Abstract

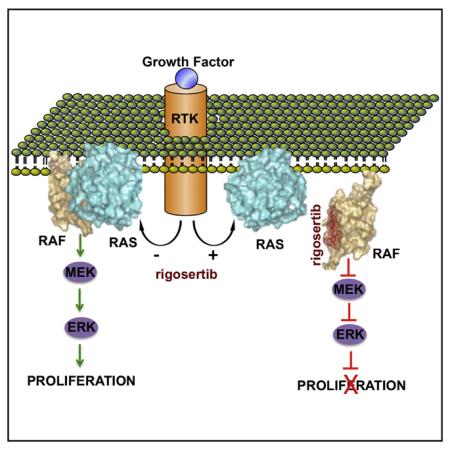

Oncogenic activation of RAS genes via point mutations occurs in 20%–30% of human cancers. The development of effective RAS inhibitors has been challenging, necessitating new approaches to inhibit this oncogenic protein. Functional studies have shown that the switch region of RAS interacts with a large number of effector proteins containing a common RAS-binding domain (RBD). Because RBD-mediated interactions are essential for RAS signaling, blocking RBD association with small molecules constitutes an attractive therapeutic approach. Here, we present evidence that rigosertib, a styryl-benzyl sulfone, acts as a RAS-mimetic and interacts with the RBDs of RAF kinases, resulting in their inability to bind to RAS, disruption of RAF activation, and inhibition of the RAS-RAF-MEK pathway. We also find that rigosertib binds to the RBDs of Ral-GDS and PI3Ks. These results suggest that targeting of RBDs across multiple signaling pathways by rigosertib may represent an effective strategy for inactivation of RAS signaling.

Graphical abstract

In Brief

Binding of a small molecule to the conserved RAS-binding domain of RAF prevents its functional association with RAS and impairs tumorigenic proliferation.

INTRODUCTION

The discovery that oncogenic activation of RAS genes occurs via point mutations (Reddy, 1983; Reddy et al., 1982; Shimizu et al., 1983; Tabin et al., 1982; Taparowsky et al., 1983; Yuasa et al., 1983) and that these mutations occur in 20%–30% of human cancers, (Prior et al., 2012), spearheaded investigations aimed at understanding the biochemical mechanisms that govern the function of these oncoproteins. These studies have shown that oncogenic RAS not only activates proliferative signals but also mediates signals responsible for survival, metastasis, and evasion of apoptosis (Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2011) through interaction with a universe of effector proteins by a highly conserved mechanism (Vojtek and Der, 1998) involving the switch I and switch II regions of RAS and the RAS-binding domains (RBDs) of its effector proteins. It is now estimated that over 100 mammalian proteins, including three key RAS effectors, RAF proteins, RalGDS, and the family of PI3 kinases, share this binding motif (Block et al., 1996; Nassar et al., 1995; Pacold et al., 2000). Studies with RAF suggest that the 78 amino acid N-terminal RBD plays a critical role in its association with the switch I region of RAS at amino acids 32–40 (Block et al., 1996; Nassar et al., 1995; Terada et al., 1999). Interestingly, the RBDs of RAF kinases, PI3Ks, and RalGDS adopt similar, ubiquitin-like fold tertiary structures whereby the molecular interactions with RAS are mediated by side-by-side alignment of β sheets that are stabilized by multiple polar and hydrophobic interactions (Block et al., 1996; Nassar et al., 1995; Terada et al., 1999).

When knockin mice that harbor point mutations in the RBD of P110α (that abolished its interaction with RAS) were crossed with K-RAS LA2 mice that harbor an activating mutation in the K-Ras gene, an impressive 95% reduction in lung tumor formation was observed, suggesting that targeting RAS-RBD interactions might constitute an excellent strategy to inhibit oncogenic RAS signaling (Castellano and Downward, 2011; Gupta et al., 2007).

The development of RAS inhibitors has been challenging due to the lack of well-defined druggable pockets and cavities on the RAS surface. This obstacle could be partly overcome with G12C mutant RAS, which creates a pocket that could be exploited to synthesize a covalent inhibitor specific to RASG12C (Ostrem et al., 2013). While this approach constitutes an important breakthrough, it is necessary to develop a broader approach that enables inhibition of all forms of mutant RAS.

Here, we describe the first identification of a small molecule inhibitor of RAS-RBD protein:protein interaction, rigosertib. Rigosertib, which is in phase III clinical trials for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), is a novel benzyl styryl sulfone (Figure S1A) that inhibits the growth of a wide variety of human tumor cells in vitro and impairs tumor growth in vivo with minimal toxicity (Agoni et al., 2014; Reddy et al., 2011). Because rigosertib is a non-ATP competitive inhibitor, its mechanism of action has not been precisely defined. To identify direct targets of rigosertib, we employed a chemical pulldown method that has been successfully used to identify targets of other drugs such as lenalidomide (Ito et al., 2014). Our results show that rigosertib acts as a RAS-mimetic that binds to the RBDs of the RAS effectors and interferes with their ability to bind to RAS, resulting in a block to activation of RAF kinase activity and inhibition of RAS-RAF-MEK signaling. Our studies also show that rigosertib inhibits the phosphorylation of c-RAF at Ser338, which is required for the activation of its kinase activity (Diaz et al., 1997) and its association with PLK1 (Mielgo et al., 2011).

RESULTS

Rigosertib Binds to RBD Domains of the RAF Family of Proteins

We engineered a biologically active rigosertib-biotin conjugate (Figure S1A) and used this compound as an affinity matrix to identify proteins that bind to rigosertib (RGS) (Figure S1B. Mass spectrometry identified six proteins as principal RGS-binding partners: A-RAF, B-RAF, and c-RAF, Hsp27, Hsp73, and FUBP3 (Figure S1C). In these assays, a biotin-conjugate of a biologically inactive isomer of RGS, ON01911, as well as free RGS or biotin, did not bring down these proteins (Figure S1D). Unlinked RGS competed with the RGS-biotin conjugate, suggesting that they are bona fide targets of RGS (Figure S1E).

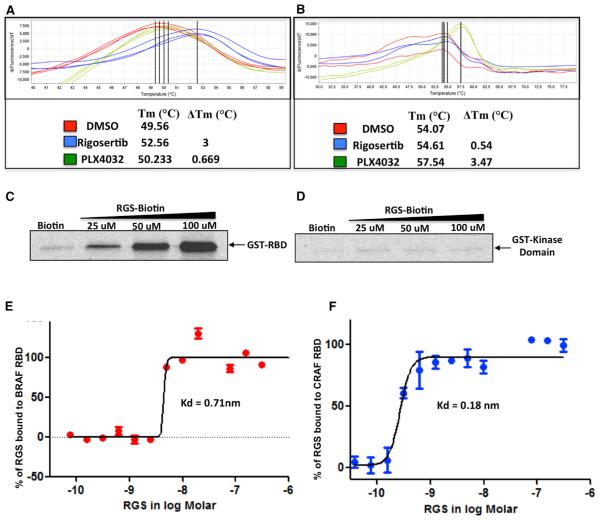

To determine the site to which RGS binds, we subjected recombinant proteins derived from different regions of c-RAF to differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) (Niesen et al., 2007) in the presence of RGS. While the c-RAF kinase domain (KD) did not interact with RGS, the RBD bound to RGS as indicated by the change in Tm (Figures 1A and 1B). In contrast, PLX4032 (vemurafenib), an ATP-competitive RAF inhibitor (Tsai et al., 2008), readily induced a strong thermal shift with the KD but not with the RBD (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Rigosertib Binds to the RBDs of c-RAF and B-RAF.

