Abstract

BACKGROUND

A cancer diagnosis during adolescence or young adulthood may negatively influence social well-being. The existing literature concerning the social well-being of adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer was reviewed to identify gaps in current research and highlight priority areas for future research.

METHODS

A systematic review of the scientific literature published in English from 2000 through 2014 was performed. Eligible studies included patients and survivors diagnosed between the ages of 15 to 39 years that reported on social well-being domains in the City of Hope Cancer Survivor Quality of Life Model. Each article was reviewed for relevance using a standardized template. A total of 253 potential articles were identified. After exclusions, a final sample of 26 articles identified domains of social well-being that are believed to be understudied among AYAs with cancer: 1) educational attainment, employment, and financial burden; 2) social relationships; and 3) supportive care. Articles were read in their entirety, single coded, and summarized according to domain.

RESULTS

AYAs with cancer report difficulties related to employment, educational attainment, and financial stability. They also report problems with the maintenance and development of peer and family relationships, intimate and marital relationships, and peer support. Supportive services are desired among AYAs. Few studies have reported results in reference to comparison samples or by cancer subtypes.

CONCLUSIONS

Future research studies on AYAs with cancer should prioritize the inclusion of underserved AYA populations, more heterogeneous cancer samples, and comparison groups to inform the development of supportive services. Priority areas for potential intervention include education and employment reintegration, and social support networks.

Keywords: adolescent and young adult, cancer, education, employment, social support

INTRODUCTION

Each year in the United States, nearly 70,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15 to 39 years are diagnosed with cancer.1 AYAs represent a unique and understudied cancer population, with needs and challenges that differ from those of children and adults with cancer. In 2005, the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group was developed to evaluate the clinical and research needs of this unique oncology population.2 As a next step, in 2012, the National Cancer Institute developed 5 working groups comprised of experts in AYA oncology to review the evidence, identify gaps, and provide research priorities.3 The charge of the Health-Related Quality of Life and Symptoms (HRQOL) working group was to evaluate evidence over the past decade regarding AYA HRQOL in 4 key areas: social, physical, psychological, and spiritual well-being.

A task force within the HRQOL working group was charged with identifying current evidence regarding the social well-being of AYA patients with cancer and survivors, guided by the City of Hope Cancer Survivor Quality of Life model.4 This model identifies 4 key areas of well-being in cancer survivorship: physical and symptoms, psychological, social, and spiritual. Our goal was to evaluate the single domain of social well-being for AYAs with cancer, focusing on employment, education, finances, and interpersonal relationships.5

Generally speaking, in economically developed countries around the world, young people between the ages of 15 to 39 years are finishing school, transitioning from their childhood homes, entering and establishing themselves in the work-force, forming intimate and long-term emotional and sexual relationships, and starting families. Within the 15-to-39-year age range, variation exists in key developmental tasks faced by AYAs (Table 1).6-11 For example, the older teenage years9 are characterized by living at home with parents, attending secondary school, the physical changes of puberty, and the formation of a social identity,6 whereas emerging adults (aged 18-25 years) are often in the process of leaving their childhood home, obtaining higher education, career training, and establishing social connections independent from childhood.9 The transition from emerging adulthood to young adulthood (typically aged 26-39 years) is not marked as definitively as the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood given the increased heterogeneity of vocational and relationship experiences for young adults. By their late 20s or early 30s, most young adults have entered into a phase of independence by creating financial self-sufficiency, accepting responsibility for their actions, developing personal beliefs separate from their parents, and establishing equal adult relationships with their parents.6

TABLE 1.

| Age | Significant Social Relationships | Specific Social Issues/Milestones Related to Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| Mid-adolescence: early teenage years: ≤18 y | School peers, role models, parents | • Interrupted social development and peer identification |

| • High school achievement and graduation interrupted | ||

| • Delayed transition to living independently from parents | ||

| Emerging adulthood: 18–25 y | Friends, school and work peers, parents | • Delays or gaps in higher education |

| • Work/employment interruptions | ||

| • Barriers to adequate health insurance coverage | ||

| • Hindered achievement or maintenance of financial independence from parents | ||

| Young adulthood: 26–39 y | Partners, family, friends, school and work peers | • Difficulty developing and/or maintaining intimate partner/spouse relationships |

| • Problems with sexual function | ||

| • Fertility problems that may impact decisions regarding parenthood | ||

| • Difficulty achieving/maintaining financial independence from parents | ||

| • Geographic distance from family |

Abbreviation: AYA, adolescents and young adult.

