Abstract

Vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG) produces high rates of type 2 diabetes remission; however, the mechanisms responsible for this remain incompletely defined. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is a gut hormone that contributes to the maintenance of glucose homeostasis and is elevated after VSG. VSG-induced increases in postprandial GLP-1 secretion have been proposed to contribute to the glucoregulatory benefits of VSG; however, previous work has been equivocal. In order to test the contribution of enhanced β-cell GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) signaling we used a β-cell-specific tamoxifen-inducible GLP-1R knockout mouse model. Male β-cell-specific Glp-1rβ-cell+/+ wild type (WT) and Glp-1rβ-cell−/− knockout (KO) littermates were placed on a high-fat diet for 6 weeks and then switched to high-fat diet supplemented with tamoxifen for the rest of the study. Mice underwent sham or VSG surgery after 2 weeks of tamoxifen diet and were fed ad libitum postoperatively. Mice underwent oral glucose tolerance testing at 3 weeks and were euthanized at 6 weeks after surgery. VSG reduced body weight and food intake independent of genotype. However, glucose tolerance was only improved in VSG WT compared with sham WT, whereas VSG KO had impaired glucose tolerance relative to VSG WT. Augmentation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion during the oral glucose tolerance test was blunted in VSG KO compared with VSG WT. Therefore, our data suggest that enhanced β-cell GLP-1R signaling contributes to improved glucose regulation after VSG by promoting increased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Bariatric surgery, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG), is currently the most effective long-term treatment for obesity and results in high rates of type 2 diabetes remission, often before body weight loss (1, 2). However, the mechanisms by which this occurs are not well defined. VSG has gained interest as a low morbidity bariatric surgery, which is effective in producing weight loss and improving glucose regulation (3). VSG involves removal of approximately 70% of the stomach by transecting along the greater curvature of the stomach. Similar to RYGB, VSG produces diabetes remission and improves glucose homeostasis in both rodent and human clinical studies, making this procedure increasingly popular (3, 4).

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) is an incretin hormone secreted from intestinal enteroendocrine L-cells in response to nutrient ingestion. As an incretin hormone, GLP-1 acts to enhance glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) (5). Other actions of GLP-1 include enhancing insulin sensitivity, inhibiting glucagon secretion, and decreasing appetite (5). Once secreted, active GLP-1 is rapidly degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase-IV and has a half-life of approximately 2 minutes in the circulation. GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitors improve glucose homeostasis, GSIS, and insulin sensitivity, making them effective therapeutics for patients with type 2 diabetes (6, 7).

Postprandial GLP-1 secretion is elevated after several types of bariatric surgery, including VSG and RYGB surgery, which has been suggested to play an important role in mediating the metabolic benefits of these procedures (3, 8, 9). Surprisingly, work in whole-body GLP-1R knockout mice conclude that GLP-1R does not contribute to the glucoregulatory benefits of bariatric surgery (10). However, these experiments used noninducible knockout models, which pose the limitation of potential development of compensatory pathways. Also, whole-body knockouts do not allow tissue-specific observations. In order to test the contributions of β-cell GLP-1R signaling without potential confounding by the presence of compensatory pathways, we used a β-cell-specific inducible GLP-1R knockout mouse model. This is the first study to use an inducible GLP-1R knockout mouse model and investigate the β-cell-specific contribution of GLP-1R signaling to the glucoregulatory benefits of any type of bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

Diets and animals

Tamoxifen-inducible β-cell-specific GLP-1R knockout mice (MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r) were developed by crossing humanized Glp-1r knock-in mice (11) with MIP-Cre/ERT mice (12), both of which are on a C57BL/6 background. Importantly, Glp-1r knock-in mice express the human ortholog from the murine Glp-1r locus, which contains flanking LoxP sites that enable Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of the receptor, as previously validated (11). The MIP-Cre/ERT model (Tg(Ins1-cre/ERT)1Lphi) uses a fragment of the mouse Ins1 promoter to drive expression of the tamoxifen-inducible Cre/ERT (12). This Cre line was chosen because it achieves high expression in pancreatic β-cells but is not expressed in the brain.

