Abstract

The Integrated Transport and Health Impact Model (ITHIM) is a comprehensive tool that estimates the hypothetical health effects of transportation mode shifts through changes to physical activity, air pollution, and injuries. The purpose of this paper is to describe the implementation of ITHIM in greater Nashville, Tennessee (USA), describe important lessons learned, and serve as an implementation guide for other practitioners and researchers interested in running ITHIM. As might be expected in other metropolitan areas in the US, not all the required calibration data was available locally. We utilized data from local, state, and federal sources to fulfill the 14 ITHIM calibration items, which include disease burdens, travel habits, physical activity participation, air pollution levels, and traffic injuries and fatalities. Three scenarios were developed that modeled stepwise increases in walking and bicycling, and one that modeled reductions in car travel. Cost savings estimates were calculated by scaling national-level, disease-specific direct treatment costs and indirect lost productivity costs to the greater Nashville population of approximately 1.5 million. Implementation required approximately one year of intermittent, part-time work. Across the range of scenarios, results suggested that 24 to 123 deaths per year could be averted in the region through a 1%–5% reduction in the burden of several chronic diseases. This translated into $10–$63 million in estimated direct and indirect cost savings per year. Implementing ITHIM in greater Nashville has provided local decision makers with important information on the potential health effects of transportation choices. Other jurisdictions interested in ITHIM might find the Nashville example as a useful guide to streamline the effort required to calibrate and run the model.

Introduction (1.0)

Transportation systems can impact health through changes in physical activity, injury, and air pollution mediated disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). These health pathways account for a large burden of mortality in the United States (Caizzo et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2012; United States Department of Transportation and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2015). Quantitative estimates of the net expected change in health status attributable to changes in future transportation behavior could help governments efficiently allocate resources and reduce health care costs. The Integrated Transport and Health Impact Model (ITHIM) is a relatively new, comprehensive tool that might fill this need (Woodcock et al., 2009). To date, ITHIM has been used infrequently in the United States, primarily in densely-populated areas on the West Coast (Iroz-Elardo et al., 2014; Maizlish et al., 2013). Implementations of ITHIM in sprawling metropolitan areas with diverse mixes of rural, suburban, and urban areas are lacking. Such a project could demonstrate ITHIM’s effectiveness across a range of settings and identify additional sources for calibration data.

The Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (NAMPO) is responsible for transportation planning for 1.5 million residents in seven counties in north central Tennessee (TN), which lies in the southeastern United States. Notably, this area has a high burden of chronic disease and associated risk factors (Yoon et al., 2014). The NAMPO has recognized transportation’s role in addressing these health concerns and is actively embracing public health concepts in transportation planning, influenced by support for active transportation (e.g. walking and bicycling) registered in public opinion surveys. For example, the NAMPO has adopted a project-selection scoring rubric where 80 of 100 points are dedicated to elements of Complete Streets design standards, thereby increasing substantially the number of funded projects that meet these standards. Further, the NAMPO has reserved 15% of its US Department of Transportation Surface Transportation Program allocation for active transportation infrastructure and education projects and 10% for public transit-related projects. The NAMPO elected to use ITHIM to estimate the potential health impacts of these initiatives that collectively aim to increase walking, bicycling, and transit use in the region. The outputs of the ITHIM model would also help the NAMPO educate stakeholders and the general public on the relationship between transportation and health.

ITHIM uses comparative risk assessments to estimate the health impacts of changing transportation behaviors through three pathways: physical activity, air pollution, and injuries (serious and fatal). By taking into account both potential benefits and harms, ITHIM provides a comprehensive estimate of health impacts not available in some other models (World Health Organization, 2014), but its comprehensiveness requires extensive calibration data. Early use of ITHIM in the US relied on robust transportation and health data from the state of California (Maizlish et al., 2013), and similar data are not uniformly available in other geographic areas. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to describe (a) the implementation, including model calibration, scenario development, and selected results, of ITHIM in greater Nashville and (b) important lessons learned during the process. In doing so, this paper might serve as an implementation guide for practitioners or researchers in other geographic areas, especially, but not limited to, other mid-sized US metropolitan areas.

Methods and Materials (2.0)

ITHIM Model (2.1)

Details on the development of and calculations within the ITHIM model have been previously published (Maizlish et al., 2013; Woodcock et al., 2009) and will only be summarized here, as our intent is to detail implementation rather than model development and underlying mathematics. The current version of ITHIM being used in the US is constructed as a multi-spreadsheet workbook in a commonly available spreadsheet application. This allows ITHIM to be run on most computers without additional software purchases.

ITHIM estimates the hypothetical health impacts of shifting travel patterns (e.g. distance and mode of travel) within a given population, assuming no time lag for behavior change or health impacts. Given these assumptions, the purpose of ITHIM is to estimate the magnitude and direction of potential net health impacts rather than to precisely forecast disease burdens. In the case of the NAMPO, these estimates were used to facilitate a broader discussion on the links between transportation and public health, and were not used to plan health services or budget for future disease burdens.

