Abstract

Purple foliage always appears in Camellia sinensis families; however, the transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis is unknown. The tea bud sport cultivar ‘Zijuan’ confers an abnormal pattern of anthocyanin accumulation, resulting in a mutant phenotype that has a striking purple color in young foliage and in the stem. In this study, we aimed to unravel the underlying molecular mechanism of anthocyanin biosynthetic regulation in C. sinensis. Our results revealed that activation of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor (TF) anthocyanin1 (CsAN1) specifically upregulated the bHLH TF CsGL3 and anthocyanin late biosynthetic genes (LBGs) to confer ectopic accumulation of pigment in purple tea. We found CsAN1 interacts with bHLH TFs (CsGL3 and CsEGL3) and recruits a WD-repeat protein CsTTG1 to form the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) complex that regulates anthocyanin accumulation. We determined that the hypomethylation of a CpG island in the CsAN1 promoter is associated with the purple phenotype. Furthermore, we demonstrated that low temperature and long illumination induced CsAN1 promoter demethylation, resulting in upregulated expression to promote anthocyanin accumulation in the foliage. The successful isolation of CsAN1 provides important information on the regulatory control of anthocyanin biosynthesis in C. sinensis and offers a genetic resource for the development of new varieties with enhanced anthocyanin content.

Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) is an important global commercial crop, and is primarily consumed as a non-alcoholic beverage made from the processed leaves. The tea beverage yields many health benefits to humans due to the extensive secondary metabolites found in tea leaves, including flavonoids, theanine, and volatile oils1. Flavonoids, including catechins, anthocyanins, proanthocyanins, flavonols and phenolic acids, are a large group of phenolic secondary metabolites and have potential beneficial properties for human health2.

Anthocyanins are the largest group of water-soluble pigments in the plant kingdom and belong to the family of compounds known as flavonoids. Anthocyanins display a wide range of biological functions, such as attracting pollinators and seed dispersers and protecting plants against various biotic and abiotic stresses2,3. To date, most anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway genes and numerous regulatory factors have been identified from studies in Arabidopsis, maize, petunia, apple, and other plant species4,5,6,7. Transcriptional regulation of structural genes appears to be a major mechanism by which anthocyanin biosynthesis is regulated in plants2. In many species studied to date, regulation occurs through a complex of MYB transcription factors (TFs), basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TFs, and WD-repeat proteins in the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complex2,8. The MYB member of this complex often appears to be the major determinant of variation in anthocyanin pigmentation6. Activation of anthocyanin master regulators, including AtMYB75 in Arabidopsis, SlANT1 in tomato, MdMYB10 and MdMYB110a in apple, BoMYB2 in cauliflower, McMYB10 in crabapple, and RsMYB1 in radish, is associated with upregulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic structural genes and results in anthocyanin accumulation5,7,9,10,11,12,13. In contrast, loss of function or repression of VvMYBA1 in grapevine, MdMYB10 in apple, EgVIR in oil palm, and PcMYB10 in pear leads to color loss in normal anthocyanin-accumulating tissues14,15,16,17.

Although many studies have investigated the mechanisms underlying the control of anthocyanin production in flowers, fruits, and model plants, few studies have focused on tea plants. Because C. sinensis is difficult to culture in vitro, difficult to transform, and has a large genome1, the underlying molecular mechanisms of transcriptional control of anthocyanin accumulation in the tea plant remain unknown. Mutant analyses have facilitated gene discovery and elucidation of the regulatory control of anthocyanin biosynthesis7,18. The purple foliage cultivar ‘Zijuan’ is a somatic mutant selected from the Yunnan Daye cultivar (Camellia sinensis var. assamica (Mast.) Kitamura), in which the anthocyanin content was reported to be approximately three times that found in other Chinese purple tea cultivars19. Thus, this mutant provides an excellent opportunity to uncover the regulatory control of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tea plants. To obtain more insight into the high levels of anthocyanin accumulation in ‘Zijuan’, a comparative transcriptome strategy was used, with the aim of revealing the underlying molecular mechanisms. We found that the CsAN1 homologue of AtMYB113 in Arabidopsis and anthocyanin LBG expression levels were highly correlated with anthocyanin accumulation. Two candidate bHLH partners and a WD-repeat protein were also isolated. Further analysis revealed that the methylation and demethylation of the CsAN1 promoter may be the factor causing purple foliage, thus providing a mechanism by which anthocyanin transcriptional regulation can be modulated differently in plants.

Results

Analysis of anthocyanin content in different C. sinensis cultivars

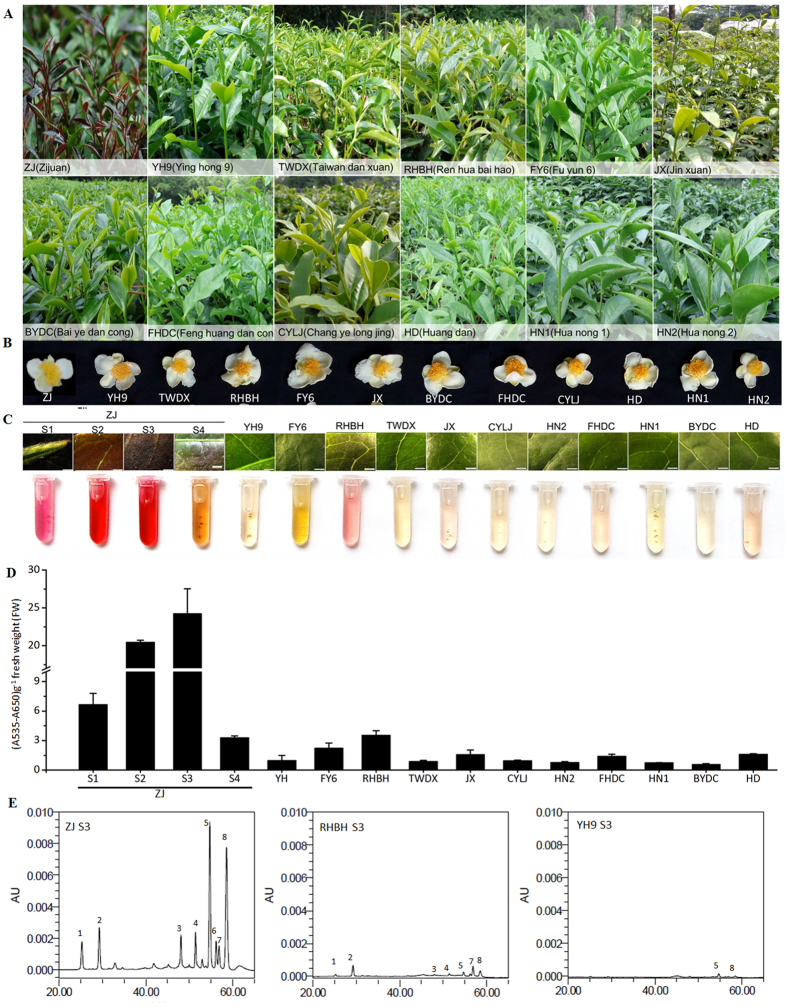

The purple foliage tea plants grew and developed normally when compared to green foliage under normal growth conditions in a tea garden. ‘Zijuan’ (‘ZJ’) exhibited a tissue-specific pattern of anthocyanin accumulation. Intense purple coloration was mainly observed in young leaves and stems (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the purple color was almost absent in mature leaves, stems and flower petals (Fig. 1A–C). Consistent with the observed phenotypes, ‘ZJ’ showed an abundant level of anthocyanin accumulation in stage S1 leaves and the highest accumulation in stage S3 leaves, while the stage S4 leaves accumulated little anthocyanin. In contrast, only trace amounts of anthocyanin were detected in stage S3 leaves of green-colored cultivars (Fig. 1D). To examine the composition of anthocyanin accumulated in ‘ZJ’ leaves, we performed HPLC analysis of anthocyanin compound composition. The results suggested that ‘ZJ’ contains two major anthocyanin peaks at 520 nm; cyanidin-3-O-galactoside (peak 5) and delphinidin-3-O-galactoside (peak 8) were the main coloration anthocyanin components in the ‘ZJ’ leaves (Fig. 1E), which is consistent with previous results in tea plants20,21. In contrast, anthocyanin peaks were almost undetectable in the ‘RHBH’ and ‘YH9’ cultivars. In general, anthocyanin accumulation in the purple-red foliage of ‘ZJ’ is higher than in other cultivars, indicating that anthocyanin accumulation is responsible for the purple coloration in tea.

Figure 1. Analysis of anthocyanin content in different C. sinensis cultivars.

