Abstract

Background

The Early Cancer Detection Consortium is developing a blood-test to screen the general population for early identification of cancer, and has therefore conducted a systematic mapping review to identify blood-based biomarkers that could be used for early identification of cancer.

Methods

A mapping review with a systematic approach was performed to identify biomarkers and establish their state of development. Comprehensive searches of electronic databases Medline, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane library and Biosis were conducted in May 2014 to obtain relevant literature on blood-based biomarkers for cancer detection in humans. Screening of retrieved titles and abstracts was performed using an iterative sifting process known as “data mining”. All blood based biomarkers, their relevant properties and characteristics, and their corresponding references were entered into an inclusive database for further scrutiny by the Consortium, and subsequent selection of biomarkers for rapid review. This systematic review is registered with PROSPERO (no. CRD42014010827).

Findings

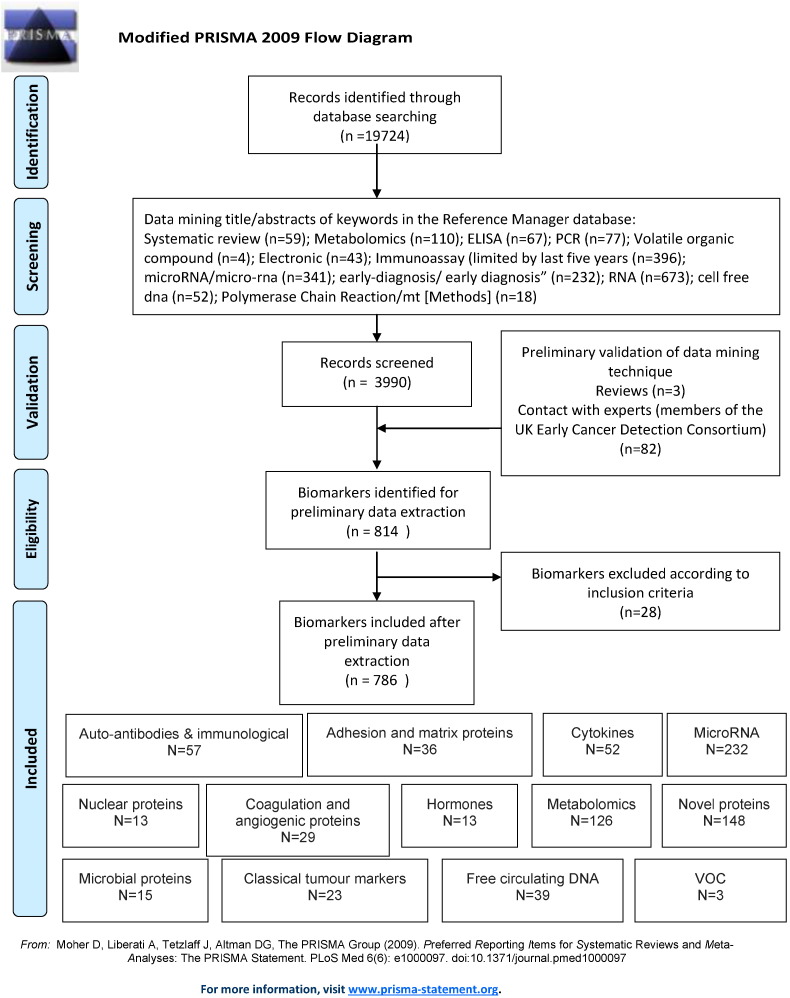

The searches retrieved 19,724 records after duplicate removal. The data mining approach retrieved 3990 records (i.e. 20% of the original 19,724), which were considered for inclusion. A list of 814 potential blood-based biomarkers was generated from included studies. Clinical experts scrutinised the list to identify miss-classified and duplicate markers, also volunteering the names of biomarkers that may have been missed: no new markers were identified as a result. This resulted in a final list of 788 biomarkers.

Interpretation

This study is the first to systematically and comprehensively map blood biomarkers for early detection of cancer. Use of this rapid systematic mapping approach found a broad range of relevant biomarkers allowing an evidence-based approach to identification of promising biomarkers for development of a blood-based cancer screening test in the general population.

Keywords: Cancer, Early detection, Biomarker, Assay, Diagnosis, Blood, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

There are a large number of biomarkers with potential utility for early cancer detection from blood samples

-

•

Few biomarkers have been studied sufficiently with clinical validation to allow their use in combination for screening in the general population

-

•

We used an iterative mapping review of 20,000 references, retrieving 3,990 relevant papers, and identified 788 markers in blood of potential use

Screening for cancer can save lives, but it is difficult to justify individual screening programmes for many cancer types. However, cancers of different types share many attributes, and markers of cancer biology found in the blood. We surveyed the literature to identify known biomarkers using a new mapping approach. With nearly 20,000 papers on the subject, we retrieved 3990 papers, and identified 788 markers in blood of potential use. Most have not been studied enough to justify their use in clinical practice. This evidence based approach should help us to develop a blood-based cancer screening test in the general population.

1. Introduction

Early detection of cancer results in improved survival (Etzioni et al., 2003, Wolf et al., 2010, McPhail et al., 2015). Cancers detected early require less extensive treatment and are less likely to have spread to other organs. Cancer diagnosis requires histological examination of tissue abnormalities detected by radiological, clinical or endoscopic examination of patients. Detection, as opposed to diagnosis, relies on screening a largely asymptomatic population to identify people who may be at higher risk of having cancer than others. Screening tests for cancer, or any other condition need to fulfil strict criteria to prevent the implementation of inappropriate screening, ensuring screening is cost effective and benefits patients. The criteria applied within the UK are listed at http://www.screening.nhs.uk/criteria, based on those developed by Wilson and Jungner (Cochrane and Holland, 1971, Wilson and Jungner, 1968). For early cancer detection, a blood-based screening test would have to be cost effective and demonstrate a meaningful clinical benefit which outweighs the harms associated with false positive, indeterminate results and overtreatment. This is clearly a major undertaking, and needs a multidisciplinary approach.

The Early Cancer Detection Consortium (ECDC) was established in 2012 in the United Kingdom and comprises 23 universities, their associated NHS hospitals, as well as other organisations and industry partners. The consortium was established to investigate whether a cost-effective screening test can be used in the general population to identify people with early cancers. Given the extensive literature on blood biomarkers for cancer, it is logical to explore the development of such a test using existing biomarkers that have the best evidence-base for cancer detection. A sensitive blood test for multiple tumour types could enable people with biomarker levels which are outside the typical range to receive further investigation and lead to earlier diagnosis of cancer at an asymptomatic stage when curative treatment is feasible. The next stage of the programme will involve analytical and clinical validation of these biomarkers in a case control study, from which a detection algorithm will be produced and validated for possible use as a generic cancer screen. Finally, a randomised controlled trial will be required to determine the clinical and cost-effectiveness of the resulting screening strategy.

