Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors comprise a heterogeneous group of malignancies with a broad spectrum of clinical behavior. Poorly differentiated tumors follow an aggressive course with limited treatment options, and new approaches are needed. Oncogenic BRAF V600E (BRAFV600E) substitutions are observed primarily in melanoma, colon cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer, but have been identified in multiple tumor types. Here we describe the first reported recurrent BRAFV600E mutations in advanced high grade colorectal neuroendocrine tumors, and identify BRAF alteration frequency of 9% in 108 cases. Among these BRAF alterations 80% were BRAFV600E. Dramatic response to BRAF-MEK combination occurred in two cases of metastatic high grade rectal neuroendocrine carcinoma refractory to standard therapy. Urinary BRAFV600E circulating tumor DNA monitoring paralleled disease response. Our series represents the largest study of genomic profiling in colorectal neuroendocrine tumors and provides strong evidence that BRAFV600E is an oncogenic driver responsive to BRAF/MEK combination therapy in this molecular subset.

Keywords: BRAF, neuroendocrine, genomic profiling, trametinib, dabrafenib, MEK

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the digestive tract are increasing, with an estimated annual incidence of 3.65/100,000 [1]. The current therapeutic approach is dictated by site of origin, disease stage, and surrogate biologic features such as proliferative rate and overall histologic grade. Surgical resection is frequently undertaken in non-metastatic disease although is rarely curative due to distant failure and large prospective studies to guide therapy are lacking. Poorly differentiated (high-grade) NETs are often considered for small-cell lung cancer (SCLC)-like chemotherapies based on aggressive biologic behavior and data from small retrospective series suggesting a multimodality approach with chemoradiation and surgery may be optimal for localized non-pancreatic high grade NETs [2–4]. The prognosis for advanced high-grade NETs remains poor, with median survival less than 12 months [5, 6].

The molecular features of NETs are not comprehensively characterized and have focused on alterations in the tumor suppressor MEN1, occurring primarily in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs), which differ from non-pancreatic NETs [7–9]. Limited data exist on molecular features in non-pancreatic NETs and alterations in SRC, SMAD family genes, AURKA, EGFR, HSP90, PDGFR and amplification of AKT1 and AKT2 were observed in a limited series of low grade, well-differentiated small intestinal NETs [10]. Colorectal and high grade NETs are even less well characterized, further limiting therapeutic options.

Here we identified recurrent somatic BRAF alterations in high grade colorectal NETs and describe two patients with treatment-refractory metastatic high grade rectal NET harboring a BRAFV600E substitution who achieved a rapid and dramatic response to combination BRAF/MEK directed therapy. This is the largest published colorectal NET series and the first reported oncogenic BRAF mutation in high grade NET, demonstrating the ability of genomic profiling to identify therapeutically relevant alterations in this aggressive disease with no standard treatment approach.

