Abstract

PURPOSE: It deserves investigation whether induction chemotherapy (IC) followed by intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) is inferior to the current standard of IMRT plus concurrent chemotherapy (CC) in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. METHODS: Patients who received IC (94 patients) or CC (302 patients) plus IMRT at our center between March 2003 and November 2012 were retrospectively analyzed. Propensity-score matching method was used to match patients in both arms at equal ratio. Failure-free survival (FFS), overall survival (OS), distant metastasis–free survival (DMFS), and locoregional relapse–free survival (LRFS) were assessed with Kaplan-Meier method, log-rank test, and Cox regression. RESULTS: In the original cohort of 396 patients, IC plus IMRT resulted in similar FFS (P = .565), OS (P = .334), DMFS (P = .854), and LRFS (P = .999) to IMRT plus CC. In the propensity-matched cohort of 188 patients, no significant survival differences were observed between the two treatment approaches (3-year FFS 80.3% vs 81.0%, P = .590; OS 93.4% vs 92.1%, P = .808; DMFS 85.9% vs 87.7%, P = .275; and LRFS 93.1% vs 92.0%, P = .763). Adjusting for the known prognostic factors in multivariate analysis, IC plus IMRT did not cause higher risk of treatment failure, death, distant metastasis, or locoregional relapse. CONCLUSIONS: IC plus IMRT appeared to achieve comparable survival to IMRT plus CC in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Further investigations were warranted.

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignancy relatively rare in Europe and the United States [1] but highly endemic in Southern China [2] and Hong Kong [3]. Radiotherapy is the cornerstone of initial treatment. Since the publication of INT-0099 trial [4], several subsequent trials [5], [6], [7], [8], [9] have substantiated the survival benefits of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, which was consequently recommended as the standard of care in the subgroup of locoregionally advanced disease.

Interestingly, induction chemotherapy (IC) followed by two-dimensional conventional radiotherapy (2DCRT) alone was once reported to obtain encouraging response rates and improvement in disease-free survival (DFS) [10], [11], [12], [13]. It is expected to regress tumor extension, avoid irradiation of organs at risk, prevent tumor progression due to the long waiting time before radiotherapy, and finally improve local and distant control. Actually, benefit has been seen in reduction of both local and distant failures [14]. Even in the era of concurrent chemotherapy (CC) plus intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), IC appeared to achieve benefit in distant metastasis–free survival (DMFS) [15] and even overall survival (OS) [16]. Therefore, the combination of IC with concurrent chemoradiotherapy is a popular option for cases of locoregionally advanced disease with extensive involvement.

But unfortunately, a small number of patients fail to receive CC after finishing IC in clinical reality. The main reasons include, but are not restricted to, treatment costs, toxicities, and refusal for no reason. Nothing is known about IC followed by IMRT, as it has barely been compared head-to-head with the standard of care. Because more recent randomized trials [17], [18], [19] comparing IMRT plus CC with or without IC indicated no improvement of survival, IC followed by IMRT might be a promising approach with inferior survival outcomes but reduced toxicities. We thus retrospectively analyzed data of 396 patients receiving IC or CC plus IMRT, especially using propensity score matching method to mimic randomized trials [20]. This shall provide valuable effect assessment and pivotal reference for the future randomized controlled trials.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We enrolled 396 NPC patients who received treatment at our center between March 2003 and November 2012. All patients were diagnosed by history and physical examination, hematology and biochemistry profiles, fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy with biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of nasopharynx and neck, chest radiography or computed tomography (CT), abdominal sonography or CT, and technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate whole-body bone scan or CT/MRI of bones, and/or [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and CT. Patients were restaged based on the 2010 International Union Against Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for NPC.

