Abstract

Objectives:

Epilepsy is very common in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, occurring in 6.54 out of every 1000 individuals. The current study was conducted to determine the level of public awareness of and attitudes toward epilepsy in the city of Majmaah, Saudi Arabia.

Subjects and Methods:

This descriptive study was conducted in Majmaah, Saudi Arabia. The study population included respondents derived from preselected public places in the city. Stratified random sampling was used, and the sample size was made up of 706 individuals. A structured questionnaire was used for data collection from respondents after receiving their verbal consent. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 2.0. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Majmaah University.

Results:

The results showed that 575 (81.4%) of the respondents had heard or read about epilepsy. Almost 50% of the respondents knew someone who had epilepsy, and 393 (55.7%) had witnessed what they believed to be a seizure. Results showed that 555 (78.6%) respondents believed that epilepsy was neither a contagious disease nor a type of insanity. It was found that 335 (47.5%) stated that epilepsy was a brain disease, and almost one-quarter of the respondents said that the manifestation of an epileptic episode is a convulsion. Regarding attitude, 49% and 47.3% of respondents stated that they would not allow their children to interact with individuals with epilepsy and would object to marrying an individual with epilepsy, respectively.

Conclusion:

Although knowledge about epilepsy is improving, it is still not adequate. The study showed that the attitude toward epilepsy is poor.

Keywords: Attitudes, epilepsy, knowledge, Majmaah, Saudi Arabia, Saudi population

Introduction

Epilepsy is the most common neurological disorder, affecting more than 50 million people worldwide.[1] In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, epilepsy occurs in 6.54 out of every 1000 individuals.[2]

Like in other parts of the world, in the Arabian Peninsula, epilepsy is still surrounded by many myths, misbeliefs, and stigmas.[3] There are two main methods to reduce these false beliefs and attitudes toward epilepsy: Improving treatment and changing the public's opinion and attitude toward this disorder using information campaigns.[4] Surveys on public awareness, attitude, and knowledge of epilepsy are useful in decreasing these discriminatory behaviors and false beliefs and ideas.[5]

Sometimes, the social discrimination against people with epilepsy is more serious than the disease itself. Adults with epilepsy usually have problems with acceptance in the community, in terms of gaining admission to a good institute and access to public residences. This disease may cause loss of employment and difficulty with getting married.[6]

One study, conducted in Saudi Arabia with 398 participants, showed that most of the Saudi population still believes that Fairy (Jinn) possession is a cause for epilepsy.[1,7] It is the basic responsibility of all health professionals to try to improve their patients’ quality of life, which involves not only controlling the disease itself but also changing these beliefs and the stigma associated with the disease with a planned and scientific approach.[7] Many studies on public awareness of and attitude toward epilepsy have been conducted in different countries including Jordan,[8] the United States,[9] China,[10] Austria,[11] Italy,[12] Istanbul,[13] Greece,[14] New Zealand,[15] Kuwait,[16] and the United Arab Emirates.[17] In Saudi Arabia, it has been studied in Riyadh[1] and Jeddah[18] – but in other Saudi Arabian cities, no formal study has been conducted to examine the attitude toward and awareness of epilepsy.

The objectives of the present study were to assess the knowledge and level of public awareness within the general population living in Majmaah regarding epilepsy and attitudes and practices toward individuals with epilepsy and to compare these results with the findings from Riyadh.

Subjects and Methods

This was a facility-based, descriptive study conducted in the city of Majmaah. Majmaah is the capital of Majmaah province, located about 180 km North of the capital city of Riyadh. The population is about 60,000. The study population included respondents derived from preselected public places in the city. The population included Majmaah University students, health personnel from the health facilities in Majmaah, and people attending selected markets in the city. Stratified random sampling was employed in this study. The sample size was selected according to the following formula:

Z2 × pq/d2

Z = standard normal deviate = 1.96

p = prevalence = 0.3

q = 1 − p

d = accepted error = 0.05

The sample size was calculated as 768.[19]

A structured, pretested questionnaire that contained sociodemographic items, as well as items regarding knowledge of and attitudes toward epilepsy, was used for data collection. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 2.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used to analyze the data.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Majmaah University.