Within the model, health impacts are calculated through three exposure pathways: physical activity, air pollution, and traffic injuries and fatalities. For each pathway, ITHIM uses comparative risk assessment to predict changes in disease burden for a given change in exposure. Comparative risk assessment is derived from calculations of population attributable fraction (Bhopal, 2008), which estimates the burden of disease attributed to a specific exposure. The results from the pathways are combined and health outcomes are presented in four summary measures: total mortality (deaths per year), premature mortality (years of life lost), morbidity (years living with a disability), and combined morbidity and mortality (disability-adjusted life years [DALYs]), which are the sum of years of life lost and years living with a disability. ITHIM can also be used to estimate changes in CO2 emissions for a given change in travel patterns, but this functionality was not used in the greater Nashville area.

Cost Savings Estimation (2.2)

During implementation in California, two economic impact calculations were added to ITHIM that have not been previously published. The first method uses the value of a statistical life combined with ITHIM-predicted changes to mortality to estimate financial impact. The dollar value represented in the value of statistical life is the theoretical “amount that a group of people is willing to pay for fatal risk reduction in the expectation of saving one life” (Miller, 2000; Rogoff and Thomson, 2014; United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2015). The second method combines ITHIM-estimated changes in disease prevalence with published US estimates of the direct costs of treatment and indirect costs of lost worker productivity for a given illness or condition. Because the NAMPO used ITHIM results for public outreach messaging, the second, cost of illnesses method was used as this was judged more intuitive in early presentations of the data. In the Nashville implementation, this method also produced more conservative estimates than those based on the value of a statistical life. The conditions included in the cost of illness calculations and the relevant findings from the literature review are presented in Table 1. All values were inflation-adjusted to 2012 dollars (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2015). Nashville-specific cost estimates were calculated by multiplying the national estimate by the proportion of the US population that lives in greater Nashville (0.48%). This method is limited by assuming a similar demographic makeup and disease experience for Nashville and the US as a whole. The Nashville-estimated costs were then multiplied by the ITHIM-predicted change in disease burden to arrive at the estimated change in cost for each condition. Because this method does not account for delays between certain exposures and health outcomes (i.e. physical activity and prevention of cardiovascular diseases), the NAMPO presented the predicted financial impacts as illustrative examples that compared potential health effects to transportation spending using common units. These analyses fostered a larger discussion on transportation and health and were not used to plan healthcare resources or budgets.

Table 1.

Conditions included in the cost of illness calculations, their approximate annual costs to the United States, and the reference for each value.

| Condition | Base Year |

National Cost of Illness, Base Year ($, millions) |

Inflation factor |

National Cost of Illness, 2012 ($, millions) |

References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancers | ||||||

| Breast | 2010 | 27,379 | 1.05 | 28,748 | (Bradley et al., 2008; Mariotto et al., 2011) |

|

| Colorectal | 2010 | 26,942 | 1.05 | 28,289 | (Bradley et al., 2008; Mariotto et al., 2011) |

|

| Lung | 2010 | 51,073 | 1.05 | 53,627 | (Bradley et al., 2008; Mariotto et al., 2011) |

|

| Cardiovascular | ||||||

| Stroke | 2007 | 40,900 | 1.11 | 45,399 | (Roger et al., 2011) | |

| Heart disease | 2007 | 177,500 | 1.11 | 197,025 | (Roger et al., 2011) | |

| Respiratory | ||||||

| Asthma | 2007 | 56,000 | 1.11 | 62,160 | (Barnett and Nurmagambetov, 2011) |

|

| Mental Illness | ||||||

| Dementia | 2010 | 172,000 | 1.05 | 180,600 | (Wimo and Prince, 2010) |

|

| Depression | 2000 | 83,100 | 1.33 | 110,523 | (Greenberg et al., 2003) |

|

| Other | ||||||

| Diabetes | 2007 | 174,000 | 1.11 | 193,140 | (American Diabetes, 2008) |

|

| Traffic Injuries | 2005 | 99,319 | 1.18 | 117,196 | (Naumann et al., 2010) |

|

Calibration data sources (2.3)

For this implementation, ITHIM required 14 calibration data items covering underlying disease burdens, travel habits, physical activity participation, air pollution levels, and traffic injuries and fatalities. Multiple data sources were used; each is listed in Table 2 and explained in greater detail below. For all calibration data sources, 2012 values were preferred because this was the year of the most recent transportation planning study in greater Nashville.

Table 2.

