Abstract

This study qualitatively examined the experiences of Mexican-origin women caring for elderly family members in order to identify aspects of familism in their caregiving situations. Data were collected from onetime interviews with 44 caregivers living in the greater East Los Angeles area. Kinscripts guided the framing of familism in this study. Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach. Caregivers’ descriptions of the Mexican family reflected an idealized view of familism. Caregivers reported a lack of support from others and relying for support on fewer family members than were potentially available to them. Findings suggest that the construct of familism has evolved from its long-standing portrayals in the literature. More research is needed to reexamine familism as a theoretical perspective to explain how Mexican-origin families negotiate and construct elder care over the family life course.

Keywords: Aging, caregiving, culture, family relations, Hispanic Americans, qualitative research

Background

Familism is an enduring principle and structure of the family in Latino cultures. Although there is not a universal definition of familism in the literature, research has described familism as a multidimensional construct composed of core values such as strong family identification, attachment, mutual support, family obligation, and familial interconnectedness (Almeida, Molnar, Kawachi, & Subramanian, 2009; Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003; Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, Marin, & Perez-Stable, 1987). Familism is embedded in an extended-family network that includes family members such as aunts, uncles, cousins, and in-laws (Keefe, 1984; Sabogal et al., 1987). Researchers have considered familism as a key factor to explain interrelations in this extended network (John, Resendiz, & De Vargas, 1997; Losada et al., 2010; Scharlach et al., 2006; Shurgot & Knight, 2005) and to explain family roles and obligations for such responsibilities as child rearing, godparenting, surrogate grandparenting, and—to a lesser extent—elder caregiving (Delgado, 2007; Gonzalez, Germán, & Fabrett, 2012; John et al., 1997; Losada et al., 2010; Scharlach et al., 2006; Shurgot & Knight, 2005).

The corpus of the family literature has focused on familism as it relates to child, adolescent, and youth development and/or to the parent–child relationship (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006; Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009; Morcillo et al., 2011; Santisteban, Coatsworth, Briones, Kurtines, & Szapocznik, 2012). This concerted attention in the family research arena has obviated the critical function of familism in elder care arrangements and caregiver–elder relations. Moreover, the existing research on the perceived value of familism in elder caregiving has had mixed results. Some findings show that the belief in familism conveys a perceived availability of support and caregiver satisfaction in their work. For instance, Losada et al. (2006) found that higher scores on familism scales were inversely correlated with lower scores on caregiving burden, but Crist et al. (2009) found no statistically significant correlation between the two. One qualitative study of Mexican American caregivers found that familism was an important factor in their caregiving decision making and social support systems (John et al., 1997). Two other studies of Latino caregivers found that familism was a motivation for providing care and was associated with perceived positive caregiving experiences (Scharlach et al., 2006) and the acceptance and fulfillment of the caregiving role without complaint (Magana, Schwartz, Rubert, & Szapocznik, 2006). Other studies, however, found familism to be associated with caregiver distress (Youn, Knight, Jeong, & Benton, 1999) and lower levels of perceived positive support (Shurgot & Knight, 2005). Additionally, other research reported familism as sociocultural beliefs of caregiving that predisposed caregivers to higher levels of depression and perceived stress (Rozario & DeRienzis, 2008).

These mixed results suggest the need to reexamine familism, specifically its underlying premises, as a guiding theoretical construct in Latino family caregiving research. To move this effort forward, we conducted a qualitative analysis to explore the lived experiences of caregiving women in the context of their family circumstances. This study was part of a larger study whose overall objective was to explore how women of Mexican origin conceptualized caregiving as a construct in terms of cultural beliefs, social norms, role functioning, and familial obligations. The aims of this article are to describe women’s views of the caregiver role and the involvement of other family members in the caregiving process from a familism lens, which presumes a close-knit family orientation.

Social Organization, Family Roles, and Social Role Expectations

Gender role differentiation and social role functioning are important to the social organization of Latino cultures and are embedded within the notion of familism (Staton, 1972). In the case of the traditional Mexican family, machismo and marianismo are roles occupied by the father and mother, respectively (Gutmann, 1997; Hubbell, 1993). Machismo is the concept of masculinity or manliness in Mexican culture, which includes characteristics such as male dominance, aggressive sexuality, bravery, and protection of women and children (Falicov, 2010; Sobralske, 2006; Torres, Solberg, & Carlstrom, 2002). According to Falicov (2010), a prototypical macho is “one who can drink the most, sire the most sons, defend himself the most, dominate his wife, and command the absolute respect of his children” (p. 309). As the macho, the traditional Mexican father is considered the head of the household, breadwinner, and major decision maker in the family (Olson, 1977; Staton, 1972).

Marianismo is the traditional role of the mother in the Mexican family. The socialization of the female marianismo role starts in early childhood and is particularly influential in women’s expected behaviors of femininity, submission, weakness, reservation, and virginity (Bridges, 1980; Finkler, 1994; García & de Oliveira, 1997; LeVine, Sunderland Correa, & Tapia Uribe, 1986; Nader, 1986; Olson, 1977; Peñalosa, 1968). As the mariana, the mother is expected to be completely submissive to her husband, acknowledge his authority, and perform self-sacrificing behaviors to benefit her family (García & de Oliveira, 1997; Hubbell, 1993; Peñalosa, 1968). This traditional female gender role is based on the emulation of the Virgin Mary in the Catholic religion and has been referred to as la madre abnegada (Hubbell, 1993), or “self-sacrificing mother.” Thus, the ideal Mexican mother is one who fulfills familism ideals by sacrificing her own needs and happiness for the sake of her family (Finkler, 1994; Hubbell, 1993), or subjugating the self for family (Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003). However, while Mexican social roles have a history of rich description (Bridges, 1980), machismo and marianismo are not empirically tested concepts. Moreover, the abundant literature on caregiving stress, burden, and ambivalence belies this portrayal of women, even in research with Latino samples where the findings are less clear.

The Cultural Context of Care in Latino Families

More than 25 years ago, Wallace and Facio (1987) pointed out the gap between the views and behaviors of caregiving in Latino populations. They argued that research on Latino aging has used familism as the main construct underlying the relationship of elders to their families, thereby shaping the study of Latino aging in a narrow frame. They further argued that by studying Latino aging in the context of familism as it has been conceptualized, researchers have often reached three conclusions: “First, the extended family is described as offering high status and distinct roles to older family members. Second, the extended family provides the aged Chicano and Latino with social support. Third, familism perpetuates a traditional gender hierarchy that continues into old age” (Wallace & Facio, 1987, p. 339). The authors argued that conceptualizing Latino aging only as a family issue has limited its theoretical and empirical importance. They further emphasized that the supportive nature of family for Latino elders differs depending on how familism is constructed and on the changing structural conditions that extend beyond the family.

