Abstract

Objectives

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects people across the age spectrum and is highly comorbid with other medical conditions. The aim of this study was to determine the moderating effect of age on the relationship between medical comorbidity and health outcomes in IBS patients.

Methods

Patients (n = 384) across the age spectrum (18 to 70) completed questionnaires regarding medical comorbidities, anxiety, depression, IBS symptom severity, and IBS quality of life (QOL).

Results

The mean age was 41 (SD =15). Age interacted with medical comorbidities to predict anxiety, F(7,354) = 5.82, p = .009, R2 =.10. Results revealed significant main effects for education, β = −.16, p < .05, age, β = −.15, p < .05, medical comorbidities, β = .25, p < .05, and a significant interaction, β = −.15, p < .01. Anxiety was greater among patients with many comorbidities, with this effect being more pronounced for younger adults. Depression, also predicted by the interaction between age and comorbidities, showed the same pattern as anxiety. There was no significant interaction between age and medical comorbidities in predicting IBS symptom severity or IBS QOL.

Conclusion

Distress among IBS patients with medical comorbidities varies with age, with higher levels of anxiety and depression among younger adults than their older counterparts. Medical comorbidity may have a more selective impact on psychological distress as compared to IBS symptom severity and quality of life for younger adults with IBS. Distress may increase IBS burden for these patients and complicate its medical management.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, IBS symptom severity, IBS QOL, Anxiety, Depression, Medical Comorbidity

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and potentially disabling disorder that afflicts approximately 25 million Americans. Individuals aged 25–54 [1] have higher rates of IBS than other age groups, causing IBS to often be regarded as a “young person’s disease.” However, recent studies suggest that IBS is more common among older individuals than previously believed [2;3]. The lower prevalence of IBS among older adults may be a function of low sensitivity of diagnostic criteria in this age group [4]. Another factor that may influence detection of IBS is the higher prevalence of medical comorbidities among older adults [3]. Amid a variety of medical problems, IBS may not be considered clinically meaningful or may be thought to be part of the natural course of aging.

Medical comorbidity among patients with IBS may not only present a unique diagnostic challenge for clinicians but also may pose a significant burden on patients. Although individuals with IBS and medical comorbidities tend to have worse health outcomes than those with IBS alone [5], the impact of medical comorbidity among older adults with IBS has not been specifically examined. This is an important area of research, given that the older population in the United States is growing rapidly, with those aged 65 and older projected to be 83.7 million in 2050, almost double the rates of 43.1 million seen in 2012 [6]. Adverse effects of IBS may be amplified in older adults because of the additive effect of multiple medical problems; however, little is known about how age influences the association between medical comorbidity and health outcomes in patients with IBS.

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of age on the relationship between number of medical comorbidities and clinically relevant health outcomes in a cohort of severely affected IBS patients. We hypothesized that the relationship between number of medical comorbidities and IBS symptom severity, anxiety, depression, and quality of life would be moderated by age, with older adults experiencing greater IBS symptom severity, higher levels of anxiety and depression, and a lower quality of life than their younger counterparts.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

This study is a secondary analysis of a larger National Institutes of Health clinical trial of behavioral treatments for IBS. Patients were recruited primarily through local media coverage and community advertising and referral by physicians in surrounding areas to tertiary care clinics at two academic medical centers in Buffalo, NY, and Chicago, IL. After a brief telephone interview to determine whether interested individuals were likely to meet basic inclusion criteria, patients were scheduled for a medical examination to confirm a Rome III diagnosis of IBS [7], written signed consent was obtained, and psychometric testing was conducted. Eligibility criteria are described more fully elsewhere [5]. Participants (n = 384) were primarily Caucasian (89.5%) and female (79.9%) and were represented across the age spectrum (range: 18 to 70 years), with a mean age of 41. Institutional review board approval (UB, May 19, 2009; NU, December 19, 2008) was obtained.

Measures

For the purposes of this study, psychometric testing used the following psychometrically validated measures.

Patient Characteristics

Information was obtained via self-report on participants’ age at the time of presentation (in years), gender, race, marital status, income (in thousands of dollars), education, IBS subtype (IBS-constipation, IBS-diarrhea, IBS-mixed, IBS-undifferentiated), duration of symptoms (years), age symptoms began (years), number of recent medical visits (past 3 months), and recent physician visit (yes and no).