Phenotypes of C. sinensis leaves (A) and flowers (B). (C) Close-up of purple foliage cultivar ‘Zijuan’ (‘ZJ’) leaf in stages S1, S2, S3 and S4 and green foliage cultivars leaves in stage S3 and corresponding extraction of anthocyanin. Bar = 1 mm. S1, bud; S2, 7 days after budding (DAB); S3, 15 DAB; S4, 40 DAB. (D) Analysis for anthocyanin as shown in (C). Error bars on each symbol indicate the mean ± SD of three biological repeats. (E) HPLC traces at 520 nm of red and evergreen foliage cultivars ‘ZJ’, ‘RHBH’ and ‘YH9’ in stage S3 leaves. 5, cyanidin-3-O-galactoside, 8, delphinidin-3-O-galactoside.

Anthocyanin LBGs and CsAN1 are upregulated in red foliage

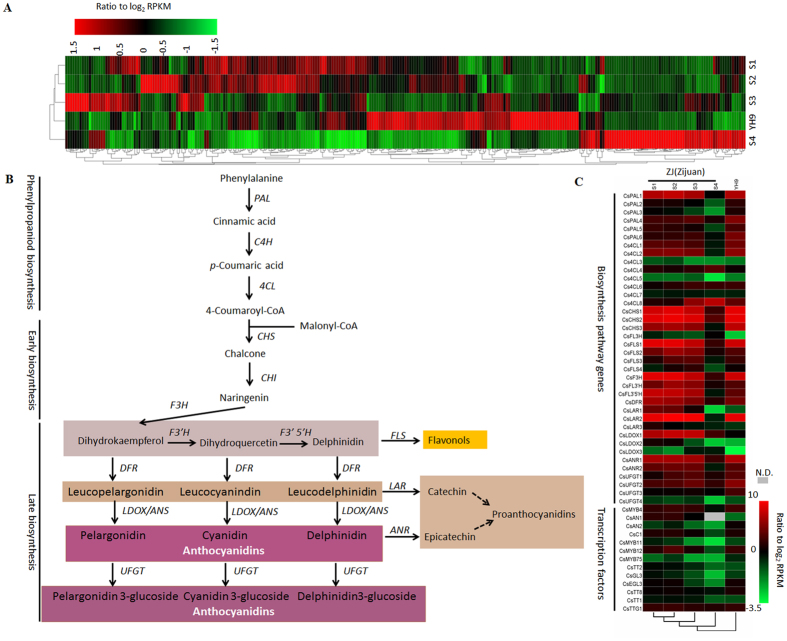

Genes involved in three secondary metabolic pathways (flavonoid biosynthesis, anthocyanin biosynthesis, and flavone and flavonol biosynthesis pathways) that are related to foliage pigmentation were analyzed using C. sinensis transcript unigenes. By mapping to the KEGG reference pathways, a total of 308 unigenes were assigned to the three pathways (Fig. 2A). We examined the expression levels of anthocyanin structural genes and found no significant difference in early biosynthetic genes (EBGs). However, the LBGs CsF3′H, CsF3′5′H, CsDFR1, CsDFR2, CsLDOX1, CsLDOX2 and CsLDOX3 showed 12.7-, 6.49-, 2.3-, 10.7-, 36.4-, 37.9- and 7.9-fold higher levels of expression, respectively, in purple-colored foliage than in the corresponding green-colored foliage (Fig. 2B,C). In addition, CsLAR1, CsLAR2, and CsLAR3, which encode enzymes for catechin biosynthesis, were highly expressed in red foliage, whereas their transcripts were almost undetectable in green foliage (Fig. 2B,C). Moreover, the expression level of anthocyanin LBGs was significantly upregulated in young ‘ZJ’ tea leaves (Fig. 2C). The result was also validated by real time qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. S1). This result demonstrated that accumulation of anthocyanin in tea foliage is regulated at the transcriptional level.

Figure 2. Analysis of transcription data obtained from C. sinensis cultivars ‘ZJ’ and ‘YH9’.

(A) Hierarchical clustering analysis of 308 phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathway related transcripts unigenes based on RNA-seq profiles data. (B) Simplified model of the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in tea plant. (C) Phenylpropanoid and flavonoids pathway with related transcripts present in ‘ZJ’ and ‘YH9’, respectively. N.D., undetected.

Flavonoid biosynthesis is regulated by the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) transcriptional complex. In particular, a subgroup of R2R3-MYB characterized by the presence of the bHLH interacting signature ([DE]Lx2[RK]x3Lx6Lx3R) in the R2R3 domain and a C-terminus KPRPR[S/T]F motif that is typical of anthocyanin regulators has been well documented in the literature22,23. Therefore, we investigated anthocyanin biosynthesis-related MYB, bHLH, and WD40 TFs in the C. sinensis transcriptome. Of these unigenes, c45468_g1_i1 and c59852_g1_i1 were designated as anthocyanin1 (CsAN1) and anthocyanin2 (CsAN2), respectively; they encode TFs homologous to AtMYB113 from Arabidopsis, which is related to anthocyanin biosynthesis. In the stage S2 foliage, only CsAN1 showed 19.4-fold higher expression in red foliage than in green foliage, while no significant difference was observed in CsAN2 (Fig. 2C). Moreover, compared with mature leaves, CsAN1 expression was markedly upregulated in young leaves and was highly correlated with transcript levels of anthocyanin LBGs, which is consistent with the tissue-specific pattern of anthocyanin accumulation in ‘ZJ’ tea plants.

We also investigated anthocyanin biosynthesis-related bHLH TFs and WD-repeat genes in the C. sinensis leaf transcriptome. Two homologues of AtGL3 and AtEGL3 (CsGL3 and CsEGL3) and a homologue of AtTTG1 (CsTTG1) were identified. CsGL3 had 1.7-fold higher expression levels in stage S2 purple foliage than in the corresponding green foliage (Fig. 2C). By contrast, the CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 expression levels were not significantly different between red and green foliage (Fig. 2C), which is consistent with our real time qRT-PCR results (Fig. S1).

Taken together, the results suggest that CsAN1 is the candidate gene controlling levels of anthocyanin accumulation in ‘ZJ’ tea.

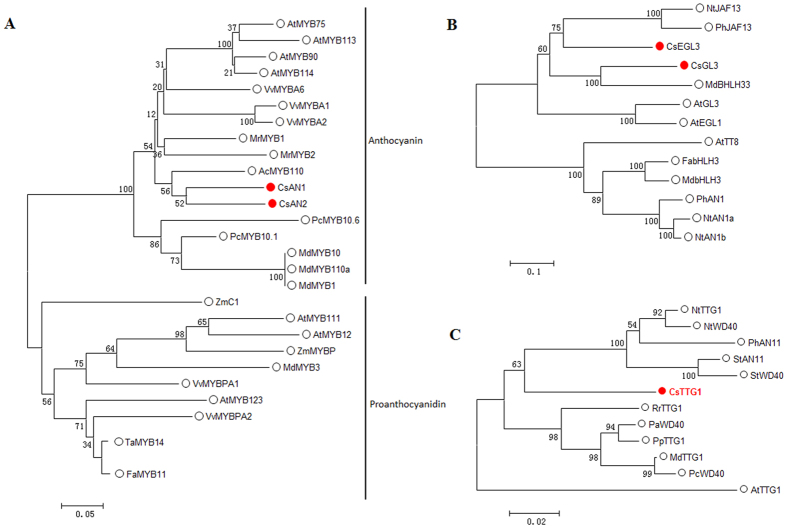

Phylogenetic analysis of the identified C. sinensis transcriptional regulators

Phylogenetic analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences using the neighbor-joining method was employed to determine the relationships that may exist between the identified C. sinensis MYB, bHLH and WD40-repeat regulatory proteins and known TF genes. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that CsAN1 and CsAN2 are most similar to the Actinidia chinensis anthocyanin regulatory TF AcMYB110 and share 58% and 56% identity, respectively. Sequence alignment indicated that CsAN1 and CsAN2 have a bHLH interacting signature (Fig. S2). The CsGL3 amino acid sequence is very similar to MdbHLH33 from apple (61% identity), while the CsEGL3 amino acid sequence shares 52.6% identity with Nicotiana tabacum NtJAF13 (Fig. 3B; Fig. S3). Finally, CsTTG1 displays very high similarity to its homologues from Nicotiana tabacum, NtTTG1, and Petunia hybrid, PhAN11 (Fig. 3C; Fig. S4).

Figure 3. Identification of putative transcriptional regulators involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in tea.

Schematic representation of the phylogenetic relationships existing between the tea MYB (A), basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) (B) and TTG1-like (C) proteins isolated and used in this study with their closest homologues. Sequences were aligned using Clustal X and phylogeny reconstruction was done using the neighbour-joining method and tested using the bootstrap method with 1000 replicates. Both alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed using MEGA version 7.

