Abstract

Olfactory dysfunction is a common complaint among physician visits. Olfactory loss affects quality of life and impairs function and activities of daily living. The purpose of our study was to assess the degree of odor identification associated with mental health. Olfactory function was measured using the brief smell identification test. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale. Loneliness was assessed by the de Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale. Cognition was measured by a battery of 19 cognitive tests. The frequency of olfactory dysfunction in our study was ~40%. Older subjects had worse olfactory performance, as previously found. More loneliness was associated with worse odor identification. Similarly, symptoms of depression were associated with worse olfaction (among men). Although better global cognitive function was strongly associated with better odor identification, after controlling for multiple factors, the associations with depression and loneliness were unchanged. Clinicians should assess these mental health conditions when treating older patients who present with olfactory deficits.

Key words: cognition, demographics, demography, depression, loneliness, olfaction, retirement communities, retirement homes

Introduction

Nearly 14 million older Americans suffer from olfactory complaints leading to approximately 200000 physician visits annually (Wysocki and Gilbert 1989; Hoffman et al. 1998; Murphy et al. 2002). As the US population continues to age, the clinical impact of olfactory dysfunction will increase. Olfactory loss affects quality of life and impairs function and activities of daily living such as personal hygiene, eating meals, and detecting dangers in the environment (e.g., smoke, gas, spoiled food) (Doty 2015).

In contrast to other major sensory impairments such as decline of vision or hearing, the association of olfactory decline with mental health problems is less characterized. Chemosensation is a form of social communication and a mode of experiencing pleasure, so its decline would be expected to have consequences for personal interaction and emotion.

Anecdotally, clinicians often observe that olfactory loss causes great burdens in mental health for patients. Much of the previous work on the associations between olfaction and specific mental health conditions has focused on patients with olfactory complaints who were referred for evaluation to specialized smell clinics (Deems et al. 1991; Temmel et al. 2002; Hummel and Nordin 2005). Studies supporting clinical impressions of a connection are sparse, though links have been made between olfactory loss and loneliness (Steinbach et al. 2008). Additionally, limited evidence suggests that olfactory loss is associated with depression (Naudin et al. 2012; Croy et al. 2014a, 2014b). However, there have been few studies that have objectively measured the relationship between olfaction and mental health in more typical community-based populations.

We hypothesized that worse olfaction would be associated with both depression and loneliness. In previous studies, we showed a close relationship between odor identification and cognitive decline (Wilson et al. 2006). Thus, we wanted to account for its effect on odor identification in our analysis of the connection to mental health in order to reveal any relationship between these neuropsychiatric conditions and olfactory dysfunction.

To test this hypothesis, we utilized data from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a prospective, longitudinal cohort study of older adults who were without known dementia at baseline and followed for the development of common neurodegenerative diseases (Bennett et al. 2012). These data include information on olfactory performance (odor identification) using a validated test, medical history, detailed neurological examination, and comprehensive assessment of cognitive function, and measures of depression and loneliness, among other relevant covariates (Wilson et al. 2006; Bennett et al. 2012).

Materials and methods

Participants

The Rush MAP is an ongoing longitudinal study of risk factors associated with common chronic neurodegenerative conditions in older adults (Bennett et al. 2012). Beginning in 1997, participants without known dementia underwent annual clinical evaluations. The Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois approved this study. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Briefly, subjects in the greater Chicago metropolitan area were recruited from retirement communities, senior citizen housing facilities, church groups, and senior centers. At the time of enrollment and thereafter, each subject underwent an extensive clinical evaluation, including medical history, neurological examination, detailed cognitive function testing, and assessment of odor identification ability. Detailed information on the MAP study design and the evaluation protocol is provided elsewhere (Bennett et al. 2012). Most relevant to these analyses are demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, physical health, olfactory testing, and cognitive function testing, described later.

