Abstract

Purpose

The authors conducted a systematic review of the medical literature to determine the factors most strongly associated with localizing primary care physicians (PCPs) in underserved urban and rural areas of the United States.

Method

In November 2015, the authors searched databases (MEDLINE, ERIC, SCOPUS) and Google Scholar to identify published peer-reviewed studies that focused on PCPs and reported practice location outcomes that included U.S. underserved urban or rural areas. Studies focusing on practice intentions, non-physicians, patient panel composition, or retention/turnover were excluded. They screened 4,130 titles and reviewed 284 full-text articles.

Results

Seventy-two observational or case-control studies met inclusion criteria. These were categorized into four broad themes aligned with prior literature: 19 studies focused on physician characteristics, 13 on financial factors, 20 on medical school curricula/programs, and 20 on graduate medical education (GME) programs. Studies found significant relationships between physician race/ethnicity and language and practice in underserved areas. Multiple studies demonstrated significant associations between financial factors (e.g., debt or incentives) and underserved or rural practice, independent of preexisting trainee characteristics. There was also evidence that medical school and GME programs were effective in training PCPs who locate in underserved areas.

Conclusions

Both financial incentives and special training programs could be used to support trainees with the personal characteristics associated with practicing in underserved or rural areas. Expanding and replicating medical school curricula and programs proven to produce clinicians who practice in underserved urban and rural areas should be a strategic investment for medical education and future research.

The shortage and geographic maldistribution of primary care physicians in underserved areas of the United States have been well described. Nearly 67 million Americans live in the 6,100 federally designated primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs), in which the full-time-equivalent primary care physician to population ratio exceeds 1 to 3,500.1,2 Although there are approximately 80 primary care physicians per 100,000 people in the United States, there are only 68 per 100,000 practicing in rural areas compared with 84 per 100,000 in urban areas.3 Similar shortages are found in urban underserved communities. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) estimates that an overall shortage of physicians due to workforce aging, population growth, and greater demand for health care services will range from 40,000 to 90,000 by 2025.4 If physicians continue to forego practicing in low-resource areas, worsening shortages of primary care physicians may exacerbate existing disparities in access to essential health care services.

Prior research has shown that higher concentrations of primary care physicians are independently associated with better health outcomes in multiple domains, including cancer, management of chronic disease, self-rated health, and overall mortality.5–10 However, the factors underlying choosing to practice in underserved areas have not been clearly delineated.11 A physician's personal characteristics, such as languages spoken, ethnicity, and prior experiences working with underserved populations, may influence his or her choice to train and work in a high-need area.12–16 Institutional factors, like participation in medical training programs emphasizing underserved rural and urban practice, exposure to federal programs incentivizing primary care specialty choice, and perceptions of careers in primary care, may play additional roles.17,18 For some physicians, post-training financial debt is a crucial determinant.19,20

Another important factor is the lack of substantial graduate medical education (GME) dollars in the underserved communities that hope to retain or attract primary care physicians. With this in mind, a recent Institute of Medicine report argued for the redistribution of funding for GME training programs from the traditional hospital setting alone to include various community settings, such as ambulatory care facilities, where the majority of health care is delivered.21One recent analysis showed that 56% of graduates of family medicine residencies practice within 100 miles of where they completed their training.22

Knowledge of the factors that influence physicians' choosing to practice in high-need areas is important to increasing the availability of primary care services in these areas. In this study, we review and analyze the medical literature to determine what factors are most strongly associated with localizing primary care physicians in underserved urban and rural areas in the United States.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of peer-reviewed studies that examined factors associated with primary care physician practice location in underserved urban and rural areas. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist as a guide for our data collection and analyses.23 The search was performed using the MEDLINE (via PubMed), ERIC, and SCOPUS databases, Google Scholar, and targeted hand-searching with reference mining. It was completed on November 5, 2015. Key words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were searched, including the following: primary care physicians (MeSH), medically underserved area (MeSH); practice location, primary care physician shortage; recruiting and primary care physicians; rural physicians; rural or inner city or urban and primary care; scholarship or loans and primary care; and minority groups (MeSH) or foreign medical graduate (MeSH) and professional practice location (MeSH). The same general search strategies were used for all information resources. (For full search strategies for each database, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 1]).

As no preexisting comprehensive review, that we are aware of, has examined predictors for the outcome of underserved urban practice location, we did not limit our search to specific dates. We included studies on the effect of medical school training programs on underserved rural practice location if they were published between 2007 and 2015--that is, after Rabinowitz et al's 2008 systematic review,24 whose references we manually screened. Newer studies that cited that 2008 review were also examined.

The search limits were set to include only English-language articles and abstracts. Our inclusion criteria were: (1) practice location outcomes were reported; (2) outcomes reported included underserved urban or rural practice area; (3) practice location outcomes were in the United States; (4) the focus was on primary care physicians; and (5) the study was peer reviewed. Studies that analyzed U.S. practice locations of international medical graduates (IMGs) were included. The exclusion criteria were: not peer reviewed, focus on non-physicians, case reports without methodology, outcomes reported only on intention to practice, outcomes focused only on characteristics of physician patient panels, or focus on retention and turnover.

We accepted the authors' definition of underserved urban and rural areas—primary care HPSA or Medically Underserved Area (MUA), a high percentage of poverty-level or low-income populations, a high percentage of ethnic minorities, a high percentage of the population with limited English proficiency (LEP), or safety net (rural health center, Indian Health Service, or community health center)—as determined by self-report or practice zip code, address, or census track.11 Three policy briefs indexed in the databases searched were reviewed for topical relevance and rigor,25–27 but published commentaries and opinion pieces were omitted. Related literature reviews were reference mined for additional studies.11,24,28,29 References in peer-reviewed articles included in the review were also searched and reviewed for additional articles.

