Abstract

Objectives

An obstetric comorbidity index has been developed recently with superior performance characteristics relative to general comorbidity measures in an obstetric population. This study aimed to externally validate this index and to examine the impact of including hospitalisation/delivery records only when estimating comorbidity prevalence and discriminative performance of the obstetric comorbidity index.

Design

Validation study.

Setting

Alberta, Canada.

Population

Pregnant women who delivered a live or stillborn infant in hospital (n = 5995).

Methods

Administrative databases were linked to create a population‐based cohort. Comorbid conditions were identified from diagnoses for the delivery hospitalisation, all hospitalisations and all healthcare contacts (i.e. hospitalisations, emergency room visits and physician visits) that occurred during pregnancy and 3 months pre‐conception. Logistic regression was used to test the discriminative performance of the comorbidity index.

Main outcome measures

Maternal end‐organ damage and extended length of stay for delivery.

Results

Although prevalence estimates for comorbid conditions were consistently lower in delivery records and hospitalisation data than in data for all healthcare contacts, the discriminative performance of the comorbidity index was constant for maternal end‐organ damage [all healthcare contacts area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) = 0.70; hospitalisation data AUC = 0.67; delivery data AUC = 0.65] and extended length of stay for delivery (all healthcare contacts AUC = 0.60; hospitalisation data AUC = 0.58; delivery data AUC = 0.58).

Conclusions

The obstetric comorbidity index shows similar performance characteristics in an external population and is a valid measure of comorbidity in an obstetric population. Furthermore, the discriminative performance of the comorbidity index was similar for comorbidities ascertained at the time of delivery, in hospitalisation data or through all healthcare contacts.

Keywords: Comorbidity, International Classification of Diseases, pregnancy, prevalence, validation

Introduction

Pregnancy is a time‐limited health state which can co‐occur with a wide variety of other health conditions ranging from mild to severe, and which can impact upon both maternal and fetal health and health resource utilisation.1 Failure to account for maternal comorbidities in pregnancy‐related research can lead to biased effect estimates.2 However, the prevalence of specific conditions is often low; for example, prevalence estimates for pre‐existing hypertension and diabetes in pregnant women are generally <1%, which can lead to analytical problems associated with small sample sizes.1, 2, 3 In non‐obstetric populations, comorbidity indices (particularly the comorbidity indices of Charlson et al.4 and Elixhauser et al.5) are widely used to adjust for comorbidity. Both of these indices account for multiple comorbidities and create a summary score that can be used in a regression model.4, 5 Neither of these indices is appropriate for an obstetric population, as they both focus on conditions that primarily affect an older population and do not include any pregnancy‐specific conditions.

Bateman et al.6 have recently developed an obstetric comorbidity index using data from 854 823 Medicaid participants. This weighted index combines 20 conditions diagnosed or documented 6 months pre‐conceptionally or during pregnancy in inpatient or outpatient claims data.6 Overall, this index [area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) = 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.65–0.67] outperformed both the Charlson (AUC = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.57–0.59) and Elixhauser (AUC = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.58–0.60) comorbidity scores in its ability to predict maternal end‐organ damage at delivery or within 30 days post‐partum.6 The development of this index represents an important step forwards for pregnancy‐related research; however, its generalisability is unknown. Furthermore, its reliance on outpatient diagnoses and diagnoses prior to pregnancy may limit its use in other studies, as many population‐based pregnancy studies are restricted to hospitalisation data or delivery records.

This study aimed to assess the construct validity of the ‘Comorbidity Index for Use in Obstetric Patients’ developed by Bateman et al.6 in an external population, update the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)‐9 codes used by Bateman et al. to ICD‐10 codes to enhance its generalisability to countries other than the USA, and to examine the impact of including only (a) hospitalisation records and (b) delivery records on the prevalence of comorbidities and the performance of Bateman's comorbidity index.

