Abstract

Mental disorders affect a huge number of people and have a major economic impact due to treatment costs and lost productivity. Society and politics need to acknowledge this huge toll in order to better support the healthcare systems that deal with these disorders.

Subject Categories: Neuroscience, S&S: Economics & Business, S&S: Health & Disease

In the EU, about 165 million people are affected each year by mental disorders, mostly anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders 1, 2. Overall, more than 50% of the general population in middle‐ and high‐income countries will suffer from at least one mental disorder at some point in their lives. Mental disorders are therefore by no means limited to a small group of predisposed individuals but are a major public health problem with marked consequences for society. They are related to severe distress and functional impairment—these features are in fact mandatory diagnostic criteria—that can have dramatic consequences not only for those affected but also for their families and their social‐ and work‐related environments 3. In 2010, mental and substance use disorders constituted 10.4% of the global burden of disease and were the leading cause of years lived with disability among all disease groups 2, 4. Moreover, owing to demographic changes and longer life expectancy, the long‐term burden of mental disorders is even expected to increase 3.

In 2010, mental and substance use disorders constituted 10.4% of the global burden of disease and were the leading cause of years lived with disability among all disease groups.

These consequences are not limited to patients and their social environment—they affect the entire social fabric, particularly through economic costs. An adequate estimation of these costs is complex and, owing to incomplete data, difficult to undertake. Moreover, studies on economic costs vary considerably due to deficiencies in the definitions of disorders; populations or samples studied; sources of costs and service utilization; analytical framework; and incomplete cost categories because of lack of data and definitions 5. However, improved epidemiological and economic methods and models together with more complete epidemiological data during the past 20 years now allow the accumulation of comprehensive and increasingly reliable data that give us a good idea about the magnitude of the economic impact of mental disorders.

Mental disorders therefore account for more economic costs than chronic somatic diseases such as cancer or diabetes…

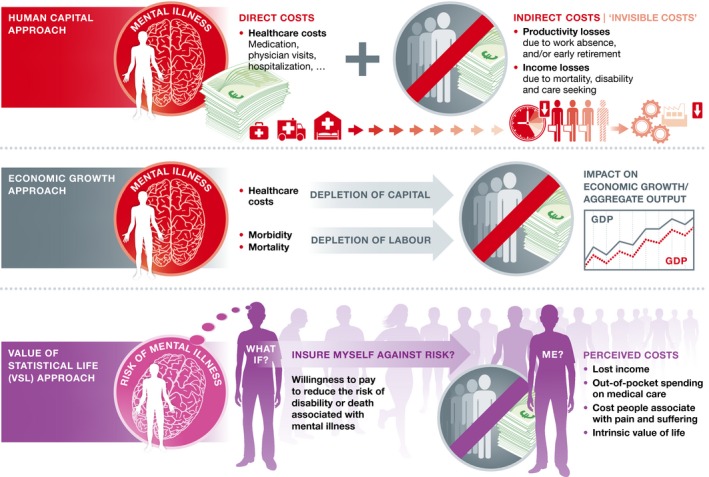

While most people think that medication, visits to a clinic, or hospitalization is a true economic burden of diseases, in reality the burden of disease—and mental disorders in particular—goes far beyond these “direct” diagnostic and treatment costs. In the 2011 report on the global economic burden of non‐communicable diseases 6, the World Economic Forum (WEF) described three different approaches used to quantify economic disease burden, which do not only acknowledge the “hidden costs” of diseases, but also their impact on economic growth at a macroeconomic level (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Different approaches used to estimate economic costs of mental disorders.

Human capital costs

The human capital approach, which is most commonly used to quantify the economic costs of mental disorders and disease in general, distinguishes between direct and indirect costs. Direct costs most often refer to the “visible costs” associated with diagnosis and treatment in the healthcare system: medication, physician visits, psychotherapy sessions, hospitalization, and so on. Indirect costs refer to the “invisible costs” associated with income losses due to mortality, disability, and care seeking, including lost production due to work absence or early retirement 6, 7. Two kinds of data are needed to calculate the direct and indirect cost of a disorder: epidemiological data on the prevalence of the disorder, healthcare seeking, associated mortality, disability, and in some cases imprisonment; and the per patient costs of the disorder (economic data). The epidemiological data typically are based on representative samples that report prevalence estimates in a defined population, and cohort studies, which link the outcomes described above. Cost data are usually derived from routine statistics such as the average cost of a hospital bed per night for acute or psychiatric hospitals, which are then multiplied with the corresponding epidemiological data.