Previous reviews in this area have understandably been limited in scope, usually restricted to one biomarker or well-defined group of potential markers, due to the enormous number of publications in the field. The aim of this study was therefore to establish the full range of candidate blood-based biomarkers with potential for the early detection of cancer, and map key characteristics of the tests.

2. Methods

To identify all relevant biomarkers, comprehensive searches and innovative methods to perform the mapping review were employed to cope with the sizeable body of relevant literature to be assessed within a short time-frame. The mapping review comprised the following stages: comprehensive literature searches; data mining techniques for rapid screening of the search records and; development of a customizable database of evidence to optimise the output from the mapping review. It was not considered sufficient simply to list evidence by reference or to name the biomarker once in a spreadsheet and continue searching until another new biomarker was found. Instead it was more useful and time-efficient to maintain the corresponding citations for each biomarker and record the basic characteristics of the study at the time of screening. This enabled a basic informative profile to be built for each biomarker identified in the mapping review.

This systematic review is registered with PROSPERO (no. CRD42014010827) and the methods have been structured around the PRISMA checklist (http://www.prisma-statement.org/).

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies included all English language studies from the past five years that investigated blood based biomarkers in more than 50 patients, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the systematic mapping review.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| English language studies | Studies published in non-English language |

| Studies within the last five years (2010–2014) | Studies from 2009 or older |

| Controlled studies | No healthy control group |

| Validation studies | Derivative studies from included papers |

| Cancer detection/diagnosis | Prognosis or prediction (treatment response) associated markers |

| 50 or more patients | Less than 50 patients |

| Biomarkers measured in blood | Tissue or other bodily fluid samples |

| Abstracts of panels which do not state which biomarkers are studied | |

| Citation titles without abstracts |

2.2. Search Strategy

To identify a comprehensive body of literature from which a list of candidate biomarkers could be generated, a broad search using keywords and subject headings was undertaken. The terms reflected the concepts of ‘diagnosis’, ‘markers’, ‘blood’ and ‘screening’ (see supplementary material). The keywords and subject headings were developed using a variety of collaborative methods between Information Specialists and Systematic Reviewers at the University of Sheffield and researchers at the University of Warwick.

A scoping search was performed and assessed for appropriateness. Additionally, key journal articles and abstracts in Medline were retrieved and assessed to obtain relevant subject headings and keywords. Clinical input was sought from members of the ECDC to verify and validate the chosen keywords. For the full search, relevant free-text, keyword and thesaurus terms were combined using Boolean operators and translated into database specific syntax. Full searches were limited to English language, humans and publication dated from 2010 to May 2014. The databases searched were Medline and Medline in Process, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane Library (including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE, CENTRAL, HTA, NHS EED), Science Citation Index Expanded, Conference Proceedings Citation Index - Science, Book Citation Index – Science, and Biosis Previews.

The initial search strategy was broad and inclusive. As a result, a large number of relevant records were obtained. Preliminary validation by consulting experts in the field indicated that the search was sensitive and no missing relevant literature was identified.

2.3. Sifting and Data Mining

The results of the initial searches were imported into a Reference Manager database. To identify an exhaustive list of biomarkers, retrieved records were searched iteratively within the Reference Manager database, using keywords to select potentially relevant titles. Titles and abstracts of this selection of citations were scrutinised for names and descriptions of biomarkers that met (or potentially met) the selection criteria (see Table 1). The citations were tagged to indicate that they had been viewed, to enable their exclusion from further searches. Relevant citations were exported to a Microsoft Access database which was customised to allow data extraction of relevant key information for each biomarker that was available from the corresponding study abstracts.

The data mining process within the main database included the following restrictions (see Box 1):

Box 1. Data mining process restrictions.

| Restriction | Justification |

|---|---|

|

To ensure that the biomarkers identified and their associated evidence is current and relevant, searches were restricted to records published in the last five years (from 2010 to May 2014). |

|

Data mining involved interrogation of search results using relevant keywords (Box 2) to search within the database of total records for batches of references. Keywords were identified through consultation with ECDC members for known technologies, and for other potentially relevant terms. Keywords for similar concepts (e.g. synonyms for a specific biomarker) were grouped and searched together. Keywords expected to retrieve citations of high relevance were prioritised over those with less obvious relevance. Further keywords were identified by the review team by consideration of indexing keywords and content of studies identified as relevant. |

|

One reviewer screened the references to generate the list of biomarkers using the data mining technique. A single reviewer screening approach was mitigated for by the examination review papers and consultation with ECDC membership during a later validation phase. An inclusive approach to inclusion was adopted to minimise inappropriate exclusions. |

|

Titles without abstracts were not included. Equally abstracts of primary studies or reviews which did not name a biomarker were not included. Titles and abstracts retrieved from each batch of references associated with each keyword were assessed against the eligibility criteria in Table 1. |

Alt-text: Box 1

To ensure a comprehensive capture of all relevant biomarkers, a further validation stage was performed. Relevant reviews identified during the search were used to check for additional biomarkers not generated by the data mining process. ECDC members were invited to recommend papers that they believed to be relevant to the mapping review.

2.4. Data Collection

Each biomarker occupied a record with a unique identifier number in a customised Microsoft Access database which stored the number of associated papers, the abstract and reference details; associated synonyms and acronyms; types of cancers and study design; keywords used to retrieve the abstract during data mining; assays used to measure the biomarker, where reported; category to which the biomarker was assigned (e.g. auto-antibodies); and the sample types used, where reported (e.g. serum, plasma or whole blood).

2.5. Results

After duplicates were removed, 19,724 records were yielded from the comprehensive searches. Using data mining, 3990 titles and abstracts were retrieved from the 19,724 records for full scrutiny. Data mining is the process of pulling a subset of records from a large, unwieldy dataset. The subset of 3990 abstracts was reviewed in order to generate a list of biomarkers which are potentially relevant to early identification of cancer using blood. A full breakdown of the keywords used and the number of corresponding records retrieved can be seen in Fig. 1. During the validation process, three relevant reviews were consulted for the identification of any additional biomarkers. No further biomarkers were identified either from these reviews or from the consultation of ECDC members.

Fig. 1.

