Abstract

In an effort to devise a safer and more effective vaccine delivery system, outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) were engineered to have properties of intrinsically low endotoxicity sufficient for the delivery of foreign antigens. Our strategy involved mutational inactivation of the MsbB (LpxM) lipid A acyltransferase to generate OMVs of reduced endotoxicity from Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157:H7. The chromosomal tagging of a foreign FLAG epitope within an OmpA-fused protein was exploited to localize the FLAG epitope in the OMVs produced by the E. coli mutant having the defined msbB and the ompA::FLAG mutations. It was confirmed that the desired fusion protein (OmpA::FLAG) was expressed and destined to the outer membrane (OM) of the E. coli mutant from which the OMVs carrying OmpA::FLAG are released during growth. A luminal localization of the FLAG epitope within the OMVs was inferred from its differential immunoprecipitation and resistance to proteolytic degradation. Thus, by using genetic engineering-based approaches, the native OMVs were modified to have both intrinsically low endotoxicity and a foreign epitope tag to establish a platform technology for development of multifunctional vaccine delivery vehicles.

Keywords: OMV, E. coli O157, MsbB (LpxM), OmpA fusion, Vaccine vehicle

1. Introduction

OMVs are spherical lipid bilayer vesicles that are extruded naturally from the OM of Gram-negative bacteria [1]. The size of the membrane vesicles ranges from ~20–200 nm in diameter, and they are composed of characteristically antigenic OM constituents and some periplasmic contents, such as alkaline phosphatase and proteases, and even DNA and virulence factors [1,2]. Interestingly, a proteomic study showed that a number of cytoplasmic proteins also constituted the proteome of E. coli OMVs [3]. Thus, OMVs are nanosphere membrane vesicles having intrinsic properties to be a vaccine carrier possessing the native bacterial antigens, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Currently, a new paradigm for vaccine development has been emerging with non-replicating (acellular) vaccine delivery systems characterized by usage of nano/micro-particles, such as virus-like particles [4], liposomal vesicles such as proteoliposomes [5], archaeosomes prepared from the polar membrane lipids of Archaea [6], and virosomes composed of some viral envelope lipids [7]. In this respect, OMVs have notable advantages in vaccine development over other lipidic nanoparticles. The native OMVs have a multi-immunogenic capacity to carry a wide spectrum of endogenous antigens, in addition to the natural self-adjuvanticity that is exerted by toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, such as outer membrane proteins (OMPs), lipoproteins, and lipopolysaccharides (LPS). Beyond that, OMVs are generally superior in enhancing phagocytic uptake, as their surface molecules can be opsonized and/or recognized by the humoral immunity components. Furthermore, OMVs can also be modified by the inclusion of exogenous (synthetic) peptides and specific adjuvants, which will provide the possibility of utilizing the reconstituted OMV as anti-viral or anti-tumor therapeutic vaccines. Incorporation of additional functionality, such as fluorescent dye conjugation, to the surface components of OMVs could make them a more attractive biomaterial for vaccine delivery studies in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Proposed model for OMV production from genetically engineered E. coli O157:H7. The inactivation of MsbB activity and foreign epitope fusion to the OM-integral β-barrel domain of OmpA can generate OMVs composed of mainly penta-acylated LPS and the C-terminally truncated OmpA tagged with a foreign epitope, as illustrated.

In order to use these OMVs as vaccine delivery vehicles, safety issue has to be addressed because native OMVs are composed of fully endotoxic LPS, which provokes excessive secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in humans and animals [8]. In efforts to refine the OMV vector system to be applicable for vaccination, we employed mutational inactivation of the msbB gene encoding an acyltransferase catalyzing the final myristoylation step during lipid A biosynthesis [9,10]. It is known that the penta-acylated LPS produced from the msbB mutants shows reduced endotoxicity in human cells, compared with normal hexa-acyl lipid A producers [11,12]. In this regard, we hoped to exploit OMVs of low endotoxicity from an E. coli O157:H7 msbB mutant to establish their potential for vaccination.

We reasoned that incorporation of a foreign epitope into the OMV could be achieved by chromosomal tagging with DNA constructs containing the foreign epitope DNA conjoined with homologous DNA arms to be fused with ompA gene; the foreign epitope expressed with OmpA in fusion should be targeted to the OM to result in the spontaneous inclusion within the OMVs. If the foreign epitope in OMVs that have reduced endotoxicity could be generated in the msbB background harboring mainly penta-acylated LPS molecules, then these OMVs would be desirable vaccine delivery vehicles because the foreign epitope is physically linked to TLR agonistic adjuvants.

OmpA is one of the most abundant OM proteins in typical enteric Gram-negative bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella [13]. In addition to its abundance, the well-characterized two-domain structure of OmpA is advantageous to be fused with any sort of soluble foreign proteins. The crystal structure of OmpA showed that the N-terminal 171 residues adopt the β-barrel domain, which traverses the OM with eight anti-parallel β-sheet segments, exposing four external loops on the bacterial surface [14]. The remaining C-terminal portion of OmpA protein was shown to reside in the periplasm [14]. A truncated OmpA containing the N-terminal β-barrel domain but lacking as much as 132 amino acids from the periplasmic C-terminal domain was conferring the truncated OmpA insertion and the OM stability [15].