Odor identification

The ability to identify odors was assessed at baseline using the brief smell identification test (B-SIT, Sensonics), a validated, cross-culturally appropriate 12-item scratch and sniff test (Doty et al. 1989, 1996). A microcapsule containing a familiar odor was scratched with a pencil and was placed under the nose of the participant, who attempted to match the smell with 1 of 4 choices. The score was the number of odors correctly recognized. A “don’t know” or “refused” answer was counted as incorrect. Those who responded “don’t know” or “refused” to all 12 questions were assigned a score of 0. Scores on the B-SIT correspond well to the 40-item University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test from which it was derived (r = 0.85) (Doty et al. 1984, 1989).

Mental health

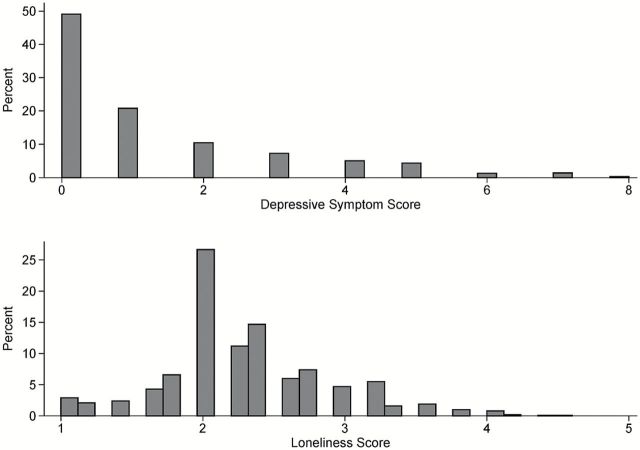

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Kohout et al. 1993; Andresen et al. 1994; Irwin et al. 1999; Miller et al. 2008). Based on DSM-V criteria, the CES-D measures depressive symptoms to screen for depression. Despite being a shorter screening questionnaire as compared with the 20-item version of the CES-D, the 10-item questionnaire has shown good predictive accuracy (Andresen et al. 1994; Irwin et al. 1999; Miller et al. 2008) and has been previously validated (Kohout et al. 1993). For analysis purposes, due to the skewness of the distribution (Figure 1), presence of any depressive symptoms (i.e., a score of 1 or more) was used.

Figure 1.

Distributions of the depressive symptom score and loneliness score.

Loneliness was measured using a 5-item modified version of the de Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale with a total score that ranged from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating more loneliness (de Jong-Gierveld and Kamphuis 1985; de Jong-Gierveld 1987; for additional details on phenotyping, see Wilson et al. 2007) (Figure 1). This questionnaire includes questions about “emotional loneliness” (when a person misses an intimate relationship) and “social loneliness” (when a person misses a wider social network).

Assessment of cognitive function

Cognitive function was determined using a battery of neuropsychological tests administered during a 1-h session. The Mini-Mental State Examination was used for descriptive purposes. The primary measure of cognition was based on 19 other tests which included 7 measures of episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall of the East Boston Story and Story A from Logical Memory and Word List Memory, Word List Recall, and Word List Recognition), 3 measures of semantic memory (15-item version of the Boston Naming Test, a 15-item reading recognition test, and Verbal Fluency), 3 tests of working memory (Digit Span Forward, Digit Span Backward, and Digit Ordering), 4 tests of perceptual speed [oral version of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Number Comparison, 2 measures from a modified Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test (the number of color names correctly read in 30s minus the number of errors and the number of colors correctly named in 30s minus errors)], and 2 tests of visuospatial ability (16-item version of Standard Progressive Matrices and a 15-item version of Judgment of Line Orientation) (Wilson et al. 2007). All testing listed were administered at baseline.

Raw scores on each of the 19 tests were converted to z scores by using the baseline mean and standard deviation (SD) in the cohort. By averaging the z scores of the component tests, a composite score was developed. This composite score represents a measure of global cognition. Detailed information on the individual test results and on the derivation of these composite scores can be found elsewhere (Wilson et al. 2006; Bennett et al. 2012).

We quantified the degree to which odor identification is affected by cognitive function because it requires higher processing to recall and name a choice among 4 options to answer each question on the B-SIT and therefore may bias the relationship between olfaction and mental health.