Gelman’s (2014) work with Latino caregivers for individuals with Alzheimer’s provides support for Wallace and Facio’s (1987) critique of familism. Gelman (2014) found that beliefs about familism and its influence on elder caregiving were not consistent across caregivers’ personal narratives. Some caregivers viewed familism as a way of facilitating traditional caregiving; however, other caregivers rejected familism as irrelevant to their own caregiving experiences or felt conflicted between familistic principles and their own negative feelings about caregiving.

Other theoretical perspectives have been offered to frame the cultural context of care in Latino families. Rochelle (1997) criticized the culture of poverty and strength resiliency frameworks as flawed for overgeneralizing conditions of the family that are not substantiated or for perpetuating stereotypes about the Latino family. Rochelle argued that these theoretical perspectives fall short in explaining whether the structure and practice of caregiving in Latino and other populations reflect a cultural condition, economic need, or other structural conditions.

Kinscripts

The critiques by Wallace and Facio (1987) and Rochelle (1997) reveal gaps in theorizing about the structure and dynamics of elder caregiving in Latino families. In our study, we used a kinscripts framework (Stack & Burton, 1993) to guide our framing of familism and to address the lack of theory in caregiving research on ethnic minority groups (Dilworth-Anderson, Williams, & Gibson, 2002).

Kinscripts originated from studies on kinship and from the life course perspective to explain the dynamics of family life in low-income, multigenerational African American families (Stack & Burton, 1993). Kinscripts is similar to familism in that kinscripts examines family life and role functioning on the basis of culturally constructed conditions and shared beliefs. Kinscripts comprises three culturally defined domains—kin-work, kin-time, and kin-scription—that resemble important facets of familism, such as extended family orientation, familial obligation, mutual support, and subjugation of self. Kin-work refers to the collective labor that occurs within and across households in family-centered networks (Stack & Burton, 1993). This collective effort is generated and maintained by expectations, shared beliefs, and values of members in the family networks. Kin-work comprises reproduction, intergenerational care, economic survival, migration, and social support; men, women, and children share in kin-work as prescribed by the family’s circumstances (Stack & Burton, 1993). Kin-time refers to the shared understanding of when and in what sequence labor and transitions unfold in the family network. As a temporal script based on the family’s cultural norms and behaviors, kin-time reflects cooperative action among members to progress through the family’s life course. Kin-scription is the recruitment of individuals to do family labor (Roy & Burton, 2007). Recruitment involves negotiation and power dynamics between members of the network in order to produce and maintain kin-time and kin-work.

Unlike familism, the domains of kinscripts are derived from the unique circumstances of the family network and thus adjust to different types of networks and life circumstances. This flexibility is an important enhancement to familism for two reasons. First, Latino families are not homogeneous, and some may be multihousehold, multigenerational, and/or multilingual, while others are not. Second, differences may exist between fulfillment of family role obligations and individuals’ self-subjugation in the interest of family. As Wallace and Facio (1987) pointed out, familism as currently conceptualized in the literature does not allow for these kinds of differences. For example, family obligation in familism is expected of everyone in the family (Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010). However, kinscripts allows for variations in caregiving contexts that lead to the unequal self-subjugation across family members, and it is thus a good framework within in which to theorize about familism in Latino families.

Method

Qualitative interviews were used to investigate the lived experiences of female Mexican-origin caregivers. This method was selected because it allows for an in-depth exploration of caregiving (Abel, 1991) and the examination of caregiving concepts that are not detected in typical survey approaches, such as the emotional and the symbolic meanings of filial obligation (Blieszner & Hamon, 1992). Despite the growing recognition that qualitative methods can be useful for expanding the construct of familism beyond the ideal, few studies have actually focused on the embeddedness of familism in the elder caregiving experiences of Latino families (Gelman, 2014), including in the Mexican-origin population.

Through the use of semistructured interviews and grounded theory analytic methods, we sought to understand caregivers’ meanings, beliefs, and experiences of elder caregiving within their socially constructed realities (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Hendricks, 1996). We were particularly interested in how familism played out in their kinscripts of eldercare.

Study Site

The site for the present study was East Los Angeles, California (East LA), an unincorporated area of Los Angeles County geographically located east of Downtown Los Angeles. We chose East LA as the study site because it has a high density of Mexican-origin Latinos in a relatively compact area. East LA has the highest percentage of Latinos (97%) among the top ten places in the United States with a population of 100,000 or more (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011). Ninety-one percent of all Latino residents in East LA are of Mexican descent (American Community Survey, 2011a). Forty-three percent of East LA’s population is foreign born, and 88% speak a language other than English at home (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), compared to 36% and 75%, respectively, of the total U.S. Latino population (American Community Survey, 2011b, 2011c). The percentage of persons in East Los Angeles living below the federal poverty level (27%) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010) is slightly higher than all unrelated Latino individuals nationally (23%) (American Community Survey, 2011d).

Sample Recruitment

We recruited participants in three phases from March 2006 to August 2012, although most interviews occurred between 2006 and 2007. Women who met the following criteria at the time of interview were eligible to participate in the study: (a) at least 18 years old, (b) of Mexican descent, (c) a resident of the greater East Los Angeles area, and (d) responsible for the day-today care of a dependent elderly relative. An elderly family member was defined as a person at least 60 years old related through blood or marriage. A dependent was defined as a person who needed assistance with one or more of the activities of daily living (ADLs) (Katz, 1983) or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Both ADLs and IADLs measure the extent to which care receivers cannot perform self-care tasks, and they are used to assess levels of caregiving need (National Center for Health Statistics, 2006). ADLs usually refer to basic functions such as feeding, bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and personal hygiene, and IADLs usually refer to more complex activities such as transportation, cooking, grocery shopping, housework, and financial management. We made an exception to the age requirement three times when care recipients were not yet 60 years of age but their caregivers identified them as “old.” We developed broad eligibility criteria because we were interested in examining a range of caregiving experiences.

We focused on identifying and enrolling caregivers of community-dwelling, noninstitutionalized elders. Previous studies have highlighted the challenges of recruiting caregivers into research (Buss et al., 2008; Dilworth-Anderson & Williams, 2004; Gallagher-Thompson, Solano, Coon, & Areán, 2003). We expected our study to be no different because Latino caregivers tend to use formal services less or be less aware of available services than other caregiver populations (Crist et al., 2009; Mausbach et al., 2004), and caregivers in general may not readily identify themselves in this role (Kutner, 2001; O’Connor, 2007). We expected the inclusion of Spanish-speaking caregivers in the research to further compound our recruitment challenges. Thus, we spent a considerable amount of time establishing a presence in the community. During the two-year period when the majority of interviews were conducted, we documented more than 63 visits to the community for 318 hours, not including the time spent conducting interviews (Mendez-Luck et al., 2011). We recruited women using multiple approaches, which ranged from collaborating with community-based organizations on targeted recruitment events to independent investigator-initiated efforts, such as face-to-face contact with community residents on street corners and bus stops; attending public events such as health fairs and handing out flyers and/or staffing information tables; and posting flyers at local markets, bakeries, and laundromats. We also received permission to post announcements in the weekly bulletin at local Catholic parishes and to post flyers at churches, as well as to include flyers in the bulletin at one parish. Our community partners were mostly not-for-profit human services organizations that served senior citizens, caregivers, or low-income Latino families in the greater East Los Angeles area. Our efforts in establishing relationships in the community are documented elsewhere (Mendez-Luck et al., 2011).

