Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is one of the most common inherited genetic diseases, caused by mutations in PKD1 and/ or PKD2. Infertility and reproductive tract abnormalities in male ADPKD patients are very common and have higher incidence than in the general population. In this work, we reveal novel roles of Pkd2 for male reproductive system development. Disruption of Pkd2 caused dilation of mesonephric tubules/efferent ducts, failure of epididymal coiling, and defective testicular development. Deletion of Pkd2 in the epithelia alone was sufficient to cause reproductive tract defects seen in Pkd2−/− mice, suggesting that epithelial Pkd2 plays a pivotal role for development and maintenance of the male reproductive tract. In the testis, Pkd2 also plays a role in interstitial tissue and testicular cord development. In-depth analysis of epithelial-specific knockout mice revealed that Pkd2 is critical to maintain cellular phenotype and developmental signaling in the male reproductive system. Taken together, our data for the first time reveal novel roles for Pkd2 in male reproductive system development and provide new insights in male reproductive system abnormality and infertility in ADPKD patients.

Keywords: Polycystin-2, Polycystic Kidney Disease, Efferent Duct, Epididymis, Testis, Mice

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is one of the most common genetic diseases in humans affecting all ethnic groups worldwide with an incidence up to 1 in 500. Renal pathogenesis of ADPKD is characterized by development of renal cysts, enlargement of kidneys and progressive loss of renal function. Over half of ADPKD patients proceed to end-stage renal disease by the fifth and sixth decades. ADPKD is caused by a spectrum of mutations in PKD1 on chromosome 16 and/or PKD2 gene on chromosome 4. PKD1 mutations account for over 85% of the cases; PKD2 mutations are responsible for the rest of the cases. Reproductive system abnormalities and infertility in male ADPKD patients are very common and have a higher incidence than in the general population, suggesting that ADPKD genes are required for development or maintenance of the male reproductive system (Belet et al., 2002; Kanagarajah et al., 2011; Manno et al., 2005; Torra et al., 2008; Vora et al., 2008).

The male reproductive system consists of a set of sex organs, including the paired testes and a network of excretory ducts known as the reproductive tract. The male reproductive tract consists of a number of sex accessary organs, including the efferent ducts, epididymis, vas deferens, and seminal vesicle on each side. The efferent ducts, connecting the testis to the epididymis, are formed by mesonephric tubule remodeling, while other structures are mostly derived from the Wolffian duct that is degenerated in females (Cornwall, 2009; Hannema and Hughes, 2007; Herpin and Schartl, 2011; Joseph et al., 2009). Testis development is initiated by establishment of a group of specialized epithelial cells during early gonadogenesis, the Sertoli cells, which are derived from the coelomic epithelium at the genital ridge (Brennan and Capel, 2004; Karl and Capel, 1998). The newly emerged Sertoli cells align around aggregates of the primordial germ cells (PGCs), which migrate to the genital ridge at an earlier stage (E8.5 to E9.5 in mice), to form the testicular cords (Brennan and Capel, 2004; Molyneaux and Wylie, 2004). An important function of the Sertoli cells is to secret anti- Müllerian hormone (AMH) to inhibit development of the female sex organ primordia. The interstitial compartment of the male gonad is formed by mesenchymal cells which migrate from the mesonephros during gonadogenesis (Brennan and Capel, 2004; Combes et al., 2009; Martineau et al., 1997). These mesenchymal cells differentiate into various cell types, including endothelial cells, peritubular myoid cells, and the Leydig cells (Brennan and Capel, 2004; Combes et al., 2009). The testicular cords, after being formed, continuously grow and convolute, and eventually mature into the seminiferous ducts. Sperm are generated in the testis and mature while migrating through the tortuous and lengthy reproductive tract.

In a previous study, we showed that the Pkd1 gene plays essential roles for male reproductive tract development (Nie and Arend, 2013). Here, we examined if Pkd2, is also required for male reproductive system development. The Pkd2 gene encodes polycystin-2 (PC-2), a membrane protein with six transmembrane domains that are homologous to the last six transmembrane domains of polycystin -1 (PC-1) (Cai et al., 1999; Chapin and Caplan, 2010; Wilson, 2001). Unlike PC-1, the N-terminal and C-terminal of PC-2 are both intracellularly located. PC-2 serves as an ion channel for a variety of cell types and is critical for development of a number of organ systems (Chapin and Caplan, 2010; Gonzalez-Perrett et al., 2001; Koulen et al., 2002; Tsiokas et al., 2007; Wilson, 2001). Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that PC-1 and PC-2 are co-localized in a variety of cell types. Physical interactions of PC-1 and PC-2 have also been detected at their intracellular domains (Casuscelli et al., 2009; Qian et al., 1997; Xu et al., 2003; Yoder et al., 2002). Further, disruption of Pkd1 and Pkd2 in mice results in similar phenotypes in many organ systems. Yet, Pkd2 also displays unique expression and functions that are not found for Pkd1. For example, Pkd2 is expressed in cells of the embryo node and plays an essential role for body left-right determination, in which Pkd1 is not required (Bataille et al., 2011; Yoshiba et al., 2012). Overall, Pkd1 and Pkd2 exert both common and independent functions during organogenesis. In this study, we reveal novel roles for Pkd2 in male reproductive system development.

Material and methods

Mice

Animal use protocol was approved by Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee. Pkd1LacZ/+(Pkd1+/−), Pkd2LoxP/LoxP, Pkd2+/− and Pax2-cre mice were described elsewhere (Bhunia et al., 2002; Garcia-Gonzalez et al., 2010; Ohyama and Groves, 2004; Wu et al., 2000). The mice were maintained in a mixed background and genotyped by PCR.

Histology, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Histology, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry were performed using paraffin sections at thickness of 7µm. Tissue preparation and embedding were performed using standard procedures. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used for histologic study. Immunohistochemical staining and immunofluorescence were performed using antibodies to PC-2 (Millipore), phospho-Smad2 (Cell signaling Technology), phospho-Smad1/5(Cell signaling Technology), pan-cytokeratin (sigma), β-catenin (Sigma), α-tubulin (Neomarkers), and laminin (Sigma). Secondary antibodies were either horseradish peroxidase (HRP) or fluorescence conjugated. Antibody dilution followed manufacturer’s recommendations. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) was used for HRP-mediated colour reaction.

Apoptosis and Proliferation assays

Paraffin sections were used for apoptosis and proliferation assays. TUNEL staining for apoptosis used the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche) and was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol. The phospho-histone H3 antibody (Millipore) was used for the proliferation assay. The fraction of phospho-histone H3 positive cells over total number of cells was used for proliferation index.

LacZ staining

Urogenital system primordia were dissected out from mouse embryos, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 hour at 4 °C, rinsed three times in 1× PBS, and stained overnight at room temperature in X-gal reaction solution containing 35mM potassium ferrocyanide, 35mM potassium ferricyanide, 2mM MgCl2, and 1mg/ml X-gal. Stained tissues were visualized in 80% glycerol or sectioned for microscopic examination.

RT-PCR and real-time qRT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the efferent ducts of three mice for each genotype with Purelink RNA mini kit (The life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using High Capacity RNA-to-DNA kit following the manufacturer's protocol (A&B Applied Biosystems). Primers for β-catenin were described elsewhere and confirmed with RT-PCR (Gilbert-Sirieix et al., 2011). The real-time PCR step was performed in a CFX Touch real-time PCR detecting system (Bio-Rad). Fluorescence was acquired at each cycle (40 amplification cycles). Ct values were normalized to that of GAPDH. Product specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis.

