ABSTRACT

In the plant-beneficial bacterium Pseudomonas putida KT2440, three genes have been identified that encode posttranscriptional regulators of the CsrA/RsmA family. Their regulatory roles in the motile and sessile lifestyles of P. putida have been investigated by generating single-, double-, and triple-null mutants and by overexpressing each protein (RsmA, RsmE, and RsmI) in different genetic backgrounds. The rsm triple mutant shows reduced swimming and swarming motilities and increased biofilm formation, whereas overexpression of RsmE or RsmI results in reduced bacterial attachment. However, biofilms formed on glass surfaces by the triple mutant are more labile than those of the wild-type strain and are easily detached from the surface, a phenomenon that is not observed on plastic surfaces. Analysis of the expression of adhesins and exopolysaccharides in the different genetic backgrounds suggests that the biofilm phenotypes are due to alterations in the composition of the extracellular matrix and in the timing of synthesis of its elements. We have also studied the expression patterns of Rsm proteins and obtained data that indicate the existence of autoregulation mechanisms.

IMPORTANCE Proteins of the CsrA/RsmA family function as global regulators in different bacteria. More than one of these proteins is present in certain species. In this study, all of the RsmA homologs in P. putida are characterized and globally taken into account to investigate their roles in controlling bacterial lifestyles and the regulatory interactions among them. The results offer new perspectives on how biofilm formation is modulated in this environmentally relevant bacterium.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins belonging to the CsrA/RsmA family are small (less than 7 kDa) RNA-binding proteins that play key roles in the regulation of gene expression in diverse Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. CsrA (carbon storage regulator) was first described in Escherichia coli (1, 2), where it plays a major role in controlling the intracellular carbon flux, acting as a negative regulator of glycogen metabolism and several enzymes involved in central carbohydrate metabolism (3, 4). Members of the CsrA/RsmA family have subsequently been found to be important elements in global posttranscriptional regulation in many other bacterial genera. In the opportunistic human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the CsrA homolog RsmA (repressor of secondary metabolism) negatively regulates the production of virulence determinants, such as hydrogen cyanide, pyocyanin, or LecA (PA-1L) lectin, as well as N-acylhomoserine lactone (AHL) quorum-sensing signal molecules (5, 6). In this bacterium, RsmA also represses the translation of the psl operon, responsible for the synthesis of one of the two main exopolysaccharides (EPSs) that contribute to the extracellular matrix of biofilms in nonmucoid strains of P. aeruginosa (7). RsmA promotes the planktonic lifestyle of P. aeruginosa, functioning in opposition to the increase in the second messenger c-di-GMP, which leads to a sessile lifestyle, and some of the molecular elements connecting the two regulatory networks are being characterized (reference 8 and references therein).

RsmA homologs act posttranscriptionally, often by binding to mRNA at or near the ribosome-binding site, thus modulating translation (9, 10). For example, in Pseudomonas fluorescens, RsmA represses the production of hydrogen cyanide during exponential growth by reducing the translation rate of hcnA, the gene coding for hydrogen cyanide synthase. A specific sequence near the ribosome-binding site was shown to be required for RsmA activity to be evident on hcnA::lacZ translation (11). In E. coli, CsrA mediates posttranscriptional repression of glycogen biosynthesis by binding to the 5′ leader transcript of glgC and inhibiting its translation (12). CsrA can also act directly or indirectly as a positive regulator of gene expression: in E. coli, it activates genes involved in glycolysis and the glyoxylate shunt (13) and in flagellar motility. In the last case, binding of CsrA to a 5′segment of flhDC mRNA stimulates its translation and extends its half-life (14).

The effects of RsmA/CsrA are relieved by small regulatory RNA molecules that sequester multiple units of the proteins, thereby modulating their activity. Such antagonistic small RNAs include CsrB and CsrC in E. coli (1, 15); RsmB in Erwinia carotovora (16); and RsmX, RsmY, and RsmZ in P. fluorescens (17, 18). This kind of posttranscriptional control may facilitate rapid, potentially reversible regulation of diverse cellular functions.

The RsmA family proteins and their cognate small RNAs described so far in Pseudomonas are part of the GacS/GacA signal transduction pathway, which operates an important metabolic switch from primary to secondary metabolism in many Gram-negative bacteria and also affects enzyme synthesis and secretion (11, 19, 20). GacS is a sensor histidine kinase that responds to an as yet unidentified signal and phosphorylates the response regulator GacA, causing its activation. In P. aeruginosa, GacA positively regulates the quorum-sensing machinery and the expression of several virulence factors via a mechanism involving the participation of RsmA as a negative-control element (5, 21). The main regulatory targets of GacA correspond to the small RNAs of the rsmX-rsmY-rsmZ family that interact with RsmA (22).

In this study, we analyzed the roles and expression of the three RsmA family proteins present in the plant-beneficial bacterium Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Our results indicate that these proteins have different effects on motility, biofilm formation, and dispersal of P. putida KT2440, altering the expression of adhesins and exopolysaccharides. These effects may depend on regulatory interactions between the three Rsm proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table 1. P. putida KT2440 is a plasmid-free derivative of P. putida mt-2, which was isolated from a field planted with vegetables and whose genome is completely sequenced (23, 24). Fluorescently labeled strains with a single chromosomal copy of mCherry were obtained by conjugation using the plasmid miniTn7Ptac-mChe (25) as detailed below. E. coli and P. putida strains were routinely grown at 37°C and 30°C, respectively, in LB medium (26) under orbital shaking (200 rpm). M9 minimal medium (27) was supplemented with trace elements (28) and glucose or citrate at the concentrations indicated in each case. For pyoverdine quantification, King's B medium was used (29). When appropriate, antibiotics were added to the media at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml (E. coli) or 100 μg/ml (P. putida); and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml or 20 μg/ml (as indicated). Cell growth was followed by measuring turbidity at 600 nm (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]) or 660 nm (OD660), except for experiments done in a BioScreen apparatus with a wide-band filter (450 to 580 nm).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype/relevant characteristicsa | Reference/source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| CC118λpir | Rifr λpir | 33 |

| DH5α | supE44 lacU169(ϕ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 (rk− mk−) recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | 50 |

| HB101 | Host of helper plasmid pRK600 | V. de Lorenzo |

| P. putida | ||

| KT2440 | Wild type; derivative of P. putida mt-2 cured of pWW0 | 23 |

| pvdS | Mutant in pvdS; defective in pyoverdine synthesis | 39 |

| ΔI | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_1746 (rsmI) | This study |

| ΔE | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_3832 (rsmE) | This study |

| ΔA | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_4472 (rsmA) | This study |

| ΔIE | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_1746 and PP_3832 | This study |

| ΔEA | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_3832 and PP_4472 | This study |

| ΔIA | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_1746 and PP_4472 | This study |

| ΔIEA | Null mutant derivative of KT2440 in PP_1746, PP_3832 and PP_4472 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM-T Easy | Apr; PCR cloning vector with β-galactosidase α-complementation | Promega |

| PCR2.1 TOPO | Kmr; PCR cloning vector with β-galactosidase α-complementation | Invitrogen |

| pKNG101 | Smr; oriR6K mobRK2 sacBR | 34 |

| pMP220-BamHI | Tcr; pMP220 with deletion of a 238-bp BamHI fragment, removing the ribosome-binding site and 52 codons of cat that precede ′lacZ | 35 |

| RK600 | Cmr; mob tra | V. De Lorenzo |

| pUC18Not | Apr; cloning vector; MCS of pUC18 flanked by NotI sites | 33 |

| pME6032 | Tcr; pVS1-p15A derivative; broad-host-range lacIq-Ptac expression vector | 17 |

| pMMG1 | Tcr; transcriptional fusion lapF::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | 43 |

| pMMGA | Tcr; transcriptional fusion lapA::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | 42 |

| pMIR125 | Tcr; transcriptional fusion algD::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | 51 |

| pMP-bcs | Tcr; transcriptional fusion PP_2629::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | |

| pMP-pea | Tcr; transcriptional fusion PP_3132::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | 51 |

| pMP-peb | Tcr; transcriptional fusion PP_1795::′lacZ containing RBS and first codons | 51 |

| pOHR14 | Apr; pUC18NotI derivative with 1.9-kb NotI fragment containing the rsmA null allele | This study |

| pOHR20 | Smr; pKNG101 derivative for the rsmA null allele replacement with the 1.9-kb NotI fragment of pOHR14 cloned at the same site of pKNG101 | This study |

| pOHR30 | Apr; pUC18NotI derivative with 1.7-kb NotI fragment containing the rsmI null allele | This study |

| pOHR33 | Smr; pKNG101 derivative for the rsmI null allele replacement with the 1.7-kb NotI fragment of pOHR30 cloned at the same site of pKNG101 | |

| pOHR32 | Apr; pUC18NotI derivative with 2-kb NotI fragment containing the rsmE null allele | This study |

| pOHR34 | Smr; pKNG101 derivative for the rsmE null allele replacement with the 2-kb NotI fragment of pOHR32 cloned at the same site of pKNG101 | This study |

| pME6032-rsmA | Tcr; pME6032 derivative for the ectopic expression of rsmA under the control of laclq-Ptac | This study |

| pME6032-rsmE | Tcr; pME6032 derivative for the ectopic expression of rsmE under the control of laclq-Ptac | This study |

| pME6032-rsmI | Tcr; pME6032 derivative for the ectopic expression of rsmI under the control of laclq-Ptac | This study |

| pOHR46 | Tcr; pMP220-BamHI derivative containing translational fusion RsmI-LacZ | This study |

| pOHR47 | Tcr; pMP220-BamHI derivative containing translational fusion RsmE-LacZ (with proximal promoter) | This study |

| pOHR48 | Tcr; pMP220-BamHI derivative containing translational fusion RsmE-LacZ (with proximal and distal promoters) | This study |

| pOHR52 | Tcr; pMP220-BamHI derivative containing translational fusion RsmA-LacZ | This study |

Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Km, kanamycin; Rif, rifampin; Sm, streptomycin; Tc, tetracycline; MCS, multicloning site; RBS, ribosome-binding site.