Other covariates

Age was calculated from birth year to date of test administration. Sex was self reported as was years of education. Vascular disease burden, a measure of comorbidity, was constructed as the number of conditions present (claudication, stroke, heart attack, and congestive heart failure) based on a combination of self-report, clinical examination, and medication inspection as previously reported (Boyle et al. 2005). Vascular risk burden was the number of the following conditions present (self-report of physician diagnosis or found to be on medication for these conditions): hypertension, diabetes, or smoking history as previously reported (Boyle et al. 2005). Lifetime daily alcohol intake was calculated as the number of alcoholic drinks (beer, wine, or liquor) consumed per day during the period that the participant drank the most in their lifetime.

Statistical analysis

We tested the association of odor identification score with CES-D score (presence of at least 1 symptom) and the de Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale, adjusting for age, sex, education, vascular disease burden, lifetime alcohol use, and the global cognition score using a series of ordinal logistic regression models. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. The key assumption in ordinal logistic regression is that the effect of any independent variable is proportional or consistent across the different performance thresholds/cut-points (e.g., >2 correct, >5 correct, or >9 correct). Thus, an OR from the ordinal logistic regression model can be interpreted as the odds of meeting a given performance criterion/threshold (or in other words, the odds of correctly identifying more odors) for one group versus another. The proportionality assumption was tested using a likelihood-ratio test, which indicated that there was some modest evidence for departure from proportionality. Because this test is often anticonservative, the final ordinal logistic regression model was rerun after collapsing outcome categories so that there were 4 categories based on the quartiles of the odor identification score. With this model, the proportionality assumption was confirmed (P = 0.54) and the effect sizes were very close to that found in the original analysis (data not shown). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis using linear regression. An assessment of the predictive discrimination, using Kendall’s tau, for the ordinal logistic and linear regression models indicated that the ordinal logistic regression model performed slightly better. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata Version 13 (StataCorp).

Results

Subjects

There were 1200 MAP participants who completed the olfactory identification assessment at the baseline evaluation. Because of the low number of racial and ethnic minority subjects (and therefore limited power to detect effects in these subgroups) and known racial disparities in olfaction (Pinto et al. 2014), we limited our analyses to non-Hispanic whites (n = 1018). Mean age was 80.4 years (SD = 7.0, range 54–100) and 73.4% were women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population characteristics (N = 1018)

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Odor identification score (no. of correct) | 1018 | 8.3 (2.9) | 0–12 |