We also used snowball sampling to recruit participants into the study. This technique is especially useful for finding subjects with similar characteristics (Bernard, 1995), such as being a caregiver, and has been shown to be particularly effective for locating community-dwelling caregivers and elders who may not access social or medical services (Mendez-Luck et al., 2011; Rodriguez, Rodriguez, & Davis, 2006). After a participant was successfully enrolled into the study, we asked whether she knew of another caregiver who might be interested in the study. Former participants and ineligible but interested women aided in recruitment through word of mouth to their friends and family.

Last, we used purposive sampling to find study participants who represented a range of caregiving situations to explore relevant themes that emerged from previous interviews. Specifically, we sought out individuals to increase variation in the sample to pursue theoretical leads in the data to achieve theoretical saturation (Roy, Zvonkovic, Goldberg, Sharp, & LaRossa, 2015).

Sample

A total of 44 Mexican-origin women enrolled in the study from our recruitment efforts. Eighteen women were born in the United States, and 26 were born in Mexico. All participants born in the United States were interviewed in English, and all but one of the participants born in Mexico were interviewed in Spanish. The study sample tended to be longtime residents of their respective neighborhoods, with 30 participants living in East Los Angeles and 14 participants residing in nearby communities. Mexican American participants reported having lived in their neighborhoods for an average of 36.5 years, with a broad range of 1 to 68 years. Mexico-born participants reported having lived at their present locations for 22 years on average, with a range of 1.7 to 45 years. The mean age of participants was 52.6 years, with a range of 23 to 89 years. The participants’ educational levels ranged broadly from no formal education to 21 years (graduate school), with an average of 10 years. However, 34% of participants had less than a ninth-grade education. Eighty-two percent of participants did not work outside the home. The average monthly income for caregivers’ households was $2,017, with a broad range of $750 to $5,400. However, half of participants had monthly household incomes of $1,630 or less. We considered household income as the pooled monies of family members, such as caregivers and their spouses, care receivers and their spouses, and other related persons living in the household. However, nine caregivers lived in households with other family members who did not contribute to the household’s income as a whole. Thus, the average number of persons supported on the pooled monthly income was three, whereas the average size of households was four persons. The size of the household and the number of persons supported on the pooled incomes had the same range of one to 14 persons.

The majority of participants (32) gave care to nonspousal relatives (Table 1). The mean age of care recipients was 73.4 years, with a range from 55 to 93 years. The mean number of years spent caregiving was 8.3, with a broad range from eight months to 62 years, reflecting a mix of short- and long-term caregiving situations. Immigrant caregivers were younger, cared for younger care recipients, were less educated, and had lower incomes than the U.S.-born caregivers. A greater proportion of Mexico-born participants, compared to Mexican American participants, shared households with their elderly care recipients (85% vs. 72%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Respondents and Care Recipients

| Characteristic | n | % | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Mean caregiver age (in years) | — | — | 52.6 | 17.8 |

|

| ||||

| Mean care recipient age (in years) | — | — | 73.4 | 10.2 |

|

| ||||

| Mean years of caregivers’ education | — | — | 10.0 | 4.2 |

|

| ||||

| Mean length of caregiving (in years) | — | — | 8.3 | 11.7 |

|

| ||||

| Mean monthly family income | — | — | $2,017 | 1194.4 |

|

| ||||

| Number of persons supported on income | — | — | 3.0 | 2.6 |

|

| ||||

| Mean years of marriage for spousal caregivers | — | — | ||

|

| ||||

| Number of members in household | — | — | 4.0 | 2.7 |

|

| ||||

| Caregiver employment status Employed |

8 | 18.2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Marital status of nonspousal caregivers | — | — | ||

| Married | 12 | 37.5 | ||

| Never married | 9 | 28.1 | ||

| Divorced or separated | 5 | 15.6 | ||

| Widowed | 3 | 9.4 | ||

| Other | 3 | 9.4 | ||

|

| ||||

| Caregiver & care receiver share household | 35 | 79.5 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Care receiver–caregiver relationship | — | — | ||

| Husband | 12 | 27.3 | ||

| Parents | 23 | 52.0 | ||

| Mother-in-law | 2 | 4.5 | ||

| Other relatives | 7 | 15.9 | ||

|

| ||||

| Number of family members in household | - | - | ||

| One | 3 | 6.8% | ||

| Two | 13 | 29.5% | ||

| Three | 10 | 22.7% | ||

| Four or more | 18 | 40.9% | ||

Note. N = 44.

Data Collection

We obtained informed consent from participants using procedures approved by the UCLA and Oregon State University institutional review boards. Data were collected through semistructured interviews using an interview guide that had been previously used in another caregiving study conducted by the primary author on a sample of female Mexican, Spanish-speaking caregivers (Mendez-Luck, Kennedy, & Wallace, 2008, 2009). The question guide covered four topic areas: (a) story of becoming a caregiver, (b) forms of assistance and contexts of caregiving, (c) social and cultural beliefs about aging, and (d) beliefs about the caregiver role. We specifically asked participants a series of open-ended questions about their families, the care they provided to care receivers, and their caregiving situations. We also asked each participant about the assistance her family members provided either directly or indirectly to the care receiver. We used probing questions to elicit a richer set of responses for each topic.

The interviews were conducted by the principal investigator or a native-speaking research assistant trained by the principal investigator in field research and in-depth interviewing techniques. The interviews took place in the participant’s home or a location of her choice, such as a local community center, coffee shop, or church. All interviews were tape-recorded, conducted in English or Spanish, and lasted an average of 84 minutes. Additionally, the interviewer wrote a memo after each interview to document first impressions of the interview and other aspects of the experience that could not be captured on audiotape. The interview audiotapes were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber or a native-speaking research assistant.

Data Analyses

The interview transcripts were the primary data analyzed in this study. However, we periodically compared emerging results against interviewer memos to triangulate our findings. We managed the data using Atlas.ti (Friese, 2012). We analyzed the data in the language of the interview using a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1994) that involved an iterative yet systematic process of content analyses, taxonomic organization, and code mapping. We coded each transcript from repeated examinations of the text. The purpose of the content analyses was to become familiar with the breadth and scope of the data. To do this, we coded the responses to each question and then grouped the codes into broader categories around the topic areas in the interview guide.

