Abstract

The goal of this study was to identify strategies that could yield more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts. In-depth interviews were conducted with 30 young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) living in Baltimore, Maryland. The sample had an equal number of regular and infrequent church attendees. Nearly one-fourth of the sample was HIV-positive. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed inductively using a qualitative content analytic approach. Two main recommendations emerged for churches to offer more inclusive HIV prevention efforts: (1) reduce homosexuality stigma by increasing interpersonal and institutional acceptance, and (2) address the sexual health needs of all congregants by offering universal and targeted sexual health promotion. Thus, results support a tiered approached to providing more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts. We conclude that Black churches can be a critical access point for HIV prevention among YBMSM and represent an important setting to intervene.

Keywords: HIV prevention, black men who have sex with men, church-based, qualitative

Introduction

Black churches (defined as congregations whose members are predominantly African American) around the U.S. have recognized the need for churches to play a greater role in HIV prevention (Nunn, et al 2012; Pichon, Williams, & Campbell, 2013). Some of the initial responses to the HIV epidemic from Black churches were viewed as unsupportive, critical of victims, and stigma-reinforcing (Smith, Simmons, & Mayer, 2005). Over time, Black churches began to take more active roles in HIV prevention efforts (Agate, et al., 2005; Berkley-Patton et al., 2010; Griffith, et al., 2010; Williams, Palar, Derose, 2011). Recent research findings suggest that HIV prevention education, interventions and screening are welcome by some congregations and feasible to implement in some Black churches (Pichon and Powell, 2015; Weeks et al., 2016). Most church-based HIV prevention efforts have been developed in partnerships with outside organizations and tailored to target audiences such as youth and women (Francis & Liverpool, 2009; Stewart, 2014; Wingood et al., 2013). However, church-based HIV prevention efforts have not focused on the group most profoundly affected HIV – young black men who have sex with men (YBMSM). The goal of this study was to identify strategies that could yield more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts.

Black Churches and Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM)

There is a plethora of research describing the religious experiences and church involvement of Black MSM. For example, researchers have reported that many Black MSM attend church, view church attendance and religious worship as deeply intertwined with family and community life, and use spiritual practices to cope with life’s challenges (Balaji et al. 2012; Cutts and Parks, 2009; Foster, Arnold, Rebchook & Kegeles, 2011; Jeffries, Dodge, & Sansdfort, 2008; Quinn, Dickson-Gomez, & Kelly, 2015; Woodyard, Peterson, & Stokes, 2000). Other studies have also highlighted the psychosocial benefits of religious involvement among Black MSM (Pitt 2010; Walker and Longmire-Avital 2013). However, most commonly, researchers have described experiences of homophobia, heterosexism and stigmatization within Black churches towards Black MSM (Harris 2009; Miller 2007; Valera and Taylor, 2011).

The potential for Black churches to perpetuate homosexuality stigma has been of great concern (Altman et al., 2012; Haile, Padilla, and Parker 2011; Jeffries, Marks, Lauby, Murrill, & Millett, 2013). For example, homosexuality stigma is the social devaluation of people who are thought to be homosexual; it refers to personal experiences, interactions and stereotyping experiences among non-heterosexual individuals, as well as broader social and cultural factors such as power relations, community values, and historical practices (Stuber, Meyer, & Link, 2008; Wilson, 2014). For many, stigma and homophobia experienced within their families and churches decrease coping and increase experiences of emotional distress (Balaji, et al., 2012; Choi, et al., 2011; Radcliffe, et al., 2010). Homosexuality stigma has been linked to greater isolation from relatives and friends, and poorer health (Hightow-Weidman, et al., 2011; Mustanski, Newcomb, Du Bois, Garcia, & Grov, 2011). Homosexuality stigma has also been negatively associated with engagement in the HIV care continuum, which includes HIV testing, a reduction of HIV risk behaviors, and linkages to HIV care among infected individuals (Parker and Aggleton, 2003; Vanable, Carey, Blair & Littlewood, 2006).

In summary, Black churches continue to be strong presence in the lives of many Black MSM, despite negative associations and potential rejection. However, researchers have not yet developed concrete solutions to address more inclusive HIV prevention efforts in churches. Thus, additional research is needed to translate previous research findings into practice.