DNA techniques.

Preparation of chromosomal DNA, digestion with restriction enzymes, dephosphorylation, ligation, and electrophoresis were carried out using standard methods (27, 30) and following the manufacturers' instructions (Roche and New England BioLabs). Plasmid DNA isolation and recovery of DNA fragments from agarose gels were done with Qiagen miniprep and gel extraction kits, respectively. The DIG-DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche) was used for Southern blots, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Electrotransformation of freshly plated Pseudomonas cells was performed as previously described (31). For PCR amplifications, Expand High Fidelity polymerase (Roche) was used if amplicons were used in further cloning.

Conjugation.

Overnight cultures (0.5 ml) of donor, helper, and recipient bacteria were mixed, centrifuged (12,000 rpm; 2 min), washed with 1 ml of fresh LB medium to remove antibiotic traces, and resuspended in 50 μl of LB medium. The mixture was spotted onto a 0.22-μm filter placed on an LB plate and incubated overnight at 30°C. The mating mixture was then suspended in 2 ml of M9 salts and plated in M9 medium with 15 mM sodium citrate to counterselect E. coli strains and with the corresponding antibiotics for transconjugant selection. For strains harboring miniTn7Ptac-mChe, the presence of a chromosomal copy of the transposon at an extragenic location near glmS was checked by PCR, as described previously (32).

Generation of null mutants.

The general strategy for the construction of null mutants consisted of replacement by homologous recombination of the wild-type allele with a null allele. Fragments (0.7 to 1 kb) of the regions flanking each rsm gene were amplified by PCR with oligonucleotides containing unique restriction sites (Table 2) and then cloned into pGEM-T Easy or pCR2.1-TOPO. The absence of missense mutations in the PCR amplicons was confirmed by sequencing. The null allele was first cloned in pUC18Not (33) and subsequently subcloned in the NotI site of plasmid pKNG101 (34), which is unable to replicate in Pseudomonas. The derivative plasmids of pKNG101 containing the null mutations were mobilized from E. coli CC118 λpir into P. putida KT2440 by conjugation as described above, using HB101(pRK600) as a helper. Merodiploid exconjugants were first selected in minimal medium with citrate and streptomycin and then incubated in LB medium supplied with 12% sucrose to obtain clones in which a second recombination event had removed the plasmid backbone. Sm-sensitive clones were repurified, and the presence of the null mutations was checked by PCR, followed by sequencing of the corresponding chromosomal region and Southern blotting. The nomenclature of the mutants in more than one locus indicates the order in which the null alleles were introduced.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this work

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′)a | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| PP_4472UpF | TTGAGCTCCAGCATCACTACCCTGGGTC | rsmA null mutant construction |

| PP_4472UpR | TGGGATCCCATTCAGGGGTAACAGTCTTGG | |

| PP_4472DwF | TCGGATCCGAAGGATGAAGAGCCAAGCC | |

| PP_4472DwR | TCGGATCCGATTGTTGTGGATGGGAAAGC | |

| PP_3832UpF | GAATTCCGACCAGCACAAATACGGG | rsmE null mutant construction |

| PP_3832UpR | TCTAGACTCCTTGGTGATGTATAAGTCCG | |

| PP_3832DwF | TCTAGAGAAGACACACACTGAGCGTCAC | |

| PP_3832DwR | AAGCTTGACATCATTGGGCCTGGC | |

| PP_1746UpF | GAATTCCCGATGTCAACGAAGCC | rsmI null mutant construction |

| PP_1746UpR | TCTAGAGTTCCGATCCTCCTGCG | |

| PP_1746DwF | TCTAGAGCAGAGCAAGGCCTGAAG | |

| PP_1746DwR | AAGCTTCTGGCGTAGCGGCATTG | |

| PP_4472HistagF | GAATTCATGcatcatcatcatcatATGTTGATTCTGACTCGTCG | 189-bp EcoRI/XhoI fragment for rsmA ectopic expression |

| PP_4472HistagR | CTCGAGCTATTATAAAGGCTTGGCTCTTCATCC | |

| PP_3832HistagF | GAATTCATGcatcatcatcatcatATGCTGATACTCACCCGTAAG | 198-bp EcoRI/XhoI fragment for rsmE ectopic expression |

| PP_3832HistagR | CTCGAGCTATTATCAGTGTGTGTCTTCGTGTTTC | |

| PP_1746HistagF | GAATTCATGcatcatcatcatcatATGCTGGTAATAGGGCGC | 180-bp EcoRI/XhoI fragment for rsmI ectopic expression |

| PP_1746HistagR | CTCGAGCTATTATCAGGCCTTGCTCTGC | |

| PP_4472GSPR1 | GAATCAACATAGCTTTCTCCTTACGCA | +1 determination of rsmA by RACE-PCR |

| PP_4472GSPR2 | TTGCCTTTGACGCCAA | |

| PP_3832GSPR1 | AGTGTGTGTCTTCGTGTTTCTCC | +1 determination of rsmE by RACE-PCR |

| PP_3832GSPR2 | TCAGTTAATAGGCACCTG | |

| PP_1746GSPR1 | AGGCCTTGCTCTGCTTGGAC | +1 determination of rsmI by RACE-PCR |

| PP_1746GSPR2 | GACCTGGAAAGCCAGCAAT | |

| PP_4472PromF | GGATCCGCTTCCAGGGCGTC | RsmA-LacZ fusion |

| PP_4472PromR | GGATCCCGACGAGTCAGAATCAA | |

| PP_3832ShortPromF | GGATCCCCGTTGACGGTTTGC | RsmEP2-LacZ fusion (proximal promoter) |

| PP_3832ShortPromR | GGATCCCCAACCTTACGGGTG | |

| PP_3832LargePromF | GGATCCGGCCTTGCTGTTGTTTC | RsmEP1P2-LacZ fusion (proximal + distal promoters) |

| PP_3832ShortPromR | GGATCCCCAACCTTACGGGTG | |

| PP_1746PromF | GGATCCGCGGCTGTATGACG | RsmI-LacZ fusion |

| PP_1746PromR | GGATCCCCTACTTCGCGCCCTA | |

| qRTAlgF | GCTTCCTCGAAGAGCTGAA | qRT-PCR; alg cluster (PP_1277; algA)b |

| qRTAlgR | CTCCATCACCGCATAGTCA | |

| qRTPebF | GCAATGTCTCCACAGGCAC | qRT-PCR; peb cluster (PP_1795)b |

| qRTPebR | TCATCTGATTGGCGACCAG | |

| qRTCelF | GTCGAGAGCAGCCAGCTTC | qRT-PCR; bcs cluster (PP_2629)b |

| qRTCelR | GCCTCATACAGTGCCAGCTC | |

| qRTPeaF | TGCTCAGCACGCCGACACG | qRT-PCR; pea cluster (PP_3132)b |

| qRTPeaR | GGTCTCGCTGTTCAGCA | |

| qRT16SF | AAAGCCTGATCCAGCCAT | qRT-PCR control 16S rRNA |

| qRT16SR | GAAATTCCACCACCCTCTACC |

Restriction sites inserted in the primer for the cloning strategy are underlined; 6× histidine tail is in lowercase.

The specific loci are given.

Overexpression of Rsm proteins.

Plasmid pME6032 (17) was used to overexpress RsmI, RsmE, and RsmA. The three genes were amplified from P. putida KT2440 chromosomal DNA by PCR using oligonucleotides PP1746HistagF and PP1746HistagR, PP_3832HistagF and PP_3832HistagR, and PP_4472HistagF and PP_4472HistagR, respectively (Table 2); digested by EcoRI and XhoI; and inserted into EcoRI/XhoI-cut pME6032 to obtain pOHR40, pOHR38, and pOHR37, respectively. The integrity of all the constructs was verified by sequencing to discard any mutation in the PCR amplicons.

Construction of Rsm-LacZ translational fusions.

Translational fusions were generated by PCR amplification of a fragment covering the promoter regions plus initiation codons of rsmI, rsmE, and rsmA designed to ensure in-frame cloning in pMP220-BamHI (35). The primers used are listed in Table 2. PCR amplicons of 222 bp (for RsmI-LacZ), 204 bp (for RsmE-LacZ with the proximal promoter), 340 bp (for RsmE-LacZ with the distal and proximal promoters), and 1,000 bp (RsmA-LacZ) containing the ribosome-binding sites, and the first 7 to 9 codons of each gene were cloned in pCR2.1-TOPO and sequenced to ensure the absence of mutations, followed by digestion with BamHI and subsequent cloning into the same site of pMP220-BamHI to yield pOHR46, pOHR47, pOHR48, and pOHR52, respectively.

RNA purification.

Bacterial cells grown in liquid LB medium were harvested at the indicated times by centrifugation, immediately frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Alternatively, cells were collected from patches grown on LB plates for 24 or 48 h and resuspended in M9 salts prior to centrifugation and freezing. Total RNA from the mutants and the wild type was extracted by using TRI reagent (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer, except that Tripure isolation reagent was preheated at 70°C, followed by purification with an RNeasy purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA traces were then removed from RNA samples with RNase-free DNase I (Turbo RNA-free; Ambion), as specified by the supplier. The RNA concentration was determined with a NanoDrop ND1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA), its integrity was assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the absence of any residual DNA was checked by PCR.

qRT-PCR.

