Abstract

Background

Until now, almost nothing is known about the tumorigenesis of atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS). Our hypothesis is that AFX is the non-infiltrating precursor lesion of PDS.

Materials and Methods

We performed the world-wide most comprehensive immunohistochemical and mutational analysis in well-defined AFX (n=5) and PDS (n=5).

Results

In NGS-based mutation analyses of selected regions by a 17 hotspot gene panel of 102 amplicons we could detect TP53 mutations in all PDS as well as in the only analyzed AFX and PDS of the same patient. Besides, we detected mutations in the CDKN2A, HRAS, KNSTRN and PIK3CA genes.

Performing immunohistochemistry for CTNNB1, KIT, CDK4, c-MYC, CTLA-4, CCND1, EGFR, EPCAM, ERBB2, IMP3, INI-1, MKI67, MDM2, MET, p40, TP53, PD-L1 and SOX2 overexpression of TP53, CCND1 and CDK4 was seen in AFX as well as in PDS. IMP3 was upregulated in 2 AFX (weak staining) and 4 PDS (strong staining).

FISH analyses for the genes FGFR1, FGFR2 and FGFR3 revealed negative results in all tumors.

Conclusions

UV-induced TP53 mutations as well as CCND1/CDK4 changes seem to play essential roles in tumorigenesis of PDS. Furthermore, we found some more interesting mutated genes in other oncogene pathways (activating mutations of HRAS and PIK3CA). All AFX and PDS investigated immunohistochemically presented with similar oncogene expression profiles (TP53, CCND1, CDK4 overexpression) and the single case with an AFX and PDS showed complete identical TP53 and PIK3CA mutation profiles in both tumors. This reinforces our hypothesis that AFX is the non-infiltrating precursor lesion of PDS.

Keywords: atypical fibroxanthoma, CDK4, CCND1, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, TP53

INTRODUCTION

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS) are rare tumors that typically arise on sun-exposed skin in the head and neck region of elderly patients [1]. Histologically, AFX can be composed of pleomorphic, spindle or epithelioid cells arranged in a haphazard or storiform pattern. The term “pleomorphic dermal sarcoma” was introduced by Fletcher [2] and describes tumors having been referred to “cutaneous undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas” or “superficial malignant fibrous histiocytomas” in the past. These tumors present with a similar morphology to AFX, but in addition, show extensive invasion of deeper structures [1, 2]. Both, AFX and PDS are usually negative for cytokeratins, S100, CD34, and desmin [3].

The most important risk factor for AFX is, similar to cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (cSCC), UV exposure. The link of UV dependency to PDS is less clear. AFX generally do not recur after complete excision. In contrast, PDS, have the potential for local recurrence, metastasis and disease-specific death and there are no standard effective treatments beyond surgery and radiation in metastasized stages [4–6].

Until now, there is considerable controversy regarding the question if AFX and PDS are related neoplasms arising from a common mesenchymal progenitor cell, may represent “two poles of the same disease” or represent separate entities [5],

Over the last years, NGS analyses in cSCC identified common gene alterations in TP53, NOTCH1, RAS, CDKN2A, AJUBA, CASP8, FAT1, KMT2C (MLL3), PIK3CA, SOX2 and CCND1 [7, 8]. In contrary, there are just a few small studies which identified UV-signature TP53 mutations in AFX (66.7-70%) [4, 5]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies investigating other oncogenes or therapeutic structures in AFX or PDS.

For that reason, we performed, based on our hypothesis that AFX is the non-infiltrating precursor lesion of PDS, comparing immunohistochemical, NGS as well as FISH analyses of several proteins/genes in well characterized AFX and PDS samples including one case with an initially diagnosed AFX and a PDS 3 years later to get insights of their possible evolution. Furthermore, we hoped to identify diagnostic or prognostic markers as well as target structures for therapies in advanced tumor stages.

RESULTS

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The results of all immunohistochemical stainings are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. IHC Results (+ slightly positive, ++ moderately positive, +++ strongly positive, - negative, NT no tumor).

| CCND1 | CDK4 | c-MYC | CTLA-4 | CTNNB1 | EGFR | EPCAM | ERBB2 | IMP3 | KIT | INI-1 | MKI67 | MDM2 | MET | p40 | TP53 | PD-L1 | SOX2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFX | ||||||||||||||||||

| + | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4×3-5% | ||||||||||||||

| ++ | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| +++ | 3 | 1×20-25% | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| - | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | ||

| NT | ||||||||||||||||||

| PDS | 1×3-5% | |||||||||||||||||

| + | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4×10-15% | 1 | |||||||||||||

| ++ | 4 | 6 | 1×20-25% | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| +++ | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| - | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | ||