ITHIM calibration data needs and sources for the NAMPO

| Source | Calibration Data Item | Units | Strata |

|---|---|---|---|

| Middle TN Transportation and Health Study1 |

Per capita mean daily travel distance | Miles/person/day | Travel mode2 |

| Per capita mean daily travel time | Min/person/day | Travel mode | |

| Ratio: per capita mean daily active transportation time (reference group: females aged 15–29 years) |

Dimensionless | Walk, bike, age3, sex | |

| Standard deviation of mean daily active transportation time | Min/person/day | None | |

| Walking speed | Miles/hour | None | |

| Ratio of daily per capita bicycling time to walking time | Dimensionless | Bicycle : walk | |

| Personal auto travel distance and time | Miles and hours/day | Driver, passenger | |

| Travel Demand Model |

Vehicle miles traveled (VMT) by facility type | Miles/day | Travel mode and road type4 |

| US Census | Distribution of population by age and gender | % | Age, sex |

| NHANES | Per capita weekly non-travel related physical activity | MET-hours/week | Median of quintile of walk + bicycle METs, by age and sex |

| TN Department of Health |

Age-sex specific ratio of disease-specific mortality rate between Nashville metro and USA. |

Dimensionless | Disease group5, age, sex |

| Proportion of colon cancers from all colorectal cancers | Dimensionless | None | |

| TN Department of Safety |

Serious and fatal injuries between a striking vehicle and a victim vehicle in road traffic collisions |

Injuries | Severity, striking mode X victim mode, road type |

| TN Department of Environment and Conservation |

Emissions of PM2.5 attributable to light-duty vehicles | Tons/day | None |

The Middle Tennessee Transportation and Health Study was the NAMPOs transportation planning study in 2012

Travel modes: Auto driver, auto passenger, motorcycle, bus, train, truck, walk, bike

Age groups: 0–4, 5–14, 15–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80+

Road types: local, arterial, highway

See Table 3

TN: Tennessee

NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

The Middle Tennessee Transportation and Health Study (MTTHS) was the NAMPO’s regional household travel survey from 2012 (n=5,164 households and 11,114 individuals) and provided seven of 14 calibration data items. Details of the MTTHS are available on the NAMPO’s website (Lee et al., 2013). The MTTHS included a log on which respondents recorded the mode, purpose, start time, and end time of all trips in a 24-hour period on an assigned weekday throughout 5 months of 2012. For all trips (n=50,294), distance was estimated using Google Maps default routes. These data provided calibration information on the baseline travel habits of Nashville area residents, including travel that involved walking or bicycling. Information on vehicle miles traveled by roadway type (local, arterial, and highway) were sourced from the NAMPO’s travel demand models.

Two federal sources of data were used for calibration. First, the age and sex distribution of the population covered by the NAMPO was obtained from the 2010 decennial US Census. Second, reliable estimates of non-travel related physical activity participation (leisure-time, domestic, and occupational physical activity) were not available at the local or state level, so publicly available values for these activity domains from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012 were used (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Greater Nashville may deviate from national estimates, but sensitivity analyses suggested the effect would be small (see sections 2.5 and 3.3), and NHANES was the only available source with sufficient sample size to stratify by quintile of active transportation participation, sex, and age group.

Several branches of the TN state government also supplied important calibration data. These data were not publicly available, and required coordinating with personnel at the relevant state agencies. The TN Department of Health provided mortality data for all diseases included in the ITHIM calculations. The specific disease groups, including International Classification of Diseases, version 10 codes, are presented in Table 3. The most recent data were available for the years 2008–2010. A three-year average mortality rate, stratified by age group and sex, was calculated for each condition. The TN Department of Safety provided the 3-year count of serious and fatal injuries attributable to roadway crashes for 2010–2012. These counts were stratified by severity (serious and fatal), roadway type (local, arterial, and highway) and by the modes involved in the crash (opposing and victim vehicle). In situations where the opposing and victim vehicles were not delineated, the heavier vehicle was assumed to be the opposing vehicle. We also did not include bicycle versus pedestrian injuries and fatalities as these scenarios were not recorded in the available data sets. Finally, the TN Department of Environment and Conservation provided average annual particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers in diameter (PM2.5) concentrations and the estimated proportion of regional PM2.5 that is attributable to light-duty vehicles. The light-duty vehicle contribution was not part of the originally-specified ITHIM calibration data points, but was needed to replace a default equation that was used in a previous ITHIM implementation in the San Francisco Bay Area (Maizlish et al., 2013). For each scenario, the proportional change in light-duty vehicle miles traveled was calculated (VMT%) and the light-duty vehicle contribution to regional PM2.5 burden was multiplied by (1−[VMT%]) to arrive at the predicted light-duty vehicle contribution.

Table 3.

Diseases included in the ITHIM model and their respective ICD-10 codes used to obtain mortality statistics for calibration

| Condition | ICD-10 Code(s) |

|---|---|

| Cancers | |

| Breast | C50 |

| Colorectal | C18–C21 |

| Trachea, bronchus, and lung | C33–C34 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | |

| Hypertensive heart disease | I10–I13 |

| Ischemic heart disease | I20–I25 |

| Inflammatory heart disease | I30–I33, I38, I40, I42 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | I60–I69 |

| Alzheimer’s and other dementias | F01, F03, G30–G31 |

| Depression (Unipolar depressive disorders) | F32–F33 |

| Road traffic injuries | V01–V89, Y85 |

| Respiratory conditions | |

| Lower and upper respiratory infections1 | J00–J06, J10–J18, J20–J22 |

| COPD, asthma, other respiratory diseases | J30–J39, J40–J98 |

Reported separately for children < 5 years

COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Once all inputs were obtained and formatted for ITHIM, they were manually entered into the ITHIM calibration data spreadsheet page. Due to the large number of stratifications to the calibration data (e.g. by age, sex, and mode), the 14 items listed on Table 2 comprised a total of 884 individual values.