Verbal consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the purpose and outcome of the study. All data and information will be kept confidential and used only for the aims of this study.

Results

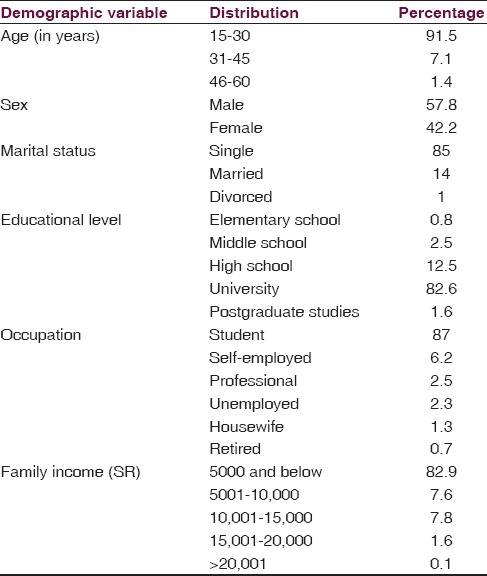

Data were collected from 706 respondents with a response rate of 92%. Out of these 706 respondents, 408 (57.8%) were males and 298 (42.2%) were females. A majority of the respondents, 583 (82.6%), had a higher degree of education. The sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics of study sample (n=706)

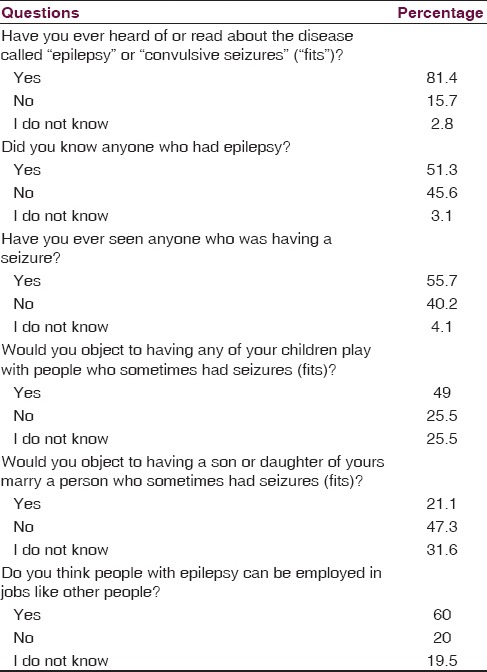

Respondents were asked about questions related to their familiarity with, attitude toward, and understanding of epilepsy. We found that 575 (81.4%) had heard or read about epilepsy [Tables 2–5]. Almost 50% of the respondents knew someone who had epilepsy, and 393 (55.7%) had witnessed what they believed to be a seizure. Moreover, 346 (49%) respondents said that would not allow their children to interact with individuals with epilepsy; furthermore, 334 (47.3%) said that they would object to marrying an individual with epilepsy. When asked if individuals with epilepsy should have the same employment opportunities as the general population, 141 (20%) respondents said they should not, whereas 427 (60.5%) said they should.

Table 2.

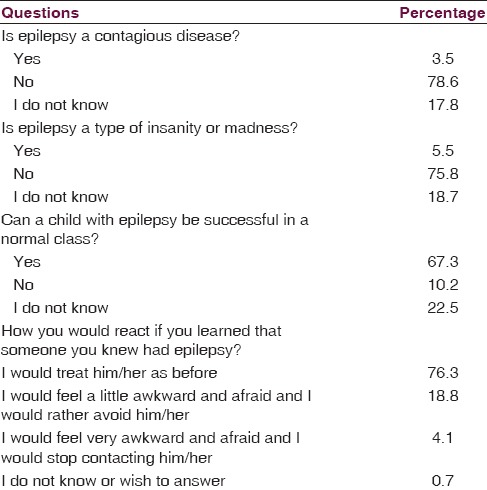

Percentage of responses to questions regarding familiarity with, attitude toward, and understanding of epilepsy (n=706)