Modified PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

A total of 814 biomarkers were identified as potentially relevant to the review question and were subjected to further scrutiny, identifying duplicates and miss-classified biomarkers during a process of data cleaning and categorising the biomarkers into groups or families. These groups are currently arranged by molecular function in order to map the biomarkers by biological origin. Further research using this methodology and database into the empirical application and validation of each biomarker will allow the biomarkers to be grouped by clinical utility such as cancer type or platform. However, we have performed this analysis for colorectal cancer (Table 2) and lung cancer (Table 3) to illustrate how these data could be used to define cancer-specific biomarkers. This resulted in a final total of 788 biomarkers, grouped into 13 initial categories (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Table 4, Supplementary Table 5, Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Table 8, Supplementary Table 9, Supplementary Table 10, Supplementary Table 11, Supplementary Table 12, Supplementary Table 13) as follows:

-

1.

Adhesion and matrix proteins (n = 36). The expression of molecules involved in adhesion or in formation of the connective tissue matrix around cancer cells differ from non-neoplastic cells and appear in blood. Early work included collagen breakdown products, which are produced as a result of increased collagen turnover, but are not specific to particular tumour types (Paterson et al., 1991, Berruti et al., 1995). Collagens are metabolised by matrix metalloproteinase proteins (MMPs), these in turn are antagonised by tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (Roy et al., 2009). Both MMPs and TIMPs are represented in this group. Turnover of other matrix proteins is altered in cancer: vimentin (Ludwig et al., 2009), laminin (Schechter & Lopes, 1990) and tenascin are included in the list. Cancer cells have increased motility compared with non-neoplastic cells, and show altered expression of adhesion molecules. EpCAM, e-cadherin, and e-selectin are represented as blood biomarkers in the list (Beije et al., 2015, Hauselmann and Borsig, 2014, Gires and Stoecklein, 2014). Following review, a total of 18 were removed, including one duplicate entry.

-

2.

Auto-antibodies and immunological markers (n = 59). The majority of entries in this category relate to auto-antibodies. These have been described for a wide variety of proteins within cancer, notably nuclear proteins such as P53 and other nuclear proteins, and occur in many cancers (Middleton et al., 2014). Immunological markers of interest include CRP, usually regarded as a marker of inflammation.

-

3.

Classical Tumour Markers. A total of 23 markers were included in the ‘classical’ tumour marker group. This includes those used widely in practice, including CEA, CA125, CA15-3, CA19-9, AFP, and PSA. Markers of lesser utility, such as LDH and HE4 were also included. It should be noted that several of these (CA15-3 and CA19-9) refer to different epitopes of the same antigen, MUC1, which also came up in our searches.

-

4.

Coagulation & angiogenic proteins. Of the 29 proteins in this category, the majority had relatively little evidence for their utility in early cancer detection. The markers can be sub-categorised into those connected to angiogenesis (e.g. VEGF, PlGF, Angiopoietins) and coagulation (e.g. plasminogen activating proteins and kallikreins). Annexins were included in this group, though they are more often thought of as apoptosis associated proteins.

-

5.

Cytokines, chemokines and insulin-like growth factors. 52 biomarkers were included in this group. They include a wide range of cytokines and soluble receptors. Evidence for these is limited, but they represent an interesting group of proteins abnormal in cancer, measurement of which is likely to reflect the profound local immune suppression and systemic alteration of immunity present in cancers.

-

6.

Circulating-free DNA. This is usually abbreviated as cfDNA, though increasingly the term circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) is used. While DNA is clearly a single biomarker, 39 individual biomarkers representing genes or alterations of most interest were identified in this group, though in essence any mutation of gene methylation marker identified would be part of this group. While the first descriptions of cfDNA used PCR (Lo, 2001a, Lo, 2001b), many recent papers apply multi-analyte methods, including next generation sequencing (Coco et al., 2015, Rothe et al., 2014, Couraud et al., 2014), to the study of cfDNA to detect mutations of potential diagnostic significance. Though as yet few have used this for early detection.

-

7.

Hormones. While 13 biomarkers were assigned to this category, only Corticosteroid-binding globulin survives more stringent searches (Wu et al., 2012). Hormone levels are not thought to be reliable markers of cancer.

-

8.

Metabolomics. A large number of metabolites are known to be altered in cancer, as the result of changes in energy, lipid, amino acid, and protein metabolism. We identified 126 individual markers, many of which were measured in concert by mass spectroscopy within several studies (Cross et al., 2014, Hasim et al., 2013).

-

9.

MicroRNA and other RNAs. There are now over 1000 human miRNA species known, a large number of these have been studied in cancer. While the majority have been looked at in tissue, there is considerable interest in their possible use as a liquid biopsy, our list of 232 biomarkers in this group reflects this. They are rarely measured alone: most use some form of array strategies for measurement, most studies concentrate on single cancer types (Fortunato et al., 2014, Clancy et al., 2014).

-

10.

Novel Proteins. A large number of protein biomarkers, often identified by mass spectroscopy or 2D gel electrophoresis, were hard to categorise. These were grouped as novel proteins and represent a diverse group of 148 biomarkers. Examples include alpha-2-heremans-schmid-glycoprotein (AHSG) (Dowling et al., 2012) and galectin (Gromov et al., 2010) in breast cancer.

-

11.

Nuclear proteins. A group of 13 nuclear protein biomarkers were assigned to this category, though some markers within the novel protein group are of nuclear origin. Circulating nucleosomes are included in this group as they are usually detected by ELISA (Holdenrieder et al., 2014).

-

12.

Microbial proteins (n = 15). A small number of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) proteins and their antibodies have been studied as early cancer biomarkers in blood, based on the detection of EBV DNA in cancer patients (Lo, 2001b). Helicobacter antibodies also fall into this group.

-

13.

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC). Only three biomarkers, all small metabolites, were assigned to this category, which it could be argued forms part of the metabolite group. It is however measured differently.

Table 2.