Accordingly, by construction of an OmpA fusion with the FLAG epitope as a model of the foreign epitope tagging in the OMV of the msbB mutant of E. coli O157:H7, we successfully modified OMVs intrinsically to be utilized as multifunctional vaccine delivery vehicles.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Creation of msbB mutants in E. coli O157:H7

E. coli O157:H7 strain Sakai [16] was used as parental strain for creation of gene-specific mutations by using one-step PCR mutagenesis method [17]. Accordingly, the parental E. coli stain was transformed with pKD46, a temperature-sensitive plasmid carrying the Red recombinase system from the λ bacteriophage under the control of the arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter. The Red recombinase system mediates the replacement of the target chromosomal sequence with an antibiotic resistance cassette obtained by PCR amplification using primers carrying homologies to the vicinity on the gene targeted for disruption. The O157 E. coli carrying pKD46 was transformed by electroporation with the PCR product generated from a PCR with the template plasmid pKD3 as described previously [17]. Transformants were plated in Luria–Bertani (LB) agar, containing the appropriate antibiotics (chloramphenicol (Cm) 10 μg/ml; ampicillin (Amp) 100 μg/ml), and mutants were confirmed by PCR and DNA sequence analysis.

As previously reported, E. coli O157:H7 strains possess two homologous msbB genes: a chromosomal msbB1 and a plasmid-encoded msbB2 gene [18]. In order to inactivate MsbB activity, the two msbB genes have to be disrupted at the same time. The sequential double msbB mutations have been achieved in E. coli O157:H7 by curing of pKD46 and introduction of pCP20, leading to site-specific excision of the integrated Cm cassette in either single msbB mutant (ΔmsbB1 or ΔmsbB2). Thus, the other msbB gene targeting followed up with each single msbB mutant, resulting in two separate mutants for the msbB1/msbB2 genes in the E. coli O157:H7. The resulting two mutants were designated Sakai-DM1 for the msbB1/msbB2 sequence and Sakai-DM2 for the msbB2/msbB1 sequence. Since there was no phenotypic variation between these two Sakai-DM mutants, Sakai-DM1 renamed as Sakai-DM (Supplementary Table 1) was chosen for further OMV production studies.

2.2. Construction of Sakai-DM mutants carrying the ompA::FLAG and pagP::FLAG fusions

As illustrated in Fig. 2A, intact ompA gene was cloned into pBlueScript-II SK vector to construct a template plasmid for the ompA::FLAG gene fusion assisted by the pKD46-encoding λ-Red recombinase. At first, a PCR amplicon called mega-primer DNA was obtained from the first PCR with the mutagenic reverse primer (called MutOmpA-Flag) designed to encode 2×FLAG sequence (DYKDHDG-DYKDHDDD) in the middle of the primer sequence carrying homologies to the C-terminal portion of the β-barrel domain of OmpA. Because a stop codon was incorporated into the end of the 2×FLAG-encoding primer sequence, the reading frame for the OmpA::FLAG has to be terminated after the processed N-terminal β-barrel domain of OmpA, thus lacking the C-terminal portion for the periplasmic domain. The first PCR product was then used as a mega-primer for the second step PCR to amplify the mutated allele containing the 2×FLAG sequence, thus resulting in the DNA encoding OmpA::FLAG fusion protein. Then, as selectable marker for the allelic replacement, the Cm cassette derived from pKD3 was placed in between the H2 and H3 homologies to the chromosomal DNA of E. coli O157:H7. The H2 and H3 regions in the mutagenic template DNA are meant to represent DNA sequence homologies to the target chromosomal DNA regions which would facilitate homologous recombination events. High-fidelity PCR was performed with a proofreading DNA polymerase (Advantage-HF2 PCR kit, BD Biosciences-Clontech, CA) as follows; denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 1 min, and elongation at 70 °C for 2 min. Transformants with the amplified allele were plated in LB agar, containing the Cm antibiotic, and the potential mutants were screened by PCR with a pair of Forw-1 and Rev-2 primers (Supplementary Table 1). Then, the resulting mutant (Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG) was confirmed by PsiI digestion and DNA sequencing of the amplicon obtained from PCR with Forw-1 and Rev-2 primers.

Fig. 2.

Recombinant DNA strategy (A) used to achieve the ompA::FLAG allelic replacement in the E. coli mutant (B). In panel A, a sequential PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis procedure was conducted by using the mutagenic mega-primer method. The Cm cassette (FRT–Cm–FRT) originated from the pKD3 plasmid and the H3 fragment corresponding to the downstream ompA gene was cloned into the template plasmid for the ompA gene targeting with the amplified DNA with Forw-1 and Rev-2 primers, as described in Materials and methods. In panel B, the potential mutant carrying the ompA::FLAG allele conjoined with the Cm-cassette (PCR products with Forw-1 and Rev-2 primers) was screened and confirmed by cleavage of the amplicon with PsiI that cuts the FLAG sequence specifically. Lanes M: size marker (1-kb ladder, Fermentas), 1: the amplified DNA for intact ompA from the parental strain, 2: the amplicon corresponding to the ompA::FLAG allele conjoined with the Cm-cassette in the mutant, and 3: the PsiI-digested amplicon from the mutant.