IBS Medical Comorbidity

Medical comorbidity was assessed using a comorbidity checklist that covers 112 medical conditions organized around 12 body systems (musculoskeletal, digestive, kidney/genitourinary, endocrine, respiratory, circulatory, cardiovascular, oral, CNS, dermatological, cancer, ear, nose and throat) [8]. Respondents were asked whether a physician had ever diagnosed them with a condition and, if so, whether the condition was present in the past 3 months. A total score was based on the number of medical comorbidities a patient reported.

Anxiety and Depression

Psychological distress was assessed using the 18-item version of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) [9], which has been used extensively in IBS research [10]. Respondents indicated their level of distress on a five-point scale, 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). In this study, we analyzed the anxiety and depression subscales. Internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity of the BSI-18 are well-established [9].

IBS Symptom Severity

The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Symptom Severity Scale [11] contains five questions measured on a 100-point scale, examining severity of abdominal pain, frequency of abdominal pain, severity of abdominal distension, dissatisfaction with bowel habits, and interference with quality of life. The number of days out of 10 the patient experiences abdominal pain is asked by a final item, and the answer is multiplied by 10. All five items are summed to create a total score (range: 0 – 500), and scores ranging from 75 – 175 represent mild severity, scores ranging from 175 – 300 represent moderate severity, and a score of 300 or greater represents severe IBS symptoms [11].

IBS Quality of Life

The 34-item IBS-QOL measure [12] evaluates quality of life impairment due to IBS symptoms. Each item is scored on a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = a great deal) that represents one of eight dimensions (dysphoria, interference with activity, body image, health worry, food avoidance, social reaction, sexual dysfunction, and relationships). An overall total score of IBS-related quality of life is transformed to a scale ranging from zero (poor quality of life) to 100 (maximum quality of life).

Statistical Analyses

To determine the relationship between demographic and clinical characteristics, we examined patient characteristics, based on age, number of medical comorbidities, anxiety and depression, IBS symptom severity and IBS quality of life.

Pearson correlations were used to examine the association between age and each of the following: number of medical comorbidities, IBS symptom severity, depression, anxiety, and IBS quality of life. To identify potential confounding variables, these variables were examined as they related to patient characteristics, using independent samples t-tests or analyses of variance and Pearson product moment correlations.

Moderated multiple linear regression analyses were conducted to examine whether age interacted with medical comorbidity to predict anxiety, depression, IBS symptom severity, and quality of life. The models were constructed in two steps. Step one included any significant covariates from the previous analyses. Step two included all predictors from step one with the main effects of age and the number of medical comorbidities. Step two also included all predictors from step one, with the addition of the interaction term between age and the number of medical comorbidities. If a significant interaction is found, it means that the relationship of the predictor (number of medical comorbidities) on the outcome (anxiety, depression, symptom severity, or quality of life) differs, based on the moderator (age) of the patient. The shape of any significant interactions between number of medical comorbidities and age was examined by plotting the predicted variables for the dependent variable at one standard deviation above and below the mean for both variables involved in the interaction [13]. A power analysis for our test of the interaction effect with our sample size (n = 384) and an alpha level set at .05 resulted in estimates of 80% power for a 2% increase in variance in the dependent measures accounted for, and a 92% power for a 3% increase in variance accounted for in our analyses.

Results

Characteristics of Study Sample

The distribution of age, number of medical comorbidities, and health outcomes (anxiety, depression, IBS symptom severity, and IBS quality of life), across demographic and clinical features is presented for all participants (Table 1). Patients reported moderate-to-severe IBS (IBS-SSS range: 106–473) with symptoms that were present for many years (M = 16.29 years, SD = 14.08 years). Medical comorbidities were prevalent in the study population, with a range from 0 to 32 comorbidities. The most common medical comorbidity experienced was seasonal allergies (49%), followed by gastroesophageal reflex disease/heartburn (40%), and chronic low back pain (29%). Overall, patients experienced high levels of anxiety (M = 4.73, SD = 4.68) and depression (M = 4.13, SD = 4.39) and a low IBS-related quality of life (M = 56.32, SD = 18.23).

Table 1.