Colorectal cancer specific biomarkers from all 13 categories.

| Biomarker categories | ID no | Biomarker | Acronym | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion and matrix proteins | 7 | Clusterin | CLI | Colorectal |

| 12 | Ep cell adhesion module (GA733-2) | EpCAM (GA733-2) | Colorectal | |

| 22 | Metallopeptidase inhibitor 1 | TIMP1; TIMP-1 | Colorectal | |

| Auto-antibodies & immunological markers | 2 | Anti-p53 antibodies | p53; serum p53 antibodies; p53-Abs; p-53-AAB; Anti-p53Ab | Colorectal |

| 19 | Anti-heat shock protein 60 | HSP60 | Colorectal | |

| 40 | IL2RB | IL2RB | Colorectal | |

| Classical tumour markers | 3 | Carcinoembryonic antigen | CEA | Colorectal |

| 8 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 | CA19-9; CA199 | Colorectal | |

| Coagulation and angiogenesis molecules | 2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor | VEGF | Colorectal |

| 8 | Kininogen-1 | Kininogen-1 | Colorectal | |

| 23 | Endothelial cell-specific molecule-1 | ESM-1 | Colorectal | |

| 27 | Thrombomodulin | THBD-M | Colorectal | |

| 28 | Annexin A3 | ANXA3 | Colorectal | |

| Cytokines, chemokines and insulin-like growth factors | 3 | Interleukin 8 | IL-8 | Colorectal |

| 17 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-2 | IGFBP-2 | Colorectal | |

| 26 | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor | BDNF | Colorectal | |

| 28 | Interleukin-1ra | IL-1ra | Colorectal | |

| 50 | TNFAIP6 | TNFAIP6 | Colorectal | |

| Circulating-free DNA | 3 | Adenomatous polyposis coli | APC | Colorectal |

| 9 | Septin 9 | Septin 9 | Colorectal | |

| 17 | Methylation of CYCD2 | CYCD2 | Colorectal | |

| 18 | Methylation of HIC1 | HIC1 | Colorectal | |

| 19 | Methylation of PAX 1 | PAX 1 | Colorectal | |

| 20 | Methylation of RB1 | RB1 | Colorectal | |

| 21 | Methylation of SRBC | SRBC | Colorectal | |

| 34 | Line1 79 bp | Line1 79 bp | Colorectal | |

| 35 | Line1 300 bp | Line1 300 bp | Colorectal | |

| 36 | Alu 115 bp | Alu 115 bp | Colorectal | |

| 37 | Alu 247 bp | Alu 247 bp | Colorectal | |

| Hormones | Nil | Nil | ||

| Metabolic markers | 1 | Plasma glucose levels | Plasma glucose levels | Colorectal |

| 5 | 3-Hydroxypropionic acid and pyruvic acid | 3-Hydroxypropionic acid and pyruvic acid | Colorectal | |

| 6 | Alanine | l-Alanine, glucuronoic lactone | Colorectal | |

| 7 | l-Glutamine | Glutamine | Colorectal | |

| 8 | Sarcosine | Sarcosine | Colorectal | |

| 11 | Choline | Phosphatidylcholine; (PC) (34 : 1) | Colorectal | |

| 12 | Phosphatidylinositol | Phosphatidylinositol | Colorectal | |

| 17 | l-Valine | Valine | Colorectal | |

| 18 | l-Threonine | Threonine | Colorectal | |

| 19 | 1-Deoxyglucose | 1-Deoxyglucose | Colorectal | |

| 20 | Glycine | Glycine | Colorectal | |

| 21 | MACF1 | MACF1 | Colorectal | |

| 22 | Apolipoprotein H | APOH; beta-2-glycoprotein | Colorectal | |

| 23 | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | A2M | Colorectal | |

| 24 | Immunoglobulin lambda locus | IGL@ | Colorectal | |

| 25 | Vitamin D-binding protein | VDB | Colorectal | |

| 30 | 2-Hydroxyglutarate | 2-Hydroxyglutarate | Colorectal | |

| 34 | 2-Hydroxybutyrate | 2-Hydroxybutyrate | Colorectal | |

| 35 | Aspartic acid | Aspartic acid | Colorectal | |

| 36 | Kynurenine | Kynurenine | Colorectal | |

| 37 | Cystamine | Cystamine | Colorectal | |

| 50 | Tricarboxylic acid | TCA | Colorectal | |

| 53 | 2-Aminoethanesulfonic acid | Taurine | Colorectal | |

| 54 | Lactate | Lactate | Colorectal | |

| 55 | Phosphocholine | Phosphocholine | Colorectal | |

| 56 | Proline | Proline | Colorectal | |

| 57 | Phenylalanine | Phenylalanine | Colorectal | |

| 102 | Oleamide | Oleamide | Colorectal | |

| 111 | Leukocyte methylated cytosine 5 | 5-mC | Colorectal | |

| 116 | Plasma choline-containing phospholipids | Plasma phospholipids | Colorectal | |

| 120 | Palmitic amide | Palmitic amide | Colorectal | |

| 121 | Hexadecanedioic acid | Hexadecanedioic acid | Colorectal | |

| 122 | Octadecanoic acid | Octadecanoic acid | Colorectal | |

| 123 | Eicosatrienoic acid | Eicosatrienoic acid | Colorectal | |

| 124 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 18:2 | LPC(18:2) | Colorectal | |

| 125 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 16:0 | LPC(16:0) | Colorectal | |

| MicroRNA and other RNAs | 5 | let-7g | Colorectal | |

| 15 | miR-126 | miR-126 | Colorectal | |

| 32 | miR-135b | miR-135b | Colorectal | |

| 36 | miR-141 | miR-141 | Colorectal | |

| 38 | miR-143 | miR-143 | Colorectal | |

| 39 | miR-145 | miR-145 | Colorectal | |

| 57 | miR-17-3p | miR-17-3p | Colorectal | |

| 68 | miR-18a | miR-18a | Colorectal | |

| 71 | miR-191-5p | miR-191-5p | Colorectal | |

| 94 | miR-20a | miR-20a | Colorectal | |

| 95 | miR-21 | miR-21 | Colorectal | |

| 125 | miR-29a | miR-29a | Colorectal | |

| 187 | miR-548as-3p | miR-548as-3p | Colorectal | |

| 195 | miR-601 | miR-601 | Colorectal | |

| 210 | mir-760 | mir-760 | Colorectal | |

| 214 | miR-885-5p | miR-885-5p | Colorectal | |

| 219 | miR-92a | miR-92a | Colorectal | |

| 231 | U6 snRNA (U6) | U6 snRNA (U6) | Colorectal | |

| Novel proteins | 15 | Microtubule-associated protein RP/EB family member 1 | MAPRE1 | Colorectal |

| 16 | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | LRG1 | Colorectal | |

| 56 | Alpha-enolase | Alpha-enolase | Colorectal | |

| 62 | Betaine | Betaine | Colorectal | |

| 72 | CACNAG1 | CACNAG1 | Colorectal | |

| 82 | Colon cancer specific antigen-2 | CCSA-2 | Colorectal | |

| 88 | C9orf50-M | C9orf50-M | Colorectal | |

| 89 | CLEC4D | CLEC4D | Colorectal | |

| 90 | LMNB1 | LMNB1 | Colorectal | |

| 91 | PRRG4 | PRRG4 | Colorectal | |

| 92 | VNN1 | VNN1 | Colorectal | |

| 103 | Dermokine-beta | DK-beta | Colorectal | |

| 105 | Seprase | Seprase | Colorectal | |

| 126 | Serum amyloid A | SAA | Colorectal | |

| 132 | Lipocalin 2 | Lipocalin 2 | Colorectal | |

| Nuclear proteins | 2 | k-ras | k-ras | Colorectal |

| Microbial proteins | Nil | Nil | ||

| Volatile organic compounds | 1 | Phenyl methylcarbamate | Phenyl methylcarbamate | Colorectal |

| 2 | Ethylhexanol | Ethylhexanol | Colorectal | |

| 3 | 6-t-Butyl-2,2,9,9-tetramethyl-3,5- decadien-7-yne | 6-t-Butyl-2,2,9,9-tetramethyl-3,5-decadien-7-yne | Colorectal |

Table 3.