A similar allelic exchange strategy was employed in the generation of pagP::FLAG mutation in Sakai-DM mutant, with a view to producing strictly penta-acyl lipid A species by inactivation of PagP-mediated palmitoylation in the OM of Sakai-DM. In this case, pagP DNA region encoding the extracellular loop-1 was genetically manipulated to delete eight amino acid residues (YDKEKTDR) within the loop-1 of PagP and insert the FLAG sequence into the deleted region, so that the 8 residues of the PagP loop-1 can be in-framely replaced by the 2×FLAG residues. The previously described mega-primer PCR method by using a mutagenic reverse primer called MutPagP-Flag (Supplementary Table 1) was used for construction of the pagP::FLAG allelic template DNA. Then, the Cm-cassette and H3 homology fragment was placed in the downstream of the pagP::FLAG open reading frame. After the gene targeting, screening and confirmation of the mutants harboring the pagP::FLAG allele were conducted by the same way described in the ompA::FLAG mutation previously. The resulting mutant was characterized and named Sakai-DM/pagP::FLAG.

2.3. Preparation of OMVs

OMVs were prepared as described previously [19] with slight modifications. Briefly, E. coli O157:H7 and its isogenic mutants were inoculated into 500 ml of LB broth and cultured overnight at 37 °C shaker. The bacteria were then pelleted by centrifugation (11,000×g) for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was recovered and further passed through 0.22 μm pore-size filter. The OMVs were harvested from the filtered supernatant by precipitation using ammonium sulfate (390 g/l, final concentration). After the ammonium sulfate was added and completely dissolved, the mixture was left at 4 °C overnight to precipitate. Then, OMV was collected by centrifugation at 11,000×g for 30 min. The pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged again at 16,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C. OMVs remained in the supernatant were collected by centrifugation at 100,000×g for 2 h at 4 °C. The crude OMV-pellet obtained by the differential centrifugation was resuspended in 3 ml of PBS for further OMV purification by using sucrose-gradient ultracentrifugation step [3].

2.4. LPS preparation and SDS-PAGE analysis

LPS was prepared on a small scale from the whole-cell lysate method by using SDS-proteinase K treatment [20]. For LPS dry-weight determination, LPS isolated from each sample was extensively dialyzed against water, and the dialysate was lyophilized. Then, the lyophilized LPS was weighed on a balance. The LPS sample was dissolved in 2×SDS sample buffer, and boiled for 10 min prior to loading on a 16% Tricine SDS-PAGE gel (Novex, San Diego, CA). Then, the separated LPS bands were visualized by silver staining.

2.5. Analysis of radiolabeled lipid A by TLC

TLC experiments were performed to analyze the compositional variation of lipid A species isolated from the various mutants, as described previously [21]. The lipid A sample was dissolved in 100 μl of chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v), and 1,000 cpm of the sample was applied to the origin of a Silica Gel 60 TLC plate. TLC was conducted in a developing tank in the solvent chloroform/pyridine/88% formic acid/water (50:50:16:5, v/v). The plate was dried and visualized with an imaging analyzer (FLA-7000, FUJIFILM).

2.6. OMP profiles of the OM and OMV fractions

The OMPs of bacterial cells were prepared by a differential solubilization of total membrane proteins with N-lauroylsarcosine [22]. The total membrane fraction was resuspended in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5) containing 1% (wt/vol) sodium lauryl sarcosine, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min to dissolve the detergent-soluble cytoplasmic membrane fraction. Then, the sarcosine insoluble OM fraction was separated by centrifugation at 45,000×g for 90 min, and the OM pellet was washed twice with deionized water. The OMPs derived from the bacterial cells and the OMVs were then separated on a SDS–14% polyacrylamide gel and were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue G-250.

2.7. Western and dot blot analyses of the OMV fractions

Appropriate portion of the OMVs was analyzed by blotting onto nitrocellulose membrane (Invitrogen, USA). The mouse monoclonal antibody to FLAG epitope (Sigma, USA) and the peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Sigma, USA) were used for detection of the OmpA::FLAG-epitope protein in the OM and OMVs. The dilution ratios of both antibodies were 1:5000.

2.8. Electron microscopy

For OMV visualization by electron microscopy, OMVs were negatively stained and observed with a transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Briefly, A formvar-coated grid was floated on a droplet of sample on parafilm for 1 min to permit adsorption of the specimen. The grid was then transferred onto a drop of negative stain (1% uranyl acetate) for 30 s, blotted with a filter paper, and then air-dried. The sample was examined under CM20 transmission electron microscope (Philips, Netherlands). For visualization of OMV blebbing from the E. coli, the colonies grown overnight on LB plate at 37 °C were lifted and then fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde–glutaraldehyde mixture buffered with 0.1 M phosphate (pH 7.2) for 2h. The samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1h, dehydrated in graded ethanol and propylene oxide, and embedded in Epon-812. Ultra-thin sections, made by ULTRACUT E ultramicrotome (Leica, Austria), were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined under CM20 transmission electron microscope (Philips, Netherlands).