… the treatment gap for mental and substance use disorders is higher than for any other health sector

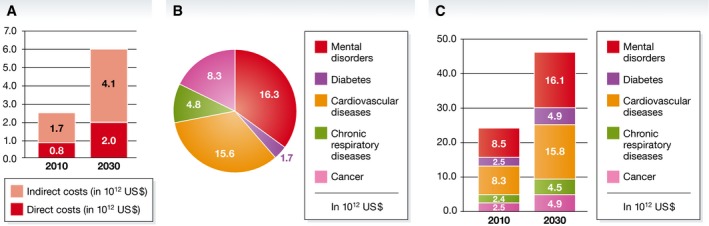

Based on data from 2010, the global direct and indirect economic costs of mental disorders were estimated at US$2.5 trillion. Importantly, the indirect costs (US$1.7 trillion) are much higher than the direct costs (US$0.8 trillion), which contrasts with other key disease groups, such as cardiovascular diseases and cancer. For the EU, a region with highly developed healthcare systems, the direct and indirect costs were estimated at €798 billion 7. Both direct and indirect costs of mental disorders are expected to double by 2030 (Fig 2A). It should be noted that these calculations did not include costs associated with mental disorders from outside the healthcare system, such as legal costs caused by illicit drug abuse.

Figure 2. Economic costs of mental disorders in trillion US$ using three different approaches: direct and indirect costs (A), impact on economic growth (B), and value of statistical life (C).

Based on data from 6.

Lost economic growth

From a macroeconomic perspective, the cost of mental disorders in a defined population can be quantified as lost economic output by estimating the projected impact of mental disorders on the gross domestic product (GDP) (see Sidebar A). The major idea behind this approach is that economic growth depends on labor and capital, both of which can be negatively influenced by disease. Capital is depleted by healthcare expenditures, and labor is depleted by disability and mortality 6. Capital depletion is calculated from information on saving rates, costs of treatment, and the proportion of treatment costs that are funded from savings. Impact on labor is estimated by comparing the GDP to a counterfactual scenario that assumes no deaths from a disease against the projected deaths caused by the respective disease. Such estimates of lost economic output are mostly calculated for somatic diseases, and rarely for mental disorders. However, the impact of mental disorders on economic growth can be estimated only indirectly 6: The lost economic output is first calculated with somatic diseases related to their associated number of disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs). In a second step, the lost economic output for mental disorders is projected using the relative size of the corresponding DALYs for other diseases 6.

Between 2011 and 2030, the cumulative economic output loss associated with mental disorders is thereby projected to US$ 16.3 trillion worldwide, making the economic output loss related to mental disorders comparable to that of cardiovascular diseases, and higher than that of cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes (Fig 2B).

Value of statistical life

The broadest approach used for calculating the economic impact of mental disorders is the value of statistical life (VSL) method (see Sidebar A). This method assumes that tradeoffs between risks and money can be used to quantify the risk of disability or death associated with mental disorders. This quantification analyzes observed tradeoffs or hypothetical preferences, such as data acquired from surveys that ask people how much they would be willing to pay to avoid a particular risk, or how much money they would need to take on that risk 6. The VSL is then calculated from these subjective risk‐value ratios. For example, suppose that the average lifetime risk of dying from a depressive disorder is 15 in 1,000. Suppose further that there are measures that could reduce that risk to 5 in 1,000. If people of a certain population are willing to spend on average US$50,000 for these measures, VLS in that population would be US$5 million ($50,000/[(15–5)/1,000]). The same logic can also be applied when evaluating the willingness to monetarily pay in order to avoid living with a certain disease. As a result, the VSL approach not only accounts for lost income and out‐of‐pocket spending on information, medications, and care, but also for costs that people associate with disability and suffering.

Using the VSL approach, the global economic burden of mental disorders was estimated at US$8.5 trillion in 2010. Similar to the impact on economic growth, this estimate is comparable to that of cardiovascular diseases and higher than that of cancer, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes. This economic burden is also expected to almost double until 2030 (Fig 2C).