Materials and methods

The population‐based study cohort consisted of all women who delivered a live or stillborn infant in a hospital in the Calgary Zone of Alberta Health Services and conceived between 4 November 2007 and 23 February 2008 (n = 5995). Full details of data linkage can be found elsewhere,7 but briefly this dataset was created by linked records from 12 unique clinical and administrative databases, and contains data on all healthcare contacts that occurred 3 months prior to conception, during pregnancy and 3 months post‐partum. Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary.

Comorbid conditions included in the Bateman comorbidity index were defined using the ICD‐9‐CM (Clinical Modification) codes specified in Bateman's original article in the physician claims data and were converted to ICD‐10‐CA (Canadian Modification) codes for use in the hospitalisation and emergency room data (Appendix S1, see Supporting Information). Comorbidity scores were derived by searching all coding positions (up to 25, 10 and three diagnostic codes, respectively, are allowed in hospitalisation, emergency room and physician billing data) for an ICD code of interest to determine whether a particular comorbidity was present, multiplying by the weights derived by Bateman et al. (see Table 1) and summing to create a summary score. Two outcome measures were assessed – maternal end‐organ damage and extended length of stay for delivery. Maternal end‐organ damage was defined according to Bateman et al. (Appendix S2, see Supporting Information), and an extended length of stay for delivery was defined as a length of stay ≥3 days following a vaginal delivery or ≥5 days following a caesarean delivery. Initially, all healthcare contacts (inpatient data, emergency room visits and outpatient physician claims) occurring pre‐conceptionally and during pregnancy were searched for diagnosis codes for comorbid conditions and all healthcare contacts from the time of delivery to 3 months post‐partum were searched for diagnosis codes related to maternal end‐organ damage. This search was then restricted to inpatient hospitalisation data only and, finally, to delivery records only. Comorbidities, maternal end‐organ injury and length of stay were identified at the time of delivery if they appeared in any of the 25 diagnostic fields of a hospitalisation that also contained a Z37.x ICD‐10‐CA code.

Table 1.

Prevalence (%) of comorbidities by reporting source

| Comorbidity | Weight in obstetric comorbidity index | Prevalence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery n (%, 95% CI) | Hospitalisation data n (%, 95% CI) | All healthcare contacts n (%, 95% CI) | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 1 | <5 | <5 | 16 (0.3, 0.1–0.4) |

| Asthma | 1 | 10 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) | 11 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) | 186 (3.1, 2.7–3.5) |

| Cardiac valvular disease | 2 | 5 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 5 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 11 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) |

| Chronic congestive heart failure | 5 | 0 | 0 | <5 |

| Chronic ischaemic heart disease | 3 | <5 | <5 | 10 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) |

| Chronic renal disease | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 (0.3, 0.1–0.4) |

| Congenital heart disease | 4 | 16 (0.3, 0.1–0.4) | 17 (0.3, 0.1–0.4) | 88 (1.5, 1.2–1.8) |

| Drug abuse | 2 | 11 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) | 13 (0.2, 0.1–0.3) | 30 (0.5, 0.3–0.7) |

| Gestational hypertension | 1 | 343 (5.7, 5.1–6.3) | 354 (5.9, 5.3–6.5) | 246 (4.1, 3.6–4.6) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 2 | <5 | <5 | <5 |

| Mild/unspecified pre‐eclampsia | 2 | 7 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 8 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 140 (2.3, 20.0–2.7) |

| Multiple gestation | 2 | 122 (2.0, 1.7–2.4) | 122 (2.0, 1.7–2.4) | 145 (2.4, 2.0–2.8) |

| Placenta praevia | 2 | 40 (0.7, 0.5–0.8) | 47 (0.8, 0.6–1.0) | 92 (1.5, 1.2–1.8) |

| Pre‐existing diabetes mellitus | 1 | 37 (0.6, 0.4–0.8) | 37 (0.6, 0.4–0.8) | 343 (5.7, 5.1–6.3) |

| Pre‐existing hypertension | 1 | 25 (0.4, 0.3–0.6) | 26 (0.4, 0.3–0.6) | 196 (3.3, 2.8–3.7) |