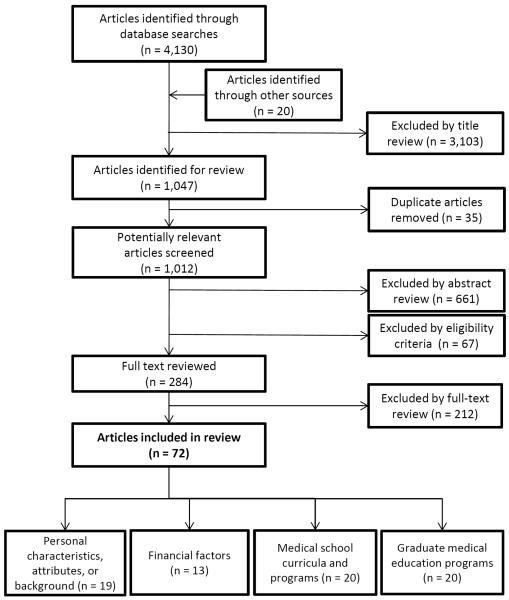

After applying our search criteria and strategy, we removed duplicate articles (Figure 1). Two authors (A.G., S.C.) independently screened 4,130 titles for relevance, with a third author (GM) adjudicating disagreements. After reviewing 1,012 abstracts and applying the eligibility criteria (A.G., S.C., J.U.), we were left with 284 articles for full-text review. We reviewed all articles that met our inclusion criteria and used a form to extract from each of these studies the authors' names, year published, study design, study population, predictors, and outcomes (A.G., E.T., S.C., J.U.). We then constructed evidence tables (S.C., J.U., E.T.) that summarized the studies. We categorized studies into four themes based on our conceptualization of the literature11,24,28,29 and according to the studies' primary focus. Studies that examined multiple predictors were categorized according to both primary and secondary themes. At this stage, we resolved new disagreements through consensus. The analyses also included risk of bias, discussions about descriptions of outcomes, sample, and confounding.30 Articles were archived in Endnote X5 (Thompson Reuters, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection in 2015 systematic review to identify factors associated with primary care physician practice location in underserved urban and rural areas. The included articles were categorized into four themes according to their primary focus.

Results

After applying the criteria to the 284 full-text articles reviewed, we included 72 studies in our review12–20,25–27,31–90 (Table 1). Source data for these studies included the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, state medical licensure boards, Title VII funding records, National Health Service Corps service records, state and national surveys, and medical school and GME program records. All 72 studies were observational, and none were randomized controlled trials.

Table 1.

Studies Examining the Association Between Different Factors/Predictors and Primary Care Physician Practice in an Underserved Urban and Rural Areas, Among 72 Studies Published Through November 2015

| Factors/predictorsa by theme | Practice in underserved or physician shortage areab | |

|---|---|---|

| Studies with negative, mixed, or no association | Studies with positive association | |

| Personal characteristics, attributes, or background c | ||

| Racial-ethnic minority (URM)12–14,16,17,31,36,37,43,55,57,59 | 0 | 12 |

| Second language fluency13,14 | 0 | 2d |

| Growing up in inner-city15,36,51 | 0 | 3 |

| Growing up in rural area39,41,44,45,63,64,71 | 0 | 7 |

| Prior interest in underserved practice36,51,55 | 0 | 3 |

| Prior interest in rural practice44 | 0 | 1 |

| Prior interest in family medicine44,68 | 0 | 2 |

| IMG12,13,32–35,37,38,40,42,51,67 | 4 | 8 |

| Financial factors e | ||

| Educational debt19,20,55 | 2 | 1f |

| NHSC scholarship15,36,46,47,49–51,54 | 0 | 8 |

| Title VII funding exposure18,48,53,54 | 0 | 4 |

| Loan repayment, scholarships and other programs20,52 | 0 | 2 |

| Medical school curricula and programs g | ||

| Primary care specialty12–14,43,51,57,63,71 | 3h | 4 |

| Family medicine specialty12,25,43,51,54,63,65,67 | 1 | 7 |

| Pre-doctoral rural medicine program (2007–2015)25,27,44,62–71,87 | 0 | 14 |

| Medical school of graduation54,55,57 | 0 | 3 |

| Pre-doctoral educational program for underserved56,58,59,61 | 0 | 4 |

| Post-baccalaureate program17,60 | 0 | 2 |

| Graduate medical education programs i | ||

| Family medicine rural track26,72–87,89,90 | 0 | 19 |

| Community health center exposure54,80,83,88 | 0 | 4 |

Abbreviations: IMG indicates international medical graduate; NHSC, National Health Service Corp; refs, references.

Studies that included multiple predictors are included in more than one predictor theme/category. See Method for details regarding categorization according to primary and secondary themes.

In this review, the authors defined “Underserved or physician shortage area” as a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA), Medically Underserved Area (MUA), high limited English proficiency (LEP) area, high poverty/low income area, rural area, safety net (rural health center, community health center, Indian Health Service), and/or area with high percentage of minority populations.

Nineteen studies had a primary focus on personal characteristics, attributes, or background (refs 12–14, 16, 31–45). An additional 11 studies had a secondary focus on factors related to this theme; their primary focus was on financial factors (refs. 15, 51) or medical school curricula and programs (refs 17, 55, 57, 59, 63, 64, 67, 68, 71).

Spanish or Asian languages; outcome defined as high LEP area.

Thirteen studies had a primary focus on financial factors (refs 15, 18–20, 46–54). Two additional studies had a secondary focus on financial factors; their primary focus was on personal characteristics (ref 36) or medical school curricula and programs (ref 55).