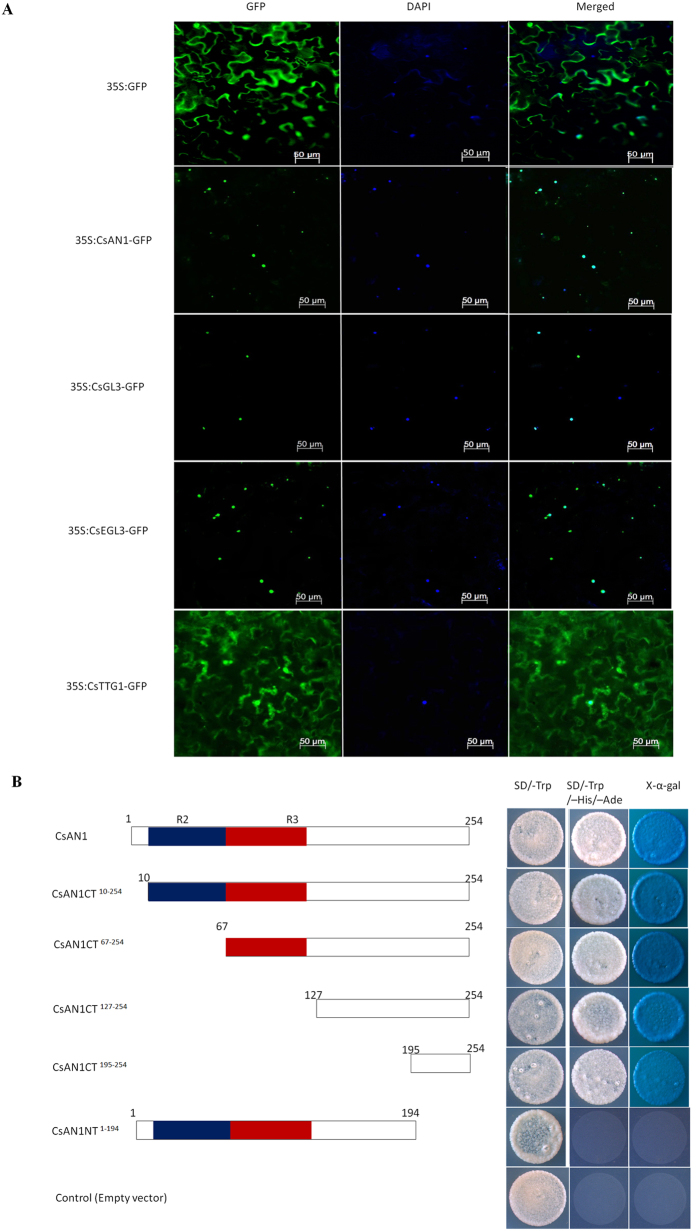

Sub-cellular localization of the CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3, CsTTG1 proteins and transcriptional activity analysis of CsAN1

To determine the subcellular localization of the TFs identified in this work, the full-length coding sequences of each respective TF were fused in frame with the GFP gene. These constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 and then infiltrated in N. benthamiana leaves; the fluorescence signals were examined in epidermal cells. As shown in Fig. 4, 35S:GFP proteins were localized in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, whereas the 35S:CsAN1-GFP, 35S:CsGL3-GFP and 35S:CsEGL3-GFP fusion proteins were exclusively localized in the nucleus (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the fluorescence of 35S:CsTTG1-GFP was not targeted exclusively to the nucleus, and the GFP signal was found in the cytoplasm and cell membrane (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4. Subcellular localizations of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 and transactivation assay of CsAN1.

(A) Subcellular localization of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 in epidermal cells of N. benthamiana leaves. GFP fluorescence was detected 50 hours after infiltration. The nuclei were indicated by DAPI staining. (B) Transactivation assay of CsAN1. Either the full length or a truncated ORF of CsAN1 was fused with pGBKT7, and transformed yeasts were selected on SD/-Trp or SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade/X-α-gal media for 3 d at 30 °C. Transcription activation was monitored by the detection of yeast growth and an α-galactosidase assay.

The R2R3-MYB TF CsAN1 is significantly upregulated in purple foliage and localized to the nucleus, implying that it may act as a transcription activator. A transactivation assay indicated that only transformants of pGBKT7 that were fused with the full-length CsAN1 ORF (covering 1–254 aa) or truncated CsAN1 ORF fragments expressing C-terminal amino acid sequences (covering 10–254 aa, 67–254 aa, 127–254 aa and 195–254 aa, respectively) grew well in SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade and showed α-galactosidase activity. Truncated CsAN1 ORF fragments expressing N-terminal amino acid sequences (covering 1–194 aa) or pGBKT7 (negative control) showed no α-galactosidase activity (Fig. 4B). These assays indicated that CsAN1 has transactivation activity, which is attributed to the C-terminal 195–254 residues.

CsAN1 associates with the CsLDOX1 and CsLDOX2 promoters

MYB TFs specially bind to the so-called MYB binding site (MBS). Sequence analysis identified MBS elements in the promoters of CsLDOX1 and CsLDOX2 (Fig. S5A), suggesting that they might be the direct targets of CsAN1. Y1H assays were performed to test the association of CsAN1 with the CsLDOX1 and CsLDOX2 promoters. The results showed that CsAN1 binds to the promoters of CsLDOX1 and CsLDOX2 (Fig. S5B), supporting the hypothesis that CsAN1 is the TF regulating the expression of CsLDOX1 and CsLDOX2.

CsGL3 and CsEGL3 modulate the intracellular localization of CsTTG1

CsTTG1-GFP was typically found in the cytoplasm and nucleus of epidermal cells (Fig. 4A; Fig. S6D). This intracellular localization appears to be altered in tobacco plants overexpressing CsGL3 and CsEGL3. However, cells co-expressing 35S:CsGL3 or 35S:CsEGL3 with CsTTG1-GFP accumulated GFP mainly in the nucleus (Fig. S6E,F). As a negative control, GFP distribution in wild type, CsGL3-overexpressing and CsEGL3-overexpressing lines appears to be throughout N. benthamiana epidermal cells (Fig. S6A–C). Taken together, we hypothesized that the intracellular localization of CsTTG1 depends partly on the bHLH proteins CsGL3 and CsEGL3 in a partially redundant manner. This result revealed that two bHLH TFs may recruit CsTTG1 to form the MYB-bHLH-WDR (MBW) complex that synergistically controls expression.

CsAN1 and CsTTG1 interact with CsGL3 or CsEGL3 to form a MYB/bHLH/WD-repeat (MBW) protein complex

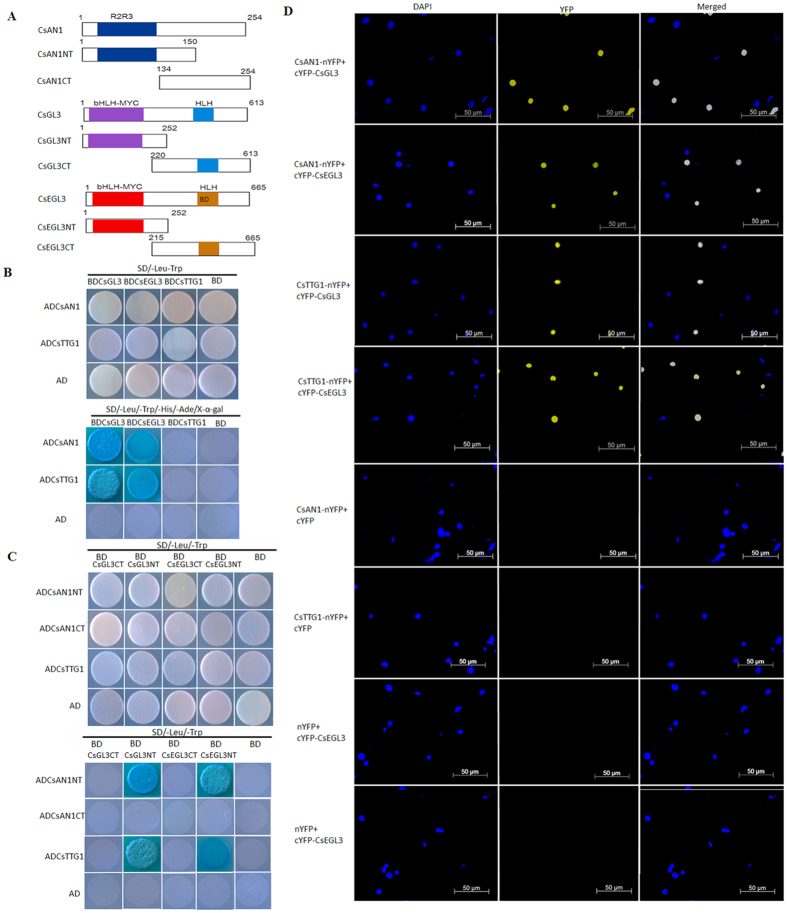

To investigate whether CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 form a MBW complex to regulate anthocyanin accumulation Y2H was used (Fig. 5A). We found that CsAN1 interacts with CsGL3 and CsEGL3, but not with CsTTG1 (Fig. 5B). Similarly, CsTTG1 interacts with CsGL3 and CsEGL3 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. CsAN1 and CsTTG1 interact with CsGL3 and CsEGL3.