| Previous caesarean delivery | 1 | 683 (11.4, 10.6–12.2) | 683 (11.4, 10.6–12.2) | 800 (13.3, 12.5–14.2) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe pre‐eclampsia | 5 | 77 (1.3, 1.0–1.6) | 79 (1.3, 1.0–1.6) | 156 (2.6, 2.2–3.0) |

| Sickle cell disease | 3 | 7 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 7 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) | 14 (0.2, 0.1–0.4) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 2 | <5 | <5 | 5 (0.1, 0.0–0.2) |

| Maternal age at delivery (years) | ||||

| >44 | 3 | 155 (2.6, 2.2–3.0) | ||

| 40–44 | 2 | 216 (3.6, 3.1–4.1) | ||

| 35–39 | 1 | 1146 (19.1, 18.1–20.1) | ||

CI, confidence interval.

The prevalence of individual comorbidities and the overall comorbidity score were assessed by reporting source (all healthcare contacts, hospitalisation records only and delivery records only). The kappa statistic was used to examine the agreement between data sources for comorbidities that affected at least five women. The discrimination of the comorbidity index was assessed in each reporting source by constructing logistic regression models predicting either maternal end‐organ damage or extended length of stay for delivery using the continuous comorbidity score as the exposure variable and measuring AUC. The stratification capacity (proportion of women categorised as low and high risk) was assessed by examining the proportion of women allocated to each score, and calibration accuracy (correlation between predicted and observed outcomes) was assessed by examining the Brier score (the sum of the average squared error difference between the forecasted and observed outcome, with ‘0’ representing perfect forecasting) and what proportion of women in each comorbidity category experienced end‐organ damage or an extended length of stay for delivery. Finally, odds ratios and 95% CIs (derived from logistic regression) were used to illustrate the association between the comorbidity index and each outcome of interest. All analyses were conducted using Stata 12 SE (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

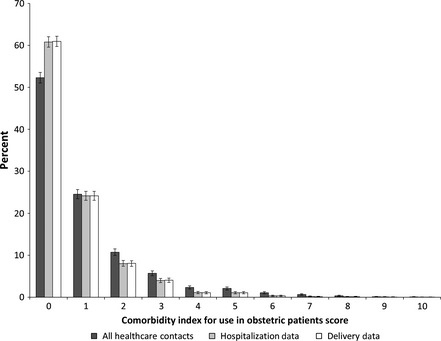

The prevalence of specific comorbidities (Table 1) and the overall comorbidity score (Figure 1) varied by reporting source. Prevalence estimates for comorbid conditions in hospitalisation data and delivery data only were generally similar, as few women (7.4%) were hospitalised during the pre‐conception or prenatal periods for reasons other than delivery. Consistently higher prevalence estimates for comorbidities were observed when examining diagnoses found in all healthcare contacts; this difference was often statistically significant and clinically meaningful. For example, the prevalence of asthma increased from 0.2% as found in delivery and hospitalisation data to 3.1% when all healthcare contacts were examined, and the prevalence of maternal congenital heart disease increased from 0.3 to 1.5%. A notable exception to this trend was for conditions that could occur outside of pregnancy (i.e. chronic hypertension), but also have a pregnancy‐specific disease state (i.e. gestational hypertension, pre‐eclampsia). Higher rates of the disease‐specific state were observed in delivery records and hospitalisation data than in data from all healthcare contacts, whereas higher rates of the chronic pre‐existing condition were found in data from all healthcare contacts, meaning that the absolute number of cases and the prevalence rates of gestational hypertension were artificially inflated at the time of delivery, and the absolute number of cases and the prevalence rates of chronic hypertension were systematically under‐ascertained. This trend was observed for both hypertensive disorders and diabetes (data on gestational diabetes are not shown as it is not a part of the comorbidity index, but are available on request).

Figure 1.

Distribution of comorbidity scores by reporting source (n = 5995).

Agreement of individual comorbidities varied between datasets and type of comorbidity (Table 2). The agreement between hospitalisation data and delivery hospitalisation data was excellent (κ ≥ 0.90) for all comorbidities. The only comorbidity with adequate agreement (κ ≥ 0.70) between all reporting sources was multiple gestation. Agreement between reporting sources was generally poor (κ ≤ 0.50) for all other comorbidities.