One study evaluated the association between debt and participation in the NHSC. Inverse associations were observed.

Of the 20 studies with a primary focus on medical school curricula and programs, 8 focused on underserved practice (refs 17, 55–61) and 12 on rural practice (refs 25, 27, 62–71). An additional eight studies had a secondary focus on factors related to this theme; their primary focus was on personal characteristics (refs 12–14, 43, 44, 51), financial factors (ref 54), or GME programs (ref 87).

One study consisted of osteopathic physicians (ref 57).

The specialties considered “primary care” varied among the studies, but family medicine, general practice, general internal medicine (GIM), and general pediatrics were included in their definitions. In addition, three studies included obstetrics/gynecology, three included geriatrics, four included GIM/pediatrics, and one included adolescent medicine in their definitions of “primary care.” Twenty-six studies clearly defined “underserved” using federal HPSA designation status or MUA parameters.

We identified and categorized studies into four broad themes or clusters that aligned with prior literature28,29: (1) personal characteristics, attributes, or background, such as race/ethnicity, language spoken, and prior interest in practicing in underserved areas; (2) financial factors, such as burden of debt, (3) medical school curricula and programs; and (4) GME programs.

Personal characteristics, attributes, or background

Nineteen studies primarily examined the relationship between physician characteristics and eventual practice location12–14,16,31–45 (Table 1; for study details, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2A at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2].) Eleven additional studies examined selected predictors related to personal characteristics, attributes, or background as a secondary focus.15,17,51,55,57,59,63,64,67,68,71

Twelve studies showed that physicians who self-identified as belonging to an underrepresented minority (URM) group were more likely than their colleagues to locate in high-need practice areas.12–14,16,17,31,36,37,43,55,57,59 In a national study, Rabinowitz et al demonstrated that URM generalists were nearly three times more likely to practice in an underserved area when compared with non-URM physicians.36 State-level studies indicated that black and Latino physicians were more likely to practice in a shortage area when compared with their non-URM colleagues.13,43

Race/ethnicity or URM status also played a role in predicting the type of patient population the physician would serve. Bach et al found that black physicians treating black patients were significantly more likely than white physicians to be practicing in a lower income neighborhood, and that visits by black patients were more likely than visits by white patients to be to black physicians (22.4% vs. 0.7%).16 Komaromy et al found that Hispanic physicians cared for nearly three times as many Hispanic patients as other physicians did, and black physicians cared for almost six times as many black patients compared with other physicians.12

Language was another important predictor of practice location. Two studies showed that Spanish-speaking physicians in California were likely to practice in areas with higher proportions of LEP Spanish-speaking patients.13,14 Physicians fluent in an Asian language were nearly twice as likely to practice in areas with high LEP Asian-language populations when compared with their colleagues.13

Prior interest in underserved practice was also associated with future practice location. Rabinowitz et al found that physicians who held a strong interest in underserved practice prior to medical school were 1.7 times more likely than other physicians to go on to establish a practice in an underserved area.36 Seven studies showed that growing up in a rural hometown or attending a rural high school was associated with practice in a rural area.39,41,44,45,63,64,71

Practice locations of international medical graduates (IMGs) were the focus of 12 studies.12,13,32–35,37,38,40,42,51,67 Polsky et al found that both Asian and Hispanic IMGs were more likely to initially locate in areas in which the patient population matched their own ethnicity.37 A California study indicated that after adjusting for confounding factors, South Asian IMGs were more likely than South Asian U.S. medical graduates [USMGs] to initially practice in rural communities and in designated HPSAs or MUAs.40 Two studies showed that, compared with USMGs, a disproportionate number of IMGs were located in high-need rural counties of more states and in high-poverty areas in large cities.33,34 The distribution of IMGs, however, varied widely between states and areas,32,35,42 and the results were not consistent across these studies.

Financial factors

Thirteen studies primarily examined financial factors underlying physicians' choice of practice location15,18–20,46–54 (Table 1; for study details, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2B at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2). Two additional studies examined selected predictors related to financial factors as a secondary focus.36,55 Two studies did not include a comparison group.47,53 Burden of educational debt was a direct and indirect factor in the choice to practice in an underserved area.19,20,55 In a study of exiting residents in New York, primary care physicians were more likely to locate in an HPSA if their absolute undergraduate medical education debt was less than $100,000.19 The study also suggested that primary care physicians with no debt were three times more likely than primary care physicians with any debt to locate in a shortage area.

Due to the recognized effect of debt burden on practice location choice, multiple authors have examined the effect of scholarship and incentive programs on eventual practice in underserved areas. Title VII of the Public Health Service Act has provided funding support to train and develop primary care clinicians over the past 50 years.53,54 Krist et al's analysis of 9,107 physicians showed that those exposed to Title VII funding during medical school and residency were more likely to locate their practice in underserved areas as compared with those without exposure.18 A second study also found a significant association between Title VII funding and HPSA practice location.48

The National Health Service Corps (NHSC) scholarship provides tuition and living expenses to primary care physician trainees in return for at least two years of service in a medically underserved community. Eight studies found that participation in this program was a significant predictor of practice location.15,36,46,47,49–51,54 Rabinowitz et al found that physicians who had participated in the NHSC were more than twice as likely as those who had not to locate in underserved areas.36 Another study of 2,903 NHSC scholarship recipients found that 20% of physicians assigned to rural areas through the program were still practicing in the county of their original assignment 8–16 years later, and an additional 20% were practicing in a separate rural location.47