Expression analyses by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed using iCycler Iq (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with total RNA preparations obtained from three independent cultures (three biological replicates). Total RNA (1 μg) treated with Turbo DNA free (Ambion) was retrotranscribed to cDNA with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using random hexamers as primers. Template cDNAs from the experimental and reference samples were amplified in triplicate using the primers listed in Table 2. Each reaction mixture contained 2 μl of a dilution of the target cDNA (1:10 to 1:10,000) and 23 μl of Sybr Green mix (Molecular Probes). Samples were initially denatured by heating at 95°C for 10 min, followed by a 40-cycle amplification and quantification program (95°C for 15 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s) with a single fluorescence measurement per cycle. The PCR products were between 150 and 200 bp in length. To confirm the amplification of a single PCR product, a melting curve was obtained by slow heating from 60°C to 99.5°C at a rate of 0.5°C every 10 s for 80 cycles, with continuous fluorescence scanning. The results were normalized relative to those obtained for 16S rRNA. Quantification was based on the 2−ΔΔCT method (36).

Transcription initiation site determination.

The rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system version 2.0 (Invitrogen) was used to determine the 5′ ends of rsm transcripts. Total RNA was extracted from P. putida KT2440 cultures at OD600s of 0.8 and 2.8, and the RACE technique was carried out with the oligonucleotides listed in Table 2, following the manufacturer's instructions. Ten clones were sequenced for each transcript, and in all cases, 8 or more gave the same result in terms of identification of the +1 site.

Assays for β-galactosidase activity.

Overnight cultures were diluted 1/100 in fresh LB medium supplemented with 10 μg/ml tetracycline and grown at 30°C for 1 h. Then, the cultures were diluted 1/10 in fresh LB medium and cultivated at 30°C for 1 more hour to allow the reduction of most of the remaining β-galactosidase accumulated in the overnight cultures. Finally, the cultures were diluted to an OD600 of 0.05 in fresh LB medium supplemented with 10 μg/ml tetracycline. The cells were allowed to grow at 30°C, and at the indicated time points, aliquots were taken and β-galactosidase activity was measured as described previously (37). Experiments were carried out in triplicate with two experimental replicates, and all the data represent averages and standard deviations.

Biofilm assays.

Biofilm formation was analyzed in LB medium under static conditions using a microtiter plate assay described previously (38). Alternatively, biofilm development was followed during growth in LB medium in borosilicate glass tubes incubated with orbital rotation at 40 rpm at 30°C. In both cases, the OD600 of the cultures was adjusted to 0.02 or 0.05, respectively, at the start of the experiment. At the indicated times, the liquid was removed and nonadherent cells were washed away by rinsing with distilled water. The biofilms were stained with 1% crystal violet (Sigma) for 15 min, followed by rinsing twice with distilled water. Photographs were taken, and the cell-associated dye was solubilized with 30% acetic acid and quantified by measuring the absorbance at 580 nm (A580). Assays were performed in triplicate.

For confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) analysis of biofilms, cultures were grown in LB medium diluted 1/10 in 24-well glass bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One, Germany). At the indicated times, the biofilms were visualized using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta/AxioVert 200 confocal microscope, and three-dimensional reconstruction was performed with Imaris software (Bitplane).

Motility assays.

Swimming motility was tested on LB plates containing 0.3% (wt/vol) agar. Cells from exponentially growing cultures (2 μl) were inoculated into the plates. Swimming halos were measured after 24 h of inoculation, and the area was calculated. Assays were performed three times with three replicates each. Surface motility assays were done as previously described (39) on plates containing 0.5% (wt/vol) agar.

Statistical methods.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test (set at a P value ≤0.05) or Student's t test for independent samples (P ≤ 0.05), was applied using the R program for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

CsrA/RsmA family proteins and their cognate small RNAs (sRNAs) in P. putida KT2440.

An in silico analysis of the P. putida KT2440 genome indicated that there are three genes in the bacterium encoding CsrA/RsmA family proteins (PP_1746, PP_3832, and PP_4472), which show 46%, 70%, and 75% amino acid identity with CsrA of E. coli, respectively. Alignment of these protein sequences with those of RsmA of P. aeruginosa PAO1 and the three homologs annotated in the genome of P. fluorescens F113 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) led to the following gene nomenclature in KT2440: PP_1746 corresponds to rsmI, PP_3832 to rsmE, and PP_4472 to rsmA. RsmA (62 amino acids) and RsmE (65 amino acids) of P. putida share 54% identical residues, while RsmI (59 amino acids) shows 43% identity with the other two proteins (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). RsmI is also the most divergent in terms of conserved residues that interact with RNA (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). None of the proteins is equivalent to RsmF/RsmN of P. aeruginosa, which are different in structure and sequence from other Rsm proteins, and no homolog of RsmN could be found in P. putida KT2440 based on sequence analysis.

In P. fluorescens, three noncoding sRNAs interact with Rsm proteins: rsmX, rsmY, and rsmZ (17, 18). Previous work had allowed the identification of the sRNAs rsmY and rsmZ in P. putida DOT-T1E (40). Based on sequence homology analysis, we have identified the equivalent sRNAs in KT2440 in the intergenic regions between the loci PP_0370 and PP_0371 (corresponding to rsmY) and between the loci PP_1624 and PP_1625 (corresponding to rsmZ). These sRNAs are 72% and 78% identical to their counterparts in Pseudomonas protegens Pf-5 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The presence or identity of rsmX, on the other hand, is less clear. Based on comparison with the rsmX sequences of P. protegens Pf-5 and P. fluorescens F113, a potential candidate could be located in the intergenic region between PP_0214 and PP_0215 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), but the percent identity was much lower than that of the other two sRNAs (55%).

Generation of rsm single, double, and triple mutants.

We generated rsmI, rsmE, and rsmA null mutants by complete deletion of the open reading frames without introducing antibiotic resistance cassettes, as well as the three double-mutant combinations and the triple mutant (see Materials and Methods for details). For simplicity, here, these mutants are designated ΔI, ΔE, ΔA, ΔIE, ΔEA, ΔIA, and ΔIEA.

The growth of all the mutants was analyzed in liquid cultures in rich and defined minimal media. No differences were observed in LB medium (not shown), whereas in minimal medium, the triple mutant showed an extended lag phase with respect to the wild type, regardless of the carbon source. The same delay was also observed in the ΔEA mutant growing in minimal medium with citrate as a carbon source and, although less pronounced, in the ΔA and ΔEA mutants in minimal medium with glucose as a carbon source (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

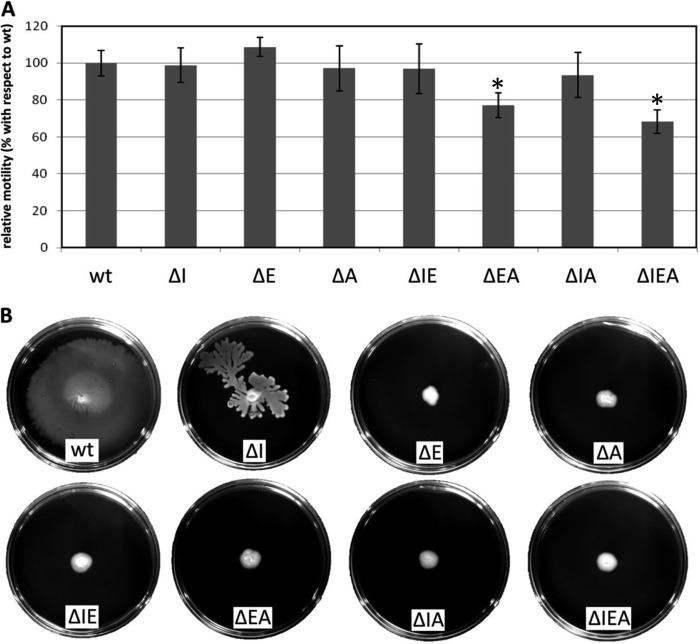

Specific rsm mutations alter the motility of P. putida.

In P. fluorescens F113, it has been reported that mutants affected in the gacS-gacA regulatory system show hypermotility, and a regulatory cascade involving RsmE and RsmI has been proposed (41). This, and the fact that in different bacteria the main target of the response regulator GacA is the RsmA/rsmX-rsmY-rsmZ regulon and that CsrA modulates flagellar genes in E. coli (14), led us to test the influence of rsm mutations on the motility of P. putida KT2440. As shown in Fig. 1A, the triple mutant and the ΔEA strain presented reduced swimming motility with respect to the wild type and the rest of the mutants in LB plates with 0.3% agar.

FIG 1.

Influence of rsm mutations on motility of P. putida. (A) Swimming motility on LB plates with 0.3% agar. The graph indicates the areas covered by swimming halos after overnight growth. The data are the averages and standard deviations of 9 replicates. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (ANOVA; P ≤ 0.05). (B) Surface motility of KT2440 and the rsm single, double, and triple mutants. The images were taken after 48 h of growth and show a representative experiment out of three independent replicates.

The effect of rsm mutations on surface motility was then analyzed on 0.5% agar plates, as previously described (39). Whereas the wild type had nearly covered the surface of the plate after 24 h, none of the mutants showed movement at that time, with the exception of ΔI (Fig. 1B), although that mutant was unable to completely cover the plate surface. This type of motility requires pyoverdine-mediated iron acquisition in KT2440 (39). This prompted us to check if any of the mutants showed altered pyoverdine production that could correlate with the defect in swarming. Pyoverdine was measured in the supernatants of cultures grown overnight in King's B medium (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). All the mutant strains showed a reduction in pyoverdine production with respect to the wild type that could be associated with the observed alteration in swarming motility. However, the difference in motility between ΔI and the remaining mutants cannot be explained simply in terms of pyoverdine production, which was not significantly different between them.