Results

Case 1

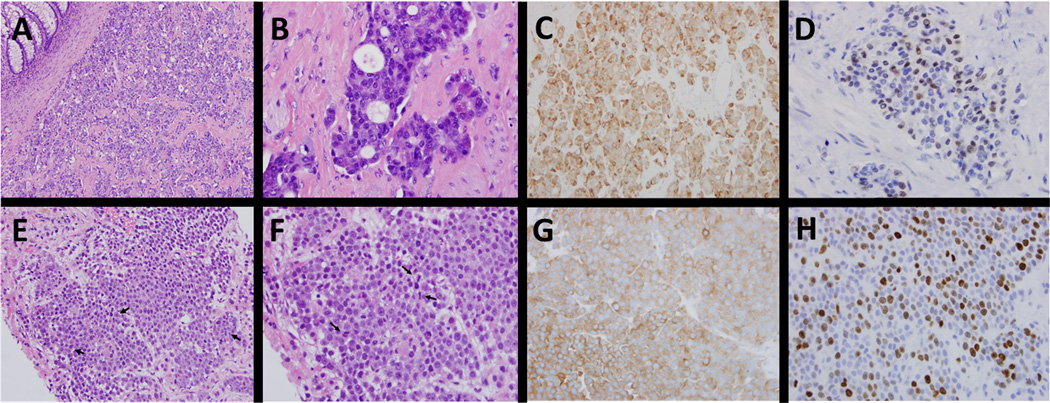

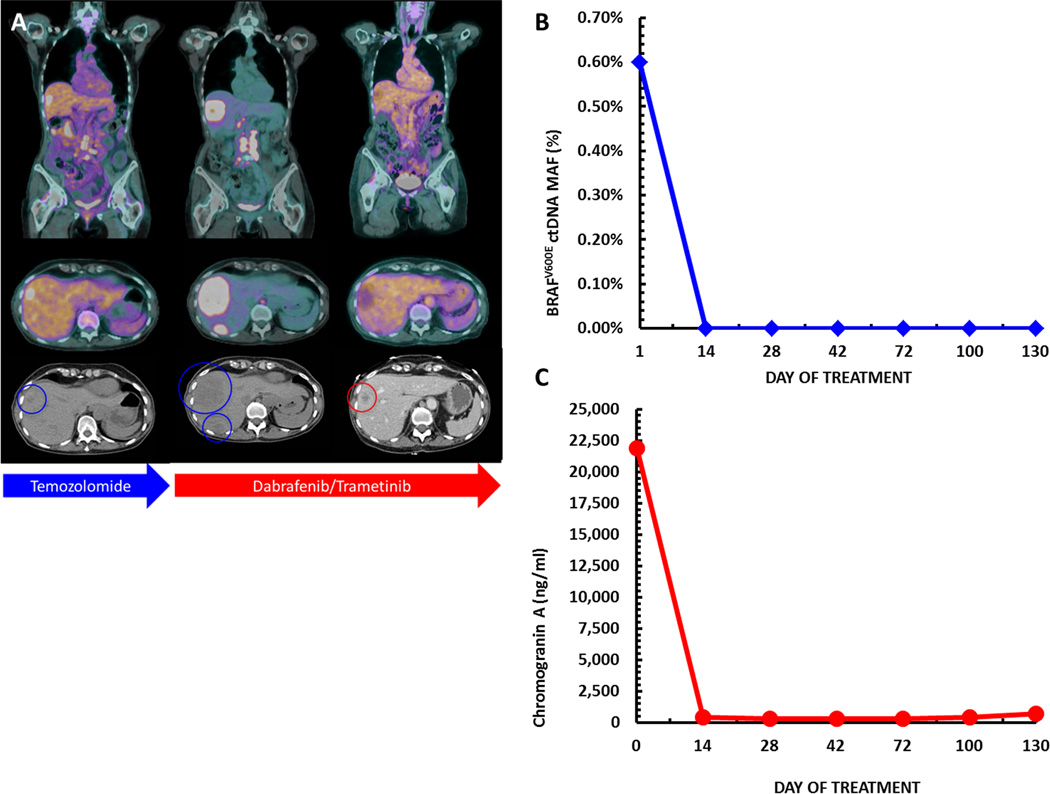

A 70-year-old female presented with rectal bleeding from a fungating rectal mass, which on biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated high-grade (grade 3) rectal neuroendocrine tumor with a Ki67 proliferation index greater than 60% (figure 1A-D). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated microsatellite stability (MSI-stable). She received neoadjuvant chemoradiation with carboplatin and etoposide followed by low anterior resection and end colostomy. Histopathologic analysis confirmed residual neuroendocrine tumor, grade 2/3, Ki67- 3–4%, positive margins, and 4/22 positive lymph nodes. A PET-CT one month post-resection demonstrated metastatic disease, confirmed on liver biopsy as high grade NET (figures 1E-H, 2A). She was treated with temozolomide but developed rapid radiographic progression, left leg paresthesia and abdominal pain within three months of therapy (figure 2A). To investigate further therapeutic options her liver biopsy was subjected to comprehensive genomic profiling as previously described [11]. Genomic analysis revealed a BRAFV600E substitution at a mutant allele frequency (MAF) of 26% with a median sample coverage depth of 529x (table 1). The initial surgical specimen was retrospectively tested and also found to harbor a BRAFV600E mutation. In the absence of an available clinical trial she was transitioned to dabrafenib 150mg twice daily and trametinib 2mg once daily and her symptoms resolved within 10 days of treatment. Concurrent decrease in serum chromogranin A and urinary BRAFV600E circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) using a clinical laboratory improvement amendment (CLIA) approved assay correlated with rapid disease response (figure 2B-C). She obtained a dramatic radiographic response within five weeks that continues for over seven months at the time of submission (figure 2A). Serial chromogranin A remains decreased and a quantitative algorithm applied to the CLIA test result indicated a non-detectable urinary BRAFV600E level from a peak ctDNA MAF of 0.6% (figure 2B-C).