Medical school curricula and programs

Twenty studies primarily examined the relationship between medical school curricula and programs and primary care physician practice location17, 25, 27, 55–71 (Table 1). These were further categorized as focusing on underserved urban or rural practice. Eight additional studies examined selected predictors related to medical school curricula and programs as a secondary focus.12–14, 43, 44, 51, 54, 87

Underserved practice

Eight studies primarily examined the impact of medical school curricula and programs encouraging primary care specialty choice and practice location in underserved areas17,55–61 (for study details, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2C at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2].) Two of these studies examined the effects of postbaccalaureate premedical programs on students' eventual choice of practice location.17,60 One study compared graduates of University of California postbaccalaureate programs to a control group of randomly selected physicians from California. This study showed that a greater percentage of the UC postbaccalaureate graduates chose primary care specialties and were working in areas of California with high populations of impoverished and URM patients but not in HPSAs/MUAs.17 A study of the Ohio State University postbaccalaureate program graduates also found higher rates of practice in federally designated underserved areas and in areas with medically uninsured patients.60

Four of these studies studies examined the effects of special medical school programs on increasing students' interest in practicing in underserved areas.56,58,59,61 Over half of the surveyed graduates of the Charles R. Drew Medical Education Program at the University of California, Los Angeles were practicing in medically disadvantaged areas many years post-graduation.59 A 1999 study of Jefferson Medical College's Physician Shortage Area Program (PSAP) showed graduates were more likely than non-graduates to practice in underserved areas.58 Two other studies analyzed graduates of specific medical schools without comparison groups.55,57

Rural practice

We found 12 studies published after 2007 that primarily examined the impact of medical school curricula or special programs on placing graduates in rural practice locations.25,27,62–71 (For study details, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2D at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2].) Two additional studies had a secondary focus on rural practice.44, 87 Rabinowitz et al's 2008 systematic review examining programs aimed at increasing rural practice showed that well over half of program graduates (53–65% weighted average) went on to practice in rural areas.24 Follow-up studies of Jefferson Medical College's PSAP,65,68 as well as studies investigating other programs encouraging rural practice,25,27,62–64,66,70,71 showed the continued success and geographic spread of these programs in cultivating and retaining primary care physicians in rural areas decades after graduation. One study found that participants in rural medicine programs were 10 times more likely to choose rural practice and 4 times more likely to practice any rural primary care specialty compared with IMGs graduating in the same cohort.67 In 5 of the 12 studies, there were no comparisons made to a control group.25,27,62,63,66 In 2 studies, the authors clearly indicated they controlled for potential confounders.64,71

GME programs

Twenty studies focused primarily on GME programs and post-training practice location26,72–90 (Table 1; for study details, see Supplemental Digital Appendix 2E at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2]). Nineteen of these studies focused on family medicine residency programs.26,72–87,89,90 One additional study examined selected predictors related to GME programs as a secondary focus.54 Nine of the 20 studies did not include a comparison or control group.72, 73, 74, 75, 78, 82, 86, 89, 90

Exposure to particular types of residency training sites appeared to have an impact on choice of practice setting. Four studies examined outcomes related to exposure to community health centers during residency training.54,80,83,88 In a study of 3,430 residents who had trained in rural health clinics (RHCs), federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), or critical access hospitals (CAHs) between 2001 and 2005, more than half of CAH trainees were found to be still seeing patients in that setting after graduation.88 In addition, nearly two-fifths of RHC trainees and about one-third of FQHC trainees were still practicing in their respective settings four to eight years post-training.

Discussion

This review synthesizes earlier studies into one of the first comprehensive reviews examining the factors most strongly associated with primary care physician practice in underserved urban and rural areas of the United States. The topic is timely in the face of persistent disparities in the distribution of primary care physicians and the projected need for primary care services nationwide.4 In light of new access to health care insurance coverage via the Affordable Care Act, the placement of primary care physicians in shortage areas and the identification of strategies to effectively recruit them are becoming more pressing.

The results of our review complement studies showing that URM physicians' patient panels are more likely to be composed of minority patients compared with those of other physicians. Research, described elsewhere, that focused on the composition of physician patient panels found that racial/ethnic minority patients were 4 times more likely to receive care from non-white physicians and that patients classified as medically indigent were 2.62 times more likely to receive care from non-white physicians than from white physicians.91,92

A number of the 72 observational studies we reviewed (n = 14; 9 of the 19 studies with a primary focus on personal characteristics, and 5 of the 7 studies with a primary focus on medical school curricula and programs) demonstrated a significant relationship between being an URM physician and practice in an underserved area.12–14,16,17,31,36,37,40,55,57,59,60 Ten of these 14 studies controlled for potential confounders, and their results strongly suggest that a relationship exists between race/ethnicity and eventual choice of practice location. The reasons for this relationship may include having grown up in a high-need environment and identification with the patient population and the health care issues in underserved areas. It follows that increased attention to identification and recruitment of students who originate from underserved areas and who demonstrate an interest in primary care and underserved practice during the medical school admissions process may represent an effective avenue to increasing the physician workforce in high-need areas. Additional research is needed to examine how medical schools are using these personal factors, in isolation or as a composite measure, as part of their admission criteria. It is also unknown how GME programs could use measures that capture these personal factors in the ranking of medical students entering the Match.

Two studies also identified language as an important factor in physician choice of practice location.13,14 Specifically, ethnic identification matching that of the patient population and fluency in a language spoken by the patient population increase the likelihood of a physician locating in an underserved area. Lack of fluency in the predominant language(s) spoken by an underserved population may be a barrier for physicians to practice in these areas with significant LEP populations. Language requirements and offering language learning opportunities during medical school could represent a potential area of intervention to help overcome this barrier and increase physician supply in underserved areas.