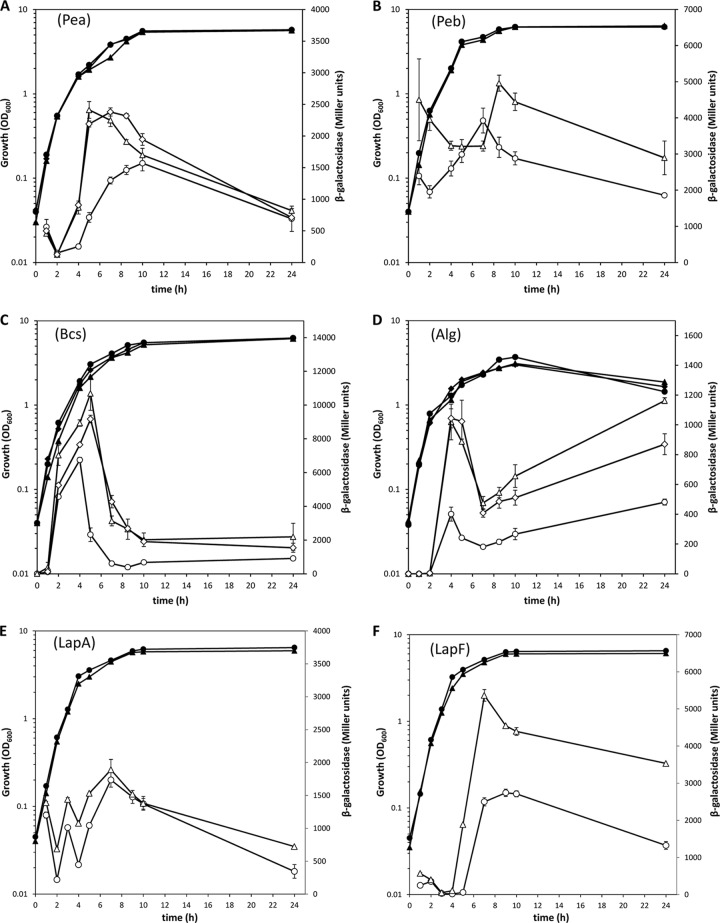

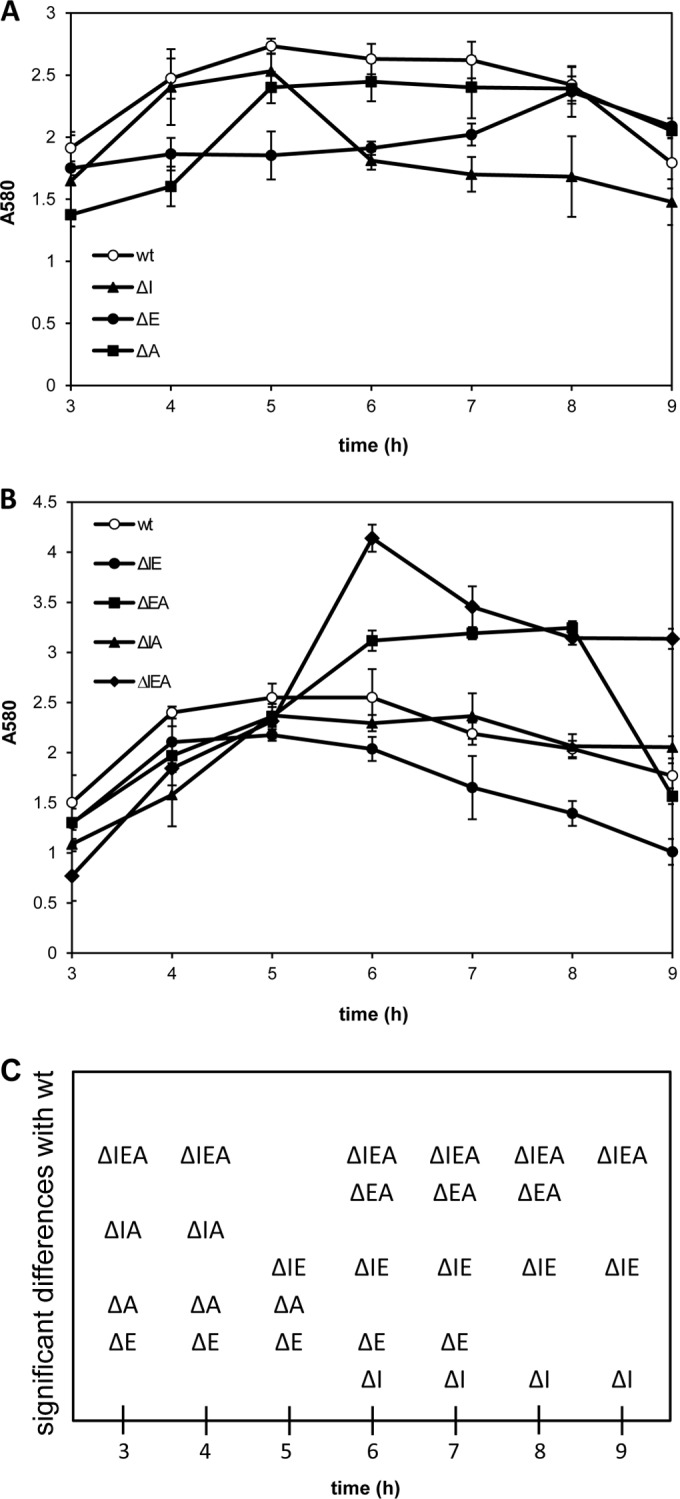

Rsm proteins modulate biofilm development.

Previous results have shown that gacS is involved in the regulation of biofilm formation in P. putida KT2440 (42). We therefore examined the effects of rsm mutations on surface attachment and biofilm development. Assays were first done with cultures grown statically in polystyrene multiwell plates, following the attachment/detachment dynamics over time by staining the surface-associated biomass with crystal violet. As shown in Fig. 2A, each of the rsm single mutants behaved differently in these assays. The ΔI mutant initiated attachment like the wild type but showed early detachment from the surface. The ΔE and ΔA strains, on the other hand, presented reduced attachment during the first hours, reaching attached biomass values similar to those of the wild type at later times. The double and triple mutants were then analyzed (Fig. 2B). In ΔEA and ΔIEA, the attached biomass was significantly above that of the wild type after 6 h, whereas ΔIA and ΔIE kept a kinetic similar to that of the wild type, although the values for the latter were slightly below those of the wild type throughout.

FIG 2.

Biofilm formation by KT2440 and rsm mutant derivatives in polystyrene multiwell plates. Overnight cultures grown in LB medium were diluted to an OD660 of 1, and 5 μl was added to each well containing 200 μl of LB medium. Attachment was followed by removing the liquid from the wells at the indicated times and staining with crystal violet. The data correspond to the measurement of absorbance at 580 nm (A580) after solubilization of the dye and are the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments, each with three replicates per strain. (A) Wild type and single mutants. (B) Wild type, double mutants, and triple mutant. (C) Mutants showing significant differences from the wild type at a given time point (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05).

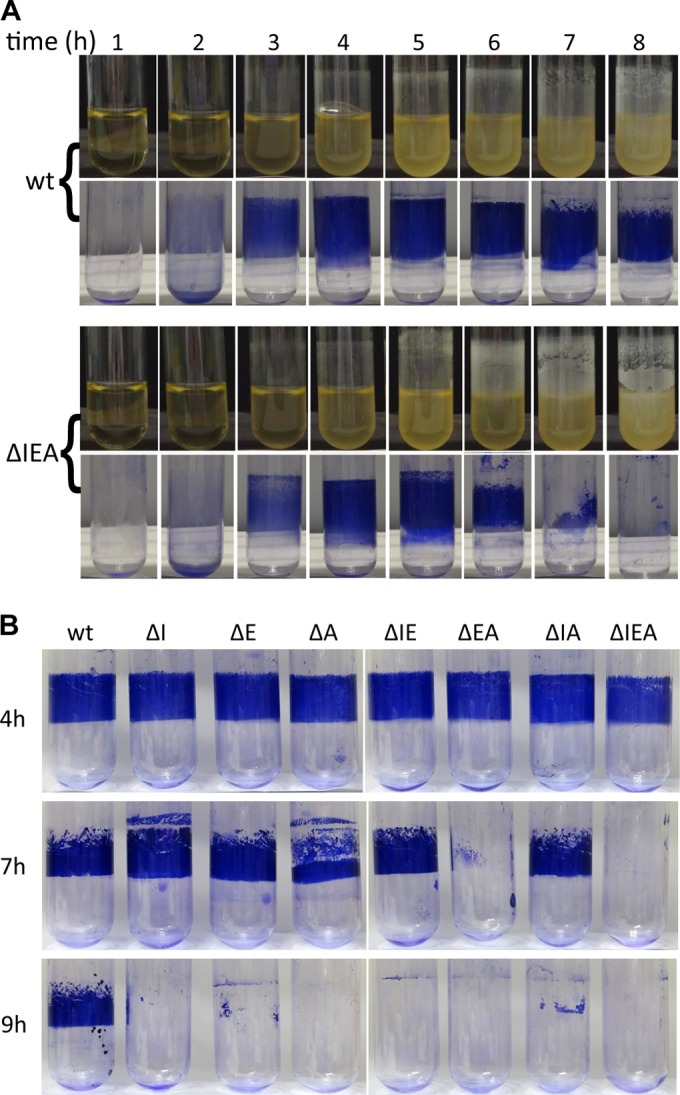

Experiments were also done in borosilicate glass tubes with cultures grown under orbital rotation. We first compared the wild type and the triple mutant over time (Fig. 3A). Observation of the tubes before staining with crystal violet indicated similar attachment dynamics at early time points, with the ΔIEA mutant forming a significantly denser biofilm than the wild type at later time points. However, at these times, the biofilm of the mutant proved to be more labile than that of the wild type, so that it was washed from the surface during staining with crystal violet. A follow-up of this phenomenon in the remaining mutants indicated that ΔEA behaved like the triple mutant and was washed from the surface during staining after 7 h of growth (Fig. 3B). The ΔA mutant was also partly removed at this time, whereas the remaining mutants showed this phenotype at later times, while the biofilm of the wild type remained stainable.

