Abstract

Introduction

The autonomic nervous system plays an integral role in the maintenance of homeostasis during times of stress. The functioning of the autonomic nervous system in patients with functional movement disorders (FMD) is of particular interest given the hypothesis that converted psychological stress plays a critical role in FMD disease pathogenesis. We sought to investigate autonomic nervous system activity in FMD patients by examining heart rate variability (HRV), a quantitative marker of autonomic function.

Methods

35 clinically definite FMD patients and 38 age- and sex-matched healthy controls were hospitalized overnight for continuous electrocardiogram recording. Standard time and frequency domain measures of HRV were calculated in the awake and asleep stages. All participants underwent a thorough neuropsychological battery, including the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression scales and the Beck Depression Inventory.

Results

Compared to controls, patients with FMD exhibited decreased root mean square of successive differences between adjacent NN intervals (RMSSD) (p = 0.02), a marker of parasympathetic activity, as well as increased mean heart rate (p = 0.03). These measures did not correlate with the depression and anxiety scores included in our assessment as potential covariates.

Conclusion

In this exploratory study, patients with FMD showed evidence of impaired resting state vagal tone, as demonstrated by reduced RMSSD. This decreased vagal tone may reflect increased stress vulnerability in patients with FMD.

Keywords: Functional movement disorders, psychogenic movement disorders, conversion disorder, stress, autonomic nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Accounting for up to 20% of patients evaluated at specialized movement disorders neurology clinics, patients with functional movement disorders (FMD) are often among the most disabled[1] and the most refractory to treatment. The underlying pathogenesis of the disorder remains poorly understood. Many neurologists consider elevated stress levels to be a universal feature of patients with FMD[2], and increased stress is hypothesized to contribute to disease pathogenesis. Evaluating autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity in patients with FMD is therefore of particular interest given the role of the ANS in the maintenance of homeostasis during times of stress.

Heart rate variability (HRV), reflecting the oscillation in the inter-beat interval (normal-to-normal (NN) interval), provides a quantitative assessment of autonomic function. In addition to acting as a predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality[3], HRV is also considered to serve as a marker of psychological well-being[4, 5]. Among healthy adults, resting-state HRV has been demonstrated to correlate with socially adaptive coping strategies[6]. Vagal tone in particular has been proposed to serve as a physiological marker of stress vulnerability[7], with impaired vagal tone reflecting impaired ability to react to external stressors. Decreased HRV has been demonstrated in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, including psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES)[8-10], major depressive disorder[11], and generalized anxiety disorder[12]. To date, HRV has not been examined in patients with FMD.

In this exploratory study, we investigated whether FMD patients exhibit impairments in ANS function by comparing standard measures of HRV derived from continuous ECG recordings collected during awake and asleep epochs in FMD patients and their age- and sex-matched healthy controls (HCs).

METHODS

Participants

Thirty-five patients with a diagnosis of “clinically definite” FMD[13] were recruited from the Human Motor Control clinic at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) between October 2011 and March 2015. Thirty-eight age- and sex-matched HCs were recruited from the NIH Clinical Research Volunteer Program database. Participants partially overlap with those reported in a previous manuscript exploring the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in FMD[14]. Exclusion criteria for all participants included: a) history of cardiac disease; b) use of heart-rate altering medication; c) comorbid neurological disease; d) comorbid psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, current substance abuse or current depressive episode; e) history of traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness; f) active autoimmune disorder; g) current suicidal ideation; h) disease severity requiring inpatient treatment; and i) use of tricyclic antidepressants or antiepileptic medication. HCs were additionally excluded for use of any antidepressant medication within the last six months. The NIH institutional review board approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent.