Regardless of age, cancer disrupts people's lives. For AYAs, cancer diagnosis, treatment, and subsequent late effects can be particularly disruptive to social maturation, a process by which young people develop self-views, social cognition, awareness, and emotional regulation that guides them throughout the remainder of their lives.12,13 Thus, cancer-related disruptions can have deleterious implications for the life-long health and well-being of AYAs. Cancer experiences during adolescence and young adulthood have been underevaluated and much of what is known about this age group has been extrapolated from studies of pediatric cancer survivors. Furthermore, the normative social development and emergent social issues that arise during childhood likely differ greatly from those arising in adolescence and young adulthood. Thus, the goal in this review was to report on studies that explicitly focused on patients and off-treatment survivors diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 39 years.

The objective of the current study was to conduct a systematic review of the current literature regarding social well-being and provide recommendations for future research. Our research questions included: 1) what are the unique challenges to maintaining social well-being for AYAs; 2) how does social well-being for AYAs with cancer compare with that of the general population of AYAs; and 3) what are future research priorities to maximize social well-being for AYAs with cancer?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), which is a guideline for the structure of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.14,15

Search Strategy

Using predefined keywords that were determined using a modified list of terms from the social domain of the City of Hope Cancer Survivor Quality of Life model (ie, family distress, roles and relationships, affection/sexual function, appearance, enjoyment, isolation, finances, and work),4 2 members of the research team (A.C.K. and E.E.K.) searched titles and abstracts on the PubMed, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO databases to derive initial lists of eligible articles. Keywords included: “adolescent,” “adolescence,” “young adult,” “adolescent and young adult,” “teenage,” “pediatric,” “childhood cancer survivor,” “cancer,” “survivor,” or “patient”; “health-related quality of life” or “quality of life”; and “social,” “interpersonal,” “relationship,” or “role.” Additional terms included “work,” “job,” “occupation,” “employ,” “employment,” “labor force,” “education,” or “school.” Filters included articles written in the English language between 2000 and 2014.

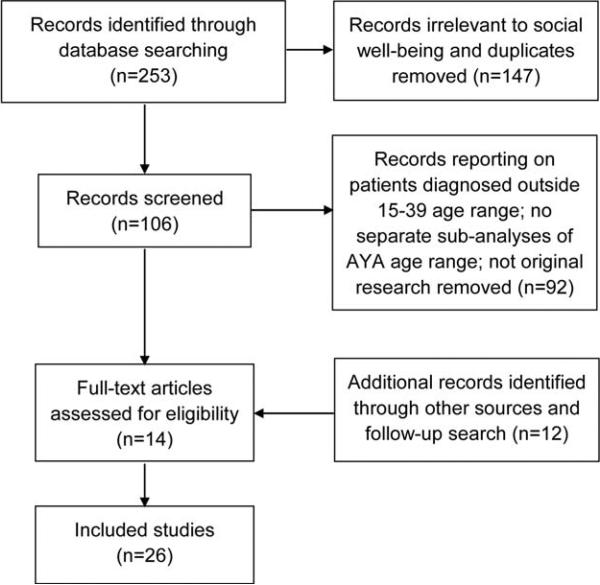

These searches yielded a total of 253 results (Fig. 1). All titles were reviewed manually by the authors, who had expertise in psychosocial care in AYA oncology. Articles irrelevant to social well-being outcomes and duplicates were removed at this stage, leaving a total of 106 potential articles for review. We excluded 92 articles because they focused on patients diagnosed outside of the age range of 15 to 39 years, had no separate subanalyses of AYA age range, and were not original research. A follow-up search using the same terms and methods was conducted in December 2014, yielding 2 additional results. In addition, 10 articles were included that were relevant to social well-being that did not appear in the search results, but were known to the workgroup due to their expertise in AYA cancer.

Figure 1.

Article inclusion and exclusion. AYA indicates adolescents and young adult.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible articles included those primarily focused on AYAs with cancer aged 15 to 39 years at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 1). We excluded articles that included subjects diagnosed with cancer outside of the age range of 15 to 39 years that did not analyze data from the AYA age range separately, allowing for flexibility of one year of age at diagnosis (14 years and 40 years). Four articles that did not report original research and 2 articles that did not focus on a social domain were excluded. We included four additional studies that: focused on a case report of AYA-aged subjects,16 included newly diagnosed patients ages 14–30,17 recruited individuals as young as age 12 years but only enrolled participants aged 13 to 15 years,18 and enrolled patients currently ages 13–29,19 as these studies included domains relevant to social well-being for AYAs.