Current Study

YBMSM between the ages of 13 and 24 years old continue to be disproportionately burdened by HIV, accounting for approximately 45% of all new cases of infection among men who have sex with men (CDC, 2015). The Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Strategy (Baltimore City Commission on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment (BCCHIV), 2011) suggested that HIV prevention efforts could be improved by increased collaborations with religious organizations. Best practices for incorporating the HIV prevention needs of YBMSM in churches are lacking, despite the fact that HIV incidence rates have continued to rise among this group (Prejean et al., 2011). Black churches are well positioned to be a strategic partner in the fight against HIV/AIDS among Black MSM (BCCHIV, 2011). However, few studies have outlined approaches for Black churches to engage in HIV prevention with BMSM (Buseh et al, 2006; Hill and McNeely, 2013). To address the gap in the literature, the goal of this study was to identify strategies that could yield more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts.

Methods

This qualitative study is a part of the ongoing Social Networks and Prevention (SNAP) Project, a larger randomized control trial of an HIV prevention intervention for adult MSM and their social networks, conducted in Baltimore, Maryland. The primary aim of SNAP was to develop an intervention for MSM (ages 18 and older) to become peer mentors who talk to their social networks about HIV and STI risk reduction. The current study focuses on data collected through a supplemental study, Prevention in Churches (PiC) Project, which exclusively examined churches as a social network among YBMSM (ages 18-25), given that YBMSM have one of the highest rates of HIV infection in Baltimore, Maryland (German, et al., 2011). A bidirectional recruitment strategy was employed between the two projects, whereby participants in both studies were informed of the affiliated research project. However, to protect confidentiality, participants were not questioned about their participation in any other research studies. The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through venue-based outreach (local bars and clubs, community-based organizations and events, and churches), street outreach, and referrals, including those from the parent study. The study team approached potential participants, described the purpose of the study and screened for eligibility. Participants were recruited using a criterion sampling technique (Patton, 2002). To participate in the parent study, men had to speak English, be 18 years of age or older, and report having had sex with another man in the past year. To address the experiences of inner-city YBMSM, additional inclusion criterial were added. To be eligible to participate, the men had to meet the following criteria: (1) speak English; (2) identify as Black/African American; (3) live in Baltimore, Maryland; (4) be between the ages of 18 and 25 years old; and (5) report having had sex with another man in the past year. Eligible participants were given the option to set up a time, date and location for an interview, or to provide contact information at which to be reached to establish an interview plan at a later time.

Each participant and study team member mutually agreed upon the interview date, time, and location. Participants were required to provide oral consent prior to the start of the interview. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire, and then an interview. Interviews were conducted by the first author and two trained female undergraduate research assistants. Interviews ranged from 17 minutes to 66 minutes in duration. All interviews were digitally recorded. Interviewers also took field notes during and immediately after the interviews. At the end of the interview, all participants were compensated $25 and given a flyer describing the parent study.

Measures

Church attendance was measured during the initial screening. All eligible participants were asked how often they attend church. Participants who reported they attended church once a month or more were classified as regular attendee. If they attended less than once a month, but more than once a year, they were classified as infrequent attendees.

A semi-structured interview guide was used to conduct the in-depth interviews. The interview guide consisted of 12 major questions with a series of probes to help interviewers obtain rich responses. Questions were divided into three categories: personal history (e.g., what do you like most/least about the last church you attended?), sexual health related questions (e.g., if you suspected you had and STI or HIV, what would you do?), and sexual health programs in congregations (e.g., what types of church programs, activities or events related to sexual health and HIV prevention would you be willing to support?).

Participants completed a nine-item demographic questionnaire. The questionnaire asked participants to provide basic information such as their age, highest education level, and HIV status. Substance use was measure using two items which asked (1) how often they drank alcohol and (2) if they were currently using any of the following drugs: cocaine, crack, marijuana, methamphetamines, or non-prescription opiates. Sexual orientation was not measured.

Data Analysis

The digital recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim by an online transcriptionist service. The transcripts were verified by the research team member who completed the interview, who corrected any discrepancies or omissions using field notes taken during and after the interview. Transcripts were then imported into the qualitative software program, Atlas.ti 7.0, to assist in data analysis. Transcripts were analyzed inductively using a qualitative content analytic approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Using this approach, a coding manual was created by comparing the interview transcripts with one another and then categorizing common responses. Peer debriefings were used to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of our findings (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Toma, 2006). Research team members met weekly to compare and contrast categories identified through independent open-coding. The final coding manual contained 47 codes. Codes describing participants, their connections to churches, and recommendations for HIV prevention in Black churches are highlighted in this paper. Ultimately, themes were developed based on patterns and topics that persisted throughout the interviews. Demographic data was analyzed using SPSS 22.