Table 2.

Agreement in comorbidity diagnoses between reporting sources (n ≥ 5)

| Comorbidity | κ (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delivery and hospitalisation data | Delivery and emergency room data | Delivery and physician claims data | Hospitalisation and emergency room data | Hospitalisation and physician claims data | Emergency room and physician claims data | |

| Asthma | 0.95 (0.86–1.00) | 0.03 (0.00–0.10) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) | 0.03 (0.00–0.10) | 0.02 (0.00–0.05) | 0.31 (0.23–0.39) |

| Cardiac valvular disease | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.46 (0.13–0.80) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.46 (0.13–0.80) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| Congenital heart disease | 0.97 (0.91–1.00) | 0.07 (0.00–0.15) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.10 (0.01–0.19) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.10 (0.01–0.19) |

| Drug abuse | 0.92 (0.80–1.00) | 0.11 (0.00–0.31) | 0.21 (0.01–0.40) | 0.20 (0.00–0.43) | 0.26 (0.05–0.46) | 0.16 (0.00–0.35) |

| Gestational hypertension | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.56 (0.54–0.62) | 0.10 (0.06–0.15) | 0.60 (0.55–0.64) | 0.13 (0.08–0.17) | 0.16 (0.11–0.20) |

| Mild/unspecified pre‐eclampsia | 0.93 (0.80–1.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 0.03 (0.00–0.06) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 0.04 (0.01–0.07) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) |

| Multiple gestation | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.79 (0.73–0.85) | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) |

| Placenta praevia | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.33 (0.20–0.45) | 0.40 (0.25–0.54) | 0.34 (0.22–0.46) | 0.46 (0.33–0.60) | 0.34 (0.21–0.47) |

| Pre‐existing diabetes mellitus | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.60 (0.49–0.71) | 0.18 (0.13–0.23) | 0.60 (0.49–0.71) | 0.18 (0.13–0.23) | 0.29 (0.24–0.35) |

| Pre‐existing hypertension | 0.98 (0.94–1.00) | 0.31 (0.18–0.45) | 0.18 (0.11–0.26) | 0.31 (0.17–0.44) | 0.19 (0.11–0.26) | 0.15 (0.09–0.22) |

| Previous caesarean delivery | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.20 (0.16–0.24) | 0.40 (0.36–0.44) | 0.20 (0.16–0.24) | 0.40 (0.36–0.44) | 0.11 (0.07–0.16) |

| Severe pre‐eclampsia | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | 0.27 (0.18–0.36) | 0.23 (0.11–0.34) | 0.28 (0.19–0.37) | 0.22 (0.11–0.33) | 0.12 (0.04–0.20) |

| Sickle cell disease | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.22 (0.00–0.58) | 0.27 (0.00–0.56) | 0.22 (0.00–0.58) | 0.27 (0.00–0.56) | 0.20 (0.00–0.53) |

CI, confidence interval.

When examining all healthcare contacts, maternal end‐organ damage occurred in 1.7% of pregnancies. This rate was reduced to 0.8% when limited to hospitalisation data and to 0.7% when limited to delivery data. Regardless of differences in the observed prevalence of comorbidities between reporting sources, the discrimination ability of the comorbidity index of Bateman et al. was remarkably similar between sources for maternal end‐organ damage [all healthcare contacts AUC = 0.65 (95% CI = 0.59–0.71); hospitalisation data AUC = 0.67 (95% CI = 0.58–0.76); delivery data AUC = 0.70 (95% CI = 0.60–0.80)] (Table 3), and in line with that observed in the original population (AUC = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.65–0.67).6 Model stratification was adequate, particularly for women with high scores (i.e. score ≥ 7); however, the vast majority of women had a score of <2 with little to no observed differences in outcomes between women with scores of 0 or scores of 1–2. Model calibration was near perfect, with Brier scores of 0.01 for the models based on delivery and hospitalisation data, and 0.02 for the model derived from all healthcare contacts. A clear dose–response relationship was observed, with a stronger association between maternal end‐organ damage and higher scores; however, the precision of effect estimates for high scores was reduced because of low numbers.