2.9. Endotoxicity (nuclear factor-κB induction) assay

The induction of NF-κB due to TLR4 activation by LPS stimulation was quantified using HEK-Blue™-4 cells (InvivoGen, USA). The LPS responding cells employed in this system are HEK293 cells stably transfected with TLR4, MD2, CD14, as well as secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) under the control of a promoter inducible by NF-κB, resulting that extracellular SEAP in the supernatant is proportional to NF-κB induction. HEK-Blue™-4 cells maintained in HEK-Blue™ selection medium containing zeocin and normocin, were incubated at a density of ~1×105 cells/ml in a volume of 180 μl/well, in 96-well flat-bottomed cell culture plate with the LPS stimuli, until confluency was achieved (20–24 h). Colorimetric assays for SEAP induction were measured using an AP-specific chromogen (QUANTI-Blue™) by spectrophotometer at 620 nm, as recommended in the vendor's instruction. All samples were run in triplicate, from which means and SD were determined.

2.10. Trypsinization and immunoprecipitation of OMVs

Trypsin was added to OMV (1 mg/ml in PBS) at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml and allowed to react for the indicated times at 37 °C. Digestion was stopped by addition of SDS sample buffer and immediate boiling of the digested sample for 5 min, prior to SDS-PAGE (14% gel) and western blot analyses with anti-OmpA and anti-FLAG antibodies.

For immunoprecipitation (IP), the purified OMVs and the OMV lysate prepared by rupturing the vesicles with sodium deoxycholate (final 1% solution) were resuspended in IP wash buffer (10 mM Tris/pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100), and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with 5 μg anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody or rabbit anti-OmpA polyclonal antibody with gentle rotation, respectively. Then, immune complexes formed in the reaction mixture were captured with protein G-agarose beads (pre-blocked with 1% BSA) by incubation overnight at 4 °C with gentle rotation. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation (2000×g, 1 min, 4 °C), washed three times with the IP wash buffer. After careful removal of the final wash, the pellet was resuspended in SDS sample buffer, and boiled for 5 min prior to SDS-PAGE and western analysis.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. MsbB-deficient mutant of E. coli O157:H7 and its derivatives

Since endotoxicity of LPS has long been recognized as an obstacle to the development of the LPS-containing vaccines, efforts have been made previously in finding ways of rendering the LPS molecules non-endotoxic. Inactivation of msbB in Gram-negative bacteria causes a marked reduction of LPS endotoxicity [23–25]. Accordingly, we created an E. coli MsbB-deficient mutant, which produces LPS consisting of the penta-acylated lipid A precursor [9–11]. The resulting MsbB-deficient mutant of E. coli O157 Sakai strain (Sakai-DM) was used as parental strain to introduce the defined ompA::FLAG and pagP::FLAG mutations, respectively, in the MsbB-deficient background.

The ompA::FLAG mutation was created in order to introduce the FLAG tag onto the OM and OMVs of the MsbB-deficient mutant. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the DNA sequence of a short peptide epitope can be incorporated in the mutagenic primer sequence, leading to an in-frame fusion with the target protein. However, when a larger protein domain needs to be incorporated, the H2 homology extension placed between the fusion site (bricks) and the Cm cassette (checker) can be entirely substituted with the cloned protein domain gene. In the case of FLAG tagging used in this study, a selectable restriction site (PsiI) was spontaneously introduced within the FLAG sequence, which allows easy screening of the potential mutants as exemplified in the confirmation of the PCR product for the ompA::FLAG amplified from the desired mutant (Fig. 2B).