Data Collection and Analysis

After article selection, the information from the final sample of articles was abstracted by 3 study team members (A.C.K., E.E.K., and E.L.W.) using a standardized template that included full citation, study design, sample size, age range at the time of diagnosis, recruitment site/source, data collection method, primary outcome measure/construct and instruments, and summary of key findings. Based on this template, the articles were reviewed for their relevance to AYA social outcomes. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Three domains addressed in the literature were identified: 1) educational attainment, employment, and financial burden; 2) social relationships; and 3) supportive care for social well-being. We report results by cancer type when available.

RESULTS

Twenty-six articles met eligibility for study inclusion and addressed the social domains of interest (ie, education, employment, financial burden, interpersonal relationships, and supportive care) (Table 2).16-41 The majority of studies were cross-sectional in design and used surveys or interviews for data collection. Six studies (23%) were primarily qualitative. Thirteen studies (50.0%) were hospital or clinic based, 12 studies (46%) were population-based or included multiple sites, and 3 studies (11.5%) involved Internet-based or community-based recruitment. A total of 24 studies (92%) recruited patients with heterogeneous cancer types, although few studies reported differences by cancer site.

TABLE 2.

AYA Social HRQOL: Review Articles (N = 26)

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Social Outcome Domaina | Age Range at Diagnosis, Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baerg 200316 | Case study | Hospital/clinic | 1 | 6–15 |

| Beale 200719 | Randomized trial | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 13–29b |

| Bellizzi 201220 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1, 2 | 15–39 |

| Carpentier 201121 | Qualitative interviews | Hospital/clinic | 2 | 18–34b |

| Dieluweit 201022 | Retrospective cohort surveys | Population | 2 | 15–18 |

| Geue 201423 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 3 | 15–39 |

| Goodall 201224 | Cross-sectional surveys | Hospital/clinic | 1, 3 | 15–32b |

| Grinyer 200725 | Qualitative interviews | Hospital/clinic | 1, 2 | 15–25 |

| Guy 201426 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1 | 15–39 |

| Keegan 201227 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 3 | 15–39 |

| Kent 201328 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1, 2 | 16–40 |

| Kent 201329 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 2, 3 | 15–39 |

| Kent 201230 | Qualitative focus groups, interviews | Clinic/other | 2 | 16–40 |

| Kirchhoff 201231 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1, 3 | 15–34 |

| Kirchhoff 201232 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 2 | 18–37 |

| Neal 200717 | Retrospective cohort | Hospital/clinic | 2, 3 | 14–30b |

| Olsen & Harder 200933 | Qualitative/mixed methods | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 15–22 |

| Parsons 201234 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1, 3 | 15–39 |

| Rabin 201335 | Qualitative interviews | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 18–39 |

| Smith 201336 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 3 | 15–39 |

| Smith 201337 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 2 | 15–39 |

| Stegenga & Ward-Smith 200818 | Qualitative interviews | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 13–15b |

| Tai 201238 | Cross-sectional surveys | Population | 1 | 15–29 |

| Valle 201339 | Randomized trial | Other | 3 | 18–39 |

| Zebrack 201340 | Cross-sectional surveys | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 14–39 |

| Zebrack 200641 | Delphi panel | Hospital/clinic | 3 | 15–39 |

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescents and young adult; HRQOL, health-related quality of life.

Social outcome domains include: 1) educational attainment, employment, and/or financial burden; 2) social relationships; and 3) supportive care.

Reported age at study.

