Abstract

Aims

To compare the once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) receptor dulaglutide with the dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitor sitagliptin after 104 weeks of treatment.

Methods

This AWARD‐5 study was a multicentre, double‐blind trial that randomized participants to dulaglutide (1.5 or 0.75 mg) or sitagliptin 100 mg for 104 weeks or placebo (reported separately) for 26 weeks. Change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration from baseline was the primary efficacy measure. A total of 1098 participants with HbA1c concentrations ≥7.0% (≥53.0 mmol/mol) and ≤9.5% (≤80.3 mmol/mol) were randomized, and 657 (59.8%) completed the study. We report results for dulaglutide and sitagliptin at the final endpoint.

Results

Changes in HbA1c at 104 weeks were (least squares mean ± standard error) −0.99 ± 0.06% (−10.82 ± 0.66 mmol/mol), −0.71 ± 0.07% (−7.76 ± 0.77 mmol/mol) and −0.32 ± 0.06% (−3.50 ± 0.66 mmol/mol) for dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg and sitagliptin, respectively (p < 0.001, both dulaglutide doses vs sitagliptin). Weight loss was greater with dulaglutide 1.5 mg (p < 0.001) and similar with 0.75 mg versus sitagliptin (2.88 ± 0.25, 2.39 ± 0.26 and 1.75 ± 0.25 kg, respectively). Gastrointestinal adverse events were more common with dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg versus sitagliptin (nausea 17 and 15% vs 7%, diarrhoea 16 and 12% vs 6%, vomiting 14 and 8% vs 4% respectively). Pancreatic, thyroid, cardiovascular and hypersensitivity safety were similar across groups.

Conclusions

Dulaglutide doses provided superior glycaemic control and dulaglutide 1.5 mg resulted in greater weight reduction versus sitagliptin at 104 weeks, with acceptable safety.

Keywords: diabetes, dulaglutide, sitagliptin

Introduction

Dulaglutide is a long‐acting human glucagon‐like peptide 1 (GLP‐1) receptor agonist approved as a once‐weekly subcutaneous injection for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The molecule consists of two identical, disulphide‐linked chains, each containing an N‐terminal GLP‐1 (7‐37) analogue sequence that includes alanine to glycine substitution at position 8, glycine to glutamic acid at position 22, and arginine to glycine at position 36 1. The GLP‐1 analogue sequence is covalently linked to a modified human immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) heavy chain by a small peptide linker 2. Structural modifications were introduced to protect dulaglutide from degradation by dipeptidyl peptidase‐4, to reduce the risk of immune‐mediated reactions, and to prevent antigen‐independent immune activation triggered by the heavy chain of the human IgG immunoglobulin 1.

In phase III studies of up to 52 weeks duration, dulaglutide resulted in significant reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) concentration, with both fasting and postprandial glucose improvements, and weight loss. The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal‐related 3, 4, 5.

Safety and efficacy data for dulaglutide over a longer exposure period, beyond 52 weeks, are needed for full characterization of the risk–benefit profile. The present AWARD‐5 trial was designed to compare dulaglutide with sitagliptin up to 104 weeks, and placebo up to 26 weeks, in metformin‐treated patients with type 2 diabetes. The study also included an initial dose‐finding portion to identify optimum doses, where dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg were selected for further development 6. Previously reported results for comparisons between dulaglutide and sitagliptin after 52 weeks, the primary endpoint in AWARD‐5, and placebo after 26 weeks, showed that dulaglutide provided improved glycaemic control compared with sitagliptin and placebo, and confirmed safety observations from the already reported AWARD trials 3, 4, 5, 7. In the present paper, we report the long‐term data comparing dulaglutide with sitagliptin at 104 weeks, the final endpoint of the trial.

Participants and Methods

AWARD‐5 was an adaptive, seamless, parallel arm, multicentre, randomized, double‐blind, 104‐week trial. The trial addressed several sets of objectives, including selection of dulaglutide doses for phase III trials in the initial (or dose‐finding) portion, comparison of selected doses to placebo at 26 weeks, and comparison of selected doses with sitagliptin at 52 weeks (the primary endpoint of the trial) and at 104 weeks (final endpoint; Figure 1). The study was conducted at 111 sites in 12 countries. The protocol was approved by local institutional review boards, all participants provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines 8.

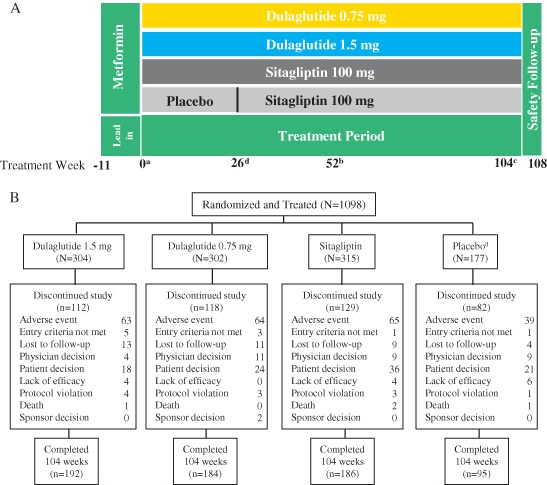

Figure 1.