Results

Thirty YBMSM living in Baltimore, MD participated. Participants ranged from 18 to 25 years old (M = 22.5 years). Over half (53%) of participants reported attending church once a month or more (regular attendees). Over 80% of participants reported high school completion. Twenty-three percent of the sample (n = 7) was HIV-positive.

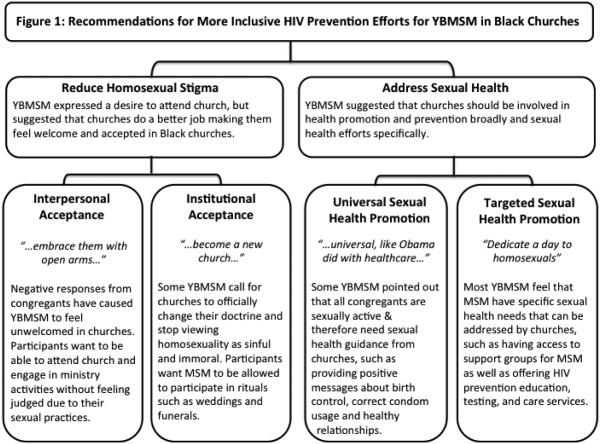

Participants identified two main strategies for churches to address HIV prevention efforts among YBMSM: (1) reduce homosexuality stigma, and (2) address the sexual health needs of all congregants. Within each theme, subthemes emerged that elaborate on specific and practical applications of each recommended strategy. Results are summarized in Figure 1 and explained below.

Figure 1.

Recommendations for More Inclusive HIV Prevention Efforts for YBMSM in Black Churches

Reduce Homosexuality Stigma

Reducing homosexuality stigma in churches was considered an essential component in church-based HIV prevention for YBMSM. Both regular and infrequent church attendees reported feeling a sense of connection and nostalgia for attending church with their families; however, in most cases their fond childhood memories of the church were tempered with currently feeling unwelcome due to their sexual partner selection. Many participants stated that church leaders and congregants stared at them in church in a judgmental manner. For example,

They are the other people, where this is like, "I don't go there, go to church," because when they're going to church, it’s “look at that fag, look at that fag”…They don't want to deal with it. – 23 year old, regular attendee, ID #19

As noted above, the stigma related to homosexuality prevented some from feeling comfortable in churches and was a significant barrier to church attendance for others. Still, many participants believed that homosexuality stigma could be reduced by fostering an accepting environment. Two perspectives emerged as to how church leaders could reduce homosexuality stigma: a) interpersonal acceptance and b) institutional acceptance

Interpersonal acceptance

All participants discussed the ways in which some churches negatively respond to Black MSM. Interpersonal acceptance reflected participants’ (i.e. YBMSM) desire to attend church and participate in church activities without feeling judged and unwelcome by other congregants because of their sexual preferences. Almost all participants, including infrequent attendees, expressed this need to be recognized in Black churches by their humanity, talents, and gifts from God, not by their sexual partners. Instead, participants advocated for their conflict-free engagement in basic church activities such as attending worship services, singing in the choir, or participating in the dance ministry. As several participants explained,

If you want people to come with open arms, you have to embrace them with open arms. Don't embrace me with whispers and snickering. – 22 year old, regular attendee, ID #05

A lot of churches are judgmental. That's one place that shouldn't be. They should be willing and wanting to welcome you with open arms no matter who you are. – 19 year old, infrequent attendee ID #06

To the pastor, try to emphasize that God loves you. He [God] hates your sin. He loves you, but He hates your sin – 24 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #10.

The one thing I really hear a lot is that God loves everybody for who you are. Last weekend I went to Boston. I went to the Pride Parade. There were 30 or 40 churches in the Pride Parade. They were like, "We love you." I was like wow, I wish I had that. – 20 year old, regular attendee, ID #22

These participants acknowledged some churches’ stance that homosexuality was a sin, but did not see the sin of homosexuality as being any worse than any other type of sin. These excerpts reflect a common sentiment among YBMSM that churches should be open to all regardless of the sins they commit.

Institutional Acceptance

Institutional acceptance was described as a long-term pursuit for Black churches to address HIV prevention among YBMSM for some participants. Institutional acceptance referred to the reinterpretation of homosexuality and doctrinal changes that align with this perspective among Black churches. These participants suggested that churches’ stance on homosexuality as a sinful and immoral is outdated and out of touch with current society. They called for churches to “wake up to reality” and become more progressive in their thinking around sexual health. Participants’ aspirations for institutional changes within churches were discussed frustration.

