Abstract

Aim:

We aimed to measure the perceived stigma, especially in patients with alopecia areata (AA) and to compare the results with patients with mental disorder (MD).

Materials and Methods:

This study included forty patients with AA who were consecutively recruited from dermatology outpatient clinic and 42 patients with MD who were consecutively recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinic. The presence of a MD was assessed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder Fourth Edition. All participants were asked to complete the 28 items modified stigmatization questionnaire.

Results:

Total and all subscale scores of stigmatization questionnaire scale were higher in the group of patients with AA than in the patients with MD.

Conclusion:

AA is a condition that leads to more self-stigmatization than MD.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, mental disorder, perceived stigma

INTRODUCTION

Physical appearance and attraction is an attached particular importance in today's social structure. That is why problems of hair, which plays a prominent role in the physical attraction, may create significant psychological and social issues for people.[1] Stigmatization is the state of being isolated, marginalized, and ignored by the general population because of a disease or degrading sign the person has.[2] Hair diseases act as a stigma when they cause notable changes in the physical appearance. Therefore, stigmatization becomes an important psychological issue in patients with hair diseases. There are a number of studies in the literature investigating stigmatization, especially caused by psoriasis;[3,4,5,6] however, there is only a limited number of studies investigating the feeling of stigmatization in patients with various chronic skin diseases, which may also cause stigmatization.[7,8]

Alopecia areata (AA) is a benign inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by the loss of hair without scars, which is prevalent in 0.1% of the population.[9] Severity, pattern, and duration of the disease vary extremely from a single small alopecic plaque, which can be hidden easily to complete loss of eyebrows, eyelashes, or hair. Although it is not life-threatening and creates no significant pain, ache, or itch, it has been associated with notable emotional stress and low self-esteem.[10,11] Such negative thoughts may also lead to significant reduction in the quality of life. Many previous studies have described significant feeling of stigmatization in patients with mental disorders (MD).[12,13] Thus, we hypothesized that AA may contribute to a similar degree of perceived stigma. In this study, we aimed to measure the perceived stigma especially in patients with AA; and to compare the results with patients with MD. We also evaluated the demographic and clinical factors related to the perceived stigma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

Patients with AA who presented to Afyon Kocatepe University Hospital outpatient clinic of dermatology in winter and spring 2013, were included in this cross-sectional study. Patients with MD were consecutively recruited from psychiatric outpatient clinic. The presence of a MD was assessed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).[14] Patients were included in the study if they had at least one of the following diagnoses: psychotic disorder, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, sleep disorder, or somatoform disorder. Patients had been diagnosis with MD at least 6 months prior to inclusion to the study. All patients with MD were using psychotropic drug. Exclusion criteria for patients with MD: (i) Age <18 years or 65> (ii) any significant medical illness (iii) any comorbid DSM-IV-Text Revision Axis II diagnosis (personality disorders) (iv) severe cognitive impairment and lack of insight that might influence the interview and study results. The study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee, and all the patients signed an informed consent form before recruitment. Exclusion criteria for patients with AA: (i) Any visible skin diseases or scars other than AA (ii) patients having only body hair loss (iii) any previous diagnosis of a psychiatric disorders (iv) age <16. Patients’ demographic data such as age, gender, educational status, marital status and residence, and clinical data such as skin type, duration of disease, pattern of hair loss, severity of involvement by “Severity of alopecia tool,” use of camouflage and previous treatments were noted.[15]

Stigmatization questionnaire

Patients were asked to complete the 28-items modified stigmatization questionnaire developed by Ginsburg and Bink by choosing one of the following six options: 0 = I absolutely do not agree, 1 = I do not agree, 2 = I partially do not agree, 3 = I partially agree, 4 = I agree, and 5 = I absolutely agree.[3] Reverse scoring was adopted for some of the items. The total score ranged from 0 to 140. Feeling of stigmatization was considered higher as patients scored higher.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by SPSS version 18.0 (IBM Co., Chicago, IL, USA). Characteristics of the population were determined using descriptive methods. Nonparametric tests were employed, as data did not distribute normally. Mann–Whitney U-test was used for the comparison of scores between groups. Pearson's and Kendall's tau correlation tests were used for the assessment of correlation between total stigmatization scores and dermatological and clinical data. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups

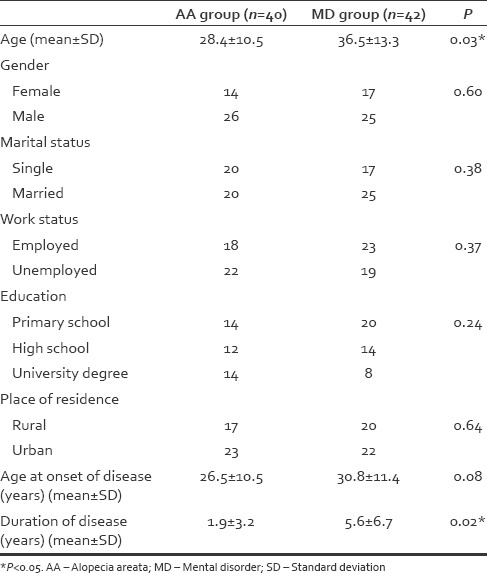

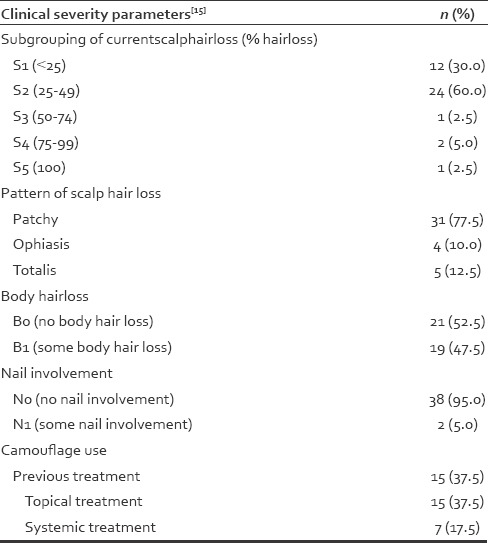

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AA and patients with MD are depicted in Table 1. Patients with AA and patients with MD did not differ significantly in gender, marital status, and education except age. The mean age of the patients with AA was 28.4 ± 10.5 years, and that of the MD group was 36.5 ± 13.3 years. The difference in the mean age between groups was significant (P = 0.03). Clinical severity, patterns of hair loss, and camouflage use in patients with AA are shown in Table 2. Fifteen patients stated that they routinely referred to various methods to hide their lesions.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with alopecia areata and mental disorder

Table 2.