Treatment

All patients were treated by IC or CC plus definitive IMRT. The target volumes of IMRT were defined in accordance with the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements reports 50 and 62. The primary nasopharyngeal gross tumor volume together with enlarged retropharyngeal nodes (GTVnx) and the involved cervical lymph nodes (GTVnd) were determined from the imaging, clinical, and endoscopic findings. Patients in the IC cohort were examined by MRI 2 weeks after the final cycle of chemotherapy to determine GTVnx and GTVnd. The first clinical tumor volume (CTV1) was defined as the GTVnx plus a margin of 5 to 10 mm for potential microscopic spread, including the entire nasopharynx mucosa plus a 5-mm submucosal volume. The second CTV (CTV2) was defined by adding a margin of 5 to 10 mm to CTV1 (when CTV2 was adjacent to critical organs such as brain stem and spinal cord, the margin was reduced to 3 to 5 mm) and included the retropharyngeal lymphnodal regions, clivus, skull base, pterygoid fossae, parapharyngeal space, inferior sphenoid sinus, posterior edge of the nasal cavity and maxillary sinuses, and bilateral cervical lymphatic area. Prescribed radiation doses were 68 Gy or greater to the planning tumor volume (PTV) of GTVnx, 60 to 68 Gy to PTV of GTVnd, 60 Gy or greater to PTV of CTV1, and 50 Gy or greater to PTV of CTV2 in 30 to 33 fractions. Further details of IMRT have been described previously [21]. IC regimen consisted of docetaxel/paclitaxel plus cisplatin/nedaplatin, cisplatin/nedaplatin plus fluorouracil, or docetaxel/paclitaxel plus cisplatin/nedaplatin plus fluorouracil given every 3 weeks for 2 to 3 cycles before radiotherapy. CC regimen consisted of 80 to 100 mg/m2 cisplatin given every 3 weeks for 2 to 3 cycles, or 30 to 40 mg/m2 cisplatin given weekly for up to 7 cycles.

Follow-Up

Patients underwent conventional examination every 3 to 6 months during the first 3 years and every 6 to 12 months thereafter until death to detect possible locoregional relapse or distant metastasis. Actually, the examination during this period was in line with that before treatment. Confirmed locoregional relapse, distant metastasis, or consistent disease received reirradiation, surgery, and/or chemotherapy. Patients without recent examination tests in the medical records were followed up by telephone.

Statistical Analysis

To reduce possible biases to a minimum in this retrospective analysis, we used propensity score matching method [22] to match IC plus IMRT cohort (case) with IMRT plus CC cohort (control). Propensity scores were computed by logistic regression, taking into account age, sex, histology (WHO II, differentiated nonkeratinizing carcinoma; WHO III, undifferentiated nonkeratinizing carcinoma [23]), T stage, N stage, and clinical stage. Propensity-matched cohorts were thus established following matching without replacement at equal ratio on those scores.

Characteristics of patients were compared using t test (continuous variable), χ2 test (categorical variable), and standardized difference [24]. Failure-free survival (FFS, time from treatment to evidence of treatment failure), OS (time from treatment to death from any cause), DMFS (time from treatment to the first distant metastasis), and locoregional relapse–free survival (LRFS, time from treatment to the first locoregional relapse) were estimated with Kaplan-Meier method [25], log-rank test, and Cox proportional hazards model [26]. In the propensity-matched cohort, survival outcomes were estimated using stratified log-rank test by matched pairs and Cox proportional hazards model with a robust variance estimator to account for the clustering within matched pairs [27].

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23.0 and Stata version 12.0. Two-sided P values < .05 and standardized difference > 0.10 [28] were considered to be significant.

Results

Patients

Initially, 94 (23.7%) and 302 (76.3%) patients were treated with IC plus IMRT and IMRT plus CC, respectively. Of note, patients with advanced T stage, N stage, or overall clinical stage tended to receive IC plus IMRT, whereas such characteristics as age and sex scarcely affected treatment options. Following propensity score matching, 94 patients treated with IC plus IMRT and 94 patients treated with IMRT plus CC remained in the propensity-matched cohort. The matched patients in both arms had balanced characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Induction or CC Plus IMRT

| The Original Unmatched Cohort |

The Propensity-Matched Cohort |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC + IMRT (n = 94) |

