Abstract

Background:

Baseline stroke knowledge in a targeted population is indispensable to promote the effective stroke education. We report the baseline knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of high school students with respect to stroke from Nepal.

Materials and Methods:

A self-structured questionnaire survey regarding KAP about stroke was conducted in high school students of 33 schools of Bharatpur, Nepal. Descriptive statistics including Chi-square test was used, and the significant variables were subjected to binary logistic regression.

Results:

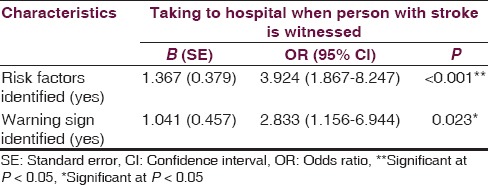

Among 1360 participants, 71.1% had heard or read about stroke; 30.2% knew someone with stroke. 39.3% identified brain as the organ affected. Sudden onset limb/s weakness/numbness (72%) and hypertension (74%) were common warning symptom and risk factor identified. 88.9% would take stroke patients to a hospital. Almost half participants (55.5%) felt ayurvedic treatment be effective. 44.8% felt stroke as a hindrance to a happy life and 86.3% believed that family care was helpful for early recovery. Students who identified at least one risk factor were 3.924 times (P < 0.001, confidence interval [CI] = 1.867–8.247) or those who identified at least one warning symptom were 2.833 times (P ≤ 0.023, CI = 1.156–6.944) more likely to take stroke patients to a hospital.

Conclusion:

KAP of high school Nepalese students regarding stroke was satisfactory, and the students having knowledge about the risk factors and warning symptoms were more likely to take stroke patients to a hospital. However, a few misconceptions persisted.

Keywords: Attitude, knowledge, Nepal, practice, stroke, students

Introduction

The study to survey the baseline conditions for stroke knowledge in a targeted population is indispensable to promote the effective stroke education. Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and the leading cause of long-term disability in high-income countries.[1] In Nepal, it is estimated that 50,000 people per year are afflicted with stroke, with 15,000 annual deaths;[2] stroke is among the top five common diseases.[3] Stroke has a tremendous economic burden for the family members and also for the society;[3,4] however, Nepal has the lowest gross domestic product per capita among all South Asian countries and lower than its neighbor.[5] Timely hospital presentation and improved control of risk factors for stroke have a great impact on stroke prevention and treatment.[6,7] Unfortunately, many stroke patients arrive late at the hospital due to lack of knowledge about stroke[8] and its symptoms.[9] Reduction of time from stroke onset to hospital presentation and risk reduction rely on the stroke knowledge of both patients and their family members including the general population.[9,10,11]

A more widespread school education program is required to improve the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of students regarding stroke, which in turn might improve the control of risk factor(s), treatment and outcomes, by early hospital presentation in the near future. Understanding baseline KAP with respect to stroke is one of the essential early steps for evolving educational strategies in these populations. Moreover, stroke education for the youth would be a promising mean to spread stroke knowledge widely.[12] We studied KAP regarding stroke among high school Nepalese students for the first time in Nepal.

Materials and Methods

This school-based survey was conducted in high school students (class 9 and 10) of 33 private schools of Bharatpur, Chitwan district, Central Southern Nepal, from June 1, 2013, to July 20, 2013. A self-structure questionnaire consisting of 15 questions was developed by a group of medical professionals (nurses and doctors trained by a neurologist). The questions were designed to cover KAP with respect to stroke and had “yes” or “no” responses. After obtaining permission from the school, the pretested questionnaire was distributed to students by a group of medical professionals who developed the questionnaire. Students were preinstructed not to discuss any question before the completion of the study and it was monitored. No attempt was made to prompt the student by suggesting answers.

