Abstract

Objective

To explore whether the increased risk of preterm birth following treatment for cervical disease is limited to the first birth following colposcopy.

Design

Nested case–control study.

Setting

Twelve NHS hospitals in England.

Population

All nonmultiple births from women selected as cases or controls from a cohort of women with both colposcopy and a hospital birth. Cases had a preterm (20–36 weeks of gestation) birth. Controls had a term birth (38–42 weeks) and no preterm.

Methods

Obstetric, colposcopy and pathology details were obtained.

Main outcome measures

Adjusted odds ratio of preterm birth in first and second or subsequent births following treatment for cervical disease.

Results

A total of 2798 births (1021 preterm) from 2001 women were included in the analysis. The risk of preterm birth increased with increasing depth of treatment among first births post treatment [trend per category increase in depth, categories <10 mm, 10–14 mm, 15–19 mm, ≥20 mm: odds ratio (OR) 1.23, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.12–1.36, P < 0.001] and among second and subsequent births post treatment (trend OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.15–1.56, P < 0.001). No trend was observed among births before colposcopy (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.83–1.16, P = 0.855). The absolute risk of a preterm birth following deep treatments (≥15 mm) was 6.5% among births before colposcopy, 18.9% among first births and 17.2% among second and subsequent births post treatment. Risk of preterm birth (once depth was accounted for) did not differ when comparing first births post colposcopy with second and subsequent births post colposcopy (adjusted OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.89–1.49).

Conclusions

The increased risk of preterm birth following treatment for cervical disease is not restricted to the first birth post colposcopy; it remains for second and subsequent births. These results suggest that once a woman has a deep treatment she remains at higher risk of a preterm birth throughout her reproductive life.

Tweetable abstract

Risk of preterm birth following large treatments for cervical disease remains for second and subsequent births.

Keywords: Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, conisation, large loop excision of the transformation zone, preterm delivery

Introduction

Over the past decade there has been growing interest in the relationship between treatment for cervical disease and subsequent risk of preterm birth. Current published evidence is sufficient to establish that women who attend colposcopy are at a higher risk of a subsequent preterm birth (regardless of whether or not they are treated).1, 2 This suggests that some risk factors for cervical disease are similar to those for preterm birth. The risk is greater still among those who receive an excisional treatment at colposcopy.3 It is particularly high when the depth of the tissue excised is ≥15 mm.4, 5, 6

The majority of the literature has analysed only the first birth following the excisional treatment for each woman and usually compares the first birth post treatment with births before treatment. A few have compared all births post treatment with all births before treatment7, 8 and found no difference in risk between the first birth post treatment and all births post treatment. None of the published literature has formally investigated whether the effect of depth of excision on the risk of preterm birth changes with the number of births since the excision.

Here we explore whether the increased risk of preterm birth with increasing depth of excision is limited to the first birth following colposcopy or whether it remains increased for the second and subsequent births after excision of cervical disease.

Methods

Subjects

Women with cervical histology between April 1988 and December 2011 were identified from clinical records in 12 National Health Service (NHS) hospitals. They were linked using their NHS number (a unique identifier) and date of birth by Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) to hospital obstetric records between April 1998 and March 2011 for the whole of England. HES is a data warehouse containing details of all admissions to NHS hospitals in England.9 Obtaining colposcopy and pathology details was the most labour intensive part of the data collection process and many of the women who attended colposcopy had no births, so we designed the study in two phases. From the cohort (defined above) we identified women who had at least one singleton live birth with a gestational age of between 20 and 42 weeks. We then selected the first singleton preterm birth (gestational age 20–36 completed weeks) in each woman and frequency matched these to singleton term births (38–42 completed weeks) in women with no preterm births, forming the nested case–control data set. Births at 37 weeks of gestation, although considered early term,10 were not selected as controls to allow a clear divide between term and preterm births. Frequency matching was carried out using strata formed from maternal age at birth, parity, study site and whether the birth occurred before or after the first colposcopy, to ensure similar characteristics among women with term and preterm births. The matching was carried out on one birth per woman, in this study we refer to that birth as the ‘index birth’. As we include all singleton births from women selected as cases or controls in this analysis, the matching has been broken; therefore variables on which the original matching was performed are adjusted for in analyses. Full details on the study design have been published previously.2, 6