In summary, mental disorders cause tremendous economic costs, directly via relatively low costs in the healthcare system, and indirectly via proportionally high productivity losses and impact on economic growth. This pattern of relatively low direct versus comparatively high indirect costs is different from almost all other disease groups even though the full range of mental disorders has barely been taken into account. Although the estimated size of economic costs depends on the analytic approach, the available data from 2010 show that the costs of mental disorders can be estimated at US$2.5 trillion using a traditional human capital approach, or US$8.5 trillion using a willingness to pay approach (the global health spending in 2009 was approx. US$5 trillion 6). Mental disorders therefore account for more economic costs than chronic somatic diseases such as cancer or diabetes, and their costs are expected to increase exponentially over the next 15 years.

Lack of action

The above summary on the global economic costs of mental disorders is corroborated by numerous national studies and an EU‐wide study by the European Brain Council 7. How were these studies received and did policy change the level of funding for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment? In the EU and globally, we do not see much of a response. Mental and substance use disorders are often not part of current health coverage schemes 8: Even though some of these schemes are labeled as “universal health care”, they exclude mental and/or substance use disorders. This situation persists even though the respective healthcare interventions on the population level, for instance, the availability of alcohol; the community level, such as life skills training in schools; and the healthcare level, are effective and can be appropriately implemented (see Sidebar A). Moreover, their implementation is often cost‐effective: The benefit‐to‐cost ratio of investments to increase treatment rates for common mental disorders is between 2.3 and 5.7 to 1 (see Sidebar A). However, the treatment gap for mental and substance use disorders is higher than for any other health sector. Access to mental health care is generally restricted owing to a lack of personnel and infrastructure, and effective evidence‐based treatments are not provided. Importantly, specific prevention is almost completely lacking, with many high‐income countries being no exception (see Sidebar A).

What are the reasons for these remarkable deficits and this evident lack of political commitment to address the problem? First, we have to acknowledge that the development and implementation of sound and effective diagnostic and treatment measures for mental health is still in its relative infancy; many evidence‐based treatments and interventions have only become available during the past 30 years. Thus, capacity building in terms of personnel, infrastructure, and other resources is still far behind other disease areas.

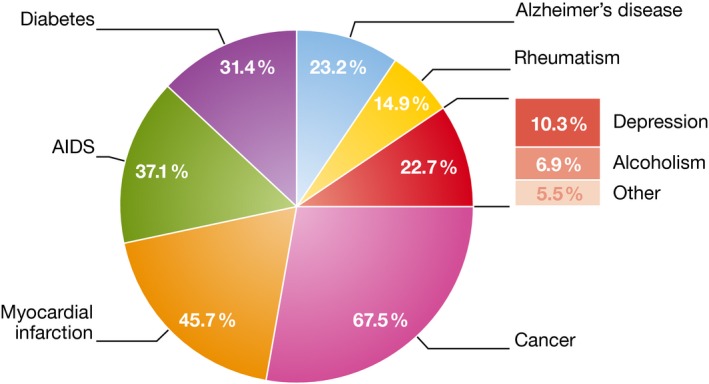

Beyond this, we speculate that stigmatization and misconceptions of both mental and addictive disorders seem to play a major role. It is not only lay people who seem to believe that mental and substance use disorders are not “real diseases”, that they cannot be treated effectively, and that people affected are at least partly responsible (see Sidebar A). As a consequence, societies are willing to spend much more on somatic diseases than on mental disorders, even though both disability and economic costs are at least as high as those caused by somatic conditions. An impressive example that illustrates the current public opinion about the allocation of resources is a study by Schomerus et al 9. Using a sample from Germany's general population, adults were asked to name three out of nine medical conditions for which they would prefer resources not to be cut should general cutbacks within the healthcare budget become necessary (Fig 3). About two‐thirds of respondents named cancer as the medical condition that should be spared from cutbacks, followed by myocardial infarction, AIDS, and diabetes. Only a small minority of respondents named mental disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia.

Figure 3. Medical conditions for which resources should not be cut in case of general cutbacks within the healthcare budget (in %, multiple answers were possible).

Based on data from 9.

… societies are willing to spend much more on somatic diseases than on mental disorders, even though both disability and economic costs are at least as high as those caused by somatic conditions

Beyond the effects of public opinion, funding decisions in many societies are still based on mortality and life expectancy, and while mental disorders indirectly contribute to a high level of mortality (see Sidebar A), they rarely appear on death certificates. Finally, it does not seem to be well known that mental disorders disproportionally contribute to the so‐called high‐cost users in our healthcare system (see Sidebar A).