Clinical severity of patients with alopecia areata

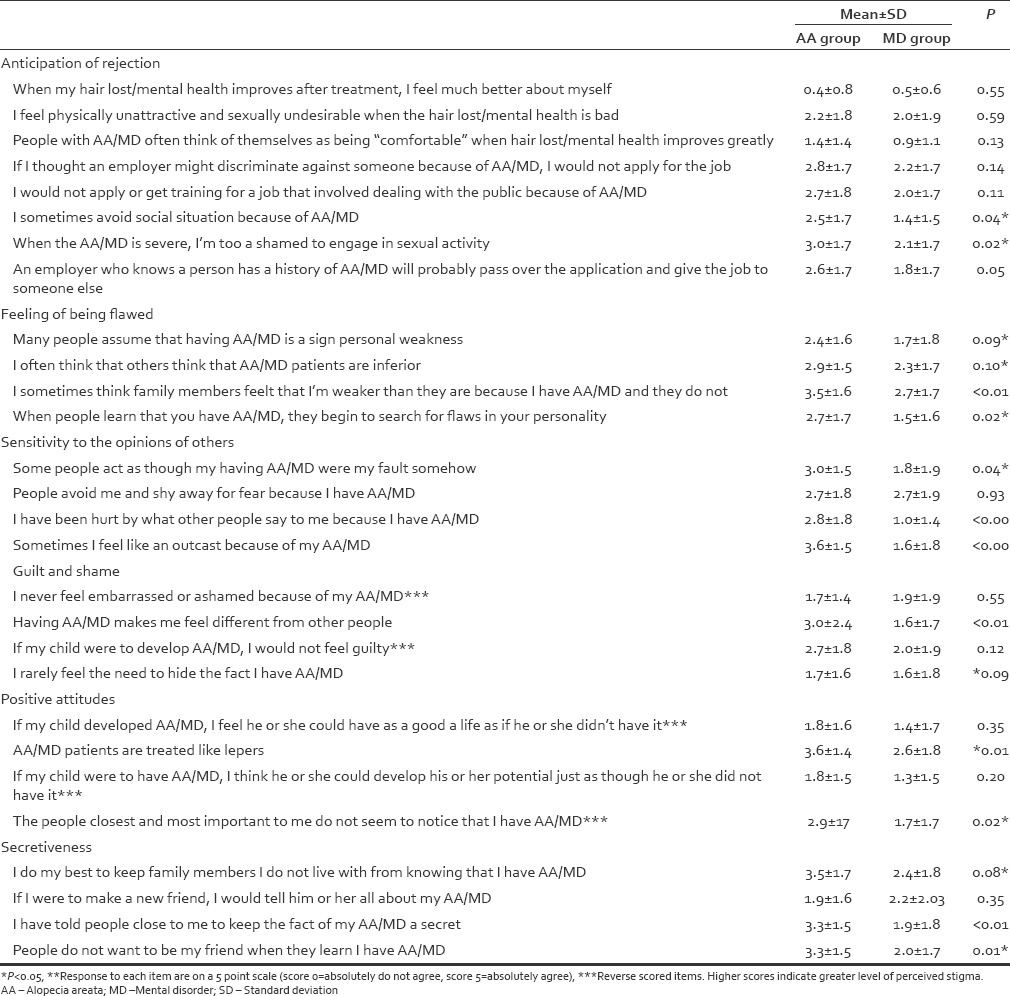

Comparison between groups on the perceived stigma

Responses of the both groups on the perceived stigma scale were presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Perceived stigma scale items and scores in patients with alopecia areata and mental disorder

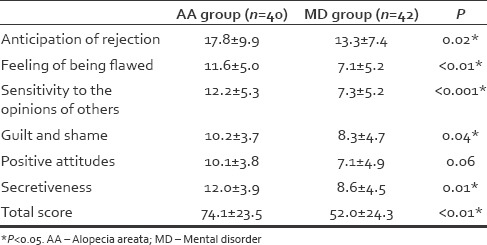

Total and subscales of perceived stigma scores were higher in the group of patients with the AA compared to the patients with MD [Table 4].

Table 4.

Stigma scale characteristics and scores in patients with alopecia areata and mental disorder

In both groups, the level of perceived stigma did not differ significantly according to gender, marital status, education years.

We conducted correlation analysis between total perceived stigma scores and age at disease onset and duration of disease. The analysis revealed no correlation in both groups. In AA group, the stigma scores did not correlate with clinical severity of disease, pattern of hair loss, and camouflage use.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate the perceived stigma in patients with AA and to compare it with patients with MD. MD was one of the most stigmatized medical conditions, which has been confirmed in many studies.[12,13] Previous studies support the use of the feelings of stigmatization questionnaire by Ginsburg and Link as an evaluation tool for perceived stigma in dermatology patients.[3,16,17] However, there are no studies available on its use in patients with MD. We thought it would be interesting to assess the perceived stigma by using this scale with regard to MD to be able to compare these two conditions. In our study, the results showed that individuals with AA reported more stigma compared to patients with MD. This suggests that AA is a condition that leads to more self-stigmatization than MD. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, patients with AA may not hide their lost hair or have difficulties in hiding, whereas MD can often be concealed. Previous studies revealed in physical and mental illnesses, if an individual could not manage to conceal ones’ illness, the level of stigmatization could increase.[16,18,19] Although we did not find any correlation with camouflage use and perceived stigma scores, in our AA group 37.5% were concealing or trying to conceal their disease. Second, although AA is merely seen as a skin disorder, it has been found to be associated with higher level of anxiety, depression and lower self-esteem, poor quality of life, which may contribute to the level of perceived stigma.[20,21,22,23,24,25] Thus, these psychological consequences could result in a double stigma in patients with AA. Besides, it should be kept in mind that in our study, AA group was younger when compared with MD group and it was reported that age may have a significant impact on perceived stigma.[26]