| Men | 271 (26.6%) | ||

| Age (years) | 1018 | 80.4 (7.0) | 54–100 |

| >High school education | 702 (69.0%) | ||

| Income ($) | |||

| <25000 | 287 (28.2%) | ||

| 25000–49999 | 353 (34.7%) | ||

| 50000+ | 294 (28.9%) | ||

| Missing/unknown | 84 (8.2%) | ||

| Loneliness score | 1002 | 2.3 (0.60) | 1–4.6 |

| Depressive symptom score | 1012 | 1.3 (1.7) | 0–8 |

| Presence of any symptoms | 515 (50.9%) | ||

| Vascular disease (no. of conditions) | 1018 | 0.3 (0.6) | 0–3 |

| Vascular risk (no. of conditions) | 1018 | 1.0 (0.8) | 0–3 |

| Lifetime daily alcohol intake | 1010 | 0.6 (1.1) | 0–6 |

| Global cognition score | 1014 | 0.04 (0.64) | −3.83 to 1.41 |

Olfactory function

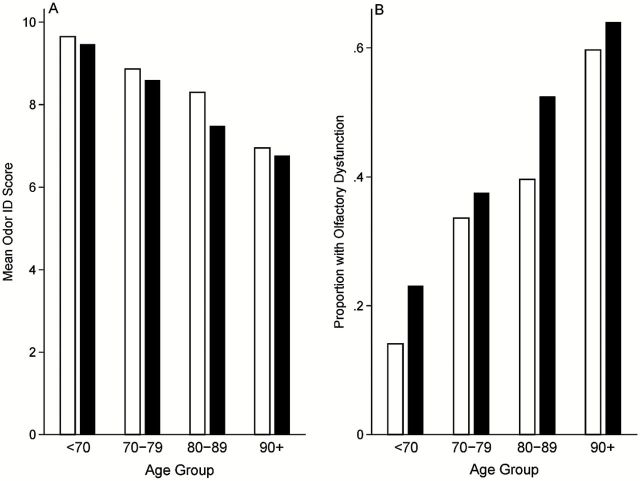

The mean odor identification score was 8.3 (SD = 2.9). A summary of olfactory performance by gender is provided in Table 2. Only 6.0% of subjects responded correctly to all 12 odorants and 17.9% identified 11 odorants. A large percentage of subjects were found to have olfactory dysfunction, defined as 8 or fewer correct (39.7%) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Summary of odor identification, loneliness, and depressive symptoms by gender

| Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| Odor identification score (no. of correct) | 7.9 (3.2) | 8.5 (2.8) |

| Loneliness score | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.6) |

| Depressive symptom score | 0.9 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.8) |

Figure 2.

(A) Observed olfactory function by gender and age group. (B) Observed proportion of MAP subjects with olfactory dysfunction by gender and age group. White bars = women, black bars = men.

Models of olfactory function

Demographics

As expected, olfactory performance was worse with increasing age (Figure 2). Overall, those less than the age of 70 had a mean identification score of 9.6 (SD = 2.4), whereas those 90 years of age or greater had a mean score of 6.9 (SD = 3.3). A decade increase in age was associated with a 22% reduction in the odds of meeting a given odor identification performance criterion (OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.66–0.93, Table 3, Model 3). Education, vascular disease burden, lifetime alcohol use, and income were not statistically significant in the final multivariate model, although higher income was associated with better olfactory performance before controlling for cognitive function (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results from ordinal logistic regression models fit to the number of odors identified correctly (range 0–12)

| Model 1 (n = 1002) | Model 2 (n = 1001) | Model 3 (n = 1001) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Age (per decade) | 0.57 | 0.48–0.67 | 0.60 | 0.51–0.71 | 0.78 | 0.66–0.93 |

| Men (vs. women) | 0.94 | 0.67–1.32 | 0.78 | 0.55–1.10 | 0.97 | 0.68–1.38 |

| Presence of depressive symptoms (vs. not) | 0.97 | 0.74–1.26 | 0.97 | 0.75–1.27 | 1.05 | 0.80–1.37 |

| Men × presence of depressive symptoms | 0.53 | 0.32–0.88 | 0.53 | 0.32–0.88 | 0.56 | 0.33–0.93 |

| Loneliness score (per 1 SD = 0.6) | 0.78 | 0.69–0.88 | 0.79 | 0.70–0.90 | 0.86 | 0.77–0.98 |

| Education | ||||||

| HS or less | Reference | 0.89–1.46 | Reference | 0.66–1.09 | ||

| >HS | 1.14 | 0.85 | ||||

| Income ($) | ||||||

| <25000 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 25000–49999 | 1.51 | 1.14–1.99 | 1.22 | 0.92–1.62 | ||

| 500000+ | 1.48 | 1.08–2.02 | 1.19 | 0.87–1.63 | ||

| Missing/unknown | 0.39 | 0.25–0.62 | 0.57 | 0.36–0.89 | ||

| Vascular disease (no. of conditions) | 1.02 | 0.85–1.24 | 1.04 | 0.86–1.25 | ||

| Vascular risk (no. of conditions) | 0.99 | 0.86–1.14 | 0.95 | 0.82–1.09 | ||

| Lifetime daily alcohol intake | 1.01 | 0.91–1.13 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | ||

| Global cognition score (per 1 SD = 0.6) | 2.15 | 1.86–2.50 | ||||

Mental health and olfactory performance

Loneliness

Increased feelings of loneliness were associated with decreased odor identification performance after controlling for age, sex, and depressive symptoms [OR (per 1 SD) = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.69–0.88; Table 3, Model 1] and remained significant after controlling for other potential confounders (Table 3, Model 2). Cognitive function was clearly associated with olfactory function. However, despite the further adjustment for global cognition, the relationship between loneliness and olfactory performance remained significant, albeit attenuated [OR (per 1 SD) = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.77–0.98; Table 3, Model 3].