Scenario Development (2.4)

According to the calibration (baseline) data from the MTTHS, residents in greater Nashville performed an average of three minutes per day or 21 minutes per week of walking and bicycling for transportation comprised of 0.7 miles per week of walking (18.4 minutes), and 0.3 miles per week of bicycling (2.6 minutes). Note that walking and bicycling for transportation are not common behaviors in greater Nashville, and many residents report doing neither. The average values are often attributable to a few individuals performing far more than the population average. We present average values rather than medians because the medians would be 0 and therefore less informative. The NAMPO was interested in estimating the health impacts of increasing the average amount of walking and bicycling in the region, so three scenarios were developed with progressively higher average walking and bicycling participation, while holding total miles traveled by all modes constant (Table 4).

Table 4.

ITHIM scenario per capita average miles and minutes traveled per week and ITHIM results expressed as annual change in deaths and disability-adjusted life years: Nashville area Metropolitan Planning Organization.

| Baseline | Conservative | Moderate | Aggressive | Injury- neutral |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per capita miles per week | |||||

| Walk | 0.7 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 5.7 | 1.7 |

| Bike | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 | 1.3 |

| Car | 195.9 | 194.2 | 191.6 | 188.1 | 175.1 |

| Driver | 151.8 | 150.5 | 148.5 | 145.8 | 142.9 |

| Passenger | 44.1 | 43.7 | 43.1 | 42.3 | 32.2 |

| Total1 | 225.0 | 225.0 | 225.0 | 225.0 | 206.2 |

| Per capita minutes per week | |||||

| Walk | 18.4 | 37.8 | 82.2 | 126.7 | 37.8 |

| Bike | 2.6 | 8.0 | 12.0 | 24.0 | 10.4 |

| Car | 418.1 | 414.6 | 409.2 | 401.7 | 373.7 |

| Driver | 324.0 | 321.3 | 317.1 | 311.3 | 305.1 |

| Passenger | 94.1 | 93.3 | 92.1 | 90.4 | 68.6 |

| Total2 | 494.5 | 515.7 | 558.8 | 607.8 | 477.3 |

| Results-DALYs | |||||

| Chronic Diseases | -- | 1,124 | 2,793 | 4,375 | 1212 |

| Injuries / Fatalities | -- | −552 | −1,240 | −1,733 | 1 |

| Net Change | -- | 572 | 1,552 | 2,642 | 1213 |

| Results-Deaths | |||||

| Chronic Diseases | -- | 38 | 109 | 165 | 41 |

| Injuries / Fatalities | -- | −14 | −31 | −43 | −2 |

| Net Change | -- | 24 | 71 | 123 | 39 |

Totals include these constants (miles): bus: 7.2, rail: 0.3, motorcycle: 0.6, truck: 20.1

Totals include these constants (minutes): bus: 31.7, rail: 0.5, motorcycle: 1.3, truck: 22.0

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years

In the conservative scenario, we modeled the effects of increasing average per capita walking an additional 1.0 mile per week and bicycling an additional 0.7 mile per week, which increased the average total weekly time in active transportation to 45 minutes per person. This translated to an additional 3.5 minutes per day on average in active transportation, twice the baseline per capita average. In the moderate scenario, we modeled the effects of increasing walking an additional 3.0 miles per week and bicycling an additional 1.2 miles per week, which increased the average total weekly time in active transportation to 94 minutes per person. This translated to an additional 10.5 minutes per day on average in active transportation. The aggressive scenario was developed as a “best-case scenario” in which we modeled the health impacts that could be expected if the average resident of greater Nashville met the aerobic component of the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines through active transportation (150 minutes per week of at least moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity)(US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). This duration was attained by increasing the baseline average walking distance by 5.0 miles per week and bicycling distance by 2.7 miles per week. This translated to an additional 18.5 minutes per day on average in active transportation.

A final scenario was developed to determine the reduction in car travel that would be necessary to offset any additional injuries and fatalities incurred by increasing the average per capita weekly walking and bicycling by 1 mile each. We held the ratio of car driver to car passenger miles constant and iteratively reduced these values by 0.1 mile until the predicted DALYs were ≤ 0.

Sensitivity Analyses (2.5)

We were interested in knowing which calibration items were most influential to the predicted health outcomes. To determine this, we varied the values of each calibration item by +/− 10% and recorded the net change in predicted DALYs. We noted the calibration data points that changed the absolute value of net DALYs by at least +/− 3%.

Results (3.0)

Process Summary (3.1)

The calibration began in January 2014. When calibration data were received from partner organizations, the analyses and data formatting were done by one person working approximately half-time on this project. It is important to note that the effort was discontinuous as there were periods with no activity while partner organizations gathered the needed data or the primary analyst worked on other projects. The initial pilot ITHIM runs were performed in August 2014 but did not include calibration for nonfatal traffic injuries, which was done in December 2014. Scenario development occurred in January and February 2015, and sensitivity analyses began in May 2015.