From HES records we obtained detailed obstetric information including: month and year of each birth, birthweight, whether the birth was a normal vaginal delivery or caesarean section, the mode of onset of labour (spontaneous versus induced), parity, overall index of multiple deprivation at the time of delivery, plus any (other) inpatient diagnoses or operations recorded for the mother. Hospitals entered colposcopy details into a study database and submitted anonymised pathology reports to Barts Health NHS Trust. Pathology reports were entered into the study database by two trained individuals (AP and TP) to ensure that measurements were entered in a standardised way, facilitating the identification of the length, width and depth of specimens. Individuals searching for and coding colposcopy information were blind to the case–control status of the women.

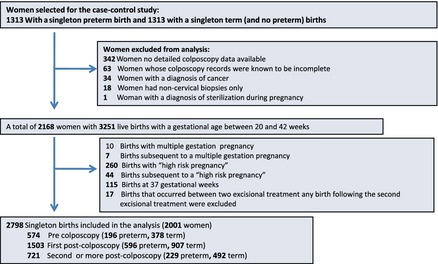

Women were excluded from analysis if detailed colposcopy information was not available (n = 342), if colposcopy records were known to be incomplete (n = 63), if the only pathology sample reported was noncervical (n = 18) and if the woman was diagnosed with cervical cancer at any time (n = 34). We also excluded one woman who was recorded as being sterilised while pregnant (Figure 1). This left 2168 women with a total of 3251 live births with a gestational age between 20 and 42 weeks.

Figure 1.

Inclusions and exclusions from the study.

For the main analysis we further excluded births with a gestational age of 37 weeks (siblings of index births, n = 115), births from pregnancies with multiple fetuses (n = 10) and births from a ‘high‐risk’ pregnancy (n = 260), together with 51 births subsequent to multiple or high‐risk pregnancies under the assumption that these births would have a particularly high risk of being preterm. Additionally, when births occurred between two excisional treatments, any births following the second excisional treatment were excluded (n = 17). Our definition of ‘high‐risk’ pregnancy (see ICD 10 diagnostic codes in Table S1) includes: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, placenta praevia with haemorrhage, supervision of high‐risk pregnancy, mental disorders and diseases of the nervous system complicating pregnancy and childbirth and the puerperium. All births for a woman were excluded if they had an ICD 10 diagnostic code of diabetes, hypertension or morbid obesity at any time, for all other diagnostic codes only the birth associated with that code and any subsequent births were excluded. As our previous publication6 was restricted to births after colposcopy, this study includes an extra 397 women with a birth before colposcopy as well as six extra women who had at least one nonindex birth that was eligible for this study.

Births at 20–36 weeks of gestation were considered preterm, those at 20–31 weeks of gestation were considered very preterm. We define excisional treatment as: large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), laser excision, nonspecified cone excision or knife cone biopsy.

The main exposure of interest was depth of excision before birth, defined as the distance from the distal or external margin to the proximal or internal margin of the excised specimen.11 In all participating laboratories it was standard to report the depth as the last of three measurements, whereas the reporting of the other two measurements was arbitrary. When the excision was piecemeal, the largest fragment depth was used. For women with more than one excisional treatment the depths were summed. Sensitivity analyses for piecemeal excisions in this cohort have been described previously.6

We defined three time periods to classify births in relation to colposcopy: birth before colposcopy, first birth post colposcopy and second or subsequent birth post colposcopy. Births were classified into one of these periods, before exclusions were applied. For example if a woman had two births post colposcopy and the first one had a gestational age of 37 weeks, the second birth would still be classified as second or subsequent birth post colposcopy.