IMRT + CC (n = 302) |

P | Standardized Difference | IC + IMRT (n = 94) |

IMRT + CC (n = 94) |

P | Standardized Difference | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||

| Age | .872 | 0.018 | .548 | 0.087 | ||||

| Mean | 44.99 | 45.19 | 44.99 | 44.01 | ||||

| SD | 11.59 | 10.34 | 11.59 | 10.69 | ||||

| Median | 44.50 | 45.00 | 44.50 | 43.50 | ||||

| Sex | .904 | 0.014 | .866 | 0.025 | ||||

| Male | 70 (74.5) | 223 (73.8) | 70 (74.5) | 71 (75.5) | ||||

| Female | 24 (25.5) | 79 (26.2) | 24 (25.5) | 23 (24.5) | ||||

| Histology* | .461 | 0.091 | 1.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| II | 4 (4.3) | 19 (6.3) | 4 (4.3) | 4 (4.3) | ||||

| III | 90 (95.7) | 283 (93.7) | 90 (95.7) | 90 (95.7) | ||||

| T stage | .050 | .978 | ||||||

| T1 | 7 (7.4) | 31 (10.3) | 0.099 | 7 (7.4) | 7 (7.4) | 0.000 | ||

| T2 | 15 (16.0) | 59 (19.5) | 0.094 | 15 (16.0) | 13 (13.8) | 0.060 | ||

| T3 | 34 (36.2) | 135 (44.7) | 0.175 | 34 (36.2) | 36 (38.3) | 0.044 | ||

| T4 | 38 (40.4) | 77 (25.5) | 0.322 | 38 (40.4) | 38 (40.4) | 0.000 | ||

| N stage | .124 | .985 | ||||||

| N0 | 14 (14.9) | 43 (14.2) | 0.019 | 14 (14.9) | 13 (13.8) | 0.030 | ||

| N1 | 50 (53.2) | 197 (65.2) | 0.247 | 50 (53.2) | 52 (55.3) | 0.043 | ||

| N2 | 23 (24.5) | 46 (15.2) | 0.233 | 23 (24.5) | 23 (24.5) | 0.000 | ||

| N3 | 7 (7.4) | 16 (5.3) | 0.088 | 7 (7.4) | 6 (6.4) | 0.042 | ||

| Clinical stage | .004 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||||

| II | 10 (10.6) | 69 (22.8) | 0.331 | 10 (10.6) | 10 (10.6) | |||

| III | 40 (42.6) | 140 (46.4) | 0.077 | 40 (42.6) | 40 (42.6) | |||

| IV | 44 (46.8) | 93 (30.8) | 0.333 | 44 (46.8) | 44 (46.8) | |||

Based on the criteria of WHO histological type (1991): II, differentiated nonkeratinizing carcinoma; III, undifferentiated nonkeratinizing carcinoma.

Survival Outcomes

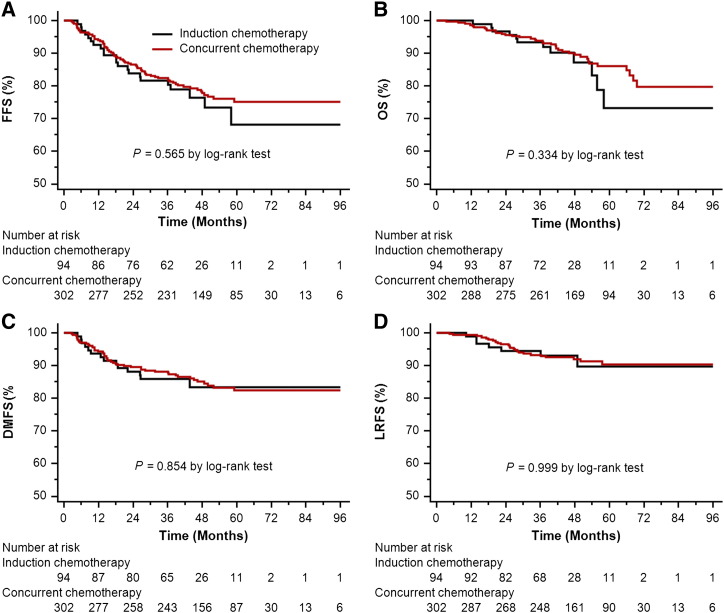

In the original unmatched cohort of 396 patients, median follow-up time was 40.58 months (8.33-99.73 months) for the IC arm and 49.77 months (3.50-107.63 months) for the CC arm, respectively. Overall, 3-year FFS, OS, DMFS, and LRFS rates did not differ significantly between the two arms (FFS 80.3% vs 82.0%, P = .565; OS 93.4% vs 93.8%, P = .334; DMFS 85.9% vs 87.7%, P = .854; and LRFS 93.1% vs 93.3%, P = .999; Figure 1, A–D). Accounting for age (continuous), sex, T stage, and N stage in multivariate analysis, IC plus IMRT was not associated with higher risk of death, locoregional relapse, or distant metastasis than IMRT plus CC (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the IC arm and the CC arm in the original cohort of 396 patients. (A) FFS; (B) OS; (C) DMFS; (D) LRFS.