(A) Schematic diagram of CsAN1, CsGL3 and CsEGL3 domain constructs. (B) Y2H assays show that CsAN1 and CsTTG1 interact with CsGL3 and CsEGL3 in yeast. (C) Y2H assays show that CsAN1NT and CsTTG1 interact with CsGL3NT and CsEGL3NT in yeast. (D) BiFC assay to detect the interactions of CsAN1 and CsTTG1 (fused with N-terminal fragment of YFP) with CsEGL3, CsGL3 (fused with C-terminal fragment of YFP). Construct pairs indicated on the left were co-expressed in leaves of N. benthamiana and and visualized using confocal microscopy. Expressions of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3, CsEGL3 or CsTTG1 alone were used as negative controls. YFP fluorescence was detected 50 h after infiltration. The nuclei are indicated by DAPI staining.

We examined which domains of CsGL3 and CsEGL3 in the MYB/bHLH/WD-repeat complex are responsible for interacting with the CsAN1 and CsTTG1 proteins. The bHLH members (CsGL3 and CsEGL3) were divided into N-terminal fragments (CsGL3NT and CsEGL3NT) containing a bHLH-MYC binding domain and C-terminal fragments (CsGL3CT and CsEGL3CT) containing the bHLH DNA binding domain (Fig. 5A). CsAN1 was similarly divided into N-terminal fragments containing the R2R3 DNA binding domain and C-terminal fragments to produce CsAN1NT and CsAN1CT (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5C, the bHLH member N-terminal fragments (CsGL3NT and CsEGL3NT), but not the C-terminal fragments (CsGL3CT and CsEGL3CT), of these transcription factors exhibited interactions with CsAN1NT and CsTTG1 in yeast. These results suggest that the N-terminal domains of CsGL3 and CsEGL3 are responsible for the interaction with CsAN1 and CsTTG1.

We next adopted BiFC assays24 to verify the interactions of CsAN1 and CsTTG1 proteins with CsGL3 and CsEGL3 in planta. The N-terminal fragment of yellow fluorescent protein (nYFP) was ligated with CsAN1 and CsTTG1 to produce CsAN1-nYFP and CsTTG1-nYFP. CsGL3 and CsEGL3 were individually fused with the C-terminal fragment of YFP (cYFP). CsAN1-nYFP and CsTTG1-nYFP were transiently co-expressed with cYFP-CsGL3 or cYFP-CsEGL3 in N. benthamiana leaves. We found that co-expression of CsAN1-nYFP with cYFP-CsGL3 or cYFP-CsEGL3 resulted in strong YFP fluorescence in the nuclei of epidermal cells in N. benthamiana leaves (Fig. 5D). Similar results were observed for co-expression of CsTTG1-nYFP with cYFP-CsGL3 or cYFP-CsEGL3 (Fig. 5D). In contrast, co-expression with the negative control combinations failed to generate YFP fluorescence.

Collectively, these results implied that CsAN1 and CsTTG1 proteins physically interact with the bHLH to form a MYB/bHLH/WD-repeat complex.

CsLDOX2 promoter activity is regulated by MBW protein complexes

To predict the transcriptional regulatory roles of MBW protein complexes, a dual luciferase assay with the CsLDOX2 promoter was used in this study. Based on the results, compared to the empty vector, CsAN1 induced an approximately 4.2-fold increase in CsLDOX2 promoter activity (Fig. S7A). When co-expressed with CsAN1, CsGL3 or CsEGL3 showed a significant synergistic effect, and CsLDOX2 promoter activity was stimulated over 25.6- and 13.2-fold, respectively (Fig. S7B). Moreover, the highest activity, an approximately 40-fold increase, was observed when CsAN1, CsTTG1 and CsGL3 were transformed simultaneously. emphasizing the fact that these three proteins act together to activate their target promoters.

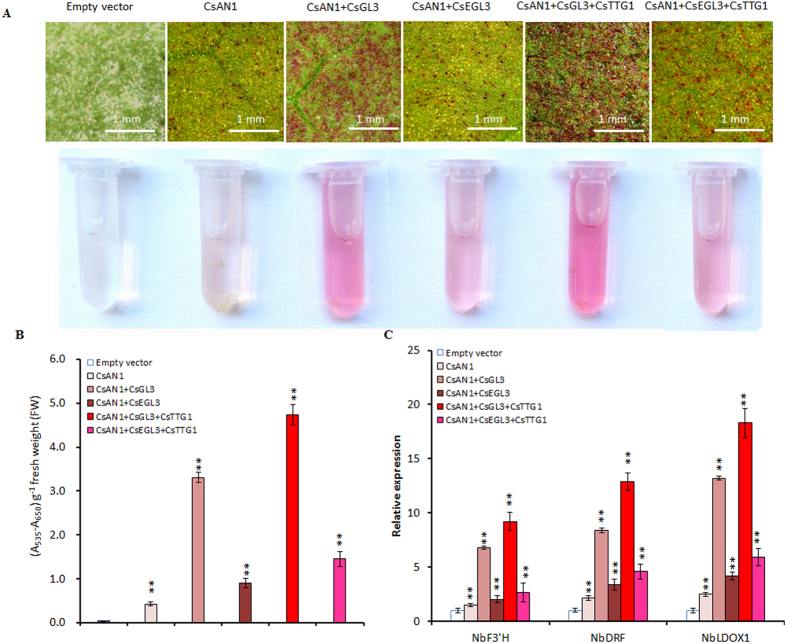

Altered MBW complex gene expression changes anthocyanin accumulation in plants

For MBW-induced anthocyanin pigment accumulation in N. benthamiana, CsAN1, CsAN1/CsGL3, CsAN1/CsEGL3, CsAN1/CsGL3/CsTTG1 and CsAN1/CsEGL3/CsTTG1 were syringe-infiltrated into the underside of expanding tobacco leaves. Pigmentation was evident at the infiltration points as early as 4 days post-infiltration for CsAN1/CsGL3/CsTTG1. The degree of pigmentation gradually increased over the experimental period of up to 10 days (Fig. 6A). However, no coloring was observed at the infiltration sites 10 days after transformation with empty vector (Fig. 6A). Consistent with the visual assessment of red pigmentation, leaves collected at 10 days post-infiltration had undetectable levels of anthocyanin in leaf disks infiltrated with empty vector and different levels in leaf disks infiltrated with CsAN1 and CsGL3 or CsEGL3, CsAN1 and CsTTG1, CsGL3 or CsEGL3 (Fig. 6A,B).

Figure 6. Transient overexpression of C. sinensis MBW complex genes induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in N. benthamiana leaves.

(A) N. benthamiana leaves in 10 days after transformation with: Empty vector, CsAN1, CsAN1 + CsGL3, CsAN1 + CsEGL3, CsAN1 + CsGL3 + CsTTG1 and CsAN1 + CsEGL3 + CsTTG1, respectively. (B) Anthocyanin contents as shown in (A). (C) Expression levels of NbF3′H (AB289449), NbDFR (AB289448) and NbLDOX1 (AB723683) in N. benthamiana leaves transformed with indicated vectors. Error bars are the SD for five replicate reactions. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.01) by Student’s t-test.

To elucidate the molecular mechanism behind this effect of C. sinensis MBW complex on anthocyanin biosynthesis in tobacco, a transcript accumulation study of MBW genes and anthocyanin LBGs was performed using quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The results revealed that the expression levels of MBW-related genes were not significantly different when infiltrated alone or co-infiltrated with its partners, whereas LBG transcript accumulation was slightly increased when infiltrated with CsAN1 alone compared with the empty vector (Fig. 6C; Fig. S8). Co-expression of CsAN1/CsGL3 or CsAN1/CsGL3/CsTTG1 resulted in higher transcript levels of anthocyanin LBGs than in the corresponding leaf disks infiltrated with CsAN1/CsEGL3 or CsAN1/CsEGL3/CsTTG1, consistent with the measured anthocyanin content (Fig. 6C).