Western Blot

Frozen tissues of mouse reproductive system were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (50 µl RIPA per 1mg tissue). The homogenates were left on ice for 30 minutes, then heated at 95 °C for 5 minutes, and spun down at 11000g for 5 minutes. The supernatants were collected for western blot. About 40µg proteins were loaded for each genotype. Protein transfer was performed using a semi-dry system. HRP-mediated chemiluminescent signal was detected by a Kodak Digital Image Station 4000R system.

Results

Pkd2 encoded PC-2 expression in the male reproductive system

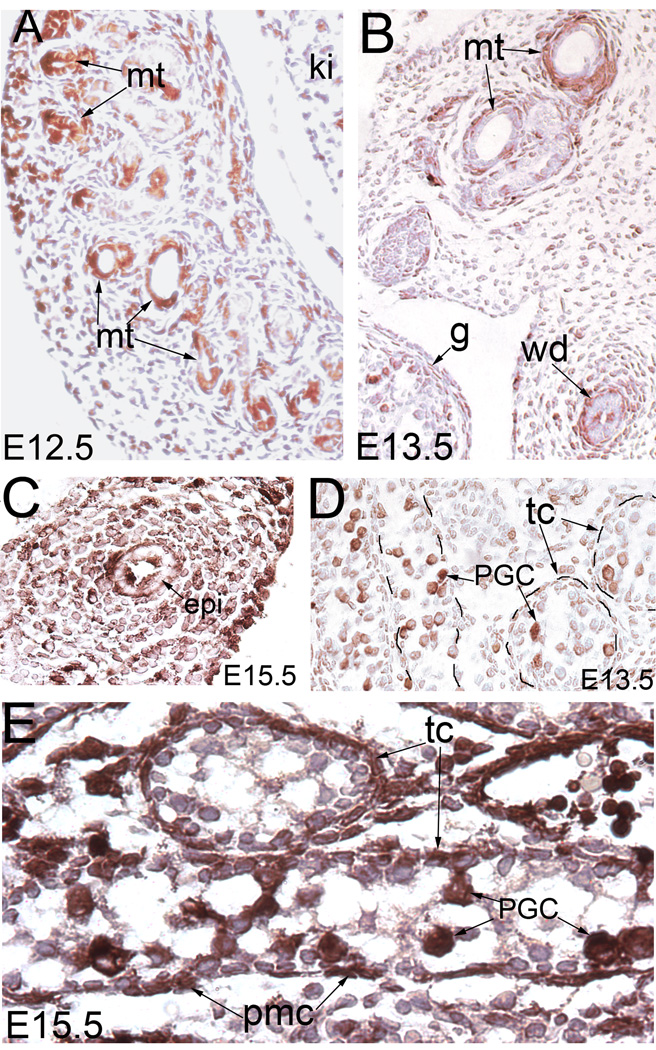

PC-2 expression was seen in the Wolffian duct and mesonephros in both mesenchyme and epithelium in human tissues (Chauvet et al., 2002). Here, we examined the spatiotemporal expression of Pkd2 during male reproductive system development by using an antibody for mouse PC-2. We detected PC-2 in the mesonephric tubules at E12.5 (Fig.1A), consistent with the stage of expresssion in a human tissue study (Chauvet et al., 2002). One day later, PC-2 expression was reduced in the epithelium but appeared in mesenchyme associated with the Wolffian duct and mesonephric tubules (Fig.1B, C). In the epithelial cells, it was seen in both luminal side and basal side (Fig.1B, C).

Figure 1. PC-2 staining in developing male reproductive system.

(A) PC-2 staining of the mesonephros at E12.5. (B) PC-2 staining of the mesonephros and the Wolffian duct at E13.5. (C) PC-2 staining of the epididymis. (D) PC-2 staining of E13.5 testis. (E) PC-2 staining of E15.5 testis. epi: epididymis; g: gonad; ki: kidney; mt: mesonephric tubules; PGC: primordial germ cells; pmc: peritubular myoid cell; tc: testicular cord; wd: Wolffian duct

PC-2 has been detected in the Sertoli cells and germ cells in the testicular cords during postnatal development (Markowitz et al., 1999). However, it is unknown if it is required for embryonic development of the testis. Here, we found that PC-2 was expressed in the PGCs of the E13.5 testis (Fig.1D). By E15.5, it was also seen in the interstitial cells of the testis (Fig.1E). Altogether, PC-2 showed dynamic expression in multiple tissues in the male reproductive system, suggestive of a developmental role.

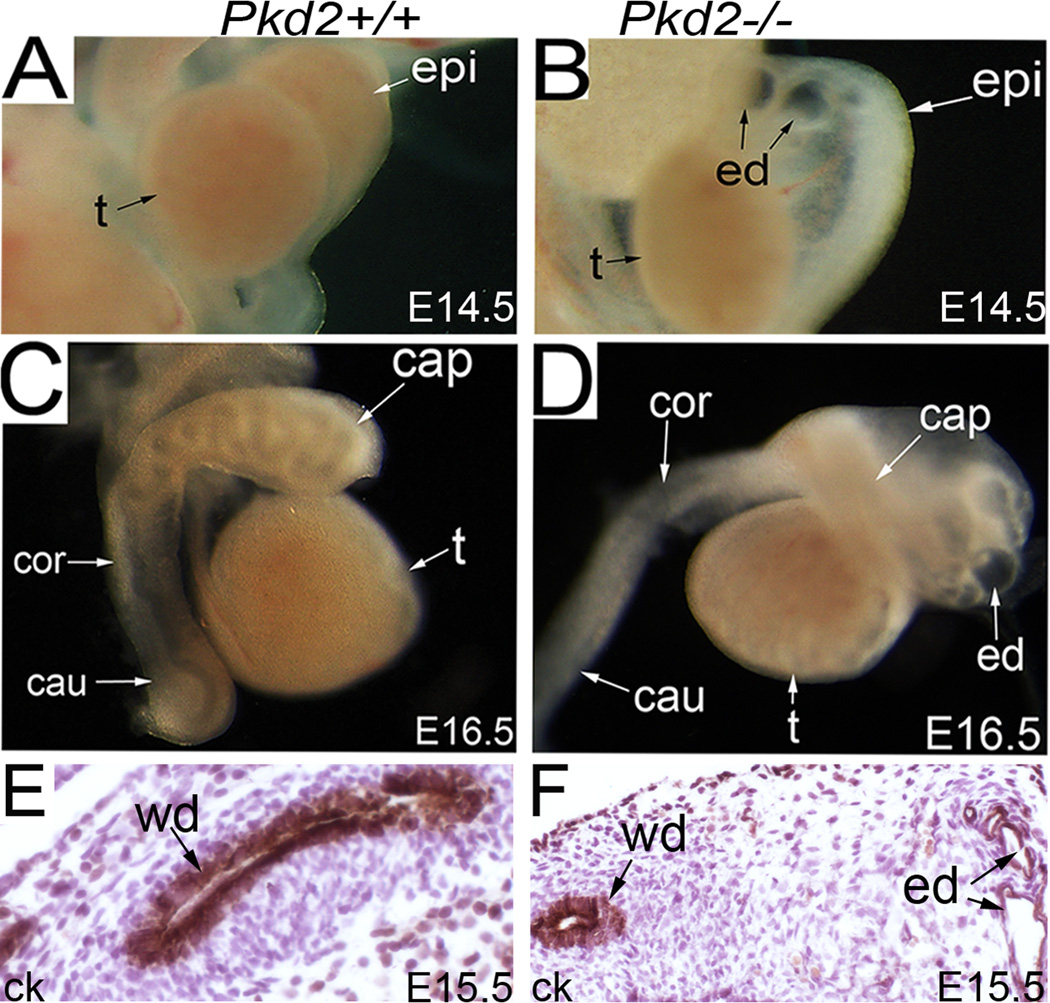

Male reproductive tract defects in Pkd2−/− mice

Next, we examined the male reproductive system in Pkd2−/− mice. Many of the Pkd2−/− mice died beginning at E13.5 to E16.5 with multiple organ system defects. The earliest defect in Pkd2−/− mice was mesonephric tubule/efferent duct dilation, which became evident at E13.5 to E15.5 (Fig.2A, B). The Wolffian ducts of mutant and control mice, labeled by pan-cytokeratin staining, were comparable at E15.5 (Fig.2E, F). At E16.5, defects in the epididymis in Pkd2−/− mice became evident (Fig.2C, D). The epididymal duct, derived from the Wolffian duct, started to coil in the caput segment of the wild-type epididymis at this time. By contrast, it remained straight in the mutant epididymis, indicating a delay in development (Fig.2C, D).