Distribution of Age at Presentation, Medical Comorbidity, and Health Outcomes, Based on Several Demographic and Clinical Features (N=384)

| Age | Comorbidity | Anxiety | Depression | Symptom Severity | Quality of Life | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | N | ||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 42 (15) | 7(6) | 5.55 (5.18) | 4.64 (4.51) | 267.80 (66.18)* | 56.68 (17.69) | 77 | |

| Female | 41 (16) | 8 (6) | 4.53 (4.54) | 4.01 (4.36) | 286.79 (72.97) | 56.23 (18.39) | 307 | |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 41 (15) | 8 (6) | 4.77 (4.68) | 3.97 (4.25)* | 281.51 (70.22) | 56.52 (18.10) | 344 | |

| Non-White | 43 (16) | 10 (8) | 4.34 (4.79) | 5.07 (5.28) | 296.59 (85.88) | 54.49 (19.50) | 32 | |

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Not Married | 38 (15)* | 8 (7) | 4.93 (4.66) | 4.48 (4.59)* | 280.96 (70.67) | 56.57 (17.91) | 224 | |

| Married | 46 (13) | 8 (6) | 4.44 (4.73) | 3.58 (4.04) | 286.42 (73.95) | 55.73 (18.55) | 159 | |

| Income1 | ||||||||

| Below $62.5K | 41 (15) | 9 (7)* | 5.11 (4.87) | 4.61 (4.70)* | 281.78 (74.23) | 55.37 (18.47) | 223 | |

| Above $62.5K | 41 (14) | 7 (5) | 4.33 (4.49) | 3.58 (3.94) | 286.09 (68.64) | 56.85 (17.97) | 146 | |

| Education | ||||||||

| High school | 44 (16)* | 9 (7)* | 5.64 (5.45)* | 5.32 (5.23)* | 293.82 (81.17)* | 51.93 (19.84) | 140 | |

| College | 39 (14) | 7 (6) | 4.22 (4.11) | 3.44 (3.66) | 276.93 (65.62) | 58.86 (16.82)* | 244 | |

| IBS Subtype2 | ||||||||

| IBS-C | 42 (14) | 8 (6) | 4.59 (4.73) | 4.51 (4.27) | 295.96 (72.22) | 55.44 (18.28) | 109 | |

| IBS-D | 42 (15) | 8 (6) | 4.42 (4.19) | 3.73 (4.10) | 276.77 (74.37) | 56.94 (19.17) | 165 | |

| IBS-M | 38 (15) | 8 (7) | 5.62 (5.48) | 4.57 (4.94) | 279.19 (68.16) | 55.67 (16.86) | 91 | |

| IBS-U | 40 (17) | 6 (7) | 4.17 (4.25) | 3.50 (4.71) | 283.61 (64.26) | 59.19 (17.18) | 18 | |

| Duration of Symptoms1 | ||||||||

| 12 Years or Less | 35 (14)* | 7 (5)* | 4.84 (4.79) | 4.07 (4.38) | 284.31 (74.38) | 55.63 (18.07) | 192 | |

| Over 12 Years | 47 (14) | 9 (7) | 4.64 (4.61) | 4.14 (4.41) | 280.46 (68.47) | 57.31 (18.32) | 184 | |

| Age of Symptom Onset1 | ||||||||

| Age 21 or under | 35 (14)* | 7 (6) | 4.84 (4.81) | 3.95 (4.52) | 285.68 (65.56) | 54.53 (18.02)* | 196 | |

| Over age 21 | 47 (13) | 9 (7) | 4.64 (4.59) | 4.27 (4.25) | 278.80 (77.57) | 58.84 (18.18) | 180 | |

| Seen physician recently | ||||||||

| No | 40 (15) | 6 (5)* | 4.64 (4.59) | 3.85 (4.09) | 272.35 (68.35) | 58.82 (18.08) | 73 | |

| Yes | 42 (15) | 8 (7) | 4.76 (4.72) | 4.19 (4.46) | 285.51 (72.69) | 55.74 (18.24) | 311 | |

NOTE:

p < .05,

For descriptive purposes of the table, a median split was conducted on income, duration of symptoms, and age of symptom onset; however, in all other analyses these variables were treated as continuous variables.

