Abstract

One of the causal agents of human sporotrichosis, Sporothrix schenckii, is the type species of the genus Sporothrix. During the course of the last century the asexual morphs of many Ophiostoma spp. have also been treated in Sporothrix. More recently several DNA-based studies have suggested that species of Sporothrix and Ophiostoma converge in what has become known as Ophiostoma s. lat. Were the one fungus one name principles adopted in the Melbourne Code to be applied to Ophiostoma s. lat., Sporothrix would have priority over Ophiostoma, resulting in more than 100 new combinations. The consequence would be name changes for several economically important tree pathogens including O. novo-ulmi. Alternatively, Ophiostoma could be conserved against Sporothrix, but this would necessitate changing the names of the important human pathogens in the group. In this study, we sought to resolve the phylogenetic relationship between Ophiostoma and Sporothrix. DNA sequences were determined for the ribosomal large subunit and internal transcribed spacer regions, as well as the beta-tubulin and calmodulin genes in 65 isolates. The results revealed Sporothrix as a well-supported monophyletic lineage including 51 taxa, distinct from Ophiostoma s. str. To facilitate future studies exploring species level resolution within Sporothrix, we defined six species complexes in the genus. These include the Pathogenic Clade containing the four human pathogens, together with the S. pallida-, S. candida-, S. inflata-, S. gossypina- and S. stenoceras complexes, which include environmental species mostly from soil, hardwoods and Protea infructescences. The description of Sporothrix is emended to include sexual morphs, and 26 new combinations. Two new names are also provided for species previously treated as Ophiostoma.

Key words: Sporothrix schenckii, Sporotrichosis, Taxonomy, Nomenclature, One fungus one name

Taxonomic novelties: New combinations: Sporothrix abietina (Marm. & Butin) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. aurorae (X.D. Zhou & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. bragantina (Pfenning & Oberw.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. candida (Kamgan et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. cantabriensis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. dentifunda (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. epigloea (Guerrero) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. eucalyptigena (Barber & Crous) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. eucastaneae (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. euskadiensis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. fumea (Kamgan et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. fusiformis (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. gemella (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. gossypina (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. lunata (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. narcissi (Limber) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. nebularis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. nigrograna (Masuya) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. palmiculminata (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. phasma (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. polyporicola (Constant. & Ryman) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. prolifera (Kowalski & Butin) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. protea-sedis (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. stenoceras (Robak) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. thermara (J.A. van der Linde et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. zambiensis (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.

New names: S. dombeyi Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.; S. rossii Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf

Introduction

Sporothrix was established more than a century ago when Hektoen & Perkins (1900) presented a detailed case study of an American boy who contracted a fungal infection after wounding his finger with a hammer. They isolated and described the fungus, for which they provided the binomial Sporothrix schenckii. The epithet was derived from the name of B.R. Schenck, who described a similar fungus two years earlier, isolated from the infected wounds on an adult man (Schenck 1898). Schenck (1898) suggested that the fungus might be a species of Sporotrichum. However, Hektoen & Perkins (1900) applied the new genus name, Sporothrix, without providing an explicit generic diagnosis. The genus was thus considered invalid by most subsequent workers who referred to the fungus as Sporotrichum schenckii (De Beurmann & Gougerot 1911 and others). Carmichael (1962) stated that the fungus referred to by the earlier authors as Sporotrichum schenckii, did “not in the least resemble Sporotrichum aureum”, the type species of the genus Sporotrichum, which was later shown to be a basidiomycete (Von Arx, 1971, Stalpers, 1978). He consequently relegated Sporotrichum schenckii back to Sporothrix, and did not consider it necessary to provide a Latin diagnosis for the genus (Carmichael 1962). Nicot & Mariat (1973) eventually validated the name with S. schenckii as type. de Hoog (1974) accepted their validation in his monograph of the genus, although Domsch et al. (1980) regarded the validation unnecessary “in view of the rather exhaustive descriptio generico-specifica” by Hektoen & Perkins (1900) [see Art. 38.5, McNeill et al. (2012)]. Nonetheless, the monograph of de Hoog (1974) provided the first thorough treatment in which 12 Sporothrix spp. were included and illustrated, together with the asexual states of 12 species of Ophiostoma.

The first connection between Sporothrix and Ophiostoma dates back more than a century, to Münch (1907) who treated the mycelial conidial states of some species of Ophiostoma (Ceratostomella at the time) in the genus Sporotrichum. The previous year, Hedgcock (1906) described the synasexual morphs of some Graphium spp. also as Sporotrichum. Apart from Sporotrichum, both Hedgcock (1906) and Münch (1907) applied additional generic names, such as Cephalosporium and Cladosporium, to variations of the mycelial asexual morphs of Ophiostoma. Interestingly, most of the subsequent taxonomic treatments applied either Cephalosporium or Cladosporium when referring to the asexual morphs of Ophiostoma (Lagerberg et al., 1927, Melin and Nannfeldt, 1934, Siemaszko, 1939, Davidson, 1942, Bakshi, 1950, Mathiesen-Käärik, 1953, Hunt, 1956). Some authors applied other generic names to describe asexual morphs of Ophiostoma, such as Cylindrocephalum, Hormodendron (Robak 1932), Hyalodendron (Goidànich, 1935, Georgescu et al., 1948), and Rhinotrichum (Georgescu et al., 1948, Sczerbin-Parfenenko, 1953). Barron (1968) distinguished between Sporothrix and Sporotrichum, and suggested that the so-called Sporotrichum morphs described for some Ceratocystis (actually Ophiostoma) species should be referred to Sporothrix. In the same year, Mariat & De Bievre (1968) suggested that Sporotrichum schenckii was the asexual morph of a species of Ceratocystis (= Ophiostoma), later specified as O. stenoceras (Andrieu et al., 1971, Mariat, 1971).

De Hoog's (1974) monograph, in which he also listed S. schenckii as asexual morph of O. stenoceras, brought much needed order in the taxonomy of Ophiostoma asexual morphs. His circumscription of Sporothrix accommodated the plasticity of these species that had resulted in the above-mentioned confusion. He also appropriately included the asexual human pathogens in the same genus as the wood-staining fungi and bark beetle associates. Based on his work, many later authors treated asexual morphs previously ascribed to all the genera referred to above, in Sporothrix (Samuels and Müller, 1978, Domsch et al., 1980, Upadhyay, 1981, de Hoog, 1993). Several additional asexual species were also described in Sporothrix from a variety of hosts (de Hoog, 1978, de Hoog and Constantinescu, 1981 Moustafa, 1981, de Hoog et al., 1985, Constantinescu & Ryman 1989, and more). By the middle 1980's, evidence that Sporothrix is not a homogenous group, and that some of the species have basidiomycete affiliations, began to appear (Smith and Batenburg-Van der Vegte, 1985, Weijman and de Hoog, 1985, de Hoog, 1993).

One of the earliest applications of DNA sequencing technology to resolve taxonomic questions in the fungal kingdom was published by Berbee & Taylor (1992). They used ribosomal small subunit (SSU) sequences to show that the asexual S. schenckii was phylogenetically related to the sexual genus Ophiostoma, represented in their trees by O. ulmi and O. stenoceras. This was the first study where DNA sequences were used to place an asexual fungus in a sexual genus. The following year, Hausner et al. (1993b) confirmed the separation of Ceratocystis and Ophiostoma based on ribosomal large subunit (LSU) sequences, and subsequently (Hausner et al. 1993a) published the first phylogeny of the genus Ophiostoma, showing that Ophiostoma spp. with Sporothrix asexual morphs do not form a monophyletic group within the Ophiostomatales. Hausner et al. (2000) produced a SSU phylogeny that included seven species in the Ophiostomatales. For the first time, O. piliferum, type species of Ophiostoma, together with S. schenckii, type species of Sporothrix were included together in a single phylogenetic tree. Ophiostoma piliferum grouped with O. ips, and S. schenckii formed a separate clade with O. stenoceras.

In the two decades subsequent to the first DNA-based phylogeny (Berbee & Taylor 1992), increasing numbers of taxa were included in Ophiostoma phylogenies. In these studies, the separation between Ophiostoma s. str. and what became known as the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex, became more apparent (De Beer et al., 2003, Villarreal et al., 2005, Roets et al., 2006, Zipfel et al., 2006, De Meyer et al., 2008, Linnakoski et al., 2010, Kamgan Nkuekam et al., 2012). This was also evident in the most comprehensive phylogenies of the Ophiostomatales to date that included 266 taxa (De Beer & Wingfield 2013). These authors treated the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex, including 26 taxa producing only sporothrix-like asexual states, in Ophiostoma sensu lato. They excluded the complex from Ophiostoma sensu stricto, which contained several other species with sporothrix-like asexual states, often in combination with synnematous, pesotum-like asexual states.

The capacity to link sexual and asexual species and genera based on DNA sequences, as exhibited by the Berbee & Taylor (1992) study, had a major impact on fungal taxonomy and nomenclature. The long-standing debate regarding the impracticality of a dual nomenclature system culminated in the adoption of a single-name nomenclatural system for all fungi in the newly named International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (ICN) at the 2011 International Botanical Congress in Melbourne, Australia. Only one name for a single fungus has been allowed after 1 January 2013 (Hawksworth, 2011, Norvell, 2011). This means that all names for a single taxon now compete equally for priority, irrespective of the morph that they represent (Hawksworth 2011). If these rules were to be applied indiscriminately and with immediate effect, the taxonomic impacts on the Ophiostomatales would be immense (De Beer & Wingfield 2013) and frustrating to practitioners such as plant pathologists and medical mycologists (Wingfield et al. 2012).