Example for lung cancer and mesothelioma specific biomarkers from all 13 categories.

| Biomarker categories | ID no | Biomarker | Acronym | Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion and matrix proteins | 2 | Calreticulin | CRT | Lung |

| 7 | Clusterin | CLI | Lung | |

| 8 | Cross-linked telopeptide of type I collage | ICTP | Lung | |

| 9 | E-cadherin | E-cadherin; soluble E-cadherin (sE-cad) | Lung | |

| 10 | E-cadherin gene CDH1 | CDH1 | Lung | |

| 11 | E-selectin | E-selectin; sE-selectin | Lung | |

| 19 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 | MMP2 | Lung | |

| 29 | Soluble L-selectin | sL-selectin | Lung | |

| 31 | Surfactant protein-D | SP-D | Lung | |

| Auto-antibodies & immunological markers | 2 | Anti-p53 antibodies | p53; serum p53 antibodies; p53-Abs; p-53-AAB; Anti-p53Ab | Lung |

| 3 | Anti-survivin antibodies | Survivin/anti-survivin antibodies | Lung | |

| 6 | Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase | IMPDH | Lung | |

| 8 | Immunoglobulin G | IgG | Lung | |

| 12 | Anti-livin | Livin/anti-livin antibodies | Lung | |

| 22 | C-reactive protein | CRP | Lung | |

| 28 | Anti-Krebs von Lungren-6 | KL-6 | Lung | |

| 30 | Anti-ubiquillin | Ubiquillin | Lung | |

| 32 | Alpha-crystallin IgG antibodies | Alpha-crystallin antibodies | Lung | |

| 37 | CD30 | CD30 | Lung | |

| 38 | CD63 | CD63 | Lung | |

| 43 | NY-ESO-1 | NY-ESO-1 | Lung | |

| 44 | CAGE | CAGE | Lung | |

| 45 | GBU4-5 | GBU4-5 | Lung | |

| 46 | SOX2 | SOX2 | Lung | |

| 47 | HuD | HuD | Lung | |

| 48 | IgM autoantibodies | IgM autoantibodies | Lung | |

| 55 | Anti-hydroxysteroid-(17-alpha)-dehydrogenase | Lung | ||

| 56 | Anti-triosephosphate isomerase | Lung | ||

| Classical tumour markers | 2 | Cancer antigen 15-3 | CA15-3; CA 15-3 | Lung |

| 3 | Carcinoembryonic antigen | CEA | Lung | |

| 6 | Human epididymis protein 4 | HE4 | Lung | |

| 9 | Squamous cell carcinoma antigen | SCCA; SCC-ag | Lung | |

| 11 | Cytokeratin fragment 19 | CYFRA 21-1 | Lung | |

| 12 | Neuron Specific Enolase | NSE | Lung | |

| 14 | Progastrin-releasing peptide | proGRP | Lung | |

| 22 | HER2 | HER2; AB_HER2; 36 HER2 negative; erbb-2; soluble human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (sHER2) | Lung | |

| Coagulation and angiogenesis molecules | 1 | Urokinase plasminogen activator | uPA/uPAR/suPAR | Lung |

| 2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor | VEGF | Lung | |

| 10 | Endothelin-1 | ET-1 | Lung | |

| 13 | Angiopoietin-2 | Angiopoietin-2; Apo-2 | Lung | |

| 14 | Thrombospondin-1 | THBS1 | Lung | |

| 15 | Plasminogen activator inhibitor | Plasminogen activator inhibitor | Lung | |

| 19 | Endostatin | Endostatin | Lung | |

| 21 | Annexin A1 | ANXA1 mNRA | Lung | |

| 24 | C4d | C4d | Lung | |

| 25 | Annexin A2 | ANXA2 | Lung | |

| Cytokines, chemokines and insulin-like growth factors | 7 | Tumour necrosis factor [alpha] | TNF[alpha]; DcR3 | Lung |

| 10 | Macrophage migration inhibitory factor | MIF | Lung | |

| 18 | Hepatocyte growth factor | HGF | Lung | |

| 19 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein | IGFBP-3 | Lung | |

| 20 | Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor | G-CSF | Lung | |

| 21 | Interleukin 3 | IL-3 | Lung | |

| 22 | Stem cell factor | SCF | Lung | |

| 25 | C-C motif chemokine 5 | C-C motif chemokine 5 | Lung | |

| 28 | Interleukin-1ra | IL-1ra | Lung | |

| 29 | Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 | MCP-1 | Lung | |

| 31 | Midkine | MK; MDK | Lung | |

| 38 | IRF1 | IRF1 | Lung | |

| 51 | Macrophage inflammatory protein 4 | MIP-4 | Lung | |

| 52 | Megakaryocyte potentiating factor | MPF | Mesothelioma | |

| Circulating-free DNA | 1 | Microsatellite alterations at FHIT | FHIT | Lung |

| 2 | Microsatellite alterations at loci on chromosome 3 | 3p loci | Lung | |

| 3 | Adenomatous polyposis coli | APC | Lung | |

| 4 | CHD1 | CHD1 | Lung | |

| 5 | O(6)-Methyl-guanine-DNA methyltransferase | MGMT | Lung | |

| 6 | DCC | DCC | Lung | |

| 7 | RASSF1A | RASSF1A | Lung | |

| 8 | absent in melanoma 1 | AIM1; beta/gamma crystallin domain-containing protein 1 | Lung | |