Study design and participant disposition during the AWARD‐5 trial. (A) Study design and (B) participant disposition. aRandomization. bPrimary endpoint. cFinal endpoint, d Placebo period lasted for 26 weeks, followed by a switch to sitagliptin to keep the arm blinded. Only participants assigned to selected dulaglutide doses (1.5 and 0.75 mg) and comparators continued forward in the study and are represented in this figure. Adverse events included cases of severe or worsening hyperglycaemia based on prespecified criteria provided in Table S2 ‘Physicians decision’ and ‘lack of efficacy’ may have included cases of inadequate glucose control that did not meet these prespecified criteria.

The trial design and study population details have been previously published 6, 7, 9, 10 (Table S1). Briefly, eligible participants were aged 18–75 years, with type 2 diabetes (≥6 months' duration) and an HbA1c value of >8.0% (>63.9 mmol/mol) and ≤9.5% (≤80.3 mmol/mol) on diet and exercise alone, or ≥7.0% (≥53.0 mmol/mol) and ≤9.5% (≤80.3 mmol/mol) on monotherapy or combination therapy (metformin plus another oral antihyperglycaemic medication), and a body mass index of 25–40 kg/m2. The lead‐in period lasted up to 11 weeks. Participants were required to be treated with metformin monotherapy (minimum dose ≥1500 mg/day) for ≥6 weeks before randomization, which was continued during the treatment period. Following the lead‐in period, participants were assigned to treatment by one of two sequential randomization schemes (computer‐generated random sequence using an interactive voice response system): adaptive randomization during the dose‐finding portion, followed by block randomization after dose selection 9, 11, 12. After selection of dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg doses, participants from non‐selected arms were discontinued 10. Additional participants were then assigned to the remaining arms for assessment of prespecified efficacy and safety objectives: dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg, sitagliptin 100 mg, or placebo (replaced with sitagliptin after 26 weeks to maintain blinding) in a 2 : 2 : 2 : 1 ratio 6. Dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg were supplied as single‐use vials and syringes for subcutaneous administration. A sample size of 263 was chosen per arm (131 for placebo) based on a predictive power calculation at a dose selection of at least 85% to show superiority relative to sitagliptin at 52 weeks 7. During the treatment period, participants who developed persistent or worsening hyperglycaemia based on prespecified thresholds (Table S2) were discontinued, and this was recorded as an adverse event of hyperglycaemia. Limited sponsor staff were unblinded at 52 weeks to assess the primary objective. Participants and physicians were unblinded at 104 weeks. The results for the full 104‐week treatment period are reported in the present paper.

Efficacy measures included: HbA1c; percentage of participants achieving an HbA1c target of <7.0% (<53.0 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (≤47.5 mmol/mol); body weight; fasting plasma glucose (central laboratory) and fasting insulin; updated homeostastic model assessment of β‐cell function (HOMA2‐%β) and insulin sensitivity (HOMA2‐%S) 13; and lipids.

General safety assessments included: adverse events; vital signs; ECG results; laboratory variables; and hypoglycaemic episodes. Laboratory evaluations were performed at a central laboratory (Quintiles Laboratories). Hypoglycaemia was defined as plasma glucose ≤3.9 mmol/l and/or symptoms and/or signs attributable to hypoglycaemia 14. Data for hypoglycaemia were also assessed using the plasma glucose threshold <3.0 mmol/l. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer therapy, as determined by the investigator 14.

Several special safety topics were prespecified: pancreatic, thyroid, cardiovascular safety and immunogenicity. For these topics, a structured assessment plan was implemented during the trial. Pancreatic safety assessment included adjudication of pancreatic events of interest performed by an independent Clinical Endpoint Committee (Duke Clinical Research Institute) and repeated measurements of pancreatic enzymes with a further evaluation of elevations ≥3× upper limit of normal (ULN) to assess for occurrence of pancreatitis (Figure S1). The following pancreatic events were adjudicated: investigator‐reported pancreatitis, adverse events of serious or severe abdominal pain without known cause, and confirmed pancreatic enzyme elevations (≥3× ULN). The study was initiated in 2008 and pancreatic adjudication started only in 2010 (after initial post‐marketing reports of acute pancreatitis in participants treated with GLP‐1 receptor agonists). Two events occurred before the assessment process was initiated that would have required adjudication (dulaglutide 1.5 mg: 1 participant; dulaglutide 0.75 mg: 1 participant).

To determine the effect of treatment on thyroid C‐cells, blood samples were collected at baseline and every 12 weeks after baseline for calcitonin measurements. These measurements were initiated in 2009, after reports on the potential effect of GLP‐1 receptor agonists in animal studies 15. Participants who developed a calcitonin value >100 pg/ml were required to discontinue the study.

Evaluation of cardiovascular safety included cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure and lipids), vital signs and ECGs. The following cardiovascular events were adjudicated by an independent Duke Clinical Research Institute committee: all deaths and non‐fatal adverse events of myocardial infarction; hospitalization for unstable angina; hospitalization for heart failure; coronary revascularization procedures; and cerebrovascular events.