What the churches need to do is they need to understand that it [homosexuality] exists. It's living. It's within your communities. It's within your churches. It's sitting in your damn pews. – 25 year old, regular attendee, ID #03

The church definitely needs to be very progressive and become a new church because all these old churches, established churches are stuck in their ways. It's going to take a progressive, new leader or new pastor with a vision to really see the whole picture. – 25 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #20

They have to change the protocol, change the rules, change a lot. A lot will have to change within the church. They would have to accept a lot more. They would have to accept that people in the congregation are having sex. Everybody's not abstinent. People are having sex and there are STDs out here. It's out here. – 25 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #24

As noted above, some participants believed that institutional changes within the church and among faith leaders were imperative, but not easy. Denying inclusion in church rituals was viewed as the most egregious offense to acceptance according to participants. One participant said,

I went to a funeral for a transgender. She got shot and died. No church would accept her body, because she was transgender. That's the realization of churches. She had to have her funeral in a recreational center. – 24 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #27

For these participants, full acceptance of homosexuality into the churches translated into integrating sexual minorities into their theological framework, as well as including them in church rituals and traditions, such as weddings and funerals. The majority of participants did not expect churches to condone homosexuality or change their doctrinal stance on same sex relationships. Thus, participants offered little hope that such systematic changes would materialize.

Address Sexual Health Needs of All Congregants

Church-based HIV prevention for MSM was positioned within a broader spectrum of health promotion. Accordingly, participants noted that sexual health was one component of total health and well-being that should be discussed within congregations. One participant pointed out the irony of churches that provided care to the dying, but failed to promote disease prevention when he stated, “Don't wait for us to get sick and then say, "Go to the hospital!” Others agreed that prevention efforts should be as important in churches as recovery and healing of the sick. All participants believed that sexual health promotion, including HIV prevention, should be both universal (i.e., for the entire congregation) and targeted (i.e., YBMSM-specific).

Universal Sexual Health Promotion

Universal sexual health promotion, defined as meeting the sexual health needs of all congregants, was one way to have inclusive HIV prevention efforts. Participants argued that most congregants would eventually become sexually active. Therefore, all congregants, regardless of sexual preferences, would struggle with issues related to sex. Instead of stigmatizing sex, participants offered an alternative: speak from experience and provide strategies to handle everyday temptations. Participants suggested that churches provide “sex positive’ education about topics such as birth control, correct condom use, healthy relationship techniques, and HIV testing. Other participants identified several common scenarios whereby pastors may be able to provide guidance and support for sexual health topics.

Preach a sex positive message. Lead by example. I'm not talking about every time I see you, should have a condom on your left eye, I’m talking about safe sex… I want to hear your experience. How did you deal with demons when your wife was in the pew trying to have sex with you but y'all wasn't married? How did you deal with your urges when you wanted to cheat? How did you deal with masturbation? These are things I want to hear from my pastor. – 25 year old, regular attendee, ID #03

A creation of something, a milestone, a new step for the church where we're supporting this in every church, not just the churches on the East that may show a high frequency of African Americans, who are gay. All churches, universal, like Obama did with healthcare. When you make it universal, no one feels left out, whether they're getting it or not. They know it's available for them. – 21 year old, regular attendee, ID #12

They [Black churches and their leaders] should put some type of effort into showing that they care about your health. …We all know that if a girl comes to church, you know she's not married, but she's 16-years-old and she's pregnant. You already know she's having sex. They should talk more about it. – 24 year old, regular church attendee, ID #18

Pastors were seen as a primary vehicle for this message, but not the only messenger. For many, it was important for the senior pastor to specifically address sexual health and HIV in sermons and suggested catch phrases such as “safe sex is great sex.” This authorization, they believed, would allow other ministries to address the topics more freely. A range of opportunities were suggested for other congregants to be involved. For example, two participants offered,

Speak on it, and make it a part of a sermon or a lesson in Bible study or Bible school. Make it their daily routine to inform youth and young adults about being aware of these things. – 25 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #01

They [Black churches] need to open their doors up to the health department and be like, we want to do more activities. Like the pool party, a picnic, a family gathering or friends trip. Anything. – 23 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #17

Forging partnerships with other public health entities was frequently discussed as a way to integrate sexual health messages into a church’s existing infrastructure. In particular, numerous respondents pointed out that people should be encouraged and taught how to consistently use condoms correctly. Condom discussions were essential, but condom distribution was also deemed important. Participants suggested that churches have a designated, but non-stigmatized location where people can obtain condoms, or goody bags with educational brochures, condoms and lubricant.