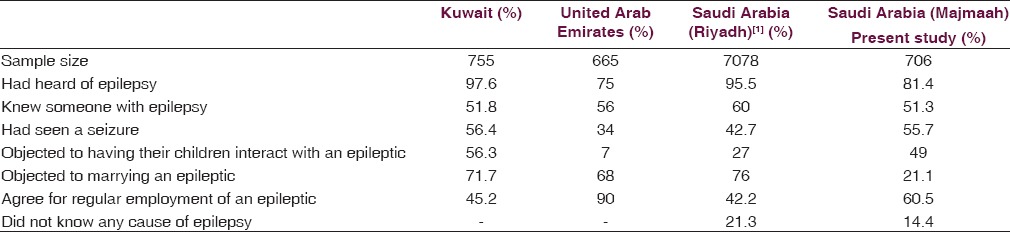

Table 5.

Comparison of the present study on public awareness and attitudes toward epilepsy with similar studies in the Arabian Gulf

Table 3.

Attitude toward epilepsy (%) (n=706)

Table 4.

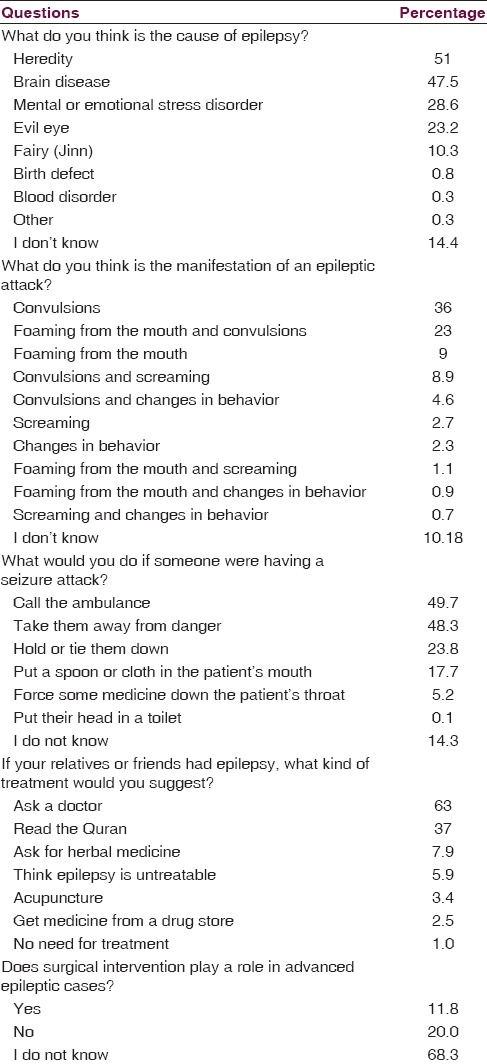

Knowledge and practices toward epilepsy (%) (n=706)

They were also asked about their attitude toward epilepsy. A majority of the respondents, 555 (78.6%), believed that epilepsy was neither a contagious disease nor a type of insanity. However, almost 10.2% said that a child with epilepsy could not be successful in school. When respondents were asked how they would react if they discovered that someone they knew had epilepsy, 539 (76.3%) reported that they would treat them the same as they did before, whereas 133 (18.8%) reported that they would feel a little awkward and afraid and that they would rather avoid the person. Regarding social relationships with an individual with epilepsy, 506 (71.7%) respondents said they would become close friends with an individual with epilepsy.