Nashville Scenarios (3.2)

Under the conservative scenario, ITHIM predicted 38 deaths averted due to prevention of chronic disease and 14 traffic fatalities incurred for a net improvement of 24 deaths per year averted (Table 4). The net change represents a 0.4% decrease in all deaths attributable to the conditions considered in ITHIM. When expressed as DALYs, the pattern was similar, with a net improvement of 572 averted DALYs, again representing 0.4% of the underlying total for these conditions (Table 4). The three conditions with the largest change were injuries and fatalities (+6.8%), diabetes (−1.1%) and cardiovascular diseases (−1.0%). After applying the summary results to the cost estimates, approximately $10 million was predicted to be saved through decreased direct healthcare expenses and indirect productivity losses. It should be noted that in this and all other scenarios, the benefits attained through increased physical activity far outweigh the benefits attained from reduced air pollution (99.99% versus 0.01%, respectively).

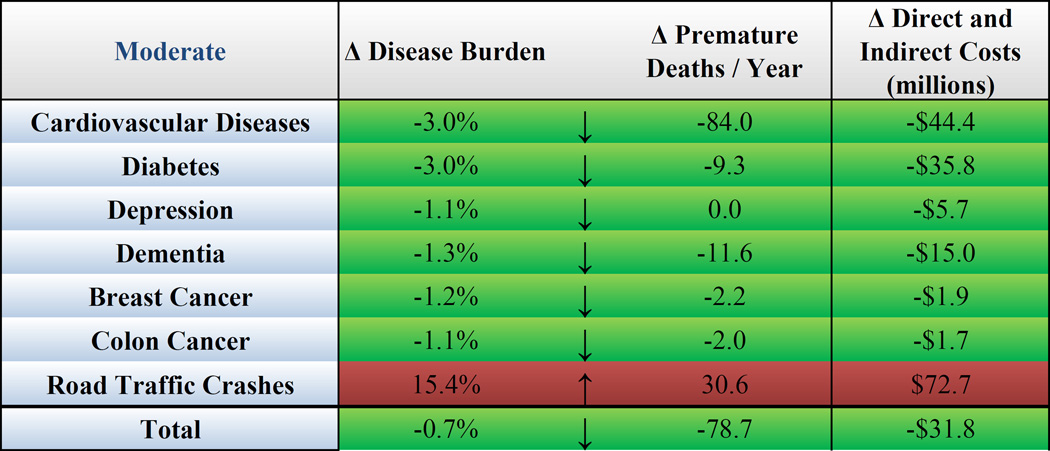

Under the moderate and aggressive scenarios, the predicted benefits continued to outweigh the predicted harms with a net decrease of 79 deaths per year (1.2% of total) and 1,552 averted DALYs (1.0% decrease in total DALYs). Injuries and fatalities (+15.4%), diabetes (−3.0%) and cardiovascular diseases (−3.0%) continued to be the conditions most heavily impacted. The cost estimates for the moderate scenario suggested that $32 million could be saved in direct and indirect costs. The aggressive scenario predicted a net decrease of 123 deaths per year (1.9% of total) and a net improvement of 2,642 averted DALYs (1.8% of total). Again, injuries and fatalities (21.5%), diabetes (−4.7%), and cardiovascular diseases (−4.6%) contributed the largest changes. The estimated cost savings of the aggressive scenario totaled $63 million in direct and indirect costs.

In the final scenario, after an increase in both walking and bicycling of 1.0 mile per person per week, the iterative reductions in car miles traveled suggested that an 11% decrease in car miles per person per week (175.1 versus 195.9 miles per week, Table 4) would offset incurred DALYs due to pedestrian and bicyclist injuries and fatalities. While the decrease in average car miles per person is substantial, the average commute distance in greater Nashville is 11 miles (Kneebone and Holmes, 2015); for the average commuter, this change could be achieved by telecommuting one day per week. The model suggested that 1,212 DALYs would be averted due to chronic disease prevention (primarily cardiovascular disease at −1.7% and diabetes at −2.0%) and 1 DALY would be averted due to reduced injuries and fatalities. The predicted change in deaths was slightly different in that 41 deaths would be averted due to chronic disease prevention, but 2 deaths would be incurred from fatal injuries. The difference in deaths versus DALYs in this scenario is attributable to different calculations for predicted non-fatal and fatal injuries; both DALY and death estimations include fatalities while only DALYs include non-fatal injuries. There is a large enough decrease in non-fatal injuries in this scenario to cause a net improvement in DALYs, but not deaths. The estimated direct and indirect cost savings under this scenario totaled approximately $46 million, placing it between the moderate and aggressive scenarios.