Figure 1.

Comparison of histologic features between primary rectal neuroendocrine tumor and liver metastasis. Histologic examination show a submucosal mass consisting of nested/organoid proliferation of variably small cells with stippled chromatin with some cells exhibiting pink granular cytoplasm (A-B). Immunohistochemical stains are diffusely positive for synaptophysin (C) and chromogranin (not shown), with variable CDX2 staining (D). Panels E-H highlight similar features from the liver biopsy with uniform cells (E-F), scattered mitotic figures (arrows), diffuse synaptophysin positivity (G) and Ki67 proliferative index 40–50% (H).

Figure 2.

Serial imaging demonstrating progression on temozolomide followed by rapid and durable response to dabrafenib and trametinib in a patient with a refractory BRAF mutant rectal neuroendocrine tumor (panel A). Parallel decrease in serum chromogranin A and quantitative urine BRAF ctDNA detection are shown in panels B and C respectively.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of BRAF alterations in high grade colorectal neuroendocrine tumors.

| Case | Age | Sex | Tumor Location |

Stage, Grade |

KRAS, APC Status |

BRAF Event |

Tumor Purity (%) |

BRAF MAF (%) |

BRAF Coverage |

Sample Coverage |

Response to BRAF-i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 70 | F | Rectum | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 59 | 26 | 463 | 529 | Yes |

| 2 | 39 | F | Rectum | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 49 | 53 | 734 | 647 | Yes |

| 3 | 64 | M | Rectum | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: R1114* APC: V1414fs*1 |

G469A | 80 | 55 | 1446 | 904 | N/A |

| 4 | 66 | M | Colon | IV, 2 |

KRAS: G12S APC: WT |

V600E | 36 | 1 | 402 | 459 | N/A |

| 5 | 51 | F | Colon | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: R554* APC: Q1541* |

V600E | 30 | 31 | 372 | 445 | N/A |

| 6 | 62 | M | Colon | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 78 | 54 | 1079 | 596 | N/A |

| 7 | 78 | M | Rectum | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 60 | 34 | 612 | 430 | N/A |

| 8 | 45 | F | Colon | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 66 | 42 | 587 | 436 | N/A |

| 9 | 70 | M | Colon | IV, 2 |

KRAS: A146T APC: R1450* |

R671Q | 30 | 44 | 636 | 612 | N/A |

| 10 | 69 | F | Rectum | IV, 3 |

KRAS: WT APC: WT |

V600E | 19 | 9 | 552 | 575 | N/A |

Abbreviations: F; female, M; male, MAF; mutant allele frequency, WT; wild type, N/A; data not available.

Asterisk (*) represents the incident case, case 1.