Dulaglutide antidrug antibodies were measured at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after baseline in all treatment groups. Participants with treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies underwent additional testing for (i) neutralizing dulaglutide antidrug antibodies; and (ii) cross‐reactivity to native GLP‐1 and, if positive, for the ability to neutralize native GLP‐1. Immunogenicity testing was performed by BioAgilytix (Durham, NC, USA) and Millipore (St. Charles, MO, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were based on the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) population, defined as all randomized participants. For the primary analysis, changes from baseline in HbA1c concentration and weight at 104 weeks were analysed using analysis of covariance (ancova) with factors for treatment, country and baseline value as covariates. Missing values were imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. Sensitivity analyses were conducted regarding the population and the analysis methods for change from baseline in HbA1c including ITT population analyses using a mixed‐effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) and, separately, ancova using baseline observation carried forward to impute missing data, as well as per protocol population analyses using MMRM and, separately, ancova with LOCF to impute missing data. Additionally, a delta stress test 16 was conducted to assess the robustness of the final results. The per protocol population was defined as all participants who had no major protocol violations that would undermine the interpretation of the study results. The percentage of participants in the ITT population achieving HbA1c targets (LOCF) was analysed using a logistic regression model with factors for treatment, country and a baseline value as covariates.

All continuous measures including HbA1c and weight over time were analysed using MMRM analysis with additional factors for visit and treatment‐by‐visit interaction. Least squares (LS) means and standard error (s.e.) values are reported. Adverse events were analysed using a chi‐squared test, unless there were too few events to meet the assumptions of the analysis, in which case a Fisher's exact test was conducted. The two‐sided significance level was 5% for treatment comparisons and 10% for interactions.

Results

The ITT population randomized to dulaglutide 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg doses, sitagliptin and placebo comprised 1098 participants (Figure 1B). Of these, 921 participants were randomized to dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg and sitagliptin. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were previously presented and were balanced across the groups (Table S1) 7. Briefly, the participants' mean age was 54 years, 47.4% were male, mean diabetes duration was 7 years, mean body mass index was 31 kg/m2, and mean HbA1c was 8.1% (65.0 mmol/mol). The proportions of participants in these three arms who completed the 104‐week planned treatment period were 63, 61 and 59%, respectively. Reasons for early study withdrawal were similar between groups, with adverse events (21% incidence, all groups) and participant decision (6–11% incidence) being the most common (Figure 1B). The mean duration of exposure for the dulaglutide 1.5 mg group, the dulaglutide 0.75 mg group and the sitagliptin group was 81, 82 and 79 weeks, respectively.

Efficacy

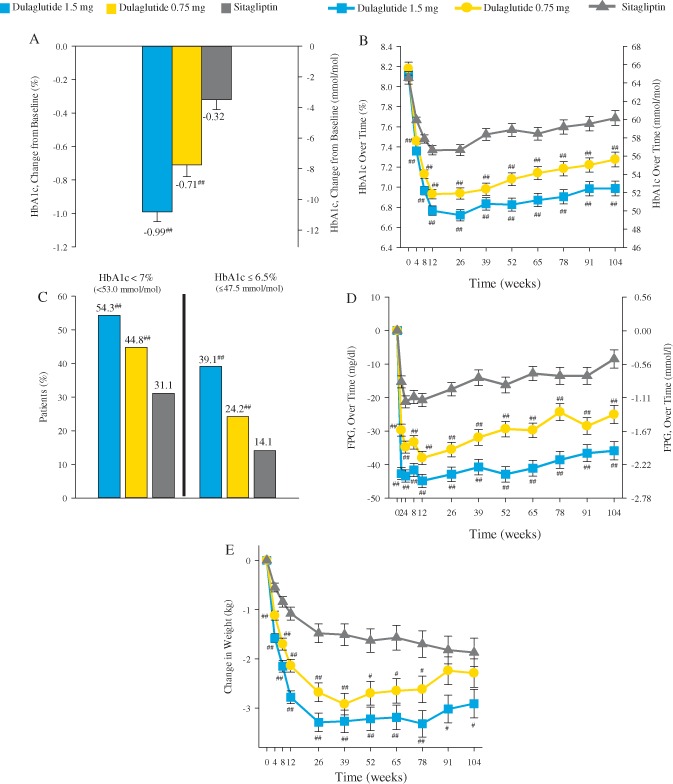

Changes from baseline to 104 weeks in HbA1c (LS mean ± s.e.) were −0.99 ± 0.06% (−10.82 ± 0.66 mmol/mol), −0.71 ± 0.07% (−7.76 ± 0.77 mmol/mol), and −0.32 ± 0.06% (−3.50 ± 0.66 mmol/mol) for dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg and sitagliptin, respectively (Figure 2A). The LS mean HbA1c changes were superior with dulaglutide 1.5 mg [LS mean difference (95% confidence interval) −0.67% (−0.84, −0.50) or −7.32 mmol/mol (−9.18, −5.47)] and dulaglutide 0.75 mg [−0.39% (−0.56, −0.22) or −4.26 mmol/mol (−6.12, −2.40)] versus sitagliptin (p < 0.001, both). Sensitivity analyses showed similar results (data not shown). In the delta stress test in the ITT population, analysed with MMRM, an HbA1c delta of 1.8% was required to be added to the imputed data in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg arm (no delta was added to the sitagliptin arm) for the difference between the dulagutide 1.5 mg arm and the sitagliptin arm to become non‐significant. The mean HbA1c assessment over time showed that dulaglutide and sitagliptin achieved the maximum effect after 3 months. The significant reduction in HbA1c and differences between groups were maintained over time up to 104 weeks for both dulaglutide doses compared with sitagliptin (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Efficacy measures through 104 weeks. (A) Change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) from baseline at 104 weeks, analysis of covariance LOCF. (B) HbA1c over time, mixed‐effects model for repeated measures (MMRM). (C) Percentage of participants achieving (HbA1c) targets at 104 weeks, logistic regression LOCF. (D) Change in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) over time, MMRM. (E) Change in weight over time, MMRM. Data presented are least squares (LS) means ± standard error (s.e.), with the exception of panel (C). #p < 0.05 versus sitagliptin; ##p < 0.001 vs sitagliptin.