All statistical analysis was performed using (IBM SPSS, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY, USA). The analysis was started with descriptive statistics. Chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between demographic variables (age, gender, religion, and family history of stroke) and risk factor; demographic variables and warning sign response as choosing to take a stroke patient to a hospital and demographic variables; hospital taking response and risk factors; and hospital taking response and warning sign. Knowledge of stroke risk factors and warning signs were taken as the indicator of stroke knowledge. All the demographic variables for association analysis were converted into dichotomous. The response of stroke knowledge was either “Yes” (identified ≥1 risk factors or warning symptoms) or “No.” The response of stroke first aid practice was either choosing to take a stroke patient to a hospital (Yes) or not choosing (No). Those variables, which were significant with the response as taking a patient to a hospital, were subjected to binary logistic regression analysis. In all the analysis, P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant value.

Results

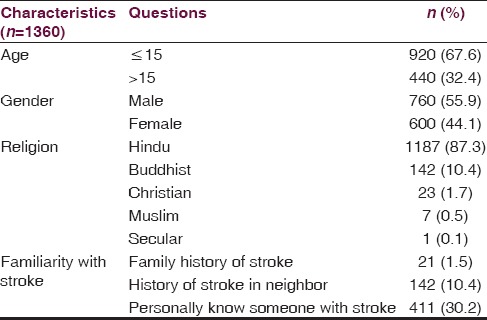

A total of 1360 students completed the questionnaire. The majority were boys (55.9%). Most students were Hindu (87.3%) followed by Buddhist (10.4%). About 1.5% of students had someone with stroke in their family, 10.4% of students had someone with stroke in their neighborhood, and 30.2% personally knew someone with stroke [Table 1].

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of the participants

More than two-third of the students (71.1%) had heard or read about stroke. Stroke was identified as a brain disorder by 535 (39.3%) students, and 1 out of 4 (25.2%) students believed that stroke is a disease of an elderly. A few misconceptions were prevalent among the students, including the beliefs that stroke is a contagious disease (7.4%) and the result of an ancestors’ sin (10.3%). Most of the students (78.5%) thought that the stroke could be treated and prevented (82.5%). However, 755 (55.5%) students felt that ayurvedic treatment is effective. Stroke was felt as a hindrance to a happy life by 609 (44.8%) students. However, 1174 (86.3%) students believed that family care is helpful for early recovery. Almost 1209 (88.9%) students would take a stroke patient to a hospital in an emergency, nearly a quarter of students (24.1%) would sprinkle water over the face of a person having a stroke, and 182 (13.4%) would wait for spontaneous recovery. Most students identified high blood pressure (74%) as a risk factor of a stroke followed by excess alcohol consumption (41.2%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Responses of 1360 high school students of Grade 9 and 10 to the selected knowledge, attitude, and practice question