Case 2

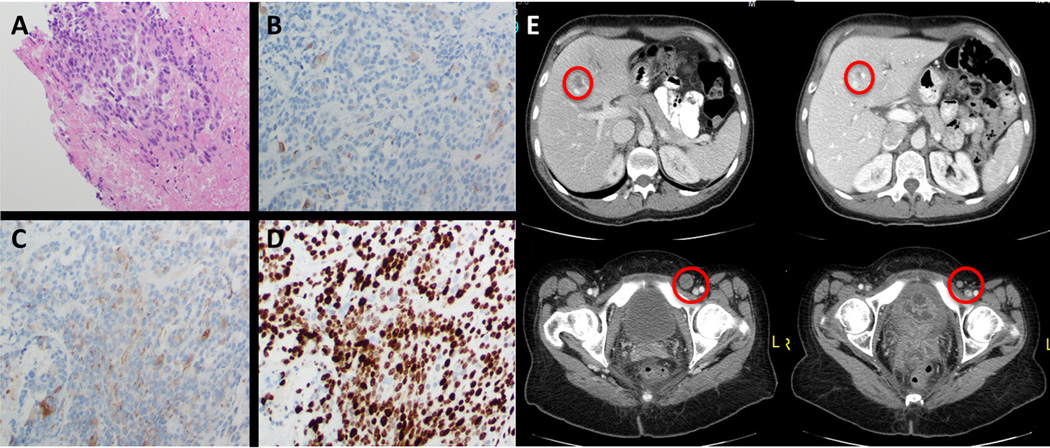

A 39 year-old woman presented with rectal bleeding and was found to have a large locally advanced high-grade rectal neuroendocrine tumor with a proliferative index of over 70% (figure 3A-D). She was treated with cisplatin and etoposide for 3 cycles with concurrent radiation but developed progressive disease with hepatic, pulmonary, and inguinal nodal metastases. She received Carboplatin/Docetaxel for 6 cycles and achieved initial stable disease followed by disease progression and worsening rectal pain. Comprehensive genomic profiling of the rectal mass revealed a BRAFV600E substitution at a MAF of 53% at a coverage depth of 734x (table 1). An appropriate clinical trial was not available and she was treated with vemurafenib 960mg twice daily and trametinib 2mg once daily and achieved a resolution of her pain within three days followed by a dramatic radiographic response (figure 3E). She remains on combination BRAF/MEK therapy with an ongoing response lasting 9 months.

Figure 3.

Histologic features and radiographic response to vemurafenib and trametinib in BRAFV600E mutant high grade rectal neuroendocrine tumor from case 2. Microscopic examination demonstrates organization of variably small cells (A) staining weakly positive for CD56 (B) and chromogranin (C) with a Ki67 proliferative index of over 70% (D). Dramatic radiographic response to therapy is shown in panel E.

BRAF Alterations Occur Frequently in Advanced Colorectal NET

To identify additional neuroendocrine cases harboring BRAF alterations we retrospectively reviewed a database of over 55,000 clinical samples subjected to comprehensive genomic profiling as previously described [11]. Including the incident case (case 1) we identified a total of 109 cases of colorectal NETs. Ten samples (9%) harbored alterations in BRAF (80% BRAFV600E) (table 1). Two non-V600 alterations (G469A, and R671Q) were found. BRAFV600E was mutually exclusive with oncogenic KRAS/NRAS alterations and other established driver alterations (table 1). Among the 109 colorectal NETs alterations in NRAS were observed in 2/109 (1.8%) and KRAS alterations occurred in a total of 35/109 cases (32%). Mean age was 61.4 years, and BRAF alterations were split between male and female patients and colon and rectal locations. The majority of BRAF mutant samples (8/10) were of high grade (grade 3) histologic appearance (table 1). PIK3CA E545K and N1068fs*3 alterations occurred in cases 5 and 9 respectively (table 1). Other established oncogenic genomic alterations and alterations in MLH1, MSH6, and MSH2 were not identified.

Discussion

Here we identify recurrent somatic BRAF alterations in high grade colorectal NET and demonstrate rapid clinical improvement and tumor responses with combination BRAF and MEK directed therapies.

