Abstract

Advance directives (AD) were developed to respect patient autonomy. However, very few patients have AD, even in cases when major cardiovascular surgery is to follow. To understand the reasons behind the low prevalence of AD and to help decision making when patients are incompetent, it is necessary to focus on the impact of prehospital practitioners, who may contribute to an increase in AD by discussing them with patients. The purpose of this study was to investigate self-rated communication skills and the attitudes of physicians potentially involved in the care of cardiovascular patients toward AD.

Self-administered questionnaires were sent to general practitioners, cardiologists, internists, and intensivists, including the Quality of Communication Score, divided into a General Communication score (QOCgen 6 items) and an End-of-life Communication score (QOCeol 7 items), as well as questions regarding opinions and practices in terms of AD.

One hundred sixty-four responses were received. QOCgen (mean (±SD)): 9.0/10 (1.0); QOCeol: 7.2/10 (1.7). General practitioners most frequently start discussions about AD (74/149 [47%]) and are more prone to designate their own specialty (30/49 [61%], P < 0.0001). Overall, only 57/159 (36%) physicians designated their own specialty; 130/158 (82%) physicians ask potential cardiovascular patients if they have AD and 61/118 (52%) physicians who care for cardiovascular patients talk about AD with some of them.

The characteristics of physicians who do not talk about AD with patients were those who did not personally have AD and those who work in private practices.

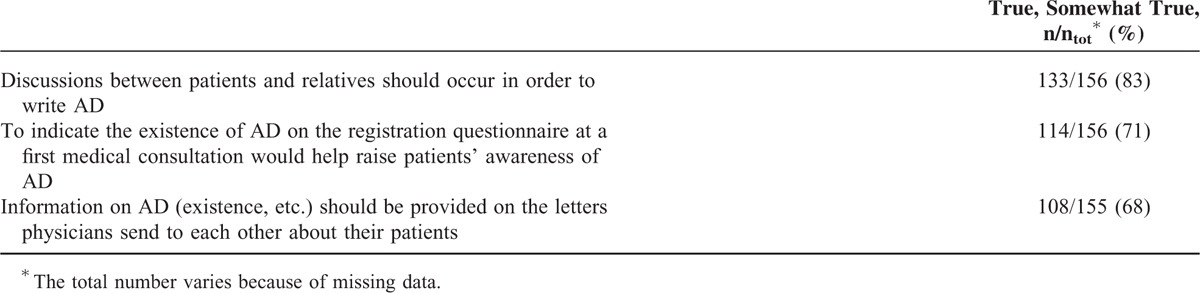

One hundred thirty-three (83%) physicians rated the systematic mention of patients’ AD in the correspondence between physicians as good, while 114 (71%) at the patients’ first registration in the private practice.

Prehospital physicians rated their communication skills as good, whereas end-of-life communication was rated much lower. Only half of those surveyed speak about AD with cardiovascular patients. The majority would prefer that physicians of another specialty, most frequently general practitioners, initiate conversation about AD. In order to increase prehospital AD incidence, efforts must be centered on improving practitioners’ communication skills regarding death, by providing trainings to allow physicians to feel more at ease when speaking about end-of-life issues.

INTRODUCTION

Advance directives (AD) were developed to respect patient autonomy in the prospect of care for incompetent patients. The principle of patient autonomy changed the physician–patient relationship. While the historical paternalistic model depends on the good will and knowledge of the practitioner, who seeks the welfare of patients considered too vulnerable to do so because of their illness, the shared decision-making model acknowledges differences between patients, in terms of needs and desires. It thus requires a new form of communication between the physician and the patient.1–3 Improving communication with the family also contributes to improving patient care and family satisfaction.4,5

Even though this type of relationship is widely recognized as the best practice, certain pitfalls in achieving physician–patient dialog have been identified. Little room for physician–patient discussions due to time constraints, as well as financial and organizational barriers have been reported.6–8 Physicians tend to underestimate patient needs for information and overestimate patient understanding and awareness of their prognosis.9,10 Discrepancies between patient self-reported and physician diagnoses serve to illustrate the communication difficulties which exist in a basic therapeutic relationship.11 Moreover, culture is an influencing factor which modifies patient expectations and preferences, this must be taken into consideration when discussing advance care planning.1 While having a primary care physician is associated with a greater likelihood of having AD,12 it has also been reported that not all patients with AD have informed their doctors about the existence of the latter.13 In literature, internists and primary care physicians are often cited as central in advance care planning processes.14