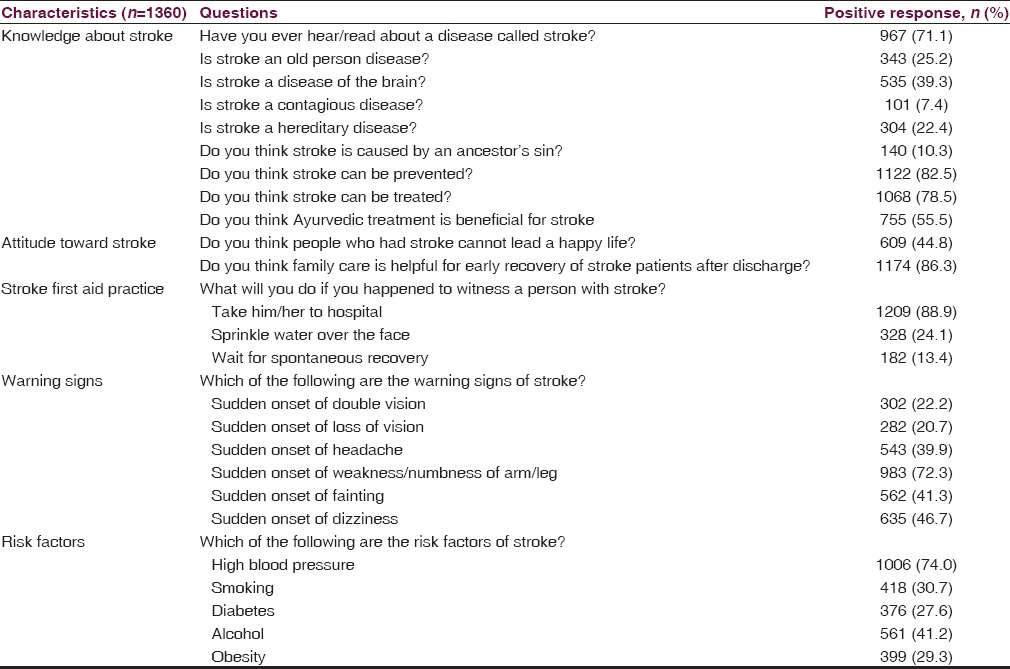

Most of them identified ≥ 1 risk factor (96.1%) while only 6.6% identified all the provided risk factors and few of them did not identify any risk factor (3.9%) [Table 3]. Similarly, sudden onset of weakness/numbness of limbs (72.3%) and sudden onset of dizziness (46.7%) were the most commonly identified warning sign/symptoms [Table 2]. The majority (97.5%) identified at least one symptom about 5.2% could identify all the provided warning symptoms while 2.5% identify none of the warning sign [Table 3].

Table 3.

Number of risk factors and warning signs of stroke identified by the high school students

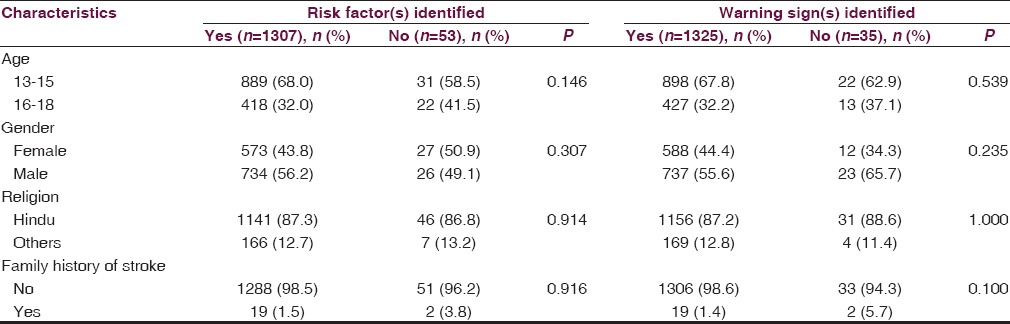

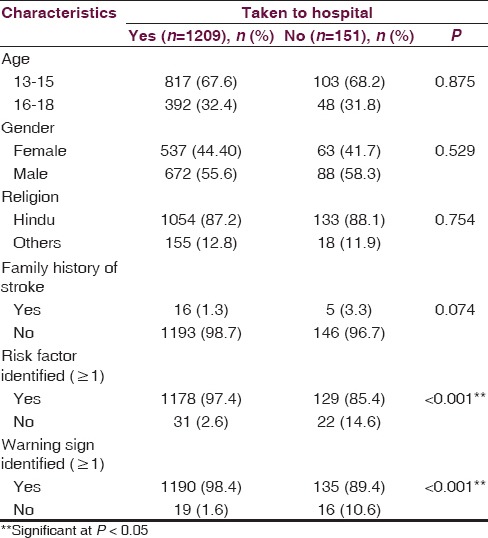

The Chi-square test showed no significant association of age, gender, religion, and family history of stroke with risk factor (s) identified and warning symptoms identified [Table 4]. However, there was a significant association of response choosing to take a patient to a hospital (if they witness him/her with stroke) with risk factors identified (P < 0.001) and warning symptoms identified (P < 0.001) [Table 5]. The binary logistic regression analysis showed that identification of at least one risk factor (P < 0.001, odds ratio [OR] [confidence interval (CI)] = 3.924 [1.867–8.247]) and identification of at least one warning symptoms (P ≤ 0.023, OR [CI] = 2.833 [1.156–6.944]) are good predictors of response choosing to take a patient to a hospital [Table 6].