| NT | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Positive expression

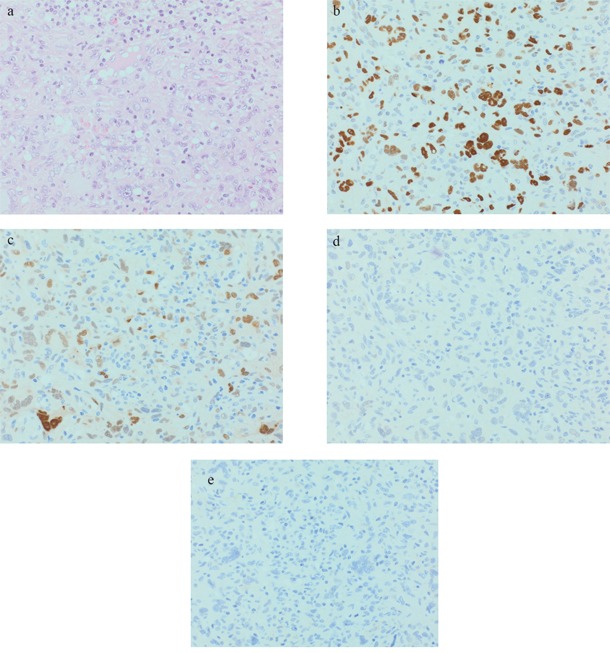

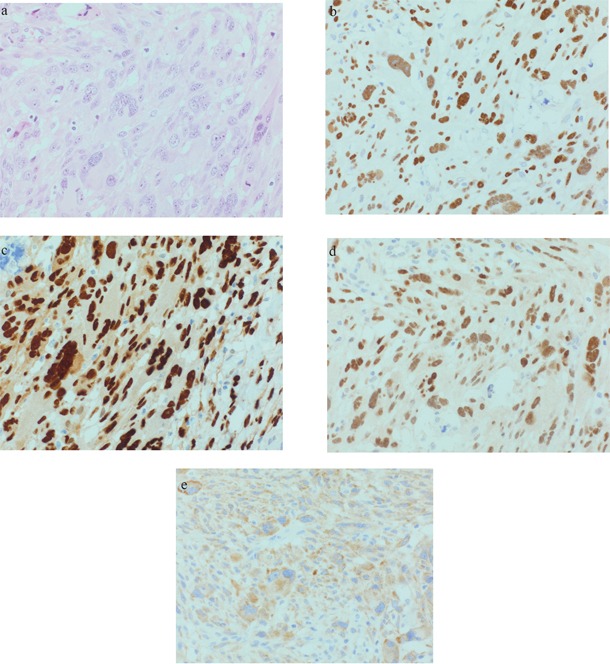

In 9 analyzed tumors, TP53 was moderately to strongly expressed in 3 AFX and 2 PDS (see Figure 1 and 2b). CCND1 was moderately to strongly expressed in 3 AFX and 4 PDS. 2 AFX and 1 PDS with CCND1 expression were also strongly positive for CDK4 (see Figure 1 and 2c and 2d). IMP3 was upregulated in 1 AFX and 3 PDS (see Figure 1 and 2e). Case 5 showed strong TP53 and CCND1 expression in both tumor samples, CDK4 was negative and IMP3 was focally positive in the AFX and diffuse positive in the PDS sample. c-MYC was slightly positive in 1 PDS. For INI-1, no loss of expression could be found.

Figure 1. Representative AFX (case 4): a. 40xHE; b. 40xp53; c. 40xCyclin D1; d. 40xCDK4; e. 40xIMP3.

Figure 2. Representative PDS (case 8): a. 40xHE; b. 40xp53; c. 40xCyclin D1; d. 40xCDK4; e. 40xIMP3.

One case showed strong positivity for p40, TP53, CCND1 and EGFR. Although a pan-cytokeratin staining had been negative at the time of initial diagnosis, an additional CK5/6 staining was positive at present. Due to this, we had to revise the archival diagnosis of an AFX and diagnosed a SCC (not shown in the tables) and excluded the case from further analyses.

Negative expression

EGFR was slightly expressed in 1 AFX and strongly expressed in 1 PDS corresponding to the usual skin expression of control samples. KIT was not expressed by any of the tumors. No expression of CTNNB1, CTLA4, EPCAM, ERBB2, MET, p40, PD-L1 and SOX2 could be detected in any of the tumors, PD-L1 was negative in tumor as well as stromal cells.

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH)

We could not detect any FGFR1 amplification in 8 of 10 tumors investigated. One AFX sample did not show any signal and one PDS sample exhibited too low tumor content to analyze 60 nuclei, our threshold for evaluating FISH analyses.

Moreover, we could not identify any FGFR2 nor FGFR3 translocation in our tumors.