Educational Attainment, Employment, and Financial Burden

In the United States, the National Cancer Institute-initiated Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) is to our knowledge one of few studies to investigate education and employment outcomes for AYAs. More than 72% of AYAs with cancer who had been full-time students or employees returned to school or work by 15 to 35 months after diagnosis.34 Patients who reported their cancer treatment was “very intensive” and those who had quit work/school after being diagnosed were more likely to report that cancer negatively affected their work/school after diagnosis, with >50% reporting problems with memory and attentiveness.34 On bivariate analyses, more patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia believed that cancer negatively impacted their work/education plans compared with AYAs with other cancers (ie, germ cell, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and sarcoma).34 Another AYA HOPE study indicated that 1 in 3 AYAs reported that cancer had a negative impact on their employment plans.20 This same study also indicated that younger AYAs (aged 15-20 years) reported a negative impact of cancer on their educational plans compared with those aged 21 to 29 years.20

Education

Studies comparing educational attainment among US samples of AYAs with cancer with controls typically demonstrated no differences,26,38 although to our knowledge there have been no analyses of educational outcomes that adjusted for demographic factors. Outside of the United States, there are also limited data. These few studies indicated that AYAs with cancer experience disrupted educational trajectories,25 and that AYAs, particularly males, indicate a need for assistance with returning to school/work.24 In qualitative interviews, cancer was described as a major disruption in the pursuit of educational opportunities due to absenteeism, inability to take required tests, and feeling as if they had been “left behind.”25 Educational settings are an important place for AYAs with cancer to develop supportive social networks. In a case study, one 15-year-old survivor of breast cancer felt proud and supported when she shared her cancer experience with a classmate.16

Employment

Employment limitations may be more common than deficits in educational attainment among AYAs with cancer.38 In one national US sample, 33.4% of AYAs with cancer versus 27.4% of controls were not working (P = .001).26 Of these, 34.1% of AYAs with cancer compared with 23.9% of controls were not working due to illness or disability. Similar issues with health-related unemployment were indicated in another US study, with 23.5% of AYAs with cancer compared with 13.7% of controls reporting unemployment due to health issues.38 In a qualitative study, AYA patients reported feeling “left behind” in their career or job trajectories compared with their peers.25 In this same study, AYAs who had previously pursued careers involving physical abilities believed that they needed to adjust their goals as a result of their cancer.25 In addition, some AYAs reported potential discrimination from employers due to their health problems,25 although the question of how common job-related discrimination is for AYAs with cancer remains unknown.

Financial burden and financial independence

Financial independence is often considered a hallmark of adulthood and AYAs with cancer experience financial difficulties. In a national study comparing individuals with and without cancer, AYAs reported lower family incomes compared with similar-age adults without cancer.26 In the same study, AYAs reported higher direct annual medical costs ($7417 vs $4247 for adults without a cancer history) and annual average lost productivity costs due to illness/disability of $2200 per year. In AYA HOPE, AYAs reported that cancer negatively impacted their financial situation, with 65% to 70% of AYAs aged 21 to 39 years and 51% of AYAs aged 15 to 20 years reporting a negative financial impact.20 In another study, AYAs with cancer who were in their 20s, female, and/or uninsured reported forgoing health care due to cost barriers, although no differences existed by diagnosis type.31 AYAs with cancer may need to rely on their parents for financial support, which can result in feelings of dependency and loss of control.25 Moreover, AYAs with lower socioeconomic status at the time of diagnosis are reported to have diminished HRQOL, with gradient effects such that each quintile of decreasing socioeconomic status is associated with worse HRQOL.28

Social Relationships

Peer and family relationships

Compared with the general AYA population, AYAs with cancer report greater challenges in social functioning.37 The effects of cancer on relationships with friends and peers, parents, siblings, and romantic partners may manifest in unique ways for AYAs with cancer compared with older or younger patients with cancer.30 In focus groups, AYAs with cancer who were between 6 months to 6 years from diagnosis reported needing support from peers and family and that they valued the opportunity to connect with other AYA patients through online networking and in-person peer support.30 In AYA HOPE, AYAs who reported that cancer had an impact on their close relationships were more likely to desire information regarding how to talk about their cancer with others. However, AYAs with acute lymphoblastic leukemia were less likely to indicate needing information about how to talk about their cancer experience compared to AYAs with other diagnoses.29

A German study indicated that AYAs with cancer have significantly poorer QOL scores, particularly for social and emotional function, in reference to a sex-matched and age-matched comparison cohort.23 AYA HOPE indicated that nearly one-half of AYAs believed their cancer negatively influenced their control over life.20 Male AYAs with cancer may be more likely to live with their parents compared with same-sex controls, although this was not the case for female AYAs.22 Patients with tumors of the central nervous system were more likely to live with their parents and less likely to be in long-term relationships compared with those with leukemia or lymphoma.22