They could just talk about safe sex really. Like a health class. Just talk about it; talk about the consequences that can happen when you do something without a condom. Most people say, "It's just one time," but in that one time something can happen. – 19 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #06

People [have] to get out of their personal holdups and remember that they're here to help people, and not for their personal life. Church people [have] to realize that sex is not the devil. You can talk about it. It's OK to talk about it. It doesn't make you a bad person to be open about sex. – 25 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #30

Creating a safe space for sexual health questions and discussions was regarded as “the least you [churches] could do” to promote healthy sexual health among their congregants. Furthermore, participants viewed the proactive messaging was more important than the format and details of sexual health education, which adds an element of flexibility to the efforts churches can offer.

Targeted Sexual Health Promotion

In addition to the suggestions provided to churches to address the sexual health of all congregants, participants provided suggestions for churches to specifically address HIV prevention among YBMSM. Targeted sexual health promotion referred to the development of groups and services that were tailored to meet the needs of YBMSM. Nearly all participants expressed the need for a support group for YBMSM, many of whom may feel isolated or confused.

A support group is all that church really needs. Especially an African American church, because they're the ones, they will shun you as fast as popcorn… Everybody doesn't need to know everybody's business, but if you are in the church and you are struggling with being on the low or being a gay male and you don't know how to deal with it, you can have a support team – 22 year old, regular attendee, ID #05

Some participants also pointed out that holding MSM support groups in churches would also provide a platform for faith leaders to listen to the issues of MSM to better help them address their needs. Three participants noted,

I wasn't aware of things. My parents didn't tell me. Church didn't tell me. You got to start somewhere. Let me help you help me. – 24 year old, regular attendee, ID #02

Open the doors to the gay community. Make them want to come. One Sunday of the year, or of the month, dedicate the day to homosexuals, and/or a message to them, or let's plan out…what is it? A revival for homosexuals, to give that message, to make them use condoms, treatment if they have an STD. – 23 year old, infrequent attendee, ID #17

I feel like if a church throws things like the pastor teaching a health class for gays, it'd really wow the gay community. – 23 year old, regular attendee, ID #19

Thus, participants view church-based support groups a safe place for YBMSM to both offer and receive counsel.

Participants also recommended that churches be better equipped to connect YBMSM to HIV prevention, testing, and care services, since they are at an elevated risk of contracting HIV. Consistently, respondents believed faith leaders and Black churches could play a role in reducing the gaps in the HIV continuum of care for YBMSM. As explained by one participant,

Let's talk about how you can make a change in someone's life, as far as sending them to Chase Brexton [comprehensive health care clinic in Baltimore, MD]. I'm pretty sure all these pastors know an outreach or resource program that these people can go to. – 25 year old, regular attendee ID #07

As implied above, pastors who are also informed about HIV resources have the potential to improve engagement in care and outcomes of people who are at risk or living with HIV.

Participants also repeatedly advocated for the HIV counseling and testing to be available at church-sponsored events, not just health fairs or National HIV/AIDS Day activities. Offering HIV testing at church picnics, pools parties, block parties, or barbeques and other church-wide events would serve a dual purpose. On one hand, they could serve as acts of support and acceptance toward the MSM community. On the other hand, participants noted that church-wide events provide a perfect platform to support anonymous HIV testing and education. One participant linked HIV testing specifically to religion and God’s desire for people to be healthy,

Like I said, we have whatever services available to you as far as testing and all that stuff. Churches are godly places. God wants us to be healthy. – 21 year old infrequent church attendee, ID #11

Participants acknowledged that churches often reach a wide demographic audience. Thus, youth and individuals whose sexual identity is kept private could attend and enjoy such events, while anonymously taking advantage of the sexual health outreach. More importantly, it allows the entire congregation to be engaged and involved in the promotion of health of all its members.

Discussion

This study was designed to identify strategies that could yield more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts. Our findings demonstrated that YBMSM viewed churches as a potential source for HIV prevention. Our study findings suggest that reducing homosexuality stigma within Black churches may help to reduce HIV transmission within the YBMSM community. Open dialogue within churches may increase HIV knowledge and improve access to social support for prevention and care. Study findings also echo the need for churches to integrate sexual health into the discussion of total health (Williams, Pichon, Latkin & Davey-Rothwell, 2014), both for YBMSM and other congregants. Ultimately, our results support a tiered approached to providing more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts.