Next-generation-sequencing (NGS)

The results of all Next-Generation-Sequencing analyses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Primer pairs and results of the NGS (n/a= not applicable= low DNA quality).

| Gene | Exon | Codon | Mutation status | Freq. (%) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF | 11, 15 | 439-477, 582-620 | Wild type | ||

| CDK4 | 2 | 1-57 | Wild type | ||

| CDKN2A | 1, 2 | 38-50, 136-152 |

Case 6 (PDS): EX1: c148C>T p.Q50* AND EX2: c.442G>A p.A148T |

56.32 22.24 | Truncated protein Described, function unknown [52] |

| GNA11 | 5 | 203-245 | Wild type | ||

| GNAQ | 5 | 203-245 | Wild type | ||

| HRAS | 2, 3, 4 | 1-37, 38-97, 98-146 |

Case 6 (PDS): EX2: c.37G>C p.G13R |

19.34 | Activating |

| IDH1 | 4 | 89-138 |

Case 7 (PDS): EX4: c379C>T p.P127S |

18.02 | Described, function unknown [53] |

| KIT | 9, 11, 13, 17, 18 | 450-513, 550-591, 624-659, 784-824, 825-861 | Wild type | ||

| KNSTRN | 1 | 1-38 |

Case 6 (PDS): EX1: c.71C>T p.S24F |

29.04 | Described [8] |

| KRAS | 2-4 | 1-37, 41-92, 98-150 | Wild type | ||

| NRAS | 2-4 | 1-37, 41-92, 98-150 | Wild type | ||

| OXA1L | 1 | 1-77 | Wild type | ||

| PDGFRA | 12, 14, 18 | 552-595, 632-667, 814-854 | Wild type | ||

| PIK3CA | 9, 20 | 514-555, 980-1069 |

Case 5 (AFX recurring as PDS, both tumors): EX9: c.1624G>A p.E542K |

35.99/48.07 | Activating |

|

Case 6 (PDS): EX9: c.1633G>A p.E545K |

36.43 | Activating | |||

| PTEN | 1-7 | 1-26, 27-55, 56-70, 71-84, 85-164, 165-211, 212-267, 268-342, 343-404 | Wild type | ||

| RAC1 | 2 | 13-35 | Wild type | ||

|

Case 5 (AFX and PDS, both tumors): EX6: c.672+1G>C AND EX8: c.818G>A p.R273H |

19.19/24.6 36.47/47.68 | Splice site base exchange Non-functional proteinneutral | |||

|

Case 6 (PDS): EX7: c.697C>T p.H233Y |

14.22 | neutral | |||

| TP53 | 5-9 | 126-186, 187-224, 225-261, 262-306, 307-331 |

Case 7 (PDS): EX6: c.637C>T p.R213*Case 8 (PDS) |

24.98 n/a |

Truncated protein |

|

Case 9 (PDS): EX6: c.585_586CC>>TT p.R196* AND EX7: c.712T>A p.C238S |

36.6 20.53 |

Truncated protein Non-functional protein | |||

|

Case 10 (PDS): EX5: c.490A>T p.K164* AND EX6: c.586C>T p.R196* |

22.56 9.98 |

Truncated protein Truncated protein |

Mutated genes

By sequencing exons 5-8 of TP53, mutations could be detected in all 5 analyzable PDS (case 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10). In case 8, the tumor content was too low for mutation analyses (<10%). In the two PDS (case 6 and 10) which were immunohistochemically negative for TP53, TP53 mutations could also be found (case 6 with a mutation without effect on the protein function; neutral, case 10 with a truncated protein, according to the IARC TP53 database, http://p53.iarc.fr/TP53GeneVariations.aspx).

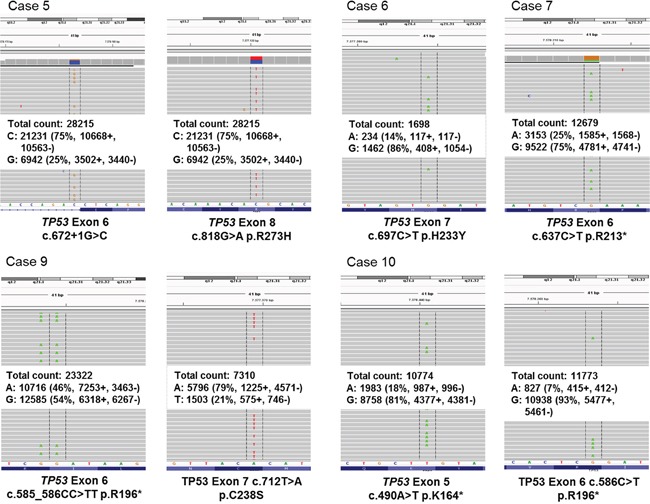

Two of the 4 PDS (case 9 and 10) as well as the case with an AFX and PDS (case 5) had double-hit mutations in the TP53 gene. Four TP53 mutations took place at dipyrimidine sites being C to T transitions, case 9 carried a CC>TT tandem base substitution (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. TP53 mutational analyses.

TP53 exons 5-8 were analyzed by Next Generation Sequencing. Integrative genomic viewer visualization of all detected TP53 mutations in AFX and PDS. In case 8, the tumor content was too low for mutation analyses (<10%).

Besides the TP53 mutations, case 5 presented with an activating PIK3CA mutation and complete identical TP53 and PIK3CA mutation pattern in both tumors. Case 6 had two mutations in the CDKN2A, one mutation in the HRAS, one in the KNSTRN and one activating mutation in the PIK3CA gene. Case 7 presented an IDH1 mutation.

Wild-type-genes

All other investigated genes (compare Table 2) did not show any mutation.