With regard to the respondents’ knowledge of epilepsy, a majority of them (335, or 47.5%) said that it is a brain disease, and almost one-quarter of respondents said that the manifestation of an epileptic episode is a convulsion. When asked about the appropriate actions to take if someone had an epileptic attack, almost half of the respondents - 341, or 48.3% - said that they would take the person away from danger. The other responses included forcing medicine down the person's throat (5.2%), putting a spoon or cloth in the patient's mouth (17.7%), holding or tying them down (23.8%), and putting their head in a toilet (0.1%). When respondents were asked about what kind of treatment they would suggest for an individual with epilepsy, most of the respondents - 445, or 63% - said that they would seek medical advice from a doctor. Regarding the role of surgical intervention for epileptic cases, 482 (68.3%) do not know about it.

Discussion

This study, performed in Majmaah, Saudi Arabia, was similar to a study conducted in Riyadh. Our participants responded regarding their familiarity with, attitude toward, and understanding of epilepsy including their attitude regarding their children's interactions with someone who had epilepsy and whether they would marry someone with epilepsy and the knowledge and practices toward epilepsy and agreement for regular employment of an epileptic. We also compared our results with similar international studies and with the study conducted in Riyadh.

Our study differs from already published studies in Riyadh and other parts of the world in terms of the number of respondents, their education level, and their ages. Majmaah is a small city with comparatively fewer opportunities for education as compared to Riyadh; it also has fewer expats with the local population. Our respondents were university students who represented the educated population of the country - this was in contrast with other studies conducted on the general population, which respondents from all age groups and education levels.

Basic knowledge regarding epilepsy was comparatively less in Riyadh (81.4% vs. 95.5%), but most respondents reported that they had witnessed an epileptic fit (55.7% vs. 42.7%). This is similar to many countries such as Italy and Kuwait, but better than results from the UAE. Majmaah is a small city with limited and close social life compared to Riyadh. This may be the reason that more respondents had witnessed more epileptic fits.

Forty-nine percent said that they do not allow their children to play with someone with epilepsy; this number is almost double what was found in Riyadh (49% vs. 27%). This response shows the extent of the discrimination and stigma that surrounds epilepsy. These sociocultural issues are important determinants of epilepsy's clinical course and often limit appropriate treatment.[20]

Regarding their attitude toward epilepsy, a majority of respondents agreed that epilepsy was not a contagious disease, which is very close to what was found in Riyadh (78% vs. 84.8%). About 475 (67.3%) respondents believed that students with epilepsy could be successful, and 539 (76.3%) were believed that there is no harm in becoming a friend with an epileptic patient. Still, 10% believed that Jinn “fairy” was responsible for epilepsy, and 23% believed that this was Evil Eye. Despite the improvement in the awareness of epilepsy and the attitudes of the public toward the disease in Saudi Arabia, some still think it is linked to evil spirits; thus, spiritual rituals and religious healing are commonly believed to be effective treatments.[21]

In contrast to the study in Riyadh, only 21% of respondents said that they would not allow their children to marry someone with epilepsy (21% vs. 76%). In the traditional family structure, the decision to marry is made mainly by both families. Although fathers are believed to play a major role in the decision-making process when it comes to marriage, mothers actually contribute a greater role, and they are considered to be the more influential albeit silent, decision makers. As marriage is usually arranged by the parents, the choice of a partner usually reflects the values of the parents.[22]

Regarding epilepsy treatment, 63% of respondents said that epileptics need medical treatment (vs. 49.4% in the Riyadh study), whereas 5.9% believed that epilepsy was untreatable (vs. 16.2%). Meanwhile, 11.8% believed that surgery has a role in treating epilepsy (vs. 7.4%). Overall, these are better responses than those found in Riyadh. Our results show that, when it comes to epilepsy, the knowledge and behavior of the Saudi public are showing some improvements – a similar finding compared to another study done by Muthaffar and Jan.[23]

Our study was followed by an awareness campaign in Majmaah to increase the level of awareness of, and correct misunderstandings about, the disease of epilepsy.