Statistical methods

Unconditional logistic regression was carried out to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All analyses were adjusted for the matching variables, namely study site and maternal age at birth, as well as potential confounders age at colposcopic treatment (or punch biopsy if not treated) and socio‐economic status (using the index of multiple deprivation in national quintiles). When more than one birth per mother was included we accounted for this clustering through the use of a clustered sandwich estimator for calculating standard errors. For the main analysis the model was run separately for each timing category (births before colposcopy, first births after colposcopy and second and subsequent births after colposcopy).

Absolute risks for the punch biopsy category were taken as the crude rates of preterm births observed in the cohort for women recorded as having a punch biopsy at their first colposcopy separately for births before colposcopy, first births after colposcopy and second and subsequent births after colposcopy. Absolute risks for the depth categories were calculated by combining the absolute risk for women who had a punch biopsy with the odds ratio for each depth category (relative to punch biopsy as the baseline).

Depth of excision was categorised as per the prespecified statistical analysis plan: excision with a depth <10 mm (small), 10–14 mm (medium),15–19 mm (large) and ≥20 mm (very large), as well as separate categories for excisional treatments with unknown depth and punch biopsy only (i.e. no excisional treatment). For the descriptive analyses, Cuzick's test12 for trend was carried out to test for trends between ordered categorical variables and depth of excision (excluding births before excision and excisions with unknown depth). For the continuous variables a linear regression model was used to test for trend.

The main analyses compared term births with all preterm births included in the study. We also carried out eight sensitivity analyses: (i) restricted to preterm births with a spontaneous onset of labour (in an attempt to exclude medically indicated preterm births); (ii) restricting preterm births to those that were very preterm; (iii) excluding all births following a caesarean section to test whether having a vaginal birth increased the trauma to the cervix and therefore increased the risk of preterm birth; (iv) restricting analyses to index births, to assess the effect on the results of introducing all other births in these women; (v) including in the analyses births at 37 weeks of gestation (in women with an index birth) as term births; (vi) excluding any births following the first preterm birth, to exclude excess risk of a subsequent (second) preterm birth; (vii) same as the previous analysis but restricted to birth with a spontaneous onset of labour; and viii) restricted to spontaneous and very preterm births.

Trends were calculated by excluding punch biopsies and treatments with unknown depths, and considering depth of treatment as a continuous variable from 1 (small) to 4 (very deep) in an unconditional logistic regression model, adjusted as in the models above. Interaction terms were used to test whether the effect of depth of excision differed between the three timing categories. Note that the trend and interaction odds ratios are roughly the factor by which the risk of preterm birth increases for each 5‐mm increase in depth of excision (beyond 7 mm) in one group relative to another. An interaction odds ratio of 1.0 would imply that the trend with depth of excision was the same in both groups.

Analyses were carried out in stata 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 2798 births (1021 preterm) from 2001 women were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Similar characteristics were observed among births included in the cohort and those included in the nested case–control study (Table S2). Characteristics of births included in the study by depth of excisional treatment are presented in Table 1. There was no difference in the distribution of these characteristics with the exception of an increasing proportion of preterm births as the depth of excisional treatment increases, which is reflected in the birthweight distribution. Although there is a statistically significant increase in maternal age at delivery with depth of excision, the increase is not clinically significant (with less than a year difference in age between those with small and those with very large excisions).

Table 1.

Characteristics of births included in the study by depth of excisional treatment

| No excisional treatment before birth | Small excision before birth | Medium excision before birth | Large excision before birth | Very large excision before birth | Unknown depth of excision before birth | Trenda P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of births | 1247 | 563 | 555 | 176 | 101 | 156 | |

| No. preterm births | 420 | 188 | 213 | 87 | 57 | 56 | |

| No. of women | 1105 | 433 | 404 | 138 | 82 | 119 | |

| Age at treatment | |||||||

| Mean age at treatment, years (SD) | 27.6 (5.3) | 26.8 (4.3) | 26.6 (4.3) | 27.0 (4.0) | 26.7 (3.8) | 27.2 (4.3) | 0.989 |