DISCUSSION

TP53 mutations seem to be essential in the development of PDS (driver mutation). Our mutation analyses using NGS could detect TP53 mutations in all analyzable PDS as well as the AFX and PDS of one patient. The majority of our TP53 mutated tumors are associated with an immunohistochemical TP53 expression. However, some TP53 mutated cases were immunohistochemically negative. This discrepancy has been reported by other investigators especially in the case of nonsense, splice and null mutations [9, 10]. The majority of the detected TP53 substitutions demonstrated characteristic UV-induced TP53 mutations taking place at dipyrimidine sites being C to T transitions. This is in accordance with previous studies in UV-induced cSCC and basal cell carcinomas (BCC) [11]. All PDS investigated were located in UV-exposed localizations. Interestingly, 3 of 5 PDS (including the case with an AFX and PDS) had double-hit mutations in the TP53 gene not showing the typical C to T transitions in the second hit.

The tumor-suppressor protein TP53 is a transcriptional activator which is involved in cell-cycle control, DNA repair and apoptosis in response to a variety of stimuli. Loss of p53 functionality is known to result in impaired growth arrest and inappropriate cell survival explaining the fact that TP53 is the most frequently mutated gene in a wide range of human cancers [12–14].

Furthermore, we detected additional mutations in the CDKN2A, KNSTRN, HRAS and PIK3CA genes in a single PDS. Another activating mutation of PIK3CA gene was found in the recurring tumor. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are lipid kinases that regulate signaling pathways important in the tumorigenesis of solid and mesenchymal tumors [15–19]. Preclinical and clinical studies in patients with breast, cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancer treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors could demonstrate a higher response rate in patients with activating PIK3CA mutation than patients without mutation [20–22]. A subset of dermal sarcomas with identified activating PIK3CA mutation might therefore respond to a treatment with PI3K inhibitors.

CDKN2A mutations have been frequently detected in other UV-induced tumors as well as in few sarcomas [8, 23–25]. The double-hit mutation in CDKN2A that we detected in one case (EX1: c148C>T p.Q50* and EX2: c.442G>A p.A148T) leads to a non-functional protein. We speculate that this mutation leads to a lacking inhibition of the CCND1–CDK4/6 complexes.

The GTPase HRAS is involved in regulating cell division in response to growth factor stimulation. Our detected activating HRAS mutation has the capacity to a ligand-independent cell growth/proliferation [26, 27].

The detected KNSTRN mutation in one of our tumors is located in a UV-signature hotspot [28, 29]. Kinastrin (kinetochore-localized astrin/SPAG5 binding protein (KNSTRN)) encodes a kinetochore-associated protein that is an essential component of the mitotic spindle and is required for faithful chromosomal segregation during mitosis. It is expressed in a broad range of tissues, including skin and seems to promote genomic stability [28, 29].

Our case 7 harbored an additional isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1 mutation (EX4: c379C>T p.P127S) with unknown function. Dysfunctional IDH leads to reduced production of α-ketoglutarate and NADH and increased production of 2-hydroxyglutarate, an oncometabolite. IDH1 mutations were originally reported as frequent events in glioblastomas as well as acute myeloid leukemia [30–32].

Another new finding of our investigations is the immunohistochemical overexpression of CCND1 and/or CDK4 in 9 of 11 tumors. Therefore, deregulation of the CCND1/CDK4/6/RB1 pathway or mutations, amplifications and overexpression of the CCND1 gene are frequently observed in different malignomas including UV-related cSCC. In this context, CCND1 overexpression usually occurs early during tumorigenesis and the increased levels of CCND1 seem to result more frequently from a defective regulation at a post-translational level, rather than from a somatic mutation or rearrangement in the CCND1 gene [33–36].

Our findings of CCND1 and/or CDK4 allow us the suggestion that the selective CDK4/6 inhibitor Palbociclib (IBRANCE®, Pfizer Inc.) may be a promising treatment option in unresectable or metastasized tumor stages. Palbociclib (= PD0332991) has been approved in 2015 by the FDA for the treatment of metastasized ER+, ERBB2-negative breast cancer in postmenopausal women in combination with Letrozole [37]. Due to the fact that patients benefit from this therapy regardless of the biomarker status Palbociclib was approved for an unselected population [37].

Moreover, we saw an insulin-like growth factor II (IGF-II) mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP3) immunohistochemical overexpression in 2 of our 5 AFX and 4 of 5 analyzable PDS. There was a focally positivity in the AFX and a diffuse positivity in the PDS of the same patient. IMP3 is a member of the insulin-like growth factor II mRNA binding protein family [38]. It has been shown to be involved in tumorigenesis of certain malignant neoplasms and is correlated with worse prognosis in some carcinomas [39–45]. In regard to sarcomas, cytoplasmic IMP3 expression of varying intensity was detected in 52-100% of cutaneous leiomyosarcomas in contrast to typical leiomyomas [46]. Larger studies need to be performed to investigate if IMP3 staining may be useful for discriminating AFX from PDS in routine praxis or could be used as an indicator of a more aggressive clinical behavior in AFX (AFX with advanced tendency to PDS).