Table 2.

Summary of Important Prognostic Factors in Multivariate Analysis

| The Original Unmatched Cohort |

The Propensity-Matched Cohort |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P* | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P† | |

| FFS | ||||

| IC + IMRT vs IMRT + CC | 0.99 (0.61-1.61) | .963 | 0.82 (0.44-1.52) | .522 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | .940 | 1.01 (0.98-1.04) | .488 |

| Sex | 0.92 (0.56-1.49) | .730 | 1.04 (0.52-2.06) | .911 |

| Histology | 0.50 (0.23-1.11) | .089 | 1.69 (0.20-14.09) | .628 |

| T stage | 1.65 (1.27-2.14) | < .001 | 1.83 (1.24-2.69) | .002 |

| N stage | 1.49 (1.12-1.98) | .006 | 1.62 (0.94-2.79) | .081 |

| OS | ||||

| IC + IMRT versus IMRT + CC | 0.90 (0.46-1.75) | .746 | 0.86 (0.39-1.89) | .700 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.03 (1.00-1.05) | .064 | 1.03 (0.99-1.07) | .113 |

| Sex | 0.82 (0.42-1.62) | .575 | 0.83 (0.34-1.99) | .671 |

| Histology | 0.58 (0.21-1.64) | .306 | – | – |

| T stage | 2.06 (1.40-3.03) | < .001 | 2.75 (1.59-4.76) | < .001 |

| N stage | 2.00 (1.37-2.90) | < .001 | 2.25 (1.22-4.16) | .009 |

| DMFS | ||||

| IC + IMRT versus IMRT + CC | 1.09 (0.60-2.00) | .776 | 0.85 (0.40-1.82) | .672 |

| Age (continuous) | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .690 | 0.99 (0.96-1.03) | .741 |

| Sex | 0.81 (0.43-1.50) | .499 | 1.16 (0.52-2.60) | .724 |

| Histology | 0.48 (0.19-1.24) | .129 | – | – |

| T stage | 1.67 (1.21-2.31) | .002 | 2.22 (1.38-3.57) | .001 |

| N stage | 1.90 (1.36-2.64) | < .001 | 2.28 (1.21-4.31) | .011 |

| LRFS | ||||

| IC + IMRT versus IMRT + CC | 1.06 (0.45-2.47) | .899 | 0.95 (0.30-3.00) | .936 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | .457 | 0.99 (0.94-1.04) | .684 |

| Sex | 0.99 (0.44-2.22) | .976 | 0.74 (0.19-2.96) | .671 |

| Histology | 0.51 (0.15-1.71) | .276 | 0.49 (0.06-3.67) | .486 |

| T stage | 1.29 (0.86-1.93) | .221 | 1.10 (0.64-1.89) | .727 |

| N stage | 1.31 (0.80-2.12) | .282 | 1.01 (0.37-2.77) | .981 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), sex, histology, T stage, and N stage.

Adjusted for the same covariates with a robust variance estimator to account for the clustering within matched pair.