FIG 3.

Kinetics of biofilm formation. (A) Biofilm formation by KT2440 and the rsm triple mutant (ΔIEA) growing in LB medium in borosilicate glass tubes under orbital rotation. At the indicated times, tubes were removed and images (top) were taken before discarding planktonic cells and staining with crystal violet (bottom). (B) Evaluation of the surface-attached biomass in KT2440 and the seven rsm mutants at different times of biofilm development. Growth conditions were as for panel A. Images from a representative experiment out of three replicates are shown (different experiments are represented in panels A and B).

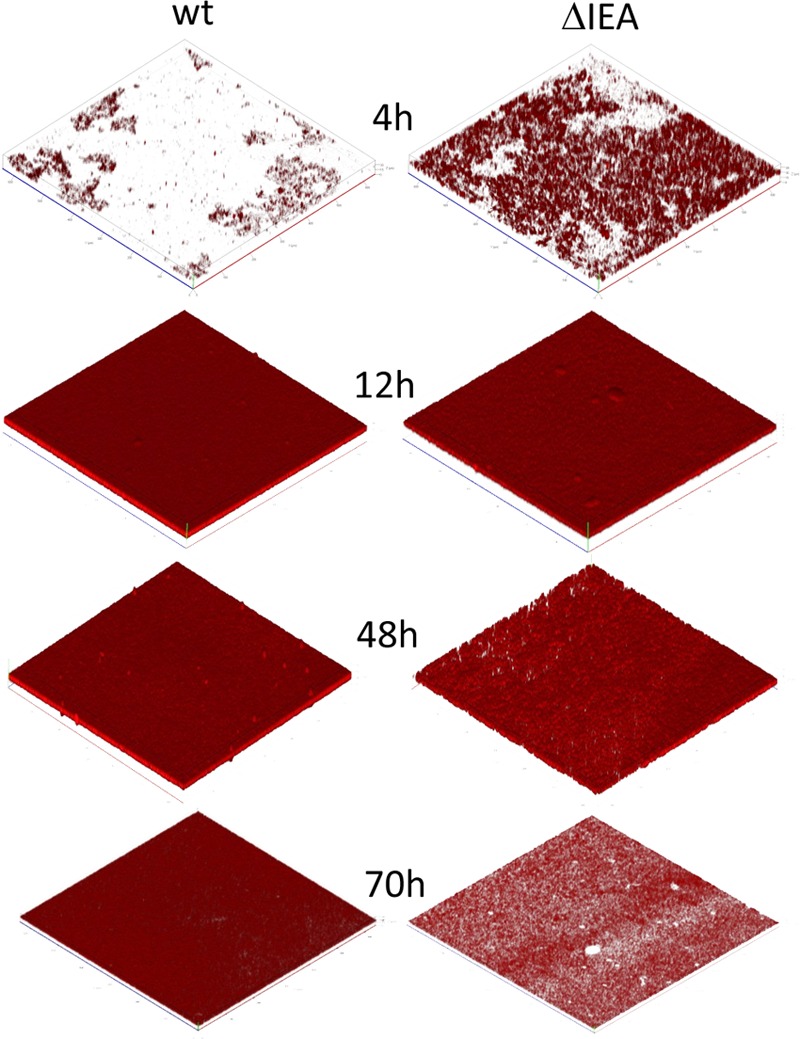

The development of biofilms of KT2440 and the triple mutant tagged with mCherry was also followed in microscopy-ready multiwell plates by CLSM during growth under static conditions. The results presented in Fig. 4 show that under these conditions, ΔIEA started colonizing the surface faster than the wild type and also detached earlier.

FIG 4.

CLSM follow-up of biofilm formation by KT2440 and the rsm triple mutant, ΔIEA. Strains were tagged with miniTn7Ptac-mChe (miniTn7::mCherry) in single copy at an intergenic location in the chromosome. Bacterial cells were grown in LB medium diluted 1:10 in microscopy-ready multiwell plates. Three-dimensional reconstructions, generated with Imaris, of representative fields are shown.

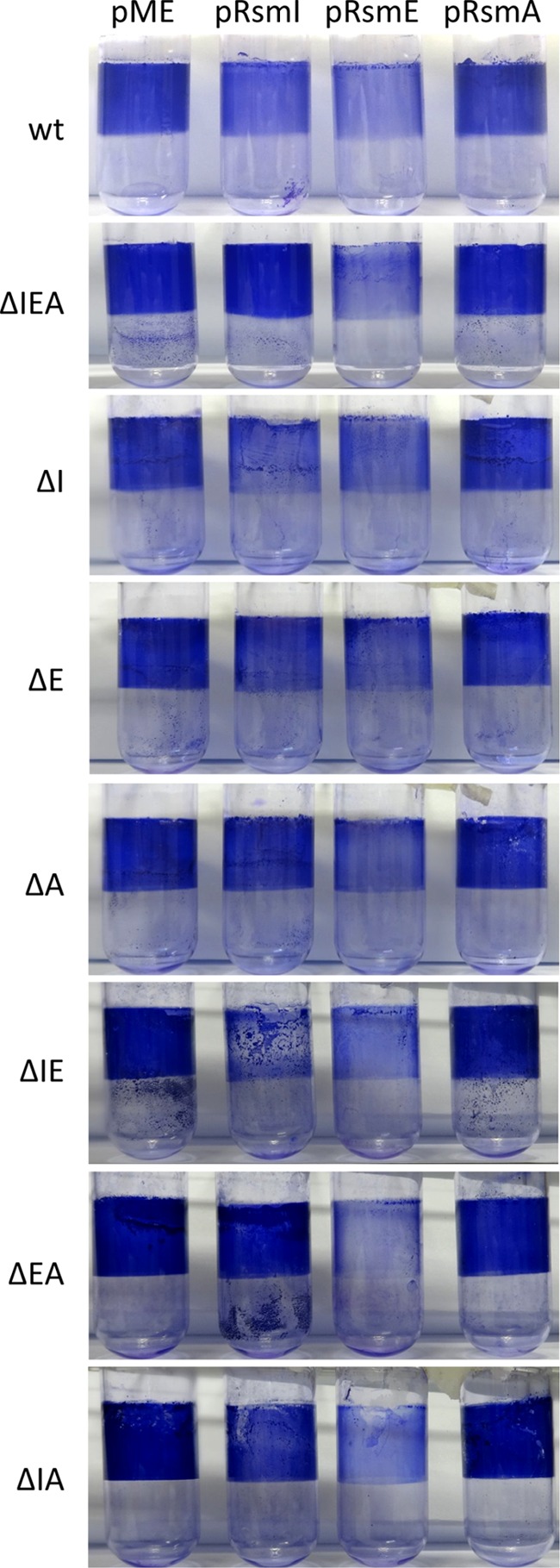

Overexpressing RsmE or RsmI, but not RsmA, causes reduced biofilm formation in KT2440.

To further explore the role of Rsm proteins in biofilm formation, each protein was cloned independently in an expression vector that is stable in Pseudomonas (17) under the control of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). These constructs were introduced into the wild-type KT2440, and biofilm formation was analyzed during growth in LB medium in the presence or absence of IPTG. As shown in Fig. 5, overexpressing RsmE caused a reduction in biofilm formation. The increase in RsmI had a similar, although less pronounced, effect, whereas the increase in RsmA had no obvious influence on biofilm formation. Quantification of the attached biomass after solubilization of the dye revealed 70% and 50% reductions due to overexpression of RsmE and RsmI, respectively (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

Effects of overexpressing each Rsm protein on biofilm formation by KT2440 and the seven rsm mutant derivatives. The genes rsmI, rsmE, and rsmA were cloned in the broad-host-range expression vector pME6032. The resulting constructs (pRsmI, pRsmE, and pRsmA), as well as the empty vector (pME) as a control, were introduced into all the strains. Experiments were done as for Fig. 3. The images show attached biomass stained with crystal violet after 5 h of growth in the presence of 0.1 mM IPTG and 20 μg/ml tetracycline. wt, wild type.

To investigate the potential interplay between the different Rsm proteins, we also introduced each of the expression constructs in all the mutants and analyzed biofilm formation on borosilicate glass tubes (Fig. 5; see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). As with the wild type, overexpression of RsmA had no significant effect regardless of the genetic background, whereas overexpression of RsmE resulted in decreased biofilm formation in all the strains, with small differences between them. Interestingly, the effect observed in the wild type when RsmI was overexpressed was nearly lost in the triple mutant. Analysis of the remaining mutants showed that the presence of intact rsmA was required for the reduced biofilm phenotype associated with RsmI overexpression. It should be noted that at the time at which this analysis was done (5 h after inoculation), the reduction in crystal violet staining was correlated with the visual observation of attached biomass, and it was not a consequence of the biofilm lability that can be observed at later times (shown in Fig. 3).

Influence of Rsm proteins on expression of structural elements of P. putida biofilms.