Figure 2. Male reproductive tract defects in Pkd2−/− mice.

(A, B) The male reproductive system at E14.5, showing efferent duct dilation in the mutant. (C, D) The male reproductive system at E16.5, showing severe dilation of the efferent ducts and coiling defect of the epididymal duct in the mutant. (E, F) Pan-cytokeratin staining of the Wolfian ducts at E15.5. cap: caput epididymis; cau: cauda epididymis; ck: pan-cytokeratin; cor: corpus epididymis; ed: efferent duct; epi: epididymis; t: testis

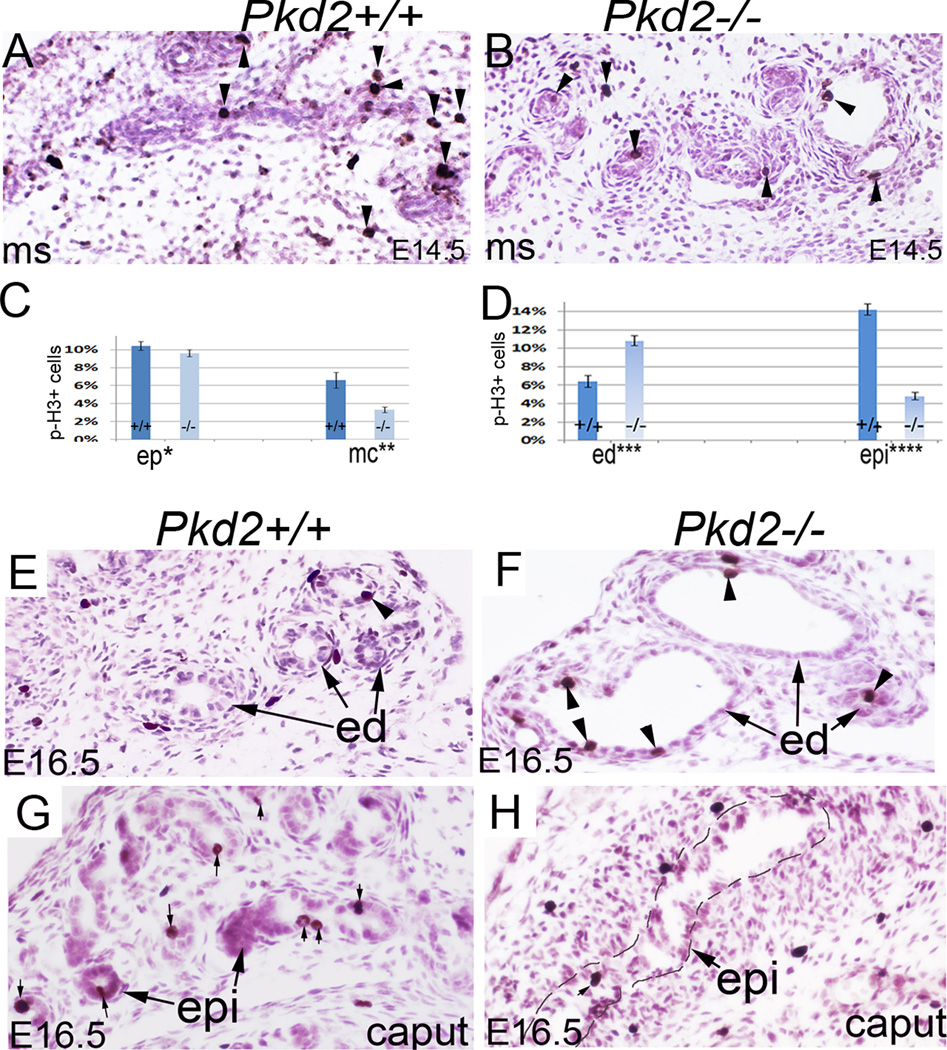

We performed apoptosis and proliferation assays in the male reproductive tract. Staining with an antibody for phospho-histone H3, a mitosis marker, showed that mitosis in E14.5 mesonephros was vigorous in both epithelium and mesenchyme in wild-type embryos but was reduced in mutant mesonephros, notably in the mesenchyme, suggesting that Pkd2 also regulates development of mesonephric mesenchyme (Fig.3A, B; C). At E16.5, mitosis in the efferent ducts was less in control mice compared to the earlier time point, but remained active in mutants (Fig.3D; E, F). In the epididymis, the mitotic ratio was significantly decreased in mutants compared to controls (Fig.3D; G, H). TUNEL staining failed to detect apoptosis in the efferent ducts and epididymis in both genotypes (data not shown). Altogether, these data suggest that Pkd2 plays an essential role in male reproductive tract development.

Figure 3. Proliferation analysis in the male reproductive tract.

(A, B) Phospho-histone H3 staining of E15.5 mesonephros. (C) Bar graphs represent mitotic ratios in the mesonephros. (D) Bar graphs represent mitotic ratios in the efferent ducts and caput epididymis. Data are expressed as mean and SEM. (E, F) Phospho-histone H3 staining of E16.5 efferent ducts, arrow heads indicate positive cells. (G, H) Phospho-histone H3 staining of the epididymides, arrows indicate positive cells. *non-significant, **P<0.01, *** P<0.01, ****P<0.01. cap: caput epididymis; ed: efferent duct; ep: epithelium; epi: epididymis; mc: mesenchyme; ms: mesonephros; p-H3: phospho-histone H3.