The need for change

For these reasons, without reconsideration of the cost of mental disorders, the cost benefits of treatment and preventive interventions, and the need for a comprehensive change in stigmatization, the current underfunding of mental health care is likely to persist. Although examples of large‐scale initiatives to improve this situation have started emerging 10, there is still a very long way to go. Society, politicians, and stakeholders have to be consistently and persistently informed about the true burden of mental disorders, including the individual burden and the full range of potential economic costs, but also about the effectiveness, the feasibility, and affordability of measures to reduce that burden. If we continue to take these actions, society will hopefully be more willing to come to accept that spending money for preventing and treating mental disorders is a sustainable investment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Sidebar A: Further reading.

Burden of diseases

Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Ozgoren AA, Abd‐Allah F, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abraham JP, Abubakar I, Abu‐Raddad LJ et al (2015) Global, regional, and national disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 386: 2145–2191

Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (2015) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386: 743–800

Direct and indirect costs

Knapp M (2003) Hidden costs of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry 183: 477–478

Impact on economic growth

Abegunde D, Stanciole A (2006) An estimation of the economic impact of chronic noncommunicable diseases in selected countries. Geneva: World Health Organization

The value of statistical life

Johansson PO (2001) Is there a meaningful definition of the value of a statistical life? J Health Econ 20: 131–139

Treatment coverage

Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B (2004) The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ 82: 858–866

Stigmatization

Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Schomerus G (2013) Attitudes towards psychiatric treatment and people with mental illness: changes over two decades. Br J Psychiatry 203: 146–151

High‐cost users

de Oliveira C, Cheng J, Vigod S, Rehm J, Kurdyak P (2016) Patients with high mental health costs incur over 30 percent more costs than other high‐cost patients. Health Aff 35: 36–43

Mortality

Nordentoft M, Wahlbeck K, Hällgren J, Westman J, Osby U, Alinaghizadeh H, Gissler M, Laursen TM (2013) Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PloS One 8: e55176

Effective Interventions

Petersen I, Evans‐Lacko S, Semrau M, Barry M, Chisholm D, Gronholm P, Egbe CO, Thornicroft G (2016) Population and community platform interventions. In Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, Laxminarayan R, Medina‐Mora ME (eds), pp 183‐200. Washington, DC: The World Bank

Shidhaye R, Lund C, Chisholm D (2016) Health care platform interventions. In Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, Laxminarayan R, Medina‐Mora ME (eds), pp 201–218. Washington, DC: The World Bank

Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, Rasmussen B, Smit F, Cuijpers P, Saxena S (2016) Scaling‐up treatment of depression and anxiety: a global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3: 415–424

EU initiatives and recommendations

Wykes T, Haro JM, Belli SR, Obradors‐Tarragó C, Arango C, Ayuso‐Mateos JL, Bitter I, Brunn M, Chevreul K, Demotes‐Mainard J et al (2015) Mental health research priorities for Europe. Lancet Psychiatry 2: 1036–1042

References

- 1. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU (2012) Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 21: 169–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jonsson B, Olesen J, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Faravelli C et al (2011) The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21: 655–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T, Ferrari AJ, Hyman SE, Laxminarayan R, Levin C et al (2016) Global priorities for addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders In Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, Laxminarayan R, Medina‐Mora ME. (eds), pp 1–27. Washington, DC: The World Bank; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N et al (2013) Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 382: 1575–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hu T (2004) An international review of the economic costs of mental illness. World Bank Working Paper 31

- 6. Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané‐Llopis E, Abrahams‐Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, Feigl AB, Gaziano T, Mowafi M, Pandya A et al (2011) The global economic burden of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Economic Forum; [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, Allgulander C, Alonso J, Beghi E, Dodel R, Ekman M, Faravelli C, Fratiglioni L et al (2011) Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 21: 718–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chisholm D, Johansson KA, Reykar N, Megiddo I, Nigam A, Strand KB, Colson A, Fekadu A, Verguet S (2016) Universal health coverage for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: an extended cost‐effectiveness analysis In Mental, neurological, and substance use disorders, Patel V, Chisholm D, Dua T, Laxminarayan R, Medina‐Mora ME. (eds), pp 237–251. Washington, DC: The World Bank; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schomerus G, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC (2006) Alcoholism: illness beliefs and resource allocation preferences of the public. Drug Alcohol Depend 82: 204–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haro JM, Luis Ayuso‐Mateos J, Bitter I, Demotes‐Mainard J, Leboyer M, Lewis SW, Linszen D, Maj M, Mcdaid D, Meyer‐Lindenberg A et al (2014) ROAMER: roadmap for mental health research in Europe. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 23: 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]