| Age at birth | |||||||

| Mean age at delivery, years (SD) | 29.3 (5.5) | 32.0 (4.4) | 31.9 (4.8) | 32.7 (4.4) | 32.8 (4.4) | 32.0 (4.5) | 0.032 |

| Birthweight, n (%) | |||||||

| < 2500 g | 277 (22) | 115 (21) | 132 (24) | 55 (31) | 39 (39) | 33 (21) | <0.001 |

| 2500–3499 g | 603 (49) | 263 (47) | 264 (48) | 77 (44) | 41 (41) | 76 (49) | |

| 3500–3999 g | 252 (20) | 131 (24) | 117 (21) | 31 (18) | 9 (9) | 31 (20) | |

| ≥4000 g | 104 (8) | 47 (8) | 39 (7) | 13 (7) | 10 (10) | 16 (10) | |

| Missing | 11 | 7 | 3 | – | 2 | – | |

| Parity, n (%) | |||||||

| None | 702 (56) | 262 (47) | 212 (38) | 79 (45) | 45 (45) | 66 (42) | 0.156 |

| 1 | 283 (23) | 176 (31) | 166 (30) | 50 (28) | 28 (28) | 55 (35) | |

| 2 | 121 (10) | 62 (11) | 84 (15) | 20 (11) | 16 (16) | 19 (12) | |

| ≥3 | 141 (11) | 63 (11) | 93 (17) | 27 (15) | 12 (12) | 16 (10) | |

| Birth order, n (%) | |||||||

| Birth before colposcopy | 574 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| First birth after colposcopy | 464 (69) | 391 (69) | 352 (63) | 120 (68) | 72 (71) | 104 (67) | 0.849 |

| Second or more birth after colposcopy | 209 (31) | 172 (31) | 203 (37) | 56 (32) | 29 (29) | 52 (33) | |

| Deprivation (in quintiles), n (%) | |||||||

| 1 (most deprived) | 459 (37) | 153 (27) | 173 (31) | 57 (32) | 28 (28) | 45 (29) | 0.133 |

| 2 | 325 (26) | 137 (24) | 134 (24) | 48 (27) | 30 (30) | 36 (23) | |

| 3 | 219 (18) | 128 (23) | 112 (20) | 39 (22) | 18 (18) | 36 (23) | |

| 4 | 136 (11) | 100 (18) | 78 (14) | 20 (11) | 19 (19) | 18 (12) | |

| 5 (least deprived) | 107 (9) | 43 (8) | 58 (10) | 12 (7) | 6 (6) | 21 (13) | |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – | |

Linear trend with increasing depth category from small (1) to very large (4) for births after colposcopy.

The adjusted odds ratio of preterm birth by depth of procedure at colposcopy stratified by timing of colposcopy in relation to the birth is presented in Table 2. The odds of a preterm birth subsequent to colposcopy increase with increasing depth of excision when compared with women who received a small excision (<10 mm deep). Relative to small excisions, both first births post excision and subsequent births post excision have odds ratios close to 2.0 for deep excisions (15–19 mm). Larger odds ratios were observed for very deep (≥20 mm) excisions among first birth post excision (OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.35–3.92) and among second and subsequent births post excision (OR 3.92, 95% CI taking into account clustering 1.66–9.25). In contrast, the risk of preterm birth did not increase with deeper excisions among births before colposcopy (trend OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.83–1.16, P = 0.855), but it is significant among first births post treatment (trend OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12–1.36, P < 0.001) and among second and subsequent births post treatment (trend OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.15–1.56, P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Odds ratio of preterm birth by timing of colposcopy in relation to birth and depth of excisional procedure

| Procedure at colposcopy | Timing of colposcopy in relation to the birth | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth before colposcopy | First births after colposcopy | Second or more births after colposcopy | |||||||

| Term | Preterm | OR (95% CI) | Term | Preterm | OR (95% CI) | Term | Preterm | OR (95% CI) | |

| Punch biopsy Treatment | 110 | 52 | 0.92 (0.57–1.48) | 298 | 166 | 0.90 (0.67–1.22) | 151 | 58 | 1.02 (0.63–1.66) |