(A and B) Recombinant GST-RBD (AA 1–149) of c-RAF (A) or kinase domain (KD) of c-RAF (AA 306–648) (B) were subjected to DSF in the presence of DMSO (control), rigosertib (RGS), or PLX4032 (PLX). GST-RBD and KD reactions were performed in triplicate and duplicate, respectively.

(C) Binding of RGS to GST-RBD. GST-RBD was mixed with total cell lysates and incubated with RGS-biotin conjugate and streptavidin-agarose beads. The precipitates were subjected to western blot analysis using GST-specific antibodies.

(D) GST-KD was mixed with total cell lysates and incubated with RGS-biotin conjugate and streptavidin-agarose beads. The precipitates were processed as described for GST-RBD.

(E and F) Microscale thermophoretic analysis of RGS interaction with c-RAF and B-RAF RBDs. N-terminally labeled recombinant GST-tagged B-RAF and c-RAF RBD proteins were incubated with increasing concentrations of RGS and the binding reactions subjected to MST. RGS binds to the B-RAF and c-RAF RBDs with Kd values of 0.71 nM and 0.18 nM, respectively.

See also Figures S1, S4, and S5.

To confirm the interaction of RGS with the c-RAF RBD, we mixed recombinant GST-RAF RBD or GST-RAF KD with total HeLa cell lysates, incubated the extracts with biotin-RGS conjugate, and the bound proteins subjected to western blot analysis using anti-GST antibodies. The biotin-RGS conjugate readily pulled down the GST-RBD protein in a concentration-dependent manner while the GST-KD protein failed to do so (Figures 1C and 1D). Similarly, RGS was also shown to bind to B-RAF and A-RAF RBDs (Figures S1F and S1G).

We next determined the binding affinity of RGS to RAF-RBDs using microscale thermophoresis (MST) (Wienken et al., 2010). Highly purified preparations of recombinant c-RAF and B-RAF RBDs were fluorescently labeled at their N termini and a fixed concentration (100 nM) of each labeled protein was mixed with increasing concentrations of RGS (0.038–1,250 nM) and subjected to MST. The Kd values obtained from this analysis showed that RGS binds to the c-RAF and B-RAF RBDs with dissociation constants of 0.18 nM and 0.71 nM, respectively, demonstrating high-affinity binding (Figures 1E and 1F).

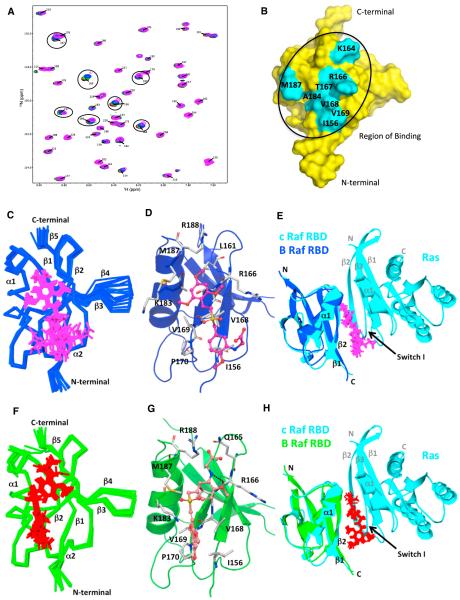

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Analysis of the B-RAF RBD-Rigosertib Interaction

To identify residues in the B-RAF RBD that interact with RGS, we recorded a series of 15N-1H heteronuclear single-quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of 15N-labeled B-RAF RBD with increasing concentrations of RGS (Figure 2A). Figure 2B shows the residues with the largest chemical shift perturbations (>3σ from the mean; Figure S2A) mapped on the surface of the lowest energy structure of the B-RAF RBD. Strikingly, the chemical shift perturbations caused by the addition of RGS are localized to the very region of the B-RAF-RBD implicated in RAS binding, namely the β1 and β2 strands and helix α1 (Nassar et al., 1995). Additionally, the cluster of residues with the largest chemical shift perturbation contains many of the same residues involved in RAS binding, namely I156, K164, R166, T167, V168, A184, and M187. These key residues are conserved within the RAF-RBDs, suggesting that RGS would bind to similar regions of A-RAF and c-RAF (Figure 3A).

Figure 2. NMR Analysis of the B-RAF RBD-Rigosertib Interaction: Chemical Shift Perturbation Studies and NMR Structure.

(A) Expanded view of the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the titration of RGS with 15N-labeled B-RAF RBD. Overlaid 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled B-RAF RBD with increasing concentrations of RGS: 0 (black), 0.25 (red), 0.5 (green), 1 (blue), 2 (magenta) mM.

(B) Surface representation of the B-RAF RBD (apo structure) showing the residues affected by RGS. Residues that show significant NMR chemical shifts (>3σ from mean) are labeled and shown in cyan.

(C and F) Superimposition of ten lowest energy complex structures of the B-RAF RBD (153–228) with RGS for complex I (blue/magenta) (C) and complex II (green/ red) (F).

(D and G) Ribbon plot showing the lowest energy structure of the B-RAF RBD with RGS in complex I (D) and complex II (G). Residues interacting with RGS are denoted in stick and gray color. Dotted line denotes hydrogen bonding.

(E and H) Superimposition of the lowest energy complex structures of B-RAF RBD:RGS with c-RAF RBD:Ras X-ray co-crystal structure (PBD: 4G0N). ComplexI (blue) with RGS (magenta) and c-RAF RBD:Ras complex (cyan) is shown in (E). Complex II (green) with RGS (red) and c-RAF RBD:Ras complex (cyan) is shown in

(H). Backbone RMSD between B-RAF RBD in complex I and complex II with c-RAF RBD in the crystal structure (PDB: 4G0N) is 1.15 Å.

See also Figure S2 and Table S1.

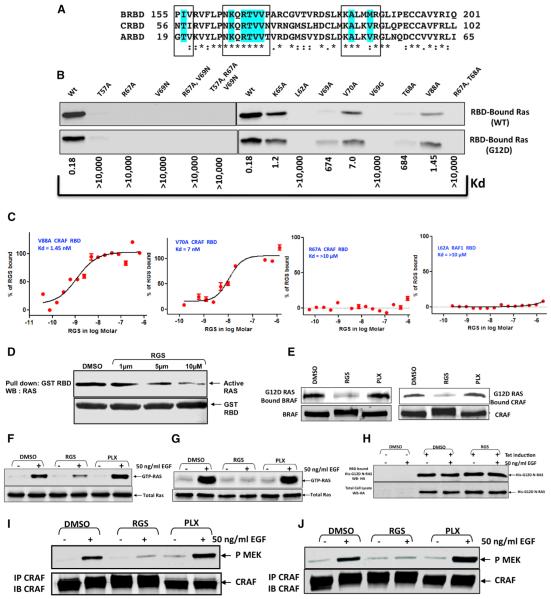

Figure 3. Rigosertib Interacts with the β1 Strand, β2 Strand, and α1 Helix of the B-RAF RBD, Interferes with the Binding of Active RAS with the RAF-RBD, and Inhibits RAS-Mediated Activation of RAF Kinase Activity.