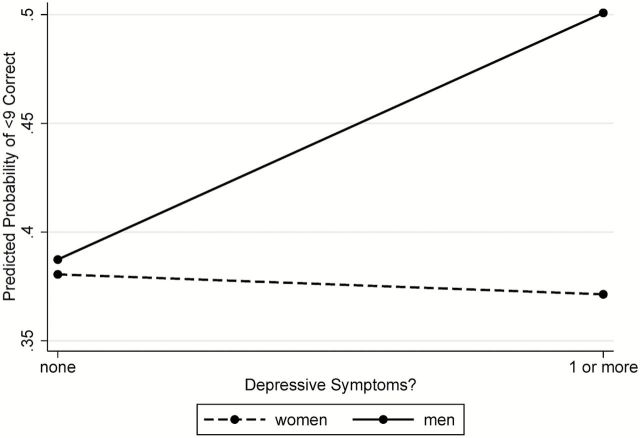

Depression

The association between depressive symptoms and olfactory performance consistently varied by sex across all models considered (P < 0.05 for the sex by depressive symptoms interaction) with men with depressive symptoms reporting worse olfaction compared with men without depressive symptoms. Specifically, among women, presence of depressive symptoms was not significantly associated with odor identification performance (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.80–1.37). By contrast, among men, presence of symptoms was associated with worse performance (OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.37–0.91) (Table 3, Model 3; Figure 3). The same pattern was observed using the depressive symptom score instead (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Probability of olfactory dysfunction (fewer than 9 odors correctly identified) stratified by gender and presence of depressive symptoms, using estimates from Table 3 (Model 3).

Sensitivity analyses

Finally, we repeated these analyses using linear regression to confirm the robustness of the result, finding similar results for depression (Table 4). Although the loneliness score was not statistically significant (using P < 0.05) in the linear regression model, the P value is 0.069 and the 95% CI is (−0.35 to 0.01) which suggests a relationship in the same direction as that found in the ordinal logistic regression model.

Table 4.

Results from linear regression models fit to the number of odors identified correctly (range 0–12)

| Model 1 (n = 1001) | Model 2 (n = 1001) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression coefficient | 95% CI | Regression coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Age (per decade) | −0.20 | −0.45 to 0.05 | ||

| Men | −0.10 | −0.60 to 0.40 | ||

| Presence of depressive symptoms (vs. not) | −0.01 | −0.40 to 0.38 | ||

| Men × presence of depressive symptoms | −0.78 | −1.51 to −0.05 | ||

| Loneliness score (per 1 SD = 0.6) | −0.16 | −0.34 to 0.01 | ||

| Education | ||||

| HS or less | Reference | −0.69 to 0.06 | ||

| >HS | −0.31 | |||

| Income ($) | ||||

| <25000 | Reference | |||

| 25000–49999 | 0.16 | −0.25 to 0.57 | ||

| 500000+ | 0.02 | −0.43 to 0.47 | ||

| Missing | −1.03 | −1.70 to −0.37 | ||

| Vascular disease (no. of conditions) | −0.05 | −0.32 to 0.22 | ||

| Vascular risk (no. of conditions) | 0.01 | −0.19 to 0.22 | ||

| Lifetime daily alcohol intake | −0.03 | −0.18 to 0.12 | ||

| Global cognition score (per 1 SD = 0.6) | 1.29 | 1.12 to 1.46 | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.31 |

| R-squared | 0.18 | 0.21 | ||

Quantification of the effect of cognition on odor identification

Better cognition was associated with better olfactory performance, with an increase of 1 SD in the global cognition score associated with a 115% increase in the odds of scoring 9 or above on the olfactory test [OR (per 1 SD) 2.15, 95% CI = 1.86–2.50]. This result is broadly consistent with our prior work (Pinto et al. 2014).

We found that 18% of the variability in odor identification was due to cognition alone (Table 4, Model 1), a fraction that increased to 21% in the full model (Table 4, Model 2). However, the association between olfaction and loneliness and depression remained robust after adjusting for cognitive function.