| Small excision (1–9 mm deep) | 115 | 59 | Reference | 246 | 145 | Reference | 129 | 43 | Reference |

| Medium excision (10–14 mm deep) | 80 | 49 | 1.17 (0.71–1.90) | 214 | 138 | 1.08 (0.80–1.45) | 128 | 75 | 1.73 (1.09–2.74) |

| Large excision (15–19 mm deep) | 32 | 21 | 1.14 (0.58–2.21) | 56 | 64 | 1.95 (1.28–2.97) | 33 | 23 | 2.01 (1.04–3.88) |

| Very large excision (20+mm deep) | 26 | 7 | 0.50 (0.19–1.30) | 31 | 41 | 2.30 (1.35–3.92) | 13 | 16 | 3.92 (1.66–9.25) |

| Unknown treatment depth | 15 | 8 | 1.17 (0.46–3.00) | 62 | 42 | 1.13 (0.72–1.78) | 38 | 14 | 1.20 (0.58–2.47) |

| Test for trend a | OR 0.98 (0.83–1.16), P = 0.855 | OR 1.23 (1.12–1.36), P < 0.001 | OR 1.34 (1.15–1.56), P < 0.001 | ||||||

Linear trend with increasing depth category from small (1) to very large (4).

Absolute risks of preterm birth by timing of colposcopy in relation to birth are presented in Table S3. Among those with births before colposcopy the risk was similar to the risk in those who subsequently received a deep excision (6.5%) and those with a diagnostic punch biopsy (6.9%). However, among the first births following colposcopy the risk increased from 8.5% among those with a diagnostic punch biopsy to 18.9% among those with deep excisions. Although the risk among those with punch biopsy was less (6.9%) for second and subsequent births following colposcopy the absolute risk increased to 17.2% following excisional treatment (Table S3).

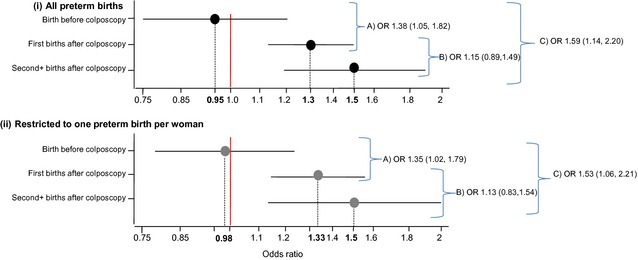

Figure 2 shows the odds ratio of preterm birth by increasing depth of excision stratified by timing of colposcopy relative to the birth and the odds ratio for the three interaction terms between the depth of excision and the timing of the colposcopy in relation to the birth. The interaction was significant both for first births post colposcopy (interaction OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.05–1.82) and for second and subsequent births post‐colposcopy (interaction OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.14–2.20) when compared with births before colposcopy. However when comparing second and subsequent births post colposcopy with first births post colposcopy, the interaction was not significant (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.89–1.49).

Figure 2.

Odds ratio of (i) all preterm births and (ii) restricted to one preterm birth per woman with increasing depth of excision (trend) stratified by timing of colposcopy relative to the birth. Interaction between depth of treatment and timing of colposcopy in relation to the birth for (A) first births post colposcopy versus births before colposcopy; (B) second+ birth post colposcopy versus first births post colposcopy and (C) second+ births post colposcopy versus births before colposcopy.

Results restricted to the first preterm birth for each woman showed a similar trend with increasing depth by timing of colposcopy relative to the birth (Figure 2); suggesting that second and subsequent births following colposcopy remain at risk of being preterm even when preceded by a term birth.

Trends with increasing depth of excision stratified by timing of colposcopy relative to the birth for each of the sensitivity analyses are presented in Figure S1. None of the results differ significantly from the main analysis, however the levels of significance of the interactions vary by subanalysis (Figure S1). In particular the analysis restricted to preterm births following spontaneous onset of labour did not differ from the analysis of all preterm births.