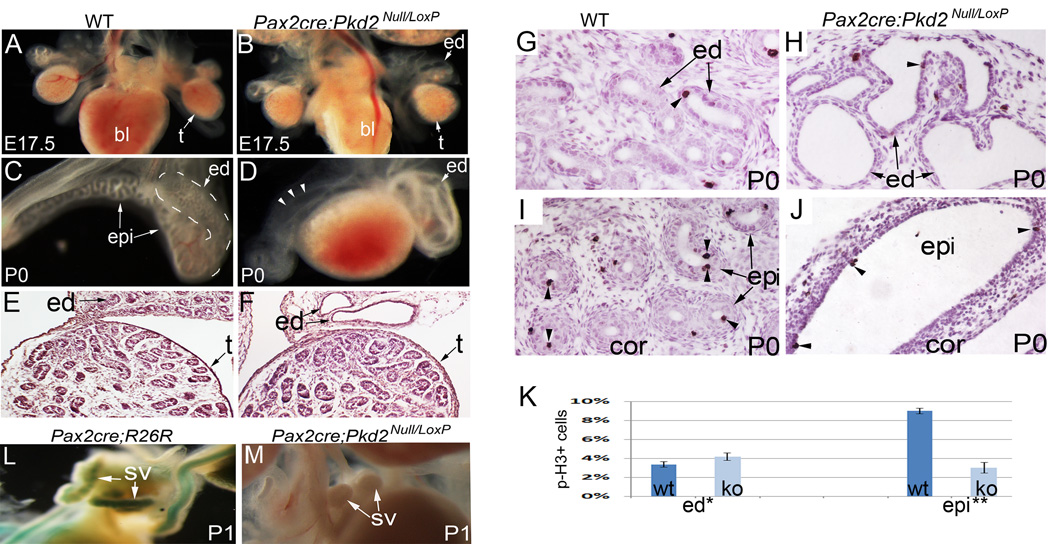

Epithelial-specific disruption of Pkd2 is sufficient to cause efferent duct dilation and epididymis coiling defect in the male reproductive tract

To dissect roles of Pkd2 in different cell types, we used Pax2-cre mice to specifically disrupt Pkd2 from epithelium of the male reproductive tract and examined male reproductive tract development in Pax2-cre; Pkd2 Null/Loxp conditional knockout mice. As has been shown in previous studies, Pax2-cre specifically targets epithelia of the reproductive tract, but has no effect on mesenchyme and the testis (Nie and Arend, 2013). Therefore, using this model, we could exclude a potential effect from testis defects present in Pkd2−/− mice. Pax2-cre; Pkd2 Null/Loxp mutant mice died in the first few days after birth with severe kidney dilation. In the reproductive tract, efferent duct dilation and lack of epididymal coiling in conditional knockout mice were similar to that seen in Pkd2−/− mice. Efferent duct dilation was first visible at E15.5 (data not shown), and became very severe at late gestation and postnatal stages (Fig.4A – F). Epithelial coiling events in the mutant epididymis were very few when examined at the newborn stage, whereas a highly coiled epithelial tube was seen in the control epididymis at this time (Fig.4C, D). Testis development in the mutants was comparable to that of wild-type controls until newborn stage, as indicated by normal histology and proper descent (Fig.4A, B; E, F).

Figure 4. Reproductive tract defects in Pax2-cre; Pkd2Null/Loxp mice.

(A, B) The male reproductive system at E17.5, showing efferent duct dilation. (C, D) The male reproductive system at P0, showing efferent duct dilation and coiling defect in the mutant. Mutant epididymis was also dilated as indicated by arrow heads. (E, F) Histology of the testes and efferent ducts at P0. (G, H) Phospho-histone3 staining of the efferent ducts. Arrow heads indicate mitotic cells. (I, J) Phospho-histone3 staining of the epididymides. Arrow heads indicate mitotic cells. (K) Bar graphs represent mitotic ratios in the efferent ducts and epididymides. (L, M) Delayed seminal vesicle development in the mutant mouse at P1. *: non-significant; **: P<0.01. bl: bladder; ed: efferent duct; epi: epididymis; ko: knockout mice; p-H3: phospho-histone H3; sv: seminal vesicle; t: testis; wt: wild type

Phospho-histone H3 staining showed that, in the efferent ducts, the mitotic ratios in mutants and controls were comparable at the newborn stage (Fig. 4G, H; K). In the epididymis, however, mitotic activity was very low in mutants but remained abundant in controls (Fig. 4I, J; K).

In postnatal stages, we also found a marked delay in seminal vesicle morphogenesis in mutant mice (Fig.4L. M). Normally, the seminal vesicle bud starts to elongate and branch during postnatal development. However, seminal vesicle development in mutants was arrested at the bud stage (Fig.4L, M). Collectively, these results show that epithelial expression of Pkd2 plays a pivotal role for male reproductive tract development.

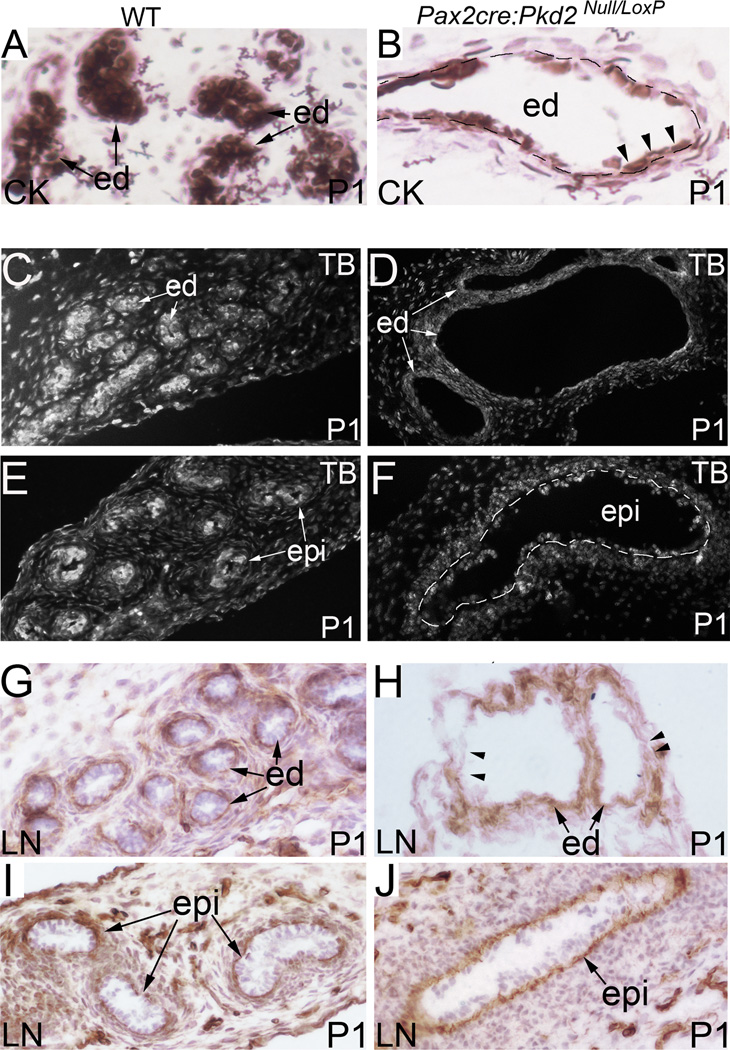

Epithelial deletion of Pkd2 causes changes in cellular phenotype and disrupts epithelial integrity in the male reproductive tract

The conditional knockout mouse model allows us to analyze reproductive tract development throughout embryogenesis and also during early postnatal development. We examined mutant epithelium with a set of molecular markers, including pan-cytokeratin, α-tubulin and laminin. During postnatal development, epithelial cells in the efferent ducts became flat rather than cuboidal, as highlighted by pan-cytokeratin staining (Fig.5A, B). Epithelial cells of cysts were often separated from one another, suggesting loss of cell-cell adhesions (Fig.5A, B). Cell shape change in Pkd2−/− epithelia suggests Pkd2 might be involved in regulating cytoskeleton dynamics. We examined tubulin cytoskeleton in the reproductive tract of Pax2-cre; Pkd2Null/Loxp mutant mice by immunostaining for α-tubulin, a subunit for microtubule assembling. We found that α-tubulin levels were reduced in the mutant efferent ducts and epididymis during postnatal development (Fig.5C, D; E, F). Changes in the basement membrane, visualized by laminin staining, were also detected in mutant epithelia (Fig.5G, H; I, J). Laminin staining in mutant mice showed thickened, layered and often discontinuous basement membranes (Fig.5H, J). Altogether, these results suggest that epithelial PC-2 plays an essential role in maintaining epithelial integrity.