AYAs with testicular cancer reported that their cancer made them feel “abnormal” compared with their peers, both physically and socially. They believed those who had not experienced testicular cancer did not understand how the experience had shaped their life views on “maturing and growing up,” giving them a unique, but different, outlook on life compared with their peers.21 In the same study, participants were reticent to disclose their cancer history to potential intimate partners and peers (eg, co-workers, friends) for fear this disclosure would diminish their masculinity.21 Feeling different from their peers is a source of stress for AYAs. In a series of in-depth qualitative interviews and written narratives with AYAs with cancer, participants reported experiencing stigma and unfair treatment from peers due to changes in their appearance, such as hair loss.25

Marital relationships

Marriage is another important social milestone for many AYAs, although to the best of our knowledge there is minimal research on this topic. In one national US study, fewer AYAs with cancer were currently married compared with similarly aged controls in adjusted analyses.32 AYAs with cancer were more likely to have divorced or separated than the controls. AYAs with cervical cancer were less likely to be married and more likely to be divorced or separated compared with controls and other AYAs with cancer. In addition, AYAs with ovarian cancer had a higher risk of being divorced or separated than controls, whereas AYAs with breast and testicular cancer had a decreased risk of divorce or separation compared with patients with other cancer diagnoses.32 The authors hypothesized that the emotional and financial burdens of cancer could lead to marital stress.32 The AYA HOPE study found that compared with married AYA patients with cancer, unmarried cancer survivors reported poorer mental health,37 and approximately 25% of AYA HOPE respondents reported that cancer negatively impacted their relationship with their spouse/significant other.20 AYAs with testicular cancer reported that their life perceptions and values, particularly their views on marriage and parenthood, changed during the course of their illness and treatment, with some reporting that they took these roles more seriously after their cancer than they would have before their diagnosis.21

Sexual functioning and intimacy

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have reported on sexual function and its relation with social well-being among AYAs with cancer. In AYA HOPE, greater than one-half of AYAs reported that cancer negatively impacted their body image.20 Survivors of testicular cancer reported that their cancer impacted their romantic and sexual relationships because they felt like “damaged goods” due to surgical scars and loss of a testicle.21 AYAs report fears about sexual attractiveness due to changes in their physical appearance resulting from their cancer (ie, hair loss, scarring, loss of body parts, etc), and their ability to have children.21,25

Supportive Care for Social Well-Being

Unmet needs related to social well-being

Studies in the United States, the Netherlands, and Australia have indicated that AYAs report a desire for more information regarding their cancer and treatment and want opportunities to ask questions, talk about their cancer, and process feelings.18,29,40 In AYA HOPE, unmet needs and treatment-related symptoms interfere with social activities, and those AYAs who are most likely to report unmet needs include men, those of nonwhite race/ethnicity, and those with physical/emotional health problems.27 AYAs with an unmet need (ie, financial support, mental health, support group) reported significantly poorer HRQOL and social functioning than those without an unmet need.36 AYAs report a lack of access to financial support for care31 and informational support for returning to work and school,34 and desire support in these areas more than spiritual support.24 In addition, AYAs and their providers may benefit from additional information concerning the efficacy of fertility preservation among young cancer survivors.17

Support groups

AYAs with cancer are interested in support groups.27 AYAs have expressed a desire to connect with other AYA patients with cancer and cancer survivors who may have experienced similar challenges talking about their cancer with friends and family.27,29,33 Zebrack et al surveyed AYAs with cancer and health care providers regarding supportive care needs and found that AYAs ranked opportunities to connect with peer survivors much more highly than did providers.41 For AYAs, building relationships with peer survivors may present pragmatic challenges that require innovative approaches,35 such as new uses of social media targeted to connect AYA survivors39 and other online resources such as forums, chat rooms, and blogs.35

Other interventions and programs

To the best of our knowledge, few studies to date have demonstrated effective strategies for social support for AYAs with cancer. One study investigated the feasibility of a nurse-led treatment intervention in a youth cancer clinic to strengthen patients’ social networks.33 AYAs embraced this social networking program, which consisted of a social network meeting (with patients, significant others, and important social network members), because they believed it helped them communicate their supportive needs, share the details of their diagnosis with important members of their social network, and maintain adequate social support.33 A case report indicated that AYAs may benefit from sharing expressive art therapy, such as poems or illustrations.16 Use of technology, such as video games, has been posited as a way for AYA patients to improve cancer knowledge.19 Also, AYAs may not be informed about the availability of services, including Internet sites, mental health services, and camps/retreats.40

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we identified few studies that examined social well-being among AYAs with cancer, despite the developmental complexity of this life stage. Herein, we outline specific recommendations for future research priorities with a focus on developing key measures for educational and employment deficits, the maintenance and development of social relationships, and the social support services needed to improve the social well-being of these individuals.