Since many patients and their family members are unfamiliar with the medical setting, information and help in the writing of AD should be provided.15,16 With regard to surgery, literature mentions that the discussion of possible postoperative complications and a prolonged intensive care unit stay is necessary to allow for meticulous informed consent. This process must be well documented.13,17 Nevertheless, the number of patients AD for whom surgery is planned is low—around 20%.18–20 More generally in acute care, the prevalence of advance care planning ranges from 1% to 44%.12,21 To palliate the lack of AD in a perioperative setting, some researchers propose to hold anticipatory multidisciplinary AD team discussions with patients/surrogates, anesthetists, surgeons, and intensivists22 and to integrate supportive care.23–27

The discrepancy between the theoretical usefulness reported in literature and the lack of AD in practice lead to the present study. The opinions of prehospital practitioners involved in care of patients before major cardiovascular surgery is of particular interest. Indeed, heart surgery is perceived as a vital operation, despite a low mortality rate between 2% and 5%.28 Thus, physicians involved in the care of cardiovascular patients may have the opportunity to discuss these topics preoperatively.23,29,30 This study investigates physician self-rated communication skills, their opinions, as well as the prevalence of discussions about AD in practice with patients in a preoperative setting, prior to major cardiovascular surgery. The results are expected to offer new insight and solutions by encouraging communication among physicians of different specialties, as well as between physicians, patients, and families.

METHODS

General practitioners (GP), internists, cardiologists, and intensivists in Geneva, Switzerland, were enrolled in the study. In April 2009, they were sent a letter explaining the study, an anonymous questionnaire and a prepaid return envelope. A code allowed the sending of reminders (after 2 months, up to 6 months). Methods regarding the development of the questionnaire are described elsewhere.31 Demographic data were asked for at the end of the questionnaire. Several questions allowed comments and are used to illustrate the results.

Communication skills were explored using the validated Quality of Communication score (QOC).32 Opinions about AD communication were investigated by means of the following questions: “In theory, would you ask potential cardiovascular patient about AD?”, “Who should start a discussion about AD with cardiovascular patients?,” and “Who should help write AD?” The prevalence of discussions about AD in practice was evaluated by means of the proportion of overall patients and cardiovascular patients with whom physicians talked about AD. The usefulness of AD, the wish to help cardiovascular patients in writing AD and the reasons why, reported elsewhere,31 were also compared to the communication scores and the physicians’ opinions.

The original version of the validated QOC for patients was modified for physicians, and was translated forward and backwards from English to French to reach equilibrium. The 13-item QOC is a self-administered questionnaire divided into a General Communication score (QOCgen, 6 items about attention, listening, vocabulary, and eye-contact) and an End-of-Life Communication score (QOCeol, 7 items regarding feelings concerning sickness, end-of-life and death, respect, and patient implication in care). The scale ranges from 0 (poorest) to 10 (best quality of communication).33

Ethical Approval

The protocol was approved by the Geneva University Hospitals Ethics Committee (NAC 09-001) on November 23, 2009. A returned questionnaire validated the informed consent of the participant.

Statistical Analysis

StatView for Windows version 5.0.1® (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata Statistical Software, Release 8.0® (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX) were used. Univariate analyses were performed to identify factors associated with data regarding physicians’ opinions and practice.

Data were compared using univariate logistic regression (categorical variables) and Fischer or Chi-squared tests as suitable. Results are expressed as proportions, odds ratios (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values as (nx/ny [%] vs nz/nw [%], OR [95% CI] P).

Results of the QOC are expressed for all items and the 2 subscores as mean (±SD). The 2 subscores were compared using a linear regression and significant differences were compared with other results using the unpaired T-test or ANOVA.