Sensitivity Analyses (3.3)

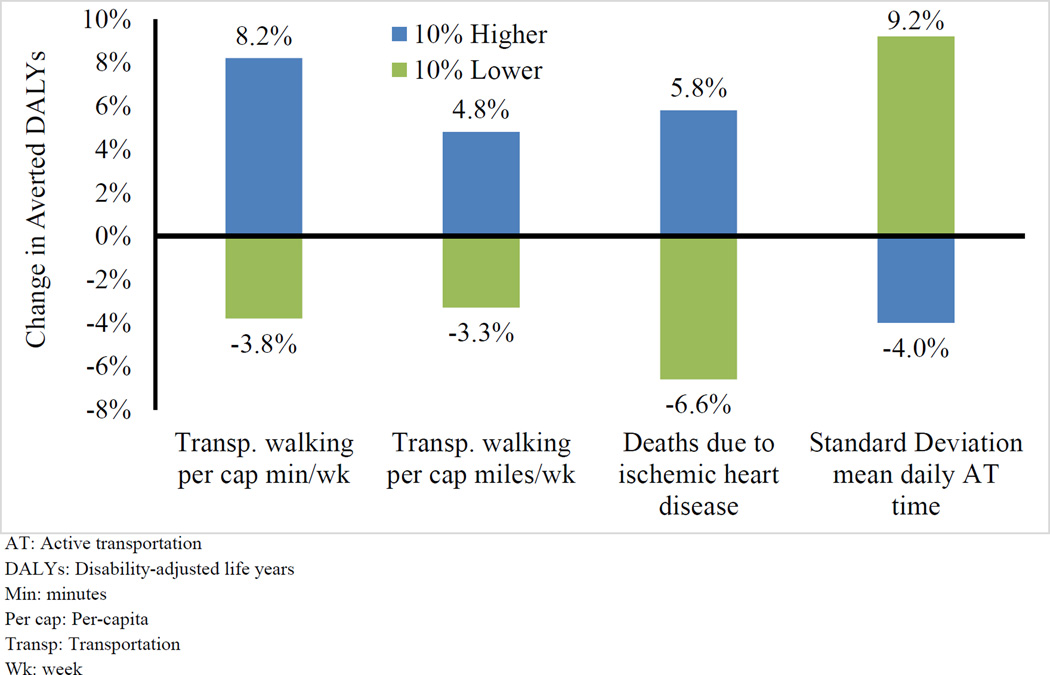

The sensitivity analyses were conducted under the conditions of the moderate scenario described previously (Table 4). The results of sensitivity analyses suggested that four calibration data items changed net results by ≥ 3% when their value was changed by +/− 10%: per capita mean daily transportation minutes and miles, mortality due to ischemic heart disease, and the standard deviation of mean daily active travel time (Figure 1). Of these, the largest change was a 9.2% increase in net averted DALYs caused by a 10% decrease in the standard deviation of mean daily active travel time. While not considered a regional calibration data item as described above, we found that a modifiable parameter included in ITHIM to approximate the “safety in numbers” effect (Jacobsen, 2003) in injury and fatality calculations was also impactful. This agrees with the findings of Maizlish, et al, and interested readers are directed there for a technical explanation (Maizlish et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Results of sensitivity analyses on the 14 ITHIM calibration data items for the Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization showing the four most influential calibration items

AT: Active transportation

DALYs: Disability-adjusted life years

Min: minutes

Per cap: Per-capita

Transp: Transportation

Wk: week

Discussion (4.0)

Implementation of ITHIM in greater Nashville was a multistep, collaborative process that yielded valuable insight into the relation between transportation mode choices and health. Input was needed from local, state, and federal sources, including the NAMPO, TN Department of Health, TN Department of Safety, TN Department of Environment and Conservation, US Census Bureau, and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The findings from this effort suggested that if health impacts from altered transportation patterns occurred without delay, the benefits from chronic disease prevention might be greater than the incurred harms of increased traffic injuries and fatalities, and that incurred harms might be ameliorated by reducing car travel. The NAMPO is actively using these results to further support their efforts around active transportation initiatives.

Data considerations (4.1)

The strength of ITHIM is the comprehensiveness with which it evaluates the health impacts of changing transportation patterns. By considering transportation and non-transportation physical activity, mode- and roadway-specific injuries and fatalities, and regional PM2.5 levels, and combining these with age- and sex-specific disease burdens, ITHIM is able to estimate both potential benefits and harms of different transportation mode shifts. Notably, the main factor that limits ITHIM’s widespread use is related to this strength: the need for extensive calibration data. Acquiring, cleaning, formatting, and entering calibration data into the model requires considerable statistical analyses and data management skills. Many jurisdictions, especially smaller cities, might not have reliable estimates for several calibration data items, or might lack the population size needed to attain reliable estimates. Also, because data are needed from collaborating organizations, the speed at which those data are made available could be a rate-limiting step in preparing ITHIM for use. Before beginning an ITHIM implementation, a jurisdiction might benefit from meeting with collaborators to discuss data needs, such as date ranges, formats, and schedule for data delivery, in order to prioritize analyses and streamline the calibration process. Other models, including the Health Economic Assessment Tool from the World Health Organization (World Health Organization, 2014), require fewer inputs and are simpler to implement, but are less comprehensive than ITHIM. This option may be preferable for those needing rapid estimates of health impact.