(A) Alignment of the three RAF RBDs showing the residues in contact with RGS that are highlighted in cyan.

(B) Effect of RBD mutations on c-RAF-RBD:RAS interaction. HeLa cells (WT) or HeLa cells expressing a mutant form of RAS (G12D) were serum starved for 18 hr and stimulated with EGF for 5 min. The level of GTP-bound RAS in the cell lysates was tested for its ability to bind to WT c-RAF RBD and the indicated mutants. The same mutants were examined for their ability to bind to RGS using MST. Kd values for the mutants are provided below the blot.

(C) Four representative titration curves are shown.

(D) A431 cells were serum starved for 18 hr and treated with EGF and cell lysates analyzed for the level of RAS-GTP binding to the c-RAF RBD that was pre-incubated with DMSO or increasing concentrations of RGS for overnight.

(E) Exponentially growing HeLa cells were treated overnight with DMSO, RGS, or PLX4032 (PLX) and the cell lysates incubated for 2–4 hr at 4° C with agarose beads linked to GST-RasG12D. After extensive washing, the complexes were examined by immunoblot analysis using B-RAF or c-RAF antibodies. The levels of RAF proteins in the whole cell extracts are also shown.

(F and G) HeLa (F) or A431 (G) cells were serum starved for 18 hr in the presence of DMSO, RGS, or PLX, treated with EGF and the levels of RAS-GTP in cell lysates were determined using GST-RAF1-RBD and glutathione beads in pull-down assays.

(H) HeLa cells expressing N-RAS (G12D) were treated as in (F). The level of binding of G12D-N-RAS-GTP with the c-RAF RBD is shown.

(I and J) HeLa (I) and A431(J) cell lysates from (F) and (G) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-RAF antibodies and the immunoprecipitates analyzed for RAF kinase activity using kinase-inactive recombinant MEK protein as a substrate.

See also Figure S2 and Table S1.

To obtain more precise information about the mode of RGS binding, we solved the solution structures of B-RAF RBD and B-RAF RBD:RGS complex using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Figure 2; Table S1). The B-RAF RBD ensemble forms a tight cluster and consists of the α/β fold containing two α helices (177–186 and 214–217) and five b strands (156–160, 167–170, 195–201, 204–208, and 221–226). The mean backbone root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the ensemble with respect to the average structure is 0.50 ± 0.11 Å. The B-RAF RBD (apo) structure (PDB: 5J17) is very similar to the previously solved solution structure (http://www.rcsb.org/ pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=2L05) (PDB: 2L05) at low pH and the crystal structure of c-RAF RBD in complex with RAS (PDB: 4G0N) (Fetics et al., 2015), with backbone RMSD of 1.15 AÅ and 1.01 Å, respectively.

Intermolecular nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) observed between the B-RAF RBD and RGS indicate the presence of two binding positions of RGS (Figure S2E). Figures 2C and 2F show the ten lowest energy structure ensemble of B-RAF RBD:RGS complex, where RGS is bound to B-RAF RBD in two different orientations, namely complex I (PDB: 5J18) and II (PDB: 5J2R), respectively. The structure calculation of complex I and II were performed independently using the unique sets of NOEs that can only satisfy one or the other orientation. For example, Figure S2 (lower right panel) shows NOEs that are unambiguously assigned to complex I (magenta) and complex II (red). In both complexes, RGS binds at the same interface, namely α1 and β2 strands and helix α1 of B-RAF RBD (Figures 2D and 2G). The pairwise backbone RMSD from the mean structure for complex I and II are 0.60 ± 0.16 and 0.62 ± 0.18 Å, respectively, indicating no major deviation of the backbone atoms between the ten lowest energy structures within each complex. Superimposition of the lowest energy structure of the B-RAF RBD (apo) with the structure of the B-RAF RBD:RGS complex gives a RMSD of 0.88 Å (for all backbone atoms) for complex I and 0.87 Å for complex II, suggesting that there are no major conformational changes in the structure of the B-RAF RBD upon RGS binding (Figure S2B).

In both complexes, the intermolecular contacts are primarily hydrophobic in nature. In complex I, the trimethoxy styryl portion of RGS is oriented toward strand β2 and helix α1 and makes contacts with amino acids emanating from these two secondary structures, namely R166, T167, V168, and V169 from strand b2 and K183, A184, M187, and R188 from helix α1 (Figures 2D and S2C). In addition, L161 from strand b1 reaches over to contact one of the methoxy groups. The methoxy benzyl sulfone portion of RGS is less tightly clustered due to the lack of strong intermolecular NOEs. Contacts are primarily from K154 and I156 on strand β1and V168 and P170 on strand β2. In complex II, RGS is flipped 180° relative to the orientation observed in complex I, such that the methoxy benzyl sulfone portion of the drug now lies close to strand β2 and helix α1 and the trimethoxy styryl portion is in contact with strands β1 and β2. Overall, the drug is more tightly clustered than in complex I, reflecting a more uniform distribution of intermolecular NOEs across the length of the drug (Figure 2F). The trimethoxy styryl region is fixed by hydrophobic contacts with Lys154 and Ile156 from strand β1 and V168, V169, and P170 from strand β2. The only contacts from helix α1 are from Lys183 that extends over to one of the methoxy groups (Figures 2G and S2D). The methoxy benzyl sulfone portion of RGS is stabilized by contacts with R166, T167, V168 from strand β2, Leu161 from strand β1, and M187 and R188 from helix α1. All of these amino acids are involved in hydrophobic van der Waals interactions with the exception of R188. The guanidino group of R188 can potentially make a salt link with the glycine portion of RGS.

Overall, our NMR results show that RGS binds B-RAF RBD in two different orientations. Importantly, in both ensembles, RGS occupies the same interface and would occlude the binding of RAS to RAF RBDs (Figures 2E and 2H). Based on the distribution of NOEs observed in both ensembles, it is expected that both orientations are evenly populated in solution. Taken together, the NMR data provide powerful evidence that RGS binds the B-RAF RBD at essentially the same location as the RAS switch I region and can thereby preclude RAS-RAF interaction in cells (Figures 3A–3C).

Mutations in c-RAF-RBD that Affect RAS Binding Also Affect Rigosertib Binding

To further confirm that RGS and RAS bind to the same region of the RAF-RBDs, we created a number of mutant c-RAF RBDs and tested their ability to bind to GTP-RAS and RGS. These studies (Figures 3B and 3C) show that any mutation in the RAF-RBD that abolished the binding of RAS (WT and G12D K-RAS) also disrupted binding to RGS. These mutations include T57A, R67A, L62A, V69A, V69G, and T68A. Mutant RBDs (K65A, V69A, V70A, and V88A), which showed reduced binding affinities for RAS, also exhibited reduced binding affinities to RGS as indicated by their increased Kd values in MST (Figures 3B and 3C). These mutagenesis studies, combined with the NMR data, strongly suggest that RGS acts as a small molecule mimetic of RAS.

Effect of Rigosertib on RAS-RAF Interaction and RAF Kinase Activity

To examine whether RGS inhibits the interaction between GTP-RAS and CRAF-RBD in vitro, we stimulated serum-starved A431 cells with EGF (that activates RAS) and incubated the cell lysates with GST-RBD that was pre-incubated with either DMSO or increasing concentrations of RGS. The resulting complexes were precipitated using glutathione-agarose beads and subjected to western blot analysis for GTP-RAS. The results (Figure 3D) show that pre-incubation of GST-RBD with RGS results in an inhibition of its association with activated RAS in a concentration-dependent manner.