The results described so far could suggest the possibility that Rsm proteins participate in biofilm formation by altering the surface characteristics of P. putida cells, which would explain why the triple mutant showed thicker but more labile biofilms on glass surfaces while remaining attached on plastic surfaces. This, and the fact that in P. aeruginosa RsmA modulates expression of the Psl exopolysaccharide (7), prompted us to investigate if any of the mutations caused changes in the expression of structural elements known to participate in the buildup of P. putida biofilms under different conditions, namely, the two large adhesins LapA and LapF and the exopolysaccharides Pea, Peb, cellulose (Bcs), and alginate (Alg).

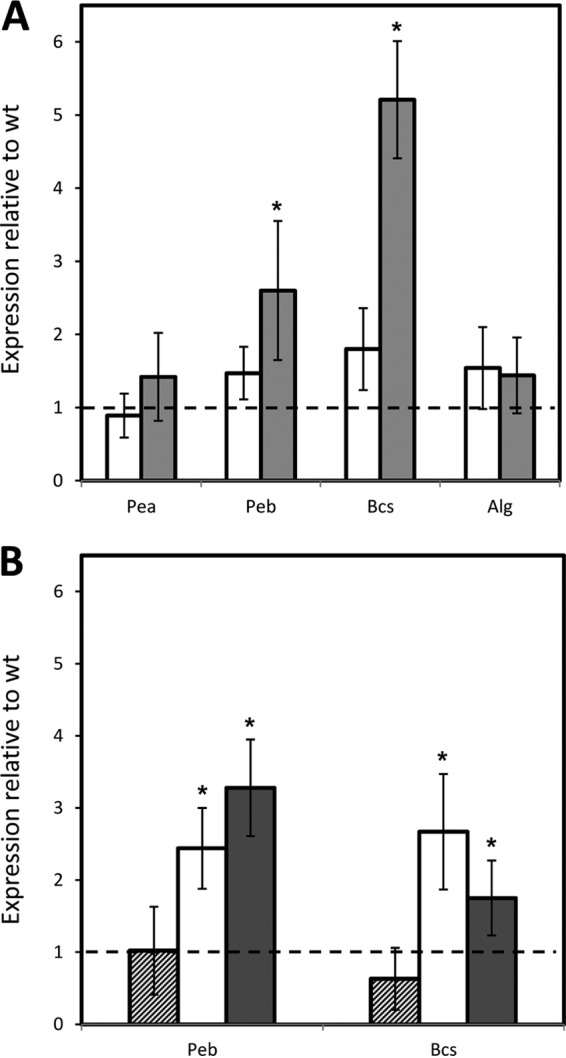

To determine if rsm mutations had an influence on the mRNA levels of genes involved in exopolysaccharide biosynthesis, qRT-PCR was done with RNA extracted from the wild-type and ΔIEA strains grown on solid medium for 24 or 48 h, using primers that correspond to the loci PP_1277 (Alg), PP_1795 (Peb), PP_2629 (Bcs), and PP_3132 (Pea). As shown in Fig. 6A, there was a significant increase in the mRNAs corresponding to Peb (2.5-fold) and Bcs (5-fold) in the triple mutant with respect to the wild type, whereas no significant differences were observed for Pea (PP_3132) and Alg (PP_1277). Analysis of these differences in the single mutants after 48 h indicated that in the case of Peb, the lack of either RsmE or RsmA had an effect similar to that observed in the triple mutant, while RsmI did not appear to influence its expression (Fig. 6B). For Bcs, increased expression was observed in ΔE and ΔA, but in neither case did it reach the levels observed in ΔIEA, suggesting a cumulative effect of both proteins.

FIG 6.

Influence of rsm mutations on mRNA levels of EPS-encoding genes in cultures grown in solid medium. (A) mRNA levels of EPS genes in the rsm triple mutant relative to the wild type analyzed by qRT-PCR. RNA was isolated from samples grown on LB agar plates after 24 h (white bars) or 48 h (gray bars). A value of 1 (dashed line) indicates expression levels identical to those of the wild type. (B) Relative expression of genes corresponding to cellulose (Bcs) and the specific EPS Peb in mutants ΔI (hatched bars), ΔE (gray bars), and ΔA (white bars) with respect to the wild type after 48 h of growth on LB agar plates. The data are the averages and standard deviations from three biological replicates with three technical replicates. The values significantly different from those of the wild type are indicated by asterisks (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05).

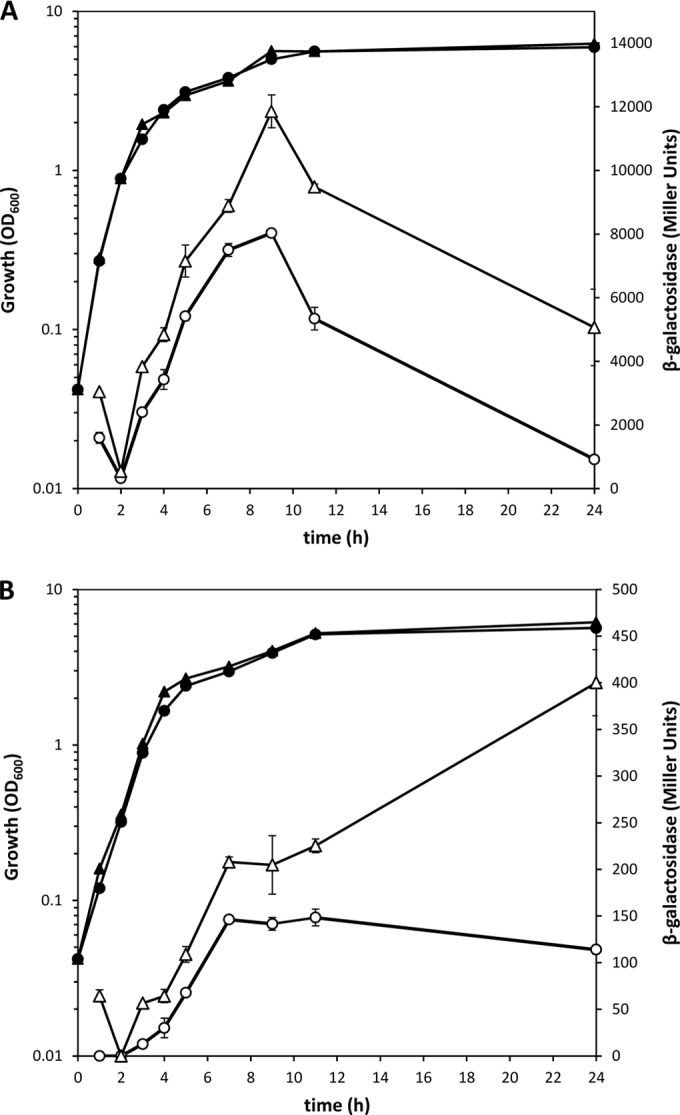

Since Rsm proteins may regulate translation with or without effects on mRNA transcript levels, we decided to expand this analysis by checking the expression patterns of fusions of the first gene in each EPS cluster (including the promoter and first codons) with the reporter gene lacZ devoid of its own promoter, as described elsewhere (51). The results obtained comparing the wild type with the ΔIEA mutant are shown in Fig. 7. In all cases, the pattern of expression showed alterations at different times during growth in liquid medium, with an overall increase in activity in the mutant. In the case of the fusion corresponding to Pea, the differences were significant only between 4 and 8 h of growth, which could explain why qRT-PCR at 24 at 48 h did not reveal alterations in the ΔIEA mutant. Analysis of the fusions in all the mutant backgrounds indicated that in all cases except Peb, the combination of rsmA and rsmE mutations was responsible for most of the observed changes in the triple mutant (Fig. 7A, C, and D), whereas no single or double mutant had the same pattern as ΔIEA in the case of Peb (data not shown).

FIG 7.

Influence of rsm mutations on expression of EPS- and adhesin-encoding genes during growth in liquid medium. Growth (solid symbols) and β-galactosidase activity (open symbols) of KT2440 (circles), ΔIEA (triangles), and ΔEA (diamonds) carrying reporter fusions corresponding to Pea (PP_3132::′lacZ) (A), Peb (PP_1795::′lacZ) (B), Bcs (PP_2629::′lacZ) (C), Alg (algD::′lacZ) (D), lapA::lacZ (E), and lapF::lacZ (F) were followed over time. The data are averages and standard deviations from three biological replicates with two technical repetitions. Statistically significant differences between the wild type and ΔIEA were detected from 4 to 8 h (A); at 2, 4, 8, 10, and 24 h (B); from 2 to 10 h (C); from 4 h onward (D); and from 5 h onward (F) (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05). (D) d-Cycloserine (75 μg/ml) was added after 2 h of growth, since in P. putida, the algD promoter is silent in liquid medium in the absence of cell wall stress (M. I. Ramos-González, unpublished data).

Next, expression of the two adhesins was followed during growth by measuring the β-galactosidase activity of lapA::′lacZ and lapF::′lacZ fusions carried on plasmids pMMGA and pMMG1, respectively (42, 43), in the wild type and all the rsm mutants. No great differences were observed for lapA in the different genetic backgrounds, except for a slight overall increase in ΔIEA (Fig. 7E) that was not significant. In contrast, expression of lapF::lacZ was clearly influenced by the three Rsm proteins, and the triple mutant showed earlier induction and increased β-galactosidase activity with respect to the wild type (Fig. 7F). Detailed analysis in each of the single mutants indicated that the absence of RsmA and RsmE had a cumulative influence on the overall increase in expression, while the lack of RsmI mostly contributed to the earlier peak of activation (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

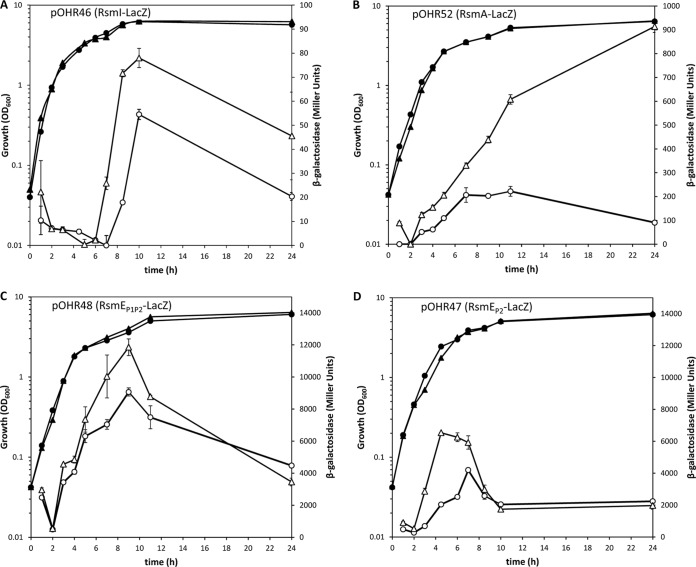

Expression patterns of rsm genes.