Figure 5. Pan-cytokeratin, laminin and α-tubulin staining in the male reproductive tract of Pax2-cre; Pkd2 Null/Loxp mice.

(A, B) Pan-cytokeratin staining of the efferent ducts at P1. Cystic epithelium exhibits a flattened appearance rather than cuboidal in the mutant as indicated by arrow heads. (C, D) α- tubulin staining of the efferent ducts at P1. (E, F) α- tubulin staining of the epididymides at P1. (G, H) Laminin staining of the efferent ducts at P1. Arrow heads indicate areas lacking laminin staining. (I, J) Laminin staining of the epididymides at P1. CK: pan-cytokeratin; cor: corpus epididymis; ed: efferent duct; epi: epididymal epithelium; LN: laminin; TB: tubulin

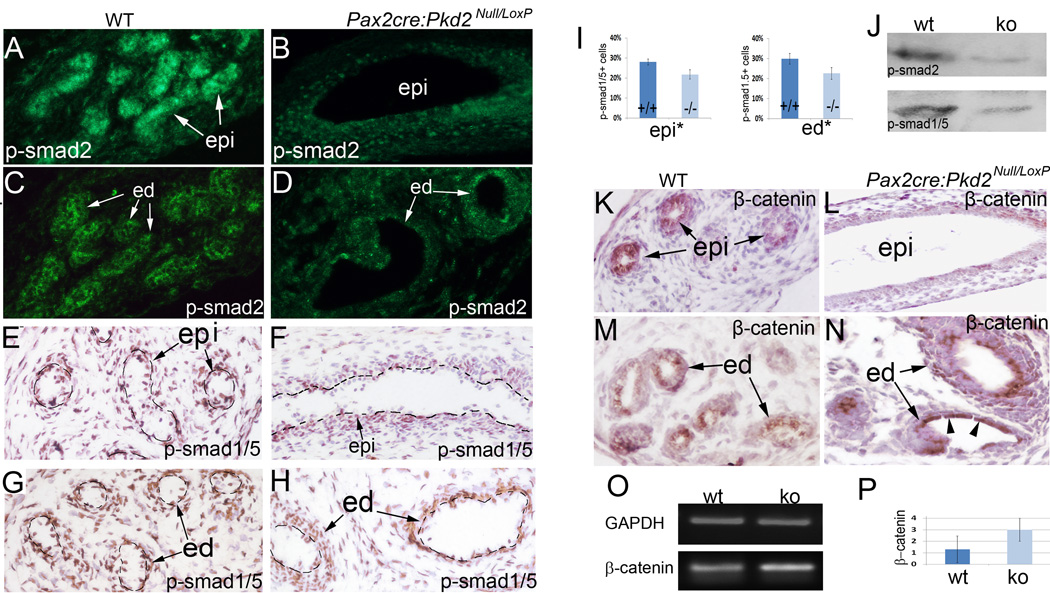

Epithelial-specific deletion of Pkd2 affects Tgf-β/Bmp and canonical Wnt signaling in the male reproductive tract

To gain a mechanistic understanding of the reproductive tract defects in PC-2 deficiency mice, we analyzed a set of developmental signaling pathways that are critical for male reproductive tract development. The Tgf-β/Bmp signaling pathways are critical for ductal system development in the male reproductive tract, and disrupting Tgf-β signaling abolishes epithelial coiling in the epididymis (Di Giovanni et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2004; Tomaszewski et al., 2007). We therefore tested if epithelial disruption of Pkd2 affects Tgf-β/Bmp signaling in the male reproductive tract by immunostaining for phospho-Smad2 and phospho-Smad1/5, which are intracellular mediators of Tgf-β and Bmp signaling respectively. Consistent with a previous study (Tomaszewski et al., 2007), the level of phospho-Smad2 was high in wild-type epididymal epithelium, indicative of high requirements of Tgf-β signaling by epithelial cells (Fig.6A). However, in mutant epididymal epithelium, the phospho-Smad2 level was visibly reduced beginning at late gestation, notably in the caput and corpus segments (Fig.6B and data not shown). Similarly, the level of phospho-Smad2 was reduced in the epithelium of mutant efferent ducts (Fig.6C, D). Staining for phospho-Smad1/5 was reduced, suggesting that Bmp signaling was also compromised (Fig.6E–I).These observations were further confirmed with western blot analysis (Fig.6J).

Figure 6. Altered intracellular signal transduction of Tgf-β/Bmp and canonical Wnt signaling in the male reproductive tract of Pax2-cre; Pkd2Null/Loxp mice.

(A, B) Immunofluorescence for phospho-Smad2 in the epididymides at P0. (C, D) Immunofluorescence for phospho-Smad2 in the efferent ducts at P0. (E, F) Immunohistochemistry for phospho-Smad1/5 in the epididymides at P0. (G, H) Immunohistochemistry for phospho-Smad1/5 in the efferent ducts at P0. (I) Bar graphs represents percentages of phospho-Smad1/5 positive cells in the epithelia. (J) Western Blot for phospho-Smad2 and phospho-Smad1/5 of the epididymides and efferent ducts at P0. (K, L) β-Catenin staining of the epididymides at E18.5. (M, N) β-Catenin staining of the efferent ducts at E18.5. Note, significant upregulation of β-Catenin in the flat cells, as indicated by arrow heads. (O) RT-PCR for β-Catenin in E18.5 efferent ducts. (P) Relative fold expression of β-Catenin in E18.5 efferent ducts by real-time qRT-PCR. * P<0.05, ** P<0.05. cor: corpus epididymis; ed: efferent duct; ko: knockout mice; epi: epididymis; wt: wild type

Wnt signaling is critical for development of the Wolffian duct and its derivatives, and upregulation of canonical Wnt signaling was found in polycystic kidney disease (Carroll et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2009; Lombardi et al., 2013). Here, we performed immunostaining for β-catenin, an essential intracellular mediator of canonical Wnt signaling, in the reproductive tract of Pax2-cre; Pkd2Null/Loxp mice. We found that β-catenin levels were dramatically reduced in the mutant epididymis, but significantly increased in the mutant efferent ducts (Fig.6K, L; M, N). In cystic ductal epithelial cells, increased β-catenin expression was consistently detected (Fig.5N). We further confirmed this observation by RT-PCR and real-time qRT-PCR assays (Fig.6O, P). Changes in β-catenin levels suggest Wnt signaling might be affected in mutant reproductive system. Altogether, these results suggest a link between PC-2 activity and critical developmental signaling pathways in the male reproductive tract.