Discussion

Main findings

Results show an increased risk of preterm birth with increasing depth of excision for the first birth following excisional treatment. The risk with increasing depth is not limited to the first birth after treatment for cervical disease; it remains for second and subsequent births. This result was robust to a number of sensitivity analyses. In particular, adjusting for previous preterm births, which is known to be the main risk factor for preterm birth, did not change the results.

Results presented here suggest that once a woman has a deep treatment she remains at higher risk of a preterm birth throughout her reproductive life. Furthermore, even women whose first birth after treatment was at term remain at higher risk of preterm birth in their subsequent pregnancies. There is no suggestion that the absolute risk of preterm birth increases with each birth following colposcopy; rather, the absolute risks remain similar (18.9% and 17.2% for deep excisions following first and second or more births after colposcopy, respectively).

Strength and limitations

The strength of this study lies in the large number of preterm births available for analysis and the detailed data on the timing of colposcopy, the depth and the procedure received at this colposcopy. We have no information on potentially confounding factors such as smoking and ethnicity. The literature suggests that the relative risks of potential confounders (particularly smoking) are modest (around 2) and the population‐attributable fraction is small.13 The observed relationship with increasing depth is unlikely to be confounded by factors that we have no information on because no such relationship is observed among births that occur before treatment of the cervical transformation zone. Nevertheless, we cannot be certain that the observed association is causal even though it is supported both by temporality and biological gradient.14 However, even if the association is not causal, our results are of prognostic value to obstetricians; it is of clinical importance to know that women who have had excisional treatment are at high risk for preterm births throughout their reproductive life.

The robustness of the estimates to several sensitivity analyses suggest that the results were not biased by our inclusion and exclusion criteria. It is unlikely that clustering due to dependence among births of the same women was an issue in this study because our analysis took into account any potential clustering and because a similar publication7 found the cluster effect to be negligible. Further, analyses restricted to one birth per woman did not markedly impact on the results. The mean follow‐up time (for obstetric data) for women with births following colposcopy was 11.2 years. Therefore it is unlikely that a substantial number of births occurred outside the follow up, nevertheless our data are more likely to include first births following colposcopy than second or subsequent births. We had very limited information on treatments other than those performed by LLETZ so we are unable to study the effect by different types of treatment.

The quality of the birth data submitted to HES has been questioned. A quarter of the births in the study were only included thanks to HES because they were from hospitals that did not participate in the study of colposcopy. However, HES data are not perfect – some (17%) of the identified births did not have a gestational age recorded. In an unpublished comparison of 358 births identified through the Whipps Cross University Hospital obstetric database and also identified through HES we found 13 discrepancies (i.e. 3%) in terms of gestational age (all other variables did not differ). Only three of these discrepancies affected whether a birth was considered term or preterm.

Interpretation (findings in light of other evidence)

A number of published papers compare all births following colposcopy with births before colposcopy;5, 7, 8, 15 they found similar results to the literature, which only compared first birth post treatment with births before treatment (i.e. increased risk of preterm birth following the treatment). Heinonen et al.16 compared all births post treatment to women without treatment and to avoid clustering of preterm births repeated the analysis using the first birth after treatment for each woman, and the results were not significantly different between groups; however, they did not report data on depth of excision. As far as we are aware there are no other publications directly comparing the first birth post treatment with second and subsequent births post treatment.

In England only a small proportion (about 10%) of women attending colposcopy will go on to have a deep excision (≥15 mm).6 However, given that the risk of preterm birth is not restricted to the first birth following treatment it follows that the burden of disease in the population is larger than previously thought. Most women who receive treatment for cervical disease do so in their mid‐20s and early 30s and the highest fertility rates in England are observed in women aged 27–34 years.17 Furthermore fertility rates at older ages have increased in recent birth cohorts,18 particularly in women aged 35–39 years. Therefore, as more women delay pregnancy there will be an increase in the number of women treated for cervical disease before completing their childbearing.