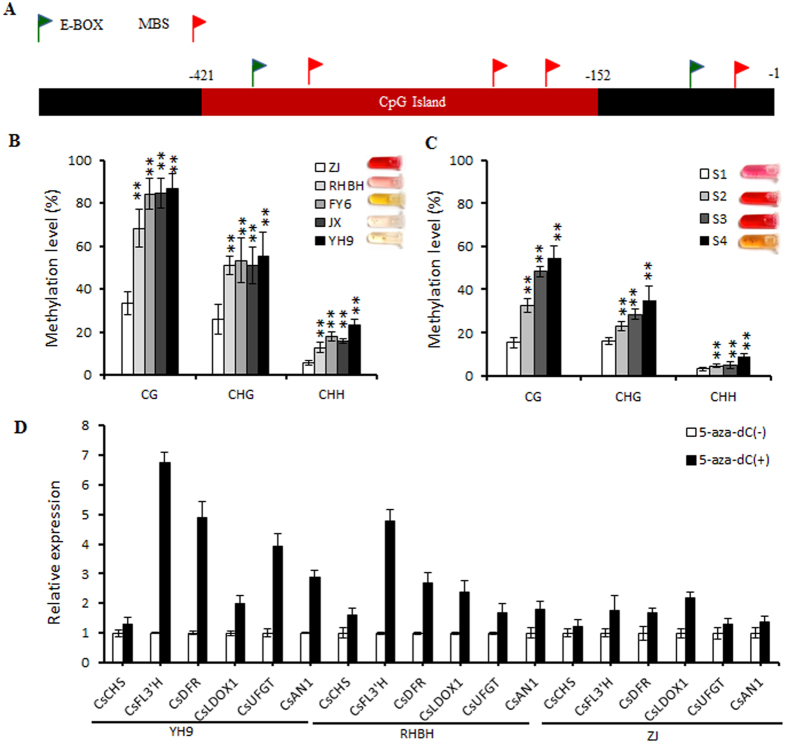

Hypomethylation of the CsAN1 promoter resulted in higher expression in purple-colored foliage

To investigate the molecular basis of the higher expression levels of CsAN1 in the purple foliage of tea, the promoter of CsAN1 was isolated from ‘ZJ’, ‘RHBH’, ‘FY6’ and ‘YH9’. We sequenced the PCR products of each of these fragments from three independent reactions in the four cultivars. The promoters contained a minisatellite polymorphism (SSR) and showed limited variation between the cultivars (Fig. S9A). Interestingly, further analysis indicated that these promoters contained Gypsy-18 and SZ-67 elements (Fig. S9B), both of which are class I long terminal repeat retrotransposons. These elements may attract epigenetic changes to activate or deactivate adjacent host genes.

To verify this hypothesis, we analyzed the methylation levels of cytosine in the CsAN1 promoter of green and purple foliage tea cultivars by bisulfite sequencing (BSP)-PCR. The methylation levels of the CG, CHG, and CHH cytosines (where H is A, C or T) in the CpG island of the CsAN1 promoter (5′ upstream of start codon -152 to -421) were significantly decreased in the high anthocyanin cultivars compared to the low anthocyanin cultivars (Fig. 7B). Moreover, to examine whether there is alteration in the dynamics of methylation in the CsAN1 promoter during leaf development, the methylation activity of the CpG island was assessed in the ‘ZJ’ leaf during the four stages using the bisulfite sequencing approach. The results demonstrated that ‘ZJ’ exhibited markedly different methylation levels during leaf development. The methylation levels of cytosine progressively increased with leaf maturation, resulting in a high methylation level in stage S4 leaves (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. DNA methylation analysis of the CsAN1 promoter.

(A) Schematic representation of CsAN1 promoter. Red box indicate CpG island. (B) DNA methylation status of bisulfite-sequenced CpG island in five tea cultivars and (C) ‘ZJ’ leaf at four developmental stages. CG, CHG and CHH refer to the three different contexts of cytosines, in which H represents nucleotide A, C or T. Each data point represents a mean ± SD of three independent gDNA extractions with three independent technical replicates. Five independent clones from each reaction were sequenced and analyzed. (D) Real-time reverse transcription-PCR analyses of CsAN1 and anthocyanin biosynthesis related genes expression in ‘YH9’, ‘RHBH’ and ‘ZJ’ leaves treated with (+) or without (−) 5-aza-dC, an inhibitor of DNA methylation. Tea Actin was used as a control. Values are means ± SD of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences (p < 0.01) by Student’s t-test.

To further confirm whether the ectopic expression of CsAN1 results in hypomethylation of the promoter region, we treated the tea plants with 5-aza-2′ deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC), an inhibitor of DNA methylation25. Treatment with 5-aza-dC increased the expression of CsAN1 2.88-fold in ‘YH9’, 1.79-fold in ‘RHBH’ and 1.39-fold in ‘ZJ’, leading to activation of anthocyanin LBG expression (Fig. 7D). These results indicate that DNA methylation in the 5′ upstream sequence of CsAN1 plays an essential role in the regulation of CsAN1 expression.

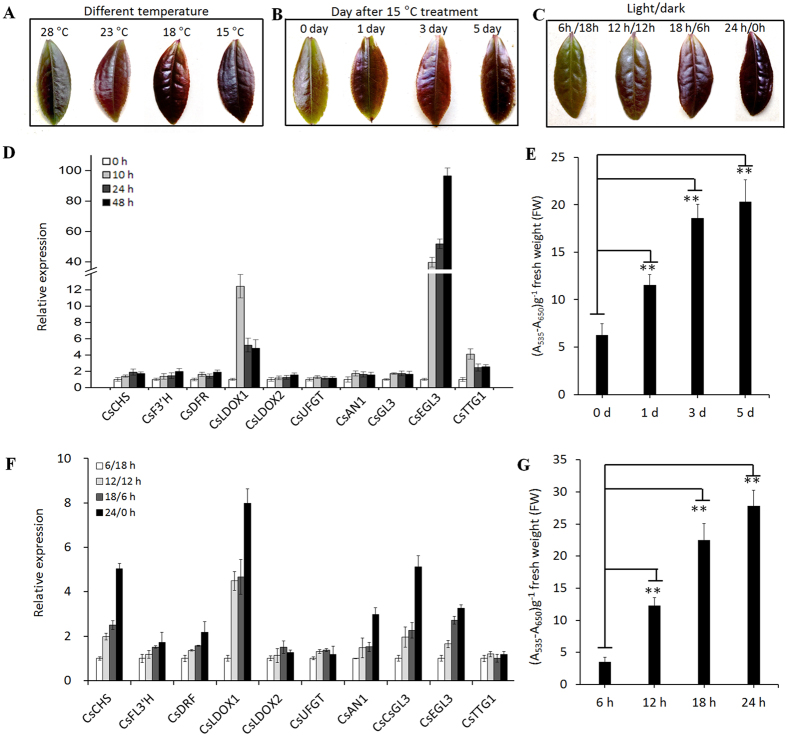

Temperature and light alter the expression of the MBW complex and anthocyanin biosynthetic genes

Under a high temperature of 28 °C, ZJ tea leaves showed only slight red pigmentation indicating regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis is temperature sensitive. To understand the effect of temperature on coloration and the expression of anthocyanin-related genes in leaves, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ trees were placed at 28 °C, 23 °C, 18 °C, and 15 °C to test the effects of low temperatures. Compared with a high temperature of 28 °C, low temperatures dramatically promoted red coloration in ‘ZJ’ tea leaves (Fig. 8A). In the high temperature treatment of 28 °C, we reset the temperatures as low as 15 °C, without changing the other conditions. The tree leaves showed a significant accumulation of anthocyanin content (Fig. 8B,E). Correspondingly, the gene transcripts of both the anthocyanin biosynthetic genes and the transcriptional activation complex increased (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8. Different environmental conditions alter anthocyanin accumulation by changing the expression of anthocyanin related MBW-complex and biosynthetic genes.

(A) Leaves harvested from the different temperature conditions. (B) Leaves harvested in 1, 3, 5 day after 15 °C treatment plants. (C) The ‘Zijuan’ tea leaves harvested from different photoperiod conditions. (D) The genes expression profile after 15 °C treatment with 0, 10, 24, 48 h. (E) Low temperature (15 °C) increases the accumulation of anthocyanin in leaves. The 0, 1, 3, 5 day indicates anthocyanin levels after 15 °C treatment. (F) The genes expression profile under different photoperiod conditions. (G) The anthocyanin levels under different photoperiod conditions. Error bars on each symbol indicate the mean ± SD of three replicate reactions. Asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.01) between combinations by Student’s t-test.

To understand the effect of light on coloration and the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis-related genes in leaves, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ trees were used to conduct 6-h, 12-h, 18-h and 24-h light period lighting treatments. The leaves displayed marked red pigmentation after 15 days of long light, whereas the 6-h light period leaves remained slightly red colored (Fig. 8C). Accordingly, in comparison with short light, CsAN1, CsGL3 and CsEGL3 expression increased in the long light conditions, and the anthocyanin biosynthetic gene transcripts were increased (Fig. 8F). Thus, longer light periods enhanced anthocyanin biosynthesis and accumulation in leaves (Fig. 8G).