In the next set of experiments, lysates from HeLa cells that were treated overnight with DMSO, RGS (2 mM), or PLX4032 (2 mM) were incubated with GST-RASG12D agarose beads, (McKay et al., 2011) and the levels of endogenous c-RAF and B-RAF bound to these complexes were examined by immunoblot analysis. Treatment of cells with RGS resulted in an inability of the B-RAF and c-RAF proteins to bind to activated GST-RASG12D. In contrast, lysates derived from DMSO- or PLX4032-treated cells showed strong associations of c-RAF and B-RAF with GST-RASG12D (Figure 3E). These results support the hypothesis that RGS interferes with the ability of activated RAS to bind to RAF proteins.

To study the effects of RGS on EGF-induced activation of RAS and RAF, we used HeLa and A431 cell lines, both of which express wild-type RAS and RAF proteins. These cells were serum-starved in the presence of DMSO, RGS (2 μM), or PLX4032 (2 μM), stimulated with EGF, and the level of activated RAS determined using an active RAS pull-down kit. This assay utilizes a GST-RAF-RBD protein (that specifically binds to GTP-RAS) that can be pulled down by glutathione agarose beads (Taylor et al., 2001). As expected, RAS was activated upon EGF stimulation in both cell lines, and GTP-RAS could readily be pulled down by GST-RBD in DMSO and PLX4032-treated cells (Figures 3F and 3G). Surprisingly, very little or no GTP-RAS could be precipitated from lysates derived from cells treated with RGS, suggesting that RGS may interfere with the activation of WT-RAS by EGF.

To rule out the possibility that RGS interferes with RAS activation, we examined the effects of RGS on the activation of mutant RAS using a HeLa cell line that expresses a HA-tagged mutant N-RAS G12D protein (Figure 3H). Serum-starved cells grown in the presence or absence of RGS were stimulated with EGF and the level of mutant RAS-GTP complexes bound to GST-RBD determined. The results (Figure 3H) show that pre-incubation of cells with RGS had no effect on the levels of GTP-RAS. In fact, these cells were found to constitutively express GTP-bound mutant RAS in the absence of any EGF stimulation. These studies suggest that RGS interferes with the ability of RAF to interact with active WT-RAS, which might result in its rapid conversion to its GDP-bound form. It is unlikely that the presence of RGS in cell lysates interferes with the binding of GTP-RAS to RBD since we used a high excess of GST-RBD in these assays and the cell lysates contain very small amounts of RGS, which is highly diluted by the lysis buffer.

Since growth factor-mediated RAS-RAF association results in the activation of RAF kinase activity (Diaz et al., 1997), we examined the effects of RGS on the catalytic activity of RAF proteins in EGF-stimulated cells. The results of this study (Figures 3I and 3J) demonstrate that pre-treatment of cells with RGS inhibits EGF-induced activation of RAF kinase activity, while pre-treatment with PLX4032 results in its enhancement. Because RGS does not inhibit the kinase activity of any of the three RAF proteins in in vitro assays (Figure S3), we conclude that absence of c-RAF kinase activity in RGS-treated cells is indirect and is due to inhibition of RAS-RAF interaction that is required for the RAF protein to assume a kinase-active conformation.

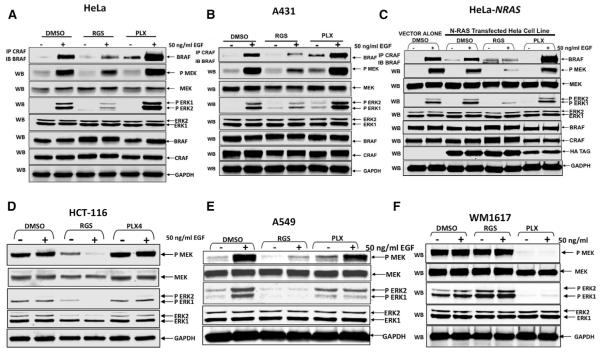

Rigosertib Inhibits RAF Heterodimerization and MAPK Signaling

To test the effects of RGS on RAF-mediated signaling, we examined the effects of RGS on heterodimerization of endogenous c-RAF and B-RAF in response to EGF-stimulation by performing co-immunoprecipitation assays using c-RAF-specific antibodies and determining the level of associated B-RAF by western blot analysis. While little or no association between the two RAF proteins was detected in serum-starved cells that were treated with DMSO (no EGF), EGF stimulation readily induced the formation of c-RAF and B-RAF heterodimers (Figures 4A and 4B). However, simultaneous treatment with RGS resulted in a nearly complete inhibition of c-RAF/B-RAF heterodimer formation. In contrast, PLX4032 treatment enhanced the association between the two RAF proteins, as previously reported (Hu et al., 2013).

Figure 4. Rigosertib Interferes with Growth Factor-Induced RAF Dimerization and MEK/ERK Activation.

(A–F) HeLa (A) or A431 (B) cells were serum starved for 18 hr in the presence of DMSO, RGS, or PLX, treated with EGF and cell lysates subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-RAF antibodies and the level of associated B-RAF determined by western blot analysis. The level of ERK, phospho-ERK, MEK, phospho-MEK, total c-RAF and B-RAF, and GAPDH (loading control) were also determined by western blot analysis. The effect of DMSO, RGS, or PLX on EGF-induced RAF dimerization and/or activation of MEK and ERK in HeLa (C) cells transfected with a vector control or HA-tagged, N-RAS (G12D) expression vector HCT-116 (D) and A549 (E) and WM1617 (F) cells were determined as described above.

See also Figure S3.

Because growth factor-mediated activation of RAF is known to activate the MEK/ERK pathway (Pylayeva-Gupta et al., 2011; Ritt et al., 2010), we next examined the effect of RGS and PLX4032 on the phosphorylation status of MEK and ERK and observed a reduction in MEK and ERK phosphorylation in both HeLa and A431 cells treated with RGS (Figures 4A and 4B). In contrast, a small increase or no change in the phosphorylation status of these proteins was detected in PLX4032-treated cells.

Next, we performed similar experiments using N-RAS (G12D)-expressing HeLa cells as well as HCT-116 and A549 cells that harbor a point mutation in the K-RAS gene. The results show that RGS inhibits MEK and ERK activation equally well, indicating that RGS inhibits both wild-type and mutant RAS-mediated signaling (Figures 4C–4E). As a negative control, we examined the effects of RGS and PLX4032 on the human WM-1617 melanoma cell line that harbors a V599E mutation in the BRAF gene that results in RAS-independent activation of MAPK signaling (Satyamoorthy et al., 2003). When these cells were treated with RGS, little or no inhibition of ERK or MAPK phosphorylation was observed while PLX4032 could completely block these phosphorylation events (Figure 4F). These results are consistent with RGS inhibiting the MEK/ERK pathway by inhibiting RAS-RAF interaction.

Rigosertib Inhibits c-RAFSer338 Phosphorylation

It is now well established that growth factor-mediated stimulation of c-RAF kinase activity is accompanied by phosphorylation of Ser338 (Diaz et al., 1997). To determine if RGS affects the phosphorylation of c-RAFSer338, HCT116 cells were serum-starved in the presence of DMSO, RGS, or PLX4032 and stimulated with EGF for 5 min. The results presented in Figure 5A show the high levels of Ser338 phosphorylation in DMSO-treated cells following EGF stimulation. While little or no effect was seen in cells treated with PLX4032, RGS treatment completely inhibited EGF-induced c-RAFSer338 phosphorylation (Figure 5A).