To our knowledge, there is a lack of research regarding the social experiences among AYAs with cancer compared with studies of older and younger patients, or in reference to comparison groups without a history of cancer. While the AYA HOPE study is the largest population-based US study to date on AYA patients, it does not include a control group and only includes patients with certain diagnoses. Future studies on AYAs with cancer should incorporate comparison samples from the same age range and samples that are more representative of sociocultural variations to provide additional perspectives on the effects of cancer on the social well-being of AYAs.

Based on the current literature, educational attainment for AYAs with cancer does not appear to differ from that of individuals with no history of cancer, although the studies we identified did not adjust for demographic differences and were often based on small samples. Nevertheless, many AYAs report unemployment or employment challenges due to cancer-related health problems, which is similar to reports on childhood survivors.42,43 Among AYAs and pediatric cancer survivors, more intense therapy is associated with unemployment in the long term.34,42 To our knowledge, it is unknown whether certain AYAs with cancer have problems managing late effects in the workplace or lack access to workplace accommodations. As such, we recommend additional research on educational attainment, the transition to employment, and work return after cancer treatment among AYAs, with an eye toward developing targeted interventions for high-risk groups.

Furthermore, the financial strain of treatment, from lost productivity and medical costs, continues for AYAs even after the end of their cancer therapy. This often leads to dependence on family members and financial concerns that adversely affect AYAs’ social relationships. With the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, AYAs with cancer may have better access to insurance coverage,44 thereby potentially alleviating some of their treatment-related financial burden, and this is an important area for study. The long-term financial effects for AYAs with cancer are unknown, but among childhood cancer survivors, >13% have at some time been enrolled on federal disability income coverage.45 Additional studies are needed to shed light on how cancer affects the financial status of AYAs with cancer throughout their lives.

Healthy peer relationships are a key component of late adolescence and young adulthood, and a cancer experience can have detrimental effects during this developmental stage, including a higher risk of social isolation, concerns with sexual intimacy, and relationship strain.32,46 AYAs with cancer report feeling isolated and missing out on important normative social activities (eg, school dances, sports) during their cancer treatment.47 Because most healthy AYAs have little familiarity with illness, peers may not recognize how to extend their support to a friend with cancer. However, to our knowledge, few social support programs have been tested among AYAs. A growing body of research has shown that AYAs with cancer are comfortable with and interact through multiple modes of in-person and Web-based information support.48,49 Future research in this area should examine interventions with social media and social networking tools to build peer-survivor relationships and improve social support for AYAs.39,50,51

Furthermore, AYAs with cancer experience continued challenges with sexual intimacy and strains on familial and partner relationships that are shown to vary by cancer site and sex. We suggest that subsequent studies explore the underlying reasons behind this variation to understand opportunities for resiliency and building supportive relationships after cancer, including evaluating the needs of male survivors who report difficulty with romantic partnerships and support.52 Overall, this review demonstrates the need to strengthen the evidence base that informs social advocacy and support of AYAs in developing new social contacts, achieving autonomy, and maintaining existing relationships.

We also recommend future research studies evaluate how geographic mobility affects AYAs facing cancer. AYAs often live far away from their family and many in this age group are unmarried. Distance issues could create logistical and tangible support problems and little is known regarding this issue. It is not clear how often AYAs with cancer return to live with family members during treatment or whether they rely on local peer support. In addition, we found few studies on sexual function and intimacy, which can lead to relationship challenges and uncertainties about parenthood,53 which are key areas for future research among AYAs with cancer.

There are certain limitations to the current review. Studies of AYAs with cancer have been very limited with regard to participant racial/ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. More inclusive samples are needed to inform the development of interventions and supportive services for the most vulnerable and underserved AYA cancer survivor populations. Future studies on AYAs should include clear reporting on factors such as age at diagnosis. We encourage researchers to conduct subgroup analyses among different age groups of AYAs, because many studies to date have included heterogeneous samples of pediatric, adolescent, and young adult cancer diagnoses.