Homosexuality stigma is one of the common challenges of HIV prevention efforts for YBMSM (Sullivan, et al. 2012). In the current study, homosexuality stigma reduction was viewed as an integral part of HIV prevention in churches. Consistent with previous research by Bluthenthal and colleagues (2012), participants acknowledged the complexity of confronting organizational and cultural values that may be in direct conflict with HIV prevention efforts. Despite the anticipated difficulty of overcoming deeply held religious beliefs about homosexuality, nearly all participants believed that more respectful treatment of YBMSM would foster more inclusive church-based HIV prevention efforts. Participants suggested that faith leaders have an opportunity to address homosexuality stigma by encouraging congregants not to judge others and emphasizing the importance of coming together as a diverse community to promote social change. Unfortunately, many faith leaders may not have been adequately trained to address the range of issues associated with sex and sexuality. As a result, some clergy will continue to conceptualize homosexuality as deviant and immoral behavior (Ward, 2005), while other clergy welcome Black MSM to leadership roles including deacons, ushers, and committee members (Douglas, 1999; Woodyard et al., 2000).

Our findings suggest that churches might benefit from having a range of sexual health promotion options to consider, which situates prevention as part of an overall continuum of care. On one end of the spectrum, HIV prevention materials and events can be offered through partnerships with churches and public health professionals (e.g., Derose et al, 2011; Lindley Coleman, Gaddist, & White, 2010; Williams, Griffith, Pichon & Campbell, 2011). This approach allows for all congregants to benefit from the increased exposure to HIV and sexual health materials. On the other end of the spectrum, faith leaders and congregants could actively advocate for stigma and risk reduction by having YBMSM speak from the pulpit about their experiences of stigma and prejudice (Winder, 2015). This tiered approach aligns with the Gordon’s (1983) classification system of prevention (e.g., universal, selected, and indicated), which reflect the needs of diverse subgroups that present different levels of risk. As suggested by participants, expanding the focus of ministry meetings, may also facilitate sustainability because this approach allows the entire congregation, not just the faith leaders, to participate and be accountable for the outcomes. Thus, faith leaders can engage in HIV prevention efforts that best suit their congregations.

Strengths and Limitations

Study findings should be considered within the contexts of several limitations. First, the small sample size of this qualitative study limits the generalizability of the findings to other geographic locations and age groups. Second, selection bias may have impacted study results; men who were willing to participate in this research may have been different from those who chose not to participate in ways that cannot be examined with our data. In addition, we did not obtain data on sexual orientation. It is likely that there was diversity in the ways in which participants identified themselves, which in turn may have influenced their responses. Finally, we did not collect data from faith leaders or family members of YBMSM. The lack of other voices reduces our ability to accurately assess whether the strategies for more inclusive HIV prevention in Black churches would be feasible, even if they are acceptable among YBMSM.

Despite these limitations, this study makes important contributions to the literature. First, this is one of the first studies to obtain the perspectives of YBMSM on concrete strategies to develop more inclusive HIV prevention effort in Black churches. Having both regular and infrequent church attendees in the sample suggests that the strategies for more inclusive HIV prevention efforts in churches would be acceptable to YBMSM regardless of their level of church involvement. Second, our findings offer a compelling contrast to the research with non-YBMSM samples that suggested non-heterosexual identities should be kept private within churches (Barnes, 2013; Wilson, Wittlin, Muñoz-Laboy & Parker, 2011). Our participants not only suggested additional openness around sexuality, but also offered a menu of options on how churches might address such issues. Finally, our qualitative findings contribute to the ongoing efforts to identify culturally sensitive HIV prevention approaches for YBMSM. Specifically, our findings lay the foundation for the development, implementation and testing of church-based HIV prevention programs that are acceptable and feasible to YBMSM. Future interventions would likely benefit from addressing issues specifically related to YBMSM experiences in churches and recommendations for church-based HIV prevention.

Conclusions

Black churches have the potential to reach, support, and provide services to YBMSM. Findings from the current study suggest that Black churches can be a critical access point for YBMSM and represent an important setting to intervene for HIV prevention. Strategies to reduce homosexuality stigma and address sexual health needs among congregants were offered as ways to offer more inclusive HIV prevention efforts within churches. It is crucial that we identify, understand, and address homosexuality stigma and the tensions that exist within Black churches as we consider comprehensive HIV prevention in these settings. Future researchers might consider partnering with churches to develop HIV prevention programs that focus on the determinants of HIV risk that place all individuals, not just YBMSM, at risk for contracting the virus. Additional research is also needed to fully understand the extent to which the described recommendations can reduce the spread of HIV among YBMSM.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all of the young men who participated in this research, as well as Shayna Lans and Rebecca Udokop for their assistance with data collection. This work was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grants# R01 DA031030 and 3R01 DA031030-02S2) and the Johns Hopkins Center for AIDS Research (1P30AI094189).