Heart rate collection and analysis

Participants were hospitalized overnight for continuous Holter monitoring ranging from 14 to 24 hours total duration. Holter data were analyzed using Impresario software. All recordings were visually inspected and manually edited to identify and remove artifacts and non-beats. Data were subsequently split into awake and asleep epochs and imported into Matlab for calculation of standard HRV time and frequency domain measures recommended by the task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology[15]. Five time domain measures of HRV were calculated: RMSSD (root mean square of successive differences between adjacent NN intervals); SDNN (standard deviation of NN intervals); SDANN (standard deviation of the averages of NN intervals calculated over all 5 minute segments); NN50 (the number of pairs of adjacent NN intervals differing by more than 50 milliseconds); and pNN50 (the NN50 count divided by the total number of NN intervals). RMSSD reflects the beat-to-beat variation in heart rate, and is the primary time domain measure used to assess parasympathetic sources of HRV. NN50 and pNN50 also estimate high frequency variation, and are highly correlated with RMSSD, although RMSSD is thought to possess superior statistical properties. SDNN and SDANN are used as estimates of overall HRV, and do not distinguish between sympathetic or parasympathetic sources of variability[15]. Frequency domain measures included: total power (TP); power in high frequency (HF) (0.15 – 0.4 Hz), low frequency (LF) (0.04 – 0.15 Hz), and very low frequency (VLF) (<0.04 Hz) ranges; LF and HF in normalized units (LFn and HFn); and the ratio of LF to HF (LF/HF). HF power is predominantly mediated by the parasympathetic nervous system, whereas LF power reflects both sympathetic and parasympathetic activity[15]. Mean heart rate (HR) was also assessed.

Neuropsychological assessment

All participants met with a clinical psychologist (R.A.), who administered the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)[16] and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)[17]. Participants also completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)[18].

Statistical Analysis

Box-Cox transformation was applied to HRV measures to achieve approximately normal distributions. To investigate possible group effects on HRV measures, repeated measures analysis of covariance (rm-ANCOVA) was performed with time (awake/asleep epochs) as within-subject variable, group (FMD, HC) as between-subject variable, and age and sex as covariates. To determine whether to include scales of depression and anxiety in our statistical model as covariates, we evaluated the association between HRV parameters and well-validated scales of anxiety and depression (HAM-A and HAM-D, respectively) using rm-ANCOVA. Given the absence of significant association between HAM-A score and any of the HRV parameters on rm-ANCOVA, this scale was not included as a covariate in our final model. A significant interaction between group and HAM-D score was detected, thus rm-ANCOVA evaluating the association between HRV and HAM-D score was performed separately for the two groups (FMD, HC). In the FMD group, we did not detect a significant association between HAM-D score and any of the HRV parameters. The HAM-D score among all participants in the HC group was in the normal range (Table 1), and therefore any potential association between HAM-D score and HRV parameter was not deemed meaningful. Given these findings, HAM-D was not included as a covariate in our final model.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and neuropsychiatric features

| FMD patients (n=35) |

Healthy Controls (n=38) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 44.0 ± 10.7 (26-62) |

41.0 ± 9.7 (24-61) |

0.21 |

|

| |||

| Sex, F/M | 26/9 | 28/10 | 0.95 |

|

| |||

|

Number taking CNS-

acting medicationa |

18 | 0 | - |

|

| |||

| Disease duration, y | 5.6 ± 5.3 (0.4-19) |

- | - |

|

| |||

| HAM-A | 12.5 ± 8.1 (0-34) |

3.0 ± 2.5 (0-8) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||

| HAM-D | 9.3 ± 6.4 (0-26) |

3.0 ± 2.5 (0-5) |

<0.001 |

|

| |||

| BDI | 7.2 ± 6.3 (0-29) |

3.0 ± 4.4 (0-19) |

0.002 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (range) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: FMD = functional movement disorders; CNS = central nervous system; HAM-A = Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory.

CNS-acting medications included sertraline (n=3), citalopram (n=1), escitalopram (n=1), duloxetine (n=1), desvenlafaxine (n=1), clonazepam (n=8), lorazepam (n=1), diazepam (n=1), alprazolam (n=1), trihexyphenidyl (n=2), gabapentin (n=4), baclofen (n=1), adderall (n=1), acetazolamide (n=1), carbidopa/levodopa (n=1), ropinirole (n=1).