Table 3.

Validation of comorbidity index by reporting source

| Reporting source | Bateman score | Stratification capacity n (%) | Outcome: maternal end‐organ damage | Outcome: extended length of stay for delivery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association | Discrimination ability | Calibration accuracy | Association | Discrimination ability | Calibration accuracy | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Proportion experiencing outcome (%, 95% CI) | Brier score | OR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | Proportion experiencing outcome (%, 95% CI) | Brier score | |||

| Delivery hospitalisations | 0 | 3655 (61.0) | Ref | 0.70 (0.60–0.80) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.01 | Ref | 0.58 (0.56–0.60) | 10.2 (9.2–11.2) | 0.10 |

| 1–2 | 1929 (32.2) | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 1.2 (1.04–1.5) | 12.3 (10.8–13.8) | |||||

| 3–4 | 306 (5.1) | 4.4 (2.5–7.9) | 3.3 (1.3–5.3) | 2.6 (2.0–3.5) | 22.9 (18.2–27.6) | |||||

| 5–6 | 84 (1.4) | 5.1 (2.0–13.1) | 4.8 (0.2–9.3) | 10.2 (6.5–15.8) | 53.6 (42.8–64.3) | |||||

| 7–8 | 16 (0.3) | 18.5 (5.1–67.2) | 18.8 (0.0–38.5) | 2.9 (0.9–9.1) | 25.0 (3.1–46.9) | |||||

| 9–10 | 5 (0.1) | 53.5 (8.7–327.8) | 20.0 (0.0–59.2) | 13.2 (2.2–79.2) | 60.0 (12.0–100.0) | |||||

| Hospitalisation data | 0 | 3646 (60.8) | Ref | 0.67 (0.58–0.76) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.01 | Ref | 0.58 (0.56–0.60) | 10.2 (9.2–11.2) | 0.10 |

| 1–2 | 1933 (32.2) | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 0.5 (0.2–0.8) | 1.2 (1.02–1.4) | 12.2 (10.7–13.6) | |||||

| 3–4 | 305 (5.1) | 4.4 (2.5–7.9) | 3.3 (1.3–5.3) | 2.7 (2.0–3.6) | 23.3 (18.5–28.0) | |||||

| 5–6 | 86 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4–11.1) | 3.5 (0.0–7.4) | 9.7 (6.2–14.9) | 52.3 (41.7–62.9) | |||||

| 7–8 | 18 (0.3) | 22.8 (7.2–72.2) | 22.2 (2.5–42.0) | 4.4 (1.6–11.8) | 33.3 (10.9–55.7) | |||||

| 9–10 | 7 (0.1) | 32.0 (6.0–169.4) | 14.3 (0.0–42.3) | 6.6 (1.5–29.6) | 42.9 (3.3–82.5) | |||||

| All healthcare contacts | 0 | 3135 (52.3) | Ref | 0.65 (0.59–0.71) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 0.02 | Ref | 0.60 (0.58–0.62) | 9.6 (8.6–10.6) | 0.10 |

| 1–2 | 2117 (35.3) | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.2 (1.03–1.46) | 11.5 (10.1–12.8) | |||||

| 3–4 | 481 (8.0) | 3.9 (2.3–6.8) | 4.4 (2.5–6.2) | 2.5 (1.9–3.2) | 20.8 (17.2–24.4) | |||||

| 5–6 | 191 (3.2) | 4.8 (2.3–9.7) | 5.2 (2.1–8.4) | 5.1 (3.7–7.0) | 35.1 (28.3–41.9) | |||||

| 7–8 | 59 (1.0) | 6.3 (2.2–18.2) | 6.7 (0.3–13.3) | 3.8 (2.1–6.8) | 28.8 (17.2–40.5) | |||||

| 9–10 | 12 (0.2) | 28.7 (7.5–110.4) | 25.0 (0.0–50.6) | 4.7 (1.4–15.7) | 33.3 (5.5–61.2) | |||||

AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Extended length of stay for delivery was a more common outcome and occurred in 12.2% of pregnancies. However, similar results were observed in terms of model discrimination and calibration (Table 3). The AUCs were virtually identical between reporting sources [all healthcare contacts AUC = 0.60 (95% CI = 0.58–0.62); hospitalisation data AUC = 0.58 (95% CI = 0.56–0.60); delivery data AUC = 0.58 (95% CI = 0.56–0.60)], and a Brier score of 0.10 was obtained for all models. Although a general dose–response relationship was observed, few differences were seen between women with higher scores on the comorbidity index, potentially indicating that length of stay for delivery is influenced by factors other than health status alone. The model limited to comorbidities recorded during the delivery hospitalisation appears to have the best calibration properties and can better separate women into different risk groups, compared with the model that identifies comorbidities from all healthcare contacts.

Discussion

Main findings

The ‘Comorbidity Index for Use in Obstetric Patients’ developed by Bateman et al.6 has similar performance characteristics in an external population and can be considered as a valid measure of comorbidity in an obstetric population. Furthermore, similar measures of validity were observed regardless of whether comorbidity data were captured only at the time of delivery, only in hospitalisation data or in all healthcare contacts. Although the association between the Bateman comorbidity index and maternal end‐organ damage/extended length of stay for delivery is strong, the predictive ability of this comorbidity index is modest. However, comorbidity indices are not designed to be used in isolation; typically, they represent one variable in regression equations. The results of this study support Bateman's et al.'s conclusion that it is preferable to use this comorbidity score in health services/epidemiological studies relative to other comorbidity indices (i.e. the Charlson and Elixhauser indices) which have not been validated in an obstetric population. The usefulness of this index in clinical practice still needs to be assessed.

Furthermore, a substantial proportion of comorbidities are not documented on the delivery record or in hospitalisation data. The rate of under‐ascertainment varied by condition studied. Multiple studies have reported similar findings,8, 9, 10, 11 leading us to conclude that prevalence estimates based exclusively on the delivery record or hospitalisation data may systematically under‐estimate the frequency of comorbid disease in a pregnant population. This is particularly relevant when studying conditions that can also occur outside of pregnancy, as we found that delivery records over‐coded gestational forms of disease (i.e. gestational hypertension), whilst under‐ascertaining pre‐existing conditions (i.e. chronic hypertension).

Strengths and limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its sole reliance on administrative data. Administrative data are not collected for research purposes and, as such, contain no information on the severity of the condition or many relevant covariates. Furthermore, no ICD code exists to indicate pregnancy, and many comorbidities are coded using general codes (i.e. I10.0 for benign hypertension) instead of pregnancy‐specific codes (i.e. O10.0 for pre‐existing essential hypertension complicating pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium).1 Only a single ICD code for a comorbidity was required to indicate the presence of a comorbid condition, and validation of comorbidity diagnoses with the medical record was outside the scope and budget of this study. However, although this undoubtedly has an impact on the estimated prevalence of conditions, based on the results comparing the performance of the comorbidity index with data obtained at the time of delivery relative to data obtained during pregnancy and 3 months pre‐conceptionally, this does not appear to have an impact on the overall predictive ability of the comorbidity index.