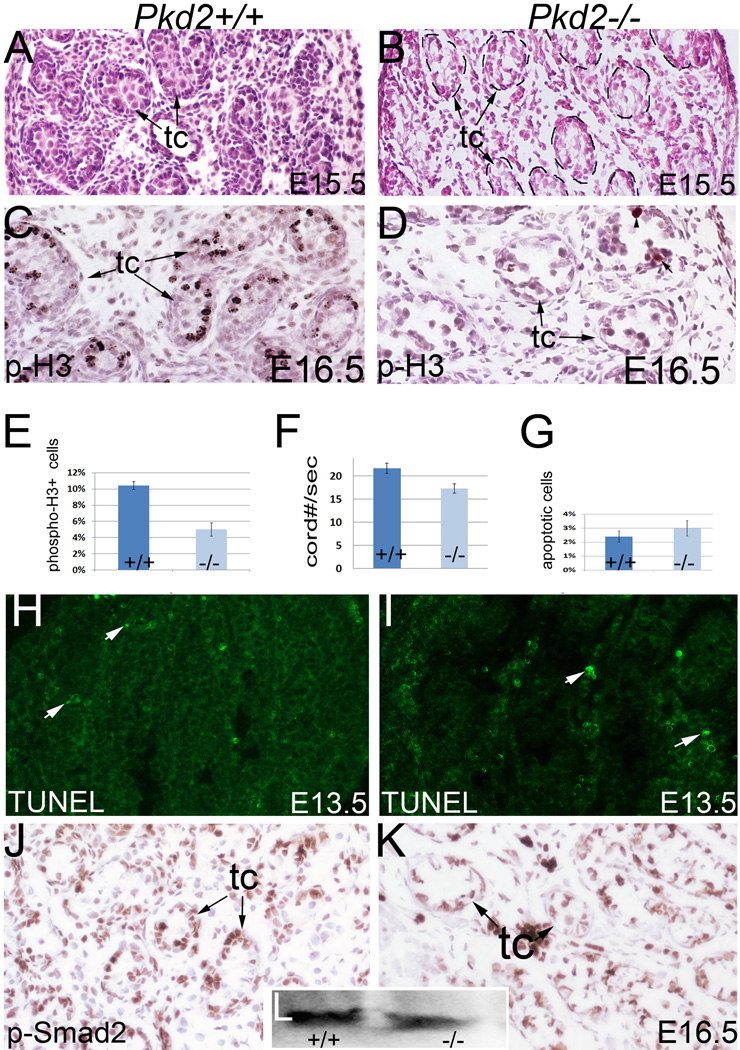

Testis defects in Pkd2−/− mice

As PC-2 also showed robust expression during gonadogenesis, we thus examined testis development in Pkd2−/− mice. Histologic examination at E15.5 revealed atypical testicular cord morphology in mutant mice (Fig.7A, B). We also detected a significant decrease in mitosis in the mutant testes at E16.5 with phospho-histone H3 staining (Fig.7C, D; E). In agreement with decreased cell proliferation, testicular cord growth was retarded in mutants as indicated by a decrease in the average number of testicular cords per section (Fig.7F). However, apoptosis assay by TUNEL staining did not reveal abnormal cell death in mutant testes at E13.5 and E16.5 (Fig.7G; H, I; and data not shown). We further examined Tgf-beta signaling by immunostaining for phospho-Smad2, which is critical for testicular cord growth (Itman et al., 2006; Miles et al., 2013). Phospho-Smad2 was detected at a high level in the testicular cords of the controls (Fig.7J). By contrast, the level of phospho-Smad2 was reduced in the mutant testicular cords (Fig.7K). This was confirmed with western blot (Fig.7L). Altogether, these results show that testicular defects exist in Pkd2−/− mice, and suggest that Pkd2 plays a role in testis development. However, the severity of testis defects varied in Pkd2−/− mice.

Figure 7. Testis development in Pkd2−/− mice.

(A, B) Histology of E15.5 testes. (C, D) Phospho-histone H3 staining of E16.5 testes. (E) Bar graphs represent mitotic ratios of the control and mutant testes (Mean ± SEM), P<0.05. (F) Bar graphs represent average numbers of testicular cords per section (Mean ± SEM), P<0.05. (G) Bar graphs represent ratios of apoptotic cells in the testes (Mean ± SEM). (H, I) TUNEL staining of E13.5 testes. (J, K) Phospho-Smad2 staining of the testes. (L) Western Blot for phospho-Smad2 of the testes. p-H3: phospho-histone H3; tc: testicular cord

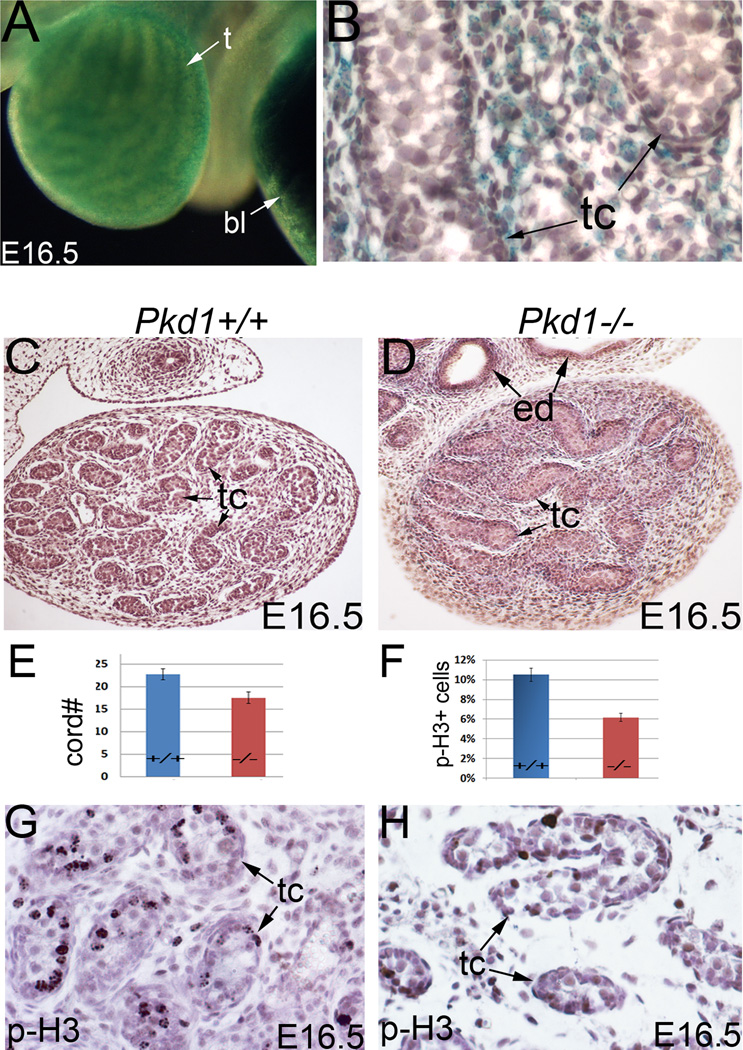

Here, we also describe the testicular phenotype of Pkd1−/− mice, which has not been previously described. We observed a high level of Pkd1 expression in the developing testes of Pkd1LacZ/+ mice at E15.5, as indicated by LacZ staining (Fig.8A). Pkd1 expression was primarily found in the interstitial cells including the peritubular myoid cells, but was undetectable or barely detectable within the testicular cords (Fig.8B). Testis morphology in Pkd1−/− mice was largely similar to that of Pkd2−/− mice. At E16.5, we found reduced interstitial tissue and a decrease in testicular cord growth (Fig.8C, D; E). This is further supported by decreased mitosis in Pkd1−/− testes (Fig.8F; G, H).

Figure 8. Pkd1 expression and testis development in Pkd1−/− mice.