The taxonomic organization involved breaking down the transcripts into fragments of text as they related to the concept of familism. We first clustered text around single words or phrases and open coded those clusters of text. We then organized the codes into three broad categories of familism generally acknowledged in the literature: (a) strong family identity and attachment (cultural perspective), (b) family network support for both the caregiver and care receiver, and (c) individual sacrifice for the greater good of the care receiver. A primary coder coded all the transcripts, and a secondary coder randomly reviewed 50% of the primary coder’s work as a validation check. The two coders reconciled the coding to reach consensus on the coding after each pass through the data. As we made passes through the data, we refined our coding within the categories and mapped the codes across the three main categories. Specifically, we examined the linkages of codes between the cultural perspective of family, family network support, and individual sacrifice to build thematic content. Upon completion of the taxonomic organization and code mapping, a third coder reviewed all the thematic findings identified by the first two coders. All three coders met repeatedly to reach consensus on the final thematic content reported in this article.

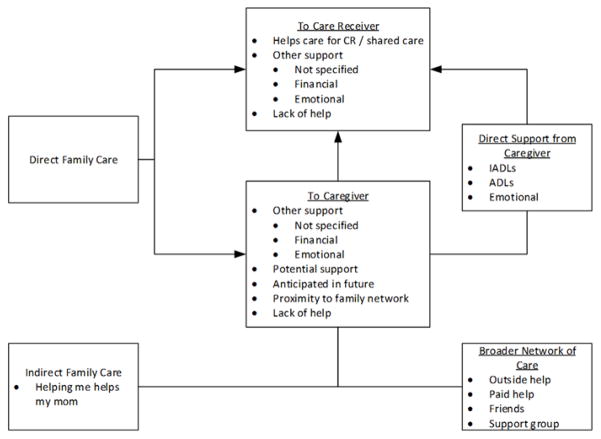

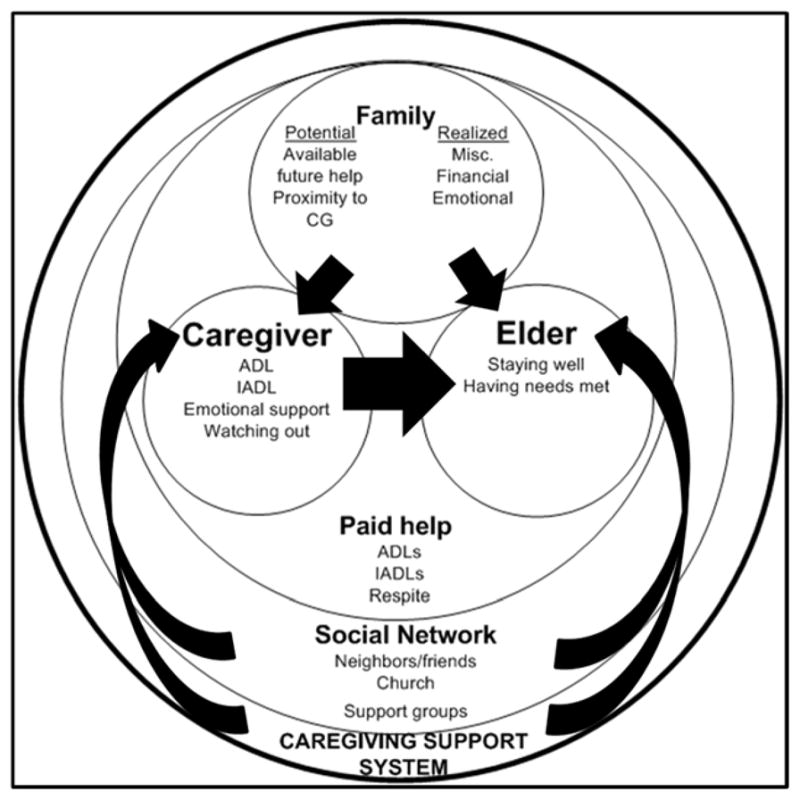

Coding Discrepancies and Development

The most challenging part of the analysis was the time-consuming aspect of checking, verifying, and resolving coding decisions. The most frequent discrepancies arose in examining codes related to family support network. We originally coded family care for the care receiver separately from family support to the caregiver, but we found that we frequently encountered disagreements and inconsistencies in coding because codes such as “paid help” or “helping me helps my mom” reflected direct and indirect forms of support that could be assigned to either category. We ultimately decided on combining the two categories of codes to create a broader domain, “caregiving support system,” to reflect the fluidity in discussions about elder care. Figures 1 and 2 show the progression of coding development and the conceptual thinking for this domain. We conducted this process for all the domains of familism to facilitate identifying thematic content and to increase the rigor of the analyses and validation of our findings. Spanish-language quotes were subsequently translated into English for use in this article, and we used pseudonyms to protect the identity of participants.

Figure 1.

Original Code Mapping for Family Care Network, With Selected Codes.

Note. Bullet points refer to specific codes.

Figure 2.

Final Code Mapping and Conceptualization for Caregiving Support System.

Results

Three primary themes emerged from our analysis of the interview data: (a) family unity, (b) inconsistent family involvement in caregiving, and (c) subjugation of self.

Family Unity

The first theme that emerged from our grounded analysis of caregiving discussions was the caregivers’ view that Mexican families were united. Caregivers described the Mexican family as “united,” “trusting,” “always there,” and “close.” This theme reflected idealized notions often associated with some features of familism, particularly strong family identity and attachment (Almeida et al., 2009; Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003; Sabogal et al., 1987).

Almost all participants viewed the Mexican family in these terms, regardless of their caregiving situations, marital status, family size, or other characteristics. Paz, 28 years old at the time of interview, had been caring for her 81-year-old father for five years because of his foot pain. Her father came from Mexico to live with her, her husband, and their two children because, according to Paz, “when he was in Mexico he would tell us . . . that he [was] alone and had to take care of things himself.” Since he had been living with Paz and her family, she said that “he has more life in him.” In describing the unique characteristics of the Mexican family, Paz shared, “I believe it’s the bond. The bond of the family. The trust [that makes Mexican families special].”

Other caregivers echoed Paz’s view about the Mexican family. Fifty-nine-year-old Norma had been caring for her 73-year-old husband Oscar for nine years since he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Norma and Oscar lived in a modest home in a quiet neighborhood close to where she grew up. Although her brothers had long since moved out of the neighborhood, the siblings remained close. She explained, “We’re always talking to each other; we’re always calling each other, seeing how each other is. . . . I always call and they’re always calling me. So we’re very close.” When asked what made Mexican families different from other families, she answered, “Our [family] trait of being very close knit, very loving . . . that we’re very, very apegado people.” The literal translation of apegado is “attached,” but it implies a stronger sentiment than being close knit—Norma’s use of apegado in the context of family closeness referred to being so close as to being bonded together.