| Hormones | 9 | Progesterone receptor B | PRB | Lung |

| 13 | Prolactin | Prolactin | Lung | |

| Metabolic markers | 6 | Alanine | l-Alanine, glucuronoic lactone | Lung |

| 26 | Leucine | Leucine; isoleucine | Lung | |

| 27 | Histidine | Histidine | Lung | |

| 28 | Tryptophan | Tryptophan | Lung | |

| 29 | Ornithine | Ornithine | Lung | |

| 38 | Lactic acid | Lactic acid | Lung | |

| 39 | Glycelic acid | Glycelic acid | Lung | |

| 40 | Glycolic acid | Glycolic acid | Lung | |

| 87 | NG1A2F | NG1A2F | Lung | |

| 89 | N-glycopeptides | Glycopeptides | Mesothelioma | |

| 102 | Oleamide | Oleamide | Lung | |

| 103 | Long chain acyl carnitines | Long chain acyl carnitines | Lung | |

| 104 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 18:1 | LPC(18:1) | Lung | |

| 105 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 20:4 | LPC(20:4) | Lung | |

| 106 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 20:3 | LPC(20:3) | Lung | |

| 107 | Lysophosphatidylcholine 22:6 | LPC(22:6) | Lung | |

| 108 | Serum metabolite 16:0/1 | SM(16:0/1) | Lung | |

| 115 | Ferritin | FTL | Lung | |

| MicroRNA and other RNAs | 7 | miR-103 | miR-103 | Mesothelioma |

| 14 | miR-1254 | miR-1254 | Lung | |

| 15 | miR-126 | miR-126 | Mesothelioma | |

| 20 | miR-128b | miR-128b | Lung | |

| 29 | miR-133a | miR-133a | Lung | |

| 35 | miR-140 | miR-140 | Lung | |

| 38 | miR-143 | miR-143 | Lung | |

| 41 | miR-1468 | miR-1468 | Lung | |

| 43 | miR-146b-3p | miR-146b-3p | Lung | |

| 50 | miR-155 | miR-155 | Lung | |

| 53 | miR-15b | miR-15b | Lung | |

| 60 | miR-181c | miR-181c | Lung | |

| 61 | miR-182 | miR-182 | Lung | |

| 68 | miR-18a | miR-18a | Lung | |

| 80 | miR-197 | miR-197 | Lung | |

| 95 | miR-21 | miR-21 | Lung | |

| 98 | miR-212 | miR212 | Lung | |

| 106 | miR-220 | miR-220 | Lung | |

| 108 | miR-221 | miR-221 | Lung | |

| 111 | miR-23a | miR-23a | Lung | |

| 122 | miR-27b | miR-27b | Lung | |

| 135 | miR-30c-1* | miR-30c-1* | Lung | |

| 145 | miR-330 | miR-330 | Lung | |

| 147 | miR-331 | miR-331 | Lung | |

| 152 | miR-339-5p | miR-339-5p | Lung | |

| 157 | miR-345 | miR-345 | Lung | |

| 158 | miR-346 | miR-346 | Lung | |

| 172 | miR-377 | miR-377 | Lung | |

| 180 | miR-484 | miR-484 | Lung | |

| 188 | miR-548b | miR-548b | Lung | |

| 189 | miR-550 | miR-550 | Lung | |

| 190 | miR-566 | miR-566 | Lung | |

| 192 | miR-574–5p | miR-574–5p | Lung | |

| 197 | miR-616* | miR-616* | Lung | |

| 198 | miR-625* | miR-625* | Mesothelioma | |

| 203 | miR-656 | miR-656 | Lung | |

| 204 | miR-660 | miR-660 | Lung | |

| 213 | miR-876-3p | miR-876-3p | Lung | |

| 218 | miR-92 | miR-92 | Lung | |

| 221 | miR-939 | miR-939 | Lung | |

| 224 | miR-let-7 | let-7 | Lung | |

| Novel proteins | 3 | Haptoglobin | HP | Lung |

| 21 | CD9 | CD9 | Lung | |

| 22 | CD81 | CD81 | Lung | |

| 39 | HMGA1 | HMGA1 | Lung | |

| 40 | TFDP1 | TFDP1 | Lung | |

| 41 | SUV39H1 | SUV39H1 | Lung | |

| 42 | RBL1 | RBL1 | Lung | |

| 43 | HNRPD | HNRPD | Lung | |

| 58 | Anterior gradient 2 | AGR2 | Lung | |

| 63 | Pentraxin-3 | PTX3 | Lung | |

| 67 | Lysyl oxidase | LOX | Lung | |

| 75 | Death receptor 3 | DR3 | Lung | |

| 76 | Membrane-spanning 4 domain subfamily A from the multigene family of proteins involved in signal transduction of which CD20 is one member | MS4A | Lung | |

| 93 | Heat shock protein 90 alpha | HSP90alpha | Lung | |

| 94 | Leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domains 3 | LRIG3 | Lung | |

| 95 | Pleiotrophin | Pleiotrophin | Lung | |

| 96 | Protein kinase C iota type | PRKCI | Lung | |

| 97 | Repulsive Guidance Molecule C | RGM-C | Lung | |

| 98 | Stem Cell Factor soluble Receptor | SCF-sR | Lung | |

| 99 | YES | YES | Lung | |

| 116 | HMGB1 | HMGB1 | Mesothelioma | |

| 119 | Carbohydrate antigen 50 | CA50 | Lung | |

| 125 | Cytokeratin fragment 21.1 | Cytokeratin fragment 21.1 | Lung | |

| 126 | Serum amyloid A | SAA | Lung | |

| 128 | Carbohydrate antigen 211 | CA211 | Lung | |

| 146 | Endoplasmic reticulum protein-29 | ERP29 | Lung | |

| Nuclear proteins | 3 | Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 | IDH1 | Lung |

| 4 | p53 messenger RNA | p53 mRNA | Lung | |

| 10 | E2F6 | E2F6 | Lung | |

| 13 | Variant Ciz1 | Ciz1 | Lung | |

| Microbial proteins | 6 | Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene 3 | EBI3 | Lung |

| Volatile organic compounds | Nil | Nil |

3. Discussion

We systematically searched the literature from the last five years to identify potential blood biomarkers for cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011, Cree, 2011). The data mining process retrieved 3990 citations from the initial 19, 724 records, screening the abstracts of these citations identified 814 biomarkers that may be relevant. After data-cleaning, 788 biomarkers were fitted into 13 categories as described above as having potential for use as early cancer detection biomarkers present within blood samples. Biomarkers were grouped by molecular function. Further analysis such as grouping by cancer type may be possible only once the utility of each biomarker has been reviewed independently. As this is a mapping review, it is not possible to speculate the definitive clinical utility for each biomarker. Most studies reviewed tended to concentrate on single common cancers, and few papers show evidence of a systematic approach to biomarker discovery but were limited by the clinical samples and techniques of their laboratories.