The calibration process required several important decisions on data usage. First, ITHIM was developed in part to model the health co-benefits of reducing greenhouse gas emissions through altered transportation patterns. The NAMPO decided not to use the greenhouse gas functionality in the model as this was not a policy priority in the greater Nashville region. Second, previous implementations have used a linear equation to model the association between vehicle miles traveled and PM2.5 levels (Maizlish et al., 2013). Such equations can be obtained from travel demand and air shed models. For the NAMPO, this approach was not possible because of time and staffing constraints. Instead, we modeled proportional reductions to the fraction of regional PM2.5 that is attributed to light-duty vehicles. This approach yielded similar results to those presented by Maizlish et al (2013) in that the air pollution benefits were miniscule in comparison to the benefits of increased physical activity. Future ITHIM users might similarly consider alternative data sources when the exact data are unavailable.

Data presentation and use (4.2)

The NAMPO used ITHIM output for messaging that supported their walking, biking, and transit initiatives. In particular, information on potential cost savings and disease-specific effects (Figure 2) were noted as important by local stakeholders and the NAMPO Executive Board, which is made up of elected officials from the NAMPO jurisdiction, area transit agencies, the TN Department of Transportation, and the Federal Highway Administration. Recipients of these results tended to prefer easy-to-understand values like deaths averted (as in Table 4) and % reductions in disease burdens over DALYs, which might be confusing to those outside the public health and safety fields.

Figure 2.

Disease-specific results for the moderate scenario showing predicted changes in disease burdens as deaths per year and direct and indirect costs

When presenting ITHIM results, several questions arose repeatedly from various audiences. First and foremost, many stakeholders expressed concern over the predicted increased burden of injuries and fatalities (e.g. +15.4% in the moderate scenario). Our decision to hold constant total miles traveled under the conservative, moderate, and aggressive scenarios contributed to this burden. We assumed that every mile of additional walking and bicycling would replace one mile of car travel (a 1:1 substitution). If people choose destinations that are closer when walking or bicycling versus driving, this would result in a proportionally larger decrease in car miles traveled. In post-hoc alternative scenarios, increasing to a 1:1.5 mile substitution reduced the incurred DALYs under the moderate scenario from 1,240 to 1,175. As evidenced by our injury-neutral scenario, further reductions in car travel might remove this burden entirely. Additionally, the “safety in numbers” exponent in the ITHIM injury predictions might not fully or accurately account for changes in safety that would result from built environment changes that support walking and bicycling, and this was shown to be an influential parameter in sensitivity analyses. Future research might shed light on the causes of the safety in numbers phenomenon (Jacobsen et al., 2015), allowing better representation of this effect in modeling efforts.

Another area of concern among audiences was the timing of ITHIM predicted effects, as mentioned in sections 2.1 and 2.2. Some protective effects of physical activity and reduced air pollution modeled in ITHIM require years or decades to accrue, whereas traffic injuries and fatalities have a more immediate impact. Also, transportation behavior change resulting from new or improved transportation infrastructure could require months or years to fully take hold, and some physically active forms of transportation could simply replace other active behaviors such as leisure time exercise. As implemented in Nashville, ITHIM is modeling the predicted effects of immediately changing the behavior of the population as it existed at baseline (2012), and assuming all effects begin to accrue immediately, continue for one year, and do not displace other active behaviors. It was helpful to repeatedly acknowledge the timing disconnect and stress the hypothetical nature of these calculations.

Finally, the sectors impacted by potential cost savings were noted on occasion. The predicted savings in our models would be primarily realized by private individuals and insurers (direct healthcare costs) and employers (increased productivity and some direct costs). Conversely, expenditures to help increase walking and bicycling would likely be borne by the transportation sector. This is a valid point for public outreach, and may be partially offset by the reduced cost to construct and maintain pedestrian and bicyclist transportation infrastructure compared to that for only automobiles.

The importance of sensitivity analyses (4.3)

The sensitivity analyses produced some important insights for this, and perhaps other ITHIM implementations. First, care should be taken with walking data. In Nashville and in many US cities (McKenzie, 2014), walking was far more common than bicycling at baseline, meaning it was the primary determinant of time spent in active transportation, and we maintained the walking to bicycling ratio in 3 of our 4 scenarios. ITHIM uses time spent in active transportation combined with its standard deviation (another influential data item), to model the shape of the distribution of physical activity in the population, giving these items a sizeable impact. Second, we were concerned about the validity of using national estimates from NHANES to represent the non-transportation physical activity in greater Nashville. Sensitivity analyses showed that these values were not overly influential: a 10% change in either direction altered DALY estimates less than one percent. Finally, sensitivity analyses were useful for identifying errors with the calibration data. During this process, we identified erroneous mortality statistics and an omitted calculation estimating the variability of daily active transportation time. The act of manually changing calibration values allowed recognition and correction of these issues.

Concluding remarks (4.4)

Future implementations of ITHIM might not be as complicated as the Nashville experience. The ITHIM model developers have begun preliminary work on a new version of ITHIM that uses open-source statistical software and, potentially, different calibration data sources and formats (Woodcock et al., 2015). Additionally, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is currently working on a national calibration of the current ITHIM version that might yield insights into scaling to smaller geographic regions such as states and cities. These efforts could considerably reduce the effort of implementing ITHIM in years to come.