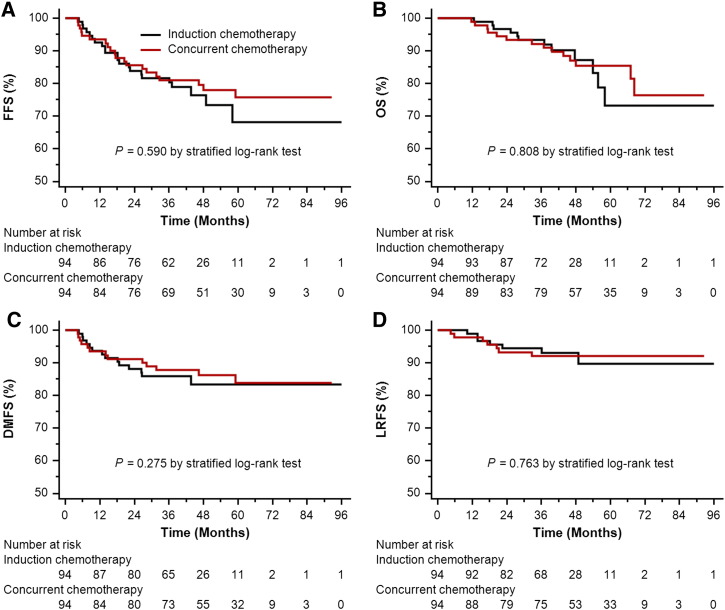

In the propensity-matched cohort of 188 patients, median follow-up time was 40.58 months (8.33-99.73 months) for the IC arm and 53.57 months (4.00-92.60 months) for the CC arm, respectively. In univariate analysis, IC plus IMRT achieved similar survival to IMRT plus CC (3-year FFS 80.3% vs 81.0%, P = .590; OS 93.4% vs 92.1%, P = .808; DMFS 85.9% vs 87.7%, P = .275; and LRFS 93.1% vs 92.0%, P = .763; Figure 2, A–D). In multivariate analysis, IC plus IMRT was also highly comparable to IMRT plus CC in risk of treatment failure, death, locoregional relapse, and distant metastasis (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the IC arm and the CC arm in the propensity-matched cohort of 188 patients. (A) FFS; (B) OS; (C) DMFS; (D) LRFS.

Grade 3 to 4 Hematological Toxicities

In the propensity-matched cohort, IC plus IMRT significantly increased the incidence of grade 3 to 4 neutropenia, whereas IMRT plus CC tended to result in more leucopenia. The rates of grade 3 to 4 anemia and thrombocytopenia were similar in both cohorts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Grade 3 to 4 Hematological Toxicities in the Propensity-Matched Cohort

| IC + IMRT (n = 94) | IMRT + CC (n = 94) | P | Standardized Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leucopenia | 14 (14.89%) | 24 (25.53%) | .069 | 0.267 |

| Neutropenia | 27 (40.91%) | 10 (21.74%) | .034 | 0.467 |

| Anemia | 5 (5.32%) | 6 (6.38%) | .756 | 0.045 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (6.38%) | 11 (11.70%) | .204 | 0.186 |

Discussion

Currently, no strong evidence from phase III randomized trials supports the addition of IC to radiotherapy in locoregionally advanced NPC, whereas CC plus radiotherapy is the standard recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network because of the confirmed survival benefits [29]. Thus, speculatively, IC followed by IMRT appears to be inferior to IMRT plus CC. However, head-to-head comparison of these two approaches in the present study showed no significant differences in survival in both unmatched and matched cohorts. Actually, prior studies had given some hints in favor of this insignificant difference.

A study from Japan [30] investigated IC regimen of cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil plus methotrexate plus leucovorin (PFML) in 21 NPC patients versus CC regimen of PFML or docetaxel plus cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil in 25 patients, and observed no difference in survival. Besides, a study from Taiwan [31] also found similar survival between 38 patients who underwent IC of MEPFL regimen (mitomycin, epirubicin, cisplatin fluorouracil, and leucovorin) or PFL regimen (cisplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin) and 90 patients receiving CC of cisplatin or cisplatin and fluorouracil. Certainly, the small sample size in both studies maybe had insufficient power to detect differences, if they existed. More importantly, a large phase III randomized trial from Shanghai [32] compared IC plus adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) with CC plus AC among 338 stage III to IVb (the 2002 International Union Against Cancer/American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system) patients who received 2 cycles of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil before or during 2DCRT and the same regimen at equal dosage for 4 cycles after radiotherapy. The trial showed similar OS and DFS between IC and CC but more acute toxicities from CC. As IMRT can achieve better LRFS and OS than 2DCRT [33], it is less likely to observe significant differences between IC and CC in the IMRT era. This trial strongly supported the outcomes of our present study despite the differences in chemotherapy regimens and the addition of AC in both arms.