IBS - C, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation; IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome diarrhea; IBS-M, irritable bowel syndrome, mixed; IBS-U, irritable bowel syndrome, undifferentiated.

Correlations Between Demographics, Medical Comorbidity, and Health Outcomes

Pearson product-moment correlations (Table 2) indicated that age was positively correlated with the number of medical comorbidities, symptom duration, and with quality of life but not with depression, anxiety or symptom severity. Number of medical comorbidities was correlated negatively with income, and positively with symptom duration and the number of recent medical visits. It was also positively correlated with anxiety, depression, and symptom severity, and negatively correlated with quality of life. In addition, higher anxiety was associated with lower income, more depression, greater symptom severity, and lower quality of life. Higher levels of depression were associated with greater symptom severity and a lower quality of life. Symptom severity and quality of life were also negatively correlated.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. Age Symptoms Began | .52** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. Income | .00 | .04 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. Symptom Duration | .53** | −.44** | −.05 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. Medical Visits | .01 | −.03 | −.08 | .05 | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. Comorbidities | .40** | .07 | −.20** | .35** | .26** | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. Depression | .02 | .02 | −.15** | −.01 | .10 | .21** | 1.00 | |||

| 8. Anxiety | −.05 | −.04 | −.11* | −.01 | .06 | .17** | .68** | 1.00 | ||

| 9. Symptom Severity | −.08 | −.07 | −.01 | −.02 | .09 | .11* | .22** | .17** | 1.00 | |

| 10. Quality of Life | .11* | −.10 | .05 | .03 | −.15** | −.15** | −.43** | −.37** | .46** | 1.00 |

p < .05;

p < .01

Characteristics of Age, Medical Comorbidity, and Health Outcomes Across Demographic and Clinical Features

As is presented in Table 1, women reported significantly higher symptom severity than did men, t (379) = −2.06, p = .040, and nonwhite patients reported higher levels of depression, t (376) = −2.10, p = .036. Married patients were significantly older, t (381) = − 5.08, p > .001, and those not married scored higher on depression, t (375) = 1.97, p = .049. Those with only a high school education were significantly older, t (382) = 2.86, p = .004, had a greater number of medical comorbidities, t (380) = 3.46, p = .001, scored higher on anxiety, t (376) = 2.86, p = .004, depression, t (3.76) = 4.09, p < .001 and symptom severity, t (379) = 2.21, p = .028, and lower on quality of life, t (380) = −3.63, p < .001.