The rectum is the most common site of NET involvement, comprising of 29% of all gastroenteropancreatic (GEP) NETs [1]. Outside of colorectal adenocarcinoma, BRAF mutations (5–9%) have not been described in tubular GI malignancies in the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) or catalogue of somatic mutation in cancer (COSMIC) datasets. However, neuroendocrine tumors are significantly under-represented and true BRAF alteration frequency is likely underestimated. In our database including 109 colorectal neuroendocrine tumor samples, we identified BRAF mutations at a frequency of 9% with the vast majority being BRAFV600E. Our homogenous series suggests BRAFV600E are more common (9%) than previous limited studies of non-pancreatic NETs had indicated [10, 12]. Recently, a subset of colorectal adenocarcinomas with large cell neuroendocrine features and signet ring cells in which BRAF alterations may be enriched has been described, although the clinical impact is not known [13]. Review of our cases did not identify signet ring features. Our series represents the largest dataset of colorectal NETs subjected to comprehensive genomic profiling, and suggests further clinical investigation with BRAF-directed therapies is warranted in high grade colorectal NETs. Interestingly, alterations in KRAS/NRAS were 34%, significantly lower than the 45–53% incidence of KRAS/NRAS alterations reported from colorectal adenocarcinoma [14, 15]. Whether or not these frequencies suggest a shared origin with early evolutionary divergence is beyond the scope of our study. In our samples, BRAF mutations and oncogenic KRAS alterations were mutually exclusive, consistent with observations in traditional colorectal adenocarcinoma.

The rationale for the superiority of combined BRAF and MEK inhibition over BRAF monotherapy is well established in BRAFV600E mutant melanoma [16, 17]. Recently vemurafenib monotherapy demonstrated benefit across multiple tumor types, and combination BRAF/MEK inhibition in BRAFV600E rare tumors is the subject of an ongoing study (NCT02034110) [18]. However, vemurafenib monotherapy is not active in BRAFV600E colorectal cancers owing to the rapid development of EGFR-mediated feedback MAPK reactivation [19, 20]. BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer are commonly associated with right-sided lesions originating from serrated adenomas with high rates of hypermethylation and microsatellite instability, something not observed in our cases [14, 21]. Recently, the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib in BRAFV600E mutant advanced CRC confirmed a partial response rate of 12% (5/43) and one durable complete response [22]. Whether or not neuroendocrine features were present in the complete response observed by Corcoran et al. is not reported. Although limited by small numbers, both patient responses in our series occurred in rectal patients with high grade NETs wild type for KRAS, APC, and PIK3CA (table 1). Although the BRAFG469A is frequently observed in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and known to activate downstream MAPK signaling the responsiveness to BRAF and MEK inhibition is not well studied [23]. Similarly, case 4 in our series harbors a concurrent KRASG12S and a BRAFV600E at a low MAF (1%). Recently, the KRASG12S was shown to be non-tumorigenic in a pancreatic cancer model [24]. More data is needed to determine the impact of concurrent exon 2 KRAS mutations on BRAF-inhibitor sensitivity in BRAF-mutant colorectal adenocarcinomas and high grade colorectal NETs [24, 25]. Despite sharing anatomic locations within the colon our results are suggestive of significant biologic differences between advanced colorectal adenocarcinomas and high grade colorectal NETs. Functional validation in preclinical studies will be an important step in determining the behavior and genomic context of response in BRAF mutant NET.

Following initiation of therapy, there was a rapid decrease in urinary BRAFV600E ctDNA, along with serum chromogranin A levels that paralleled clinical resolution of symptoms and preceded radiologic response. While the serum chromogranin A never completely normalized the correlation between serum chromogranin A, clinical improvement, and BRAFV600E urinary ctDNA detection (lower limit 0.03% MAF) provides early validation for clinical utility of ctDNA testing methodologies in monitoring of tumor dynamics [26]. Non-invasive methodologies allowing for molecular monitoring will play an increasing role in future clinical care, particularly in monitoring for drug resistance and early progression/recurrence [26].

Recent data suggests that in BRAFV600E colorectal cancer resistance to combination BRAF/MEK may be mediated by acquired MEK1 (MAP2K1) alterations (MEK1F53L) [27]. Further work focusing on combination therapies and refining understanding of resistance will be essential to optimize outcomes in rare tumors harboring BRAF alterations, including our cases.