Tamoxifen-inducible β-cell-specific GLP-1R knockout was achieved by feeding a 45% high-fat diet with 400-mg/kg diet tamoxifen citrate (Teklad Custom Diet, 06415) or by sc injections of 2 mg/g of tamoxifen (T5648; Sigma). At 2 months of age, male Glp-1rβ-cell+/+ (WT) and Glp-1rβ-cell−/− (KO) littermates were placed on a high-fat diet in order to produce an obese and insulin resistant phenotype, as previously described (13). At 3.5 months of age, mice were switched to a high-fat diet with 400-mg/kg diet tamoxifen citrate (Teklad Custom Diet, 06415) for 2 weeks in order to produce knockdown of the GLP-1R before surgery. At 4 months of age, mice underwent sham or VSG surgery. The following groups were studied: sham-operated Glp-1rβ-cell+/+ (sham WT), sham-operated Glp-1rβ-cell−/− (sham KO), VSG-operated Glp-1rβ-cell+/+ (VSG WT), and VSG-operated Glp-1rβ-cell−/− (VSG KO) (sham WT: n = 9, sham KO: n = 9, VSG WT: n = 7, VSG KO: n = 8). Pre- and postoperative care and VSG and sham surgeries were performed as previously described (13). Mice were maintained on tamoxifen citrate high-fat diet throughout the study ad libitum. Food intake and body weight were measured twice per week. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed at 3 weeks after surgery, after a 6-hour fast (1-g/kg body weight gavage with dextrose), as previously described (13). Oral glucose tolerance test glucose measurements were made using a glucometer (One-Touch Ultra; Lifescan). Serum GLP-1 concentrations were measured by sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery). Serum insulin concentrations were measured by ELISA (Millipore). Overnight (12 h) fasted mice were euthanized 1.5 months after surgery by an overdose of pentobarbital (200 mg/kg ip). The experimental protocols were approved by the Cornell University and Eli Lilly and Company Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

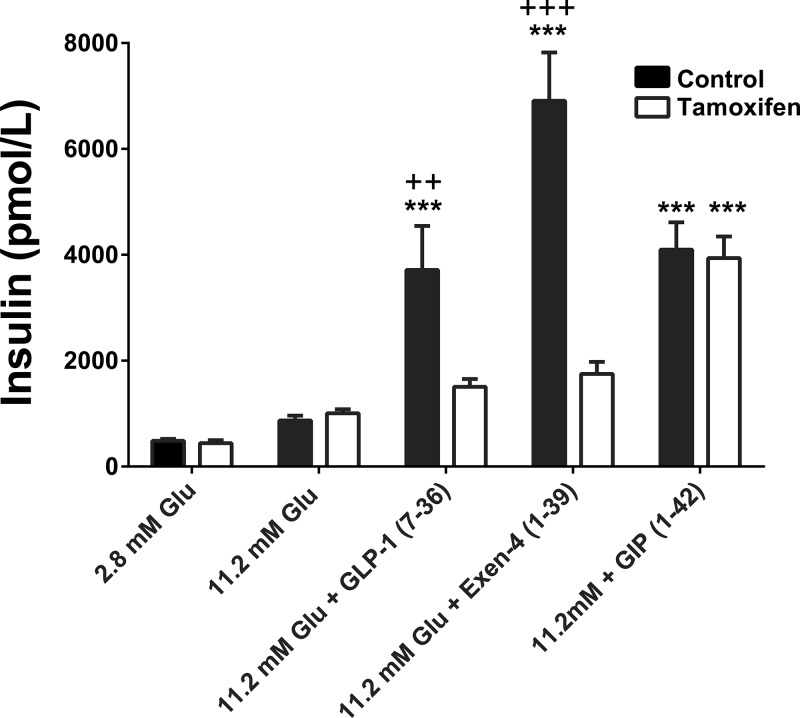

Pancreatic islet isolation and assessment of GSIS

In order to assess knockdown of β-cell GLP-1R, islets were harvested from Cre+ MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r mice with and without tamoxifen treatment. Mouse islets were harvested after collagenase digestion and purified using a Histopaque gradient, as previously described (11). GSIS was assessed under the following conditions: 2.8mM glucose, 11.2mM glucose, 11.2mM glucose + 30nM GLP-1 (7–36), 11.2mM glucose + 30nM exendin-4 (Exen-4) (1–39) or 11.2mM glucose + 30nM glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) (1–42) and assayed for insulin by sandwich electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery).

Statistics and data analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software). Data were analyzed by ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test or by Student's t test as indicated. Differences were considered significant at P < .05.