References

- Agate LL, Cato-Watson D, Mullins JM, Scott GS, Rolle V, Markland M, Roach DL. Churches United to Stop HIV (CUSH): a faith-based HIV prevention initiative. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(Suppl. 7):60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman D, Aggleton P, Williams M, Kong T, Reddy V, Harrad D, Reis T, Parker R. Men who have sex with men: Stigma and discrimination. The Lancet. 2012;380:439–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: how community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(12):730–737. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore Commission on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment . Moving Forward — Baltimore City HIV/AIDS Strategy 2011. InterGroup Services; Baltimore, MD: Sep, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SL. To Welcome or Affirm: Black Clergy Views About Homosexuality, Inclusivity, and Church Leadership. Journal of Homosexuality. 2013;60(10):1409–1433. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2013.819204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley-Patton J, Bowe-Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A, Hawes S, Moore E, Williams E, Goggin K. Taking it to the pews: A CBPR-guided HIV awareness and screening project with black churches. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2010;22(3):218. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthenthal RN, Palar K, Mendel P, Kanouse DE, Corbin DE, Pitkin Derose P. Attitudes and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS in urban religious congregations: Barriers and opportunities for HIV related interventions. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(10):1520–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buseh AG, Stevens PE, McManus P, Addison RJ, Morgan S, Millon-Underwood S. Challenges and opportunities for HIV prevention and care: Insights from focus groups of HIV-infected African American men. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;17(4):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV among African American Gay and Bisexual Men. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Han CS, Paul J, Ayala G. Strategies of managing racism and homophobia among US ethnic and racial minority men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(2):145. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts RN, Parks CW. Religious involvement among black men self-labeling as gay. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2009;21(2–3):232–246. [Google Scholar]

- Derose KP, Mendel PJ, Palar K, Kanouse DE, Bluthenthal RN, Castaneda LW, Corbin DE, Domínguez BX, Hawes-Dawson J, Mata MA, et al. Religious congregations’ involvement in HIV: A case study approach. AIDS Behavior. 2011;15:1220–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9827-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas KB. Sexuality and the black church. Orbis Books; Maryknoll, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Foster ML, Arnold E, Rebchook G, Kegeles SM. ‘It's my inner strength’: spirituality, religion and HIV in the lives of young African American men who have sex with men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(9):1103–1117. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.600460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SA, Liverpool J. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. Journal of Religion and Health. 2009;48:6–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German D, Sifakis F, Maulsby C, Towe VL, Flynn CP, Latkin CA, Holtgrave DR. Persistently high prevalence and unrecognized HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Baltimore: the BESURE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2011;57(1):77–87. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318211b41e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RS., Jr An operational classification of disease prevention. Public Health Reports. 1983;98(2):107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Campbell B, Allen JO, Robinson KJ, Stewart SK. YOUR Blessed Health: an HIV-prevention program bridging faith and public health communities. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(Suppl 1):4–11. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haile R, Padilla M, Parker E. Stuck in the quagmire of an HIV ghetto: The meaning of stigma in the lives of older black gay and bisexual men living in New York City. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(4):429–42. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.537769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AC. Marginalization by the marginalized: race, homophobia, heterosexism, and “ the problem of the 21st century”. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 2009;21(4):430–448. [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Phillips G, Jones KC, Outlaw AY, Fields SD, Smith JC, The YMSM of Color SPNS Initiative Study Group Racial and sexual identity-related maltreatment among minority YMSM: prevalence, perceptions, and the association with emotional distress. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2011;25(S1):S39–S45. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill WA, McNeely C. HIV/AIDS disparity between African-American and Caucasian men who have sex with men: intervention strategies for the black church. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52(2):475–487. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9496-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Reports. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies WL, Dodge B, Sandfort TGM. Religion and spirituality among bisexual Black men in the USA. Cultur,e Health, & Sexuality. 2008;10(5):463–477. doi: 10.1080/13691050701877526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffries WL, Marks G, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Millett GA. Homophobia is associated with sexual behavior that increases risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV infection among black men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1442–1453. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0189-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindley LL, Coleman JD, Gaddist BW, White J. Informing faith-based HIV/AIDS interventions: HIV-related knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes at Project F.A.I.T.H. churches in South Carolina. Public Health Reports. 2010;125:12–20. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles RP, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2nd Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL., Jr Legacy denied: African American gay men, AIDS, and the black church. Social Work and Society. 2007;25(1):51–61. doi: 10.1093/sw/52.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL, Wilson PA, Remis RS. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Newcomb ME, Du Bois SN, Garcia SC, Grov C. HIV in young men who have sex with men: a review of epidemiology, risk and protective factors, and interventions. Journal of sex Research. 2011;48(2-3):218–253. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.558645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A, Cornwall A, Chute N, Sanders J, Thomas G, James G, Flanigan T. Keeping the faith: African American faith leaders’ perspectives and recommendations for reducing racial disparities in HIV/AIDS infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pichon LC, Powell TW. Review of HIV Testing Efforts in Historically Black Churches. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12:6016–6026. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120606016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon LC, Williams TT, Campbell BC. An Exploration of faith leaders’ beliefs concerning HIV prevention – 30 years into the epidemic. Family and Community Health. 2013;36(3):260–268. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318292eb10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt RN. “Still looking for my Jonathan”: Gay black men’s management of religious and sexual identity conflicts. Journal of Homosexuality. 2010;57(1):39–53. doi: 10.1080/00918360903285566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, Hall HI. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, –. PloS one. 2011;6(8):e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Kelly JA. The role of the Black Church in the lives of young Black men who have sex with men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2015:1–14. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1091509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe J, Doty N, Hawkins LA, Gaskins CS, Beidas R, Rudy BJ. Stigma and sexual health risk in HIV-positive African American young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2010;24(8):493–499. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, Simmons E, Mayer KH. HIV/AIDS and the Black church: What are the barriers to prevention services? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:1682–1685. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JM. Implementation of Evidence-Based HIV Interventions for Young Adult African American Women in Church Settings. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2014;43(5):655–663. doi: 10.1111/1552-6909.12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber J, Meyer I, Link B. Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(3):351–357. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Carballo-Diéguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, Sanchez J. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. The Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toma JD. Approaching rigor in applied qualitative research. In: Conrad CF, Serlin RC, editors. The Sage handbook for research in education: Engaging ideas and enriching inquiry. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. pp. 405–424. [Google Scholar]