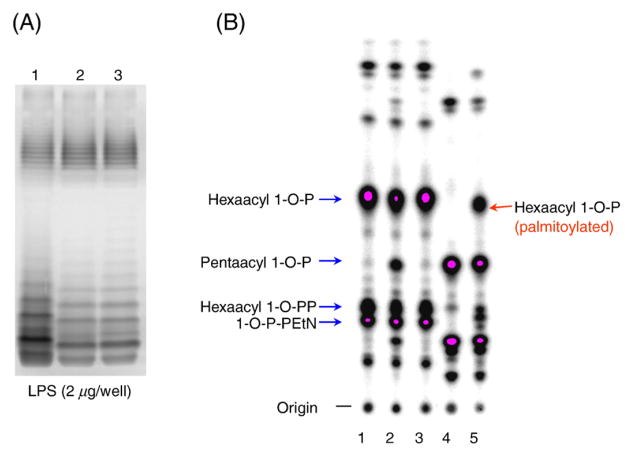

In the analysis of whole LPS molecules, no distinct change of LPS expression was noted except that the mainly penta-acylated LPS molecules migrate faster than the hexa-acylated LPS of wild type O157 Sakai (Fig. 3A). For analysis of the lipid A moiety, TLC experiments were conducted as described previously [27]. The major lipid A species in E. coli is phosphorylated at position-1, but lesser amounts can contain 1-diphosphoryl or 1-diphosphoryletha-nolamine moieties. The hexa-acylated 1-phosphoryl lipid A species disappeared completely only in the Sakai-DM/pagP::FLAG mutant (lane 4, Fig. 3B), demonstrating that the remaining palmitoylated (hexa-acyl) lipid A molecules in Sakai-DM (lane 5) were PagP-dependent [28]. Initially, the pagP::FLAG mutation was designed for inactivation of PagP by incorporation of a FLAG tag into the mutated loop-1 region of the protein so as to monitor the level of expression in the OM. We confirm that such an in-frame deletion of the eight (YDKEKTDR) residues in the catalytically active extracellular loop-1 region of PagP [26] can abolish the PagP-mediated palmitoylation of lipid A in Sakai-DM, giving rise to the strictly penta-acylated LPS in the msbB-deficient background. The assignments of lipid A species in Fig. 3B were based on the previous studies [27,28].

Fig. 3.

LPS (lipid A) profiles of the O157 E. coli mutants. The silver-stained LPS samples separated by SDS-PAGE are shown in panel A. Lanes 1: Sakai-WT, 2: Sakai-DM, 3: Sakai-DM/pagP::FLAG. In panel B, 32P-labelled lipid A species were separated by TLC and imaged. Note that the deficiency of both MsbB and PagP abolished the hexa-acylated lipid A (lane 4). Interestingly, there is a small fraction of penta-acylated lipid A species found in the Sakai-M1 (lane 2), in contrast to Sakai-WT (lane 1) and Sakai-M2 (lane 3). Although the palmitoylated (hexa-acyl) lipid A (lane 5) occurred in Sakai-DM, this MsbB-deficient mutant mainly produced penta-acyl (low-endotoxic) lipid As.

The penta-acylated lipid A species is known to be a much weaker agonist for the induction of proinflammatory cytokines through the TLR4–MD2 receptor complex [8,10]. In order to assess reduction of endotoxicity mediated by modified LPS isolated from the O157 mutants (Sakai-DM and Sakai-DM/pagP), we determined the level of NF-κB induction in the LPS treated HEK-Blue™-4 cells by measuring absorbance from the SEAP detection system. The modified LPS produced from the msbB mutant showed a significant reduction in the activation of NF-κB, compared to that of wild type (Fig. 4). These results from the in vitro assay suggest that OMVs harboring mainly penta-acylated lipid A species would display reduced endotoxicity compared to the native OMVs that possess hexa-acylated lipid A species. The difference of mean OD values in all 3 LPS samples was statistically significant when analyzed by one-way ANOVA (p-value<0.05).

Fig. 4.

Endotoxicity assessed by the level of NF-κB activation in the LPS treated HEK-Blue™-4 cells. The level of NF-κB induction was measured by using the SEAP detection system supplied with HEK-Blue™-4 cells (InvivoGen, USA) after treatment with the purified LPS samples from the O157 wild type and its mutants (Sakai-DM and Sakai-DM/pagP). The modified LPS of the msbB and msbB/pagP mutants showed a significant reduction in the activation of NF-κB, compared to that of wild type. The difference of mean OD values in the all 3 LPS samples was statistically significant when analyzed by one-way ANOVA (p-value<0.05).

3.2. TEM observations of OMVs

In electron microscopic observations (Fig. 5), OMVs of Sakai-DM derivatives were shown as nanosphere vesicles with variable sizes ranging from 40–100 nm in diameter. Crude OMVs (Fig. 5A) collected from the culture supernatant were purified by using sucrose-density gradient ultracentrifugation [3]. The purified OMVs pooled from the fractions 5 to 10 (Fig. 5C) gave a clear TEM image of OMVs (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, the msbB mutation increased the amounts of OMVs compared with wild type (data not shown), which might be due to the compromised OM permeability barrier observed in the MsbB-deficient mutant [18,28].

Fig. 5.

TEM observations of OMVs released from the O157 E. coli mutants. The OMVs in the culture supernatant (A) and the colonies (B) of Sakai-DM mutant were observed, respectively. OMV fractionation (C) by sucrose-density gradient ultracentrifugation was conducted with crude OMVs released from Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG mutant, and the pooled OMV fractions from 5 to 10 were shown (D).

3.3. Expression of the OmpA::FLAG fusion protein in the OM and OMVs

In the comparison of the OMP profiles (left panel, Fig. 6), unlike the Sakai wild type (lane 1) and Sakai-DM (lanes 2 and 4), the OM proteins of Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG (lanes 3 and 5) showed a distinctive OmpA truncation (lacking the 35 kDa band, but with a ~22 kDa band present); this observation is consistent with the designed C-terminal OmpA truncation and FLAG epitope (DYKDHDGDYKDHDDD) fusion conjoined with a stop codon between residues 174–175 of the OmpA protein. Western blot analysis (right panel, Fig. 6) demonstrated that the OmpA::FLAG protein was specifically detected by using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma, USA). These results suggest that the FLAG epitope fused to the β-barrel domain of OmpA can be expressed and successfully inserted into the OM without the remaining 151 residues of the C-terminal periplasmic domain of OmpA. Thus, the OmpA::FLAG protein was spontaneously incorporated into the OMVs when released during growth. Because OmpA is a structurally well-characterized and abundant OM protein, the foreign epitope fusion to the β-barrel domain of OmpA can be nicely utilized for tagging of OMVs with diverse foreign epitopes. Furthermore, OmpA has been known to have antigen carrier properties utilized for internalization of coupled foreign antigens by antigen-presenting cells and to prime CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), indicating that it can be a fusion target for exogenous antigen coupling to elicit therapeutic CTL responses [29].