At 104 weeks, the percentage of participants attaining the HbA1c target goal of <7.0% (<53.0 mmol/mol) was significantly higher in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg arms (54 and 45%, respectively) compared with sitagliptin (31%; p < 0.001, both comparisons; Figure 2C). Additionally, 39 and 24% of participants in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg arms, respectively, achieved HbA1c targets of ≤6.5% (≤47.5 mmol/mol), compared with 14% in the sitagliptin arm (p < 0.001, both comparisons).

The decrease from baseline in mean fasting plasma glucose concentration was significantly greater in both dulaglutide arms throughout the 104‐week treatment period and at final endpoint (104 week LS mean ± s.e.: −2.0 ± 0.2, −1.4 ± 0.2, and −0.5 ± 0.2 mmol/l, respectively; p < 0.001) (Figure 2D). At 104 weeks, mean changes from baseline in weight were [LS mean ± s.e. (ancova with LOCF)] −2.88 ± 0.25 kg for dulaglutide 1.5 mg, −2.39 ± 0.26 kg for dulaglutide 0.75 mg, and −1.75 ± 0.25 kg for sitagliptin. The LS mean difference between dulaglutide 1.5 mg and sitagliptin in weight loss (−1.14 kg) was significant (p < 0.001). The measurement of insulin sensitivity (HOMA2‐%S) was not different between treatment groups, while β‐cell function, as assessed by HOMA2‐%β, increased significantly more with dulaglutide 1.5 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg than with sitagliptin (Table S3).

Safety

The incidence of deaths, serious adverse events, and the most common adverse events over the 104‐week treatment period are summarized in Table 1. Three participants [dulaglutide 1.5 mg, n = 1 (stroke); sitagliptin: n = 2 (sudden cardiovascular death, uterine cancer)] died during this trial. The incidence of serious adverse events reported by participants was similar across treatments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Safety assessments, change from baseline in vital signs and treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies in the period up to 104 weeks

| Variable | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg (N = 304) | Dulaglutide 0.75 mg (N = 302) | Sitagliptin (N = 315) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death, n (%) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Serious adverse events, n (%) | 36 (12) | 23 (8) | 32 (10) |

| Infections and infestation | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Cardiac disorders | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Neoplasms | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Gastrointestinal events | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Renal/urinary disorders | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Treatment‐emergent adverse events ≥1, n (%) | 259 (85)* | 255 (84)* | 242 (77) |

| Treatment‐emergent adverse events in ≥5% participants, n (%) | |||

| System organ class gastrointestinal events | 138 (45)* | 122 (40)* | 94 (30) |

| Nausea | 53 (17)* | 44 (15)* | 21 (7) |

| Diarrhoea | 49 (16)* | 36 (12)* | 18 (6) |

| Vomiting | 41 (14)* | 25 (8)* | 11 (4) |

| Abdominal pain | 21 (7) | 13 (4) | 11 (4) |

| Dyspepsia | 18 (6) | 19 (6) | 14 (4) |

| Abdominal distension | 13 (4) | 15 (5) | 3 (1) |

| System organ class infections and infestation | 135 (44) | 125 (41) | 130 (41) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 42 (14) | 47 (16) | 45 (14) |

| Upper respiratory infection | 22 (7) | 22 (7) | 19 (6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 20 (7) | 22 (7) | 19 (6) |

| Influenza | 16 (5) | 18 (6) | 13 (4) |

| Other adverse events | |||

| Hyperglycaemia | 30 (10) | 38 (13) | 50 (16) |

| Decreased appetite | 29 (10)* | 17 (6) | 10 (3) |

| Back pain | 20 (7) | 27 (9) | 19 (6) |

| Headaches | 29 (10) | 27 (9) | 26 (8) |

| Cough | 19 (6) | 11 (4) | 16 (5) |

| Arthralgia | 14 (5) | 19 (6) | 14 (4) |

| Dizziness | 7 (2) | 18 (6) | 14 (4) |

| Injection site reactions | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| Discontinuation resulting from adverse events, n (%) | 63 (21) | 64 (21) | 65 (21) |

| Vital signs, LS mean (s.e.) | |||

| SBP, mmHg | −0.1 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.8) | <0.1 (0.8) |

| DBP, mmHg | 0.4 (0.5) | 1.4 (0.5)* | −0.4 (0.5) |

| Pulse rate, beats/min | 2.3 (0.5)† | 2.8 (0.5)† | −0.8 (0.5) |

| ECG measurement, LS mean (s.e.) | |||

| PR interval, ms | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.9) |

| Treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies, n (%) | |||

| Dulaglutide antidrug antibodies | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Neutralizing dulaglutide | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Cross‐reactive native‐sequence GLP‐1 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Neutralizing native‐sequence GLP‐1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; LS, least squares; SBP, systolic blood pressure; s.e., standard error.