Table 4.

Association of risk factors and warning signs of stroke with sociodemographic factors

Table 5.

Association of response of the students taking a person to hospital (if they witness him/her with stroke) with sociodemographic variables, risk factors identified, and warning sign identified

Table 6.

Binary logistic regression of response of students taking a person to hospital (if they witness a person with stroke) with selected variables

Discussion

This school-based survey indicates good knowledge of risk factors and warning sign, attitude, and practice with respect to stroke. More than two-thirds of students had heard or read about stroke, and one-third personally knew someone with stroke. Such high degree of an acquaintance of stroke in developing countries like Nepal may be related to closer interpersonal and interfamily relationships in these regions.

There was no significant association between gender and knowledge of risk factors or warning signs; however, boys identified risk factor and warning sign more than girls. Some studies have also revealed no significant difference in knowledge by gender.[13,14] Our study was done in students with similar education level which might have contributed to a nonsignificant association. This shows that they do not possibly receive additional knowledge about stroke other than school and any intervention about providing information about stroke might increase the knowledge, change the attitude, and practice regarding stroke. In contrast, a systematic review from a gender perspective concludes that women had better knowledge of stroke risk factor and its warning sign as compared to men.[15] Moreover, women showed a better stroke knowledge and also a better gain of information after stroke-related educational campaign in Germany.[16]

Having a family history of stroke was not associated with having knowledge about stroke risk factors or warning signs. A study done in “stroke belt” of Alabama, showed that having a family history of stroke did not drive perceived stroke risk, risk factor control, or intentions to exercise in young to the middle-aged population.[17] This urged health care providers to educate people about the family history of stroke as a significant risk factor and promote healthy lifestyle interventions. In contrast, some studies have observed better knowledge in people with family history of stroke.[18,19]

About two-thirds of the students did not recognize stroke to be a disease of the brain. Similar results were obtained in Northwest India which is closer to the border of Nepal.[20] In contrast, a study in the Australian urban population showed 73% respondent correctly identified brain as the target organ of stroke.[19] Moreover, a few misconceptions about the cause of stroke were prevalent in our study. About one-quarter of students believed stroke to be a hereditary disease and even few believed stroke to be a contagious disease or an ancestors’ sin. These indicate that Nepal needs to promote educational program about stroke to improve the knowledge of its population and to come out of the prevailing misconception.

Three out of four students (74%) identified high blood pressure to be a risk factor for stroke. Alcohol and smoking were the subsequent risk factors identified. A higher proportion of students (96.1%) identified ≥1 risk factor, 32.7% suggested ≥3 risk factors, and 6.6% identified all of the given risk factors. Interestingly, about three-fourth students (72%) believed that stroke can present with sudden weakness or numbness of limbs. The majority of the students (97.5%) correctly identified, at least, one symptom, 44.8% identified three or more symptoms and 5.2% identified all of them. Results obtained in our study were in concordance to that in Northwest India.[19] In this study, hypertension was the most common risk factor and paralysis of one side of the body was the most common suggested warning symptom but 71% could identify ≥1 risk factors and only 13% identified ≥3 risk factors, whereas 71% identified ≥1 symptoms, 8% listed ≥3 symptoms. The better results in our study as compared to this study may be due to the difference in the educational level of the sample population as about half of the subjects in the study in Northwest India had a lower educational level (illiterate and primary) while our study group consisted of students in secondary level. Another study in Australian urban population, the most common risk factor identified was smoking, followed by stress, and the most common warning sign described was a blurred and double vision or loss of vision. About 76.2% listed ≥1 risk factors, but only 49.8% suggested ≥1 warning signs.[19] Similarly, in a population-based national survey in Korea, hypertension was the most common risk factor and paresis was the most common symptom listed. In the study, 56% listed ≥1 risk factors and 62% listed ≥1 symptoms.[21] The knowledge about risk factor and the warning sign of stroke varies, but it suggests a need for the overall improvement of the existing knowledge and not only a particular risk factor or warning sign.