Another caregiver, Gloria, was a 31-year-old unmarried woman with no children and was one of four siblings. At the time of the interview, she shared a small and cluttered two-bedroom apartment with her mother and one of her brothers. The household’s composition was continually in flux depending on the job situations of her siblings, but Gloria had always lived with her mother except for an 18-month period several years prior to the interview. Gloria indicated, “We’re a very close family. If one of us happens to not have a place to live, we are always welcome.” She continued, “We all help each other out. If one has a problem we ask the other, ‘Can you help me with this?’ because that’s how my mom and dad taught us. Not like being in a little ball in our own world not caring for anything.”

Participants also viewed elder caregiving as one feature of a close-knit or united Mexican family that was a normative and cultural obligation. Erika, a 24-year-old single woman with no children, shared a household with her mother, father, two older sisters, and two nephews. Erika quit her job two years before the interview to care full-time for her mother, Alba, who was diabetic and had gone blind from complications from cataract surgery. Erika indicated that she quit her job because “in [our] culture, family comes first.” In another case, Luz Maria cared for her 62-year-old mother, Leti, who suffered from varicose veins and memory problems. At the time of the interview, Luz Maria had been caring for Leti for five years, and she felt that caring for the elderly in their homes or one’s own home helped keep their minds occupied, because they had people around. Luz Maria explained, “We [Mexicans] assume more responsibility in caregiving. As Mexicans, we don’t abandon our parents in nursing homes. We do not leave them alone there.” Laura shared a similar point of view to Luz Maria. At the time of the interview, 64-year-old Laura had been married to her 71-year-old husband for 42 years and had been caring for him for the previous 10 years. Laura’s husband had diabetes and had been on kidney dialysis for the previous five years and, as a result, was wheelchair bound. She attributed her commitment to caring for her husband to her Mexican culture: “We Mexicans are that way. We don’t want to put them in a nursing home. We would rather have them in the house. There is more warmth in the home than in a nursing home. It’s not very pretty there. It’s colder, a bad environment, and everything. There is more familial warmth in the home.”

Laura’s statement illustrates the two aspects of the family that were embedded in elder care, warmth and commitment. In summary, the exemplars presented here represented various family sizes and caregiving situations, including spousal and nonspousal caregiving and long- and short-term caregiving. Yet the notion of the united Mexican family resonated throughout the data, as did the priority of elder caregiving and a warmth that could be found only in the home.

Inconsistent Family Involvement in Caregiving

The second theme that emerged was a seeming contradiction of idealized views on family unity. Participants expressed a closeness, attachment, and commitment to upholding the ideal of shared responsibility, but they reported a lack of consistent family involvement in essential caregiving functions. Unlike the portrayal of the Mexican or Latino family as an institution of mutual support, shared family obligation and interconnectedness (Almeida et al., 2009; Lugo Steidel & Contreras, 2003; Sabogal et al., 1987), almost all participants reported not receiving sustained or comprehensive help from their family networks. Most participants reported that they received help “once in a while,” “sometimes,” or “not very often,” and a few caregivers reported never receiving help from siblings, children, or other family members. Regardless of the size of the family network or household, almost all participants indicated that for support they relied on fewer family members than were potentially available to them. Thus, the kin-work in and across households was not collective or family centered, as dictated by familistic principles.

Describing her views on the family’s lack of involvement in caregiving, Iris commented on her life circumstances. At age 26, Iris had four children and was engaged to her longtime boyfriend. At the time of the interview, Iris had been caring for 3.5 years for her 65-year-old grandmother, who suffered from high blood pressure. Here, Iris responded to the question about how she came to be her grandmother’s caregiver, and in doing so, she shared her views about her grandmother’s own children not being involved in caregiving activities:

My grandma, she raised me and I have been one of her favorites . . . and now that I’m older, I’m the one that does start taking care of her whenever she needed to go to her doctors’ appointments, market. . . . My aunts, they have their own lives, but they were too busy or always had excuses. So, I would be the one to go to her [grandmother] and do whatever she had to do and watch over her. . . . It did bother me because those are her children. . . . I mean, my oldest aunt . . . [she] has her life and her husband and what her husband’s going through . . . [but] sometimes it is important, like I said, to stop what you’re doing to be there for your mother.

In a similar circumstance, Ofelia was a 35-year-old single woman who had been caring for her 75-year-old father for one year and her 71-year-old mother for 21 years. Her father had brain cancer and her mother had diabetes, arthritis, and osteoporosis. Although Ofelia had two older siblings, she had always been responsible for caring for her parents, ever since she was a teenager. Ofelia reflected on the lack of help from her siblings and stated, “I asked them to do me a favor and go Saturday for a couple of hours to help me. Sometimes they don’t even go. They’re like, ‘We’re tired. We’re sick.’ Thank you. Welcome to my world, you know?”

Olga had lived with her parents off and on for her entire adult life. She began caring for her mother Rosa 10 years before the interview, after she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. For the previous four years, she had been living with her mother as a full-time caregiver. Olga was 50 years old and had never been married or had children. She had a brother and sister who helped her occasionally by taking Rosa to Mass on Sundays and by giving Olga money to help support herself, as she had quit her job and college to care for her mother. Both she and her mother battled depression throughout their lives, which put strain on their relationship and made coping with caregiving difficult at times for Olga. In discussing the minimal involvement of her siblings in Rosa’s care, Olga shared:

You would think that a family does [help caregivers], but families take people for granted . . . somebody, a sister can do it [help care]. But it’s not done. Like I said, we’re taken advantage of, or we’re part of the furniture. . . . [I]t’s for some reason we’re doing this, and it’s probably because we’ve always been the ones that are relied upon. We’re expected to do it. Not only by ourselves, but the assumption is made that we’re going to do this. And I just wish that there was some concern [about me].

A subtheme of the family’s inconsistent involvement in elder caregiving was the conflict it created in family relations. Sara, a 23-year-old single woman with one small child, had been caring for her 62-year-old mother for the previous nine years. Her mother suffered from depression, high blood pressure, and migraine headaches. Sara indicated that her father and siblings did not help her with her mother’s care because they saw it as a burden to them. Sara commented on the strife and blaming it caused in the family:

[My brother] doesn’t want to take any responsibility. If I tell my brother my mom is sick, [he says,] “What do you want me to do [about it]?” . . . [He tells me] “It’s your fault she’s like this,” or “You didn’t do this for her,” or “You didn’t do that.” That’s why I thought it’s [a] burden for him because he doesn’t . . . rather than telling me “Don’t worry I will help you,” no, [he says] “It’s your fault she’s like this.”

Twenty-four-year-old Erika described her frustration and disapproval of her siblings for their nonchalant attitude toward caregiving, although she also had stated that family came first. The following reflects how Erika’s sisters did not help with caring for her mother and her feelings about it:

Cleaning, cooking, like when my mom is here [at home] they [the sisters] will not even help me out with my mom. They only help me out like “Oh my God, my mom’s in the hospital. Let’s go.” It’s like, dude, no, they just want to be there for her when she’s sick but . . . when she’s at home they don’t want to help me. I’m the one that’s [looking] after my mom, I’m the one that’s like “Oh Mommy, I’m going to the store,” or, like, my mom doesn’t even feel comfortable asking them for anything because they make a face [le hacen mala cara] or they say no or they just leave her there. And . . . that pisses me off. Why are you treating my mom like that? [Interviewer: Why do you think they’re like that?] ’Cause they’re selfish. That’s what I think.