These results indicated that low temperatures and long illumination times promote anthocyanin accumulation due to partial or complete activation of C. sinensis anthocyanin biosynthesis-related MBW gene expression.

Low temperature and a long photoperiod induce CsAN1 promoter demethylation

The transcription of CsAN1 appears to be elevated in response to environmental factors. To examine whether DNA methylation in the CsAN1 promoter is plastic under different environmental factors, the methylation levels of ‘ZJ’ stage S2 leaves were evaluated using the bisulfite sequencing approach. The results demonstrated that ‘ZJ’ exhibited markedly different methylation levels under four different temperature treatments. The methylation levels of cytosine progressively increased with temperature increases, resulting in a high methylation level under 28 °C treatment (Fig. S10A). Moreover, we detected that CsAN1 promoter methylation was altered under different illumination conditions. A high methylation level of the CsAN1 promoter was observed under short light, whereas it was notably decreased when the illumination time was increased (Fig. S10B). Our results indicated that environmental factors regulate ‘ZJ’ tea anthocyanin biosynthesis, which partially occurs through CsAN1 promoter methylation and demethylation.

Discussion

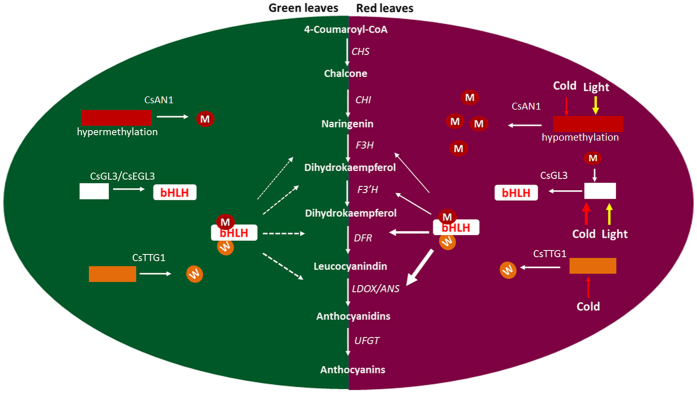

We found that red foliage is associated with high anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 1), which is consistent with increased transcript levels of anthocyanin LBGs, including CsF3′H, CsF3′5′H, CsDFRs and CsLDOXs. This result indicates that a high accumulation of anthocyanin in ‘ZJ’ foliage may be attributed to up-regulation of the R2R3-MYB and/or bHLH genes. The activation of R2R3-MYB TFs leads to the up-regulation of regulators and/or anthocyanin biosynthetic genes that are associated with red pigmentation in many crops, such as apple, peach, pear, purple cauliflower, tomato, plum and crabapple3,5,7,10,13. In this study, we identified two anthocyanin biosynthesis-related R2R3-MYB TFs, but only the CsAN1 homolog of AcMYB110 from Actinidia26 was strongly upregulated in young foliage of the ‘ZJ’ cultivar, indicating that it is a master anthocyanin regulator in ‘ZJ’ tea plants (Fig. 2C; Fig. S1). Interestingly, unlike AcMYB110 control of kiwifruit petal colour pigmentation, the activation of CsAN1 in ‘ZJ’ led to anthocyanin-specific accumulation in young leaves and stems but not in flowers, indicating that its function varies in different species. We also detected evidence of increased transcript levels of CsGL3, suggesting that, in tea, CsGL3 is positively regulated by CsAN1 (Fig. 2; Fig. S1). Although the expression of MdMYB10 does not increase the expression of a bHLH TF in apple5, AtMYB75 regulates the expression of AtTT8 in Arabidopsis27, while its homologous gene BoMYB2 appears to strongly upregulate its bHLH interactor BobHLH1 in cauliflower7. Similarly, AN2 and AN4, two genes encoding MYB transcription factors, activate the AN1 bHLH TF in petunia28. Our results demonstrate that CsAN1 and CsGL3 likely function together to coordinately regulate several transcripts of anthocyanin LBGs to confer anthocyanin accumulation in the purple foliage of ‘ZJ’ tea (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Model showing the molecular mechanism of the purple-coloration in Camellia sinensis foliage.

The hypomethylation of the CsAN1 promoter activated the expression of CsAN1. CsAN1 interact with CsGL3 to recruits CsTTG1 to form MBW protein complexe, subsequently activation the expression of anthocyanin LBGs. Environment factors, low temperature and long-photoperiod activation expression of MBW protein complex, which significantly activating on the anthocyanin pathway. As a result, the biosynthesis of anthocyanin is greatly increased, causing the purple-coloration.

The activity of MYB-like genes has been suggested to be the primary cause of natural variation in anthocyanin pigmentation in plants16. The gain or loss of function of the master anthocyanin regulator MYB always disrupts anthocyanin accumulation, and these changes can be caused by sequence mutations in the MYB coding or promoter regions16,17,18,29 or by DNA methylation or demethylation in the promoter15,17,30. In this study, the CsAN1 promoter showed limited variation between varieties, but this variation cannot explain the phenotype between green foliage and red foliage in tea plants. However, a methylation analysis of the CsAN1 promoter revealed that the methylation level of the CpG island was inversely correlated with the CsAN1 expression level and anthocyanin content, indicating that a low methylation level of the CsAN1 promoter in ‘ZJ’ may confer intense anthocyanin accumulation (Fig. 7). Similar hypermethylation in the MYB promoter of the anthocyanin regulators MzP1 in Zea mays, PcMYB10 in Pyrus, and MdMYB10 in Malus domestica are also associated with low anthocyanin content15,17,30,31. While other studies have investigated MYB hypermethylation15,17,30, the relationship of MYB methylation in the CsAN1 clade to the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in vegetative tissues has not been reported until this study (Fig. 9).

Interestingly, the CsAN1 promoter microsatellite contained many G-rich SP1-like elements that inhibit CpG methylation32,33. The Gypsy LTR retrotransposon element in the CsAN1 promoter may attract epigenetic changes to regulate neighboring gene expression. In Arabidopsis, regulation of DNA methylation of transposable elements and tandem repeats contributes to the regulation of adjacent host gene expression34,35. In this study, promoter retrotransposon methylation and demethylation may associate with CsAN1 expression, with the mechanism underlying this being of interest for further work.

The biosynthesis of pigments in many plants is affected by environmental conditions36,37. Numerous studies have shown that light, temperature and phytohormones can affect the expression of anthocyanin regulators and structural genes23,27,38,39. In apples, high temperature decreases anthocyanin content and down-regulates flavonoid biosynthesis and MdMYB10 gene expression23. In contrast, low environmental temperatures promote anthocyanin accumulation in apple by up-regulating the expression of MdbHLH3 in the MdMYB1 transcriptional complex40. Light significantly increases the accumulation of flavonoids, and the expression of their biosynthetic genes has been partly elucidated38. Arabidopsis AtMYB75, Arabidopsis AtMYB90 and its homologous gene MdMYB1 in apple are crucial regulators of light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis, and their degradation requires the CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1) ubiquitin-dependent pathway in the dark41,42. Similarly, several recent reports have described jasmonate-mediated anthocyanin accumulation through upstream control of MBW complex activity39,43. However, these studies do not fully explain the underlying mechanism of up-regulation and down-regulation of anthocyanin regulators in specific environmental conditions. It was reported that cold-induced expression of maize ZmMI1 results in severe demethylation in core promoter regions44. In this study, we found that the promoter DNA methylation levels of the anthocyanin master regulator CsAN1 were highly plastic to different environmental factors. Interestingly, the CsAN1 promoter comprises numerous cis-acting elements, including MYB-, MYC-recognizing sites, light-responsive elements, and phytohormone-responsive elements within the retrotransposon, which may potentially be involved in regulating the CsAN1 response to different environmental circumstances. This result suggested that methylation and demethylation within the cis-acting elements may not only regulate the binding of relevant transcription factors but also affect the environmental response (Fig. S10).

In addition to CsAN1, we found that low temperatures increased the expression of CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1, while long light periods increased the transcription of CsGL3 and CsEGL3 but not CsTTG1. Under both low temperatures and long illumination periods, the transcription of CsLDOX1 was markedly elevated. The link between environmental conditions affecting anthocyanin accumulation and the transcription levels of the corresponding genes indicated that the anthocyanin-related MBW genes and CsLDOX1 are pivotal in the anthocyanin pathway.

Materials and Methods

Anthocyanin measurement

Three-year-old C. sinensis plant leaves were obtained from the tea garden of South China Agricultural University and used for the analysis of anthocyanin content. Anthocyanin was measured as described previously40. The pre-weighed sample leaves were placed into a 1 ml extraction buffer (18% 1-propanol, 1% HCl, and 81% water), boiled for 3 minutes and then incubated in darkness overnight at room temperature. Two absorbencies (A535 and A650) of the extracts were measured spectrophotometrically. The amount of anthocyanin was reported as (A535–A650) g−1 fresh weight (FW).