To explore a possible relationship between disease duration and HRV, linear correlations between disease duration and measures of HRV were assessed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

Group differences in HRV might be confounded by group differences in the use of CNS-acting medications, specifically the use of SSRI and SNRI anti-depressants[19]. To address this potential confounder, we performed additional rm-ANCOVA analysis excluding the seven patients who were taking SSRIs or SNRIs. We also compared the means of the relevant HRV parameters in medicated versus non-medicated patients using two-sample student’s t-tests. Significance threshold was set at p < 0.05. Given the exploratory nature of the study, correction for multiple comparisons was not performed.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

35 FMD patients and 38 age- and sex-matched HCs were included in the analysis. Groups did not differ significantly in terms of demographic data (Table 1). Patients scored significantly higher than HCs on anxiety and depression rating scales (Table 1). Clinically, patients reported an average disease duration of 5.6 years (SD 5.3). Patients self-reported a range of involuntary movements, including tremor (71%), other jerking movements (63%), abnormal gait and/or balance (63%), abnormal speech (43%), abnormal posturing/dystonia (40%), and paresis (31%).

HRV Analysis

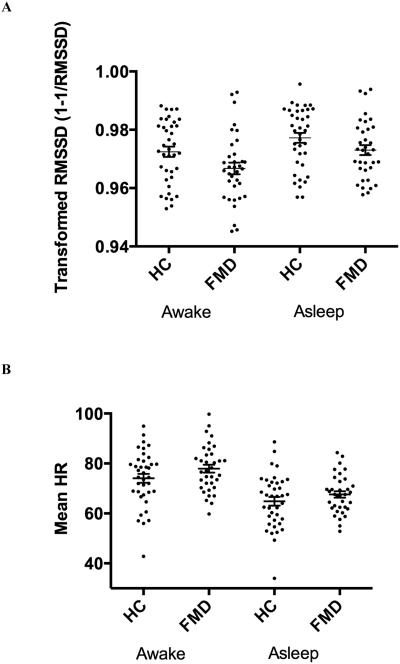

To investigate possible group effects on HRV, we performed rm-ANCOVA with group (patients, HCs) as the between-subject factor and time (awake/asleep epochs) as the within-subject factor. A moderate effect of group was seen for RMSSD (F(1,141) = 5.22, p = 0.02) and mean HR (F(1,141) = 4.73, p = 0.03) (Table 1; Figure 1). There were no significant differences between patients and HCs for the remaining time and frequency domain measures of HRV, although several measures, including NN50, pNN50, HF, HFn, and the LF/HF ratio, trended to significance (Table 2; p < 0.10). As expected, a significant effect of time was observed for ten of the 13 HRV measures (data not shown). There were no significant group x time interactions (data not shown). Disease duration, while found to correlate with mean HR (awake and asleep epochs: r=0.39, p=0.02), did not correlate with any of the measures of HRV (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots comparing (A) RMSSD and (B) mean heart rate in FMD patients and HCs in the awake and asleep epochs. Error bars: mean ± SEM.

Abbreviations: RMSSD - root mean square of successive differences between adjacent NN intervals, FMD – functional movement disorders, HC – healthy control, SEM – standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

Time and frequency domain measures of HRV in FMD patients and controls

| FMD | HC | F-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSSD | 33.9*

(31.3-36.9) |

38.9 (35.7-42.7) |

5.22 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| NN50 | 161 (129-201) |

213 (172-264) |

3.32 | 0.07 |

|

| ||||

| pNN50 | 3.98 (3.12-5.07) |

5.51 (4.37-6.96) |

3.71 | 0.06 |

|

| ||||

| SDNN | 78.1 (72.4-84.1) |

82.6 (76.9-88.7) |

1.25 | 0.26 |

|

| ||||

| SDANN | 44.1 (40.6-47.9) |

47.1 (43.7-50.8) |

1.2 | 0.28 |

|

| ||||

| TP | 3040 (2600-3560) |

3370 (2900-3910) |

0.96 | 0.33 |

|

| ||||

| HF | 279 (233-339) |

352 (292-428) |

2.95 | 0.09 |

|

| ||||

| HFn | 0.26 (0.24-0.28) |

0.29 (0.27-0.31) |

3.65 | 0.06 |

|

| ||||

| LF | 873 (736-1040) |

929 (789-1090) |

0.31 | 0.58 |

|

| ||||

| LFn | 0.73 (0.71-0.75) |

0.70 (0.68-0.72) |

2.76 | 0.10 |

|

| ||||

| LF/HF | 2.94 (2.62-3.29) |

2.57 (2.30-2.86) |

2.9 | 0.09 |

|

| ||||

| VLF | 1750 (1510-2020) |

1970 (1710-2270) |

1.45 | 0.23 |

|

| ||||

|

Mean

HR |

72.8*

(70.5-75.1) |

69.4 (67.2-71.7) |

4.73 | 0.03 |

Data are presented as back-transformed means (95% confidence interval); data represent combined awake and asleep epochs.