Discussion

We found an association between poor odor identification and increased symptoms of loneliness and depression (among men) in older adults. Cacioppo et al. (2009) has shown that loneliness has a number of major deleterious effects on health, including increased release of cortisol, compromise of the immune response, and even early risk of death. Therefore, our observation of a close connection between chemosensory function to mental health may have a large public health impact.

The prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in our study was high, nearly 40%, broadly consistent with other community-based studies (e.g., Beaver Dam, Skovde, the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project), albeit with different forms of testing (Brämerson et al. 2004; Schubert et al. 2012; Pinto et al. 2014). Demographic changes in the United States (and worldwide) ensure that this segment of the population is likely to grow rapidly in the next decades. Thus, olfactory deficits will cause a significant and increasing public health burden in the 21st century and their association with mental health conditions warrants attention from clinicians and researchers alike.

Previous studies have found that decreased olfactory function is related to lower quality of life (Pollatos et al. 2007; Gopinath et al. 2011), perhaps due to the inability to smell pleasurable odors. Clinically, olfaction plays an important hedonic role in daily life across a number of domains. We found worse olfactory performance in those with depressive symptoms for men but not women, potentially indicating that men are more dependent on chemosensation in order to experience pleasure. Alternatively, our findings may result from sex differences in brain structure and function differences in olfactory pathways, for example in the amygdala, a location linked to pleasure, memory, and olfaction (Hamann 2005). Further research is needed to investigate the mechanisms underlying our observations.

Our subjects’ CES-D scores were low, highlighting their relatively good mental health, and suggesting that the relationship between depression with olfaction operates outside of extremes of disease states. Poor olfaction may result in depression or depressive symptoms due to the consequences of decreased pleasure in life from this sensory deficit or olfaction may be a bellwether of central nervous system derangements such as depression itself. Prospective studies of olfaction are needed to answer this question of cause and effect.

Croy et al. suggested that social factors are associated with olfactory decline, thereby providing a theoretical basis for how loss of social communication via olfactory decline would be expected to cause loneliness, an idea that others have supported conceptually (Steinbach et al. 2008). Previous studies have noted that many older people struggle with feelings of helplessness, social isolation, and depression (Adams et al. 2004; Prieto-Flores et al. 2011; Bekhet and Zauszniewski 2012). Interestingly, loneliness and depression tend to be moderately correlated (though the associations with olfaction are independent in our analyses) (Brämerson 2007). Finally, olfaction has been associated with behaviors such as attention to stimuli, social participation, and sexual activity in both young and older adults (Jacob and McClintock 2000; McClintock et al. 2005; Kern and McClintock 2011; Kern et al. 2014). Olfactory dysfunction may serve as a marker of central deficits in some component of social functioning, consistent with olfaction as a bellwether of neuropsychiatric function. Olfaction may also predict the development of loneliness by diminishing interest in and reward of social interactions. For example, during meals, which require intact olfaction to enjoy and which, are hubs of interaction. Finally, loneliness has been associated with diminished activation of the reward circuitry (in the ventral striatum) in response to pleasant social stimuli (Cacioppo et al. 2009). Olfaction, too, has been associated with reward and motivational centers in the brain, at least in animals (Fitzgerald et al. 2014), providing a potential anatomic connection linking these phenomena. These ideas remain to be tested in future work.

We found no evidence that cognition confounded these associations. This is notable because the task of odor identification contains a cognitive component (Finkel et al. 2001; Wilson et al. 2008; Schubert et al. 2013). Using the detailed cognitive battery in MAP, we found that cognition accounts for about a fifth of the variation in odor identification, but our associations with depression and loneliness remained intact after adjustment.

Our study had a number of strengths. The sample size of community-dwelling older persons on whom detailed cognitive and psychological variables as well as odor identification were available was relatively large. This allowed us to examine associations between odor identification and relatively novel variables. The main limitation is the cross-sectional analyses. This limits inferences regarding causality. Future investigation with longitudinal data is needed for stronger causal inferences.