Age as a Moderator between Medical Comorbidity and Health Outcomes

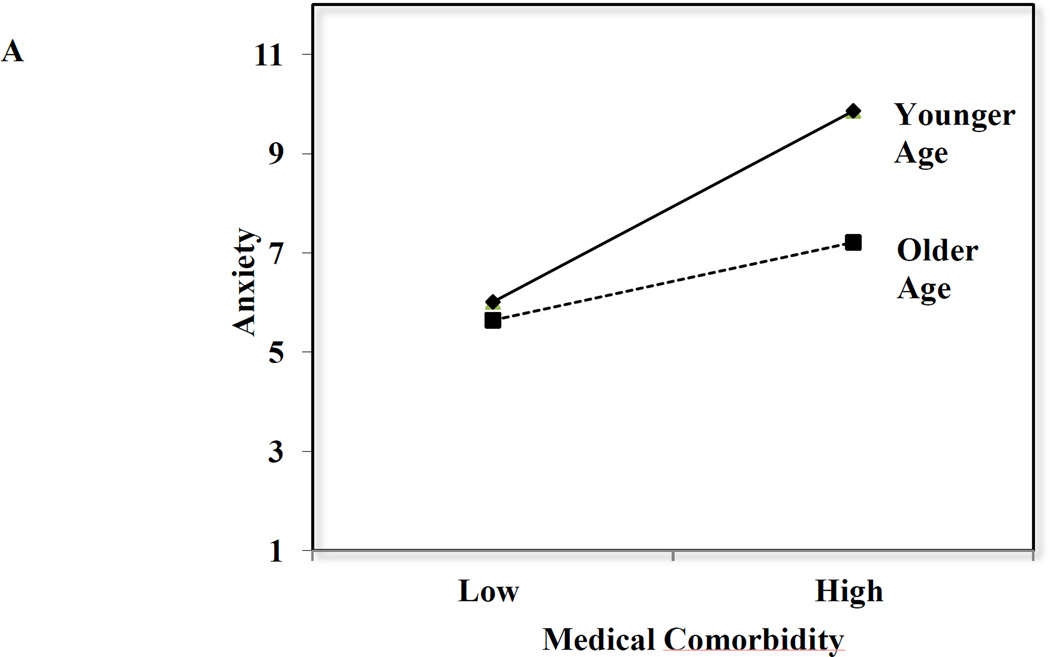

The first series of multiple linear regression models examined the relationship between anxiety (outcome), age (moderator), and medical comorbidities (predictor) (Table 3). In step one, the model was significant, F (6, 355) = 5.56, p < .001 and predicted 9% of the variance in anxiety. Education, β = −.15, p = .004; age, β = −.16, p =.008; and medical comorbidities, β = .20, p = .001, were significant predictors of anxiety. In step two, the interaction term between age and the number of medical comorbidities significantly added to the amount of variance in the criterion accounted for in the model, ΔR2 = .02 ΔF(1,354) = 6.86, p = .009; and the interaction term significantly predicted anxiety, β = −.15, p = .009. Examination of the shape of the interaction (Figure 1A) indicated there was no significant effect of age on anxiety for patients with fewer comorbid disorders. However, anxiety was greater among patients with many medical comorbidities, with this effect being more pronounced for younger IBS patients.

Table 3.

Results of Multiple Linear Regression Models Relating Anxiety, Depression, Symptom Severity, and Quality of Life (Outcomes) to Age (Moderator) and Medical Comorbidities (Predictor).

| Models | B(SE) | β | F | R2 | Adj. R2 | ΔR2 | F-change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | ||||||||

| Step 1 | F (6,355)= 5.56** | .09 | .07 | -- | ---- | |||

| Constant | 10.44 (1.53)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | −1.03 (0.35)** | −.15 | ||||||

| Income | −0.01 (0.01) | −.06 | ||||||

| Married | 0.11 (0.57) | −.01 | ||||||

| Gender | −1.19 (0.62) | −.10 | ||||||

| Age | −0.05 (0.02)** | −.16 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 0.14 (0.04)** | .20 | ||||||

| Step 2 | F (7,354)= 5.82** | .10 | .09 | .02 | F(1,354)=6.86** | |||

| Constant | 11.24 (1.55)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | −1.04 (0.35)** | −.16 | ||||||

| Income | −0.01 (0.01) | −.07 | ||||||

| Married | −0.08 (0.57) | −.01 | ||||||

| Gender | −1.28 (0.61) | −.12 | ||||||

| Age | −0.05 (0.02)** | −.15 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 0.19 (0.04)** | .25 | ||||||

| Age*medical comorbidities | −0.01 (0.01)* | −.15 | ||||||

| Depression | ||||||||

| Step 1 | F (6,355)= 6.30** | .10 | .08 | -- | ---- | |||

| Constant | 9.44 (1.43)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | −1.05 (0.33)** | −.17 | ||||||

| Income | −0.01 (0.01) | −.06 | ||||||

| Married | −0.49 (0.52) | −.05 | ||||||

| Gender | −0.81 (0.58) | −.10 | ||||||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −.16 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 0.14 (0.04)** | .21 | ||||||

| Step 2 | F (7,354)= 7.58** | .13 | .11 | .03 | F(1,354)=13.89** | |||

| Constant | 10.48 (1.44)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | −1.07 (0.33)** | −.16 | ||||||

| Income | −0.01 (0.01) | −.08 | ||||||

| Married | −0.73 (0.52) | −.08 | ||||||

| Gender | −1.05 (0.57) | −.09 | ||||||

| Age | −0.02 (0.02) | −.07 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 0.19 (0.04)** | .28 | ||||||

| Age*medical comorbidities | −0.02 (0.01)** | −.21 | ||||||

| Symptom Severity | ||||||||

| Step 1 | F (6,358)= 3.150** | .05 | .03 | -- | ||||

| Constant | 239.30 (23.80)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | 3.82 (5.51) | .04 | ||||||

| Income | −0.06 (0.08) | −.04 | ||||||

| Married | 18.41 (8.75)* | .13 | ||||||

| Gender | 16.03 (9.52) | .09 | ||||||

| Age | −0.80 (0.29)** | −.16 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 2.04 (0.65)** | .18 | ||||||