In the literature, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study to explore perceived stigma in patients with AA who were seeking treatment in dermatology setting. Some studies conducted in patients with chemotherapy induced alopecia have concentrated on perceived stigma.[27,28] These studies found that these patients often feel stigmatized by others. In addition, for women subjects, hair loss makes them feel unattractive and look like they are sick or dying.[29] On the other hand, for men, the lack of hair made them look child-like, vulnerable, and less macho.[30]

AA is a cosmetically very disfiguring clinical picture.[31] According to sociocultural perspective, women are more concerned about physical appearance than men.[32] We did not find any gender effect on perceived stigma in patients with AA. Some researchers have found that women with AA suffered from more negative psychological effects of hair loss compared to men.[33] In individuals who get a disease or disorder related to body image and appearance, such as obesity, vitiligo and psoriasis, perceived stigma was more commonly reported in women than in men. Further studies are needed to be performed with larger populations in order to detect possible role of gender in patients with AA.[3,8,34]

We found that perceived scores were not correlated with age at disease onset and duration of disease. It appears that patients are unable to reduce their self-stigma during course of their illness. This result is line with Yen et al.'s study.[35] However, Ginsburg and Link's study detected this relationship.[3] In this study, Ginsburg and Link's questionnaire was modified.[3] This may explain why we did not found any correlation between perceived stigma scores and duration of illness.

In our study, there was no relationship between perceived stigma and sociodemographic variables in either AA or MD group, which is in line with previous studies.[36,37] However, some authors reported that perceived stigma is related with education, marital status and occupational status.[24,38]

The clinical severity of visible skin disease is expected to increase the level of felt stigma. In a German study among vitiligo patients, patients with visible skin lesions were found to have higher total stigma scores than those with nonvisible lesions.[8] In another study by Krüger et al., recruited among children with vitiligo, patients with facial lesions and the ones’ using camouflage had higher stigma scores.[39] On the contrary, the stigma scores of AA patients were not related to the severity of disease and camouflage use. A similar result was yielded for psoriasis patients in a study by Hrehorów et al.[37] The authors explain this result by the fact that having psoriasis itself is a major cause of feeling stigmatized. According to us, the presence of a visible hair loss is the main cause of stigma, not the extent of hair loss.

There are several limitations to the present study. First, the sample size was small, highly selective, and consistent of individuals attending to dermatology and psychiatry outpatients’ clinics, results cannot be generalized to patients with AA and MD as a whole. Second, our study is a cross-sectional study, which does not allow the exact determination of the effect of sociodemographic factors on perceived stigma. Third, the design of study relies on self-reporting. Thus, some participants may not reflect their true feeling or behavior. Fourth, we have no control group without MD. If that were possible, it would have been better understand the dynamics of similarities and differences between groups.

CONCLUSION

We found that AA is a condition that can lead to more self-stigmatization than MD. No significant relationship was found between level of perceived stigma and demographic variables in both AA and MD group.