(A) LacZ staining of Pkd1LacZ/+ testis at E16.5. (B) Section of LacZ-stained testis, showing widespread Pkd1 expression in the interstitium. (C, D) Histology of E16.5 testes. (E) Bar graphs represent average testicular cord numbers per section of each genotype (Mean ± SEM), P<0.05. (F) Bar graphs represent proliferation ratios (mean ± SEM), P<0.05. (G, H) Phospho-histone H3 staining of the testes. bl: bladder; ed: efferent duct; p-H3: phospho-histone H3; t: testis; tc: testicular cord

Discussion

This work demonstrates for the first time that Pkd2, like Pkd1 (Nie and Arend, 2013), is essential for male reproductive system development. Disruption of Pkd2 in mice causes efferent duct dilation, lack of epididymal coiling, and altered testicular development. Specific deletion of Pkd2 from the epithelium is sufficient to cause efferent duct and epididymis defects recapitulating those seen in Pkd2−/− mice, suggesting that epithelial expression of Pkd2 plays a critical role in maintaining epithelial integrity in the male reproductive tract. Our results also show that Pkd2 function is not critical for early tubulogenesis in the mesonephros but is essential for maintaining tubule integrity. Loss of Pkd2 induces phenotypic changes in epithelial cells and basement membrane malformation in the efferent ducts, and altered signaling in epithelial cells. Elevated β-catenin is a key feature of Pkd2-null epithelial cells of the efferent ducts, which explains increased epithelial cell proliferation in mutant efferent ducts.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that ADPKD genes regulate cell proliferation (Aguiari et al., 2008; Nishio et al., 2005). It has been proposed that increased cell proliferation induced by ADPKD gene mutations is an important mechanism for cyst formation in the kidney (Chapin and Caplan, 2010; Hanaoka and Guggino, 2000; Wilson, 2004). In the male reproductive system, however, we detected contrasting effects of Pkd2 on mitosis in different tissues. While loss of Pkd2 did not limit cell proliferation in the developing efferent ducts, it slowed proliferation in the epididymis and testis. In the epididymis, epithelial cell proliferation is controlled by testosterone signaling from the testis, which is further relayed by local mesenchymal signaling (Cooke et al., 1991; Cornwall, 2009; Tomaszewski et al., 2007). Our data suggest that PC-2 activity is critical for maintaining the testosterone signaling cascade by linking to developmental signaling pathways that control epithelial development. Indeed, deficiency of PC-2 impaired both Tgf-β and Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathways in the epididymis, which are essential for epithelial development (Di Giovanni et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2004; Lombardi et al., 2013; Tomaszewski et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2001). Altogether, these data suggest that the functions of Pkd2 for cell signaling and proliferation depend on a specific developmental context.

How PC-2 activity regulates these developmental pathways remains to be determined at the molecular level. Besides an established role in regulating calcium influx, PC-2 also regulates cytoskeletal dynamics. It has been shown that PC-2 is involved in actin-cytoskeleton regulation via interaction with Hax-1 (Gallagher et al., 2000). Here, we show PC-2 activity is also important for maintenance of tubulin, an essential component for microtubule assembly. One possible mechanism is that PC-2 regulates developmental signaling through maintaining the microtubules. Indeed, a recent study showed that microtubule function is critical for Tgf-β signaling in a developmental process (Kitase and Shuler, 2013). Microtubules are also the cytoskeleton for the cilium, an organelle important for cell function in a physiological setting. Microtubule reduction also indicates that cilia might change in Pkd2 mutant epithelia. Overall, the reproductive tract phenotype of Pkd2−/− mice is largely similar to that of Pkd1−/− mice, suggesting that PC-2 and PC-1 may regulate common cellular activities during ductal system development of the male reproductive system (Nie and Arend, 2013).

In this work, we also revealed novel roles of Pkd2 and Pkd1 in testicular development. We found high levels of Pkd1 and Pkd2 expression in testicular interstitial tissue, and detected altered testis development in Pkd1 and Pkd2 null mice. Besides decreased interstitial cell numbers, the function of the interstitial cells might also be impaired in mutant mice, given the altered levels of phospho-Smad2 and phospho-Smad1/5. These changes may explain delayed development of the testicular cords in the mutant mice. In addition, we also detected robust expression of PC-2 in PGCs during cord morphogenesis, which is not found for Pkd1/PC-1. Pkd2 is important for germ cell maturation and motility (Gao et al., 2003). However, the functional role of Pkd2 in early PGC development remains to be elucidated. It is possible that PC-2 is involved in PGC clustering and proper colonization in the testicular cords, as we often saw abnormal histology of testicular cords in Pkd2−/− mice.

Finally, we also found that Pkd2 is required for normal seminal vesicle development. Seminal vesicle cysts are the most common finding among the reproductive tract cysts in ADPKD patients (Belet et al., 2002; Danaci et al., 1998). Therefore, PKD genes are likely critical for both development and maintenance of the seminal vesicles. The only reproductive organ that did not show obvious defects in PC-2 deficient mice was the vas deferens. It also should be noted that the male reproductive system continues to develop and mature until puberty. Maintenance of reproductive organs may also require PKD genes in adulthood. An inducible knockout system may prove useful to address complex roles of PKD genes in maturation and/or maintenance of the adult male reproductive system.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a generous donation from the Lillian Goldman Charitable Trust. This study utilized resources provided by the NIDDK sponsored Johns Hopkins Polycystic Kidney Disease Research and Clinical Core Center (P30 DK090868). We are grateful to Dr Timothy H. Moran of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for use of the microscope and imaging system. We thank Dr Andy Groves at the Baylor College of Medicine and Dr Angelika Doetzlhofer of the Department of Neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for providing Pax2-cre mice.