Results

Validation of tamoxifen-inducible β-cell-specific GLP-1R knockdown

In order to assess knockdown of β-cell GLP-1R, a series of experiments were conducted in islets isolated from Cre+ MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r mice with and without tamoxifen treatment. As expected, islets isolated from nontamoxifen treated mice exhibited increased GSIS in response to incubation with 11.2mM glucose plus 30nM GLP-1, GIP, or Exen-4 compared with 11.2mM glucose alone (P < .0001) (Figure 1). In contrast, islets isolated from tamoxifen-treated mice did not exhibit an augmentation in GSIS in response to incubation with 11.2mM glucose plus GLP-1 or Exen-4 compared with 11.2mM glucose alone. Furthermore, islets isolated from tamoxifen-treated mice exhibited lower GSIS in response to 11.2mM glucose plus 30nM GLP-1 or Exen-4 compared with islets from nontamoxifen treated mice (P < .001) (Figure 1). Islets from tamoxifen-treated mice exhibited similar increases in GSIS in response to incubation with 11.2mM glucose plus GIP compared with islets from nontamoxifen treated Cre+ MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r mice, confirming that GIP receptor function remains intact (Figure 1). Overall, these findings demonstrate β-cell-specific tamoxifen-inducible knockdown of GLP-1R signaling in the MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r mouse model.

Figure 1.

Validation of tamoxifen-inducible β-cell-specific GLP-1R knockdown. Pancreatic islets isolated from Cre+ MIP-Cre-hGlp-1r mice with and without tamoxifen treatment were incubated with 2.8mM glucose, 11.2mM glucose, 11.2mM glucose + 30nM GLP-1, 11.2mM glucose + 30nM Exen-4 or 11.2mM glucose + 30nM GIP, and insulin secretion was measured; ***P < .0001 vs 11.2mM glucose control; +++P < .0001 control vs tamoxifen; ++P < .001 control vs tamoxifen by one-factor ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test. Control = Glp-1rβ-cell+/+, tamoxifen = Glp-1rβ-cell−/−.

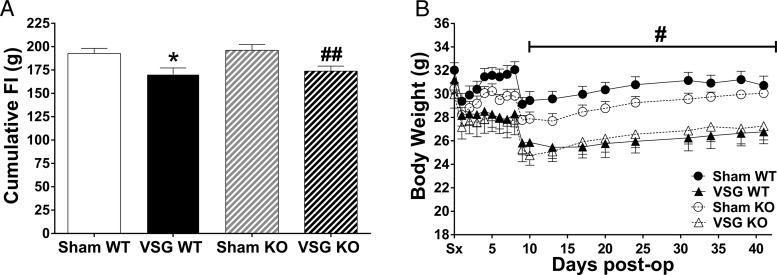

VSG surgery decreases food intake and body weight independent of β-cell GLP-1R

Body weight and food intake were reduced in VSG-operated Glp-1rβ-cell+/+ (VSG WT) and VSG-operated Glp-1rβ-cell−/− (VSG KO) compared with their respective sham-operated controls (sham WT and sham KO) (P < .05) (Figure 2, A and B). Body weight did not differ between genotype for the 2 different treatment conditions. Therefore, we were able to assess the body weight-independent contribution of β-cell GLP-1R to the glucoregulatory benefits of VSG.

Figure 2.

Pancreatic β-cell GLP-1R does not contribute to VSG-induced reductions in food intake and body weight. Cumulative food intake (A) and body weight (B); *P < .05 VSG WT vs sham WT; ##P < .05 VSG KO vs sham KO; #P < .05 VSG vs sham by Student's t test. Wild type (WT) = Glp-1rβ-cell+/+; knockout (KO) = Glp-1rβ-cell−/−.

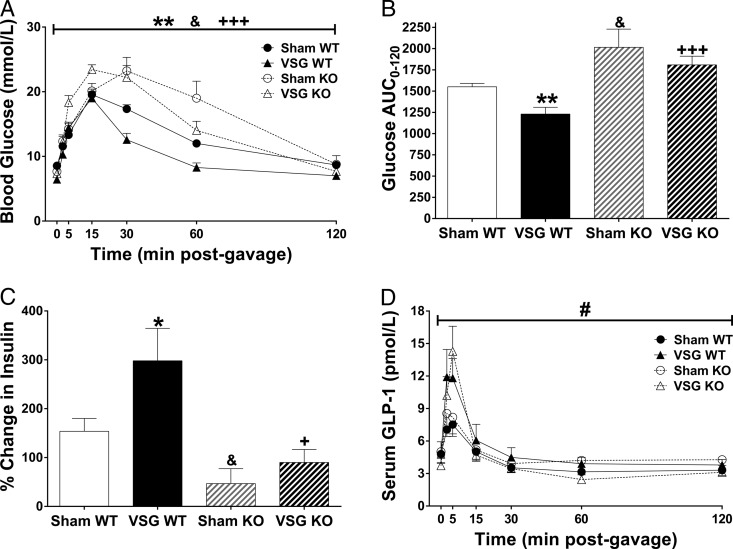

β-Cell GLP-1R contributes to improved glucose tolerance by promoting increased GSIS after VSG