Finally, Victoria, a 57-year-old married woman with two kids, had been caring for her 84-year-old father for 30 years. Victoria’s mother had died from cancer two years before the interview, and her father suffered from diabetes and was wheelchair bound. After being asked how many siblings she had, Victoria shared that despite having two brothers, they never helped her care for her father until a few weeks before the interview, when they placed him a nursing home:

I have two brothers, one older, one younger. I’m the middle kid, but I did ask them for help many, many times. To come and keep him company while I went out, but my brothers did not. My older brother is taking [care of] my dad’s financials [now], thinking he’s able to help him that way. What my dad needed [then] was basically emotional, mental, spiritual care. They didn’t give him that. Me and my dad, we always bumped heads, but I was always here caring for him and listening to him. My siblings didn’t help. . . . They didn’t want to deal with my dad’s attitude. . . . It was just like, “Okay, these children forgot who their parents are.” And they stayed away [until now].

Expressing a similar sentiment, Micaela, a 25-year-old married woman with three small children, had been caring for three years for her 56-year-old mother-in-law, who suffered from diabetes and heart problems. We asked her whether it bothered her that her husband’s family members did not help care for her mother-in-law, and she answered, “Not really.” When we asked how she felt about being the primary person to care for her mother-in-law, Micaela stated, “Sometimes it does [bother me] when I feel very stressed or tired, of course. You know, because like I tell him [her husband], it’s more their obligation [his family] than mine, but I [do it] in order to help him.”

In summary, women experienced frustrations and tensions being the sole caregiver in their families. The distribution of family labor was not equal in their networks, which suggests a lack of shared understanding, responsibility, and socialization of the caregiver role, even among other women in the family.

Subjugation of Self

The third theme to emerge from our grounded theory analysis was the subjugation of self in the pursuit of caregiving. Consistent with previous research on self-sacrifice and la madre abnegada (García & de Oliveira, 1997; Hubbell, 1993; Peñalosa, 1968), participants viewed elder caregiving as a priority over their personal and professional lives and interpersonal relationships. Prioritizing the needs of the care recipients came at price for all participants, including social isolation, financial hardships, and changes in living arrangements. For example, 50-year-old Olga quit her job to care for her ailing mother. She admitted, “It’s affected me, staying with my mom, of giving up a lot of my own life for her care.” However, she also stated, “In many ways, I get a lot out of it, I really do, and I try to look at that.” Fifty-seven-year-old Angelica was the caregiver for her 81-year-old mother, Lupe, who suffered from Alzheimer’s disease. Angelica and her husband, Roberto, used to have their own apartment, but as Lupe’s health deteriorated, Angelica and Roberto decided it was time to move in with Lupe, where they could keep better watch over her. Moving into her mother’s house was a willing sacrifice for Angelica, but she indicated, “The hardest part is when I try to look for something and I can’t find it.” Angelica was determined not to move around Lupe’s things because “I want her to be in her house.” However, Angelica admitted, “It’s hard and it’s material and I try not to dwell on that but it does affect [me], it does affect [me]. I don’t have a house.” Olga and Angelica’s experiences illustrate ways in which they and other caregivers subjugated themselves in the interests of caring for their elderly family members. Additionally, the descriptions of their transitions out of work and migration to new households reflect a fulfillment of familial obligations in their family scripts, even when scripts were not shared within the network.

While most caregivers responded to their situations with expressed frustration, a sense of loss, or even antagonism toward other noninvolved family members, a few caregivers seemed to assume the role without begrudging anyone or the situation itself. Not unlike other caregivers who displayed a sense of love, compassion, and responsibility, these caregivers also saw the obstacles that prevented family members from being involved in caregiving, and in some cases, they offered reasons for others’ lack of participation. One such caregiver was 66-year-old Ana. She and her 67-year-old husband, Lalo, had been married for 46 years and had nine grown children. For the previous four years, Ana had been caring for her husband, who was wheelchair bound because of swollen legs due to kidney dialysis. She explained why none of her adult children helped care for their sick father: “All of my kids work, and they all live very far from where I live. The only one that lives closest is one of my daughters . . . she works ten hours a day, she can’t [help], and she has kids too. . . . It’s impossible for them to come help me.” Another caregiver was 59-year-old Monica. Expressing a heightened sense of moral responsibility, Monica had spent the previous three years of her 45-year marriage caring for her husband, Raul, who had complications from diabetes. Monica was her husband’s sole caregiver despite having five adult children living nearby. Monica stated simply, “God gives us wisdom and understanding that this is how things are going to be . . . that’s my way of thinking.”

Discussion

In this study we used kinscripts as a frame to examine how Mexican-origin women viewed elder care in terms of their role as caregiver in the context of their family circumstances and according to familistic principles commonly found in the literature. Our results suggest a gap between the caregiving ideal and reality that reflects a close but thinly knit network of elder care. This gap is not fully accounted for in the existing paradigm of familism. For example, familism has components of family obligation and availability of familial support, as well as perceived support and expectations of assistance from other family members (Sabogal et al., 1987). These components were not realized in the lived experiences of the caregivers in this study. These findings are consistent with a recent study on the impact of familism on Latino families caring for relatives with Alzheimer’s disease; that study found that some caregivers struggled with the espoused values of familism and their caregiving duties (Gelman, 2014). Additionally, the women in this study reported stress, burden, and even resentment, in support of Losada et al.’s (2010) findings on the multidimensionality of familism, specifically that family obligation and perceived family support can influence caregiver burden.