Fig. 6.

Expression of the OmpA::FLAG in the OM and OMVs. The OmpA::FLAG protein was verified with the OM and OMVs samples by using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. The OmpA::FLAG protein (22 kDa bands, lanes 3 and 5) was only detected in the OM (lane 3) and the OMVs (lane 5) of Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG. Lanes 1: OMPs of Sakai-WT, 2 and 4: Sakai-DM, and 3 and 5: Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG.

3.4. Folding status of OmpA::FLAG protein

Because the electrophoretic mobility of the folded β-barrel membrane proteins on SDS-PAGE can differ from that of the fully denatured forms if the samples are not boiled prior to electrophoresis, this so-called “heat modifiability” of OMPs has become a standard assay for assessing OMP folding [35,36]. We exploited this phenomenon to provide evidence for the folding status of OmpA::FLAG, as a truncated form of OmpA, in the OM. Using this assay, we showed that the folded OmpA (no boiling) migrates faster than the unfolded (boiling) conformation (Fig. 7). Interestingly, however, the OmpA::FLAG in the OM showed a different migration pattern as opposed to that of intact OmpA, that is, the unfolded OmpA::FLAG (denatured by boiling) migrates faster than the folded β-conformation (Fig. 7). This kind of inverse shift has been reported in the case of PagP, which is an 8-stranded β-barrel OMP composed of 161-residues [37]. Collectively, these inverse shifts of heat modifiability suggest that the OmpA::FLAG is correctly folded as a β-barrel conformer (Fig. 8) in the OM and OMVs of the mutant.

Fig. 7.

Heat modifiability of intact and the truncated forms of OmpA proteins in SDS-PAGE. The folding of de novo-expressed OmpA::FLAG was assessed by heat modifiability in SDS-PAGE. Folded OmpA (~30 kDa band) migrates faster than the heat-unfolded conformation (35 kDa band) in SDS-PAGE (left panel). However, the heat-unfolded OmpA::FLAG (~22 kDa band) migrates faster than the folded β-conformation (right panel). This inverse shifting in the mobility of OmpA might be due to the C-terminal truncation in the OmpA:: FLAG, suggesting that the OmpA::FLAG is correctly folded as a β-barrel conformer in the OM.

Fig. 8.

Proposed topology for the OmpA::FLAG protein in the OM. The proposed OM topology of the integral OmpA::FLAG protein is shown. Since OmpA amino acid residues up to G-171 have been structurally characterized to comprise the N-terminal β-barrel domain [14], the C-terminally tagged FLAG peptide (shaded) to the 174th residue has to be located in the periplasmic side, thus the introduced foreign epitope can be spontaneously entrapped in the lumen of the OMVs. The inset shows that OMVs containing the OmpA::FLAG were specifically detected by dot blot analysis.

3.5. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and trypsinization of OMVs

IP and OMV trypsinization were carried out to provide evidences that the FLAG epitope fused C-terminally in truncated OmpA could be localized in the lumen of the OMVs containing the OmpA::FLAG; this luminal localization of a foreign antigen will protect it from proteolysis by host proteases when the OMV is given for host immunization by possible mucosal routes. In IP experiments, the OMVs treated with anti-OmpA antibodies were immunoprecipitated and, subsequently, the OMVs containing the OmpA::FLAG were specifically detected by western blotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody and compared with control OMVs containing intact OmpA (lane 1, Fig. 9B). When the OM and OMV lysates (Fig. 9A and C) were interrogated by anti-FLAG for IP and western blot, the OmpA::FLAG band was only detected in those lysates from Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG (lanes 2, Fig. 9A and C), compared with Sakai-DM control (lanes 1). Conversely, when intact OMVs were interrogated by IP and western blot with anti-FLAG antibody, there was no signal detected (data not shown). These results suggest that the FLAG epitope (foreign antigen) fused in the OmpA::FLAG was not localized on the surface of the OMVs.

Fig. 9.

Immunoprecipitation and trypsinization of OMVs. In IP experiments (A, B, and C), the OMVs treated with anti-OmpA antibodies were immunoprecipitated and, subsequently, the OMVscontainingthe OmpA::FLAG (lane 2 of panel B) were specifically detected by westernblotting with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibodyandcompared with control OMVs containingintact OmpA (lane 1 of panel B). When the OM (A) and OMV (C) lysates were interrogated by anti-FLAG for IP and western blot, the OmpA::FLAG band was only detected in those lysates from Sakai-DM/ompA::FLAG (lane 2, panel A), compared with Sakai-DM (lane 1, panel A). These results suggest that the FLAG epitope (foreign antigen) fused inthe OmpA::FLAG is localized inthe lumen of the OMVs. Panels D and E were western blots of trypsinized OMVs containing the OmpA::FLAG probed with anti-OmpA (D) and anti-FLAG (E) antibodies, respectively.