Once students with preexisting drive to practice in higher need areas are in medical school, their participation in programs supporting rural and underserved practice goals results in higher rates of actual practice in these locations.59 The aforementioned effects may be further augmented by post-baccalaureate programs.25 These relationships remain true even when measured decades later, suggesting that identifying and supporting interest and motivation early in the medical education process can influence lifelong physician practice patterns. Expanding and replicating medical school curricula and programs that consistently produce clinicians who practice in underserved urban and rural areas should be a high-priority strategic investment for medical education and future research.

Although the association between IMGs and practice location in high-need areas has been demonstrated, the variation in IMG practice patterns among states suggests that there may be other factors influencing this relationship. Research has shown that while IMGs may be initially more likely to practice in HPSAs due to service-obligation opportunities (e.g., the Conrad Program in which they hold temporary visas), many may subspecialize later.93 States vary widely in their policies for service-obligation programs for IMGs.32 It is important to note that IMGs with J-1 visas who get J waivers need to practice in an underserved area for 3–5 years. In return they get residency status and do not need to return home for 2 years after completing postgraduate training.67 It is unclear how this affects where they choose to practice.

The University of California, Los Angeles IMG Program--a physician-training pathway to obtaining U.S. licensure for bilingual English-/Spanish-speaking IMGs who are committed to practicing in underserved areas--has placed IMG physicians in family medicine residency programs throughout California, and it serves as an example of a creative approach to the problem of physician maldistribution.94 IMGs account for one-quarter of all U.S. physicians, and given the magnitude of current and projected physician shortages, any prudent strategy to ameliorate shortages in underserved urban and rural areas would include a role for IMGs.95

Multiple studies also have shown that financial factors play a significant role in determining physician practice setting, independent of preexisting medical trainee characteristics. Arguably, addressing financial factors could have great potential to broadly increase physician practice in high-need areas. While the NHSC scholarship program has had success in this respect, it is likely that the choice to locate in underserved areas may already be endogenous to the group of physicians selected by the program.49 While having no burden of debt may make the choice of locating in HPSAs more likely among primary care physicians, relieving debt burden would not necessarily improve chances of underserved practice among all specialties (e.g., surgery and obstetrics/gynecology).19 Interestingly, the loan repayment programs demonstrate a high physician retention rate in underserved areas compared to other incentivized service-obligation programs.52 More research focusing on new and current financial factors specific to health care and reimbursement reform is needed.

Student intention of underserved and/or rural practice may fluctuate throughout undergraduate medical education, presenting another opportunity for possible intervention. One study conducted by the AAMC using survey data from over 33,000 students found that less than 25% of matriculating students intended to practice in underserved areas; by graduation, this proportion had risen to just 26%.96 An important issue to address may therefore be how to increase interest in underserved practice among students who have not previously considered it.97 As discussed above, in this review we identified 20 studies with a primary focus on GME programs that showed a strong association between the location of physicians' GME site and the location of their eventual practice (Supplemental Digital Appendix 2E at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2]). This relationship has held true in studies published over the past 20 years. In 1995 Seifer at al's study showed that, nationwide, more than half (51%) of physicians remained in the state in which they had completed their graduate medical training.98 Seifer et al also found that the effect was particularly strong among generalist physicians compared to specialists. Twenty years later, Fagan et al's study of practicing family physicians showed that 56% practiced not only in the same state as their GME site, but also within 100 miles of it.22 Thirty-nine percent remained within 25 miles of their GME training location, and 19% stayed within five miles. While Fagan et al did not examine the distribution of other primary care specialties, it is plausible that the physical location of GME training influences a physician's professional network building and familiarity with a patient population.22 Future GME research should focus on other primary care specialties (general internal medicine and pediatrics) in addition to family medicine.

Phillips et al's study further supports the idea that training in settings characterized by outpatient practice and an underserved patient population yields high retention of trainees near their safety net GME sites after graduation.88 A promising intervention to increase underserved physician practice may therefore include bolstering GME training in underserved areas. Although the majority of GME programs in the United States are closely tied to the inpatient setting, developing outpatient training opportunities in underserved areas, either in conjunction with or outside of inpatient training programs, has been shown to encourage long-term, sustainable physician practice in high-need areas.99 Urban underserved tracks could be modeled after successful rural primary care tracks.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include our focus on the multifaceted predictors of practice location in underserved urban and rural areas. There are several limitations to this review. Although we conducted a thorough review of the literature, there is the possibility of publication bias and it is possible that we did not identify all relevant studies. We did not focus on all specialties but instead examined studies focusing on primary care physicians in the United States. The results, therefore, are not generalizable to other specialties or countries. The generalizability of the findings is also limited due to the dynamic nature of current models of primary care practice that focus on team-based care, chronic care models, patient-centered medical homes, and new payment mechanisms. In addition, we could not fully evaluate pooled results for specific outcomes because the studies were observational, and there were no randomized studies,11 likely due to ethical or feasibility issues with randomizing in workforce research. Studies were cross-sectional, uncontrolled case series, and retrospective cohort studies. For this reason, the quality assessment focused on selection bias, detection bias (adjustments for confounders), and reporting bias. When randomization is not possible, future studies should use quasi-experimental designs with control groups and adjust for potential confounders.

Conclusions

In the face of persistent disparities in the distribution of primary care physicians and access to health care in the United States, there is a growing need to identify future physicians who are already interested in underserved or rural practice and to recruit more physicians to high-need areas. From this broad analysis of the factors underlying primary care physicians' choice to practice in underserved areas, promising strategies with demonstrated effectiveness for accomplishing these goals may be identified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: G. Moreno received support from an National Institute on Aging (K23 AG042961-01) Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award, the American Federation for Aging Research, and the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research/Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA grant P30AG021684. The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or the NIH.