However, our results suggest that familism as an ideal remains strong among the Mexican-origin women in our study. The notion of apegado, or the “close-knit” family, that emerged in our study is consistent with other studies examining mothers’ values for their children (Arcia & Johnson, 1998) and mutuality as a motive for elder caregiving (Kao, Lynn, & Crist, 2013). We also found that participants had very positive views of the Mexican family and subjugated themselves to fulfill caregiving responsibilities. These findings suggest that participants fulfilled the role of la madre abnegada (Hubbell, 1993) and that the marianismo role indeed extends to women’s kinscripts of elder care. From a kinscripts perspective, the women’s experiences reflected a family-centered ideology and culturally specific recruitment to the family’s production of elder care. However, their kinscripts did not appear to be universally shared by other members in their family networks. Most, if not all, caregivers performed caregiving labor without ongoing support or involvement of their families, as would be expected under a guiding principle of familism. Participants also interpreted their caregiving experiences in the purview of the idealized family despite the conflict of those views, their own families, and the actual support they received from family members. Our findings also suggest that familism is gendered when it comes to elder care and that women sacrifice themselves to navigate the gap between ideal and reality. Some women subjugated themselves through silencing, and others vocalized the hardships involved in making sacrifices. All women created scripts that supported their efforts to meet their perceived familial obligations, thereby compensating for the deficiency in family support. These findings are alarming to the extent that Mexican-origin women are trying to achieve an ideal that is not sustainable. Specifically, the effects of informal caregiving on caregiver health are significant, including stress, burden, multiple role strain, and death (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2005, 2007; Schulz & Beach, 1999). Latino caregivers are more likely to be in more burdensome caregiving situations than their non-Latino caregiving counterparts (Evercare & National Alliance for Caregiving, 2008) and to underutilize formal care services relative to other racial/ethnic minority groups (Hinton & Levkoff, 1999; Gallagher-Thompson et al., 2003). Thus, the consequences of caregiving could be compounded for Mexican-origin women who face negotiating the gap between their caregiving ideals and their caregiving realities.

A potential explanation for our seemingly contradictory findings is that the concept of familism is evolving. First, we found that participants fulfilled the marianismo role, acted in ways consistent with being madres abnegadas, and had idealized notions of the family. However, we also found that they were not passive followers; they voiced their complaints about the lack of family involvement. These findings suggest that a shift may be occurring in gendered ideologies of Mexican-origin women whereby they are becoming more macho, consistent with a recent study on Mexican women scientists in the workplace (Englander, Yáñez, & Barney, 2013). Second, women’s kinscripts indicated that the structure, timing, and socialization of elder care is specific to the family context, which suggests that familism is not a static or universal construct.

Another potential explanation for our findings is that familism may have always been an idealized cultural notion, at least in terms of elder caregiving. Family closeness and support may truly exist as long as there is no significant family need, such as long-term elder care, to upset the balance. This explanation might explain how the women in this study reconciled their acceptance of familism with the lack of support from their kin networks. Thus, our study uncovered discrepancies between the ideology and the enactment of familism that have not been detected in prior studies.

There are some important limitations to our study. First, men were purposely excluded from this study. We realize that focusing solely on the experiences of women does not advance our understanding of gender differences in the experience of caregiving. More research is needed to examine men’s roles in the family’s production of elder care and under the purview of familism. Additionally, we interviewed each participant only one time. Multiple interviews would have given participants the opportunity to think through their experiences, providing richer data. Last, the generalizability of our study is limited because of the sample’s characteristics, which could have influenced the ways participants socially constructed their lived realities. More research is needed to measure empirically the themes identified in this study, especially the cultural reasons for providing care despite the hardships of the undertaking.

In conclusion, a kinscripts framework allowed us to expand our understanding of familism to show that it is socially constructed in ways that are not reflected in its current conceptualizations and definitions in the literature. Indeed, kinscripts may inform familism by creating culturally based ideologies of family and kinship relations that appeal to, guide, or enlist certain family members into a self-sacrificing role while other family members avoid such work. Further, our findings support two of the three conclusions drawn by Wallace and Facio (1987). Our findings indicate that the extended family does provide social support to the elderly but also tends to perpetuate traditional gender role expectations. We conclude that familism provides a system of support for the elder—either directly from the caregiver or indirectly from the family network via the caregiver—but it does not provide a system of support for the caregiver. More research is needed to refine familism as a theoretical perspective to explain how Mexican-origin families negotiate and construct elder care over the family life course.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Aetna Foundation (20072361 to C.A.M.-L.), the Drew/UCLA Project Export (2P20MD000182-06), the UCLA Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (P30AG021684), and the National Institutes of Health (1K01AG033122 to C.A.M.-L.). The authors wish to thank research assistants Monica Ayala-Rivera, Erika S. Farkas, Esmeralda Pulido, and Ana Reynoso for their contributions to this study.

Contributor Information

Carolyn A. Mendez-Luck, Email: carolyn.mendez-luck@oregonstate.edu, Oregon State University

Steven R. Applewhite, Email: sapplew@central.uh.edu, University of Houston.

Vicente E. Lara, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

Noriko Toyokawa, Email: ntoyokawa@csusm.edu, California State University, San Marcos.

References

- Abel EK. Who cares for the elderly? Public policy and the experiences of adult daughters. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1991. pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J, Molnar BE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Ethnicity and nativity status as determinants of perceived social support: Testing the concept of familism. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1852–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Community Survey. Hispanic or Latino origin by specific origin. 2011a [Data file B03001]. Created using FactFinder at http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- American Community Survey. Language spoken at home by ability to speak English for the population 5 years and over (Hispanic or Latino) 2011b [Data file B16006]. Created using FactFinder at http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- American Community Survey. Place of birth (Hispanic or Latino) in the United States. 2011c [Data file B06004L]. Created using FactFinder at http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- American Community Survey. Poverty status in the past 12 months by age (Hispanic or Latino) 2011d [Data file B17020L]. Created using FactFinder at http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- Arcia E, Johnson A. When respect means to obey: Immigrant Mexican mothers’ values for their children. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1998;7(1):79–95. doi: 10.1023/A:1022964114251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. 2. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Blieszner R, Hamon RR. Filial responsibility: Attitudes, motivators, and behaviors. In: Dwyer JW, Coward RT, editors. Gender, families and elder care. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges JC. The Mexican family. In: Das MS, editor. The family in Latin America. New Delhi, India: Vikas; 1980. pp. 295–334. [Google Scholar]

- Buss MK, DuBenske LL, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Cleary JF. Patient/caregiver influences for declining participation in supportive oncology trials. Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2008;6(4):168–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Perez FV, Castillo R, Ghosheh MR. Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2010;23(2):163–175. doi: 10.1080/09515071003776036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crist JD, McEwen MM, Herrera AP, Kim S-S, Pasvogel A, Hepworth JT. Caregiving burden, acculturation, familism, and Mexican American elders’ use of home care services. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal. 2009;23(3):165–180. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.3.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado M. Social work with Latinos: A cultural assets paradigm. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of race, ethnicity, and culture in caregiving research: A 20-year review (1980–2000) Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):237–272. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams SW. Recruitment and retention strategies for longitudinal African American caregiving research: The Family Caregiving Project. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;165(5):137S–156S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englander K, Yáñez C, Barney X. Doing science within a culture of machismo and marianismo. Journal of International Women’s Studies. 2013;13(3):65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic Population: 2010 (Census Briefs C2010BR-04) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Evercare & National Alliance for Caregiving. Evercare study of Hispanic family caregiving in the US: Findings from a national study. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.caregiving.org/data/Latino_Caregiver_Study_web_ENG_FINAL_11_04_08.pdf.