- Valera P, Taylor T. Hating the sin but not the sinner• : A study about heterosexism and religious experiences among southern Black men. Journal of Black Studies. 2011;42:106–122. doi: 10.1177/0021934709356385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JNJ, Longmire-Avital B. The impact of religious faith and internalized homonegativity on resiliency for black lesbian, gay, and bisexual emerging adults. Developmental Psychology. 2013;49(9):1723. doi: 10.1037/a0031059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EG. Homophobia, hypermasculinity and the US black church. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(5):493–504. doi: 10.1080/13691050500151248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks FH, Powell TW, Illangasekare S, Rice E, Wilson J, Hickman D, Blum RW. Bringing evidence-based sexual health Programs to adolescents in Black churches: Applying knowledge from systematic adaptation frameworks. Health Education & Behavior. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1090198116633459. DOI: 10.1177/1090198116633459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MV, Palar K, Derose KP. Congregation-based programs to address HIV/AIDS: elements of successful implementation. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(3):517–532. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9526-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TT, Griffith DM, Pichon LC, Campbell B, Allen JO, Sanchez JC. Involving faith-based organizations in adolescent HIV prevention. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2011;5(4):425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams TT, Pichon LC, Latkin CA, Davey-Rothwell M. Practicing what is preached: Congregational characteristics related to HIV testing behaviors and HIV discussions among Black women. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;42(3):365–378. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P. Addressing stigma: A blueprint for HIV/STD prevention and care outcomes for Black and Latino gay men. National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS and the National Coalition of STD Directors; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Wittlin NM, Muñoz-Laboy M, Parker R. Ideologies of Black churches in New York City and the public health crisis of HIV among Black men who have sex with men. Global Public Health. 2011;6(sup2):S227–S242. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.605068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winder TJ. “Shouting it out”: Religion and the development of Black gay identities. Qualitative Sociology. 2015;38(4):375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Robinson LR, Braxton ND, Er DL, Conner AC, Renfro TL, DiClemente RJ. Comparative effectiveness of a faith-based HIV intervention for African American women: Importance of enhancing religious social capital. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(12):2226–2233. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodyard JL, Peterson JL, Stokes JP. “Let us go into the house of the Lord”: Participation in African American churches among young African American men who have sex with men. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling. 2000;54(4):451–460. doi: 10.1177/002234090005400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]