Overall our series underscores the oncogenic potential and a therapeutic implication of BRAF-directed therapies in high grade colorectal NETs, and identifies a new molecularly defined disease subset. Although prospective validation through clinical trials is the optimal approach to confirm our findings, this was not available to either of our patients, and important issues surrounding off-label treatment costs are beyond the scope of this report.

Methods

Next generation sequencing (NGS) analysis of tumor biopsies

DNA and RNA were extracted and adaptor ligated sequencing libraries were captured by solution hybridization using custom bait-sets targeting 315 cancer-related genes and 28 frequently rearranged genes by DNA-seq (FoundationOne, Foundation Medicine, Cambridge, MA). All captured libraries were sequenced to high depth (Illumina HiSeq) in a CLIA-certified CAP accredited laboratory (Foundation Medicine), averaging >500x for DNA. Sequence data from gDNA and cDNA were mapped to the reference human genome (hg19) and analyzed through a computational analysis pipeline to call genomic alterations present in the sample, including substitutions, short insertions and deletions, rearrangements and copy-number variants.

Identification of BRAF altered NET

Following identification of BRAFV600E in the incident case (case 1) a large database containing comprehensive genomic profiling sequencing data for over 55,000 clinical samples was retrospectively interrogated to identify additional neuroendocrine patient samples. DNA sequences associated with clinical samples carrying a colorectal neuroendocrine diagnosis were analyzed for base substitutions, short insertions, deletions, gene copy number alterations (focal amplifications and homozygous deletions) and gene fusions. Basic clinicopathologic characteristics were captured; however, treatment and disease response data were not available in all cases.

Detection of BRAF V600E in Urinary ctDNA

Urinary ctDNA BRAFV600E test for qualitative detection of BRAFV600E was performed in CLIA-certified CAP accredited laboratory (Trovagene, San Diego, CA) as previously described [28]. Following urinary ctDNA extraction and quantitation, a two-step PCR assay targeting a very short (31 bp) amplicon was employed to enhance detection of rare mutant alleles in ctDNA. The first-step amplification was done with two primers flanking the BRAFV600 locus and a complementary blocking oligonucleotide, which suppressed wild-type BRAF amplification, achieving enrichment of the mutant BRAFV600E sequence. The second step entailed a duplex ddPCR reaction using FAM (BRAFV600E) and VIC (wild-type BRAF) TaqMan probes to enable quantification of mutant versus wild-type fragments, respectively. The RainDrop ddPCR platform (Rain-Dance) was used for PCR droplet separation, fluorescent reading, and counting droplets containing mutant sequence, wild-type sequence, or unreacted probe. For each patient sample, the assay identified BRAFV600E mutant fragments detected as a percentage of detected wild-type BRAF. Thresholds for BRAFV600E detection were developed by evaluating a training set of urinary ctDNA from patients with BRAFV600E metastatic cancer (positives) and healthy volunteers (negatives) by applying a classification tree algorithm that maximizes the true-positive and true-negative rates, yielding two threshold values (< 0.05 not detected; 0.05–0.107 indeterminate; >0.107 detected; ref. 25). A quantitative algorithm was applied to the CLIA test result to obtain the values for BRAFV600E allele frequencies.

Patient studies

Review of available treatment options and detailed risk-benefit discussion was undertaken and informed consent was obtained from both patients prior to treatment initiation. Patient care was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Study medications were obtained through insurance and/or the drug manufacturer and monitored in accordance with the approved label. Treatment was conducted in the absence of institutional review board approval.

Statement of Significance.

BRAFV600E is an established oncogenic driver but significant disparities in response exist among tumor types. Two patients with treatment-refractory high-grade colorectal neuroendocrine tumor harboring BRAFV600E exhibited rapid and durable response to combined BRAF/MEK inhibition providing the first clinical evidence of efficacy in this aggressive tumor type.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the important contributions of researchers whose work could not be cited due to space limitations.