In addition, the outcomes of IMRT plus cisplatin-based CC in our study were not inferior [17], [34] but even superior [16], [19] to those from randomized trials, whereas the results of IC plus IMRT were quite similar to those in randomized trials [16], [17]. So it was not unusual regarding the insignificant survival differences between IC plus IMRT and IMRT plus CC in our study.

The major strength of this study was the head-to-head comparison of IC with CC in NPC patients in the IMRT era using propensity score matching and multivariate analysis. The presented data were derived from a single institution in an endemic area with expertise in diagnosing and treating this disease, which provided the utility in treatment, especially the IMRT technique. The major limitation was that the small number of patients in this study provided relative low power to compare these two treatment approaches. Especially the smaller sample size in the matched cohort may lead to skewed result. But this report was currently the largest-scale head-to-head comparison in contrast with prior publications such as the study by Li et al. [35]. Further investigations with sufficient power are definitely warranted. Data on DNA copy number of the Epstein-Barr virus were missing in most of the cases, and acute nonhematological and late toxicities were unavailable because of the retrospective design and the long time span between the first and the last included case. Owing to the low sensitivity rate of chest radiography compared with chest CT, some patients might be delayed in detecting lung metastasis and had falsely high DMFS rate as a consequence. But the intrinsic differences in DMFS might scarcely change, as the chance of delay was equal in patients in both arms. Another limitation caused by the retrospective design was the heterogeneity of IC regimen and doses. Besides, experienced locoregional relapse or distant metastasis was updated from telephone call for some patients who completed the examination tests out of our cancer center.

In conclusion, this study indicated no significant differences in survival between IC and CC for NPC patients who received IMRT.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