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: Reported as not applicable.

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 1] and [LWW INSERT LINK TO SD APP 2].

References

- 1.National Conference of State Legislatures [Accessed March 11, 2016];Health Status of the Uninsured in Geographical Health Professional Shortage Areas: Distribution of Primary Care Physicians. 2011 May; http://www.ncsl.org/

- 2.Health Resources and Services Administration [Accessed March 4, 2016];Primary Medical Care HPSA Designation Criteria. 2014 http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage/hpsas/designationcriteria/primarycarehpsacriteria.html.

- 3.Petterson SM, Phillips RL, Jr., Bazemore AW, Koinis GT. [Accessed March 4, 2016];Unequal distribution of the U.S. primary care workforce. American Family Physician. 2013 87(11) Online. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0601/od1.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges [Accessed March 4, 2016];Physician Supply and Demand Through 2025: Key Findings. 2015 https://www.aamc.org/download/426260/data/physiciansupplyanddemandthrough2025keyfindings.pdf.

- 5.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi L, Macinko J, Starfield B, et al. Primary care, infant mortality, and low birth weight in the states of the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58(5):374–380. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.013078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emery JD, Shaw K, Williams B, et al. The role of primary care in early detection and follow-up of cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2014;11(1):38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: A critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):766–772. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Starfield B, Politzer R, Regan J. Primary care, self-rated health, and reductions in social disparities in health. Health Services Research. 2002;37(3):529–550. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.t01-1-00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrante JM, Lee JH, McCarthy EP, et al. Primary care utilization and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality among Medicare beneficiaries: A population-based, case-control study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;159(7):437–446. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-7-201310010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grobler L, Marais BJ, Mabunda SA, Marindi PN, Reuter H, Volmink J. Interventions for increasing the proportion of health professionals practising in rural and other underserved areas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD005314. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005314.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605163342006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreno G, Walker KO, Morales LS, Grumbach K. Do physicians with self-reported non-English fluency practice in linguistically disadvantaged communities? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):512–517. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1584-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon J, Grumbach K, Bindman AB. Access to Spanish-speaking physicians in California: Supply, insurance, or both. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2004;17(3):165–172. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.3.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu G, Fields SK, Laine C, Veloski JJ, Barzansky B, Martini CJ. The relationship between the race/ethnicity of generalist physicians and their care for underserved populations. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(5):817–822. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lupton K, Vercammen-Grandjean C, Forkin J, Wilson E, Grumbach K. Specialty choice and practice location of physician alumni of University of California premedical postbaccalaureate programs. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):115–120. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823a907f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krist AH, Johnson RE, Callahan D, Woolf SH, Marsland D. VII Funding and physician practice in rural or low-income areas. Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou CF, Lo Sasso AT. Practice location choice by new physicians: The importance of malpractice premiums, damage caps, and health professional shortage area designation. Health Services Research. 2009;44(4):1271–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Spaulding C, Taylor DH. Medical training debt and service commitments: The rural consequences. The Journal of Rural Health. 2000;16(3):264–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine . Report brief. National Academy of Sciences; [Accessd March 4, 2016]. Jul, 2014. Graduate Medical Education that Meets the Nation's Health Needs. https://iom.nationalacademies.org/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2014/GME/GME-RB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fagan EB, Gibbons C, Finnegan SC, et al. Family medicine graduate proximity to their site of training: Policy options for improving the distribution of primary care access. Family Medicine. 2015;47(2):124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, the PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: A systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235–243. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabinowitz HK, Petterson SM, Boulger JG, et al. Comprehensive medical school rural programs produce rural family physicians. American Family Physician. 2011;84(12):1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patterson DG, Longenecker R, Schmitz D, Phillips RL, Skillman SM, Doescher MP. Policy brief: Rural residency training for family medicine physicians: Graduate early-career outcomes, 2008–2012. Rural Training Track Technical Assistance Program; [Accessed March 4, 2016]. Jan, 2013. https://www.raconline.org/rtt/pdf/rural-family-medicine-training-early-career-outcomes-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deutchman M. Medical School Rural Tracks in the US. Policy brief. National Rural Health Association; Washington, DC: [Accessed March 4, 2016]. Sep, 2013. Available at: http://www.ruralhealthweb.org/index.cfm?objectid=28B352C5-3048-651A-FE2D53C27202BAF6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brooks RG, Walsh M, Mardon RE, Lewis M, Clawson A. The roles of nature and nurture in the recruitment and retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(8):790–798. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnighausen T, Bloom DE. Financial incentives for return of service in underserved areas: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:86. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND, Dryden DM, et al. [Accessed March 4, 2016];Assessing the risk of bias of individual studies in systematic reviews of health care interventions. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. 2012 Mar; AHRQ Publication No.12-EHC047-EF. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/