- Falicov CJ. Changing constructions of machismo for Latino men in therapy: “The devil never sleeps. Family Process. 2010;49(3):309–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkler K. Women in pain: Gender and morbidity in Mexico. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Friese S. Qualitative data analysis with Atlas.ti. London, UK: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Solano N, Coon D, Areán PA. Recruitment and retention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research: Issues to face, lessons to learn. Gerontologist. 2003;43(1):45–51. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García B, de Oliveira O. Motherhood and extradomestic work in urban Mexico. Bulletin of Latin American Research. 1997;16(3):367–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-9856.1997.tb00059.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman CR. Familismo and its impact on the family caregiving of Latinos with Alzheimer’s disease: A complex narrative. Research on Aging. 2014;36(1):40–71. doi: 10.1177/0164027512469213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez NC, Germán M, Fabrett FC. U.S. Latino youth. In: Chang EC, Downey CA, editors. Handbook of race and development in mental health. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann MC. The ethnographic (g)ambit: Women and the negotiation of masculinity in Mexico City. American Ethnologist. 1997;24(4):833–855. [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks J. Qualitative research: Contributions and advances. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 4. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 52–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton WL, Levkoff S. Constructing Alzheimer’s: Narratives of lost identities, confusion, and loneliness in old age. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 1999;23:453–475. doi: 10.1023/A:1005516002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell LJ. Values under siege in Mexico: Strategies for sheltering traditional values from change. Journal of Anthropology Research. 1993;49(1):1–16. doi: 10.1177/1470593109355249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John R, Resendiz R, De Vargas LW. Beyond familism? Familism as explicit motive for eldercare among Mexican American caregivers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 1997;12(2):145–162. doi: 10.1023/A:1006505805093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao HFS, Lynn MR, Crist JD. Testing of applicability of Mutuality Scale with Mexican American caregivers of older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2013;32(2):226–247. doi: 10.1177/0733464811416813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of American Geriatrics Society. 1983;31(12):721–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE. Real and ideal extended familism among Mexican Americans and Anglo Americans: On the meaning of “close” family ties. Human Organization. 1984;43(1):65–70. doi: 10.17730/humo.43.1.y5546831728vn6kp. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner G. AARP Caregiver Identification Study. Washington, DC: AARP; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine SE, Sunderland Correa C, Tapia Uribe FM. Marital morality of Mexican women: An urban study. Journal of Anthropological Research. 1986;42(2):183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Márquez-González M, Knight BG, Yanguas J, Sayegh P, Romero-Moreno R. Psychosocial factors and caregivers’ distress: Effects of familism and dysfunctional thoughts. Aging and Mental Health. 2010;14:193–202. doi: 10.1080/13607860903167838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losada A, Robinson Shurgot G, Knight BG, Márquez M, Montorio I, Izal M, Ruiz MA. Cross-cultural study comparing the association of familism with burden and depressive symptoms in two samples of Hispanic dementia caregivers. Aging and Mental Health. 2006;10(1):69–76. doi: 10.1080/13607860500307647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo Steidel A, Contreras JM. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2003;25:312–330. doi: 10.1177/0739986303256912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magana S, Schwartz SJ, Rubert MP, Szapocznik J. Hispanic caregivers of adults with mental retardation: Importance of family functioning. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2006;111(4):250–262. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[250:HCOAWM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Parsai M, Kulis S. Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2009;18(3):203–220. doi: 10.1080/15313200903070965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Depp C, Rabinowitz YG, Wilson-Arias E, Kraemer HC, … Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnicity and time to institutionalization of dementia patients: A comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(7):1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Kennedy DP, Wallace SP. Concepts of burden in giving care to older relatives: A study of female caregivers in a Mexico City neighborhood. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2008;23(3):265–282. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9058-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Kennedy DP, Wallace SP. Guardians of health: The dimensions of elder caregiving among women in a Mexico City neighborhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(2):228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Luck CA, Trejo L, Miranda J, Jimenez EJ, Quiter ES, Mangione CM. Partnering with community based organizations in recruiting Mexican-origin populations in East Los Angeles. Gerontologist. 2011;51(S1):94–105. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo C, Duarte CS, Shen S, Blanco C, Canino G, Bird HR. Parental familism and antisocial behaviors: Development, gender, and potential mechanisms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nader L. Subordination of women in comparative perspective. Urban Anthropology. 1986;15(3–4):377–397. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2006 with chartbook on trends in the health of Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Author; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DL. Self-identifying as a caregiver: Exploring the positioning process. Journal of Aging Studies. 2007;21(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2006.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JL. Women and social change in a Mexican town. Journal of Anthropological Research. 1977;33(1):73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Peñalosa F. Mexican family roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1968;30(4):680–688. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources, and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: A meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology. 2007;62(2):126–137. doi: 10.1002/gps.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochelle AR. No more kin: Exploring race, class, and gender in family networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez MD, Rodriguez J, Davis M. Recruitment of first-generation Latinos in a rural community: The essential nature of personal contact. Family Process. 2006;45(1):87–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Burton L. Mothering through recruitment: Kinscription of nonresidential fathers and father figures in low-income families. Family Relations. 2007;56(1):24–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00437.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy K, Zvonkovic A, Goldberg A, Sharp E, LaRossa R. Sampling richness and qualitative integrity: Challenges for research with families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015;77(1):243–260. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozario PA, DeRienzis D. Familism beliefs and psychological distress among African American women caregivers. Gerontologist. 2008;48(6):772–780. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.6.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal F, Marin G, Otero-Sabogal R, Marin B, Perez-Stable E. Hispanic familism and acculturation: What changes and what doesn’t? Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9:397–412. doi: 10.1177/07399863870094003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santisteban DA, Coatsworth JD, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Beyond acculturation: An investigation of the relationship of familism and parenting to behavior problems in Hispanic youth. Family Process. 2012;51(4):470–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach A, Kellam R, Ong N, Baskin A, Goldstein C, Fox P. Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: Lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47(1–2):133–156. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurgot GR, Knight BG. Influence of neuroticism, ethnicity, familism and social support on perceived burden in dementia caregivers: Pilot test of the Transactional Stress and Social Support Model. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2005;60:P331–334. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobralske M. Machismo sustains health and illness beliefs of Mexican American men. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2006;18(8):348–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB, Burton LM. Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1993;24(2):157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Staton RD. A comparison of Mexican and Mexican-American families. Family Coordinator. 1972;21(3):325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- Torres JB, Solberg VSH, Carlstrom AH. The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(2):163–181. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. East Los Angeles CDP quickfacts from the US Census Bureau. 2010 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06/0620802.html.

- Wallace SP, Facio EL. Moving beyond familism: Potential contributions of gerontological theory to studies of Chicano/Latino aging. Journal of Aging Studies. 1987;1(4):337–354. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(87)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn G, Knight B, Jeong H, Benton D. Differences in familism values and caregiving outcomes among Korean, Korean American, and White American caregivers. Psychology and Aging. 1999;14:355–364. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.14.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]