The conduct of large systematic reviews is challenging, yet not all biomedical questions can be reduced to the size where standard methodologies for systematic review are thought reasonable. We have therefore taken a data mining approach to map blood biomarkers that may be suitable for the early detection of cancer using the search tools available within the reference management software. As with any approach to reviewing literature that falls short of a full systematic review, there is a balance between rigour and expenditure of time and resources. In this case, the aim was not to identify all relevant literature (as would be the case in a systematic review of efficacy), but rather all relevant biomarkers. It should be noted that the database does not hold the full text of the articles referenced and is restricted to titles, abstracts and keywords. Full text searching using machine learning algorithms could eventually provide a better solution.

In this instance, to allow a thorough search of the large dataset of biomarker literature and ensure an efficient approach to managing the data, we used data mining tools available within the reference management software. This allowed us to retrieve potentially relevant records, extract data relating to relevant biomarkers, and validate the process through adjunctive searches of reviews and through contact with an extensive network of experts. While the use of experts to validate the data may be regarded as subjective, it was a necessary step in validation of the searches and the multidisciplinary consortium involved in this work covers a large range of expertise. The limitation to studies published after 2009 could have skewed the data towards new technologies, and therefore reviews were included to mitigate the risk of ignoring older methodologies. Despite this limitation, it is notable that proteomic biomarkers, a more mature technology, formed a large proportion of the biomarkers found. Furthermore, it is possible that many of those biomarkers that have received less attention more recently did so because they were found to have limited utility in subsequent studies. We used conservative selection criteria that may have resulted in the inclusion of irrelevant biomarkers, but will have minimised the chance of relevant biomarkers being excluded. As such, we are confident that our methodology is fit for purpose and will have had high sensitivity for the identification of relevant biomarkers.

Limiting the mapping review to abstracts may have excluded studies identifying multiple potential biomarkers if such biomarkers were only mentioned in the main text. This is unlikely to occur in the field of emerging and promising biomarkers where the aim is to highlight the biomarker and technology to the audience. However, the vagueness of the abstracts of many papers is a challenge, as is the generally poor quality of study design. Even some larger scale studies from major groups do not include controls and few studies were powered to examine multiple biomarkers in comparison with existing tumour markers. The majority of cases (when described) are from patients with advanced disease, and this is a major concern for those interested in early detection: there is no guarantee that biomarkers identified in patients with advanced disease are relevant to those with early disease. There is certainly a need to improve the quality of papers on early detection using tools such as those available from the EQUATOR network (http://www.equator-network.org).

Our intention is to use the list of biomarkers identified by this review to generate a set of biomarkers that can be subjected to analytical validation within pathology blood science laboratories, then clinically validated within a large, prospective, multicentre clinical study to develop a generic cancer testing strategy for subsequent clinical trial. The primary aim is to produce a screening test strategy for cancer that does more good than harm at reasonable cost. Good includes decreased morbidity and mortality from early detection, diagnosis and treatment of cancers, while harm is usually regarded as significant risk of overdiagnosis, and consequent overtreatment. The entire strategy needs to be cost effective to achieve eventual approval from the UK National Screening Committee (NSC), which defines 22 criteria according to the condition, the test, the treatment and the screening programme (http://www.screening.nhs.uk/criteria) based on those developed by Wilson & Jungner (1968).

Within the list, there are some interesting results. Firstly, it is clear that current tumour markers, which considered in isolation, few would regard as sensible diagnostic tests in patients with a possible diagnosis of cancer, are collectively quite good at detection if used concurrently. The bulk of the work on this comes from one group in Barcelona (Molina et al., 2012), with other important contributions from others (Barak et al., 2010). The validation of biomarkers needs a point of reference, for direct comparison and it is clear that tumour marker lists used by Molina et al. (2012) represent such a standard. We would encourage those active in the field to use this list as their comparator for future work to allow comparison between studies.

The biomarkers can be grouped by the technology used for their detection. Taken to its logical conclusion, this results in a reduction of the thirteen groups above to seven groups as outlined in Box 3.

Box 3. Seven biomarker groupings based on technology used for detection.

Seven biomarker groupings 1. Existing tumour marker panels (current standard for comparison); 2. Auto-antibodies. 3. Circulating free DNA from the tumour (ctDNA); 4. Circulating MicroRNA (miRNA); 5. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC); 6. Mass Spectroscopy (MS); 7. Other biomarkers.

Alt-text: Box 3

The ability of protein measurement to be multiplexed by immunoassay arrays or mass spectroscopy means that all proteins, including auto-antibodies, can be measured simultaneously. Simple panels with few analyses tend to be less expensive and have greater potential for high throughput. DNA and RNA can be detected rapidly and inexpensively by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technologies, and there is evidence from multiple studies that the level of cfDNA has potential as a generic cancer marker. However, PCR is limited in the number of targets that can be detected at one time, and by the small amount of material present in patients with small tumours, which does not permit large numbers of tests to be performed without recourse to sequencing or large panels. Sequencing has the potential to detect large numbers of mutations, adding specificity, and could have utility in reflex testing. It is currently an expensive option, but costs of sequencing are decreasing rapidly, while technologies available are improving their capability at almost the same pace.

Metabolomics is of considerable interest, with a large literature to support it. While larger molecules require mass spectroscopy to measure their presence, smaller molecules can be detected in gas phase in the head space of blood samples using inexpensive sensor technologies. We believe that this relatively new option may have considerable potential to act as a generic test. There are a number of other tests that do not fit immediately into one of these seven categories: nucleosome assays are one such example, and are being used as potential screening tests.

The concept of combining high sensitivity/low specificity tests with reflex low sensitivity/high specificity tests to detect cancers early (Cree, 2011), seems feasible from the results we have obtained. We need to combine biomarkers with high sensitivity for screening the general population with biomarkers of high specificity to determine the relevance of the screening results. The next task is clearly to try this in practice to determine its real potential for early cancer detection, and to determine the best analytical methods to process the data for individual patients. Our preferred strategy is to examine the biomarkers in each category in greater detail, and undertake direct comparison of these biomarkers in a large cohort of samples following independent analytical validation. In our view, the same caveats around retrospective studies apply to biomarker validation as they do to drug trials: the potential for bias from sample collections is high and large prospective studies are necessary. This review is therefore the first step in an ambitious programme of work which will inevitably require careful evaluation of clinical, cost and ethical implications at each stage. However, there is no doubt that if such an approach to early cancer detection proved successful, it could be invaluable.

4. Conclusion

This ground-breaking study is the first to systematically and comprehensively map blood biomarkers for early detection of cancer and will inform an innovative research project to identify, validate and implement new generic blood screening tests for early cancer detection in the general population.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Adhesion and matrix proteins.

Auto-antibodies & immunological markers.