Abbreviations: HR = heart rate; FMD = functional movement disorders; HC = healthy control; RMSSD = root mean square of successive differences between adjacent NN intervals; NN50 = number of pairs of adjacent NN intervals differing by more than 50 milliseconds; pNN50 = NN50 count divided by total number of NN intervals; SDNN = SD of NN intervals; SDANN = SD of averages of NN intervals calculated over all 5 minute segments; TP = variance of all NN intervals; HF = power in high frequency range (0.15-0.4Hz); HFn = HF power in normalized units; LF = power in low frequency range (0.04-0.15Hz); LFn = LF power in normalized units; VLF = power in very low frequency range (0.003-0.04Hz).

p<0.05 for comparison between patients and HCs.

Although the effect of antidepressants on HRV is debated[5], some studies suggest that antidepressant use, including the use of selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors as well as serotonergic and noradrenergic reuptake inhibitors, results in reduced HRV[19]. To confirm that the observed group differences in HRV were not secondary to group differences in use of serotonergic reuptake inhibitors, we repeated our statistical analysis after excluding individuals taking SSRIs or SNRIs. While a significant effect of group continued to be seen for mean HR (F(1,127) = 7.37, p = 0.01), there was no longer a significant effect of group for RMSSD (F(1,127) = 3.1, p = 0.08) when the seven patients on SSRIs or SNRIs were excluded from the analysis. This loss of significance could represent a medication effect or the loss of power due to a smaller sample size. We confirmed that RMSSD did not differ between medicated and non-medicated patients (awake epoch: p = 0.64; asleep epoch: p = 0.35), suggesting that in our cohort the loss of significance is secondary to loss of power rather than to a true effect of medication on RMSSD.

DISCUSSION

Our study represents the first investigation in the literature to date assessing ANS function in patients with FMD. We provide evidence for impaired activity of the parasympathetic nervous system in FMD patients, as determined by reduced RMSSD. RMSSD has been recommended as the preferred means of assessing short-term components of HRV, and reflects the integrity of vagal tone[15]. Several additional markers of parasympathetic activity, notably the time domain measures NN50 and pNN50 and the frequency domain measure HF, also trend to statistical significance, consistent with reduced vagal tone in our FMD cohort. HRV measures that reflect a combination of parasympathetic and sympathetic activity were not found to differ between groups.

Although there is a substantial body of literature demonstrating impaired ANS function in anxiety[12] and mood disorders[11], little is known about autonomic function in conversion disorder. Consistent with our findings in the FMD population, several studies have demonstrated impairments in HRV in patients with PNES, both during interictal[8] and peri-ictal periods[9, 20].

Vagally mediated HRV has been implicated in a number of conditions, including metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease[21]. The vagus nerve plays an important role in immune function, and impaired vagally mediated HRV has been demonstrated to predict elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines[22]. In addition, vagal tone has been proposed as a physiological marker of stress vulnerability, with decreased resting vagal tone reflecting impaired ability of the individual to adapt appropriately to environmental demands[7]. Indeed, prior studies are consistent with an increased vulnerability to psychological stressors in FMD patients, with patients demonstrating a greater startle response to arousing stimuli[23] and an inability of the amygdala to habituate to emotionally salient stimuli[24].

Our study contrasts with previous work from our group demonstrating normal functioning in FMD patients of another critical stress response system, the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis[14]. However, while the HPA axis and ANS generally act in a complementary manner to maintain homeostasis during times of stress, various upstream modulators, for example within the limbic forebrain, are known to preferentially influence the ANS[25]. Additionally, exposure to chronic past stress may differentially impact the HPA axis and the ANS. Chronic stress is known to alter the structure and function of brain regions involved in regulating both the HPA axis and the ANS. In an animal model of chronic stress, rodents exposed to chronic mild stress exhibited reduced HRV and elevated HR[26]. HRV, and specifically vagally mediated HRV, may represent a more sensitive means of assessing chronic prior stress in our FMD patient group, despite their normal cortisol response.

