32CA009142, U01CA096134, R21ES011667] and the Alper Research Program for Environmental Genomics of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The Houston study (EMS, GL) was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health [R01ES011740, R01CA100264].

The Puerto Rico study (RBH, MPP) was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (NCI) US and NIDCR intramural programs.

The Latin America study (PBoffetta, PBrenan, MV, LF, MPC, AM, AWD, SK, VW-F) was supported by Fondo para la Investigacion Cientifica y Tecnologica (FONCYT) Argentina, IMIM (Barcelona), Fundaco de Amparo a` Pesquisa no Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP) [No 01/01768-2], and European Commission [IC18-CT97-0222]

The IARC multicentre study (SF, RH, XC) was supported by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS) of the Spanish Government [FIS 97/ 0024, FIS 97/0662, BAE 01/5013], International Union Against Cancer (UICC), and Yamagiwa-Yoshida Memorial International Cancer Study Grant.

The Boston study (KKelsey, MMcC) was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health [R01CA078609, R01CA100679].

The Rome study (SB, GC) was supported by AIRC (Italian Agency for Research on Cancer).

The US multicentre study (BW) was supported by The Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Health, United States.

The Sao Paolo study (V W-F) was supported by Fundacao de Ampara a Pesquisa no Estado de Sao Paulo (FAPESP No 10/51168-0)

The MSKCC study (SS, G-P Y) was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health [R01CA051845].

The Seattle-Leo stud (FV) was supported by a grant from National Institute of Health [R01CA030022]

The western Europe Study (PBoffetta, IH, WA, PLagiou, DS, LS, FM, CH, KKjaerheim, DC, TMc, PT, AA, AZ) was supported by European Community (5th Framework Programme) grant no QLK1-CT-2001- 00182.

The Germany Heidelberg study (HR) was supported by the grant No. 01GB9702/3 from the German Ministry of Education and Research.

Conflict of interest: PB is a special government employee serving for the Tobacco Product research programme of the US Food and Drug Administration.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lubin JH, Alavanja MC, Caporaso N, et al. . Cigarette smoking and cancer risk: modeling total exposure and intensity . Am J Epidemiol 2007. ; 166:479 – 89 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wyss A, Hashibe M, Chuang SC, et al. . Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking and the risk of head and neck cancers: pooled . Am J Epidemiol 2013. ; 178:679 – 90 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polesel J, Talamini R, La Vecchia C, et al. . Tobacco smoking and the risk of upper aero-digestive tract cancers: A reanalysis of case-control studies using spline models . Int J Cancer 2008. ; 122:2398 – 402 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tuyns AJ, Esteve J, Raymond L, et al. . Cancer of the larynx/hypopharynx, tobacco and alcohol: IARC international case-control study in Turin and Varese (Italy), Zaragoza and Navarra (Spain), Geneva (Switzerland) and Calvados (France) . Int J Cancer 1988. ; 41:483 – 91 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McLaughlin JK, Hrubec Z, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF, Jr . Smoking and cancer mortality among U.S. veterans: a 26-year follow-up . Int J Cancer 1995. ; 60:190 – 93 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conway DI, Hashibe M, Boffetta P, et al. . Enhancing epidemiologic research on head and neck cancer: INHANCE –The international head and neck cancer epidemiology consortium . Oral Oncol 2009. ; 45:743 – 46 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al. . Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium . J Natl Cancer Inst 2007. ; 99:777 – 89 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang S-C, et al. . Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium . Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009. ; 18:541 – 50 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DerSimonian R, Laird N . Meta-analysis in clinical trials . Control Clin Trials 1986. ; 7:177 – 88 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Greenland S, Finkle WD . A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses . Am J Epidemiol 1995. ; 142:1255 – 64 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rudin D . Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys . New York, NY: : John Wiley; , 1987. . [Google Scholar]

- 12. IARC working group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans . Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking . Lyon, France: : IARC Press; , 2004. . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D’Avanzo B, La Vecchia C, Talamini R, Franceschi S . Anthropometric measures and risk of cancers of the upper digestive and respiratory tract . Nutr Cancer 1996. ; 26:219 – 27 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee Y-CA, Boffetta P, Sturgis EM, et al. . Involuntary smoking and head and neck cancer risk: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium . Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008. ; 17:1974 – 81 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.