In conclusion, UV-induced mutations, especially TP53 mutations and CCND1/CDK4 alterations seem to be essential in the development of PDS. Furthermore, we found some more interesting mutated genes in other pathways (activated mutations of HRAS, PIK3CA and CDKN2A). In unresectable or metastasizing tumor stages CDK4/6 inhibitors (Palbociclib) or PI3K inhibitors (Pazopanib) seem to be promising treatment options. A targeted therapy could further be useful to size down the tumor before operation or in the case of inoperable patients.

The detection of TP53 mutations in all tumors as well as a complete identical exon mutation profile in the AFX and PDS of the same patient seems to emphasize our hypothesis that AFX is an UV-induced non-infiltrating precursor of PDS. IMP3 has probably the potential to discriminate AFX from PDS or could be used as an indicator of a more aggressive clinical behavior in AFX.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient characteristics and tumor material

11 cases (5x AFX and 6x PDS) were included into this study (see Table 3). Case 5 consisted of two tumor samples: primary: an AFX, which had been completely excised, and secondly: a PDS three years after the initial diagnosis.

Table 3. Patient and Tumor Characteristics.

| AFX (cases 1-5) | PDS (cases 5-10) | AFX and PDS of the same patient (case 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Female | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Age range; median (years) | 75-84; 81 | 66-89; 82.5 | 84 (AFX) – 87 (PDS) |

| Tumor localization - Capillitium - Thigh | 4 1 | 5 | 1 |

All tumors were selected due to their “typical” morphology, AFX had to be well-defined to the dermis in contrast to the PDS which had to present infiltration of the subcutis. Immunohistochemical stainings performed at the time of diagnosis had to include at least one cytokeratin (such as CK 5/6 or pan-cytokeratin), two melanocytic (such as S100 and melan A, HMB45) and vascular markers (such as CD31, CD34, podoplanin) to exclude other entities.

Tissue microarray (TMA)

Two tissue cores from different areas of each tumor were punched out and transferred in a TMA recipient block. TMA construction was performed as described earlier [47]. In brief, tissue cylinders with a diameter of 1.2 mm each were punched from selected tumor tissue blocks using a homemade semi-automated precision instrument and brought into empty recipient paraffin blocks. Four μm sections of the resulting TMA blocks were transferred to an adhesive coated slide system (Instrumedics Inc., Hackensack, NJ). Consecutive sections were used for fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical stainings were performed using the BOND MAX from Leica (Leica, Germany) according to the protocol of the manufacturers. For details of all antibodies see Table 4. All immunostainings were scored independently by one dermatopathologist (D.H.) and one pathologist (A.Q.).

Table 4. Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

| Antibody specificity | Species and type | Clone and Catalog No. | Source | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCND1 | Rabbit; IgG | SP4; 241R-16 | Cellmarque | EDTA; 1:25 |

| CDK4 | Mouse; IgG1 | DCS-31; AH20202 | Invitrogen | EDTA; 1:100 |

| c-MYC | Rabbit; IgG | Y69; 1472-1 | Epitomics | Citrate; 1:100 |

| CTLA-4 | Mouse; IgG1 | F-8; sc-376016 | Santa Cruz | EDTA; 1:400 |

| CTNNB1 | Rabbit; IgG | Polyclonal; RB9035-p | ThermoScientific | Citrate; 1:400 |

| EGFR | Mouse; IgG1 | 2-18C9; K1492 | Dako pharm Dx | Ready-to-use |

| EPCAM | Mouse; IgG1, K | MOC-31; 248M-16 | Cellmarque | Citrate; 1:400 |

| ERBB2 | Rabbit; IgG | 4B5; 52783600 | Ventana/Roche | Ready-to-use |

| IMP3 | Mouse; IgG2a | 69.1; M3626 | Dako | EDTA; 1:100 |

| INI-1 | Mouse; IgG2a | MRQ-27; 272M-16 | Cellmarque | EDTA; 1:100 |

| KIT | Rabbit; IgG1 | Polyclonal; A4502 | Dako | Citrate; 1:400 |

| MKI67 | Rabbit; IgG | SP6; 275R-16 | Cellmarque | EDTA; 1:100 |

| MDM2 | Mouse; IgG2b | IF2; 18-2403 | Invitrogen | EDTA; 1:100 |

| MET | Rabbit; IgG | SP44; 790-4430 | Ventana/Roche | Ready-to-use |

| p40 | Rabbit; IgG | Polyclonal; ACI3030B | Zytomed | EDTA; 1:50 |

| TP53 | Mouse; IgG2b | DO-7; M7001 | Dako | Citrate; 1:800 |

| PD-L1 | Rabbit; IgG | 28-8; Ab205921 | Abcam/Dako | EDTA; 1:100 |

| SOX2 | Rabbit; IgG | SP76; 371R-16 | Cellmarque | EDTA; 1:50 |

FISH

FGFR1 amplification analysis

A Spectrum green-labeled FGFR1-probe (8p11.23-p11.22) was used together with a Spectrum orange-labeled CEN8 probe (ZytoLight® SPEC FGFR1/CEN 8 Dual Color Probe) for FGFR1 amplification analysis as described before [48, 49].