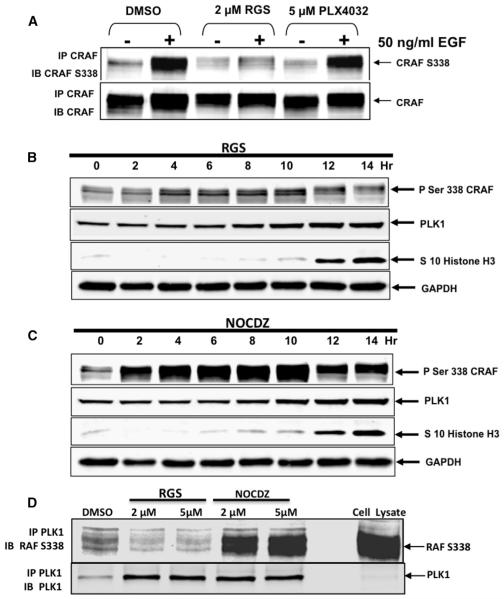

Figure 5. Treatment of Human Tumor Cells with Rigosertib Inhibits c-RAFSer338 Phosphorylation and Inhibits PLK-1:RAF Interaction.

(A) HCT116 cells were serum-starved in the presence of DMSO, RGS, or PLX, stimulated with EGF and the lysates subjected to immunoprecipitation using a c-RAF-specific antibody. The immunoprecipitates were subjected to western blot analysis using c-RAF and c-RAFSer338 antisera.

(B and C) HCT 116 cells were blocked at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block, released into growth medium containing RGS or nocadazole (NOCDZ), and the levels of c-RAFSer338, PLK1, and histone H3Ser10 were determined by western blot analysis. Note the accumulation of c-RAFSer338 in cells treated with nocadazole as the cells progress toward mitosis, which is drastically reduced in RGS-treated cells.

(D) Cell lysates isolated from RGS- or nocodazole-treated cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation using a PLK1-specific antibody and the level of associated c-RAFSer338 determined by western blot analysis.

Effect of Rigosertib on RAF-PLK1 Interactions

Unlike many RAF inhibitors that induce G1 arrest, treatment with RGS causes tumor cells to undergo growth arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Reddy et al., 2011). While RGS was originally described as a PLK1 inhibitor (Gumireddy et al., 2005), subsequent experiments by us and others (Steegmaier et al., 2007) showed that RGS does not directly inhibit PLK1 kinase activity. Inhibition of c-RAFSer338 phosphorylation inhibits association of c-RAF with PLK1, leading to spindle abnormalities and a subsequent block in mitotic progression (Mielgo et al., 2011). Since RGS treatment also causes spindle abnormalities and mitotic block, we investigated whether treatment of exponentially growing cells with RGS inhibits c-RAFSer388 phosphorylation and, consequently, its association with PLK1. HCT116 cells were synchronized at the G1/S boundary using a double thymidine block and released into growth medium containing either RGS or nocodazole, since both compounds induce mitotic arrest. Mitosis-specific histone H3Ser10 phosphorylation (Paulson and Taylor, 1982), was used as a surrogate marker of cell-cycle progression. The results presented in Figures 5B and 5C show that both RGS- and nocodazole-treated cells enter mitosis as reflected by the accumulation of phosphorylated Ser10-histone H3 that was accompanied by an accumulation of phosphorylated c-RAFSer338 in nocadazole-treated cells, whereas this phosphorylation was reduced by 90% in cells treated with RGS. We next asked whether treatment with nocodazole or RGS affected the interaction of PLK-1 with c-RAFSer338 by immunoprecipitating cell lysates with anti-PLK1 antibodies and subjecting the immunoprecipitates to western blot analysis using antibodies directed against c-RAFSer338. The results presented in Figure 5D show that while there is a strong association of PLK1 with c-RAFSer338 in cells treated with nocadazole, there was little or no association of PLK1 with this protein in RGS-treated cells. These results show that RGS can inhibit some functions of PLK1 that lead to mitotic arrest of tumor cells by inhibiting PLK1/RAF interactions.

Rigosertib Binds to RBDs of Ral-GDS and PI3Ks

RBDs adopt similar, ubiquitin-like folds despite the lack of extensive sequence similarity (Kiel et al., 2005; Wohlgemuth et al., 2005), suggesting that RGS might bind to the RBDs of multiple effector proteins and inhibit several RAS-driven signaling pathways. To test this possibility, we examined the ability of RGS to bind to RBDs of RalGDS and PI3Ks. DSF studies as well pull-down assays with biotin-RGS conjugate showed that RGS binds to recombinant Ral-GDS RBD, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure S4).

Recombinant PI3K RBD proteins are highly insoluble and unsuitable for DSF assays. As an alternative, we expressed the four class I PI3K-RBDs in HEK293T cells and performed pull-down assays using increasing concentrations of biotin-RGS conjugate. We readily observed concentration-dependent pull-downs of the PI3Kα, PI3Kβ and PI3Kγ RBDs; however, the interaction of PI3Kδ-RBD with biotin-RGS was weak, suggesting that RGS does not have a high affinity for this RBD (Figure S5A). Because growth factor-mediated activation of PI3K is known to activate the AKT pathway (Burgering and Coffer, 1995), we tested the effects of RGS on AKT phosphorylation in EGF-stimulated MIAPaCa-2, HCT-116, and MDA-MB-231 cells, all of which express mutant KRAS. The results presented in Figure S5B show a reduction in AKT phosphorylation in all three cell lines treated with RGS, suggesting that it inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway by inhibiting RAS-PI3K interaction.

Rigosertib Inhibits RAS-Mediated Transformation and Tumor Growth

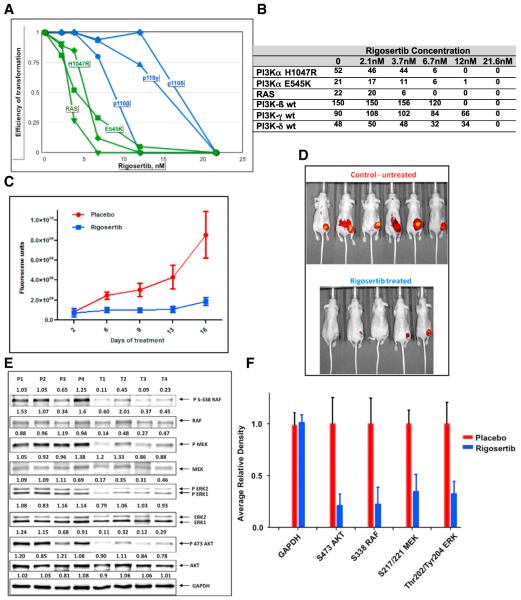

The effects of RGS on oncogenic transformation mediated by mutant RAS and PI3Ks was evaluated by transformation assays using avian fibroblasts expressing the oncogenic H-RAS-G12V, p110α-E545K, p110α-H1047R, WT PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ, or p110δ. RGS inhibited transformation by all of these oncogenic proteins with IC50 values between 6–15 nM, suggesting that this compound has potent anti-oncogenic activity (Figures 6A and 6B). Interestingly, in these assays, RGS was more effective in inhibiting the transforming activity of mutant RAS and p110α-E545K and p110α-H1047R compared to WT PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ, or p110δ.