P < 0.05 vs sitagliptin. † P < 0.001 vs sitagliptin.

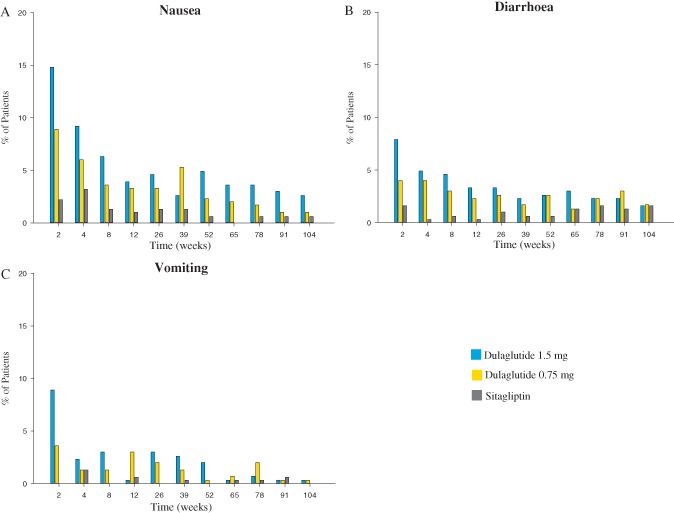

Up to 104 weeks, there was a higher incidence of adverse events among participants treated with dulaglutide compared with sitagliptin (p = 0.008, dulaglutide 1.5 mg; p = 0.017, dulaglutide 0.75 mg) because of the more common occurrence of gastrointestinal adverse events in the dulaglutide arms (Table 1). Nausea, diarrhoea and vomiting were the most commonly reported adverse events. The incidence of common gastrointestinal adverse events in dulaglutide‐treated participants was highest after 2 weeks of treatment (9–15%) and decreased at subsequent visits (1–6% between week 6 and week 52, 1–4% between week 52 and week 104; Figure 3). These gastrointestinal adverse events were mostly mild to moderate, with ≤3% of participants reporting severe episodes. The most common events causing discontinuation were hyperglycaemia [dulaglutide 1.5 mg: n = 28 (9%); dulaglutide 0.75 mg: n = 38 (13%); sitagliptin: n = 44 (14%)] and nausea [dulaglutide 1.5 mg: n = 9 (3%); dulaglutide 0.75 mg: n = 3 (1%); sitagliptin: n = 0].

Figure 3.

Percentage of participants experiencing (A) nausea, (B) diarrhoea and (C) vomiting by week.

The incidence of hypoglycaemia (≤3.9 mmol/l threshold) at 104 weeks was 12.8% for dulaglutide 1.5 mg, 8.6% for dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 8.6% for sitagliptin; the mean (standard deviation) 1‐year adjusted rates (events/participant/year) were 0.3 (1.1), 0.2 (2.0), and 0.2 (1.4), respectively; no severe episodes were reported. Hypoglycaemia data per <3.0 mmol/l threshold are provided in the Supplement (Table S3).

At 104 weeks, there were no differences in systolic blood pressure (SBP) between the dulaglutide and sitagliptin arms (Table 1). There was also no difference in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between dulaglutide 1.5 mg and sitagliptin. Dulaglutide 0.75 mg had a significantly larger mean increase in DBP compared with sitagliptin (p = 0.015). An increase of ∼2–3 beats/min in LS mean pulse rate with both dulaglutide doses, and a small decrease with sitagliptin was observed (p < 0.001, dulaglutide vs sitagliptin, both; Table 1). No significant changes in ECG findings or fasting lipids were observed (Table 1). Throughout the 104‐week study, a total of 62 participants (5.6%) reported cardiovascular adverse events with no significant difference in incidence across treatments (dulaglutide 1.5 mg: 5.6%; dulaglutide 0.75 mg: 6.0%; sitagliptin: 4.4%). A total of 15 participants had cardiovascular events confirmed by adjudication: dulaglutide 1.5 mg, n = 6 (2.0%); dulaglutide 0.75 mg, n = 4 (1.3%); sitagliptin, n = 5 (1.6%).

There were two events of acute pancreatitis confirmed by adjudication in participants treated with sitagliptin and none in dulaglutide‐treated participants. Increases in median values of pancreatic enzymes were observed in all groups at 104 weeks (Table S3). Compared with sitagliptin, both dulaglutide doses were associated with significantly greater median increases in serum lipase, total amylase and pancreatic amylase (p‐amylase; all within the normal range) and significantly greater incidence in treatment‐emergent high values (above the ULN) for p‐amylase; and between the dulaglutide 1.5 mg arm and sitagliptin arm for lipase. The assessment of clinically relevant categories ≥3× ULN did not indicate significant differences in incidence of this abnormality between groups.

One participant from the dulaglutide 1.5 mg arm was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer (Stage 1). There were no between‐group differences in median change from baseline for calcitonin or number of participants with treatment‐emergent elevated calcitonin levels [dulaglutide 1.5 mg: n = 5 (2.1%); dulaglutide 0.75 mg: n = 3 (1.3%); sitagliptin: n = 4 (1.7%)].