Ophiostoma s. lat. as defined by De Beer & Wingfield (2013) included the O. ulmi-, O. pluriannulatum-, O. ips-, and S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complexes, as well as O. piliferum and more than 20 other Ophiostoma spp. The new rules dictate that Sporothrix as the older name would have priority over Ophiostoma (Hektoen and Perkins, 1900, Sydow and Sydow, 1919). The result would be a redefined Sporothrix containing more than 150 species, 112 of which would require new combinations, including well-known tree pathogens such as the Dutch elm disease fungi, O. ulmi and O. novo-ulmi. Alternatively, the ICN makes provision for the conservation of a younger, better known genus name against an older, lesser known name (Article 14, McNeill et al. 2012). If Ophiostoma were to be conserved against Sporothrix, it would have resulted in only 22 new combinations in Ophiostoma, but with changed names for all the major causal agents of the important human and animal disease sporotrichosis: S. schenckii, S. brasiliensis and S. globosa. Based on a lack of DNA sequence data for a number of Sporothrix spp. at the time, and to avoid nomenclatural chaos, De Beer & Wingfield (2013) made several recommendations that ensured nomenclatural stability for the Ophiostomatales, for the interim and before alternative taxonomic solutions could be found. One of these recommendations was to reconsider the generic status of species complexes such as the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex.

During the past decade, sequence data for several gene regions have been employed to delineate closely related species in the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex. A difficulty encountered has been that medical mycologists working with S. schenckii and the other human- and animal-pathogenic species, have used gene regions to distinguish between cryptic species that differ from those used by plant pathologists and generalist mycologists. The latter group have primarily used sequences for the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) (De Beer et al., 2003, Villarreal et al., 2005) or the beta-tubulin (BT) gene (Aghayeva et al., 2004, Aghayeva et al., 2005, Roets et al., 2006, Roets et al., 2008, Roets et al., 2010, Zhou et al., 2006, De Meyer et al., 2008, Kamgan Nkuekam et al., 2008, Kamgan Nkuekam et al., 2012, Linnakoski et al., 2008, Linnakoski et al., 2010, Madrid et al., 2010a). In contrast, medical mycologists have experimented with several gene regions, still including ITS (Gutierrez Galhardo et al., 2008, Zhou et al., 2014) and BT, but also including chitin synthase, calmodulin (CAL) (Marimon et al., 2006, Marimon et al., 2008), and most recently translation elongation factor-1-alpha (TEF1) and translation elongation factor-3 (TEF3) (Zhang et al., 2015, Rodrigues et al., 2016). CAL became the preferred gene region to distinguish among the human pathogenic species of Sporothrix (Marimon et al., 2007, Madrid et al., 2009, Dias et al., 2011, Oliveira et al., 2011, Romeo et al., 2011, Rodrigues et al., 2014b, Rodrigues et al., 2015a, Rodrigues et al., 2015b, Rodrigues et al., 2016). A potential problem that could arise from this history is that environmental isolates included in clinical studies could be incorrectly identified because at present, no CAL sequences are available for many of the non-pathogenic species in S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex which are mostly from wood, soil and Protea infructescences.

The aims of this study were 1) to redefine the genus Sporothrix, 2) to provide new combinations where necessary, 3) to provide sequence data for ex-type isolates of as many species as possible in the emended genus, so that reference sequences will be available for future taxonomic and clinical studies, and 4) to define emerging species complexes within Sporothrix. To address the genus level questions we employed the ribosomal LSU and ITS regions. Species level questions were addressed using the ITS regions, widely accepted as the universal DNA barcode marker for fungi (Schoch et al. 2012), as well as sequences for the more variable protein-coding CAL and BT genes.

Materials & methods

Isolates

Forty three Ophiostoma, two Ceratocystis and one Dolichoascus species, all with sporothrix-like asexual morphs, were considered in our study, together with 27 Sporothrix spp. without known sexual morphs (Table 1). The total number of 73 species were represented by DNA sequences of 83 isolates, as more than one isolate was included for some of the species. Sixty six of the isolates are linked to type specimens, and sequences of 18 isolates generated in previous studies were obtained from GenBank.

Table 1.

Isolates of species with sporothrix-like asexual states included in phylogenetic analyses in this study. Genbank numbers for sequences obtained in the present study are printed in bold type.

| Previous name | New name | CMW1 | CBS2 or other | Type | Isolated from | Country | Collector | GenBank Accession numbers |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSU | ITS | BT | CAL | ||||||||

| Ceratocystis eucastanea | S. eucastanea | 1124 | 424.77 | T | canker on Castanea dentata | North Carolina, USA | RW Davidson | KX590843 | KX590814 | KX590753 | KX590781 |

| C. gossypina var. robusta | S. rossii | 1118 | 116.78 | T | Dendroctonus adjunctus gallery on P. ponderosa | New Mexico, USA | RW Davidson | KX590844 | KX590815 | KX590754 | JQ511972 |

| Dolichoascus schenckii | syn. S. schenckii | 938.72 | T | Human | France | F Mariat | NA | KP017094 | NA | AM490340 | |

| O. abietinum | S. abietina | 22310 | 125.89 | T | Pseudohylesinus gallery on Abies vejari | Mexico | JG Marmolejo | KX590845 | AF484453 | KX590755 | JQ511966 |

| O. africanum | S. africana | 823 | 116571 | Protea gaguedi | South Africa | MJ Wingfield | DQ316147 | DQ316199 | DQ296073 | NA | |

| O. albidum | syn. S. stenoceras | 1123 | 798.73 | T | Pissodes pini gallery on Pinus sylvestris | Sweden | A Mathiesen-Käärik | KX590846 | AF484475 | KX590756 | KX590782 |

| O. angusticollis | O. angusticollis | 152 | 186.86 | Pinus banksiana | Wisconsin, USA | MJ Wingfield | KX590847 | AY924383* | KX590757* | NA | |

| O. aurorae | S. aurorae | 19362 | 118837 | T | Hylastes angustatus on Pinus elliottii | South Africa | XD Zhou | KX590848 | DQ396796 | DQ396800 | KX590783 |

| O. bragantinum | S. bragantina | 17149 | 474.91 | T | Virgin forest soil | Brazil | W Gams | KX590849 | FN546965 | FN547387 | KX590784 |

| O. candidum | S. candida | 26484 | 129713 | T | Eucalyptus cloeziana | South Africa | G Kamgan Nkuekam | KX590850 | HM051409 | HM041874 | KX590785 |

| O. cantabriense | S. cantabriensis | 39766 | 136529 | T | Hylastes attenuates on Pinus sylvestris | Spain | P Romon | NA | KF951554 | KF951544 | KF951540 |

| O. coronatum | O. coronatum | 37433 | 497.77 | Canada | RW Davidson | KX590851 | AY924385* | KX590758* | KX590786* | ||

| O. denticulatum | O. denticulatum | 1128 | ATCC38087 | T | Ambrosia gallery Pinus ponderosa | Colorado, USA | RW Davidson | KX590852 | KX590816* | KX590759* | NA |

| O. dentifundum | S. dentifunda | 13016 | 115790 | T | Quercus wood | Hungary | C Delatour | KX590853 | AY495434 | AY495445 | KX590787 |

| O. epigloeum | S. epigloea | 22308 | 573.63 | T | Tremella fusiformis | Argentina | RT Guerrero | KX590854 | KX590817 | KX590760 | NA |

| O. eucalyptigena | S. eucalyptigena | 139899 | T | Eucalyptus marginata | Australia | PA Barber | KR476756 | KR476721 | NA | NA | |

| O. euskadiense | S. euskadiensis | 27318 | 122138 | T | Hylurgops palliatus on Pinus radiata | Spain | XD Zhou | NA | DQ674369 | EF396344 | JQ438830 |

| O. fumeum | S. fumea | 26813 | 129712 | T | Eucalyptus cloeziana | South Africa | G Kamgan Nkuekam, J Roux | NA | HM051412 | HM041878 | KX590788 |

| 26820 | Eucalyptus sp. | Zambia | G Kamgan Nkuekam | KX590855 | KX590818 | NA | NA | ||||

| O. fusiforme | S. fusiformis | 9968 | 112912 | T | Populus nigra | Azerbaijan | D Aghayeva | DQ294354 | AY280481 | AY280461 | JQ511967 |

| O. gemellus | S. gemella | 23057 | 121959 | T | Tarsonemus sp. from Protea caffra | South Africa | F Roets | DQ821531 | DQ821560 | DQ821554 | NA |

| O. gossypinum | S. gossypina | 1116 | ATCC18999 | T | P. ponderosa | New Mexico, USA | RW Davidson | KX590856 | KX590819 | KX590761 | KX590789 |

| O. grande | O. grande | 22307 | 350.78 | T | Diatrype fruiting body on bark | Brazil | RD Dumont | KX590857 | NA | NA | KX590790 |

| O. grandicarpum | O. grandicarpum | 1600 | 250.88 | T | Quercus robur | Poland | T Kowalski | KX590858 | KX590820* | KX590762* | NA |

| O. lunatum | S. lunata | 10563 | 112927 | T | Carpinus betulus | Austria | T Kirisits | KX590859 | AY280485 | AY280466 | JQ511970 |

| O. macrosporum | O. macrosporum | 14176 | 367.53 | Ips acuminatus | Sweden | H Francke-Grosmann | EU177468 | KX590821* | KX590763* | NA | |

| O. microsporum | O. microsporum | 17152 | 440.69 | NT | Quercus sp. | Virginia, USA | EG Kuhlman | KX590860 | KX590822* | KX590764* | NA |

| O. narcissi | S. narcissi | 22311 | 138.50 | T | Narcissus sp. | Netherlands | DP Limber | KX590861 | AF194510 | KX590765 | KX590791 |