Figure 6. Rigosertib Inhibits RAS-Mediated Transformation and Tumor Growth.

(A) Rigosertib inhibits transformation of chicken fibroblasts (CEFs) by mutant RAS, p110α-E545K, p110α-H1047R, PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ, and PI3Kδ. CEFs were transfected with RCAS virus expressing the indicated oncogene in the presence of increasing concentrations of RGS. The plates were overlaid with nutrient agar every other day for 2–3 weeks post-infection. Transformation values are represented in graphical form.

(B) The absolute level of colony formation by each of these constructs in the absence or presence of RGS.

(C) Growth of HCT116 xenograft tumors in vehicle or RGS-treated ncr/ncr mice as measured using Transferrin-Vivo 750 imaging agent. Fluorescence units are shown.

(D) Florescence images of the mice on day 16.

(E) Tumor extracts derived from placebo and RGS-treated mice were subjected to western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

(F) Average values of each phospho protein are shown in graphical form.

See also Figure S6.

To determine the in vivo efficacy of RGS in the context of mutant RAS, we used three different biological models, two xenograft models of human colorectal cancer, HCT116 (K-RASG13D) and lung cancer, A549 (K-RASG12S), and genetically modified mouse model (GEMM) of pancreatic cancer (K-RASG12D). In the nude mouse model, HCT116 or A549 cells were injected into nude mice, and the tumors were allowed to grow to ~100 mm3 in size and treated daily with either water (vehicle) or RGS (100 mg/kg) twice daily for 16 days. Growth of the tumors was monitored using Transferrin vivo 750 imaging agent (Figure 6D). The results presented in Figures 6C, 6D, S6A, and S6B show that RGS treatment resulted in dramatically decreased tumor growth in both tumor models.

To confirm that the growth inhibition of tumors is associated with inhibition of RAS signaling, we examined the effects on RAS-mediated MEK/ERK signaling in extracts derived from four placebo- and RGS-treated tumors. Figures 6E, 6F, and S6C show that while there is robust activation of the ERK and PI3K pathways in placebo-treated tumors as evidenced by c-RAFSer338, MEK, ERK, and AKT phosphorylation, these phosphorylation events were dramatically reduced in tumors obtained from rigosertib-treated animals suggesting that RGS is an effective inhibitor of the MAPK and PI3K pathways.

Inhibition of RAS-Signaling by Rigosertib Suppresses Pancreatic Tumorigenesis

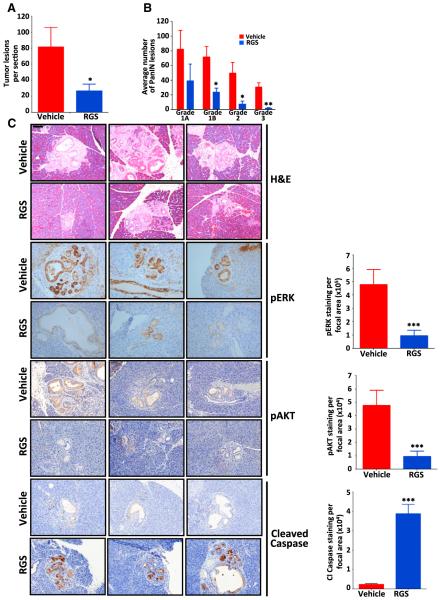

We next investigated the effects of RGS treatment on tumor maintenance in vivo using the Pdx-cre:Kras+/LSL G12D mouse model of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) (Hingorani et al., 2003) that develops pancreatic ductal lesions that mirror human PanINs. For these studies, cohorts of Pdx-cre:Kras+/ G12D mice at 3.5 months of age were treated twice daily with either vehicle (PBS) or 200 mg/kg RGS for a period of 14 days. At the end of the study, pancreata were removed and the number and grade of PanINs determined histologically. As shown in Figure 7A, the number of pancreatic lesions in the RGS-treated animals was ~3-fold less than that of the placebo-treated group. Furthermore, quantification and classification of the lesions according to grade revealed dramatic differences in the number of PanIN 1B, 2, and 3 grade tumors between placebo- and RGS-treated animals, with the decrease in these lesions being statistically significant (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Treatment with Rigosertib Suppresses the Growth of RAS-Driven Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia.

(A and B) Average number of PanINs per section

(A) and total number of PanINs by grade (B) in vehicle- and RGS-treated animals.

(C) Representative hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical staining of representative pancreatic sections harvested from three vehicle- and RGS-treated mice. Scale bar, 100 mm. Average levels of ERK and AKTSer473 phosphorylation and caspase-3 cleavage in PanINs are also represented graphically. All values represent mean ± SD; n ≥ 3 for each treatment group. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.005.

See also Figure S5.

To confirm that suppression of RAS-mediated signaling correlated with response to RGS, we examined the levels of ERK and AKTSer473 phosphorylation within the PanINs using immunohistochemical analysis. As predicted, while there was robust staining of phosphorylated ERK and AKTSer473 in the control tumors, the tumors isolated from RGS-treated animals exhibited markedly decreased levels of both phosphoproteins, indicating that treatment with this compound reduced the level of RAS-mediated signaling in these lesions (Figure 7C). Examination of the degree of caspase-3 cleavage in the pancreata isolated from control and RGS-treated mice revealed that the level of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells was nearly 4-fold greater in the PanIN lesions of RGS-treated animals (Figure 7C). Together, these studies demonstrate the effectiveness of RGS in the treatment of RAS-driven tumors.

DISCUSSION

It is now well established that a majority of human tumor cells exhibit aberrant RAS signaling either due to mutations in the RAS genes themselves, or mutations in the growth factor receptors and effector molecules that transmit RAS signals. Although there has been considerable effort to identify inhibitors of RAS signaling, no effective anti-RAS therapeutics have reached the clinic so far.

Here, we present evidence that rigosertib, a compound currently in clinical trials, has the ability to interact with the RBDs of RAF family proteins and effectively blocks RAS signaling. We could demonstrate rigosertib’s ability to bind to the B-RAF RBD by a number of biophysical methods, including DSF, MST, and NMR spectroscopy. We have solved the solution structures of B-RAF RBD and its complex with RGS (Figures 2 and S2; Table S1), and we show that RGS binds B-RAF RBD in two different orientations but occupies the same interface that will occlude the binding of RAS switch I region to RAF RBDs (Figures 2E and 2H). Accordingly, we find that mutations on this surface that abolish the binding of RGS to RAF-RBD also abolish RAS binding. Furthermore, mutations such as K65A, V70A and V88A, which reduce the binding affinity of RGS also reduce affinity for RAS (Figures 3A and 3B). Collectively, these observations point to RGS functioning as an almost perfect RAS-mimetic that prevents RAS from interacting with its downstream effectors.

In agreement with the above findings, we observed a strong block in growth factor-induced RAF activation due to the inability of B-RAF and C-RAF to bind activated RAS in RGS-treated cells. One consequence of RGS-mediated inhibition of RAS-RAF interactions is an inability to form RAF dimers and an inhibition of MEK and ERK signaling. We show here that RGS has a dual action in inhibiting the phosphorylation of c-RAF Ser338 and its association with PLK1 (Figure 5), which leads to the mitotic arrest of tumor cells. Our studies also show that RGS binds to other RAS effectors, including RalGDS and members of the PI3 kinase family, via their RBDs and inhibits transformation mediated by oncogenic RAS and PI3K proteins (Figure 6). Because the RBDs of most RAS effectors adopt similar, ubiquitin-like folds that have nearly identical tertiary structures suggest that RGS might be able bind and inhibit multiple RAS-driven signaling pathways.