Furthermore, there is a growing amount of research suggesting that moderately preterm infants (32–36 weeks completed gestation) are at risk of cognitive and behavioural disorders despite appearing physically mature at birth.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 This is a concern because moderately preterm births account for 66% of all preterm births in the UK25 and 71% of all preterm births in the USA.26 Additionally, in the USA, cognitive and behavioural disorders have overtaken physical impairments as the main source of child disability.27

Conclusion

For a woman being treated for cervical neoplasia in her late 20s who plans to have three children over the next decade, a deep excision could increase her risk of having at least one preterm delivery from about 21% to about 39%. Although preventing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 from developing into invasive cancer is clearly a major concern, clinical guidelines need to be updated to take into account the evidence from research such as this study.

Disclosure of interests

None declared. Completed disclosure of interests form available to view online as supporting information.

Contribution to authorship

PS had full access to all of the data in the study and confirms that it is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies are disclosed. AC coordinated the study with the help of the PaCT study group. RL and PS analysed the data and prepared results. AC and PS wrote the first draft of the report. PS, AC, PB, DP,PW, HE, NS and JP participated in the design and establishment of the study. All authors edited the report and approved the final version.

Details of ethics approval

This study was approved on 23 November 2009 by the Brompton, Harefield, and NHLI research ethics committee, Charing Cross Hospital, London (study reference number: 09/h0708/65).

Funding

This manuscript presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB‐PG‐1208‐16187). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funder had no input in the design, conduct, collation, analysis or interpretation of the data or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Sensitivity analysis.

Table S1. High risk pregnancies: ICD codes and number of women with the code in the study.

Table S2. Main characteristics of the births included in the cohort and the case‐control study.

Table S3. Absolute risks of preterm birth by timing of colposcopy in relation to birth and depth of excisional procedure.

Acknowledgements

PaCT study Group: Pathology report data entry for the study was done by Anna Parberry and Tim Pyke (Barts Health NHS Trust). Members of the PaCT Study Group are responsible for the collection of data included in this study. Hollingworth A and Wuntakal R (Whipps Cross University Hospital London), Singh N and Parberry A (Barts Health NHS Trust), Palmer J (Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield), Das N, Andrew A and Russ L (Royal Cornwall Hospital), China S, Lenton H and Raghavan R (Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust), Wood N and Preston S (Royal Preston Hospital Lancashire), Hannemann M and Fuller D (Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust), Lincoln K, Wheater G and Rolland P (The James Cook University Hospital, South Tees), Ghaem‐Maghami S and Soutter P (Hammersmith Hospital, Imperial College), Hutson R (St James University Hospital, Leeds), Senguita P and Dent J (North Durham County and Darlington Trust), Lyons D (St Mary's Hospital, Imperial College). All contributors were paid for their contribution to the data collection in this study.

Castanon A, Landy R, Brocklehurst P, Evans H, Peebles D, Singh N, Walker P, Patnick J, Sasieni P. Is the increased risk of preterm birth following excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia restricted to the first birth post treatment?. BJOG 2015;122:1191–1199.

[The copyright line for this article was changed on 11 April 2015 after original online publication].

References

- 1. Bruinsma FJ, Quinn MA. The risk of preterm birth following treatment for precancerous changes in the cervix: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJOG 2011;118:1031–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Castanon A, Brocklehurst P, Evans H, Peebles D, Singh N, Walker P, et al. Risk of preterm birth after treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among women attending colposcopy in England: retrospective‐prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;345:e5174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kyrgiou M, Koliopoulos G, Martin‐Hirsch PL, Arbyn M, Prendiville W, Paraskevaidis E. Obstetric outcome after conservative treatment for intraepithelial or early invasive cervical lesions: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet 2006;367:489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sadler L, Saftlas A, Wang W, Exeter M, Whittaker J, McCowan L. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA 2004;291:2100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Noehr B, Jensen A, Frederiksen K, Tabor A, Kjaer SK. Depth of cervical cone removed by loop electrosurgical excision procedure and subsequent risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:1232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castanon A, Landy R, Brocklehurst P, Evans H, Peebles D, Singh N, et al. Risk of preterm delivery with increasing depth of excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in England: nested case–control study. BMJ 2014;349:g6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noehr B, Jensen A, Frederiksen K, Tabor A, Kjaer SK. Loop electrosurgical excision of the cervix and subsequent risk for spontaneous preterm delivery: a population‐based study of singleton deliveries during a 9‐year period. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:33 e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jakobsson M, Gissler M, Paavonen J, Tapper AM. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and the risk for preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:504–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health & Social Care Information Centre . What is HES? 2013 [www.hscic.gov.uk/hes]. Accessed 3 March 2014.