| O. nebulare | S. nebularis | 22797 | Orthotomicus erosus on Pinus radiata | Spain | P Romon | KX590862 | KX590823 | NA | JQ438829 | ||

| 27319 | 122135 | T | Hylastes attenuatus on Pinus radiata | Spain | P Romon | NA | KX590824 | KX590766 | JQ438828 | ||

| O. nigricarpum | O. nigricarpum | 651 | 638.66 | P | Pseudotsuga menziesii | Idaho, USA | RW Davidson | DQ294356 | AY280490* | AY280480* | NA |

| O. nigricarpum | O. nigricarpum | 650 | 637.66 | T | Abies sp. | Idaho, USA | RW Davidson | NA | AY280489* | AY280479* | NA |

| O. nigrogranum | S. nigrograna | 14487 | MAFF410943 | T | Pinus densiflora | Japan | H Masuya | KX590863 | KX590825 | NA | NA |

| O. noisomeae | O. noisomeae | 40326 | 141065 | T | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | KX590864 | KU639631 | KU639628 | KX590792 |

| 40329 | 141066 | P | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | NA | KU639634 | KU639630 | KU639611 | ||

| O. nothofagi | S. dombeyi | 1023 | 455.83 | T | Nothofagus dombeyi | Chile | H Butin | KX590865 | KX590826 | KX590767 | KX590793 |

| O. palmiculminatum | S. palmiculminata | 20677 | 119590 | T | Protea repens | South Africa | F Roets | DQ316143 | DQ316191 | DQ316153 | KX590794 |

| O. phasma | S. phasma | 20676 | 119721 | T | Protea laurifolia | South Africa | F Roets | DQ316151 | DQ316219 | DQ316181 | KX590795 |

| O. polyporicola | S. polyporicola | 5461 | 669.88 | T | Fomitopsis pinicola | Sweden | S Ryman | KX590866 | KX590827 | KX590768 | KX590796 |

| O. ponderosae | O. ponderosae | 37953 | ATCC26665 | T | P. ponderosa | Arizona, USA | TE Hinds | KX590867 | NA | NA | NA |

| O. ponderosae | ‘O. ponderosae 2’ | 128 | RWD899 | Not known | USA | TE Hinds | KX590868 | KX590828* | KX590769* | NA | |

| O. proliferum | S. prolifera | 37435 | 251.88 | T | Quercus robur | Poland | T Kowalski | KX590869 | KX590829 | KX590770 | KX590797 |

| O. protearum | S. protearum | 1107 | 116654 | P. caffra | South Africa | MJ Wingfield | DQ316145 | DQ316201 | DQ316163 | KX590798 | |

| O. protea-sedis | S. protea-sedis | 28601 | 124910 | T | P. caffra | Zambia | F Roets | KX590870 | EU660449 | EU660464 | NA |

| O. rostrocoronatum | O. rostrocoronatum | 456 | 434.77 | Pulpwood chips of hardwoods | Colorado, USA | RW Davidson | KX590871 | AY194509* | KX590771* | NA | |

| O. splendens | S. splendens | 897 | 116379 | Protea repens | South Africa | F Roets | AF221013 | DQ316205 | DQ316169 | KX590799 | |

| O. stenoceras | S. stenoceras | 3202 | 237.32 | T | Pine pulp | Norway | H Robak | DQ294350 | AY484462 | DQ296074 | JQ511956 |

| O. tenellum | O. tenellum | 37439 | 189.86 | Pinus banksiana | Wisconsin, USA | MJ Wingfield | KX590872 | AY934523* | KX590772* | KX590800* | |

| O. thermarum | S. thermara | 38930 | 139747 | T | Cyrtogenius africus galleries on Euphorbia ingens | South Africa | JA van der Linde | KR051127 | KR051115 | KR051103 | NA |

| O. valdivianum | O. valdivianum | 449 | 454.83 | T | Nothofagus alpina | Chile | H Butin, M Osorio | KX590873 | KX590830 | KX590773 | KX590801 |

| O. zambiensis | S. zambiensis | 28604 | 124912 | T | Protea caffra | Zambia | F Roets | KX590874 | EU660453 | EU660473 | NA |

| Sporotrichum tropicale nom. inval. | syn. S. globosa | 17204 | 292.55 | T | Human | India | LM Gosh | KX590875 | KP017086 | KX590774 | AM490354 |

| Sporothrix aemulophila | S. aemulophila | 40381 | 140087 | T | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | NA | KT192603 | KT192607 | KX590802 |

| S. albicans | syn. S. pallida | 17203 | 302.73 | T | Soil | England | SB Saksena | KX590876 | KX590831 | AM498343 | AM398396 |

| S. brasiliensis | S. brasiliensis | 29127 | 120339 | T | Human skin | Brazil | M dos Santos Lazéra | KX590877 | KX590832 | AM116946 | AM116899 |

| S. brunneoviolacea | S. brunneoviolacea | 37443 | 124561 | T | Soil | Spain | H Madrid | KX590878 | FN546959 | FN547385 | KX590803 |

| S. cabralii | S. cabralii | 38098 | CIEFAP456 | T | Nothofagus pumilio | Argentina | A de Errasti | KT362229 | KT362256 | KT381295 | KX590804 |

| S. catenata | Trichomonascus ciferrii | 17161 | 215.79 | T | Calf skin | Romania | O Constantinescu | KX590879* | KX590833* | NA | NA |

| S. catenata | S. pallida | 17162 | 461.81 | Nail of man | Netherlands | GS de Hoog | NA | KX590834 | KX590775 | KX590805 | |

| S. chilensis | S. chilensis | 139891 | T | Human | Chile | R Cruz Choappa | NA | KP711811 | KP711813 | KP711815 | |

| S. curviconia | S. curviconia | 17164 | 959.73 | T | Terminalia ivorensis | Ivory Coast | J Devois | KX590880 | KX590835 | KX590776 | NA |

| S. curviconia | ‘S. curviconia 2’ | 17163 | 541.84 | Pinus radiata log | Chile | HL Peredo | KX590881 | KX590836 | KX590777 | JQ511968 | |

| S. dimorphospora | S. dimorphospora | 12529 | 553.74 | T | Soil | Canada | RAA Morall | NA | AY495428 | AY495439 | NA |

| 37446 | 125442 | Soil | Spain | C Silverra | KX590882 | FN546961 | FN547379 | KX590806 | |||

| S. fungorum | Uncertain | 17165 | 259.70 | T | Fomes fomentarius basidiome | Germany | W Gams | KX590883* | KX590837* | NA | NA |

| S. globosa | S. globosa | 29128 | 120340 | T | Human face | Spain | C Rubio | KX590884 | KX590838 | AM116966 | AM166908 |

| S. guttuliformis | S. guttuliformis | 17167 | 437.76 | T | Soil | Malaysia | T Furukawa | KX590885 | KX590839 | KX590778 | KX590807 |

| S. humicola | S. humicola | 7618 | 118129 | T | Soil | South Africa | HF Vismer | EF139114 | AF484472 | EF139100 | KX590808 |

| S. inflata | ‘S. inflata 2’ | 12526 | 156.72 | Greenhouse soil | Netherlands | H Kaastra-Howeler | NA | AY495425 | AY495436 | NA | |

| S. inflata | S. inflata | 12527 | 239.68 | T | Wheat field soil | Germany | W Gams | DQ294351 | AY495426 | AY495437 | NA |

| S. itsvo | S. itsvo | 40370 | 141063 | T | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | NA | KX590840 | KU639625 | NA |

| S. lignivora | Hawksworthiomyces lignivora | 18600 | 119148 | T | Eucalyptus utility poles | South Africa | EM de Meyer | EF139119 | EF127890* | EF139104* | NA |

| 18599 | 119147 | Eucalyptus utility poles | South Africa | EM de Meyer | KX396545 | EF127889* | EF139103* | NA | |||

| S. luriei | S. luriei | 17210 | 937.72 | T | Human skin | South Africa | H Lurie | KX590886 | AB128012 | AM747289 | AM747302 |

| S. mexicana | S. mexicana | 29129 | 120341 | T | Soil, rose tree | Mexico | A Espinosa | KX590887 | KX590841 | AM498344 | AM398393 |

| S. nivea | syn. S. pallida | 17168 | 150.87 | T | Sediment in water purification plant | Germany | G Teuscher, F Schauer | KX590888 | EF127879 | KX590779 | KX590809 |

| S. nothofagi | S. nothofagi | 37658 | NZFS519 | T | Nothofagus fusca | New Zealand | W Faulds | KX590889 | NA | KX590780* | KX590810* |

| S. pallida | S. pallida | 17209 | 131.56 | T | Stemonitis fusca | Japan | K Tubaki | EF139121 | EF127880 | EF139110 | KX590811 |

| S. rapaneae | S. rapaneae | 40369 | 141060 | T | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | NA | KU595583 | KU639624 | KU639609 |

| S. schenckii | S. schenckii | 29351 | 359.36 | T | Human | USA | CF Perkins | KX590890 | KX590842 | AM116911 | AM117437 |

| S. stylites | S. stylites | 14543 | 118848 | T | Pine utility poles | South Africa | EM de Meyer | EF139115 | EF127883 | EF139096 | KX590812 |

| S. uta | S. uta | 40316 | 141069 | P | Rapanea melanophloeos | South Africa | T Musvuugwa | NA | KU595577 | KU639616 | KU639605 |

| S. variecibatus | S. variecibatus | 23051 | 121961 | T | Trichouropoda sp. from Protea repens | South Africa | F Roets | DQ821537 | DQ821568 | DQ821539 | KX590813 |

T = ex-type; NT = ex-neotype; P = ex-paratype.

*Sequences not included in ITS, BT and CAL analyses of the present study because sequences were too divergent.