More than two-third of students believed stroke can be treated and more than four-fifth students believed stroke can be prevented. However, more than half students believed ayurvedic medication could treat stroke. It can be due to much influence of ayurvedic medication in developing countries like Nepal.[22]

About 45% students believed stroke could be a hindrance to the happy life. It may be due to their lack of knowledge about thrombolytic treatment, interventional therapy, rehabilitation, and physiotherapy. Recent years have seen giant leaps in the science of rehabilitation in stroke,[23] but unfortunately, this is practiced less in Nepal and the services are centered mostly in the capital. However, 86% believed that the family care is helpful for discharged stroke patient for early recovery. This shows that there might be a lack of realization that family care and support can be helpful to stroke patients to have a happy and healthy life.

Although 88.9% students, when they witness a stroke patient, will prefer to take the person to a hospital, 64.1% chose only to take to the hospital rather than sprinkling water on their face or waiting for spontaneous recovery. In a survey done by Reeves et al., in response to a situation while encountering stroke, 79% of the respondents preferred calling emergency and 90% of the respondents suggested immediate medical treatment.[24]

Students with good knowledge about risk factors and warning signs tended to choose to take a stroke patient to a hospital. There was a significant association between response choosing to take to a hospital if they witness a person with stroke and risk factor identified as well as warning symptoms identified. The binary logistic regression analysis also showed that identification of at least one risk factor and identification of at least one warning symptoms are good predictors of response choosing to take a patient to a hospital. Identification of ≥1 risk factor increases the odds of choosing to take a patient witnessed with stroke to a hospital by 3.92 times as compared to those with no risk factor identified. Similarly, identification of ≥1 warning signs increases the odds of choosing to take a patient witnessed with stroke to a hospital by 2.83 times as compared to those with no warning sign identified. This suggests that improving the knowledge about risk factors and warning signs of stroke improves the awareness to seek hospital emergency.

Our report has all the inherent limitations of research based on a self-structured questionnaire used for research. Furthermore, all the schools surveyed were located in urban and semi-urban areas and were private schools; students in rural schools and government school students were not included in the study. In addition to this, as Nepal is a country with diverse sociocultural and linguistic practices, our findings cannot be extrapolated to other parts of the country. The scenario of knowledge status could be worse in the disadvantaged and poor areas of Nepal. Finally, the quantitative nature of the study using structured questions with “yes” or “no” answers does not permit exploration of the reasons why the respondents hold particular views about stroke. Although our report has limitations, it clearly demonstrates the lack of knowledge, misconception, and identified students who are likely to take a patient to the hospital at the earliest. This can help better outcome of the case with recently introduced thrombolytic therapy in Nepal.[25]

Conclusion

We demonstrated a school survey to clarify baseline KAP about stroke among high school students in Nepal. KAP seemed well but still a few misconceptions were present. There is a need of widespread stroke educational program at schools level to promote KAP toward stroke and save people with stroke in developing countries like Nepal.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank nursing staffs of the Department of Neurology of CMS-TH, Nepal. Our sincere thank to Ms. Dipa Chapagain and Ms. Kalpana Pokharel for helping us throughout the study.

References

- 1.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: Systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367:1747–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandit A, Arjyal A, Farrar J, Basnyat B. Neuological letter from Nepal. Pract Neurol. 2006;6:129–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaik MM, Loo KW, Gan SH. Burden of stroke in Nepal. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:517–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Heart, stroke and vascular diseases-Australian facts 2004. Cardiovascular disease series 22. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 03]. Available from: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=6442454948 .