HPLC analysis

The indicated samples (approximately 0.5 g fresh weight) as shown in the results were extracted with 5 mL of methanol/water/acetic acid (85: 15: 1) extract solution in a test tube at 4 °C in the dark for 72 h, with shaking every 6 h. The anthocyanin standards (Sigma-Aldrich) or tea samples were injected into an XSelect HSS C-18 SB column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Waters Technologies) and separated using 5% formic acid (A) and 100% methanol (B) as mobile phases on a Waters Alliance series HPLC system. Detection was performed at 520 nm for anthocyanin45.

RNA-seq, de novo assembly, and sequence analysis

Total RNA was extracted at four different stages from ‘ZJ’: buds (S1), 7 DBA (S2), 15 DBA (S3), and 40 DBA (S4); total RNA was extracted from the foliage at S2 for ‘YH9’ (the Yunnan Daye cultivar), which was the same as that used for measuring the anthocyanin content. The cDNA library was sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform, and the results were analyzed by the Annoroad Gene Technology Corporation (Beijing, China).

Isolation of genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis and phylogenetic analysis

For identifying anthocyanin biosynthetic structural genes and regulators from the transcriptome database, we began with simple keyword searches and confirmed each search result with BLAST searches. The ORFs of the anthocyanin biosynthetic regulators were cloned by PCR. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 7 through the neighbor-joining method, and sequence alignment was performed using the CLUSTAL X program. The gene accession IDs are: CsAN1 (KU745295), CsAN2 (1896250) PcMYB10.1 (AKV89247), PcMYB10.6 (KP772286.1), AcMYB110a (AHY00342), MdMYB1 (ADQ27443.1), MdMYB3 (AEX08668), MdMYB10 (ACQ45201.1), MdMYB110a (BAM84362.1), AtMYB90/PAP2 (75338996), AtMYB75/PAP1 (75333682), AtMYB123/TT2 (27151707), AtMYB113 (Q9FNV9), AtMYB114 (Q9FNV8.1), VvMYBA1 (BAD18977), PcMYB10.6 (AKV89252.1), PcMYB10.1 (AKV89247.1), MrMYB1 (ADG21957), MrMYB2 (ADG21958), TaMYB14 (AFJ53059), FaMYB11 (AFL02461), VvMYBPA1 (NP_001268160), VvMYBPA2 (ACK56131), ZmMYBP (NP_001278607), ZmC1 (1613412E), NtJAF13 (AHY00341), PhJAF13 (AAC39455.1), AtGL3 (75309232), AtEGL3 (34222624), MdbHLH33 (ABB84474.1), MdbHLH3 (ADL36597), PhAN1 (AAG25928.1), NtAN1a (AEE99257.1), NtAN1(AEE99258.1), AtTT8 (Q9FT81.2), FabHLH3 (AFL02463.1), AtTTG1 (CAB45372.1), MdTTG1 (ADI58760.1), NtTTG1 (ACJ06978.1), NtWD40 (AIU39032.1), PhAN11 (AAC18914.1), StAN11 (AEF01097.1), StWD40 (AGC31678.1), and FaTTG1 (AFL02466.1).

Real time qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from tissues as indicated in the figures, and 1 μg of RNA from each sample was used for the reverse transcription reaction using a PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit with gDNA eraser (Takara, Japan). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed on a LightCycler 480 Real-Time PCR System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche); the qPCR program was performed as described previously46. As an internal control, the Actin transcript was used to quantify the relative transcript levels of each target gene in each sample. The values represent the mean of three biological replicates.

Subcellular localization

The coding sequences of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 were cloned into a pEGFP vector for fusion with enhanced GFP under control of the 35S promoter to generate the 35S: CsAN1-GFP, 35S:CsGL3-GFP, 35S:CsEGL3-GFP and 35S:CsTTG1-GFP constructs, respectively. Agrobacterium containing the indicated constructs was resuspended in infiltration buffer (0.2 mM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM MES, and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves using a needleless syringe. After infiltration, plants were stored at 24 °C for 50 h before GFP detection. To stain the nuclei, 10 μg/mL 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves 2 h before the observation point.

Induction of anthocyanins by transient transformation of tobacco

Two-week-old seedlings of N. benthamiana grown in a greenhouse were used for infiltration. Agrobacterium strain GV3101 was selected for the transient assay. Separate strains containing CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 fused to the 35S promoter were cloned into the pBI121 vector. Infiltrations comprising the indicated constructs were infiltrated into the abaxial leaf surface. Each infiltration was performed using three leaves on the same plants, and at least ten plants were used for the analysis. For expression analysis, RNA was isolated from the N. benthamiana leaves at 4 days after infiltration. The anthocyanin content was measured after 10 days as described above.

Isolation and identification of the CsAN1 gene promoters

The promoter region of CsAN1 was isolated using hiTAIL-PCR as described previously47. The analysis of the promoter cis-elements was performed using the online software PlantCARE (bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare) and Place (www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/index).

Transactivation assay of CsAN1

The full length CsAN1 ORF and a series of truncated ORF fragments were amplified using specific primers that flanked both termini of each full length/truncated sequence (Table S1), and these amplified sequences were inserted into the pGBKT7 vector (Clontech). Each of the positive plasmids and an insert-less vector were transformed separately into the AH109 yeast strain (Clontech), according to the supplier’s protocol. Yeast colonies growing in SD/-Trp medium were transferred to SD/-Trp/-His/-Ade/X-α-gal medium after 3 d of culture at 30 °C, and the transactivation activity of each protein was evaluated according to their growth status and the activity of α-galactosidase.

Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assay

Y1H assays were performed using the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid System Kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The CsAN1 gene was ligated to pGADT7 to generate the AD-CsAN1 construct. Fragments of the CsLDOX1and CsLDOX2 promoters were ligated to the pAbAi vector to generate pAbAi-bait plasmids, which were then linearized, transformed into the AH109 yeast strain, and selected with a selective synthetic dextrose medium lacking uracil. The AD-CsAN1 constructs were transformed into the AH109 strain containing pAbAi-bait and screened on an SD/-Leu plate containing 250 ng/ml Aureobasidin A (AbA).

Dual luciferase assay of transiently transformed N. benthamiana leaves

A fragment containing 812 bp upstream of the ATG of the CsLDOX2 gene (AB074485) was isolated and inserted into the cloning site of pGreenII 0800-LUC. Transient transformation of the promoter-LUC fusion and luminescence measurements were performed as described previously11.

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay

For the Y2H assay, all the CDS of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3, CsTTG1 and their domain derivatives were cloned into pGADT7 or pGBKT7 vectors. Primers used for the vector construction are presented in Table S1. The Gold Yeast Two-Hybrid System was used for Y2H, according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Clontech). Y2H images were taken 4 days after incubation at 30 °C.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays

For BiFC assays, full-length coding sequences of CsAN1, CsGL3, CsEGL3 and CsTTG1 were cloned into the binary pSPYNE or pSPYCE vector using a ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocols (Vazyme). Primers used to generate the constructs are listed in Table S1. The GV3101 Agrobacterium strains with the indicated pSPYNE or pSPYCE vectors were incubated, harvested, and resuspended in infiltration buffer (0.2 mM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM MES). Equal concentrations and volumes of Agrobacterium strains were mixed and co-infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves using a needleless syringe. After infiltration, the plants were placed at 24 °C for 50 h before observation. The experiments were repeated three times.

Environmental conditions

Temperature treatments were conducted on three-year-old ‘ZJ’ plants, which were grown in a plant growth chamber at 15–28 °C with a 12 h light/12 h dark period and a relative air humidity of 60%. The leaves were harvested 15 days after budding (DAB). For low temperature-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ tea plants were grown in a plant growth chamber under the following conditions: 15 °C and a 12 h photoperiod. All samples were collected at the indicated times after treatment, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

For light treatment, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ trees were grown at 18 °C for 6 h, 12 h, 18 h and 24 h light periods. The leaves were harvested after 15 DAB, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

5-aza-dC treatment

C. sinensis plants were sprayed with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, with or without 5 mM 5-aza-dC (Sigma), and were maintained at room temperature for 48 h in the dark. After treatment for 7 days, stage S2 leaves were sampled for further analysis.

Methylation analysis

BSP-PCR analysis was performed as described previously48. Briefly, 500 ng of genomic DNA from S2 stage leaves was treated with the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research). Using the treated DNA as a template, CsAN1 promoter fragments were amplified using PrimeSTAR Max DNA polymerase (TaKaRa), ligated to the PMD19-T vector (TaKaRa), and then sequenced. Sequences of 15 independent clones of the target fragment were obtained from three independent PCR reactions and analyzed with the online software Kismeth31. The methylation level of each fragment was calculated. To further examine whether the methylation levels are dependent on the leaf development stage, bisulfite sequencing analysis was also performed using gDNA from ‘ZJ’ leaf samples at the four stages as above. Three independent PCR reactions from three different biological replicates were purified and sequenced for analysis.