CMW = Culture Collection of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, South Africa.

CBS = Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; ATCC = American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA; MAFF = Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Genetic Resource Centre, Culture Collection of National Institute of Agrobiological Resources, Japan; RWD = Private collection of R.W. Davidson; CIEFAP = Culture collection of the Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico, Argentina; NZFS = New Zealand Forest Research Culture Collection, Rotorua, New Zealand.

DNA extraction, PCR and DNA sequencing

DNA was extracted following the technique described by Duong et al. (2012). The ribosomal LSU region was amplified and sequenced using primers LR3 and LR5 (White et al. 1990), while ITS1F (Gardes & Bruns 1993) and ITS4 (White et al. 1990) were used for the ITS regions. The PCR reactions of the BT genes were run using primers T10 (O'Donnell & Cigelnik 1997) and Bt2b, while Bt2a and Bt2b (Glass & Donaldson 1995) were used for sequencing reactions. For the CAL gene, primers CL1 and CL2a (O'Donnell et al. 2000) were used for most species, but a new primer pair was designed for some Ophiostoma spp. that could not be amplified with these primers. The new primers were CL3F (5′-CCGARTWCAAGGAGGCSTTC-3′) and CL3R (5′-TTCTGCATCATRAGYTGSAC-3′). PCR and sequencing protocols were as described by Duong et al. (2012), other than the annealing temperature being optimized for some individual reactions.

Phylogenetic analyses

Data sets of sequences derived in the present study (Table 1) together with reference sequences obtained from NCBI GenBank, were compiled using MEGA 6.06 (Tamura et al. 2013). All datasets (LSU, ITS, BT and CAL) were aligned using an online version of MAFFT 7 (Katoh & Standley 2013) and subjected to Gblocks 0.91b (Castresana 2000) using less stringent selection options, to eliminate poorly aligned positions and divergent regions from subsequent phylogenetic analyses. All datasets obtained from Gblocks were subjected to Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) analyses. ML analyses using RaxML (Stamatakis 2006) were conducted with raxmlGUI 1.3 (Silvestro & Michalak 2012) with 10 runs using the GTRGAMMA substitution model and 1 000 bootstraps each. BI analyses were conducted with MrBayes 3.2.5 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) with 10 runs using the GTRGAMMA substitution model, and 5 M generations each with tree sampling every 100th generation. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated for each dataset after discarding 25% of the trees sampled as prior burn-in.

Results

Phylogenetic analyses

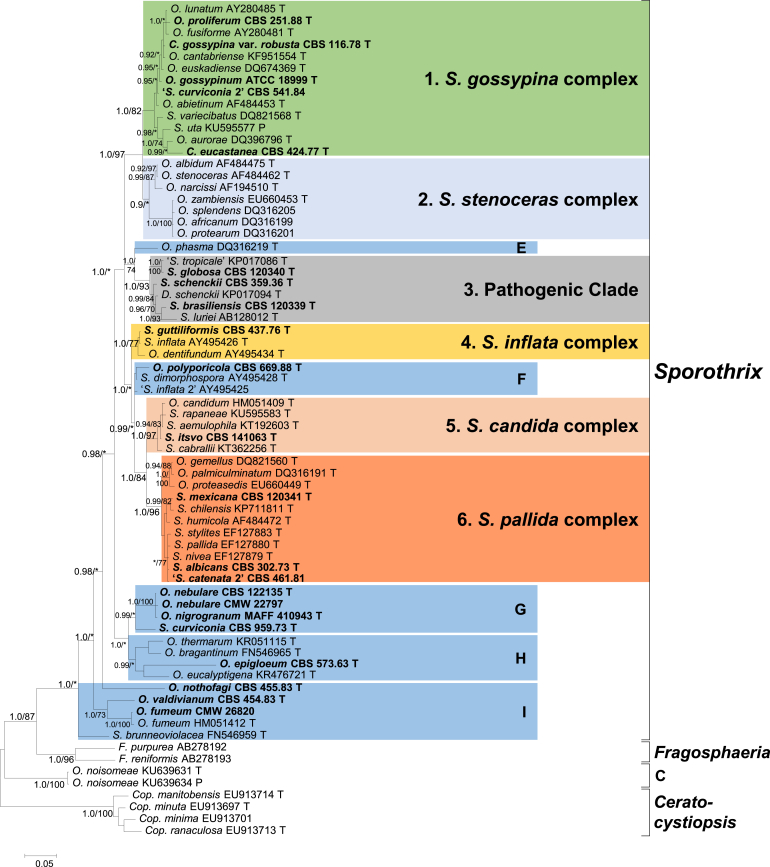

Trees obtained from MrBayes analyses with support values for branches are presented in Fig. 1 (LSU), Fig. 2 (ITS), Fig. 3 (BT) and Fig. 4 (CAL). The numbers of taxa and characters included in the respective data sets, as well as outgroups, are presented in the legends of Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4. Topologies of trees obtained from ML analyses were largely congruent with the MrBayes trees and bootstrap support values for these are also indicated in the figures.

Fig. 1.

Phylogram depicts the taxonomic relationship of Sporothrix, Ophiostoma s. str. and other genera in the Ophiostomatales based on LSU sequences. The tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 using the GTR+G nucleotide substitution model. The aligned dataset included 151 taxa (730 total characters), 696 characters remained after treatment with Gblocks, 237 of which were variable. Bayesian posterior probabilities (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap supports are indicated at nodes as BI/ML. * = no support or bootstrap support values <70% and posterior probabilities <0.90. Sequences for taxa in bold-type were generated in this study. T = ex-holotype; NT = ex-neotype; P = ex-paratype.

Fig. 2.

Bayesian phylogram derived from analyses of the ITS dataset (70 taxa included, 516 characters remained after treatment with Gblocks, 259 of which were variable). The tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 using the GTR+G nucleotide substitution model. Bayesian posterior probabilities (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap supports are indicated at nodes as BI/ML. * = no support or bootstrap support values <70% and posterior probabilities <0.90. Sequences for taxa in bold-type were generated in this study. T = ex-holotype; P = ex-paratype.

Fig. 3.

Bayesian phylogram derived from analyses of the BT dataset (64 taxa included, 245 characters remained after treatment with Gblocks, 85 of which were variable). Presence (intron numbers 3, 4 and 5) or absence (-) of introns are indicated in the column on the right. The tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 using the GTR+G nucleotide substitution model. Bayesian posterior probabilities (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap supports are indicated at nodes as BI/ML. * = no support or bootstrap support values <70% and posterior probabilities <0.90. Sequences for taxa in bold-type were generated in this study. T = ex-holotype; P = ex-paratype.

Fig. 4.

Bayesian phylogram derived from analyses of the CAL dataset (51 taxa included, 530 characters after Gblock, of which 293 were variable character). Presence (intron numbers 3, 4 and 5) or absence (-) of introns are indicated in the column on the right. The tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 using the GTR+G nucleotide substitution model. Bayesian posterior probabilities (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) bootstrap supports are indicated at nodes as BI/ML. * = no support or bootstrap support values <70% and posterior probabilities <0.90. Sequences for taxa in bold-type were generated in this study. T = ex-holotype; P = ex-paratype.

The LSU data (Fig. 1) showed well-supported lineages for the following genera (as defined by De Beer & Wingfield 2013) in the Ophiostomatales: Leptographium s. lat., Ophiostoma s. str., Fragosphaeria, Ceratocystiopsis, Raffaelea s. str., and Graphilbum. Two genera described subsequent to the study of De Beer & Wingfield (2013) were also supported in the LSU analyses, namely Aureovirgo (Van der Linde et al. 2016) and Hawksworthiomyces (De Beer et al. 2016). The S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex as defined by De Beer & Wingfield (2013), formed a well-supported lineage distinct from Ophiostoma s. str. This lineage included Sporothrix schenckii, the type species of Sporothrix, and was thus labelled as Sporothrix. It also included 16 other known Sporothrix spp., 29 known Ophiostoma spp., the ex-type isolates of Ceratocystis gossypina var. robusta and C. eucastanea, and a novel taxon labelled as ‘S. curviconia 2’, that was previously identified as that species. One Sporothrix species, S. nothofagi, did not group in Sporothrix, but in a distinct lineage within Leptographium s. lat. Several species with sporothrix-like asexual morphs grouped in Ophiostoma s. str. and are listed in the Taxonomy section below. However, some Ophiostoma spp. with sporothrix-like asexual morphs grouped in smaller lineages (labelled A to D, Fig. 1) outside or between the major genera.

For the compilation of the ITS data set, outgroups were selected for Sporothrix based on the LSU trees (Fig. 1). The lineages closest to Sporothrix were chosen and included species of Fragosphaeria, Ceratocystiopsis and Lineage C (Fig. 2). Attempts to include species from more genera such as Ophiostoma s. str. and from lineages A, B and D, resulted in data sets that were too variable to align appropriately, and such taxa were thus excluded from further analyses. The same group of taxa constituting the lineage defined as Sporothrix in the LSU trees (Fig. 1), again formed a well-supported lineage in the trees based on ITS data (Fig. 2). However, the ITS trees provided substantially more resolution than the LSU trees and revealed several lineages within the genus Sporothrix. Well-supported lineages (numbered 1 to 6) that corresponded with those in the BT (Fig. 3) and CAL (Fig. 4) trees, were recognized as species complexes. These complexes were defined following the criteria applied by De Beer & Wingfield (2013) in recognising the 18 species complexes they defined in the Ophiostomatales. Each complex was named based on the species that was first described in that complex (Fig. 2). The only exception was Lineage 3 that contained S. schenckii and the other human pathogens. Chen et al. (2016) argued against the use of the term “complex” in medical mycology for a clade such as this that includes well-defined species causing different disease symptoms, and that differ from each other in routes of transmission, virulence and antifungal susceptibility. In line with other recent publications dealing with S. schenckii and the other pathogenic species (Rodrigues et al., 2015a, Rodrigues et al., 2015b, Zhang et al., 2015), we thus refer to Lineage 3 as the Pathogenic Clade. A few species did not form part of consistently supported lineages and were labelled as groups E to I to facilitate discussion.