FGFR2 and FGFR3 translocation analysis

Translocations affecting the FGFR2 gene have been investigated using FGFR2 break-apart FISH probe mix (ZytoVision, Germany), FGFR3 gene have been investigated using the ZytoLight® SPEC FGFR3 Dual Color Break Apart Probe (ZytoVision, Germany) designed to detect rearrangements involving the chromosomal region 4p16.3 - for details compare literature [50].

Next-generation-sequencing (NGS)

Tumors were diagnosed by an experienced pathologist and dermatopathologist (A.Q. and D.H.) and tumor content was defined.

All samples were fixed in neutral-buffered formalin prior to paraffin embedding (FFPE-samples). On a haematoxylin-eosin stained slide tumor areas were selected by a pathologist and dermatopathologist (A.Q. and D.H.) and DNA was extracted from three corresponding unstained 10 μm thick slides by manual micro-dissection as described before [51]. The DNA was isolated by semi-automated extraction with the Maxwell® 16 FFPE Plus Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Maxwell® 16, Promega). DNA extracts were quantified by qPCR.

Targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) was performed with an in-house specified, customized primer panel of 17 different genes (BRAF exons 11, 15; CDK4 exon 2; CDKN2A exons 1, 2; GNA11 exon 5; GNAQ exon 5; HRAS exons 2-4; IDH1 exon 4; KIT exons 9, 11, 13, 17, 18; KNSTRN exon 1; KRAS exons 2-4; NRAS exons 2-4; OXA1L exon 1, PDGFRA exons 12, 14, 18; PIK3CA exons 9, 20; PTEN exons 1-7, RAC1 exon 2, TP53 exons 5-9). Library preparation was performed with the GeneRead™ DNAseq targeted Panels V2 Kit from Qiagen.

Sequencing was done on an Illumina MiSeq benchtop sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Results were visualized in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) [6] and manually analyzed.

Quality criteria for mutation calling were a coverage >200, an allelic frequency of 5% mutated allele in a background of wildtype alleles and a tumor content of >10%. Samples that did not fulfill these criteria were excluded from this study and determined as not analyzable.

NGS was performed in 6 PDS (cases 5-10) and one AFX (Case 5: the patient who developed an AFX and PDS).

Acknowledgments

We thank Wiebke Jeske and Magdalene Fielenbach for technical assistance performing the TMA and immunohistochemical stainings. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the SFB829 (Z2 to C.M.).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: There is no conflicts of interest. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected by the approval of the institution's human research review committee (Registration No. 15-307). All subjects gave consent prior to participation in this study.