As a retrospective study, individual informed consent was waived given the anonymous analysis of routine data.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin DM. IARC Press; Lyon: 2004. Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:114–119. doi: 10.5732/cjc.010.10377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1765–1777. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri PG, Fu KK, Cooper J, Vuong T, Forastiere AA, Adams G, Sakr WA, Schuller DE. Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1310–1317. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin JC, Jan JS, Hsu CY, Liang WM, Jiang RS, Wang WY. Phase III study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: positive effect on overall and progression-free survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:631–637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong DL, Sham JS, Au GK, Chua DT, Kwong PW, Cheng AC, Wu PM, Law MW, Kwok CC, Yau CC. Concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a factorial study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2643–2653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan AT, Teo PM, Ngan RK, Leung TW, Lau WH, Zee B, Leung SF, Cheung FY, Yeo W, Yiu HH. Concurrent chemotherapy-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: progression-free survival analysis of a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2038–2044. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wee J, Tan EH, Tai BC, Wong HB, Leong SS, Tan T, Chua ET, Yang E, Lee KM, Fong KW. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against cancer stage III and IV nasopharyngeal cancer of the endemic variety. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6730–6738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.16.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee AW, Lau WH, Tung SY, Chua DT, Chappell R, Xu L, Siu L, Sze WM, Leung TW, Sham JS. Preliminary results of a randomized study on therapeutic gain by concurrent chemotherapy for regionally-advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: NPC-9901 Trial by the Hong Kong Nasopharyngeal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6966–6975. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.7542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cvitkovic E, Eschwege F, Rahal M, O SK. Preliminary results of a randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin, epirubicin, bleomycin) plus radiotherapy vs. radiotherapy alone in stage IV (> or = N2, M0) undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a positive effect on progression-free survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;35:463–469. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(96)80007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua DT, Sham JS, Choy D, Lorvidhaya V, Sumitsawan Y, Thongprasert S, Vootiprux V, Cheirsilpa A, Azhar T, Reksodiputro AH. Preliminary report of the Asian-Oceanian Clinical Oncology Association randomized trial comparing cisplatin and epirubicin followed by radiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in the treatment of patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian-Oceanian Clinical Oncology Association Nasopharynx Cancer Study Group. Cancer. 1998;83:2270–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hareyama M, Sakata K, Shirato H, Nishioka T, Nishio M, Suzuki K, Saitoh A, Oouchi A, Fukuda S, Himi T. A prospective, randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:2217–2223. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma J, Mai HQ, Hong MH, Min HQ, Mao ZD, Cui NJ, Lu TX, Mo HY. Results of a prospective randomized trial comparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1350–1357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.5.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chua DT, Ma J, Sham JS, Mai HQ, Choy DT, Hong MH, Lu TX, Min HQ. Long-term survival after cisplatin-based induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a pooled data analysis of two phase III trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1118–1124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang LN, Gao YH, Lan XW, Tang J, OuYang PY, Xie FY. Effect of taxanes-based induction chemotherapy in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a large scale propensity-matched study. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:950–956. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hui EP, Ma BB, Leung SF, King AD, Mo F, Kam MK, Yu BK, Chiu SK, Kwan WH, Ho R. Randomized phase II trial of concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy with or without neoadjuvant docetaxel and cisplatin in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:242–249. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan T, Lim WT, Fong KW, Cheah SL, Soong YL, Ang MK, Ng QS, Tan D, Ong WS, Tan SH. Concurrent chemo-radiation with or without induction gemcitabine, carboplatin, and paclitaxel: a randomized, phase 2/3 trial in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee AW, Ngan RK, Tung SY, Cheng A, Kwong DL, Lu TX, Chan AT, Chan LL, Yiu H, Ng WT. Preliminary results of trial NPC-0501 evaluating the therapeutic gain by changing from concurrent-adjuvant to induction-concurrent chemoradiotherapy, changing from fluorouracil to capecitabine, and changing from conventional to accelerated radiotherapy fractionation in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 2015;121:1328–1338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fountzilas G, Ciuleanu E, Bobos M, Kalogera-Fountzila A, Eleftheraki AG, Karayannopoulou G, Zaramboukas T, Nikolaou A, Markou K, Resiga L. Induction chemotherapy followed by concomitant radiotherapy and weekly cisplatin versus the same concomitant chemoradiotherapy in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a randomized phase II study conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) with biomarker evaluation. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:427–435. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S. A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun X, Su S, Chen C, Han F, Zhao C, Xiao W, Deng X, Huang S, Lin C, Lu T. Long-term outcomes of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for 868 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an analysis of survival and treatment toxicities. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Agostino RB., Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17:2265–2281. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::aid-sim918>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin LH. Histological Typing of Tumors of Upper Respiratory Tract and Ear. In: In Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin LH, editors. International Histological Classification of Tumours. 2nd ed. WHO; Geneva: 1991. pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat Med. 2014;33:1242–1258. doi: 10.1002/sim.5984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–398. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan AT, Leung SF, Ngan RK, Teo PM, Lau WH, Kwan WH, Hui EP, Yiu HY, Yeo W, Cheung FY. Overall survival after concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:536–539. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Komatsu M, Tsukuda M, Matsuda H, Horiuchi C, Taguch T, Takahashi M, Nishimura G, Mori M, Niho T, Ishitoya J. Comparison of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus induction chemotherapy followed by radiation in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:681–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu SY, Wu YH, Yang MW, Hsueh WT, Hsiao JR, Tsai ST, Chang KY, Chang JS, Yen CJ. Comparison of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radiation in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma in endemic area: experience of 128 consecutive cases with 5 year follow-up. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:787–796. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu T, Hu C, Zhu G, He X, Wu Y, Ying H. Preliminary results of a phase III randomized study comparing chemotherapy neoadjuvantly or concurrently with radiotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29:272–278. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang MX, Li J, Shen GP, Zou X, Xu JJ, Jiang R, You R, Hua YJ, Sun Y, Ma J. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy prolongs the survival of patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma compared with conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy: a 10-year experience with a large cohort and long follow-up. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:2587–2595. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen L, Hu CS, Chen XZ, Hu GQ, Cheng ZB, Sun Y, Li WX, Chen YY, Xie FY, Liang SB. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3 multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:163–171. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70320-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li WF, Li YQ, Chen L, Zhang Y, Guo R, Zhang F, Peng H, Sun Y, Ma J. Propensity-matched analysis of three different chemotherapy sequences in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated using intensity-modulated radiotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:810–818. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1768-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]