Furthermore, to our knowledge, the majority of studies to date have not been designed to capture the potential heterogeneity in social well-being across cancer types. This is an important area because there may be high-risk diagnostic groups for poor social well-being that have not yet been identified. The limited research indicates there may be differences in education, employment, marital status, long-term relationships, and living situations by diagnosis type, with survivors of leukemia, central nervous system tumors, and female reproductive cancer at a higher risk. This suggests the need for more studies that evaluate differences by cancer types or that adjust for potential differences. In addition, the extent to which diagnosis type influences social well-being in other domains (eg, sexual functioning/intimacy, desire for support groups and other supportive services) merits further investigation. Last, it is possible that certain studies focused on the social well-being of AYAs were excluded for the following reasons: lack of citation in one of the search engines used, lack of information concerning age at the time of diagnosis, or the inclusion of participants outside the diagnosis age range of 15 to 39 years.

We found a need for comprehensive assessments of social well-being for AYA patients with cancer and survivors. The attributes of social well-being among AYAs with cancer are not well-defined nor consistently described in the literature. Despite a growing number of studies that indicate that AYAs with cancer desire additional support in maintaining and reintegrating into the workforce and educational programs, to our knowledge no interventions to date have addressed the need to support the transition of AYAs back to school and work. AYAs with cancer express a strong desire for social and emotional support through connections with peer networks. The use of social media and online social networking may be a potential avenue for supporting AYAs with cancer. To meet the needs of all AYAs, we recommend that future studies include a comprehensive range of ages at diagnosis in accordance with the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group report.2

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

Helen M. Parsons was supported by National Cancer Institute grant K07CA175063 for work performed as part of the current study.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health [July 2, 2015];A snapshot of adolescent and young adult cancers. http://nci.nih.gov/aboutnci/servingpeople/snapshots/AYA.pdf.

- 2.Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group . Closing the Gap: Research and Care Imperatives for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, LIVESTRONG Young Adult Alliance; Bethesda, MD: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AW, Seibel NL, Lewis DR, et al. Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: an update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer. 2015;X:000–000. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.City of Hope [March 30, 2015];Quality of life model applied to cancer survivors. http://prc.coh.org/pdf/cancer_survivor_QOL.pdf.

- 5.HealthyPeople.gov . Health-related quality of life and well-being. Healthy People; 2015. [May 1, 2015]. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/health-related-quality-of-life-well-being. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood: perspectives from adolescence through midlife. J Adult Dev. 2001;8:133–143. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eccles JS, Midgley C, Wigfield A, et al. Development during adolescence. The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. Am Psychol. 1993;48:90–101. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavaghan MP, Roach JE. Ego identity development of adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1987;12:203–213. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/12.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett JJ. Conceptions of the transition to adulthood among emerging adults in American ethnic groups. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;(100):63–75. doi: 10.1002/cd.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnett JJ, Galambos NL. Culture and conceptions of adulthood. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2003;(100):91–98. doi: 10.1002/cd.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Educational Psychology Interactive [July 2, 2015];Social development: why it is important and how to impact it. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/papers/socdev.pdf.