- 31.Cregler LL, McGanney ML, Roman SA, Kagan DV. Refining a method of identifying CUNY Medical School graduates practicing in underserved areas. Academic Medicine. 1997;72(9):794–797. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199709000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baer LD, Ricketts TC, Konrad TR, Mick SS. Do international medical graduates reduce rural physician shortages? Medical Care. 1998;36(11):1534–1544. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mick SS, Lee SY. International and US medical graduates in US cities. Journal of Urban Health : Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1999;76(4):481–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02351505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mick SS, Lee SY. Are there need-based geographical differences between international medical graduates and U.S. medical graduates in rural U.S. counties? The Journal of Rural Health. 1999;15(1):26–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mick SS, Lee SY, Wodchis WP. Variations in geographical distribution of foreign and domestically trained physicians in the United States: “Safety nets” or “surplus exacerbation”? Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50(2):185–202. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski J, Gayle JA. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians' care of underserved populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(8):1225. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polsky D, Kletke PR, Wozniak GD, Escarce JJ. Initial practice locations of international medical graduates. Health Services Research. 2002;37(4):907–928. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.58.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fink KS, Phillips RL, Jr., Fryer GE, Koehn N. International medical graduates and the primary care workforce for rural underserved areas. Health Affairs. 2003;22(2):255–262. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes S, Zweifler J, Schafer S, Smith MA, Athwal S, Blossom HJ. High school census tract information predicts practice in rural and minority communities. The Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21(3):228–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mertz E, Jain R, Breckler J, Chen E, Grumbach K. Foreign versus domestic education of physicians for the United States: A case study of physicians of South Asian ethnicity in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(4):984–993. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wade ME, Brokaw JJ, Zollinger TW, et al. Influence of hometown on family physicians' choice to practice in rural settings. Family Medicine. 2007;39(4):248–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thompson MJ, Hagopian A, Fordyce M, Hart LG. Do international medical graduates (IMGs) “fill the gap” in rural primary care in the United States? A national study. The Journal of Rural Health. 2009;25(2):124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Odom Walker K, Moreno G, Grumbach K. The association among specialty, race, ethnicity, and practice location among California physicians in diverse specialties. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2012;104(1–2):46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30126-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Santana AJ. The relationship between entering medical students' backgrounds and career plans and their rural practice outcomes three decades later. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):493–497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182488c06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duffrin C, Diaz S, Cashion M, Watson R, Cummings D, Jackson N. Factors associated with placement of rural primary care physicians in North Carolina. Southern Medical Journal. 2014;107(11):728–733. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, Ricketts TC., 3rd The National Health Service Corps experience for rural physicians in the late 1980s. JAMA. 1994;272(17):1341–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cullen TJ, Hart LG, Whitcomb ME, Rosenblatt RA. The National Health Service Corps: Rural physician service and retention. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1997;10(4):272–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fryer GE, Jr, Meyers DS, Krol DM, et al. The association of Title VII funding to departments of family medicine with choice of physician specialty and practice location. Family Medicine. 2002;34(6):436–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmes GM. Does the National Health Services Corps improve physician supply in underserved locations? Eastern Economics Journal. 2004;30(4):563–580. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Probst JC, Samuels ME, Shaw TV, Hart GL, Daly C. The National Health Service Corps and Medicaid inpatient care: Experience in a southern state. Southern Medical Journal. 2003;96(8):775–783. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000051140.61690.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brooks RG, Mardon R, Clawson A. The rural physician workforce in Florida: A survey of U.S.- and foreign-born primary care physicians. The Journal of Rural Health. 2003;19(4):484–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pathman DE, Konrad TR, King TS, Taylor DH, Jr, Koch GG. Outcomes of states' scholarship, loan repayment, and related programs for physicians. Medical Care. 2004;42(6):560–568. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000128003.81622.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lipkin M, Zabar SR, Kalet AL, et al. Two decades of Title VII support of a primary care residency: Process and outcomes. Acad Med. 2008;83(11):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31818928ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rittenhouse DR, Fryer GE, Jr, Phillips RL, Jr, et al. Impact of Title VII training programs on community health center staffing and national health service corps participation. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(5):397–405. doi: 10.1370/afm.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson DG, Lloyd SM, Jr., Miller RL. A second survey of graduates of a traditionally black college of medicine. Acad Med. 1989;64(2):87–94. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198902000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campos-Outcalt D, Chang S, Pust R, Johnson L. Commitment to the underserved: Evaluating the effect of an extracurricular medical student program on career choice. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 1997;9(4):276–281. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm0904_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gugelchuk GM, Cody J. Physicians in service to the underserved: An analysis of the practice locations of alumni of Western University of Health Sciences College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, 1982–1995. Academic Medicine. 1999;74(5):557–559. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199905000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Hazelwood CE. A program to increase the number of family physicians in rural and underserved areas. JAMA. 1999;281(3):255–260. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko M, Heslin KC, Edelstein RA, Grumbach K. The role of medical education in reducing health care disparities: The first ten years of the UCLA/Drew Medical Education Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):625–631. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0154-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDougle L, Way DP, Rucker YL. Survey of care for the underserved: A control group study of practicing physicians who were graduates of the Ohio State University College of Medicine Premedical Postbaccalaureate Training Program. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(1):36–40. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46f35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy V, Hurley K, Plumb E, Castellan C, McManus P. Urban underserved program: An analysis of factors affecting practice outcomes. Family Medicine. 2015;47(5):373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glasser M, Hunsaker M, Sweet K, MacDowell M, Meurer M. A comprehensive medical education program response to rural primary care needs. Acad Med. 2008;83(10):952–961. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181850a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Halaas GW, Zink T, Finstad D, Bolin K, Center B. Recruitment and retention of rural physicians: outcomes from the rural physician associate program of Minnesota. The Journal of Rural Health. 2008;24(4):345–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, et al. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: Examining outcomes from the University of Minnesota-Duluth and the Rural Physician Associate Program. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):599–604. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Santana AJ. Increasing the supply of rural family physicians: Recent outcomes from Jefferson Medical College's Physician Shortage Area Program (PSAP) Acad Med. 2011;86(2):264–269. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820469d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Quinn KJ, Kane KY, Stevermer JJ, et al. Influencing residency choice and practice location through a longitudinal rural pipeline program. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1397–1406. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318230653f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rabinowitz HK, Petterson S, Boulger JG, et al. Medical school rural programs: A comparison with international medical graduates in addressing state-level rural family physician and primary care supply. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):488–492. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182488b19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Santana AJ. The relationship between matriculating medical students' planned specialties and eventual rural practice outcomes. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1086–1090. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825cfa54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crump WJ, Fricker RS, Ziegler C, Wiegman DL, Rowland ML. Rural track training based at a small regional campus: Equivalency of training, residency choice, and practice location of graduates. Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1122–1128. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829a3df0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacDowell M, Glasser M, Hunsaker M. A decade of rural physician workforce outcomes for the Rockford Rural Medical Education (RMED) Program, University of Illinois. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1941–1947. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wendling AL, Phillips J, Short W, Fahey C, Mavis B. Thirty years training rural physicians: Outcomes from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine Rural Physician Program [published online ahead of print August 31, 2015] Acad Med. 2016;91:113–119. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Denton DR, Cobb JH, Webb WA. Practice locations of Texas family practice residency graduates, 1979–1987. Acad Med. 1989;64(7):400–405. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baldwin LM, Hart LG, West PA, Norris TE, Gore E, Schneeweiss R. Two decades of experience in the University of Washington Family Medicine Residency Network: Practice differences between graduates in rural and urban locations. The Journal of Rural Health. 1995;11(1):60–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1995.tb00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.West PA, Norris TE, Gore EJ, Baldwin LM, Hart LG. The geographic and temporal patterns of residency-trained family physicians: University of Washington Family Practice Residency Network. The Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1996;9(2):100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frisch L, Kellerman R, Ast T. A cohort study of family practice residency graduates in a predominantly rural state: Initial practice site selection and trajectories of practice movement. The Journal of Rural Health. 2003;19(1):47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tavernier LA, Connor PD, Gates D, Wan JY. Does exposure to medically underserved areas during training influence eventual choice of practice location? Medical Education. 2003;37(4):299–304. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pacheco M, Weiss D, Vaillant K, et al. The impact on rural New Mexico of a family medicine residency. Acad Med. 2005;80(8):739–744. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Edwards JB, Wilson JL, Behringer BA, et al. Practice locations of graduates of family physician residency and nurse practitioner programs: Considerations within the context of institutional culture and curricular innovation through Titles VII and VIII. The Journal of Rural Health. 2006;22(1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Florence JA, Goodrow B, Wachs J, Grover S, Olive KE. Rural health professions education at East Tennessee State University: Survey of graduates from the first decade of the community partnership program. The Journal of Rural Health. 2007;23(1):77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2006.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morris CG, Johnson B, Kim S, Chen F. Training family physicians in community health centers: A health workforce solution. Family Medicine. 2008;40(4):271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Reese VF, McCann JL, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL., Jr. Residency footprints: Assessing the impact of training programs on the local physician workforce and communities. Family Medicine. 2008;40(5):339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Ferguson W, Lasser D. Community dimensions and HPSA practice location: 30 years of family medicine training. Family Medicine. 2009;41(4):255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferguson WJ, Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Lasser DH. Family medicine residency characteristics Associated with practice in a health professions shortage area. Family Medicine. 2009;41(6):405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen F, Fordyce M, Andes S, Hart LG. Which medical schools produce rural physicians? A 15-year update. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):594–598. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d280e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fordyce MA, Doescher MP, Chen FM, Hart LG. Osteopathic physicians and international medical graduates in the rural primary care physician workforce. Family Medicine. 2012;44(6):396–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hixon AL, Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Racsa CP. GIS residency footprinting: Analyzing the impact of family medicine graduate medical education in Hawai'i. Hawai'i Journal of Medicine & Public Health. 2012;71(4 Suppl 1):31–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petrany SM, Gress T. Comparison of academic and practice outcomes of rural and traditional track graduates of a family medicine residency program. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):819–823. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318290014c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Phillips RL, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Do residents who train in safety net settings return for practice? Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1934–1940. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ross R. Fifteen-year outcomes of a rural residency: Aligning policy with national needs. Family Medicine. 2013;45(2):122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crane S, Jones G. Innovation in rural family medicine training: The Mountain Area Health Education Center's rural-track residency program. North Carolina Medical Journal. 2014;75(1):29–30. doi: 10.18043/ncm.75.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273(19):1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians' role in the care of underserved patients: Diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(2):289–291. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ogunyemi D, Edelstein R. Career intentions of U.S. medical graduates and international medical graduates. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1132–1137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dowling PT, Bholat MA. Utilizing international medical graduates in health care delivery: Brain drain, brain gain, or brain waste? A win-win approach at University of California, Los Angeles. Primary Care. 2012;39(4):643–648. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.American Medical Association [Accessed March 4, 2016];IMGs in the United States. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/member-groups-sections/international-medical-graduates/imgs-in-united-states.page.

- 96.Grbic D, Slapar F. [Accessed March 4, 2016];Changes in medical students' intentions to serve the underserved: matriculation to graduation. Association of American Medical Colleges. Analysis in Brief. 2010 9(8) https://www.aamc.org/download/137518/data/aib_vol9_no8.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Erikson CE, Danish S, Jones KC, Sandberg SF, Carle AC. The role of medical school culture in primary care career choice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1919–1926. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seifer SD, Vranizan K, Grumbach K. Graduate medical education and physician practice location. Implications for physician workforce policy. JAMA. 1995;274(9):685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Xierali IM, Sweeney SA, Phillips RL, Jr., Bazemore AW, Petterson SM. Increasing graduate medical education (GME) in critical access hospitals (CAH) could enhance physician recruitment and retention in rural America. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2012;25(1):7–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.01.110188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.