The prevalence of some conditions documented at the time of delivery is unrealistically low and probably reflects both the coding practice, which requires that only conditions that have a direct impact on patient care be coded,11, 12, 13, 14 and under‐coding of conditions. Unfortunately, a chart review to determine the underlying validity of the administrative data codes was not possible given the resources available for this project. In addition, the prevalence of some conditions is influenced by the case definition used. All comorbid conditions in this study were defined as per the original publication using this index6; however, some of the case definitions differed from those used in other comorbidity indices4, 5 (beyond that expected by simply including codes related to obstetric forms of disease or codes from the ‘O’ chapter of ICD‐10 or in the 630–679 range of ICD‐9). For example, alcohol abuse has a much broader definition in the indices of both Charlson et al.4 (ICD‐9: 265.2, 291.1–291.3, 291.5, 291.8, 291.9, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0, 357.5, 425.5, 535.3, 571.0–571.3, 980.x, V11.3; ICD‐10: F10.x, E52.x, G62.1, I42.6, K29.2, K70.0, K70.3, K70.9, T51.x, Z50.2, Z71.4, Z72.1) and Elixhauser et al.5 (ICD‐9: 265.2, 291.1–291.3, 291.5, 291.8, 291.9, 303.0, 303.9, 305.0, 357.5, 425.5, 535.3, 571.0–571.3, 980.x, V11.3; ICD‐10: F10.x, E52.x, G62.1, I42.6, K29.2, K70.0, K70.3, K70.9, T51.x, Z50.2, Z71.4, Z72.1) than in the Bateman Obstetric Comorbidity Index6 (ICD‐9: 291, 303, 305.0; ICD‐10: F10). The usefulness of this tool is contingent on having valid administrative data that are reflective of clinical practice and diagnoses.

Interpretation

Other authors have also reported preferential reporting of gestational forms of disease relative to chronic conditions. For example, a multi‐site US study found that anywhere from 17 to 50% of pregnancies with a code for gestational diabetes also had a code for Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes documented during the 6 months prior to conception.15 As the rate of antenatal hospitalisations continues to decrease in favour of outpatient management,1, 16 hospitalisation and delivery data alone will become increasingly unreliable sources for the assessment of the true prevalence of comorbidities in an obstetric population. An Australian study found that increasing the look‐back period in hospitalisation data can increase the reported prevalence of comorbidities in an obstetric population, with an optimal ascertainment period of 2–3 years prior to delivery.17

Administrative hospitalisation data have been shown to accurately capture intrapartum events and diagnoses in multiple countries12, 18; however, the validity of comorbidity coding in an obstetric population varies by type of comorbidity and source.13, 14, 18, 19 A validation study from Washington State reported that the sensitivity of chronic hypertension in pregnant patients in hospitalisation data was 45.6%,19 whereas Canadian and Australian studies report sensitivities of 83.3 and 85.7%, respectively.14, 18. Other conditions have consistently low sensitivity (i.e. the sensitivity of ICD codes for asthma in an obstetric population were 42.0% in California13 and 12.3% in Washington State19), whereas some conditions consistently have a high sensitivity (i.e. the sensitivity of ICD codes for placenta praevia was 88.0% in California13 and 87.5% in Australia14). It is not believed that these differences in sensitivity are a result of different coding frameworks (i.e. ICD‐9 versus ICD‐10), as a study examining comorbidity coding in the general population using both ICD‐9 and ICD‐10 found that prevalence estimates were generally stable regardless of coding source.20 All validation studies reported high specificities (i.e. >90%) for all comorbidities.13, 14, 18, 19 Hospital coders are only allowed to code conditions that are clearly diagnosed by the care provider and have an impact on patient care, in that they require additional clinical evaluation, treatment, testing or result in a longer length of stay.11, 12, 13, 14 Thus, is it more likely that a comorbid condition would not be coded, than that it would be coded in error.

Conclusion

The ‘Comorbidity Index for Use in Obstetric Patients’ developed by Bateman et al.6 is a valid measure. The use of a single validated comorbidity measure will enhance the comparability of international studies,21 and is encouraged for further pregnancy‐related research.

Disclosure of interests

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to declare.

Contribution to authorship

All authors made a substantial contribution to this work. AM, FB, J‐AJ, AWL, GC and SCT designed the study. AM conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. AM, LML, FB, J‐AJ, AWL, GC and ST participated in the interpretation of the findings, provided critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Details of ethics approval

This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (E‐22576).

Funding

This work was supported by a catalyst grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a research award from Calgary Laboratory Services. At the time of this study, AM was supported by a Fellowship award and a team grant on severe maternal morbidity (MAH–115445) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. ST was supported by a Senior Scholar award from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions. The funders did not have any role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, manuscript preparation and/or publication decision.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes for comorbidities.