The level of perceived stigma needs to be considered in assessment of patients with AA. The recognition of the possibility that high level of perceived stigma may affect adherence to AA treatment should also be kept mind by dermatologist. Further studies with larger samples should be carried out to explore level of perceived stigma in AA.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grimalt R. Psychological aspects of hair disease. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2005;4:142–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2005.40218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaturvedi SK, Singh G, Gupta N. Stigma experience in skin disorders: An Indian perspective. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardy D, Besser A, Amir M, Gesthalter B, Biton A, Buskila D. Experiences of stigmatization play a role in mediating the impact of disease severity on quality of life in psoriasis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:736–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid-Ott G, Burchard R, Niederauer HH, Lamprecht F, Künsebeck HW. Stigmatization and quality of life of patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Hautarzt. 2003;54:852–7. doi: 10.1007/s00105-003-0539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Böhm D, Stock Gissendanner S, Bangemann K, Snitjer I, Werfel T, Weyergraf A, et al. Perceived relationships between severity of psoriasis symptoms, gender, stigmatization and quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:220–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szepietowski JC, Reich A National Quality of Life in Dermatology Group. Stigmatisation in onychomycosis patients: A population-based study. Mycoses. 2009;52:343–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid-Ott G, Künsebeck HW, Jecht E, Shimshoni R, Lazaroff I, Schallmayer S, et al. Stigmatization experience, coping and sense of coherence in vitiligo patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:456–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkhalifah A, Alsantali A, Wang E, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Alopecia areata update: Part I. Clinical picture, histopathology, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:177–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manolache L, Benea V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:921–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Firooz A, Firoozabadi MR, Ghazisaidi B, Dowlati Y. Concepts of patients with alopecia areata about their disease. BMC Dermatol. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penn DL, Kohlmaier JR, Corrigan PW. Interpersonal factors contributing to the stigma of schizophrenia: Social skills, perceived attractiveness, and symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2000;45:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latalova K, Ociskova M, Prasko J, Kamaradova D, Jelenova D, Sedlackova Z. Self-stigmatization in patients with bipolar disorder. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2013;34:265–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Washington: First Published in United States by American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, Roberts JL, Shapiro J, Canfield D, et al. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:440–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kent G. Correlates of perceived stigma in vitiligo. Psychol Health. 1999;14:241–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid-Ott G, Kuensebeck HW, Jaeger B, Werfel T, Frahm K, Ruitman J, et al. Validity study for the stigmatization experience in atopic dermatitis and psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:443–7. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dinos S, Stevens S, Serfaty M, Weich S, King M. Stigma: The feelings and experiences of 46 people with mental illness. Qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:176–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joachim G, Acorn S. Stigma of visible and invisible chronic conditions. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:243–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alfani S, Antinone V, Mozzetta A, Di Pietro C, Mazzanti C, Stella P, et al. Psychological status of patients with alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:304–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grahovac T, Ruzic K, Sepic-Grahovac D, Dadic-Hero E, Radonja AP. Depressive disorder and alopecia. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:293–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi Q, Duvic M, Osei JS, Hordinsky MK, Norris DA, Price VH, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in alopecia areata patients-A secondary analysis of the National Alopecia Areata Registry Data. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S49–50. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2013.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alonso J, Buron A, Bruffaerts R, He Y, Posada-Villa J, Lepine JP, et al. Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the World Mental Health Surveys. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:305–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgener SC, Buckwalter K, Perkhounkova Y, Liu MF. The effects of perceived stigma on quality of life outcomes in persons with early-stage dementia: Longitudinal findings: Part 2. Dementia (London) 2015;14:609–32. doi: 10.1177/1471301213504202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bielen I, Friedrich L, Sruk A, Prvan MP, Hajnšek S, Petelin Z, et al. Factors associated with perceived stigma of epilepsy in Croatia: A study using the revised Epilepsy Stigma Scale. Seizure. 2014;23:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosman S. Cancer and stigma: Experience of patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:333–9. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harcourt D, Frith H. Women's experiences of an altered appearance during chemotherapy: An indication of cancer status. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:597–606. doi: 10.1177/1359105308090932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kathryn C, Lisa S, Cecilia R, Marie S. The enigma of the stigma of hair loss. Why is cancer-treatment related alopecia so traumatic for women. Open Cancer J. 2013;6:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilton S, Hunt K, Emslie C, Salinas M, Ziebland S. Have men been overlooked. A comparison of young men and women's experiences of chemotherapy-induced alopecia? Psychooncology. 2008;17:577–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venten I, Hess N, Hirschmüller A, Altmeyer P, Brockmeyer N. Treatment of therapy-resistant Alopecia areata with fumaric acid esters. Eur J Med Res. 2006;11:300–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson LA. Physical Appearance and Gender: Sociobiological and Sociocultural Perspectives. Albany: Suny Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welsh N, Guy A. The lived experience of alopecia areata: A qualitative study. Body Image. 2009;6:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hebl MR, Heatherton TF. The stigma of obesity in women: The difference is black and white. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1998;24:417–26. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, Tang TC, Yen JY, Ko CH. Self-stigma and its correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:599–601. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ertugrul A, Ulug B. Perception of stigma among patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:73–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak L, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:67–72. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu Y, Duller P, Van Der Valk PG, Evers AW. Helplessness as predictor of perceived stigmatization in patients with psoriasis atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Pschosom. 2003;4:146–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krüger C, Panske A, Schallreuter KU. Disease-related behavioral patterns and experiences affect quality of life in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]