FUNDING

No extramural funding has been received for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gru AA, Santa Cruz DJ. Atypical fibroxanthoma: a selective review. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2013;30:4–12. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCalmont TH. Correction and clarification regarding AFX and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2012;39:8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luzar B, Calonje E. Morphological and immunohistochemical characteristics of atypical fibroxanthoma with a special emphasis on potential diagnostic pitfalls: a review. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2010;37:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dei Tos AP, Maestro R, Doglioni C, Gasparotto D, Boiocchi M, Laurino L, Fletcher CD. Ultraviolet-induced p53 mutations in atypical fibroxanthoma. The American journal of pathology. 1994;145:11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakamoto A, Oda Y, Itakura E, Oshiro Y, Nikaido O, Iwamoto Y, Tsuneyoshi M. Immunoexpression of ultraviolet photoproducts and p53 mutation analysis in atypical fibroxanthoma and superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Modern pathology. 2001;14:581–588. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller K, Goodlad JR, Brenn T. Pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: adverse histologic features predict aggressive behavior and allow distinction from atypical fibroxanthoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2012;36:1317–1326. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31825359e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.South AP, Purdie KJ, Watt SA, Haldenby S, den Breems NY, Dimon M, Arron ST, Kluk MJ, Aster JC, McHugh A, Xue DJ, Dayal JH, Robinson KS, Rizvi SM, Proby CM, Harwood CA, et al. NOTCH1 mutations occur early during cutaneous squamous cell carcinogenesis. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2014;134:2630–2638. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickering CR, Zhou JH, Lee JJ, Drummond JA, Peng SA, Saade RE, Tsai KY, Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Lai SY, Yu J, Muzny DM, Doddapaneni H, Shinbrot E, Covington KR, Zhang J, et al. Mutational landscape of aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clinical cancer research. 2014;20:6582–6592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havrilesky L, Darcy k M, Hamdan H, Priore RL, Leon J, Bell J, Berchuck A, Gynecologic Oncology Group S Prognostic significance of p53 mutation and p53 overexpression in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Journal of clinical oncology. 2003;21:3814–3825. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anzola M, Saiz A, Cuevas N, Lopez-Martinez M, Martinez de Pancorbo MA, Burgos JJ. High levels of p53 protein expression do not correlate with p53 mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:502–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2004.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moles JP, Moyret C, Guillot B, Jeanteur P, Guilhou JJ, Theillet C, Basset-Seguin N. p53 gene mutations in human epithelial skin cancers. Oncogene. 1993;8:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petitjean A, Achatz MI, Borresen-Dale AL, Hainaut P, Olivier M. TP53 mutations in human cancers: functional selection and impact on cancer prognosis and outcomes. Oncogene. 2007;26:2157–2165. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins CP, Brown-Swigart L, Evan GI. Modeling the therapeutic efficacy of p53 restoration in tumors. Cell. 2006;127:1323–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T. Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo. Nature. 2007;445:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes MP, Wang H, Espinal-Witter R, Douglas W, Solomon GJ, Baker SJ, Ellenson LH. PIK3CA and PTEN mutations in uterine endometrioid carcinoma and complex atypical hyperplasia. Clinical cancer research. 2006;12:5932–5935. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine DA, Bogomolniy F, Yee CJ, Lash A, Barakat RR, Borgen PI, Boyd J. Frequent mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancers. Clinical cancer research. 2005;11:2875–2878. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demicco EG, Torres KE, Ghadimi MP, Colombo C, Bolshakov S, Hoffman A, Peng T, Bovee JV, Wang WL, Lev D, Lazar AJ. Involvement of the PI3K/Akt pathway in myxoid/round cell liposarcoma. Modern pathology. 2012;25:212–221. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Je EM, An CH, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Mutational analysis of PIK3CA, JAK2, BRAF, FOXL2, IDH1, AKT1 and EZH2 oncogenes in sarcomas. APMIS. 2012;120:635–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2012.02878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choy E, Hornicek F, MacConaill L, Harmon D, Tariq Z, Garraway L, Duan Z. High-throughput genotyping in osteosarcoma identifies multiple mutations in phosphoinositide-3-kinase and other oncogenes. Cancer. 2012;118:2905–2914. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck JT, Ismail A, Tolomeo C. Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway: an emerging treatment strategy for squamous cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janku F, Wheler JJ, Westin SN, Moulder SL, Naing A, Tsimberidou AM, Fu S, Falchook GS, Hong DS, Garrido-Laguna I, Luthra R, Lee JJ, Lu KH, Kurzrock R. PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in patients with breast and gynecologic malignancies harboring PIK3CA mutations. Journal of clinical oncology. 2012;30:777–782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, Maira M, McNamara K, Perera SA, Song Y, Chirieac LR, Kaur R, Lightbown A, Simendinger J, Li T, Padera RF, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louis-Brennetot C, Coindre JM, Ferreira C, Perot G, Terrier P, Aurias A. The CDKN2A/CDKN2B/CDK4/CCND1 pathway is pivotal in well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma oncogenesis: an analysis of 104 tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50:896–907. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohseny AB, Tieken C, van der Velden PA, Szuhai K, de Andrea C, Hogendoorn PC, Cleton-Jansen AM. Small deletions but not methylation underlie CDKN2A/p16 loss of expression in conventional osteosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:1095–1103. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho A, Dowdy SF. Regulation of G(1) cell-cycle progression by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(01)00263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu CX, Li XY, Li CF, Chen YZ, Cui XB, Hu JM, Li F. Compound HRAS/PIK3CA mutations in Chinese patients with alveolar rhabdomyosarcomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1771–1774. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.4.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauerer A, Herschberger E, Dietmaier W, Landthaler M, Hafner C. Low incidence of EGFR and HRAS mutations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas of a German cohort. Experimental dermatology. 2011;20:848–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee CS, Bhaduri A, Mah A, Johnson WL, Ungewickell A, Aros CJ, Nguyen CB, Rios EJ, Siprashvili Z, Straight A, Kim J, Aasi SZ, Khavari PA. Recurrent point mutations in the kinetochore gene KNSTRN in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Nature genetics. 2014;46:1060–1062. doi: 10.1038/ng.