In vivo efficacy studies using the HCT116 and A549 xenograft models of colorectal and lung cancers show that RGS is a potent inhibitor of tumor growth, which is accompanied by downregulation of MAPK and PI3K signaling (Figure 6). The ability of RGS to inhibit tumor growth in vivo was also demonstrated using a K-rasG12D GEMM of PanIN, whereby mice treated with RGS exhibited a reduction in tumor burden that correlated with reductions in RAS-mediated signaling and an increase in apoptosis (Figure 7). In a recent phase III clinical trial, a group of MDS patients with monosomy 7 and trisomy 8, two cytogenetic abnormalities that are associated with RAS activation in ~50% of cases, (de Souza Fernandez et al., 1998; Stephenson et al., 1995) responded best to treatment with RGS, with hazard ratio for survival in the 0.25–0.30 range (Garcia-Manero et al., 2016). These results further support the value of RGS in treating patients with abnormalities in the RAS pathway. There have been many attempts to inhibit MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways using a combination of inhibitors, which have generally failed to show an acceptable therapeutic index due to combined toxicity exhibited by these drugs. Rigosertib, as a single agent, has shown a remarkable safety profile in spite of inhibiting multiple signaling pathways, which appears to be due to its unique mechanism of action.

The human genome encodes a large number of RAS-related proteins, several of which are members of the heterotrimeric G protein gene family. Like RAS, these proteins mediate their effects by binding to their effectors via their RBD-like domains. The strategy presented here of inactivating RAS signaling based on inhibition of RAS interaction with downstream effectors may be similarly applied to this large family of G proteins, paving the way for a new class of drugs for the treatment of G protein-mediated diseases.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

In Vitro Pull-Down Assays

To identify RGS-binding proteins, cell lysates were pre-cleared with streptavidin-agarose beads and incubated with RGS-biotin conjugate and neutravidin agarose and the samples overnight at 4° C. The precipitates subjected to SDS-PAGE and individual bands were excised and subjected to mass spectrometry.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

RBD-containing proteins were combined with the indicated concentrations of DMSO, RGS, or PLX-4032 in Protein Thermal Shift Buffer (Applied Biosciences). Melt reactions were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Structure Calculation

13C-15N-labeled B-RAF RBD (aa 151–230) was used for backbone and side chain resonance assignments as previously described (Delaglio et al., 1995; Johnson, 2004) (see also the Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Back-bone resonance assignments data were collected with a 30% sampling schedule using non-uniform sampling versions of HNCO/HN(CA)CO, HNCA/ HN(CO)CA, and HNCACB/CBCACONH pairs of experiments. Inter-molecular NOEs were obtained from aliphatic 1H-13C filtered NOESY-HSQC experiments. Mixing times of 150 and 200 ms were used in the NOESY-HSQC experiments for determining the B-RAF RBD and B-RAF RBD:RGS structures, respectively.

To determine the B-RAF:RGS binding interface, spectral perturbation in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of the B-RAF RBD protein were obtained using separate titrations with increasing concentrations of RGS dissolved in NMR buffer.

Structure calculations were carried out using distance, dihedral and hydrogen-bond constraints using the program ARIA/CNS. A total of 2,016, 1,895, and 1,893 restraints were used to solve the structure of B-RAF RBD, B-RAF RBD:rigosertib complex I, and complex II, respectively (Table S1). The complex structures were calculated independently with inter-molecular NOEs, which were unique to complex I and II. The ten lowest energy structures with no distance (>0.5 Å) and dihedral violations (>5 Å) were chosen to represent the structure ensemble. Additional details can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Microscale Thermophoresis

Proteins were N-terminally labeled using the Monolith NT Protein Labeling Kit RED-NHS (Nano-Temper Technologies) and 100 nM of labeled GST-tagged B-RAF (aa 151–230) or c-RAF (aa 1–149) proteins were incubated with increasing concentrations of RGS for 30 min at room temperature and fluorescence values from the binding reactions were determined using the Monolith NT.115 (Nano Temper Technologies). Binding data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Additional details are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Animal Studies

All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s and Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees according to federal, state and institutional guidelines and regulations.

Tumor cells were implanted subcutaneously and tumor-bearing animals were treated with rigosertib (100 mg/kg) or vehicle (PBS) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection twice daily for 16 days. Tumor volumes were monitored using Transferrin vivo 750 imaging agent (Perkin Elmer) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Kras+/LSL G12D mice (Jackson et al., 2001) were crossed with the Pdx-cre mice (Hingorani et al., 2003). Pdx-cre:Kras+/G12D mice at 3.5 months of age were treated twice daily with either vehicle (PBS) or rigosertib (200 mg/kg) via i.p. injection for 14 days. Pancreata were isolated and sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin or subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. Additional details are provided in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Rigosertib binds to the RAS-binding domains (RBDs) of multiple RAS effectors

Binding of rigosertib to RAF-RBD inhibits RAS-RAF interaction and impairs the kinase

Rigosertib inhibits MEK-ERK pathway activated by growth factors and oncogenic RAS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Deborah Morrison (NCI) for material and intellectual help with the design and execution of some of these studies. E.P.R. was supported by grants from Onconova Therapeutics (OTI) and NIH CA158209. Data collection at New York Structural Biology Center (NYSBC) was supported by grants from NYSTAR, NIH CO6RR015495, NIH P41GM066354, and the Keck Foundation. P.K.V. was supported by NIH grants CA78230, CA151574, and CA153124. E.P.R. is a founder, paid consultant, and board member of OTI. R.V.-D.C., S.J.B., S.C.C., M.V.R., and A.K.A. are consultants for OTI.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The accession numbers for the coordinates for solution structures of B-RAF-RBD and complexes I and II reported in this paper are PDB: 5J17, 5J18, and 5J2R. The accession numbers for the NMR resonance assignments are BMRB: 30047 (B-RAF-RBD), 30048 (Complex I), and 30050 (Complex II).