Abbreviations

- ADPKD

autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- PC-1

polycystin-1

- PC-2

polycystin-2

- PGC

primordial germ cell

- PKD

polycystic kidney disease

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

Authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aguiari G, Trimi V, Bogo M, Mangolini A, Szabadkai G, Pinton P, Witzgall R, Harris PC, Borea PA, Rizzuto R, del Senno L. Novel role for polycystin-1 in modulating cell proliferation through calcium oscillations in kidney cells. Cell proliferation. 2008;41:554–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataille S, Demoulin N, Devuyst O, Audrezet MP, Dahan K, Godin M, Fontes M, Pirson Y, Burtey S. Association of PKD2 (polycystin 2) mutations with left-right laterality defects. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;58:456–460. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belet U, Danaci M, Sarikaya S, Odabas F, Utas C, Tokgoz B, Sezer T, Turgut T, Erdogan N, Akpolat T. Prevalence of epididymal, seminal vesicle, prostate, and testicular cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Urology. 2002;60:138–141. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01612-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhunia AK, Piontek K, Boletta A, Liu L, Qian F, Xu PN, Germino FJ, Germino GG. PKD1 induces p21(waf1) and regulation of the cell cycle via direct activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway in a process requiring PKD2. Cell. 2002;109:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan J, Capel B. One tissue, two fates: molecular genetic events that underlie testis versus ovary development. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2004;5:509–521. doi: 10.1038/nrg1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Maeda Y, Cedzich A, Torres VE, Wu G, Hayashi T, Mochizuki T, Park JH, Witzgall R, Somlo S. Identification and characterization of polycystin-2, the PKD2 gene product. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:28557–28565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP. Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Developmental cell. 2005;9:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casuscelli J, Schmidt S, DeGray B, Petri ET, Celic A, Folta-Stogniew E, Ehrlich BE, Boggon TJ. Analysis of the cytoplasmic interaction between polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2009;297:F1310–F1315. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00412.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin HC, Caplan MJ. The cell biology of polycystic kidney disease. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;191:701–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvet V, Qian F, Boute N, Cai Y, Phakdeekitacharoen B, Onuchic LF, Attie-Bitach T, Guicharnaud L, Devuyst O, Germino GG, Gubler MC. Expression of PKD1 and PKD2 transcripts and proteins in human embryo and during normal kidney development. The American journal of pathology. 2002;160:973–983. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64919-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes AN, Wilhelm D, Davidson T, Dejana E, Harley V, Sinclair A, Koopman P. Endothelial cell migration directs testis cord formation. Developmental biology. 2009;326:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke PS, Young P, Cunha GR. Androgen receptor expression in developing male reproductive organs. Endocrinology. 1991;128:2867–2873. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-6-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall GA. New insights into epididymal biology and function. Human reproduction update. 2009;15:213–227. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmn055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaci M, Akpolat T, Bastemir M, Sarikaya S, Akan H, Selcuk MB, Cengiz K. The prevalence of seminal vesicle cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 1998;13:2825–2828. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.11.2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni V, Alday A, Chi L, Mishina Y, Rosenblum ND. Alk3 controls nephron number and androgen production via lineage-specific effects in intermediate mesoderm. Development. 2011;138:2717–2727. doi: 10.1242/dev.059030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher AR, Cedzich A, Gretz N, Somlo S, Witzgall R. The polycystic kidney disease protein PKD2 interacts with Hax-1, a protein associated with the actin cytoskeleton. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:4017–4022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z, Ruden DM, Lu X. PKD2 cation channel is required for directional sperm movement and male fertility. Current biology : CB. 2003;13:2175–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Outeda P, Zhou Q, Zhou F, Menezes LF, Qian F, Huso DL, Germino GG, Piontek KB, Watnick T. Pkd1 and Pkd2 are required for normal placental development. PloS one. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert-Sirieix M, Makoukji J, Kimura S, Talbot M, Caillou B, Massaad C, Massaad-Massade L. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway is a direct enhancer of thyroid transcription factor-1 in human papillary thyroid carcinoma cells. PloS one. 2011;6:e22280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Perrett S, Kim K, Ibarra C, Damiano AE, Zotta E, Batelli M, Harris PC, Reisin IL, Arnaout MA, Cantiello HF. Polycystin-2, the protein mutated in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), is a Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:1182–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaoka K, Guggino WB. cAMP regulates cell proliferation and cyst formation in autosomal polycystic kidney disease cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2000;11:1179–1187. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1171179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannema SE, Hughes IA. Regulation of Wolffian duct development. Hormone research. 2007;67:142–151. doi: 10.1159/000096644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpin A, Schartl M. Sex determination: switch and suppress. Current biology : CB. 2011;21:R656–R659. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Chen YX, Wang D, Qi X, Li TG, Hao J, Mishina Y, Garbers DL, Zhao GQ. Developmental expression and function of Bmp4 in spermatogenesis and in maintaining epididymal integrity. Developmental biology. 2004;276:158–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itman C, Mendis S, Barakat B, Loveland KL. All in the family: TGF-beta family action in testis development. Reproduction. 2006;132:233–246. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A, Yao H, Hinton BT. Development and morphogenesis of the Wolffian/epididymal duct, more twists and turns. Developmental biology. 2009;325:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagarajah P, Ayyathurai R, Lynne CM. Male infertility and adult polycystic kidney disease - revisited: case report and current literature review. Andrologia. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2011.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl J, Capel B. Sertoli cells of the mouse testis originate from the coelomic epithelium. Developmental biology. 1998;203:323–333. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Ding T, Fu Y, Li C, Cui L, Li A, Lian P, Liang D, Wang DW, Guo C, Ma J, Zhao P, Coffey RJ, Zhan Q, Wu G. Conditional mutation of Pkd2 causes cystogenesis and upregulates beta-catenin. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:2556–2569. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009030271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitase Y, Shuler CF. Microtubule disassembly prevents palatal fusion and alters regulation of the E-cadherin/catenin complex. The International journal of developmental biology. 2013;57:55–60. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.120117yk. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Cai Y, Geng L, Maeda Y, Nishimura S, Witzgall R, Ehrlich BE, Somlo S. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nature cell biology. 2002;4:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi AP, Royer C, Pisolato R, Cavalcanti FN, Lucas TF, Lazari MF, Porto CS. Physiopathological aspects of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in the male reproductive system. Spermatogenesis. 2013;3:e23181. doi: 10.4161/spmg.23181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manno M, Marchesan E, Tomei F, Cicutto D, Maruzzi D, Maieron A, Turco A. Polycystic kidney disease and infertility: case report and literature review. Archivio italiano di urologia, andrologia : organo ufficiale [di] Societa italiana di ecografia urologica e nefrologica / Associazione ricerche in urologia. 2005;77:25–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz GS, Cai Y, Li L, Wu G, Ward LC, Somlo S, D'Agati VD. Polycystin-2 expression is developmentally regulated. The American journal of physiology. 1999;277:F17–F25. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.277.1.F17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martineau J, Nordqvist K, Tilmann C, Lovell-Badge R, Capel B. Male-specific cell migration into the developing gonad. Current biology : CB. 1997;7:958–968. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles DC, Wakeling SI, Stringer JM, van den Bergen JA, Wilhelm D, Sinclair AH, Western PS. Signaling through the TGF beta-activin receptors ALK4/5/7 regulates testis formation and male germ cell development. PloS one. 2013;8:e54606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux K, Wylie C. Primordial germ cell migration. The International journal of developmental biology. 2004;48:537–544. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041833km. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie X, Arend LJ. Pkd1 is required for male reproductive tract development. Mechanisms of development. 2013;130:567–576. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishio S, Hatano M, Nagata M, Horie S, Koike T, Tokuhisa T, Mochizuki T. Pkd1 regulates immortalized proliferation of renal tubular epithelial cells through p53 induction and JNK activation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:910–918. doi: 10.1172/JCI22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama T, Groves AK. Generation of Pax2-Cre mice by modification of a Pax2 bacterial artificial chromosome. Genesis. 2004;38:195–199. doi: 10.1002/gene.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Germino FJ, Cai Y, Zhang X, Somlo S, Germino GG. PKD1 interacts with PKD2 through a probable coiled-coil domain. Nature genetics. 1997;16:179–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewski J, Joseph A, Archambeault D, Yao HH. Essential roles of inhibin beta A in mouse epididymal coiling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:11322–11327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703445104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torra R, Sarquella J, Calabia J, Marti J, Ars E, Fernandez-Llama P, Ballarin J. Prevalence of cysts in seminal tract and abnormal semen parameters in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2008;3:790–793. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05311107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiokas L, Kim S, Ong EC. Cell biology of polycystin-2. Cellular signalling. 2007;19:444–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora N, Perrone R, Bianchi DW. Reproductive issues for adults with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2008;51:307–318. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PD. Polycystin: new aspects of structure, function, and regulation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2001;12:834–845. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V124834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PD. Polycystic kidney disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:151–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Markowitz GS, Li L, D'Agati VD, Factor SM, Geng L, Tibara S, Tuchman J, Cai Y, Park JH, van Adelsberg J, Hou H, Jr, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W, Somlo S. Cardiac defects and renal failure in mice with targeted mutations in Pkd2. Nature genetics. 2000;24:75–78. doi: 10.1038/71724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu GM, Gonzalez-Perrett S, Essafi M, Timpanaro GA, Montalbetti N, Arnaout MA, Cantiello HF. Polycystin-1 activates and stabilizes the polycystin-2 channel. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:1457–1462. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2002;13:2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiba S, Shiratori H, Kuo IY, Kawasumi A, Shinohara K, Nonaka S, Asai Y, Sasaki G, Belo JA, Sasaki H, Nakai J, Dworniczak B, Ehrlich BE, Pennekamp P, Hamada H. Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science. 2012;338:226–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1222538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Chen YX, Liu XM, Xu Z, Qi X. Mutation in Bmp7 exacerbates the phenotype of Bmp8a mutants in spermatogenesis and epididymis. Developmental biology. 2001;240:212–222. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]