A noteworthy strength of our study includes the extensive psychometric information available to assess for potential confounders. We sought to control for group differences in psychiatric co-morbidities, and failed to find association between HRV and several well-validated clinical scales of anxiety and depression in our patient population. While prior studies have demonstrated moderate effects of major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder on HRV[11, 12], our population was likely not sufficiently powered to adequately demonstrate this effect, with 23% (8/35) patients demonstrating clinically significant anxiety and 23% (8/35) demonstrating clinically significant depression based on scores on HAM-A and HAM-D, respectively. Additional strengths of our study include the relatively long duration for ECG recording, and standardized setting in which the recording was obtained.

Several limitations should be considered. First, approximately half of the FMD patients included in our study were taking CNS-acting medications. We did not, however, detect a difference in RMSSD between medicated and non-medicated patients, suggesting that the reduced RMSSD seen in our FMD patient cohort was not due to medication effect. In addition, our study was exploratory in nature, and results must be interpreted with caution given that correction for multiple comparisons was not performed. Nevertheless, nearly half of the HRV measures exhibited either statistically significant differences between FMD patients and HCs or trended to significance (p < 0.10).

Although all patients were symptomatic at time of admission to our study, we did not differentiate between patients with paroxysmal versus more continuous functional movements in our analysis. Reduced HRV is detected peri-ictally[9] as well as interictally in patients with PNES[8]; we similarly suspect that autonomic impairment in FMD patients would be present both during the presence and absence of functional movements, although this remains to be demonstrated.

Furthermore, although RMSSD is significantly different between groups, the range of values overlaps considerably between groups, as illustrated in Figure 1. Therefore, while as a population FMD patients exhibit impaired vagal tone as determined by reduced RMSSD, this measure alone cannot be considered as a biomarker for distinguishing patients from healthy controls.

Finally, while we have demonstrated that on average patients with FMD exhibit impaired vagal tone, the link between FMD and autonomic dysfunction may not be a directly causative one. It is possible, for example, that patients with FMD exhibit poor coping strategies that might predispose them to both impaired autonomic function[6] as well as FMD. Additional studies are necessary to further address this issue.

Conclusions

Our study examines ANS function in FMD patients, and demonstrates that these patients exhibit decreased vagally mediated HRV. Decreased parasympathetic tone may result in inadequate protection from sympathetic stressors in these patients. The underlying cause of this autonomic imbalance in FMD patients merits further study.

We examine heart rate variability in functional movement disorders (FMD) patients

Time and frequency HRV measures were assessed in FMD patients and healthy controls

FMD patients exhibit reduced resting vagal tone compared to healthy controls

Decreased vagal tone may reflect increased stress vulnerability in FMD patients

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the NINDS Intramural Program. We would like to thank Dr. Robert Brychta (NIDDK/NIH) and Peter Lauro (NINDS/NIH) for assistance with the Matlab program used for HRV analysis. We would like to acknowledge Elaine Considine, R.N., for her assistance with study coordination.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: Dr. Hallett is involved in the development of Neuroglyphics for tremor assessment, and has a collaboration with Portland State University to develop sensors to measure tremor. He serves as Chair of the Medical Advisory Board for and may receive honoraria and funding for travel from the Neurotoxin Institute. He may accrue revenue on US Patent #6,780,413 B2 (Issued: August 24, 2004): Immunotoxin (MAB-Ricin) for the treatment of focal movement disorders, and US Patent #7,407,478 (Issued: August 5, 2008): Coil for Magnetic Stimulation and methods for using the same (H-coil); in relation to the latter, he has received license fee payments from the NIH (from Brainsway) for licensing of this patent. Dr. Hallett's research at the NIH is largely supported by the NIH Intramural Program. Supplemental research funds have been granted by BCN Peptides, S.A. for treatment studies of blepharospasm, Medtronics, Inc., for studies of deep brain stimulation, Parkinson Alliance for studies of eye movements in Parkinson’s disease, UniQure for a clinical trial of AAV2-GDNF for Parkinson Disease, Merz for treatment studies of focal hand dystonia, and Allergan for studies of methods to inject botulinum toxins.