RACE was used to determine the transcription initiation sites of the three rsm genes. In rsmI and rsmA, the +1 site was located 63 and 245 bp upstream of the ATG, respectively, while in rsmE, two transcription initiation sites were identified at bases −53 (proximal +1 site) and −183 (distal +1 site) (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The same initiation sites were identified in transcripts from cultures in the exponential or stationary phase of growth.

Based on this information, two translational fusions were constructed with the reporter gene lacZ in plasmid pMP220-BamHI containing the rsmI and rsmA regions upstream of the +1 site (pOHR46 and pOHR52), respectively, and two with rsmE, a fragment containing the proximal +1 site closer to the ATG (pOHR47) and a larger one including both the proximal and distal transcription start sites (pOHR48). All the constructs included the ribosome-binding site and translation initiation codon. The constructs were introduced in KT2440, and β-galactosidase activity was followed during growth in LB medium. The activity of the RsmI-LacZ fusion was very low and was detected only when cultures had already reached the stationary phase (Fig. 8A). The results for RsmA-LacZ (Fig. 8B) showed a gradual increase in activity during exponential growth and the early stationary phase, followed by a decrease later. In the case of RsmE, both constructs showed an increase in expression in midexponential phase (Fig. 8C and D). The difference between the construct harboring the proximal promoter region (P2) and the construct with both promoter regions can be explained if the activity of the distal promoter (P1) is maintained longer than that of P2.

FIG 8.

Expression patterns of Rsm proteins in the wild-type KT2440 and the rsm triple mutant ΔIEA. Growth (solid symbols) and β-galactosidase activity (open symbols) of KT2440 (circles) and ΔIEA (triangles) carrying the different Rsm-LacZ fusions are indicated in each panel. The RsmEP1P2-LacZ fusion contains both distal and proximal promoters, and the RmsEP2-LacZ fusion contains only the proximal promoter. The data are averages and standard deviations from three biological replicates with two technical repetitions. Statistically significant differences between the wild type and ΔIEA were detected from 7 h onward for pOHR46, from 7 h onward for pOHR52, at 7 and 8 h for pOHR48, and from 3 to 7 h for pOHR47 (Student's t test; P < 0.05).

The observations made in different genetic backgrounds with respect to biofilm formation and expression of the extracellular matrix components suggested the existence of cross-regulation between rsm genes. This possibility was first explored by introducing the above-mentioned constructs in the triple mutant. Analysis of β-galactosidase activity showed, in all cases, altered patterns and/or increased levels of expression with respect to the wild type (Fig. 8). The different fusions were then introduced in the single and double mutants. The results obtained with ΔE and ΔA indicated that both RsmE (Fig. 9A) and RsmA (Fig. 9B) have a clear negative effect on their own expression, with the self-repression effect of RsmA during the late stationary phase especially evident (Fig. 9B), while in the remaining combinations of mutations and reporter fusions, the observed changes were minor or nonexistent (data not shown).

FIG 9.

Self-repression exerted by Rsm proteins. Growth (solid symbols) and β-galactosidase activity (open symbols) of KT2440 (circles) and single mutants (triangles) carrying RsmEP1P2-LacZ (ΔE mutant) (A) and RsmA-LacZ (ΔA mutant) (B) fusions. The data are averages and standard deviations from three biological replicates with two technical repetitions. Statistically significant differences between the wild type and the mutant were detected from 3 h onward for RsmEP1P2-LacZ and from 7 h onward for RsmA-LacZ (Student's t test; P ≤ 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The regulatory cascade involving posttranscriptional regulators of the Rsm family and their cognate small RNAs has gained increasing relevance because, beyond its role in secondary metabolism, it is arising as a central element in bacterial gene expression regulation. RsmA homologs are present in diverse bacteria, from generalist species able to adapt to a variety of environments, like P. putida, to highly specialized bacteria with relatively few regulatory proteins, such as the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori, where RsmA controls virulence and the stress response (44). It is noticeable that in the former, which has been the focus of this work, and in related species, such as P. fluorescens or P. protegens, there are three very similar Rsm proteins. Although this could imply the existence of regulatory redundancy or something like a “backup system,” our data suggest that there is a combination of differentiated and cumulative effects attributable to these proteins. This is exemplified by the fact that RsmA and RsmE have roles in swimming motility that can be detected only when both are deleted, whereas the lack of RsmI has no detectable influence on swimming. On the other hand, swarming is completely abolished in all the mutants except ΔI. Other members of the RsmA/CsrA family have been previously described as relevant elements for swarming motility in different bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa (45), Serratia marcescens (46), and Proteus mirabilis (47).

We have shown that Rsm proteins function as negative regulators in the process of biofilm development: the lack of all three proteins causes an increase in biofilm formation, but the robustness of the biofilm in terms of bacterial association with the surface is reduced, resulting in relatively easy and early detachment (Fig. 3 and 4). This effect is observed on glass surfaces, especially with ΔEA and ΔIEA, but it is not evident on plastic, where these strains remain attached to the surface. Under these conditions the single ΔE and ΔA mutants show delayed attachment relative to the wild type, whereas the ΔI mutant presents early detachment.

We have also analyzed the effect of overexpressing each Rsm protein in the wild type and in each mutant background. Our results pinpoint RsmE as the main element modulating bacterial attachment, with RsmI having a less pronounced effect that is dependent on the presence of an intact RsmA, which indicated that there is a regulatory interplay between Rsm proteins, so that they may act in a concerted way on their targets. Expression of the translational fusions constructed in the different genetic backgrounds indicated the existence of self-regulation in rsmA and rsmE and also revealed sequential activation of the different rsm genes. Thus, rsmE and rsmA would be the first to be expressed during growth in rich medium at 30°C, followed by rsmI in stationary phase. Expression of each gene also seems to be turned off sequentially: first rsmA, then rsmE, and finally rsmI. It is also worth mentioning the presence in rsmE of two distinct promoters with different expression dynamics. Although the expression sequence of rsm genes in the same bacterium had not been previously investigated, small RNAs are known to be sequentially expressed. In P. fluorescens (now P. protegens) CHA0, the expression patterns of the three sRNAs that interact with RsmA homologs have been described, with rsmX and rsmY showing a linear increase during growth while rsmZ is expressed at a later time (18). However, a possible correlation with the expression patterns of Rsm proteins has not been studied. It may also be that different environmental conditions cause alterations in the progression of expression of the various elements. Detailed analysis of these aspects will be of great interest in terms of the responses of P. putida to different environmental conditions.

To have a clearer picture of the molecular basis for the role of Rsm proteins in biofilm formation, we have examined their influence on the expression of elements that are required for surface attachment (LapA), cell-cell interactions (LapF), and extracellular matrix composition (both adhesins and EPS). We have shown that the lack of Rsm proteins causes earlier and increased expression of LapF and also increases expression of cellulose and the strain-specific EPS Peb. Previous work has supported the notion that Pea (the other strain-specific EPS) and, to a minor extent, Peb are the exopolysaccharides with the main structural roles in P. putida biofilms grown under conditions similar to those used here, while alginate and cellulose would have a role in different environmental situations (48, 49). Therefore, removing Rsm proteins (particularly RsmE and RsmA) likely promotes cell-cell interactions mediated by LapF, giving rise to thicker biofilms, and causes alterations in the balance and composition of the biofilm extracellular matrix. This probably also has consequences for characteristics such as hydrophobicity, which would explain the lability of the biofilms formed by the triple mutant, despite their increased biomass on glass surfaces, and the differences observed with plastic surfaces. In P. aeruginosa, RsmA negatively influences the expression of psl, one of its two species-specific EPS operons, involved in the architecture of biofilms (7). Similarly, RsmA and RsmE influence the expression of one of the two P. putida-specific EPSs, Peb. However, the modulation of biofilm formation by the Rsm system appears to be far more complex in this bacterium, not only because of the existence of three proteins, but also because of their influence on additional elements involved in surface colonization that are absent in P. aeruginosa (LapF and cellulose).

The results obtained here provide evidence of the regulatory complexities associated with the adaptation of a versatile bacterium like P. putida KT2440 to different environmental conditions. The tools generated in this work (mutants, overexpression constructs, and reporter fusions) and the knowledge gained will be of great importance for further dissection of the elements involved in posttranscriptional control of expression in P. putida.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Cámara and S. Heeb for plasmid pME6032, general advice, and discussion of results. We also acknowledge the comments made by the reviewers, which have helped improve the original manuscript.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and EFDR through grants BFU2010-17946 and BFU2013-43469-P and an FPI predoctoral scholarship (EEBB-BES-2011-047539) to Ó.H.-R.