Species of Ceratocystiopsis and Lineage C were used as outgroups in the BT data set because no BT sequences were available for Fragosphaeria. Apart from species complex 1, all four the other complexes defined based on ITS (Fig. 2), also had strong statistical support in the BT trees (Fig. 3). The BT sequences obtained mostly spanned exons 3, 4, 5, and the 5′ part of exon 6, but the BT genes of different species had a variety of intron arrangements (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Most species lacked one to two of the introns, and the arrangements corresponded with the species complexes. Species complexes 1 and 2, and group E lacked both introns 3 and 4 and only contained intron 5 (-/-/5). Taxa in complexes 3, 4, 5 and 6, and groups F, G, H and I, all contained introns 3 and 5 but lacked intron 4 (3/-/5). The only exception was O. nothofagi that contained intron 4, but lacked intron 5 (?/4/-). The fragment of the latter species was too short to determine whether intron 3 was present or not. As more than 50% of basepairs from mostly introns were excluded from the analyses by Gblocks (see legend of Fig. 3), the trees obtained did not fully reflect differences in BT sequences between closely related taxa.

Table 2.

A comparative summary of morphological, ecological, and genetic characters of species of Sporothrix, as well Ophiostoma spp. with sporothrix-like asexual states of uncertain generic placement.

In the analyses of the CAL gene region (Fig. 4), only Lineage C was included as outgroup because CAL sequences were not available for Fragosphaeria and Ceratocystiopsis. The topology of the trees generally reflected those of the ITS and BT trees, and all six species complexes were statistically supported. The intron arrangements for the CAL gene region were less variable than those of BT, with only two patterns observed (Table 2 and Fig. 3). All taxa in Sporothrix for which CAL data were available had a pattern of 3/4/-, with the only exceptions found in O. nothofagi and S. brunneoviolacea (in Group I), which had all three introns (3/4/5). Similar to those for BT, the CAL trees did not fully reflect sequence differences between closely related taxa because a considerable portion of the more informative intron data had been excluded from the analyses.

Taxonomy and nomenclator

Based on phylogenetic analyses of four gene regions (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) we conclude that the previously recognised S. schenckii–O. stenoceras species complex in Ophiostoma s. lat., represents a distinct genus in the Ophiostomatales. This genus is Sporothrix, with S. schenckii as type species, and it is distinct from Ophiostoma s. str., defined by O. piliferum as type species. Based on one fungus one name principles, we redefine Sporothrix, which previously included only asexual morphs (de Hoog 1974), such that the generic diagnosis now also reflects the morphology of species with known sexual morphs.

Sporothrix Hektoen & C.F. Perkins, J. Exp. Med. 5: 80. 1900. emend. Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf.

Synonyms: Sporotrichopsis Gueguen. In De Beurmann & Gougerot, Archs Parasit. 15: 104. 1911. [type species S. beurmannii; nom. inval., Art. 38.1]

Dolichoascus Thibaut & Ansel. In Ansel & Thibaut, Compt. Rend. Hebd. Séances Acad. Sci. 270: 2173. 1970. [type species D. schenckii; nom. inval., Art. 40.1]

Sporothrix section Sporothrix Weijman & de Hoog, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 51: 118. 1985.

Ascocarps dark brown to black, bases globose; necks straight or flexuous, cylindrical, tapering slightly to apex, up to 1 600 μm long, brown to black; ostiole often surrounded by divergent, ostiolar hyphae, sometimes absent. Asci 8-spored, evanescent, globose to broadly clavate. Ascospores hyaline, aseptate, lunate, allantoid, reniform, orange section-shaped, sheath absent. Asexual states micronematous, mycelial, hyaline or occasionally pigmented conidia produced holoblastically on denticulate conidiogenous cells. Phylogenetically classified in the Ophiostomatales.

Type species: Sporothrix schenckii Hektoen & C.F. Perkins

Note: The synonymies of Sporotrichopsis and Dolichoascus with Sporothrix are discussed in the Notes accompanying S. schenckii below.

-

1.

Sporothrix abietina (Marm. & Butin) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817561.

Basionym: Ophiostoma abietinum Marm. & Butin, Sydowia 42: 194. 1990.

Notes: De Beer et al. (2003) incorrectly treated several isolates of S. abietina, including the ex-type, as O. nigrocarpum (now O. nigricarpum). Aghayeva et al. (2004) showed that these two species are distinct, and that De Beer's isolates all grouped with the ex-type isolate of S. abietina, that also represented the species in our analyses and formed part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). This species should not be confused with Leptographium abietinum (Peck) M.J. Wingf. that resides in the Grosmannia penicillata complex (De Beer and Wingfield, 2013, De Beer et al., 2013).

-

2.

Sporothrix aemulophila T. Musvuugwa et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 108: 945. 2015.

Note: Forms part of the S. candida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

3.

Sporothrix africana G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 105: 242. 2001. [as ‘africanum’]

Synonym: Ophiostoma africanum G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res.105: 241. 2001.

Note: Forms part of the S. stenoceras complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

4.

Sporothrix aurorae (X.D. Zhou & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817562.

Basionym: Ophiostoma aurorae X.D. Zhou & M.J. Wingf., Stud. Mycol. 55: 275. 2006.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

5.

Sporothrix bragantina (Pfenning & Oberw.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817564.

Basionym: Ophiostoma bragantinum Pfenning & Oberw., Mycotaxon 46: 381. 1993.

Note: Forms part of Lineage H (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

6.

Sporothrix brasiliensis Marimon et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 45: 3203. 2007.

Note: Forms part of the Pathogenic Clade (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

7.

Sporothrix brunneoviolacea Madrid et al., Mycologia 102: 1199. 2010.

Notes: Madrid et al. (2010a) described some isolates previously referred to as S. inflata by Halmschlager & Kowalski (2003) and Aghayeva et al. (2005), as S. brunneoviolacea. In all four of our phylogenies, this species grouped peripheral to the core species complexes in Sporothrix (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4), in an unsupported group (Group I, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Although it differs from most Sporothrix spp. in its CAL intron arrangement (Table 2), it is retained in Sporothrix for the present.

-

8.

Sporothrix cabralii de Errasti & Z.W. de Beer, Mycol. Prog. 15(17): 10. 2016.

Note: Forms part of the S. candida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

9.

Sporothrix candida (Kamgan et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817565.

Basionym: Ophiostoma candidum Kamgan et al., Mycol. Progress 11: 526. 2012.

Note: The first taxon to be described in this newly defined complex and thus the name-bearing species of the S. candida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

10.

Sporothrix cantabriensis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817566.

Basionym: Ophiostoma cantabriense P. Romón et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 106: 1175. 2014.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

11.

Sporothrix chilensis A.M. Rodrigues et al., Fung. Biol. 120: 256. 2016.

Note: Forms part of the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

12.

Sporothrix curviconia de Hoog, Stud. Mycol. 7: 33. 1974.

Notes: The ex-type isolate (CBS 959.73) from Terminalia in the Ivory Coast forms part of group G (Fig. 2, Fig. 3) and its placement in Sporothrix is confirmed. Sequences of another isolate (CBS 541.84) previously treated as S. curviconia from Pinus radiata in Chile are labelled in our trees as ‘S. curviconia 2’. This isolate grouped close to O. abietinum and related species in the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) and most likely represents a novel taxon.

-

13.

Sporothrix dentifunda (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817567.

Basionym: Ophiostoma dentifundum Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 109: 1134. 2005.

Note: Forms part of the S. inflata complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

14.

Sporothrix dimorphospora (Roxon & S.C. Jong) Madrid et al., Mycologia 102: 1199. 2010.

Basionym: Humicola dimorphospora Roxon & S.C. Jong, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 517. 1974.

Note: Forms part of Clade F (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

15.

Sporothrix dombeyi Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., nom. nov. MycoBank MB817568.

Synonyms: Ceratocystis nothofagi Butin. In Butin & Aquilar, Phytopathol. Z. 109: 84. 1984.

Ophiostoma nothofagi (Butin) Rulamort, Bull. Soc. Bot. Centre-Ouest, n.s. 17: 192. 1986.

Notes: Based on cultural morphology and in the absence of DNA sequence data, De Beer et al. (2013) suggested that O. nothofagi might be related to species such as O. piliferum or O. pluriannulatum rather than to the S. schenckii-O. stenoceras complex. However, our sequences of the ex-type isolate confirms its placement in Sporothrix (Group I, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). It thus needed to be transferred to Sporothrix. However, since the epithet nothofagi is unavailable in Sporothrix because of Sporothrix nothofagi Gadgil & M.A. Dick [Art. 6.11], we provided a new name based on the epithet of its original host tree (Nothofagus dombeyi), rather than the genus of the host. Sporothrix nothofagi Gadgil & M.A. Dick is not closely related to the latter species and is placed in Leptographium s. lat. (see below under species of uncertain generic status in the Ophiostomatales).

-

16.

Sporothrix epigloea (Guerrero) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817569.

Basionym: Ceratocystis epigloea Guerrero, Mycologia 63: 921. 1971. [as ‘epigloeum’]

Synonym: Ophiostoma epigloeum (Guerrero) de Hoog, Stud. Mycol. 7: 45. 1974.

Note: Forms part of group H in Sporothrix (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

17.

Sporothrix eucalyptigena (Barber & Crous) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817570.