Financial Support

S. J. Klempner was partly supported by the University of California Irvine NIH P30 grant CA062203.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

KG, AS, JR, VAM, PJS, and SMA are stockholders and employees of Foundation Medicine.

MGE is a stockholder and employee of Trovagene. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Chan A, Svejda B, Kidd M, Modlin IM. The epidemiology of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner B, Tang LH, Klimstra DS, Kelsen DP. Small-cell carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2730–2739. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janson ET, Sorbye H, Welin S, Federspiel B, Gronbaek H, Hellman P, et al. Nordic guidelines 2014 for diagnosis and treatment of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1284–1297. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.941999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fjallskog ML, Granberg DP, Welin SL, Eriksson C, Oberg KE, Janson ET, et al. Treatment with cisplatin and etoposide in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2001;92:1101–1107. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010901)92:5<1101::aid-cncr1426>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sorbye H, Welin S, Langer SW, Vestermark LW, Holt N, Osterlund P, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors for treatment and survival in 305 patients with advanced gastrointestinal neuroendocrine carcinoma (WHO G3): the NORDIC NEC study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:152–160. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorbye H, Strosberg J, Baudin E, Klimstra DS, Yao JC. Gastroenteropancreatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancer. 2014;120:2814–2823. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, de Wilde RF, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011;331:1199–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadanandam A, Wullschleger S, Lyssiotis CA, Grotzinger C, Barbi S, Bersani S, et al. A Cross-Species Analysis in Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors Reveals Molecular Subtypes with Distinctive Clinical, Metastatic, Developmental, and Metabolic Characteristics. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1296–1313. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, Beghelli S, Falconi M, della Peruta M, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: expression profiling evidences a role for AKT-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:245–255. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banck MS, Kanwar R, Kulkarni AA, Boora GK, Metge F, Kipp BR, et al. The genomic landscape of small intestine neuroendocrine tumors. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2502–2508. doi: 10.1172/JCI67963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleist B, Kempa M, Novy M, Oberkanins C, Xu L, Li G, et al. Comparison of neuroendocrine differentiation and KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA/TP53 mutation status in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:5927–5939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olevian DC, Nikiforova MN, Chiosea S, Sun W, Bahary N, Kuan SF, et al. Colorectal poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas frequently exhibit BRAF mutations and are associated with poor overall survival. Hum Pathol. 2016;49:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorich MJ, Wiese MD, Rowland A, Kichenadasse G, McKinnon RA, Karapetis CS. Extended RAS mutations and anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody survival benefit in metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:13–21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:444–451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroiakovski D, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:30–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay JY, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:726–736. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:227–235. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Liao X, Yamauchi M, Nishihara R, et al. Microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1151–1156. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS, Kwak EL, Ryan DP, Bendell JC, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition With Dabrafenib and Trametinib in BRAF V600-Mutant Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4023–4031. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, Sima CS, Miller VA, Kris MG, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2046–2051. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park JT, Johnson N, Liu S, Levesque M, Wang YJ, Ho H, et al. Differential in vivo tumorigenicity of diverse KRAS mutations in vertebrate pancreas: A comprehensive survey. Oncogene. 2015;34:2801–2806. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, Hecht JR, O'Dwyer PJ, Maru D, et al. Phase II Pilot Study of Vemurafenib in Patients With Metastatic BRAF-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:4032–4038. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyman DM, Diamond EL, Vibat CR, Hassaine L, Poole JC, Patel M, et al. Prospective blinded study of BRAFV600E mutation detection in cell-free DNA of patients with systemic histiocytic disorders. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:64–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahronian LG, Sennott EM, Van Allen EM, Wagle N, Kwak EL, Faris JE, et al. Clinical Acquired Resistance to RAF Inhibitor Combinations in BRAF-Mutant Colorectal Cancer through MAPK Pathway Alterations. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:358–367. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janku F, Vibat CR, Kosco K, Holley VR, Cabrilo G, Meric-Bernstam F, et al. BRAF V600E mutations in urine and plasma cell-free DNA from patients with Erdheim-Chester disease. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3607–3610. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]