Nine participants treated with dulaglutide (1.3%) had treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies (Table 1); dulaglutide‐neutralizing antibodies were present in 2 of the 9. Two participants developed native‐sequence GLP‐1 cross‐reactive antibodies; neither was neutralizing. None of the participants with treatment‐emergent dulaglutide antidrug antibodies reported systemic hypersensitivity events or injection site reactions. Five other participants who received dulaglutide 0.75 mg, and 3 participants who received sitagliptin, reported systemic hypersensitivity events during the trial.

Discussion

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic disease that requires lifelong management, including administration of glucose‐lowering agents to maintain glycaemic control and prevent development of chronic complications. For this reason, long‐term data (>52 weeks) from randomized, controlled trials are important for the risk–benefit assessment of these medications. In AWARD‐5, both doses of the once‐weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist dulaglutide consistently led to superior HbA1c reductions compared with sitagliptin at 104 weeks. Participants in the dulaglutide 1.5 mg arm also experienced significantly greater weight loss than the sitagliptin group. Over 104 weeks, safety evaluations did not reveal any increased risks of cardiovascular, pancreatic or thyroid adverse events. Dulaglutide exposure was associated with a low incidence of participants developing dulaglutide‐specific antidrug antibodies and no signs of increased risk of immune‐mediated hypersensitivity events were noted. The most common adverse events associated with dulaglutide were gastrointestinal‐related, consistent with the GLP‐1 receptor agonist class.

As previously reported, both dulaglutide 1.5 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg were superior to sitagliptin after 52 weeks 7. The results presented here show persistent differences between dulaglutide and sitagliptin, up to 104 weeks, with respect to glucose control [change in HbA1c, percentage of participants reaching prespecified targets <7.0% (<53.0 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (≤47.5 mmol/mol) and change in fasting plasma glucose]. In addition, treatment with the 1.5 mg dulaglutide dose was associated with a stable decrease in body weight (∼3.0 kg), and was significantly greater than the decrease observed with sitagliptin. It is important to note that a mild upward shift in HbA1c in all three groups was observed after 52 weeks of therapy in the ITT population (Figure 2B), but not when the participants' data were averaged at every visit for the entire 104 week period (ITT population; data not shown). The statistical method to adjust for missing data takes into account within‐subject correlations in HbA1c, even for participants who might have dropped out early because of disease progression or deteriorating compliance with other therapeutic measures which would be reflected in increasing HbA1c. This discrepancy between the LS means and the raw means may be attributable to the progression of disease or deteriorating compliance which would not be taken into account with raw means. In addition, the effects of randomized therapies on body weight in AWARD‐5 may have been confounded by the design of the lead‐in period, which required participants to be treated with ≥1500 mg of metformin and discontinue any other glucose‐lowering agents used before the study. This may explain the continuously decreasing body weight with sitagliptin (effect of metformin), an observation not seen in other studies in which this medication was investigated (Figure 2E). This could have contributed to the smaller than expected difference between the dulaglutide 0.75 mg dose and sitagliptin at the final endpoint because of potentially less than additive weight‐lowering effects of dulaglutide and metformin on body weight. Despite the robust effect on glycaemic control, the incidence of hypoglycaemia was low with dulaglutide, and similar to the risk with sitagliptin. Hypoglycaemia risk was similar to that reported with other GLP‐1 receptor agonists when used in combination with metformin and when comparable glycaemic thresholds for hypoglycaemia definitions are used (3.0–3.1 mmol/l) 17, 18. The low incidence of hypoglycaemia in dulaglutide‐treated participants is considered to be related to its mechanism of action, a glucose‐dependent enhancement of insulin secretion that avoids β‐cell overstimulation and hyperinsulinaemia 1, 2, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22.

Dulaglutide was associated with an increased incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events similar to other GLP‐1 receptor agonist medications 18, 21, 22, 23, 24. These adverse events were reported mostly during the initial 2 weeks of treatment, with a steady decrease in reporting in subsequent weeks. The events were mostly mild to moderate and rarely caused treatment withdrawal (1–3% of participants).

Reported cardiovascular adverse events and adjudicated cardiovascular events did not suggest an increased cardiovascular risk with dulaglutide. The most notable cardiovascular observation with dulaglutide treatment was a slight increase in pulse rate, the clinical relevance of which is unknown. This observation is consistent with other GLP‐1 receptor agonist medications 21, 25.

AWARD‐5 provides a systematic assessment of pancreatic safety in dulaglutide‐treated participants over a 2‐year period. There were no events of acute pancreatitis in dulaglutide groups. Pancreatic enzyme elevations were observed with dulaglutide treatment and also with sitagliptin treatment (in comparison with placebo) 7; changes were greater with dulaglutide. The observed increases caused more frequent reporting of values above the ULN with dulaglutide, but there was no difference in reporting of more clinically relevant increases ≥3× ULN. The assessment of participants with confirmed enzyme elevations ≥3× ULN did not result in any additional clinically relevant findings. These clinical observations are consistent with recently reported data from a 52‐week study of cynomolgus monkeys at 500 times the dulaglutide exposure level in humans that did not reveal any relevant structural changes in the pancreas 26.

Overall, no findings were reported to indicate thyroid C‐cell‐related safety concerns with dulaglutide treatment. Lack of effect on the thyroid in humans with dulaglutide is consistent with the lack of effect observed with other GLP‐1 receptor agonists and probably reflects differences between rodent models and humans 27, 28, 29, 30, 31.