Addressing the depression and loneliness that are associated with olfactory loss may help improve quality of life as patients deal with this burdensome sensory deficit. Often times, patients are embarrassed to admit concerns because they do not want to be targeted as being helpless (Bekhet and Zauszniewski 2012). Addressing depressive symptoms and loneliness, which have important effects on health overall, is important in providing holistic geriatric care. In parallel, it is essential to develop ways to allow patients to feel comfortable admitting to difficulties with olfactory performance (LaMendola 2012).

In short, our results provide additional support for the idea that smell is critical for pleasurable social activity and happiness in life (Griep et al. 2000; Miwa et al. 2001; Temmel et al. 2002; Hummel and Nordin 2005).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K23 AG036762 and R01AG17917), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (U01AI106683, Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program ([CRISP]), the McHugh Otolaryngology Research Fund, The Center on the Demography and Economics of Aging at The University of Chicago, and the Institute of Translational Medicine at The University of Chicago (KL2RR025000 and UL1RR024999). No funding bodies had any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Jamie M. Phillips and James Lane provided logistical support. We thank Robert M. Naclerio, MD, Fuad M. Baroody, MD (both Section of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery), and Louise C. Hawkley, PhD (NORC) at The University of Chicago for useful editorial comments provided generously. We gratefully acknowledge the participation of the MAP participants. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adams KB, Sanders S, Auth EA. 2004. Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: risk and resilience factors. Aging Ment Health. 8(6):475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. 1994. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med. 10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet AK, Zauszniewski JA. 2012. Mental health of elders in retirement communities: is loneliness a key factor? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 26(3):214–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Boyle PA, Wilson RS. 2012. Overview and findings from the Rush Memory and Aging Project. Curr Alzheimer Res. 9:648–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Aggarwal NT, Arvanitakis Z, Kelly J, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. 2005. Parkinsonian signs in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 65(12):1901–1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brämerson A, Johansson L, Ek L, Nordin S, Bende M. 2004. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction: the skövde population-based study. Laryngoscope. 114(4):733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brämerson A, Nordin S, Bende M. 2007. Clinical experience with patients with olfactory complaints, and their quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 127(2):167–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Norris CJ, Decety J, Monteleone G, Nusbaum H. 2009. In the eye of the beholder: individual differences in perceived social isolation predict regional brain activation to social stimuli. J Cogn Neurosci. 21(1):83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T. 2014. Olfactory disorders and quality of life—an updated review. Chem Senses. 39(3):185–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Symmank A, Schellong J, Hummel C, Gerber J, Joraschky P, Hummel T. 2014. Olfaction as a marker for depression in humans. J Affect Disord. 160:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Gierveld J. 1987. Developing and testing a model of loneliness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 53(1):119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuis F. 1985. The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Meas. 9:289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Deems DA, Doty RL, Settle RG, Moore-Gillon V, Shaman P, Mester AF, Kimmelman CP, Brightman VJ, Snow JB., Jr 1991. Smell and taste disorders, a study of 750 patients from the University of Pennsylvania Smell and Taste Center. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 117(5):519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL. 2015. Handbook of olfaction and gustation. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Frye RE, Agrawal U. 1989. Internal consistency reliability of the fractionated and whole University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Percept Psychophys. 45(5):381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Marcus A, Lee WW. 1996. Development of the 12-item Cross-Cultural Smell Identification Test (CC-SIT). Laryngoscope. 106(3 Pt 1):353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. 1984. Development of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 32(3):489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel D, Pedersen NL, Larsson M. 2001. Olfactory functioning and cognitive abilities: a twin study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 56(4):P226–P233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald BJ, Richardson K, Wesson DW. 2014. Olfactory tubercle stimulation alters odor preference behavior and recruits forebrain reward and motivational centers. Front Behav Neurosci. 8:81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath B, Anstey KJ, Sue CM, Kifley A, Mitchell P. 2011. Olfactory impairment in older adults is associated with depressive symptoms and poorer quality of life scores. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 19(9):830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griep MI, Mets TF, Collys K, Ponjaert-Kristoffersen I, Massart DL. 2000. Risk of malnutrition in retirement homes elderly persons measured by the “mini-nutritional assessment”. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 55(2):M57–M63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann S. 2005. Sex differences in the responses of the human amygdala. Neuroscientist. 11(4):288–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HJ, Ishii EK, Macturk RH. 1998. Age-related changes in the prevalence of smell/taste problems among the United States adult population: results of the 1994 disability supplement to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 855(1):716–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Nordin S. 2005. Olfactory disorders and their consequences for quality of life. Acta Otolaryngol. 125(2):116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. 1999. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 159(15):1701–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S, McClintock MK. 2000. Psychological state and mood effects of steroidal chemosignals in women and men. Horm Behav. 37(1):57–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern DW, McClintock MK. 2011, April 16. Is androstadienone a social odor in older adults? Thresholds and attention to emotional stimuli. Association for Chemoreceptive Sciences. 305. [Google Scholar]