Implementing ITHIM in Nashville was one of several steps that the NAMPO has taken to improve population health through transportation planning. Building upon citizen input and health and transportation survey data, the ITHIM results provide context for the overarching health and transportation goals of the greater Nashville region. NAMPO's primary purpose in running ITHIM was to help quantify for decision makers and the public the potential impact of active transportation on health outcomes. ITHIM outputs were well-received, the results are referenced in the NAMPO 2040 Regional Transportation Plan in which active transportation projects were substantially increased.

Further efforts to realize these potential health benefits could include targeted selection of projects that encourage the desired behavior changes. Health and transportation scenario planning tools and latent demand models that provide information at small geographic scales could complement ITHIM (Calthorpe Associates, 2012, Ulmer, et al., 2014). Whereas ITHIM estimates the broad health changes that could occur with a change in transportation behaviors, these complementary methods might be able to identify built environment projects and specific locations that are most likely to produce the modeled behaviors.

In conclusion, ITHIM has provided important insights into the links between transportation and health in greater Nashville. The model suggests that even modest increases in walking and bicycling could have meaningful impacts on health and financial outcomes, though cautious interpretation of results is warranted given the assumptions of the model. Implementing ITHIM was a collaborative effort spanning nearly a year of intermittent work and requiring considerable data analysis and management skills. Other jurisdictions might benefit by evaluating the feasibility of completion before investing significant resources in an ITHIM implementation.

Acknowledgments

No external funding was used for this work. This work does not present the official policy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

References

- Bhopal R. Concepts of Epidemiology. Second. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caizzo F, Ashok A, Waitz I, Yim S, Barrett S. Air pollution and early deaths in the United States. Part I: Quantifying the impact of major sectors in 2005. Atmospheric Environment. 2013;79:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Calthorpe Associates. Urban Footprint Technical Summary. 2012 http://www.scag.ca.gov/Documents/UrbanFootprintTechnicalSummary.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Recommendations for Improving Health through Transportation Policy. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/transportation/docs/final-cdc-transportation-recommendations-4-28-2010.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: 2013. NHANES 2011–2012 Questionnaire Data. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/DataPage.aspx?Component=Questionnaire&CycleBeginYear=2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iroz-Elardo N, Hamberg A, Main E, Haggerty B, Early-Alberts J, Cude C. In: Climate Smart Strategy Health Impact Assessment. Oregon Health Authority, editor. Portland, OR: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PL. Safety in numbers: more walkers and bicyclists, safer walking and bicycling. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention. 2003;9:205–209. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.3.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PL, Ragland DR, Komanoff C. Safety in Numbers for walkers and bicyclists: exploring the mechanisms. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention. 2015;21:217–220. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneebone E, Holmes N. The Brookings Institute. Washington, DC: 2015. The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America. http:// http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports2/2015/03/24-people-jobs-distance-metropolitan-areas-kneebone-holmes. [Google Scholar]

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380:219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Chan J, Fucci A, Jaworski D, Kline J, McCloskey S, Wilson L, Fussell R. Nashville, TN: Nashville Area Metropolitan Planning Organization; 2013. Middle Tennessee Transportation and Health Study Final Report. http://www.nashvillempo.org/docs/research/Nashville_Final_Report_062513.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Maizlish N, Woodcock J, Co S, Ostro B, Fanai A, Fairley D. Health cobenefits and transportation-related reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in the San Francisco Bay area. American journal of public health. 2013;103:703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie B. Modes less traveled - Bicycling and walking to work in the United States: 2008–2012. In: US Department of Commerce, editor. Washington, DC: 2014. https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/ acs-25.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR. Variations between countries in values of statistical life. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy. 2000;34:169–188. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff P, Thomson K. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation; 2014. Guidance on Treatment of the Economic Value of a Statistical Life (VSL) in U.S. Department of Transportation Analyses - 2014 Adjustment. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer J, Chapman J, Kershaw S, Campbell M, Frank L. Application of an evidence-based tool to evaluate health impacts of changes to the built environment. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2014;106:eS26–eS32. doi: 10.17269/cjph.106.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Transportation; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Washington, D.C.: 2015. Fatality analysis reporting system (FARS) encyclopedia. http://www-fars.nhtsa.dot.gov/Main/index.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Washington, DC: 2015. Frequently Asked Questions on Mortality Risk Valuation. http://yosemite.epa.gov/EE%5Cepa%5Ceed.nsf/webpages/MortalityRiskValuation.html#whatvalue. [Google Scholar]

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Washington, DC: 2015. CPI Inflation Calculator. http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. http://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock J, Edwards P, Tonne C, et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: urban land transport. Lancet. 2009;374:1930–1943. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock J, Tainio M, Lovelace R. Washington, DC: 2015. Cycling health and climate, Moving Active Transportation to Higher Ground: Opportunities for Accelerating the Assessment of Health Impacts; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. HEAT - Health Economic Assessment Tool. http://www.heatwalkingcycling.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Yoon PW, Bastian B, Anderson RN, Collins JL, Jaffe HW Centers for Disease, C., Prevention. Potentially preventable deaths from the five leading causes of death--United States, 2008–2010. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2014;63:369–374. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]