The incidence of dulaglutide antidrug antibodies was low in exposed participants, and there were no indications that an immune response against dulaglutide causes systemic hypersensitivity events or injection site reactions.

The main limitation of the present study was the discontinuation rate for participants treated with either dulaglutide or sitagliptin of ∼40%. The discontinuation rate in AWARD‐5 can be explained by the long duration of the study (2 years), as it was similar to discontinuation rates reported in other long‐term trials of similar duration that investigated other glucose‐lowering agents 32, 33, 34. For example, in the LEAD‐3 trial, which compared the once‐daily GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide and glimepiride, the proportion of liraglutide‐treated participants who discontinued treatment before the completion of the planned 2‐year follow‐up period was ∼60% 35. In spite of missing data, the consistent results of the sensitivity analysis for missing data showed that this issue did not affect the outcome of the analyses of effect of randomized treatments on HbA1c. Even under the most conservative assumptions about missing data the conclusions were the same.

In conclusion, dulaglutide 1.5 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg were found to provide persistently superior glycaemic control compared with sitagliptin over 104 weeks. The long‐term safety profile of dulaglutide is consistent with other GLP‐1 receptor agonists and includes increased incidence of mostly mild to moderate gastrointestinal events, which abate with continued treatment and result in low rates of discontinuation and small increases in pulse rate. Overall, these results support an acceptable risk–benefit profile for once‐weekly dulaglutide.

Conflict of Interest

R. S. W. has participated in multicentred clinical trials sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company, Medtronic Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Biodel, Novo Nordisk and Astra Zeneca. B. G. has received fees for consultancy, advisory boards, speaking, travel or accommodation from GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi‐Aventis, Novartis, Abbott, Lifescan, Roche Diagnostics, Medtronic and Menarini. G. U. is supported in part by research grants from the American Diabetes Association (7‐03‐CR‐35), PHS grant UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical Translational Science Award Program (M01 RR‐00039), National Institute of Health, National Center for Research Resources, and from unrestricted research grants from pharmaceutical companies (Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Merck) to Emory University, and has received fees for consultancy and advisory boards from Sanofi, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim. M. N. has received research grants from Berlin‐Chemie AG/Menarini, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis Pharma AG, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, MetaCure Inc., Roche Pharma AG, Novo Nordisk Pharma GmbH and Tolerx Inc. for participation in multicentric clinical trials. M. N. has received consulting fees or/and honoraria for membership in advisory boards or/and honoraria for speaking from Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc., AstraZeneca, Mjölndal, Berlin Chemie AG/Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb EMEA, Diartis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, F. Hoffmann‐LaRoche Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline LLC, Intarcia Therapeutics, Inc., MannKind Corp., Merck Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Merck Sharp Dohme Corp., Novartis Pharma AG, NovoNordisk A/S, Novo Nordisk Pharma GmbH, Sanofi‐Aventis Pharma, Takeda, Versartis and Wyeth Research; including reimbursement for travel expenses in connection with the above‐mentioned activities. O. V., R. T. H., Z. S. and Z.M. are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. No other conflicts of interest were reported.

Author contributions were as follows: R. S. W., B. G., G. U., M. A. N., Z. S. and Z. M. participated in the acquisition and interpretation of the data, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Z. S. provided statistical analyses of the data. Z. S. and Z. M. performed a supervisory role of the manuscript. All authors participated sufficiently to take public responsibility of the manuscript and approved of the final version for submission.

Supporting information

Table S1. Baseline characteristics and demographics of randomized participants.

Table S2. Criteria for discontinuation, thresholds for fasting plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin.

Table S3. Other safety outcomes of interest, change from baseline at 104 weeks or incidence.

Figure S1. Pancreatic enzymes: safety monitoring algorithm in patients without symptoms of pancreatitis.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the AWARD‐5 team and their staff for the conduct of this study, the volunteers for their participation, and Oralee J. Varnado, PhD, Whitney J. Sealls, PhD and Ryan T. Hietpas, PhD, Eli Lilly and Company, for writing assistance. This work was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Additional details of this study, entitled ‘A Study of LY2189265 Compared to Sitagliptin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Metformin’, can be found at Clinical Trial Registry: http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00734474).

References

- 1. Glaesner W, Vick AM, Millican R et al. Engineering and characterization of the long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue LY2189265, an Fc fusion protein. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010; 26: 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barrington P, Chien JY, Tibaldi F, Showalter HD, Schneck K, Ellis B. LY2189265, a long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue, showed a dose‐dependent effect on insulin secretion in healthy subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wysham C, Blevins T, Arakaki R et al. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide added on to pioglitazone and metformin versus exenatide in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐1). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2159–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umpierrez G, Povedano S, Manghi F, Shurzinske L, Pechtner V. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide monotherapy vs metformin in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐3). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2168–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T et al. Once‐weekly dulaglutide versus once‐daily liraglutide in metformin‐treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐6): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Skrivanek Z, Gaydos B, Chien J et al. Dose‐finding results in an adaptive, seamless, randomised trial of once weekly dulaglutide combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐5). Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 748–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nauck M, Weinstock RS, Umpierrez GE, Guerci B, Skrivanek Z, Milicevic Z. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide versus sitagliptin after 52 weeks in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD‐5). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2149–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Medical Association declaration of Helsinki . Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997; 277: 925–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Geiger MJ, Skrivanek Z, Gaydos B, Chien J, Berry S, Berry D. An adaptive, dose‐finding, seamless phase 2/3 study of a long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog (dulaglutide): trial design and baseline characteristics. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6: 1319–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skrivanek Z, Chien J, Gaydos B, Heathman M, Geiger M, Milicevic Z. Dose finding results in an adaptive trial of dulaglutide combined with metformin in type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐5). Diabetologia 2013; 56: S402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Skrivanek Z, Berry S, Berry D et al. Application of adaptive design methodology in development of a long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog (dulaglutide): statistical design and simulations. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6: 1305–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Spencer K, Colvin K, Braunecker B et al. Operational challenges and solutions with implementation of an adaptive seamless phase 2/3 study. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2012; 6: 1296–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1487–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia . Defining and reporting hypoglycemia in diabetes: a report from the American Diabetes Association Workgroup on Hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 1245–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Food and Drug Administration . Novo Nordisk's Liraglutide (injection) for the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes, NDA 22‐341, briefing document: Endocrine and Metabolic Drug Advisory Committee 2 April 2009. 2009. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/EndocrinologicandMetabolicDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM148659.pdf. Accessed 12 January 2015.