To further detect whether environmental factors influence CsAN1 promoter methylation, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ tea plants were grown in a plant growth chamber at 15 °C, 18 °C, 23 °C and 28 °C with a 12 h light/12 h dark period and relative air humidity of 60%. The S2 stage leaves were harvested for methylation analysis as described above. To examine whether the methylation was influenced by the photoperiod, three-year-old ‘ZJ’ trees were grown at 18 °C for 6 h, 12 h, 18 h and 24 h light periods. The S2 stage leaves were harvested for further methylation analysis as described above.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Sun, B. et al. Purple foliage coloration in tea (Camellia sinensis L.) arises from activation of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor CsAN1. Sci. Rep. 6, 32534; doi: 10.1038/srep32534 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Science and Technology Agency of Guangdong Province, Runfeng Ecological and Agriculture and Forestry Cooperation of Boluo County, Jiangmen Guopei Biotechnology Limited Company, Yingde Babai Xiucai Tea Limited Company, Guangdong Tieying Agriculture Limited Liability Company for financial support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions B.S., Z.Z. and S.L. conceived the experiments, B.S., Z.Z., X.Z., H.C., Y.M. and Y.W. conducted the experiments, B.S. and Z.Z. taken the photographs, P.C., C.J., C.C., J.L., Y.J., W.M. and S.L. analysed the results, B.S. and Z.Z. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Shi C. Y. et al. Deep sequencing of the Camellia sinensis transcriptome revealed candidate genes for major metabolic pathways of tea-specific compounds. BMC Genomics 12, 131 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Dubos C. & Lepiniec L. Transcriptional control of flavonoid biosynthesis by MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 176–185 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. Transcriptome analysis and transient transformation suggest an ancient duplicated MYB transcription factor as a candidate gene for leaf red coloration in peach. BMC Plant Biol. 14, 388 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelt C., Quattrocchio F., Mol J. & Koes R. ANTHOCYANIN1 of petunia controls pigment synthesis, vacuolar pH, and seed coat development by genetically distinct mechanisms. Plant Cell. 14, 2121–2135 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espley R. V. et al. Red colouration in apple fruit is due to the activity of the MYB transcription factor, MdMYB10. Plant J. 49, 414–427 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A., Zhao M., Leavitt J. M. & Lloyd A. M. Regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway by the TTG1/bHLH/Myb transcriptional complex in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant J. 53, 814–827 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu L. W. et al. The purple cauliflower arises from activation of a MYB transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 154, 1470–1480 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay N. A. & Glover B. J. MYB-bHLH-WD40 protein complex and the evolution of cellular diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 10, 63–70 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borevitz J. O., Xia Y., Blount J., Dixon R. A. & Lamb C. Activation tagging identifies a conserved MYB regulator of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Plant Cell 12, 2383–2394 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews H. et al. Activation tagging in tomato identifies a transcriptional regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis, modification, and transport. Plant Cell 15, 1689–1703 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagné D. et al. An ancient duplication of apple MYB transcription factors is responsible for novel red fruit-flesh phenotypes. Plant Physiol. 161, 225–239 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. H. et al. Activation of anthocyanin biosynthesis by expression of the radish R2R3-MYB transcription factor gene RsMYB1. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 641–653(2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J. et al. McMYB10 regulates coloration via activating McF3′H and later structural genes in ever-red leaf crabapple. Plant Biotechnol. J. 13, 948–961 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. T., Goto-Yamamoto N., Kobayashi S. & Esaka A. Effects of plant hormones and shading on the accumulation of anthocyanins and the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in grape berry skins. Plant Sci. 167, 247–252 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. et al. The methylation of the PcMYB10 promoter is associated with green-skinned sport in Max Red Bartlett pear. Plant Physiol. 162, 885–896 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R. et al. The oil palm VIRESCENS gene controls fruit colour and encodes a R2R3-MYB. Nat. Commun. 5, 4106 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy I., Liang D. & Xu K. Transcriptome analysis of an apple (Malus×domestica) yellow fruit somatic mutation identifies a gene network module highly associated with anthocyanin and epigenetic regulation. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 7359–7376 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espley R. V. et al. Multiple repeats of a promoter segment causes transcription factor autoregulation in red apples. Plant Cell 21, 168–183 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Bao Y. & Huang M. The botanical and quality characteristics of the tea cultivar ‘Zi-Juan’ in Yunnan province. J. Tea 35, 17–18 (2009). (In chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L. et al. Characterization and Activity of Anthocyanins in Zijuan Tea (Camellia sinensis var. kitamura). J. Agr. Food Chem. 61, 3306–3310 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerio L. C., Wachira F. N., Wanyoko J. K. & Rotich M. K. Characterization of anthocyanins in Kenyan teas: Extraction and identification. Food Chem. 131, 31–38 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann I. M., Heim M. A., Weisshaar B. & Uhrig J. F. Comprehensive identification of Arabidopsis thaliana MYB transcription factors interacting with R/B-like BHLH proteins. Plant J. 40, 22–34 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Wang K. et al. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor associated with regulation of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Rosaceae. BMC Plant Biol. 10, 50 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter M. et al. Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 40, 428–438 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christman J. K. 5-Azacytidine and 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine as inhibitors of DNA methylation: mechanistic studies and their implications for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 21, 5483–5495 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser L. G. et al. An R2R3 MYB transcription factor determines red petal colour in an Actinidia (kiwifruit) hybrid population. BMC Genomics 14, 28 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan D. D. et al. Environmental regulation of leaf colour in red 35S:PAP1 Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 182, 102–115 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelt C., Quattrocchio F., Mol J. N. & Koes R. anthocyanin1 of petunia encodes a basic helix-loop-helix protein that directly activates transcription of structural anthocyanin genes. Plant Cell 12, 1619–1631 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi S., Goto-Yamamoto N. & Hirochika H. Retrotransposon-induced mutations in grape skin color. Science. 304, 982 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon R. S. & Chopra S. Progressive loss of DNA methylation releases epigenetic gene silencing from a tandemly repeated maize Myb gene. Genetics. 181, 81–91 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntman E. et al. Kismeth: Analyzer of plant methylation states through bisulfite sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics, 9, 371(2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumber Y. A. et al. An Sp1/Sp3 Binding Polymorphism Confers Methylation Protection. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000162 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson J. et al. VEZF1 elements mediate protection from DNA methylation. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000804 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister J. D. & Gaut B. S. Epigenetic silencing of transposable elements: A trade-off between reduced transposition and deleterious effects on neighboring gene expression. Genome Res. 19, 1419–1428 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin R. K. & Martienssen R. Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat. Rev. Get. 8, 272–285 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellarin S. D. et al. Transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in ripening fruits of grapevine under seasonal water deficit. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1381–1399 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola L. New insights into the regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in fruits. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 477–483 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takos A. M. et al. Light-induced expression of a MYB gene regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples. Plant Physiol. 142, 1216–1232 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T. et al. The Jasmonate-ZIM-domain proteins interact with the WD-Repeat/bHLH/MYB complexes to regulate Jasmonate-mediated anthocyanin accumulation and trichome initiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 23, 1795–1814 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X. B. et al. The bHLH transcription factor MdbHLH3 promotes anthocyanin accumulation and fruit colouration in response to low temperature in apples. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1884–1897 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Y. et al. MdCOP1 ubiquitin E3 ligases interact with MdMYB1 to regulate light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis and red fruit coloration in apple. Plant Physiol. 160, 1011–1022 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A. et al. Light and the E3 ubiquitin ligase COP1/SPA control the protein stability of the MYB transcription factors PAP1 and PAP2 involved in anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 74, 638–651 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An X. H. et al. MdMYB9 and MdMYB11 are involved in the regulation of the JA-induced biosynthesis of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin in apples. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 650–662 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward N., Ito M., Yamaguchi Y., Koizumi N. & Sano H. Periodic DNA methylation in maize nucleosomes and demethylation by environmental stress. Journal Biol. Chem. 277, 37741–37746 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. et al. Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 4069–4075 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. Z. et al. Pyramiding of AtEDT1/HDG11 and Cry2Aa2 into pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) enhances drought tolerance and insect resistance without yield decrease. Plant Cell Tiss. Org. 120, 919–932 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. G. & Chen Y. L. High-efficiency thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR for amplification of unknown flanking sequences. Biotechniques, 43, 649–656 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telias A. et al. Apple skin patterning is associated with differential expression of MYB10. BMC Plant Biol. 11, 93 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.