Basionym: Ophiostoma eucalyptigena Barber & Crous, Persoonia 34: 193. 2015.

Note: Forms part of group H in Sporothrix (Fig. 2).

-

18.

Sporothrix eucastaneae (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817571.

Basionym: Ceratocystis eucastaneae R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 70: 856. 1978.

Notes: Ceratocystis eucastanea was treated by Upadhyay, 1981, Seifert et al., 1993 and De Beer et al. (2013) as synonym of O. stenoceras. However, our sequences of the ex-type isolate (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4) confirmed that this is a distinct species grouping close to O. aurorae in the S. gossypina complex.

-

19.

Sporothrix euskadiensis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817572.

Basionym: Ophiostoma euskadiense P. Romón et al., Mycologia 106: 125. 2014.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

20.

Sporothrix fumea (Kamgan et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817573.

Basionym: Ophiostoma fumeum Kamgan et al., Mycol. Progress 11: 527. 2012.

Note: Forms part of Group I (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

21.

Sporothrix fusiformis (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817574.

Basionym: Ophiostoma fusiforme Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf., Mycologia 96: 875. 2004.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

22.

Sporothrix gemella (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817575.

Basionym: Ophiostoma gemellus Roets, Z.W. de Beer & Crous, Mycologia 100: 504. 2008.

Note: Forms part of a Protea-associated subclade in the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

23.

Sporothrix globosa Marimon et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 45: 3203. 2007.

Synonym: Sporotrichum tropicale D. Panja et al., Indian Med. Gaz. 82: 202. 1947. [nom. inval., Art. 36.1]

Notes: Sporothrix globosa groups in the Pathogenic Clade. Sporotrichum tropicale was listed as synonym of S. schenckii by de Hoog (1974). The BT sequence for the original isolate of the latter species is identical to the S. globosa ex-type isolate (Fig. 3), while the LSU, ITS and CAL sequences of the two isolates respectively differ in 1, 2, and 1 positions (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 4). These two species should be considered synonyms as suggested by de Hoog (1974). Since the older name S. tropicale was invalidly published without a Latin diagnosis, the name S. globosa takes preference.

-

24.

Sporothrix gossypina (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817576.

Basionym: Ceratocystis gossypina R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 63: 12. 1971.

Synonym: Ophiostoma gossypinum (R.W. Davidson) J. Taylor, Mycopath. Mycol. Appl. 38: 112. 1976.

Notes: Davidson (1971) distinguished between O. gossypinum and C. gossypina var. robusta (= S. rossii, see below) based on perithecium morphology. Upadhyay (1981) treated both species as synonyms of O. stenoceras. Hausner & Reid (2003) showed that the LSU sequence of the ex-type isolate (ATCC 18999) of O. gossypinum differs from that of O. stenoceras. Our results confirmed that the three species are distinct, and that S. gossypina groups close to, but distinct from O. abietinum and related species in species complex 1 (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). As the first species to be described it becomes the name-bearing species of this complex.

-

25.

Sporothrix guttuliformis de Hoog, Persoonia 10: 62. 1978.

Notes: Sequences produced in the present study for the ex-type isolate of this species place it in S. inflata complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). However, earlier studies using the same isolate showed that this species was different from S. schenckii in physiology (de Hoog et al., 1985, de Hoog, 1993) and septal pore structure (Smith & Batenburg-Van der Vegte 1985). The ex-type isolate must thus be reconsidered carefully to determine whether it still corresponds with the original description.

-

26.

Sporothrix humicola de Mey. et al., Mycologia 100: 656. 2008.

Note: Groups in the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

27.

Sporothrix inflata de Hoog, Stud. Mycol. 7: 34. 1974.

Notes: Aghayeva et al. (2005) showed that isolates previously treated as S. inflata separated in four clades, one of which represented S. inflata s. str. This is the name-bearing species of the S. inflata complex in our analyses (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). The second group was subsequently described as representing a new species, S. brunneoviolacea, while the third group included the ex-type isolate of Humicola dimorphospora, which was transferred to Sporothrix by Madrid et al. (2010a) (see S. dimorphospora above). The fourth group, designated in our trees as ‘S. inflata 2’ in clade F (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), remains to be described as a new taxon.

-

28.

Sporothrix itsvo Musvuugwa et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109: 885. 2016.

Note: Forms part of the S. candida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

29.

Sporothrix lunata (Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817577.

Basionym: Ophiostoma lunatum Aghayeva & M.J. Wingf., Mycologia 96: 874. 2004.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

30.

Sporothrix luriei (Ajello & Kaplan) Marimon et al., Med. Mycol. 46: 624. 2008.

Basionym: S. schenckii var. luriei Ajello & Kaplan, Mykosen 12: 642. 1969.

Note: Forms part of the Pathogenic Clade (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

31.

Sporothrix mexicana Marimon et al., J. Clin. Microbiol. 45: 3203. 2007.

Note: Forms part of the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

32.

Sporothrix narcissi (Limber) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817578.

Basionym: Ophiostoma narcissi Limber, Phytopathology 40: 493. 1950.

Synonym: Ceratocystis narcissi (Limber) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 50. 1956.

Note: Forms part of the S. stenoceras complex.

-

33.

Sporothrix nebularis (P. Romón et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817579.

Basionym: Ophiostoma nebulare P. Romón et al., Mycologia 106: 125. 2014.

Note: Groups close to S. nigrograna in Group G (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

34.

Sporothrix nigrograna (Masuya) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817580.

Basionym: Ophiostoma nigrogranum Masuya, Mycoscience 45: 278. 2004.

Notes: This species was listed by Masuya et al. (2013) as part of the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex. De Beer et al. (2013) suggested an affiliation with Leptographium s. lat. rather than with Sporothrix s. str. based on the hyalorhinocladiella-like asexual morph and sheathed ascospores. However, our sequences of the ex-type isolate confirms it placement close to S. nebularis in Group G of Sporothrix (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

-

35.

Sporothrix pallida (Tubaki) Matsush., Icon. microfung. Matsush. lect. (Kobe): 143. 1975.

Basionym: Calcarisporium pallidum Tubaki, Nagaoa 5: 13. 1955.

Synonyms: Sporothrix albicans S.B. Saksena, Curr. Sci. 34: 318. 1965.

Sporothrix nivea Kreisel & F. Schauer, J. Basic Microbiol. 25: 654. 1985.

Notes: Sporothrix albicans and Calcarisporium pallidum were treated by de Hoog (1974) as synonyms of S. schenckii. However, De Meyer et al. (2008) showed that these two species grouped with S. nivea, distinct from S. schenckii. Sporothrix albicans and S. nivea were thus synonymised with S. pallida, the oldest of the three names. Our data confirmed the synonymy of these species (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Rodrigues et al. (2016) defined the lineage containing these and several other species as the S. pallida complex, a definition supported by our analyses.

-

36.

Sporothrix palmiculminata (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817581.

Basionym: Ophiostoma palmiculminatum Roets et al., Stud. Mycol. 55: 208. 2006.

Note: Groups in the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

37.

Sporothrix phasma (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817582.

Basionym: Ophiostoma phasma Roets, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf., Stud. Mycol. 55: 207. 2006.

Note: Forms a unique lineage between the other species complexes and groups in Sporothrix (Lineage E, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

38.

Sporothrix polyporicola (Constant. & Ryman) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817583.

Basionym: Ophiostoma polyporicola Constant. & Ryman, Mycotaxon 34: 637. 1989.

Note: Groups close to S. dimorphospora in Lineage F (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

39.

Sporothrix prolifera (Kowalski & Butin) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817584.

Basionym: Ceratocystis prolifera Kowalski & Butin, J. Phytopathol. 124: 245. 1989.

Synonym: Ophiostoma proliferum (Kowalski & Butin) Rulamort, Bull. Soc. Bot. Centre-Ouest, n.s. 21: 511. 1990.

Note: Groups in the S. gossypinum complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

40.

Sporothrix protearum G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Canad. J. Bot. 75: 364. 1997.

Synonym: Ophiostoma protearum G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Canad. J. Bot. 75: 363. 1997.

Note: Groups in a subclade including only species from Protea in the S. stenoceras complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

41.

Sporothrix protea-sedis (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817585.

Basionym: Ophiostoma protea-sedis Roets et al., Persoonia 24: 24. 2010.

Note: Groups in the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

42.

Sporothrix rapaneae Musvuugwa et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109: 885. 2016.

Note: Groups in the S. candida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

43.

Sporothrix rossii Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., nom. nov. MycoBank MB817586.

Synonym: Ceratocystis gossypina var. robusta R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 63: 13. 1971.

Notes: Davidson (1971) distinguished between Ceratocystis gossypina (now Sporothrix gossypina) and C. gossypina var. robusta based on perithecium morphology. Subsequent authors treated both species as synonyms of O. stenoceras (Upadhyay, 1981, Seifert et al., 1993). Hausner & Reid (2003) showed that O. gossypinum is distinct from O. stenoceras based on LSU data. Villarreal et al. (2005) produced an ITS sequence of the ex-type isolate of C. gossypina var. robusta, and because that sequence (AY924388) was identical to that of the ex-type of O. stenoceras, De Beer & Wingfield (2013) treated C. gossypina var. robusta as a synonym of O. stenoceras. However, LSU, ITS, BT and CAL sequences produced for the ex-holotype isolate in the present study clearly separated the two taxa (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4), necessitating a new combination for this name. To avoid confusion with Sporothrix gossypina and with Grosmannia robusta (R.C. Rob. & R.W. Davidson) Zipfel, Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf. [= Ophiostoma robustum (R.C. Rob. & R.W. Davidson) T.C. Harr.], we have designated a new epithet, based on the first name of the original author of this species, Ross W. Davidson. The description for S. rossii is the same as the original description of C. gossypina var. robusta (Davidson 1971), which is based on the holotype (RWD 609-D = BPI 595661) and ex-holotype isolate (CBS 116.78 = CMW 1118) from which sequences were obtained in the present study. Sporothrix rossii groups in the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

44.