Conclusion

Although knowledge of – and the public's perception toward – epilepsy is improving, cultural and social beliefs regarding the disease still persist. These values inhibit the community from accepting people with epilepsy in their close social circles. A massive educational campaign that involves all the stakeholders of society, including health-care providers and prominent community members, should be undertaken to make society more tolerant when it comes to epilepsy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the people and students who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Alaqeel A, Sabbagh AJ. Epilepsy; what do Saudi's living in Riyadh know? Seizure. 2013;22:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Rajeh S, Awada A, Bademosi O, Ogunniyi A. The prevalence of epilepsy and other seizure disorders in an Arab population: A community-based study. Seizure. 2001;10:410–4. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2001.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masri A, Yasein N, Barghouti F, Al-Qudah AA. Familiarity, knowledge, and attitudes towards epilepsy among attendees of a family clinic in Amman, Jordan. Neurosci. 2008;13:53–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghanean H, Nojomi M, Jacobsson L. Public awareness and attitudes towards epilepsy in Tehran, Iran. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:21618. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.21618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong V, Chung B, Wong R. Pilot survey of public awareness, attitudes and understanding towards epilepsy in Hong Kong. Neurol Asia. 2004;9:21–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.510023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dantas FG, Cariri GA, Cariri GA, Ribeiro Filho AR. Knowledge and attitudes toward epilepsy among primary, secondary and tertiary level teachers. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59:712–6. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2001000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed M. Epilepsy: Stigma and management. Curr Res Neurosci. 2011:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daoud A, Al-Safi S, Otoom S, Wahba L, Alkofahi A. Public knowledge and attitudes towards epilepsy in Jordan. Seizure. 2007;16:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caveness WF, Merritt HH, Gallup GH., Jr A survey of public attitudes toward epilepsy in 1974 with an indication of trends over the past twenty-five years. Epilepsia. 1974;15:523–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1974.tb04026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai CW, Huang XS, Lai YH, Zhang ZQ, Liu GJ, Yang MZ. Survey of public awareness, understanding, and attitudes toward epilepsy in Henan province, China. Epilepsia. 1990;31:182–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.1990.tb06304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spatt J, Bauer G, Baumgartner C, Feucht M, Graf M, Mamoli B, et al. Predictors for negative attitudes toward subjects with epilepsy: A representative survey in the general public in Austria. Epilepsia. 2005;46:736–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.52404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canger R, Cornaggia C. Public attitudes toward epilepsy in Italy: Results of a survey and comparison with U.S.A and West German data. Epilepsia. 1985;26:221–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1985.tb05409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekiroglu N, Ozkan R, Gürses C, Arpaci B, Dervent A. A study on awareness and attitude of teachers on epilepsy in Istanbul. Seizure. 2004;13:517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diamantopoulos N, Kaleyias J, Tzoufi M, Kotsalis C. A survey of public awareness, understanding, and attitudes toward epilepsy in Greece. Epilepsia. 2006;47:2154–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hills MD, MacKenzie HC. New Zealand community attitudes toward people with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1583–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.32002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awad A, Sarkhoo F. Public knowledge and attitudes toward epilepsy in Kuwait. Epilepsia. 2008;49:564–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bener A, al-Marzooqi FH, Sztriha L. Public awareness and attitudes towards epilepsy in the United Arab Emirates. Seizure. 1998;7:219–22. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(98)80039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haneef DF, Abdulqayoum HA. Epilepsy: Knowledge, attitude and awareness in Jeddah Saudi Arabia. BMC Genomics. 2014;15(Suppl 2):P61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986. World Health Organization. Sample Size Determination; User Manual. Epidemiological and Statistical Methodology Unit. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cairo, EG: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean Region; 2010. World Health Organization. Epilepsy in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: Bridging the Gap. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan SA. Epilepsy awareness in Saudi Arabia. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2015;20:205–6. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2015.3.20150338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehndiratta MM, Paul B, Mehndiratta P. Arranged marriage, consanguinity and epilepsy. Neurol Asia. 2007;12:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthaffar OY, Jan MM. Public awareness and attitudes toward epilepsy in Saudi Arabia is improving. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2014;19:124–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]