- Kern DW, Schumm LP, Wroblewski KE, Pinto JM, McClintock M. 2014. Ability to detect androstadienone is associated with sexual and social behavior in older adults in the United States. Association for Chemoreceptive Sciences Annual Meeting, Poster 283, presented April 9, 2014, Bonita Springs, FL. Available from http://www.achems.org/files/2014%20Annual%20Meeting/FINAL%202014%20AChemS%20Program.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. 1993. Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. J Aging Health. 5:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMendola J. 2012, August 6. Anosmia. Available from http://www.nytimes.com/video/opinion/100000001700730/anosmia.html [Google Scholar]

- McClintock MK, Bullivant S, Jacob S, Spencer N, Zelano B, Ober C. 2005. Human body scents: conscious perceptions and biological effects. Chem Senses. 30(Suppl 1):i135–i137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Anton HA, Townson AF. 2008. Measurement properties of the CESD scale among individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 46(4):287–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T, Furukawa M, Tsukatani T, Costanzo RM, DiNardo LJ, Reiter ER. 2001. Impact of olfactory impairment on quality of life and disability. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 127(5):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy C, Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Nondahl DM. 2002. Prevalence of olfactory impairment in older adults. JAMA. 288(18):2307–2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naudin M, El-Hage W, Gomes M, Gaillard P, Belzung C, Atanasova B. 2012. State and trait olfactory markers of major depression. PLoS One. 7(10):e46938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JP, Wroblewski K., Kern D, Schumm LP, McClintock MK. 2014. Olfactory dysfunction predicts 5-year mortality in older adults. PLoS One. 9(10):e107541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollatos O, Albrecht J, Kopietz R, Linn J, Schoepf V, Kleemann AM, Schreder T, Schandry R, Wiesmann M. 2007. Reduced olfactory sensitivity in subjects with depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 102(1–3):101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Flores ME, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Forjaz MJ, Rojo-Perez F, Martinez-Martin P. 2011. Residential satisfaction, sense of belonging and loneliness among older adults living in the community and in care facilities. Health Place. 17(6):1183–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, Huang GH, Klein BE, Klein R, Pankow JS, Nondahl DM. 2012. Olfactory impairment in an adult population: the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Chem Senses. 37(4):325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert CR, Cruickshanks KJ, Fischer ME, Huang GH, Klein R, Pankratz N, Zhong W, Nondahl DM. 2013. Odor identification and cognitive function in the Beaver Dam Offspring Study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 35(7):669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach S, Staudenmaier R, Hummel T, Arnold W. 2008. Loss of olfaction with aging: a frequent disorder receiving little attention. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 41(5):394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmel AF, Quint C, Schickinger-Fischer B, Klimek L, Stoller E, Hummel T. 2002. Characteristics of olfactory disorders in relation to major causes of olfactory loss. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 128(6):635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Buchman AS, Tang Y, Bennett DA. 2008. Odor identification and progression of parkinsonian signs in older persons. Exp Aging Res. 34(3):173–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Bennett DA. 2006. Odor identification and decline in different cognitive domains in old age. Neuroepidemiology. 26(2):61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, Schneider JA, Kelly JF, Barnes LL, Tang Y, Bennett DA. 2007. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 64(2):234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki CJ, Gilbert AN. 1989. National Geographic Smell Survey: effects of age are heterogenous. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 561(1):12–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]