Sporothrix schenckii Hektoen & C.F. Perkins, J. Exp. Med. 5: 77. 1900.

Synonyms: Sporotrichum beurmannii Matr. & Ramond, Compt. Rend. Hebd. Séances Mém. Soc. Biol. 2: 380. 1905.

Sporotrichopsis beurmannii (Matr. & Ramond) Gueguen. In De Beurmann & Gougerot, Archs Parasit. 15: 104. 1911. [nom. inval., Art. 38.1]

Sporothrix beurmannii (Matr. & Ramond) Meyer & Aird, J. Infect. Dis. 16: 399. 1915.

Dolichoascus schenckii Thibaut & Ansel. In Ansel & Thibaut, Compt. Rend. Hebd. Séances Acad. Sci. 270: 2173. 1970. [nom. inval., Art. 40.1]

Note 1: de Hoog (1974) listed several synonyms for S. schenckii from the medical literature predating 1940. The majority of those names are not listed here because material for these species is not available. Two exceptions are S. beurmannii and D. schenckii for reasons set out below.

Note 2: Sporotrichopsis, with S. beurmannii as type species, was published invalidly [Art. 38.1] as a provisional name by De Beurmann & Gougerot (1911) and was never validated. Davis (1920) argued convincingly that S. beurmannii should be treated as a synonym of S. schenckii. de Hoog (1974) followed this suggestion. The implication of the species synonymy is that Sporotrichopsis, if valid, would have been treated as a synonym of Sporothrix.

Note 3: Dolichoascus schenckii, the type species for Dolichoascus, was not validly published (Ansel & Thibaut 1970) because a holotype was not indicated [Art. 40.1] also resulting in an invalid genus name. Ansel & Thibaut (1970) and Thibaut (1972) suggested that Dolichoascus (Endomycetaceae) represented the sexual morph of S. schenckii due to the presence of what they described as endogenous ascospores. However, Mariat & Diez (1971) studied the isolate (CBS 938.72) of Ansel & Thibaut (1970) and suggested that the “ascospores” were in fact endoconidia. de Hoog (1974) argued that the name Dolichoascus could thus not be used for an anamorph genus based on the prevailing dual nomenclature principles dictated by Article 59 of the Seattle Code (Stafleu 1972). At present, the emended Article 59 of the Melbourne Code (McNeill et al. 2012) permits the use of the name Dolichoascus whether a sexual state is present or not. Because the ex-type isolate is still viable, lectotypification [Art. 9.2] and validation of the species and genus would be possible. However, Marimon et al. (2007) and Zhang et al. (2015) respectively produced a CAL and an ITS sequence for the D. schenckii isolate, confirming that it is conspecific with the ex-type of S. schenckii (Fig. 2, Fig. 4). There is consequently no need for lectotypification or validation of the species or genus, as Dolichoascus becomes a valid synonym for Sporothrix.

Note 4: Sporothrix schenckii was treated for some years as asexual morph of O. stenoceras (Taylor, 1970, Mariat, 1971, de Hoog, 1974). However, De Beer et al. (2003) showed that the two species were distinct based on ITS sequences, and this was confirmed in the present study with LSU, ITS, BT and CAL sequences (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). No sexual morph is currently known for S. schenckii.

-

45.

Sporothrix splendens G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 98: 373. 1994.

Synonym: Ophiostoma splendens G.J. Marais & M.J. Wingf., Mycol. Res. 98: 371. 1994.

Note: Forms part of the S. stenoceras complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

46.

Sporothrix stenoceras (Robak) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817587.

Basionym: Ceratostomella stenoceras Robak, Nyt Mag. Naturvid. Oslo 71: 214. 1932.

Synonyms: Ophiostoma stenoceras (Robak) Nannf. In Melin & Nannf., Svenska SkogsvFör. Tidskr. 32: 408. 1934.

Ceratocystis stenoceras (Robak) C. Moreau, Rev. Mycol. (Paris) Suppl. Col. 17: 22. 1952.

Ophiostoma albidum Math.-Käärik, Medd. Skogsforskninginst. 43: 52. 1953.

Ceratocystis albida (Math.-Käärik) J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 48. 1956.

Note 1: The asexual morph of O. stenoceras has often been referred to as S. schenckii, but De Beer et al. (2003) showed that the two species are distinct. Our analyses of all four gene regions supported the separation of the two species (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Note 2: Ophiostoma albidum was treated as synonym of O. stenoceras by de Hoog, 1974, Upadhyay, 1981 and Seifert et al. (1993). Hausner & Reid (2003) and De Beer et al. (2003) respectively showed that LSU and ITS sequences of O. albidum are identical to those of O. stenoceras (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). BT and CAL data produced in the present study for the ex-type isolates of both these species (Fig. 3, Fig. 4), confirmed that O. albidum is a synonym of S. stenoceras.

-

47.

Sporothrix stylites de Mey. et al., Mycologia 100: 656. 2008.

Note: Forms part of the S. pallida complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

48.

Sporothrix thermara (J.A. van der Linde et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MycoBank MB817619.

Basionym: Ophiostoma thermarum J.A. van der Linde et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109: 595. 2016.

Note: Forms part of Group H (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

49.

Sporothrix uta Musvuugwa et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109: 887. 2016.

Note: Forms part of the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

50.

Sporothrix variecibatus Roets et al., Mycologia 100: 506. 2008.

Note: Forms part the S. gossypina complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

-

51.

Sporothrix zambiensis (Roets et al.) Z.W. de Beer, T.A. Duong & M.J. Wingf., comb. nov. MB817588.

Basionym: Ophiostoma zambiense Roets et al., Persoonia 24: 24. 2010. [as ‘zambiensis’]

Note: Forms part the S. stenoceras complex (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Sporothrix spp. and species with sporothrix-like asexual morphs currently classified in other genera of the Ophiostomatales

This list includes species of Ophiostomatales where the sporothrix-like asexual morphs were provided with binomials in Sporothrix under the dual nomenclature system, or where our analyses confirmed the generic placement outside Sporothrix for the first time. Additional species with sporothrix-like asexual morphs but without a binomial in Sporothrix, and previously classified in other genera in the Ophiostomatales based on DNA sequence data, are listed by De Beer et al. (2013).

-

1.

Ophiostoma angusticollis (E.F. Wright & H.D. Griffin) M. Villarreal, Mycotaxon 92: 262. 2005.

Basionym: Ceratocystis angusticollis E.F. Wright & H.D. Griffin, Canad. J. Bot. 46: 697. 1968.

Notes: Our LSU analyses suggest that O. angusticollis groups with O. denticulatum in a distinct lineage (Fig. 1) in Ophiostoma s. str. This supports the placement of the species by Villarreal et al. (2005) and De Beer & Wingfield (2013), who also showed that it groups with O. sejunctum based on ITS sequences. However, the isolate does not represent the holotype and typification needs to be resolved before a final conclusion can be made regarding the generic placement of this species.

-

2.

Ophiostoma denticulatum (R.W. Davidson) Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf. In Seifert et al., The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: 252. 2013.

Basionym: Ceratocystis denticulata R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 71: 1088. 1979.

Notes: De Beer et al. (2013) suggested that O. denticulatum might belong in the S. schenckii–O. stenoceras complex based on morphology. However, the species grouped with O. angusticollis distinct from Sporothrix in Ophiostoma s. str. in our LSU analyses (Fig. 1). In addition, its BT gene contains intron 4 (Table 2), which is absent in all species of Sporothrix.

-

3.

Ophiostoma macrosporum (Francke-Grosm.) Z.W. de Beer & M.J. Wingf. In Seifert et al., The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: 256. 2013.

Basionym: Trichosporum tingens var. macrosporum Francke-Grosm., Medd. Skogsforskninginst. 41: 27. 1952 [as ‘Trichosporium tingens var. macrosporum’]

Synonyms: Ambrosiella macrospora (Francke-Grosm.) L.R. Batra, Mycologia 59: 980. 1967.

Hyalorhinocladiella macrospora (Francke-Grosm.) TC. Harr. In Harrington et al., Mycotaxon 111: 355. 2010.

Note: Forms a distinct lineage outside Sporothrix and close to O. piliferum in Ophiostoma s. str. (Fig. 1).

-

4.

Ophiostoma ponderosae (T.E. Hinds & R.W. Davidson) Hausner et al., Canad. J. Bot. 71: 1264. 1993.

Basionym: Ceratocystis ponderosae T.E. Hinds & R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 67: 715. 1975.

Notes: According to De Beer et al. (2003) the ex-type of O. ponderosae (ATCC 26665 = RWD 900 = C87) had an ITS sequence identical to O. stenoceras. The original isolate died in our collection and we re-ordered the ex-type from ATCC (ATCC 26665 = RWD 900 = CMW 37953). The LSU sequence of the fresh isolate placed it close to O. piliferum in Ophiostoma s. str. (Fig. 1). Consequently, we do not accept the synonymy of O. ponderosae with O. stenoceras, exclude it from Sporothrix and consider it a distinct species of Ophiostoma s. str. The LSU and ITS sequences of another O. ponderosae isolate (CBS 496.77 = RWD 899) from the study of Hinds & Davidson (1975), grouped in the O. pluriannulatum complex (Fig. 1). It appears to represent an undescribed taxon in that complex, but for the interim it is labelled as ‘O. ponderosae 2’.

-

5.