At 3 weeks after surgery, glucose tolerance was improved in VSG WT, but not VSG KO, compared with sham-operated groups (P < .05) (Figure 3A). Furthermore, the glucose area under the curve (AUC) during the oral glucose tolerance test was significantly elevated in VSG KO compared with VSG WT, demonstrating that the β-cell GLP-1R contributes to improved glucose tolerance after VSG (P < .05) (Figure 3B). Although we see a significant increase in glucose AUC in sham KO compared with sham WT (P < .05) (Figure 3B), VSG in KO animals still failed to improve glucose tolerance compared with sham KO. This demonstrates β-cell GLP-1R is necessary for improvements of glucose tolerance after VSG. The percent increase in insulin from baseline to 15 minutes after the glucose gavage was increased in VSG WT compared with sham WT. This effect was lost in VSG KO compared with sham KO, demonstrating that the β-cell GLP-1R contributes to improved insulin secretion after VSG. Furthermore, insulin secretion was lower in VSG KO compared with VSG WT (P < .05) (Figure 3C). GLP-1 secretion did not differ between genotype for either treatment condition (Figure 3D). As expected, GLP-1 secretion increased independently of genotype in VSG groups compared with their respective sham groups (P < .05) (Figure 3D). Interestingly, glucose excursions were elevated and insulin secretion was decreased in sham KO compared with sham WT, demonstrating that the β-cell GLP-1R contributes to maintenance of glucose homeostasis and GSIS under high-fat diet conditions. Together, these data demonstrate that the β-cell GLP-1R contributes to improved glucose tolerance after VSG by enhancing GSIS.

Figure 3.

Pancreatic β-cell GLP-1R contributes to improved glucose tolerance by promoting increased GSIS after VSG. Blood glucose concentrations (A), glucose AUC (B), percent increase in serum insulin concentrations from baseline to 15 minutes after glucose gavage (C), and serum total GLP-1 concentrations during an oral glucose tolerance test (D); *P < .05; **P < .01 VSG WT vs sham WT; +P < .05; +++P < .01 VSG KO vs VSG WT; & P < .05 sham KO vs sham WT; #P < .05 VSG vs sham by Student's t test. Wild type (WT) = Glp-1rβ-cell+/+; knockout (KO) = Glp-1rβ-cell−/−.

Discussion

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that β-cell GLP-1R signaling contributes to the effect of VSG to improve glucose tolerance and increase GSIS. Our data suggest that β-cell GLP-1R signaling does not contribute to the effect of VSG to reduce body weight or food intake. However, a lack of β-cell GLP-1R signaling attenuated improvements in glucose tolerance and GSIS after VSG. Our findings are consistent with data in human patients, reporting a blunting in GSIS after bariatric surgery with acute exposure to the GLP-1R antagonist Exen-4(9–39) (14, 15). Overall, our study suggests that the β-cell GLP-1R contributes to improved glucose homeostasis after VSG by improving islet function.

Postprandial GLP-1 secretion has been shown to increase after various types of bariatric surgeries, in both human and rodent studies (3, 8). Therefore, GLP-1 has been suggested to contribute to improvements in glucose homeostasis after bariatric surgery. Surprisingly, previous studies in whole-body GLP-1R knockout mice report that VSG produces similar improvements in glucose regulation in Glp-1r+/+ and Glp-1r−/− mice (10, 16). However, these studies may have been confounded by development of adaptations and/or redundant pathways. Therefore, our inducible β-cell-specific GLP-1R knockout mouse model allowed us to address this confounding issue and assess the specific role of pancreatic β-cell GLP-1R signaling in VSG-induced improvements in glucose regulation.

In addition to studies conducted in whole-body GLP-1R knockout mouse models, other studies have investigated the role of the GLP-1R in improved metabolism after bariatric surgery using a GLP-1R antagonist. One previous study reported no difference in body weight after RYGB in rats with and without treatment with the GLP-1R antagonist, Exen-4(9–39) (17). This is in line with our data showing that pancreatic β-cell GLP-1R does not contribute to body weight loss after VSG. A recent study compared intracerebroventricular with peripheral delivery of Exen-4(9–39) in a murine model of RYGB. In support of a role for the β-cell GLP-1R, their results suggest that peripheral, but not central, GLP-1R signaling contributes to improved glucose tolerance after RYGB (18). Although the use of Exen-4(9–39) has contributed to our understanding of the role of the GLP-1R in the glucoregulatory benefits of bariatric surgery, the use of Exen-4(9–39) does not allow for tissue-specific observations.