In the OMV trypsinization (panels D and E), the OmpA::FLAG proteins remained undigested after the specified time of trypsinization at 37 °C, suggesting that FLAG epitope fused to the OmpA β-barrel domain was not accessible to trypsin digestion because of the folding configuration of the OmpA::FLAG protein in the OMVs. Consistent with the folding of the OmpA::FLAG probed by heat modifiability (Fig. 7), these data indicate that the foreign epitope fused to the OmpA β-barrel domain can be incorporated into the OMVs with a luminal exposure that protects them from proteolytic digestion.

3.6. A model for foreign epitope tagging to OMVs is established

The foreign FLAG epitope fused to the β-barrel domain of OmpA can be localized to the periplasmic side of the OM when correctly folded. Subsequently, the foreign epitope can be spontaneously entrapped in the lumen of the OMVs (Figs. 1 and 8). Accordingly, the foreign epitope localized inside the OMV is protected from proteolysis (Fig. 9). This model for foreign epitope tagging to the OMVs by using the OmpA-fusion approach should be applicable to any sizable choice of soluble antigens, because the H2 homology extension (Fig. 2A) can be entirely replaced by the target gene encoding any antigenic protein to be fused for the induction of the antigen-specific immune responses by the delivery of the OMV/OmpA-carrier. OmpA shows diverse functions in adherence and invasion of host cells, and induces maturation of dendritic cells via signaling through TLR2 [29,30]. Those foreign proteins fused to OmpA are thus physically linked to strong adjuvants in the OMV vaccine vehicle.

Cattle infected by E. coli O157:H7 pose a constant threat to infect humans due to the consumption of contaminated beef [30,31]. To prevent the transmission of this pathogen from beef to humans, vaccination of cattle is considered as a promising approach to reduce intestinal colonization and shedding of this microorganism. In this regard, the FLAG-tagged OMVs from E. coli O157:H7 can be a vaccine candidate, not only for the induction of mucosal immunity, but also for allowing the differentiation of naturally-infected versus vaccinated animals because of the positive serology against the FLAG-tag, which could be used as a vaccination marker.

In the present study, we devised OmpA::FLAG-tagged OMVs in which the endogenous LPS molecules are composed primarily of the penta-acylated (much less-endotoxic) rather than hexa-acylated (fully endotoxic) lipid A moiety. By genetic manipulations E. coli O157:H7 mutants were created to transform their OMVs into an antigen delivery vehicle, which is a potential candidate for a safer, multi-immunogenic, and self-adjuvanted nanosphere vaccine vehicle. Recently, promising results have accumulated in experimental vaccination with some native OMVs from diverse pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria [32–34]. The strategy we have used for the OMV modifications in this study will be further applied to the development of multifunctional OMV vaccine delivery vehicles. Although inflammatory agonists other than lipid A are present in OMVs, reducing lipid A toxicity represents an important first step toward OMV detoxification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from KRIBB Research Initiative Program. Work in the laboratory of REB was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research operating grant MOP-84329. Anti-OmpA rabbit polyclonal antibody was a generous gift from T. Silhavy (Princeton University).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.001.