Sporothrix lignivora de Mey. et al., Mycologia 100: 657. 2008.

Notes: This species groups in a distinct lineage of the Ophiostomatales, previously referred to as the Sporothrix lignivora complex, but recently defined as a new genus, Hawksworthiomyces (Fig. 1) (De Beer et al. 2016). The current name species name is Hawksworthiomyces lignivora (de Mey. et al.) Z.W. de Beer et al. (De Beer et al. 2016).

-

6.

Sporothrix pirina (Goid.) Morelet, Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Arch. Toulon et du Var 44: 110. 1992. [as ‘pirinum’]

Basionym: Hyalodendron pirinum Goid., Boll. R. Staz. Patalog. Veget. Roma, N.S. 15: 136. 1935.

Note: This species was described as the anamorph of Ophiostoma catonianum (Goid.) Goid. and is currently treated as synonym of the latter species in the O. ulmi complex in Ophiostoma s. str. (Grobbelaar et al., 2009, De Beer et al., 2013).

-

7.

Sporothrix roboris (Georgescu & Teodoru) Grobbelaar et al., Mycol. Progress 8: 233. 2009.

Basionym: Hyalodendron roboris Georgescu & Teodoru, Anal. Inst. Cerc. Exp. For. Rom., Ser 1. 11: 209. 1948.

Notes: Sporothrix roboris was described as the asexual morph of Ophiostoma roboris Georgescu & Teodoru (Grobbelaar et al. 2009). Both O. roboris and S. roboris are now treated as synonyms of Ophiostoma quercus (Georgev.) Nannf. in the O. ulmi complex of Ophiostoma s. str. (De Beer and Wingfield, 2013, De Beer et al., 2013).

-

8.

Sporothrix subannulata Livingston & R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 79: 145. 1987.

Note: Initially described as asexual morph for Ophiostoma subannulatum Livingston & R.W. Davidson, but currently treated as its formal synonym in Ophiostoma s. str. (De Beer et al., 2013, De Beer and Wingfield, 2013).

Sporothrix spp. and species with sporothrix-like asexual morphs, but of uncertain generic status in the Ophiostomatales

This list includes species for which sequence data place them in the Ophiostomatales, but not in one of the currently accepted genera. Taxa with sporothrix-like asexual morphs that resemble Ophiostomatales, but for which no sequence data are available are also included.

-

1.

Ophiostoma ambrosium (Bakshi) Hausner, J. Reid & Klassen, Canad. J. Bot. 71: 1264. 1993.

Basionym: Ceratocystis ambrosia Bakshi, Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 33: 116. 1950.

Notes: Griffin, 1968, Upadhyay, 1981, Hutchison and Reid, 1988 and Seifert et al. (1993) treated O. ambrosium as synonym of O. piliferum, while Hunt (1956) and de Hoog (1974) treated it as a distinct species. In the phylogeny of De Beer & Wingfield (2013), a very short LSU sequence of O. ambrosium from Hausner et al. (1993b) grouped with O. grande in a lineage. We did not include the O. ambrosium sequence in our analyses because it was inordinately short, but O. grande grouped distinct from Sporothrix and all other genera in our analyses (Lineage B, Fig. 1).

-

2.

Ophiostoma coronatum (Olchow. & J. Reid) M. Villarreal, Mycotaxon 92: 263. 2005.

Basionym: Ceratocystis coronata Olchow. & J. Reid, Canad. J. Bot. 52: 1705. 1974.

Notes: Upadhyay (1981) treated O. coronatum as synonym of O. tenellum, but this was rejected by Hutchison & Reid (1988) because of differences in the ascospore shape. Our data support those of Villarreal et al. (2005) and De Beer & Wingfield (2013) that separated the two species. These species group together with O. nigricarpum, O. rostrocoronatum and O. tenellum in Lineage D (Fig. 1), at present referred to as the O. tenellum complex (De Beer & Wingfield 2013). All the species in this complex differ from those in Sporothrix s. str. in that they have CAL intron 5, which is lacking in true Sporothrix spp. (Table 2). The generic status of all species in the O. tenellum complex should be reconsidered because the complex grouped distinct from Ophiostoma s. str. and other genera in the Ophiostomatales (Fig. 1).

-

3.

Ophiostoma grande Samuels & E. Müll., Sydowia 31: 176. 1978.

Notes: This species grouped with O. ambrosium in a lineage distinct from Sporothrix in the study of De Beer & Wingfield (2013). The O. ambrosium sequence was not included in our analyses (see above), but O. grande formed a lineage (B, Fig. 1) distinct from Sporothrix and all other genera in our analyses. We could not amplify the BT gene region for this isolate, but its CAL intron arrangement was similar to that of S. brunneoviolacea, and thus distinct from all other Sporothrix spp. (Table 2).

-

4.

Ophiostoma grandicarpum (Kowalski & Butin) Rulamort, Bull. Soc. Bot. Centre-Ouest, n.s. 21: 511. 1990. [as ‘grandicarpa’]

Basionym: Ceratocystis grandicarpa Kowalski & Butin, J. Phytopathol. 124: 243. 1989.

Notes: Kowalski & Butin (1989) reported two synasexual morphs in their cultures of this species, but according to Seifert et al. (1993), these appear to represent the noncatenate and catenate forms of a sporothrix-like asexual morph. The LSU sequence of the ex-type isolate of this species, together with O. microsporum, form a lineage of uncertain generic affiliation in the Ophiostomatales (Lineage A, Fig. 1), distinct from Sporothrix s. str. This supports the unique placement of the species by De Beer & Wingfield (2013) based on ITS. The BT sequence was too divergent to include in our analyses, but the intron composition (3/-/5) reflected those of many Sporothrix spp. as well as other Ophiostomatales (Table 2).

-

5.

Ophiostoma longicollum Masuya, Mycoscience 39: 349. 1998.

Notes: The morphology of this species from Quercus infested by Platypus quercivorus in Japan suggests a relatedness with species such as S. stenoceras or O. nigricarpum. Sequence data are needed to confirm its correct phylogenetic placement.

-

6.

Ophiostoma megalobrunneum (R.W. Davidson & Toole) de Hoog & Scheffer, Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Basionym: Ceratocystis megalobrunnea R.W. Davidson & Toole, Mycologia 56: 796. 1964.

Notes: This species was isolated from oak sapwood in the USA. Ascospore and asexual morph morphology suggest that this might be a species of Sporothrix, but it should be re-examined and sequenced to confirm its placement.

-

7.

Ophiostoma microsporum Arx, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 18: 211. 1952.

Synonyms: Ceratostomella microspora R.W. Davidson, Mycologia 34: 650. 1942. [nom. illegit., later homonym for Cs. microspora Ellis & Everh.]

Ceratocystis perparvispora J. Hunt, Lloydia 19: 46. 1956. [superfluous nom. nov.]

Ceratocystis microspora (R.W. Davidson) R.W. Davidson & Aoshima, Ph.D. thesis, University of Tokyo: 20. 1965 [nom. inval.]

Ceratocystis microspora (Arx) R.W. Davidson, J. Col.-Wyom. Acad. Sci. 6: 16. 1969.

Notes: De Beer et al. (2013) discussed the confusing taxonomic history of this species. De Beer & Wingfield included a short LSU sequence for isolate CBS 412.77 generated by Hausner et al. (1993b). Our LSU sequence of the ex-neotype isolate (CBS 440.69 = CMW 17152) designated by Davidson & Kuhlman (1978), is identical to the sequence of Hausner et al. (1993b). It groups with O. grandicarpum in Lineage A (Fig. 1), distinct from Sporothrix and all other genera and was thus not included in the other analyses. The name O. microsporum should not be confused with Leptographium microsporum R.W. Davidson, neither with Ceratostomella microspora (De Beer et al. 2013).

-

8.

Ophiostoma nigricarpum (R.W. Davidson) de Hoog, Stud. Mycol. 7: 62. 1974. [as ‘nigrocarpum’]

Basionym: Ceratocystis nigrocarpa R.W. Davidson, Mycopath. Mycol. Appl. 28: 276. 1966.

Notes: De Beer et al. (2003) treated several isolates of O. abietinum incorrectly as O. nigricarpum. Aghayeva et al. (2004) showed that the ex-type isolate of O. nigricarpum is distinct from O. abietinum. Ophiostoma nigricarpum forms part of the O. tenellum complex (Lineage D, Fig. 1) (see Notes under O. coronatum).

-

9.

Ophiostoma noisomeae Musvuugwa et al., Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 109: 887. 2016.

Notes: Musvuugwa et al. (2016) recently described this species from wood and bark of Rapanea in South Africa, and recognised that the species grouped outside of Sporothrix, Ophiostoma s. str. and other genera in the Ophiostomatales, similar to its placement in our LSU tree (Lineage C, Fig. 1). However, they did not consider this to be sufficient evidence to establish a distinct, monotypic genus. The BT intron composition of O. noisomeae is is 3/4/5, while that of Sporothrix is 3/-/5 or -/-/5 (Table 2). The group served as a convenient outgroup in our analyses (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4), but its generic status should be reconsidered.

-

10.

Ophiostoma persicinum Govi & Di Caro, Ann. Speriment. Agraria, n.s. 7: 1644. 1953.

Notes: The morphology of this species from peach tree roots in Italy suggests that it belongs in Sporothrix s. str. We could not locate type material for this species and recommend neotypification to enable generic placement based on DNA sequence data.

-

11.

Ophiostoma rostrocoronatum (R.W. Davidson & Eslyn) de Hoog & Scheffer, Mycologia 76: 297. 1984.

Basionym: Ceratocystis rostrocoronata R.W. Davidson & Eslyn. In Eslyn & Davidson, Mem. N.Y. Bot. Gard. 28: 50. 1976.