- 5.United Nations Development Programme. Nepal Human Development Report 2009 – State Transformation and Human Development. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Bonita R, Belanger AJ. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for stroke. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1988;259:1025–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferro JM, Melo TP, Oliveira V, Crespo M, Canhão P, Pinto AN. An analysis of the admission delay of acute strokes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 1994;4:72–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Zoppo GJ, Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Pessin MS, Rowley HA, Gent M. PROACT: A phase II randomized trial of recombinant pro-urokinase by direct arterial delivery in acute middle cerebral artery stroke. PROACT Investigators. Prolyse in acute cerebral thromboembolism. Stroke. 1998;29:4–11. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnan GA, Davis SM, Chambers BR, Gates PC, Hankey GJ, McNeil JJ, et al. Streptokinase for acute ischemic stroke with relationship to time of administration: Australian Streptokinase (ASK) Trial Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276:961–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Toni D, Lesaffre E, von Kummer R, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European cooperative acute stroke study (ECASS) JAMA. 1995;274:1017–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuzono K, Yokota C, Takekawa H, Okamura T, Miyamatsu N, Nakayama H, et al. Effects of stroke education of junior high school students on stroke knowledge of their parents: Tochigi project. Stroke. 2015;46:572–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ennen K, Zerwic J. Stroke knowledge: How is it impacted by rural location, age, and gender? Óline J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2010;10:9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Góngora-Rivera F, Gutiérrez-Jiménez E, Zenteno MA. GEPEVC Investigators. Knowledge of ischemic stroke among a Mexico City population. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;18:208–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stroebele N, Müller-Riemenschneider F, Nolte CH, Müller-Nordhorn J, Bockelbrink A, Willich SN. Knowledge of risk factors, and warning signs of stroke: A systematic review from a gender perspective. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:60–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx JJ, Klawitter B, Faldum A, Eicke BM, Haertle B, Dieterich M, et al. Gender-specific differences in stroke knowledge, stroke risk perception and the effects of an educational multimedia campaign. J Neurol. 2010;257:367–74. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aycock DM, Kirkendoll KD, Coleman KC, Albright KC, Alexandrov AW. Abstract NS6: Family History of Stroke: Invisibility of a Key Stroke Risk Factor among High Risk African Americans. Stroke. 2013;44(Suppl 1):ANS6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin A, Heng BH, Toh MPHS, Wong LY, Venketasubramanian N, Cheah JTS. Impact of family history on the knowledge, attitude, belief and practice of stroke and its risk factors among Singaporeans. Combined Scientific Meeting 05, National healthcare group; Singapore, 4-6 November. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sug Yoon S, Heller RF, Levi C, Wiggers J, Fitzgerald PE. Knowledge of stroke risk factors, warning symptoms, and treatment among an Australian urban population. Stroke. 2001;32:1926–30. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.8.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandian JD, Kalra G, Jaison A, Deepak SS, Shamsher S, Singh Y, et al. Knowledge of stroke among stroke patients and their relatives in Northwest India. Neurol India. 2006;54:152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YS, Park SS, Bae HJ, Heo JH, Kwon SU, Lee BC, et al. Public awareness of stroke in Korea: A population-based national survey. Stroke. 2012;43:1146–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.638460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankar PR, Paudel R, Giri BR. Healing traditions in Nepal. JAAIM-Online [Internet] [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 03]. Available from: http://www.aaimedicine.com/jaaim/sep06/Healing.pdf .

- 23.Bernhardt J, Cramer SC. Giant steps for the science of stroke rehabilitation. Int J Stroke. 2013;8:1–2. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeves MJ, Hogan JG, Rafferty AP. Knowledge of stroke risk factors and warning signs among Michigan adults. Neurology. 2002;59:1547–52. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000031796.52748.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thapa L, Shrestha S, Shrestha P, Bhattarai S, Gongal DN, Devkota UP. Feasibility and efficacy of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: A study from National Institute of Neurological and Allied Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2016;7:55–60. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.172161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]