Funding Statement

This work, including the efforts of Óscar Huertas-Rosales, María Isabel Ramos-González, and Manuel Espinosa-Urgel, was funded by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad and EFDR through grants BFU2010-17946 and BFU2013-43469-P and through a fellowship of the FPI program (EEBB-BES-2011-047539) to Óscar Huertas-Rosales.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01724-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Romeo T, Gong M, Liu MY, Brun-Zinkernagel AM. 1993. Identification and molecular characterization of csrA, a pleiotropic gene from Escherichia coli that affects glycogen biosynthesis, gluconeogenesis, cell size, and surface properties. J Bacteriol 175:4744–4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romeo T. 1998. Global regulation by the small RNA-binding protein CsrA and the non-coding RNA molecule CsrB. Mol Microbiol 29:1321–1330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H, Liu MY, Romeo T. 1996. Coordinate genetic regulation of glycogen catabolism and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli via the csrA gene product. J Bacteriol 178:1012–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabnis NA, Yang H, Romeo T. 1995. Pleiotropic regulation of central carbohydrate metabolism in Escherichia coli via the gene csrA. J Biol Chem 270:29096–29104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pessi G, Haas D. 2001. Dual control of hydrogen cyanide biosynthesis by the global activator GacA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. FEMS Microbiol Lett 200:73–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pessi G, Williams F, Hindle Z, Heurlier K, Holden MTG, Cámara M, Haas D, Williams P. 2001. The global posttranscriptional regulator RsmA modulates production of virulence determinants and N-acylhomoserine lactones in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 183:6676–6683. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6676-6683.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irie Y, Starkey M, Edwards AN, Wozniak DJ, Romeo T, Parsek MR. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix polysaccharide Psl is regulated transcriptionally by RpoS and post-transcriptionally by RsmA. Mol Microbiol 78:158–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colley B, Dederer V, Carnell M, Kjelleberg S, Rice SA, Klebensberger J. 2016. SiaA/D interconnects c-di-GMP and RsmA signaling to coordinate cellular aggregation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to environmental conditions. Front Microbiol 7:179. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu MY, Yang H, Romeo T. 1995. The product of the pleiotropic Escherichia coli gene csrA modulates glycogen biosynthesis via effects on mRNA stability. J Bacteriol 177:2663–2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu MY, Romeo T. 1997. The global regulator CsrA of Escherichia coli is a specific mRNA-binding protein. J Bacteriol 179:4639–4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumer C, Heeb S, Pessi G, Haas D. 1999. Global GacA-steered control of cyanide and exoprotease production in Pseudomonas fluorescens involves specific ribosome binding sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:14073–14078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker CS, Morozov I, Suzuki K, Romeo T, Babitzke P. 2002. CsrA regulates glycogen biosynthesis by preventing translation of glgC in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 44:1599–1610. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pernestig A-K, Georgellis D, Romeo T, Suzuki K, Tomenius H, Normark S, Melefors Ö. 2003. The Escherichia coli BarA-UvrY two-component system is needed for efficient switching between glycolytic and gluconeogenic carbon sources. J Bacteriol 185:843–853. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.843-853.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei BL, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Simecka JW, Prüß BM, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2001. Positive regulation of motility and flhDC expression by the RNA-binding protein CsrA of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 40:245–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weilbacher T, Suzuki K, Dubey AK, Wang X, Gudapaty S, Morozov I, Baker CS, Georgellis D, Babitzke P, Romeo T. 2003. A novel sRNA component of the carbon storage regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 48:657–670. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Cui Y, Mukherjee A, Chatterjee AK. 1998. Characterization of a novel RNA regulator of Erwinia carotovora ssp. carotovora that controls production of extracellular enzymes and secondary metabolites. Mol Microbiol 29:219–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heeb S, Blumer C, Haas D. 2002. Regulatory RNA as mediator in GacA/RsmA-dependent global control of exoproduct formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J Bacteriol 184:1046–1056. doi: 10.1128/jb.184.4.1046-1056.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay E, Dubuis C, Haas D. 2005. Three small RNAs jointly ensure secondary metabolism and biocontrol in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:17136–17141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505673102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heeb S, Haas D. 2001. Regulatory roles of the GacS/GacA two-component system in plant-associated and other Gram-negative bacteria. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:1351–1363. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyytiainen H, Montesano M, Palva ET. 2001. Global regulators ExpA (GacA) and KdgR modulate extracellular enzyme gene expression through the RsmA-rsmB system in Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:931–938. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.8.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reimmann C, Beyeler M, Latifi A, Winteler H, Foglino M, Lazdunski A, Haas D. 1997. The global activator GacA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO positively controls the production of the autoinducer N-butyryl-homoserine lactone and the formation of the virulence factors pyocyanin, cyanide, and lipase. Mol Microbiol 24:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3291701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lapouge K, Schubert M, Allain FH, Haas D. 2008. Gac/Rsm signal transduction pathway of γ-proteobacteria: from RNA recognition to regulation of social behaviour. Mol Microbiol 67:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakazawa T. 2002. Travels of a Pseudomonas, from Japan around the world. Environ Microbiol 4:782–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson K, Weinel C, Paulsen I, Dodson R, Hilbert H, Martins dos Santos V, Fouts D, Gill S, Pop M, Holmes M. 2002. Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the metabolically versatile Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ Microbiol 4:799–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tecon R, Binggeli O, Van der Meer JR. 2009. Double-tagged fluorescent bacterial bioreporter for the study of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon diffusion and bioavailability. Environ Microbiol 11:2271–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lennox ES. 1955. Transduction of linked genetic characters of the host by bacteriophage P1. Virology 1:190–206. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(55)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yousef-Coronado F, Travieso ML, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2008. Different, overlapping mechanisms for colonization of abiotic and plant surfaces by Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol Lett 288:118–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King EO, Ward MK, Raney DE. 1954. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J Lab Clin Met 44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ausubel F, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J, Struhl K. 1987. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enderle PJ, Farwell MA. 1998. Electroporation of freshly plated Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells. Biotechniques 25:954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch B, Jensen LE, Nybroe O. 2001. A panel of Tn7-based vectors for insertion of the gfp marker gene or for delivery of cloned DNA into Gram-negative bacteria at a neutral chromosomal site. J Microbiol Methods 45:187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis KN. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol 172:6557–6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis GR. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matilla MA, Travieso ML, Ramos JL, Ramos-González MI. 2011. Cyclic diguanylate turnover mediated by the sole GGDEF/EAL response regulator in Pseudomonas putida: its role in the rhizosphere and an analysis of its target processes. Environ Microbiol 13:1745–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Toole GA, Kolter R. 1998. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 28:449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matilla MA, Ramos JL, Duque E, Alché JD, Espinosa-Urgel M, Ramos-González MI. 2007. Temperature and pyoverdine-mediated iron acquisition control surface motility of Pseudomonas putida. Environ Microbiol 9:1842–1850. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Molina-Santiago C, Daddaoua A, Gómez-Lázaro M, Udaondo Z, Molin S, Ramos JL. 2015. Differential transcriptional response to antibiotics by Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. Environ Microbiol 17:3251–3262. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez-Granero F, Navazo A, Barahona E, Redondo-Nieto M, Rivilla R, Martín M. 2012. The Gac-Rsm and SadB signal transduction pathways converge on AlgU to downregulate motility in Pseudomonas fluorescens. PLoS One 7:e31765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martínez-Gil M, Ramos-González MI, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2014. Roles of cyclic di-GMP and the Gac system in transcriptional control of the genes coding for the Pseudomonas putida adhesins LapA and LapF. J Bacteriol 196:1287–1313. doi: 10.1128/JB.01287-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez-Gil M, Yousef-Coronado F, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2010. LapF, the second largest Pseudomonas putida protein, contributes to plant root colonization and determines biofilm architecture. Mol Microbiol 77:549–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnard FM, Loughlin MF, Fainberg HP, Messenger MP, Ussery DW, Williams P, Jenks PJ. 2004. Global regulation of virulence and the stress response by CsrA in the highly adapted human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol 51:15–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heurlier K, Williams F, Heeb S, Dormond C, Pessi G, Singer D, Cámara M, Williams P, Haas D. 2004. Positive control of swarming, rhamnolipid synthesis, and lipase production by the posttranscriptional RsmA/RsmZ system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J Bacteriol 186:2936–2945. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.10.2936-2945.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ang S, Horng YT, Shu JC, Soo PC, Liu JH, Yi WC, Lai HC, Luh KT, Ho SW, Swift S. 2001. The role of RsmA in the regulation of swarming motility in Serratia marcescens. J Biomed Sci 8:160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liaw SJ, Lai HC, Ho SW, Luh KT, Wang WB. 2003. Role of RsmA in the regulation of swarming motility and virulence factor expression in Proteus mirabilis. J Med Microbiol 52:19–28. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen L, Li X, Halverson LJ. 2011. Cell-cell and cell-surface interactions mediated by cellulose and a novel exopolysaccharide contribute to Pseudomonas putida biofilm formation and fitness under water-limiting conditions. Environ Microbiol 13:1342–1356. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nilsson M, Chiang WC, Fazli M, Gjermansen M, Givskov M, Tolker-Nielsen T. 2011. Influence of putative exopolysaccharide genes on Pseudomonas putida KT2440 biofilm stability. Environ Microbiol 13:1357–1369. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodcock DM, Crowther PJ, Doherty J, Jefferson S, DeCruz E, Noyer-Weidner M, Smith SS, Michael MZ, Graham MW. 1989. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res 17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molina-Henares MA, Ramos-González MI, Daddaoua A, Fernández-Escamilla AM, Espinosa-Urgel M. 2016. FleQ of Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is a multimeric cyclic diguanylate binding protein that differentially regulates expression of biofilm matrix components. Res Microbiol, in press. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.