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, six figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.045.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.K.A.-D. performed the binding, signaling, and animal studies. R.V.-D.C. performed protein purification, binding experiments, and assisted with NMR studies. K.D. designed the NMR studies, performed all structure calculations, analyzed the data, and assisted in writing the paper. S.J.B. carried out mutagenesis studies. S.C.C. and D.M. assisted with animal studies and analysis of tumor tissues. I.B. assisted with KrasG12D mouse studies. Y.K.G. assisted with protein purification. M.V.R. designed and synthesized RGS, biotin-RGS, and ON01911. L.U., J.R.H., and P.K.V. designed and performed CEF transformation studies. C.G. designed and analyzed KrasG12D mouse experiments. A.K.A. designed the structural studies, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. E.P.R. designed the studies, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- Agoni L, Basu I, Gupta S, Alfieri A, Gambino A, Goldberg GL, Reddy EP, Guha C. Rigosertib is a more effective radiosensitizer than cisplatin in concurrent chemoradiation treatment of cervical carcinoma, in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2014;88:1180–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block C, Janknecht R, Herrmann C, Nassar N, Wittinghofer A. Quantitative structure-activity analysis correlating Ras/Raf interaction in vitro to Raf activation in vivo. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:244–251. doi: 10.1038/nsb0396-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgering BM, Coffer PJ. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano E, Downward J. RAS interaction with PI3K: more than just another effector pathway. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:261–274. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Fernandez T, Menezes de Souza J, Macedo Silva ML, Tabak D, Abdelhay E. Correlation of N-ras point mutations with specific chromosomal abnormalities in primary myelodysplastic syndrome. Leuk. Res. 1998;22:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(97)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz B, Barnard D, Filson A, MacDonald S, King A, Marshall M. Phosphorylation of Raf-1 serine 338-serine 339 is an essential regulatory event for Ras-dependent activation and biological signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4509–4516. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetics SK, Guterres H, Kearney BM, Buhrman G, Ma B, Nussinov R, Mattos C. Allosteric effects of the oncogenic RasQ61L mutant on Raf-RBD. Structure. 2015;23:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Manero G, Fenaux P, Al-Kali A, Baer MR, Sekeres MA, Roboz GJ, Gaidano G, Scott BL, Greenberg P, Platzbecker U, et al. Rigosertib versus best supportive care for patients with high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes after failure of hypomethylating drugs (ONTIME): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00009-7. Published online March 8, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumireddy K, Reddy MV, Cosenza SC, Boominathan R, Baker SJ, Papathi N, Jiang J, Holland J, Reddy EP. ON01910, a non-ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor of Plk1, is a potent anticancer agent. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Ramjaun AR, Haiko P, Wang Y, Warne PH, Nicke B, Nye E, Stamp G, Alitalo K, Downward J. Binding of ras to phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110alpha is required for ras-driven tumorigenesis in mice. Cell. 2007;129:957–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Stites EC, Yu H, Germino EA, Meharena HS, Stork PJ, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Shaw AS. Allosteric activation of functionally asymmetric RAF kinase dimers. Cell. 2013;154:1036–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Hart JR, Ueno L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic activity of the regulatory subunit p85b of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16826–16829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420281111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Montoya R, Jacks T, Tuveson DA. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA. Using NMRView to visualize and analyze the NMR spectra of macromolecules. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;278:313–352. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel C, Wohlgemuth S, Rousseau F, Schymkowitz J, Ferkinghoff-Borg J, Wittinghofer F, Serrano L. Recognizing and defining true Ras binding domains II: in silico prediction based on homology modelling and energy calculations. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:759–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Ritt DA, Morrison DK. RAF inhibitor-induced KSR1/B-RAF binding and its effects on ERK cascade signaling. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielgo A, Seguin L, Huang M, Camargo MF, Anand S, Franovic A, Weis SM, Advani SJ, Murphy EA, Cheresh DA. A MEK-independent role for CRAF in mitosis and tumor progression. Nat. Med. 2011;17:1641–1645. doi: 10.1038/nm.2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar N, Horn G, Herrmann C, Scherer A, McCormick F, Wittinghofer A. The 2.2 A crystal structure of the Ras-binding domain of the serine/threonine kinase c-Raf1 in complex with Rap1A and a GTP analogue. Nature. 1995;375:554–560. doi: 10.1038/375554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2212–2221. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold ME, Suire S, Perisic O, Lara-Gonzalez S, Davis CT, Walker EH, Hawkins PT, Stephens L, Eccleston JF, Williams RL. Crystal structure and functional analysis of Ras binding to its effector phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma. Cell. 2000;103:931–943. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00196-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JR, Taylor SS. Phosphorylation of histones 1 and 3 and nonhistone high mobility group 14 by an endogenous kinase in HeLa metaphase chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:6064–6072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior IA, Lewis PD, Mattos C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2457–2467. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. RAS oncogenes: weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy EP. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene. Science. 1983;220:1061–1063. doi: 10.1126/science.6844927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy EP, Reynolds RK, Santos E, Barbacid M. A point mutation is responsible for the acquisition of transforming properties by the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene. Nature. 1982;300:149–152. doi: 10.1038/300149a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MV, Venkatapuram P, Mallireddigari MR, Pallela VR, Cosenza SC, Robell KA, Akula B, Hoffman BS, Reddy EP. Discovery of a clinical stage multi-kinase inhibitor sodium (E)-2-2-methoxy-5-[(2′ ,4′ ,6′ -trimethoxystyrylsulfonyl)methyl]phenylaminoacetate (ON 01910.Na): synthesis, structure-activity relationship, and biological activity. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:6254–6276. doi: 10.1021/jm200570p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritt DA, Monson DM, Specht SI, Morrison DK. Impact of feedback phosphorylation and Raf heterodimerization on normal and mutant B-Raf signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:806–819. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00569-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyamoorthy K, Li G, Gerrero MR, Brose MS, Volpe P, Weber BL, Van Belle P, Elder DE, Herlyn M. Constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in melanoma is mediated by both BRAF mutations and autocrine growth factor stimulation. Cancer Res. 2003;63:756–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu K, Birnbaum D, Ruley MA, Fasano O, Suard Y, Edlund L, Taparowsky E, Goldfarb M, Wigler M. Structure of the Ki-ras gene of the human lung carcinoma cell line Calu-1. Nature. 1983;304:497–500. doi: 10.1038/304497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steegmaier M, Hoffmann M, Baum A, Lénárt P, Petronczki M, Krssák M, Gürtler U, Garin-Chesa P, Lieb S, Quant J, et al. BI 2536, a potent and selective inhibitor of polo-like kinase 1, inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J, Lizhen H, Mufti GJ. Possible co-existence of RAS activation and monosomy 7 in the leukaemic transformation of myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Res. 1995;19:741–748. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(95)00056-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabin CJ, Bradley SM, Bargmann CI, Weinberg RA, Papageorge AG, Scolnick EM, Dhar R, Lowy DR, Chang EH. Mechanism of activation of a human oncogene. Nature. 1982;300:143–149. doi: 10.1038/300143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taparowsky E, Shimizu K, Goldfarb M, Wigler M. Structure and activation of the human N-ras gene. Cell. 1983;34:581–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90390-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SJ, Resnick RJ, Shalloway D. Nonradioactive determination of Ras-GTP levels using activated ras interaction assay. Methods Enzymol. 2001;333:333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)33067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada T, Ito Y, Shirouzu M, Tateno M, Hashimoto K, Kigawa T, Ebisuzaki T, Takio K, Shibata T, Yokoyama S, et al. Nuclear magnetic resonance and molecular dynamics studies on the interactions of the Rasbinding domain of Raf-1 with wild-type and mutant Ras proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;286:219–232. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, Zhang J, Cho H, Mamo S, Bremer R, Gillette S, Kong J, Haass NK, et al. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3041–3046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711741105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vojtek AB, Der CJ. Increasing complexity of the Ras signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:19925–19928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.19925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienken CJ, Baaske P, Rothbauer U, Braun D, Duhr S. Protein-binding assays in biological liquids using microscale thermophoresis. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:100. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth S, Kiel C, Krämer A, Serrano L, Wittinghofer F, Herrmann C. Recognizing and defining true Ras binding domains I: biochemical analysis. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:741–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa Y, Srivastava SK, Dunn CY, Rhim JS, Reddy EP, Aaronson SA. Acquisition of transforming properties by alternative point mutations within c-bas/has human proto-oncogene. Nature. 1983;303:775–779. doi: 10.1038/303775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.