Dr. Epstein serves as President of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, and is on the Editorial Board for Psychosomatics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHORS’ ROLES

Dr. Maurer was involved in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and writing the first draft and final version of the paper. Dr. Liu was involved in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript revision. Dr. LaFaver was involved in study conception, data analysis and acquisition, and manuscript revision. Dr. Ameli and Mr. Toledo were involved in data acquisition and manuscript revision. Dr. Wu was involved in data analysis and manuscript revision. Dr. Epstein was involved in study conception, data acquisition and manuscript revision. Dr. Hallett was involved in study conception, data interpretation, and manuscript revision.

All authors have approved the article.

The remaining authors have no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- [1].Anderson KE, Gruber-Baldini AL, Vaughan CG, Reich SG, Fishman PS, Weiner WJ, et al. Impact of psychogenic movement disorders versus Parkinson's on disability, quality of life, and psychopathology. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2007;22:2204–9. doi: 10.1002/mds.21687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kanaan R, Armstrong D, Barnes P, Wessely S. In the psychiatrist's chair: how neurologists understand conversion disorder. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2009;132:2889–96. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kleiger RE, Stein PK, Bigger JT., Jr. Heart rate variability: measurement and clinical utility. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2005;10:88–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.10101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thayer JF, Brosschot JF. Psychosomatics and psychopathology: looking up and down from the brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1050–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kemp AH, Quintana DS. The relationship between mental and physical health: insights from the study of heart rate variability. International journal of psychophysiology : official journal of the International Organization of Psychophysiology. 2013;89:288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Geisler FC, Kubiak T, Siewert K, Weber H. Cardiac vagal tone is associated with social engagement and self-regulation. Biological psychology. 2013;93:279–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Porges SW. Vagal tone: a physiologic marker of stress vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1992;90:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ponnusamy A, Marques JL, Reuber M. Heart rate variability measures as biomarkers in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: potential and limitations. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2011;22:685–91. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ponnusamy A, Marques JL, Reuber M. Comparison of heart rate variability parameters during complex partial seizures and psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1314–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bakvis P, Roelofs K, Kuyk J, Edelbroek PM, Swinkels WA, Spinhoven P. Trauma, stress, and preconscious threat processing in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1001–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kemp AH, Quintana DS, Felmingham KL, Matthews S, Jelinek HF. Depression, comorbid anxiety disorders, and heart rate variability in physically healthy, unmedicated patients: implications for cardiovascular risk. PloS one. 2012;7:e30777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chalmers JA, Quintana DS, Abbott MJ, Kemp AH. Anxiety Disorders are Associated with Reduced Heart Rate Variability: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2014;5:80. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Williams DT, Ford B, Fahn S. Phenomenology and psychopathology related to psychogenic movement disorders. Advances in neurology. 1995;65:231–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Maurer CW, LaFaver K, Ameli R, Toledo R, Hallett M. A biological measure of stress levels in patients with functional movement disorders. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2015;21:1072–5. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. The British journal of medical psychology. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of general psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Licht CM, de Geus EJ, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Longitudinal evidence for unfavorable effects of antidepressants on heart rate variability. Biological psychiatry. 2010;68:861–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].van der Kruijs SJ, Vonck KE, Langereis GR, Feijs LM, Bodde NM, Lazeron RH, et al. Autonomic nervous system functioning associated with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Analysis of heart rate variability. Epilepsy & behavior : E&B. 2015;54:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF. The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. International journal of cardiology. 2010;141:122–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.09.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jarczok MN, Koenig J, Mauss D, Fischer JE, Thayer JF. Lower heart rate variability predicts increased level of C-reactive protein 4 years later in healthy, nonsmoking adults. Journal of internal medicine. 2014;276:667–71. doi: 10.1111/joim.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Seignourel PJ, Miller K, Kellison I, Rodriguez R, Fernandez HH, Bauer RM, et al. Abnormal affective startle modulation in individuals with psychogenic [corrected] movement disorder. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2007;22:1265–71. doi: 10.1002/mds.21451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, Ameli R, Roelofs K, LaFrance WC, Jr., et al. Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2010;133:1526–36. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK. Evaluation of baroreceptor reflex function in the chronic mild stress rodent model of depression. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70:435–43. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816ff7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Thayer JF, Lane RD. The role of vagal function in the risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Biological psychology. 2007;74:224–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]