| Step 2 | F (7,357)= 2.73** | .05 | .03 | .00 | F(1,357)=0.25 | |||

| Constant | 241.71 (24.32)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | 3.78 (5.51) | .04 | ||||||

| Income | −0.06 (0.09) | −.04 | ||||||

| Married | 17.85 (8.82)* | .12 | ||||||

| Gender | 15.47 (9.59) | .09 | ||||||

| Age | −0.81 (0.29)** | −.16 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | 2.17 (0.69)** | .19 | ||||||

| Age*medical comorbidities | −0.02 (0.04) | −.03 | ||||||

| Quality of Life | ||||||||

| Step 1 | F (6,359)= 5.06** | .08 | .06 | -- | --- | |||

| Constant | 46.95 (5.86)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | 3.37 (1.36)* | .13 | ||||||

| Income | 0.01 (0.02) | .04 | ||||||

| Married | −4.40 (2.18)* | −.12 | ||||||

| Gender | −0.32 (2.34) | −.01 | ||||||

| Age | 0.26 (0.07)** | .21 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | −0.61 (0.16)** | −.22 | ||||||

| Step 2 | F (7,358)= 4.34** | .08 | .06 | .00 | F(1,358)=0.09 | |||

| Constant | 45.59 (5.98)** | --- | ||||||

| Education | 3.37 (1.36)* | .13 | ||||||

| Income | 0.01 (0.02) | .04 | ||||||

| Married | −4.32 (2.19)* | −.12 | ||||||

| Gender | −0.24 (2.36) | −.01 | ||||||

| Age | 0.26 (0.07)** | .21 | ||||||

| medical comorbidities | −0.62 (0.17)** | −.22 | ||||||

| Age*medical comorbidities | 0.00 (0.01) | .02 | ||||||

Note:

p < .05,

p <.01.

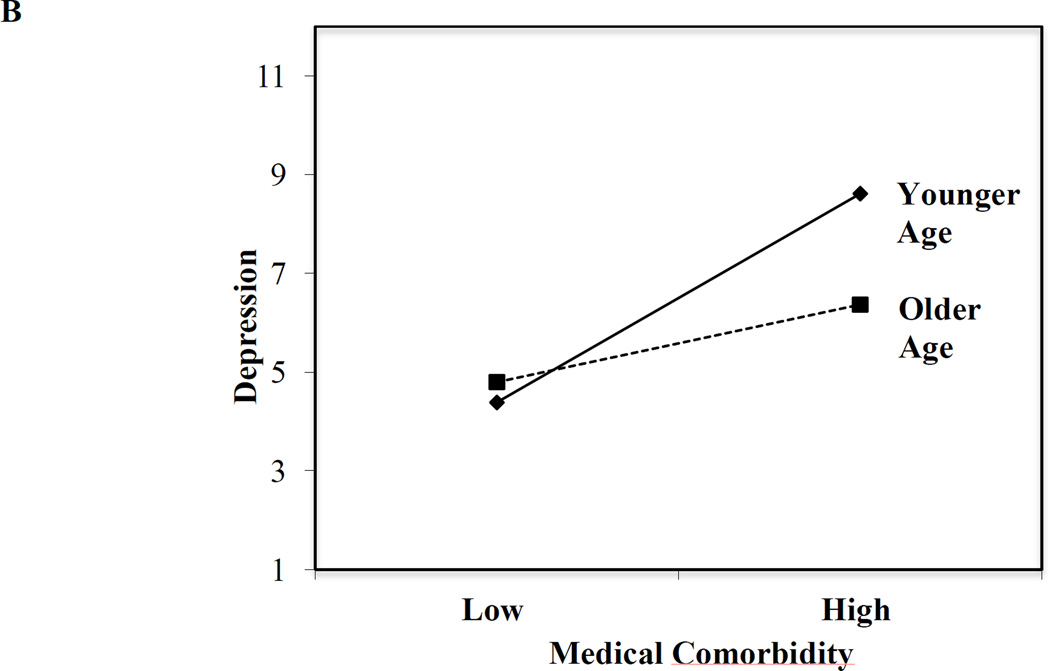

Figure 1.