- 10. Spong CY. Defining “term” pregnancy: recommendations from the Defining “Term” Pregnancy Workgroup. JAMA 2013;309:2445–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bornstein J, Bentley J, Bosze P, Girardi F, Haefner H, Menton M, et al. 2011 colposcopic terminology of the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:166–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cuzick J. A Wilcoxon‐type test for trend. Statist Med 1985;4:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet 2008;371:75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:295–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jakobsson M, Gissler M, Sainio S, Paavonen J, Tapper AM. Preterm delivery after surgical treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109:309–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heinonen A, Gissler M, Riska A, Paavonen J, Tapper AM, Jakobsson M. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and the risk for preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1063–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Office for National Statistics . Age‐specific fertility rates (ASFRs), constituent countries of the UK, 2010. Fertility Summary, 2010 [www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/fertility-analysis/fertility-summary/2010/uk-fertility-summary.html]. Accessed 13 September 2014.

- 18. Office for National Statistics . The Changing Age Pattern of Fertility. 2012. [www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/fertility-analysis/cohort-fertility-england-and-wales/2012/cohort-fertility-2012.html#tab-The-Changing-Age-Pattern-of-Fertility]. Accessed 13 September 2014.

- 19. Chyi LJ, Lee HC, Hintz SR, Gould JB, Sutcliffe TL. School outcomes of late preterm infants: special needs and challenges for infants born at 32 to 36 weeks gestation. J Pediatrics 2008;153:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linnet KM, Wisborg K, Agerbo E, Secher NJ, Thomsen PH, Henriksen TB. Gestational age, birth weight, and the risk of hyperkinetic disorder. Arch Dis Childhood 2006;91:655–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morse SB, Zheng H, Tang Y, Roth J. Early school‐age outcomes of late preterm infants. Pediatrics 2009;123:e622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Quigley MA, Poulsen G, Boyle E, Wolke D, Field D, Alfirevic Z, et al. Early term and late preterm birth are associated with poorer school performance at age 5 years: a cohort study. Arch Disease Childhood Fetal Neonat Ed 2012;97:F167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Baar AL, Vermaas J, Knots E, de Kleine MJ, Soons P. Functioning at school age of moderately preterm children born at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestational age. Pediatrics 2009;124:251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woythaler MA, McCormick MC, Smith VC. Late preterm infants have worse 24‐month neurodevelopmental outcomes than term infants. Pediatrics 2011;127:e622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. NHS Information Centre for health and Social Care. NHS Maternity Statistics—England. 2000. –2010 [http://www.hscic.gov.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=116&q=title%3a%22nhs+maternity+statistics%22&sort=Most+recent&size=10&page=1#top]. Accessed 3 March 2014.

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Center for Health Statistics. VitalStats. 2010. [www.cdc.gov/nchs/vitalstats.htm]. Accessed 23 September 2014.

- 27. Halfon N, Houtrow A, Larson K, P N. The changing landscape of disability in childhood. Future Child 2012;22:13–42. [http://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/22_01_02.pdf]. Accessed 18 September 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Sensitivity analysis.

Table S1. High risk pregnancies: ICD codes and number of women with the code in the study.

Table S2. Main characteristics of the births included in the cohort and the case‐control study.

Table S3. Absolute risks of preterm birth by timing of colposcopy in relation to birth and depth of excisional procedure.