References

- 1.Beveridge TJ. Structures of Gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4725–4733. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.4725-4733.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuehn MJ, Kesty NC. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles and the host pathogen interaction. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2645–2655. doi: 10.1101/gad.1299905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee EY, Bang JY, Park GW, Choi DS, Kang JS, Kim HJ, Park KS, Lee JO, Kim YK, Kwon KH, Kim KP, Gho YS. Global proteomic profiling of native outer membrane vesicles derived from Escherichia coli. Proteomics. 2007;7:3143–3153. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casal JI, Rueda P, Hurtado A. Parvovirus-like particles as vaccine vectors. Methods. 1999;19:174–186. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parmar MM, Edwards K, Madden TD. Incorporation of bacterial membrane proteins into liposomes: factors influencing protein reconstitution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1421:77–90. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan L, Sad S, Patel GB, Sprott GD. Archaeosomes induce long-term CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response to entrapped soluble protein by the exogenous cytosolic pathway in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. J Immunol. 2000;165:5177–5185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amacker M, Engler O, Kammer AR, Vadrucci S, Oberholzer D, Cerny A, Zurbriggen R. Peptide-loaded chimeric influenza virosomes for efficient in vivo induction of cytotoxic T cells. Int Immunol. 2005;17:695–704. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raetz C, Whitfield C. Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:635–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clementz T, Zhou Z, Raetz CR. Function of the Escherichia coli msbB gene, a multicopy suppressor of htrB knockouts, in the acylation of lipid A. Acylation by MsbB follows laurate incorporation by HtrB. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10353–10360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somerville JE, Cassiano L, Jr, Darveau RP. Escherichia coli msbB gene as a virulence factor and a therapeutic target. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6583–6590. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6583-6590.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hajjar AM, Ernst RK, Tsai JH, Wilson CB, Miller SI. Human toll-like receptor 4 recognizes host-specific LPS modifications. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:354–359. doi: 10.1038/ni777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pautsch A, Schulz GE. Structure of the outer membrane protein A transmembrane domain. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1013–1017. doi: 10.1038/2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bremer E, Cole ST, Hindennach I, Henning U, Beck E, Kurz C, Schaller H. Export of a protein into the outer membrane of Escherichia coli K12. Stable incorporation of the OmpA protein requires less than 193 amino-terminal amino-acid residues. Eur J Biochem. 1982;122:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb05870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi T, Makino K, Ohnishi M, Kurokawa K, Ishii K, Yokoyama K, Han CG, Ohtsubo E, Nakayama K, Murata T, Tanaka M, Tobe T, Iida T, Takami H, Honda T, Sasakawa C, Ogasawara N, Yasunaga T, Kuhara S, Shiba T, Hattori M, Shinagawa H. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 2001;8:11–22. doi: 10.1093/dnares/8.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SH, Jia W, Bishop RE, Gyles C. An msbB homologue carried in plasmid pO157 encodes an acyltransferase involved in lipid A biosynthesis in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1174–1180. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.1174-1180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Post DMB, Zhang D, Eastvold JS, Teghanemt A, Gibson BW, Weiss JP. Biochemical and functional characterization of membrane blebs purified from Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:38383–38394. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508063200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hitchcock PJ, Brown TM. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:269–277. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.269-277.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Z, Lin S, Cotter RJ, Raetz CR. Lipid A modifications characteristic of Salmonella typhimurium are induced by NH4VO3 in Escherichia coli K12. Detection of 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, phosphoethanolamine and palmitate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18503–18514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown EA, Hardwidge PR. Biochemical characterization of the enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli LeoA protein. Microbiology. 2007;153:3776–3784. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/009084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somerville JE, Cassiano L, Jr, Bainbridge B, Cunningham MD, Darveau RP. A novel Escherichia coli lipid A mutant that produces an anti-inflammatory lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:359–365. doi: 10.1172/JCI118423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Ley P, Steeghs L, Hamstra HJ, ten Hove J, Zomer B, van Alphen L. Modification of lipid A biosynthesis in Neisseria meningitidis lpxL mutants: influence on lipopolysaccharide structure, toxicity, and adjuvant activity. Infect Immun. 2001;69:5981–5990. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.5981-5990.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalupahana R, Emilianus AR, Maskell D, Blacklaws B. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium expressing mutant lipid A with decreased endotoxicity causes maturation of murine dendritic cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:6132–6140. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6132-6140.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop RE. The lipid A palmitoyltransferase PagP: molecular mechanisms and role in bacterial pathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:900–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim SH, Jia W, Parreira VR, Bishop RE, Gyles CL. Phosphoethanolamine substitution in the lipid A of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its association with PmrC. Microbiology. 2006;152:657–666. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28692-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith AE, Kim SH, Liu F, Jia W, Vinogradov E, Gyles CL, Bishop RE. PagP activation in the outer membrane triggers R3 core oligosaccharide truncation in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4332–4343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708163200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeannin P, Bottazzi B, Sironi M, Doni A, Rusnati M, Presta M, Maina V, Magistrelli G, Haeuw JF, Hoeffel G, Thieblemont N, Corvaia N, Garlanda C, Delneste Y, Mantovani A. Complexity and complementarity of outer membrane protein A recognition by cellular and humoral innate immunity receptors. Immunity. 2005;22:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torres AG, Li Y, Tutt CB, Xin L, Eaves-Pyles T, Soong L. Outer membrane protein A of Escherichia coli O157:H7 stimulates dendritic cell activation. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2676–2685. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2676-2685.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torres AG, Kaper JB. Multiple elements controlling adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 to HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4985–4995. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.4985-4995.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alaniz RC, Deatherage BL, Lara JC, Cookson BT. Membrane vesicles are immunogenic facsimiles of Salmonella typhimurium that potently activate dendritic cells, prime B and T cell responses, and stimulate protective immunity in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:7692–7701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.11.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norheim G, Aase A, Caugant DA, Høiby EA, Fritzsønn E, Tangen T, Kristiansen P, Heggelund U, Rosenqvist E. Development and characterization of outer membrane vesicle vaccines against serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis. Vaccine. 2005;23:3762–3774. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schild S, Nelson EJ, Camilli A. Immunization with Vibrio cholerae outer membrane vesicles induces protective immunity in mice. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4554–4563. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00532-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ried G, Koebnik R, Hindennach I, Mutschler B, Henning U. Membrane topology and assembly of the outer membrane protein OmpA of Escherichia coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:127–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00280309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burgess NK, Dao TP, Stanley AM, Fleming KG. β-Barrel proteins that reside in the Escherichia coli outer membrane in vivo demonstrate varied folding behavior in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:26748–26758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802754200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huysmans GHM, Radford SE, Brockwell DJ, Baldwin SA. The N-terminal helix is a post-assembly clamp in the bacterial outer membrane protein PagP. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.