GLP-1 has been reported to exert its incretin action through β-cell GLP-1R and through central nervous system GLP-1R signaling (19–21). Our work demonstrates that β-cell GLP-1R signaling contributes to the effect of VSG to enhance GSIS. Our data, in conjugation with previous work reporting that intracerebroventricular administration of Exen-4(9–39) does not affect glucoregulatory outcomes after RYGB (18), suggest that central nervous system GLP-1R signaling does not contribute to postoperative enhancement in GSIS. Ideally, this would be confirmed in a neuron-specific inducible knockout mouse model. In conclusion, this study provides novel data on the contribution of enhanced postprandial GLP-1 secretion after VSG to postoperative improvements in glucose regulation. Importantly, our data suggest that β-cell GLP-1R signaling contributes to improved glucose regulation after VSG by enhancing islet function.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by startup support from Cornell University and The State University of New York Graduate Diversity Fellowship. B.P.C.'s laboratory also received funding during the project period from the Cornell Comparative Cancer Biology Training Program, the President's Council of Cornell Women, Eli Lilly and Company, and the National Institutes of Health Grant R21CA195002–01A1.

Disclosure Summary: B.P.C.'s laboratory receives funding from Eli Lilly and Company and A.L.C., J.V.F., M.D.M., and K.W.S. are employed by Eli Lilly and Company. D.G., A.K.M., and S.A.L. have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Exen-4

- exendin-4

- GIP

- glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP-1

- glucagon-like peptide-1

- GLP-1R

- GLP-1 receptor

- GSIS

- glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- KO

- knockout

- OGTT

- glucose tolerance test

- RYGB

- Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- VSG

- vertical sleeve gastrectomy

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222(3):339–350; discussion 350–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen B, Peters T, et al. Improvement in glucose metabolism after bariatric surgery: comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abbatini F, Rizzello M, Casella G, et al. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding on type 2 diabetes. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(5):1005–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3(3):153–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet. 2009;374(9683):39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Muscelli E, Casolaro A, Gastaldelli A, et al. Mechanisms for the antihyperglycemic effect of sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2818–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chambers AP, Jessen L, Ryan KK, et al. Weight-independent changes in blood glucose homeostasis after gastric bypass or vertical sleeve gastrectomy in rats. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(3):950–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cummings DE, Overduin J, Shannon MH, Foster-Schubert KE. Hormonal mechanisms of weight loss and diabetes resolution after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(3):358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wilson-Pérez HE, Chambers AP, Ryan KK, et al. Vertical sleeve gastrectomy is effective in two genetic mouse models of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor deficiency. Diabetes. 2013;62(7):2380–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jun LS, Showalter AD, Ali N, et al. A novel humanized GLP-1 receptor model enables both affinity purification and Cre-LoxP deletion of the receptor. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wicksteed B, Brissova M, Yan W, et al. Conditional gene targeting in mouse pancreatic β-cells: analysis of ectopic Cre transgene expression in the brain. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3090–3098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGavigan AK, Garibay D, Henseler ZM, et al. TGR5 contributes to glucoregulatory improvements after vertical sleeve gastrectomy in mice. Gut. 2015;0:1–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jørgensen NB, Dirksen C, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Exaggerated glucagon-like peptide 1 response is important for improved β-cell function and glucose tolerance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3044–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salehi M, Gastaldelli A, D'Alessio DA. Blockade of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor corrects postprandial hypoglycemia after gastric bypass. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):669–680.e662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mokadem M, Zechner JF, Margolskee RF, Drucker DJ, Aguirre V. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on energy and glucose homeostasis are preserved in two mouse models of functional glucagon-like peptide-1 deficiency. Mol Metab. 2014;3(2):191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ye J, Hao Z, Mumphrey MB, et al. GLP-1 receptor signaling is not required for reduced body weight after RYGB in rodents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;306(5):R352–R362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carmody JS, Muñoz R, Yin H, Kaplan LM. Peripheral, but not central, GLP-1 receptor signaling is required for improvement in glucose tolerance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;310(10):E855–E861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knauf C, Cani PD, Perrin C, et al. Brain glucagon-like peptide-1 increases insulin secretion and muscle insulin resistance to favor hepatic glycogen storage. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3554–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Burmeister MA, Ferre T, Ayala JE, King EM, Holt RM, Ayala JE. Acute activation of central GLP-1 receptors enhances hepatic insulin action and insulin secretion in high-fat-fed, insulin resistant mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302(3):E334–E343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamont BJ, Li Y, Kwan E, Brown TJ, Gaisano H, Drucker DJ. Pancreatic GLP-1 receptor activation is sufficient for incretin control of glucose metabolism in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):388–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]