Age as a Moderator of the Relationship between Number of Medical Comorbidities and Distress Scores for Anxiety (1A) and Depression (1B). Medical comorbidity and age values represented in the figure were calculated at one standard deviation below the mean (low) and one standard deviation above the mean (high). Medical comorbidity (M = 7.91, SD = 6.42) is shown for low (1.49) and high (14.33) values. Age (M = 41.18, SD = 14.80) is shown for younger (26.38) and older (55.98) age.

A similar analysis was also conducted to predict depression (Table 3). In the first step, the model accounted for a significant amount of variance in depression, R2 =.10 F(6,355)= 6.30, p < .001. Education β = −.17, p = 002, and medical comorbidities, β = .21, p < .001, were significant predictors of depression. Including the interaction term in step 2 significantly added to the amount of variance accounted for in depression, ΔR2 = .03 ΔF(1,354) = 13.89, p < .001 and the interaction term significantly predicted depression, β = −.21, p < .001. Inspection of the shape of the interaction (Figure 1B) indicated no significant effect of age on depression for patients with fewer comorbid disorders. However, depression was greater among patients with many medical comorbidities, with a greater effect for younger IBS patients.

The model for IBS symptom severity was also significant, R2 =.05 F(6,358) = 3.15, p = .005. Marital status, β = .13, p = .036, age, β = −.16, p = .005, and medical comorbidities, β = .18, p = .002, significantly predicted symptom severity. Addition of the interaction term between age and the number of medical comorbidities in step 2 did not account for an additional significant amount of variance in symptom severity, ΔR2 = .00 ΔF (1,357) = 0.25, p < .619. Similarly, when quality of life was used as the criterion variable, the main-effects model was significant, R2 = .07, F(6,359) = 5.06, p < .001. Education, β = .13, p = .013, marital status, β = −.12, p = .044, age, β = .21, p < .001, and medical comorbidities, β = −.22, p < .001, were all significant predictors of quality of life. Addition of the interaction term between age and the number of medical comorbidities in step 2 did not account for an additional significant amount of variance in quality of life, ΔR2 = .00 ΔF(1,358) = 0.09, p = .763.

Discussion

This study sought to assess the moderating relationship between age and number of medical comorbidities and IBS symptom severity, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in a sample of patients with severe IBS. We expected older IBS patients with multiple medical problems to experience worse health outcomes (i.e., greater IBS symptom severity, higher levels of anxiety and depression, and a lower quality of life) than younger adults with the disorder. Contrary to our expectations, we found younger IBS patients with more medical comorbidities to be more distressed than their older counterparts. In addition, the effect of medical comorbidity on health status was most pronounced for mental well-being (anxiety, depression) rather than IBS symptom severity and/or quality and life.

Our findings suggest that medical comorbidity may have a more selective impact on psychological distress (anxiety, depression) as compared to other health outcomes (i.e., IBS symptom severity, quality of life) for younger adults with IBS. Although this finding is somewhat counterintuitive, it echoes previous research that has shown psychological distress to be more common in young adulthood [14;15]. Medical comorbidities may not be perceived as manageable among younger patients, who often face multiple roles and responsibilities, have less experience with life stressors, and may be less prepared to cope. Conversely, older adults might adjust more readily because they regard multiple medical problems as a normative part of the aging process [16].

Our findings are of particular importance given that psychological distress may increase the daily burden of IBS, and complicate medical management, especially for younger IBS patients with significant medical comorbidities. Clinicians should be sensitive to the unique burden that affects younger patients with IBS. Pharmacological (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) or behavioral therapies, such as cognitive and behavioral therapy [17;18], may relieve emotional distress of residual symptoms that are not addressed through conventional treatment approaches. As patients gain control of their distress, they may be better able to manage gastrointestinal symptoms and their impact. However, additional research is needed to make more definitive clinical recommendations. Future studies should focus on identifying the role of specific cognitive and behavioral processes on the etiology and course of IBS to best direct clinical care.