Appendix S2. International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes for maternal end‐organ damage.

Acknowledgements

This work has been presented previously at the International Health Data Linkage Network Meeting held in Vancouver, BC, Canada in April 2013. This study is based in part on data provided by Alberta Health. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Alberta. Neither the Government nor Alberta Health expresses any opinion in relation to this study.

Metcalfe A, Lix LM, Johnson J‐A, Currie G, Lyon AW, Bernier F, Tough SC. Validation of an obstetric comorbidity index in an external population. BJOG 2015;122:1748–1755.

Linked article This article is commented on by BT Bateman and JJ Gagne. p. 1756 in this issue. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13297.

References

- 1. Bennett TA, Kotelchuck M, Cox CE, Tucker MJ, Nadeau DA. Pregnancy‐associated hospitalizations in the United States in 1991 and 1992: a comprehensive view of maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:346–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aron DC, Harper DL, Shepardson LB, Rosenthal GE. Impact of risk‐adjusting cesarean delivery rates when reporting hospital performance. J Am Med Assoc 1998;279:1968–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Maternal–fetal conditions necessitating a medical intervention resulting in preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Hernandez‐Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Fischer MA, Creanga AA, et al. Development of a comorbidity index for use in obstetric patients. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:957–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Metcalfe A, Lyon AW, Johnson JA, Bernier F, Currie G, Lix LM, et al. Improving completeness of ascertainment and quality of information for pregnancies through linkage of administrative and clinical data records. Ann Epidemiol 2013;23:444–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lydon‐Rochelle MT, Holt VL, Cardenas V, Nelson JC, Easterling TR, Gardella C, et al. The reporting of pre‐existing maternal medical conditions and complications of pregnancy on birth certificates and in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;193:125–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruce FC, Berg CJ, Joski PJ, Roblin DW, Callaghan WM, Bulkley JE, et al. Extent of maternal morbidity in a managed care population in Georgia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:497–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baldwin LM, Klabunde CN, Green P, Barlow W, Wright G. In search of the perfect comorbidity measure for use with administrative claims data: does it exist? Med Care 2006;44:745–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarfati D, Hill S, Purdie G, Dennett E, Blakely T. How well does routine hospitalisation data capture information on comorbidity in New Zealand? N Z Med J 2010;123:50–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romano PS, Yasmeen S, Schembri ME, Keyzer JM, Gilbert WM. Coding of perineal lacerations and other complications of obstetric care in hospital discharge data. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:717–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Schembri ME, Keyzer JM, Gilbert WM. Accuracy of obstetric diagnoses and procedures in hospital discharge data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;194:992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor LK, Travis S, Pym M, Olive E, Henderson‐Smart DJ. How useful are hospital morbidity data for monitoring conditions occurring in the perinatal period? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005;45:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Andrade SE, Moore Simas TA, Boudreau D, Raebel MA, Toh S, Syat B, et al. Validation of algorithms to ascertain clinical conditions and medical procedures used during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:1168–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bacak SJ, Callaghan WM, Dietz PM, Crouse C. Pregnancy‐associated hospitalizations in the United States, 1999–2000. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192:592–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen JS, Roberts CL, Simpson JM, Ford JB. Use of hospitalisation history (lookback) to determine prevalence of chronic diseases: impact on modelling of risk factors for haemorrhage in pregnancy. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joseph KS, Fahey J. Validation of perinatal data in the Discharge Abstract Database of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Chronic Dis Can 2009;29:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hadfield RM, Lain SJ, Cameron CA, Bell JC, Morris JM, Roberts CL. The prevalence of maternal medical conditions during pregnancy and a validation of their reporting in hospital discharge data. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li B, Evans D, Faris P, Dean S, Quan H. Risk adjustment performance of Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidities in ICD‐9 and ICD‐10 administrative databases. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nadathur SG. Comorbidity indexes from administrative datasets: what is measured? Aust Health Rev 2011;35:507–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes for comorbidities.

Appendix S2. International Classification of Diseases diagnosis codes for maternal end‐organ damage.