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaju PD, Nguyen CB, Mah AM, Atwood SX, Li J, Zia A, Chang AL, Oro AE, Tang JY, Lee CS, Sarin KY. Mutations in the Kinetochore Gene KNSTRN in Basal Cell Carcinoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2015;135:3197–3200. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yan H, Parsons DW, Jin G, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Yuan W, Kos I, Batinic-Haberle I, Jones S, Riggins GJ, Friedman H, Friedman A, Reardon D, Herndon J, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:765–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abbas S, Lugthart S, Kavelaars FG, Schelen A, Koenders JE, Zeilemaker A, van Putten WJ, Rijneveld AW, Lowenberg B, Valk PJ. Acquired mutations in the genes encoding IDH1 and IDH2 both are recurrent aberrations in acute myeloid leukemia: prevalence and prognostic value. Blood. 2010;116:2122–2126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-250878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Wahab O, Manshouri T, Patel J, Harris K, Yao J, Hedvat C, Heguy A, Bueso-Ramos C, Kantarjian H, Levine RL, Verstovsek S. Genetic analysis of transforming events that convert chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms to leukemias. Cancer research. 2010;70:447–452. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin M, Inoue S, Umemura T, Moriya J, Arakawa M, Nagashima K, Kato H. Cyclin D1, p16 and retinoblastoma gene product expression as a predictor for prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer at stages I and II. Lung cancer. 2001;34:207–218. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gansauge S, Gansauge F, Ramadani M, Stobbe H, Rau B, Harada N, Beger HG. Overexpression of cyclin D1 in human pancreatic carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. Cancer research. 1997;57:1634–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold A, Papanikolaou A. Cyclin D1 in breast cancer pathogenesis. Journal of clinical oncology. 2005;23:4215–4224. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen Y, Xu J, Jin J, Tang H, Liang J. Cyclin D1 expression in Bowen's disease and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:545–548. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner NC, Ro J, Andre F, Loi S, Verma S, Iwata H, Harbeck N, Loibl S, Huang Bartlett C, Zhang K, Giorgetti C, Randolph S, Koehler M, Cristofanilli M. Palbociclib in Hormone-Receptor-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;373:209–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monk D, Bentley L, Beechey C, Hitchins M, Peters J, Preece MA, Stanier P, Moore GE. Characterisation of the growth regulating gene IMP3, a candidate for Silver-Russell syndrome. Journal of medical genetics. 2002;39:575–581. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.8.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoffmann NE, Sheinin Y, Lohse CM, Parker AS, Leibovich BC, Jiang Z, Kwon ED. External validation of IMP3 expression as an independent prognostic marker for metastatic progression and death for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2008;112:1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu D, Vohra P, Chu PG, Woda B, Rock KL, Jiang Z. An oncofetal protein IMP3: a new molecular marker for the detection of esophageal adenocarcinoma and high-grade dysplasia. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2009;33:521–525. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31818aada9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng W, Yi X, Fadare O, Liang SX, Martel M, Schwartz PE, Jiang Z. The oncofetal protein IMP3: a novel biomarker for endometrial serous carcinoma. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2008;32:304–315. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181483ff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sitnikova L, Mendese G, Liu Q, Woda BA, Lu D, Dresser K, Mohanty S, Rock KL, Jiang Z. IMP3 predicts aggressive superficial urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Clinical cancer research. 2008;14:1701–1706. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao B, Hu Y, Herrick DJ, Brewer G. The RNA-binding protein IMP-3 is a translational activator of insulin-like growth factor II leader-3 mRNA during proliferation of human K562 leukemia cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:18517–18524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Z, Chu PG, Woda BA, Liu Q, Balaji KC, Rock KL, Wu CL. Combination of quantitative IMP3 and tumor stage: a new system to predict metastasis for patients with localized renal cell carcinomas. Clinical cancer research. 2008;14:5579–5584. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi M, Fraire AE, Chu P, Cornejo K, Woda BA, Dresser K, Rock KL, Jiang Z. Oncofetal protein IMP3, a new diagnostic biomarker to distinguish malignant mesothelioma from reactive mesothelial proliferation. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2011;35:878–882. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318218985b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornejo K, Shi M, Jiang Z. Oncofetal protein IMP3: a useful diagnostic biomarker for leiomyosarcoma. Human pathology. 2012;43:1567–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simon R, Mirlacher M, Sauter G. Tissue microarrays. Methods Mol Med. 2005;114:257–268. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-923-0:257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schildhaus HU, Heukamp LC, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Riesner K, Schmitz K, Binot E, Paggen E, Albus K, Schulte W, Ko YD, Schlesinger A, Ansen S, Engel-Riedel W, Brockmann M, Serke M, Gerigk U, et al. Definition of a fluorescence in-situ hybridization score identifies high- and low-level FGFR1 amplification types in squamous cell lung cancer. Modern pathology. 2012;25:1473–1480. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schildhaus HU, Nogova L, Wolf J, Buettner R. FGFR1 amplifications in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2013;2:92–100. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2013.03.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graham RP, Barr Fritcher EG, Pestova E, Schulz J, Sitailo LA, Vasmatzis G, Murphy SJ, McWilliams RR, Hart SN, Halling KC, Roberts LR, Gores GJ, Couch FJ, Zhang L, Borad MJ, Kipp BR. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 translocations in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Human pathology. 2014;45:1630–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ihle MA, Fassunke J, Konig K, Grunewald I, Schlaak M, Kreuzberg N, Tietze L, Schildhaus HU, Buttner R, Merkelbach-Bruse S. Comparison of high resolution melting analysis, pyrosequencing, next generation sequencing and immunohistochemistry to conventional Sanger sequencing for the detection of p.V600E and non-p.V600E BRAF mutations. BMC cancer. 2014;14:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahl C, Christensen C, Jonsson G, Lorentzen A, Skjodt ML, Borg A, Pawelec G, Guldberg P. Mutual exclusivity analysis of genetic and epigenetic drivers in melanoma identifies a link between p14 ARF and RARbeta signaling. Molecular cancer research. 2013;11:1166–1178. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oki K, Takita J, Hiwatari M, Nishimura R, Sanada M, Okubo J, Adachi M, Sotomatsu M, Kikuchi A, Igarashi T, Hayashi Y, Ogawa S. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are rare in pediatric myeloid malignancies. Leukemia. 2011;25:382–384. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]