Classical tumour markers.

Coagulation and angiogenesis molecules.

Cytokines, chemokines and insulin-like growth factors.

Circulating-free DNA.

Hormones.

Metabolic markers.

MicroRNA and other RNAs.

Novel proteins.

Nuclear proteins.

Microbial proteins.

Volatile organic compounds.

Authors Contributions

IC, SH, BW, and STP designed the study. Searches were performed HBW. LU performed the mapping review with input from the ECDC. The draft manuscript was prepared by LU, IC and BW. All authors agreed the final version.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors LU, IC, SH, STP, BW, HBW have no conflicts of interest to declare. The ECDC has grant funding for early cancer biomarker research from Cancer Research UK and involves the following companies GE Healthcare, Life Technologies, Abcodia, Nalia, and Perkin-Elmer. Individual ECDC members have declared their interests to the ECDC secretariat.

Funding

This work was conducted on behalf of the Early Cancer Detection Consortium, within the programme of work for work packages 1 & 2. The Early Cancer Detection Consortium is funded by Cancer Research UK under grant number: C50028/A18554.

Box 2. Keywords used in data mining process.

Keywords used: “systematic review”; “metabolomics”; “ELISA”; “PCR”; “volatile organic compound”; “electronic”; “immunoassay”; “microRNA”; “early diagnosis”; RNA”; “biomarkers”; and “fluorescence”.

Alt-text: Box 2

References

- Barak V., Holdenrieder S., Nisman B., Stieber P. Relevance of circulating biomarkers for the therapy monitoring and follow-up investigations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2010;6(3–4):191–196. doi: 10.3233/CBM-2009-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beije N., Jager A., Sleijfer S. Circulating tumor cell enumeration by the CellSearch system: the clinician's guide to breast cancer treatment? Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015;41(2):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berruti A., Torta M., Piovesan A. Biochemical picture of bone metabolism in breast cancer patients with bone metastases. Anticancer Res. 1995;15(6B):2871–2875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy C., Joyce M.R., Kerin M.J. The use of circulating microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2014 doi: 10.3233/CBM-140456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane A.L., Holland W.W. Validation of screening procedures. Br. Med. Bull. 1971;27(1):3–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coco S., Truini A., Vanni I. Next generation sequencing in non-small cell lung cancer: new avenues toward the personalized medicine. Curr. Drug Targets. 2015;16(1):47–59. doi: 10.2174/1389450116666141210094640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couraud S., Vaca-Paniagua F., Villar S. Noninvasive diagnosis of actionable mutations by deep sequencing of circulating free DNA in lung cancer from never-smokers: a proof-of-concept study from BioCAST/IFCT-1002. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(17):4613–4624. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree I.A. Improved blood tests for cancer screening: general or specific? BMC Cancer. 2011;11:499. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross A.J., Moore S.C., Boca S. A prospective study of serum metabolites and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer. 2014;120(19):3049–3057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling P., Clarke C., Hennessy K. Analysis of acute-phase proteins, AHSG, C3, CLI, HP and SAA, reveals distinctive expression patterns associated with breast, colorectal and lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;131(4):911–923. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni R., Urban N., Ramsey S. The case for early detection. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3(4):243–252. doi: 10.1038/nrc1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortunato O., Boeri M., Verri C. Assessment of circulating microRNAs in plasma of lung cancer patients. Molecules. 2014;19(3):3038–3054. doi: 10.3390/molecules19033038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gires O., Stoecklein N.H. Dynamic EpCAM expression on circulating and disseminating tumor cells: causes and consequences. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71(22):4393–4402. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1693-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov P., Gromova I., Bunkenborg J. Up-regulated proteins in the fluid bathing the tumour cell microenvironment as potential serological markers for early detection of cancer of the breast. Mol. Oncol. 2010;4(1):65–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasim A., Aili A., Maimaiti A., Mamtimin B., Abudula A., Upur H. Plasma-free amino acid profiling of cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia patients and its application for early detection. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;40(10):5853–5859. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2691-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauselmann I., Borsig L. Altered tumor-cell glycosylation promotes metastasis. Front Oncol. 2014;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdenrieder S., Dharuman Y., Standop J. Novel serum nucleosomics biomarkers for the detection of colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34(5):2357–2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y.M. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum: an overview. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;945:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y.M. Quantitative analysis of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in plasma and serum: applications to tumor detection and monitoring. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;945:68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig N., Keller A., Heisel S. Improving seroreactivity-based detection of glioma. Neoplasia. 2009;11(12):1383–1389. doi: 10.1593/neo.91018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail S., Johnson S., Greenberg D., Peake M., Rous B. Stage at diagnosis and early mortality from cancer in England. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112(Suppl. 1):S108–S115. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton C.H., Irving W., Robertson J.F. Serum autoantibody measurement for the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina R., Bosch X., Auge J.M. Utility of serum tumor markers as an aid in the differential diagnosis of patients with clinical suspicion of cancer and in patients with cancer of unknown primary site. Tumour Biol. 2012;33(2):463–474. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson C.R., Robins S.P., Horobin J.M., Preece P.E., Cuschieri A. Pyridinium crosslinks as markers of bone resorption in patients with breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 1991;64(5):884–886. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe F., Laes J.F., Lambrechts D. Plasma circulating tumor DNA as an alternative to metastatic biopsies for mutational analysis in breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25(10):1959–1965. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R., Yang J., Moses M.A. Matrix metalloproteinases as novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(31):5287–5297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter G.B., Lopes J.D. Two-site immunoassays for the measurement of serum laminin: correlation with breast cancer staging and presence of auto-antibodies. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Med. Biol. Soc. Bras. de Biofisica. 1990;23(2):141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J.M., Jungner Y.G. Principles and practice of mass screening for disease. Bol. Of Sanit Panam. Pan Am. Sanit. Bur. 1968;65(4):281–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A.M., Wender R.C., Etzioni R.B. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010;60(2):70–98. doi: 10.3322/caac.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Xie X., Liu Y. Identification and confirmation of differentially expressed fucosylated glycoproteins in the serum of ovarian cancer patients using a lectin array and LC-MS/MS. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11(9):4541–4552. doi: 10.1021/pr300330z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Adhesion and matrix proteins.

Auto-antibodies & immunological markers.

Classical tumour markers.

Coagulation and angiogenesis molecules.

Cytokines, chemokines and insulin-like growth factors.

Circulating-free DNA.

Hormones.

Metabolic markers.

MicroRNA and other RNAs.

Novel proteins.

Nuclear proteins.

Microbial proteins.

Volatile organic compounds.