- 13.Nass SJ, Beaupin LK, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Identifying and addressing the needs of adolescents and young adults with cancer: summary of an Institute of Medicine workshop. Oncologist. 2015;20:186–195. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baerg S. “Sometimes there just aren't any words”: using expressive therapy with adolescents living with cancer. Can J Couns. 2003;37:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neal MS, Nagel K, Duckworth J, et al. Effectiveness of sperm banking in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a regional experience. Cancer. 2007;110:1125–1129. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stegenga K, Ward-Smith P. The adolescent perspective on participation in treatment decision making: a pilot study. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2008;25:112–117. doi: 10.1177/1043454208314515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beale IL, Kato PM, Marin-Bowling VM, Guthrie N, Cole SW. Improvement in cancer-related knowledge following use of a psycho-educational video game for adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellizzi KM, Smith A, Schmidt S, et al. Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience (AYA HOPE) Study Collaborative Group Positive and negative psychosocial impact of being diagnosed with cancer as an adolescent or young adult. Cancer. 2012;118:5155–5162. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpentier MY, Fortenberry JD, Ott MA, Brames MJ, Einhorn LH. Perceptions of masculinity and self-image in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: implications for romantic and sexual relationships. Psychooncology. 2011;20:738–745. doi: 10.1002/pon.1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dieluweit U, Debatin KM, Grabow D, et al. Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1277–1284. doi: 10.1002/pon.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geue K, Sender A, Schmidt R, et al. Gender-specific quality of life after cancer in young adulthood: a comparison with the general population. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1377–1386. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0559-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodall S, King M, Ewing J, Smith N, Kenny P. Preferences for support services among adolescents and young adults with cancer or a blood disorder: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy. 2012;107:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grinyer A. The biographical impact of teenage and adolescent cancer. Chronic Illn. 2007;3:265–277. doi: 10.1177/1742395307085335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guy GP, Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1024–1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keegan TH, Lichtensztajn DY, Kato I, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: a population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kent EE, Sender LS, Morris RA, et al. Multilevel socioeconomic effects on quality of life in adolescent and young adult survivors of leukemia and lymphoma. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1339–1351. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0254-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent E, Wilder-Smith A, Keegan TH, et al. Talking about cancer and meeting peer survivors: social information needs of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2013;2:44–52. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2012.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kent EE, Parry C, Montoya MJ, Sender LS, Morris RA, Anton-Culver H. “You're too young for this”: adolescent and young adults’ perspectives on cancer survivorship. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:260–279. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.644396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchhoff AC, Lyles CR, Fluchel M, Wright J, Leisenring W. Limitations in health care access and utilization among long-term survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5964–5972. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirchhoff AC, Yi J, Wright J, Warner EL, Smith KR. Marriage and divorce among young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0238-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen PR, Harder I. Keeping their world together-meanings and actions created through network-focused nursing in teenager and young adult cancer care. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:493–502. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b3857e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parsons HM, Harlan LC, Lynch CF, et al. Impact of cancer on work and education among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2393–2400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabin C, Simpson N, Morrow K, Pinto B. Intervention format and delivery preferences among young adult cancer survivors. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20:304–310. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AW, Parsons HM, Kent EE, et al. AYA HOPE Study Collaborative Group Unmet support service needs and health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer: the AYA HOPE Study. Front Oncol. 2013;8:75. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AW, Bellizzi KM, Keegan TH, et al. Health-related quality of life of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in the United States: the Adolescent and Young Adult Health Outcomes and Patient Experience Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2136–2145. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai E, Buchanan N, Townsend J, Fairley T, Moore A, Richardson LC. Health status of adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4884–4891. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, Allicock M, Cai J. A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Lattin B, et al. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201–214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zebrack B, Bleyer A, Albritton K, Medearis S, Tang J. Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer. 2006;107:2915–2923. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirchhoff AC, Leisenring W, Krull KR, et al. Unemployment among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Med Care. 2010;48:1015–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, van Dijk FJ. Adult survivors of childhood cancer and unemployment: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2006;107:1–11. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bleyer A, Ulrich C, Martin S. Young adults, cancer, health insurance, socioeconomic status, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cancer. 2012;118:6018–6021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kirchhoff AC, Parsons HM, Kuhlthau KA, et al. Supplemental security income and social security disability insurance coverage among long-term childhood cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv057. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, Neumark-Sztainer D. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence. 2007;42:265–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kameny RR, Bearison DJ. Cancer narratives of adolescents and young adults: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Child Health Care. 2002;31:143–173. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Love B, Donovan EE. Online friends, offline loved ones, and full-time media: young adult “mass personal” use of communication resources for informational and emotional support. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:241–246. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0579-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson CM, Crook B, Love B, Macpherson CF, Johnson R. Understanding how adolescents and young adults with cancer talk about needs in online and face-to-face support groups [published online ahead of print April 27, 2015]. J Health Psychol. doi: 10.1177/1359105315581515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cavallo DN, Chou WY, McQueen A, Ramirez A, Riley WT. Cancer prevention and control interventions using social media: user-generated approaches. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1953–1956. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Treadgold CL, Kuperberg A. Been there, done that, wrote the blog: the choices and challenges of supporting adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4842–4849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Love B, Thompson CM, Knapp J. The need to be Superman: the psychosocial support challenges of young men affected by cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2014;41:E21–E27. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.E21-E27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gorman JR, Bailey S, Pierce JP, Su HI. How do you feel about fertility and parenthood? The voices of young female cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:200–209. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0211-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]