These data should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. Our study was cross-sectional; therefore, we cannot infer causation. In addition, for the statistical models with significant interaction effects predicting anxiety and depression, the complete model accounted for a small amount of variance (i.e., 10%) in the dependent measures; given the multiple testing, some of these finding may be due to chance. Traditionally, effect size as expressed in variance accounted for in non-experimental psychosocial research tend to only range from 10% to 30%; however, when dealing with outcomes involving psychological distress such as anxiety and depression, even small effects may have important ramifications for the quality of patients’ lives [19]. Furthermore, our cross-sectional data is a snapshot of what may be indicative of a more cumulative effect [20] over time of medical comorbidity on anxiety and depression in IBS patients. A more comprehensive examination that examines the effects of comorbidity over time may have a greater impact and should be tested in a future longitudinal design. Our study also reflects a subset of treatment-seeking individuals with severe IBS who enrolled in a randomized controlled trial; therefore, these results may not generalize to patients from primary care settings, or nonconsulters in the community. We also focused on a limited number of variables believed to be associated with medical comorbidities in patients with IBS. Other factors may have contributed to the pattern of age differences that was found.

Despite these limitations, our study highlighted the importance of considering age when evaluating and treating patients with IBS and comorbid medical problems. Younger patients with IBS experience greater distress than their older counterparts, which may increase the daily burden of IBS and further complicate its medical management. Future epidemiological research with more diverse samples and a longitudinal design may add to our understanding of the influence age has on the relationship between medical comorbidities and health outcomes for patients with IBS.

Highlights.

IBS affects people of all ages and is comorbid with several medical conditions.

Medical comorbidities affect psychological distress in patients with IBS.

Medical comorbidities impact psychological distress more for younger IBS patients.

Psychological distress may increase IBS burden and complicate treatment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the IBSOS Research Group (Laurie Keefer, Darren Brenner, Rebecca Firth, Jim Jaccard, Leonard Katz, Susan Krasner, Christopher Radziwon, Michael Sitrin, Ann Marie Carosella, Chang-Xing Ma) for their assistance on various aspects of the research reported in the manuscript.

Financial Support: This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant DK77738 and was partially supported by the facilities and resources of the Houston VA HSR&D Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13–413). This research was also supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, the Department of Veterans Affairs South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the US government or Baylor College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing interests to report.

References

- 1.Hungin APS, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2005;21:1365–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal A, Khan MH, Whorwell PJ. Irritable bowel syndrome in the elderly: An overlooked problem? Digestive and Liver Disease. 2009;41:721–724. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehrenpreis ED. Irritable bowel syndrome. 10% to 20% of older adults have symptoms consistent with diagnosis. Geriatrics. 2005;60:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: symptom subgroups, risk factors, and health care utilization. American journal of epidemiology. 1995;142:76–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lackner JM, Keefer L, Jaccard J, Firth R, Brenner D, Bratten J, Dunlap LJ, Ma C, Byroads M IBSOS Research Group. The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study (IBSOS): Rationale and design of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 12month follow up of self-versus clinician-administered CBT for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Contemporary clinical trials. 2012;33:1293–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. pp. 25–1140. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480–1491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lackner JM, Ma C, Keefer L, Brenner DM, Gudleski GD, Satchidanand N, Firth R, Sitrin MD, Katz L, Krasner SS. Type, rather than number, of mental and physical comorbidities increases the severity of symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2013;11:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 18. Minneapolis: National Computer System; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn SD, Kaptchuk TJ, Park JB, Nguyen LT, Canenguez K, Nam BH, Woods KB, Conboy LA, Stason WB, Lembo AJ. A meta-analysis of the placebo response in complementary and alternative medicine trials of irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2007;19:630–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1997;11:395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patrick DL, Drossman DA, Frederick IO. A quality of life measure for persons with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-QOL): user's manual and scoring diskette for United States version. Seattle: University of Washington; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piazza JR, Charles ST, Almeida DM. Living with chronic health conditions: Age differences in affective well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007;62:313–321. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarkisian CA, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Do older adults expect to age successfully? The association between expectations regarding aging and beliefs regarding healthcare seeking among older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1837–1843. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laird KT, Tanner-Smith EE, Russell AC, Hollon SD, Walker LS. Short- and Long-Term Efficacy of Psychological Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, Soffer EE, Spiegel BM, Moayyedi P. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2014;109:1350–1365. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:532. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abelson RP. A variance explanation paradox: When a little is a lot. Psychological bulletin. 1985;97:129. [Google Scholar]