- 16. Carpenter J, Kenward M. Chapter 6.5: pattern mixture approach with longitudinal data via MI Missing Data in Randomised Controlled Trials – a Practical Guide. London: Medical Statistics Unit, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2007. Available from URL: http://www.missingdata.org.uk. Accessed 1 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahren B, Leguizamo Dimas A, Miossec P, Saubadu S, Aronson R. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once‐daily morning or evening injections in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin (GetGoal‐M). Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2543–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bergenstal RM, Wysham C, Macconell L et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐2): a randomised trial. Lancet 2010; 376: 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schwartz SS. A practice‐based approach to the 2012 position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the study of diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin 2013; 29: 793–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bolli GB, Munteanu M, Dotsenko S et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily vs. placebo in people with Type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on metformin (GetGoal‐F1). Diabet Med 2014; 31: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pratley RE, Nauck M, Bailey T et al. Liraglutide versus sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who did not have adequate glycaemic control with metformin: a 26‐week, randomised, parallel‐group, open‐label trial. Lancet 2010; 375: 1447–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)‐2 study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. (2013) Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐6): a randomised, open‐label study. Lancet 2013; 381: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week randomised, parallel‐group, multinational, open‐label trial (LEAD‐6). Lancet 2009; 374: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Robinson LE, Holt TA, Rees K, Randeva HS, O'Hare JP. Effects of exenatide and liraglutide on heart rate, blood pressure and body weight: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e001986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vahle J, Byrd R, Sorden S et al. Evaluation of serum amylase and lipase, and expanded pancreatic histology in monkeys following chronic administration of dulaglutide, a long acting GLP‐1 receptor agonist (abstract). NIDDK 2013 Meeting, Pancreatitis‐Diabetes‐Pancreatic Cancer Workshop. Bethesda, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Waser B, Beetschen K, Pellegata NS, Reubi JC. Incretin receptors in non‐neoplastic and neoplastic thyroid C cells in rodents and humans: relevance for incretin‐based diabetes therapy. Neuroendocrinology 2011; 94: 291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hegedus L, Moses AC, Zdravkovic M, Le Thi T, Daniels GH. GLP‐1 and calcitonin concentration in humans: lack of evidence of calcitonin release from sequential screening in over 5000 subjects with type 2 diabetes or nondiabetic obese subjects treated with the human GLP‐1 analog, liraglutide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bjerre Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S et al. Glucagon‐like Peptide‐1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C‐cells causing calcitonin release and C‐cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 1473–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vahle J, Sorden S, Rosol T et al.. Thyroid C‐cell morphology, morphometry, and serum calcitonin in male monkeys following twice weekly subcutaneous injection of dulaglutide for 52 weeks (abstract). American College of Toxicology 2013 Meeting. 2013, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 31. Byrd R, Sorden S, Ryan T et al.. Effects of dulaglutide on calcium chloride stimulated plasma calcitonin and thyroid c‐cell mass, hyperplasia, and neoplasia in rats (abstract). American College of Toxicology 2013 Meeting. 2013, San Antonio, TX, USA.

- 32. Matthews DR, Dejager S, Ahren B et al. Vildagliptin add‐on to metformin produces similar efficacy and reduced hypoglycaemic risk compared with glimepiride, with no weight gain: results from a 2‐year study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12: 780–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosenstock J, Cefalu WT, Hollander PA et al. Two‐year pulmonary safety and efficacy of inhaled human insulin (Exubera) in adult patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 1723–1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Macconell L, Pencek R, Li Y, Maggs D, Porter L. Exenatide once weekly: sustained improvement in glycemic control and cardiometabolic measures through 3 years. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2013; 6: 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garber A, Henry RR, Ratner R et al. Liraglutide, a once‐daily human glucagon‐like peptide 1 analogue, provides sustained improvements in glycaemic control and weight for 2 years as monotherapy compared with glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Baseline characteristics and demographics of randomized participants.

Table S2. Criteria for discontinuation, thresholds for fasting plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin.

Table S3. Other safety outcomes of interest, change from baseline at 104 weeks or incidence.

Figure S1. Pancreatic enzymes: safety monitoring algorithm in patients without symptoms of pancreatitis.