RESULTS

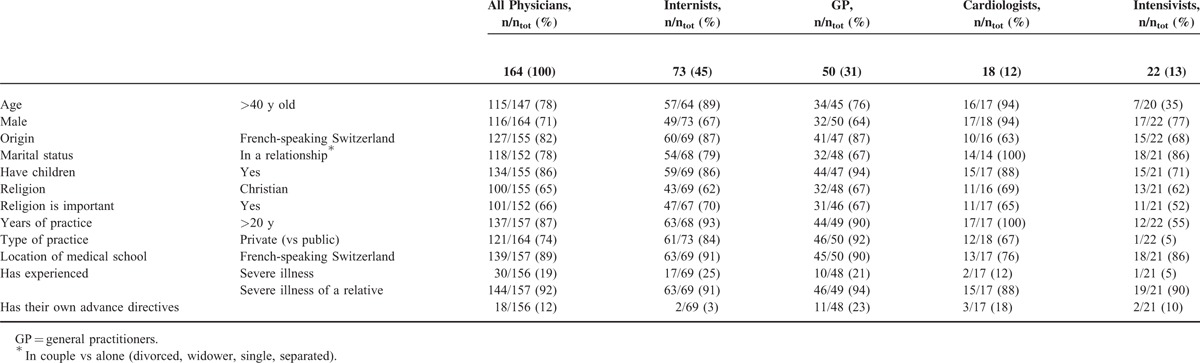

Out of 409 questionnaires sent, 172 were returned (42%) and 164 filled out completely (40%). The personal and professional characteristics of those who responded were divided into medical specialties as described in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Physicians’ Personal and Professional Characteristics Divided into Medical Specialties

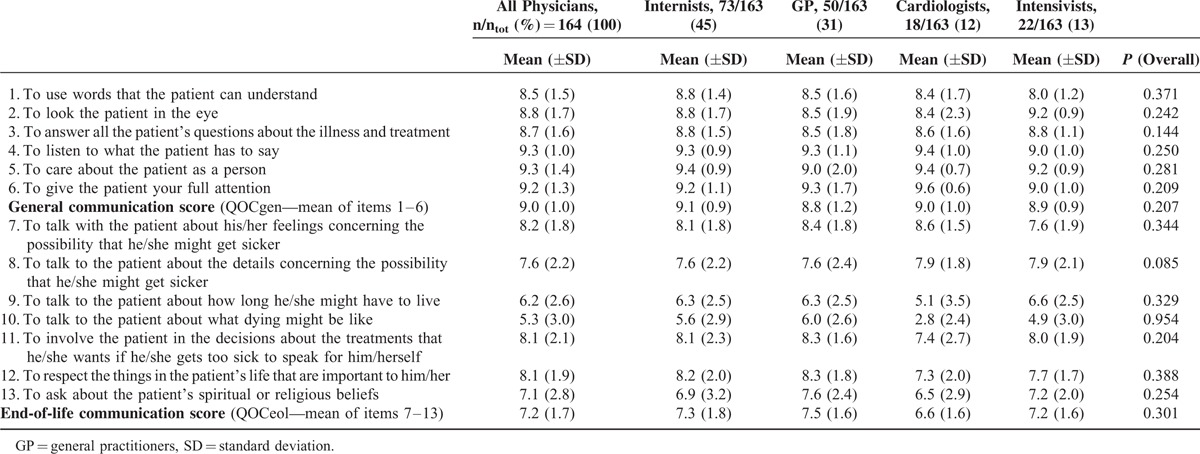

The self-rated QOC score, divided into the General Communication subscore (QOCgen) and the End-of-life Communication subscore (QOCeol), are reported in Table 2. The QOCgen was generally rated higher (better communication) than the QOCeol (P < 0.001). The linear regression between the 2 subscores was low (r2 = 0.17).

TABLE 2.

Physicians’ Self-Rated Quality of Communication: Individual Items and Subscores (General and End-of-Life Communication)

Physician rated QOCgen was higher when they had experienced a severe illness themselves (mean ± SD: 9.3 ± 0.7 vs 8.9 ± 1.1, P = 0.03). No demographic characteristic was associated with the communication scores. Cardiologists rated their ability to talk about what dying might be (item 10) significantly worse than other physicians (2.8 ± 2.4 vs 5.6 ± 2.8, P < 0.001).

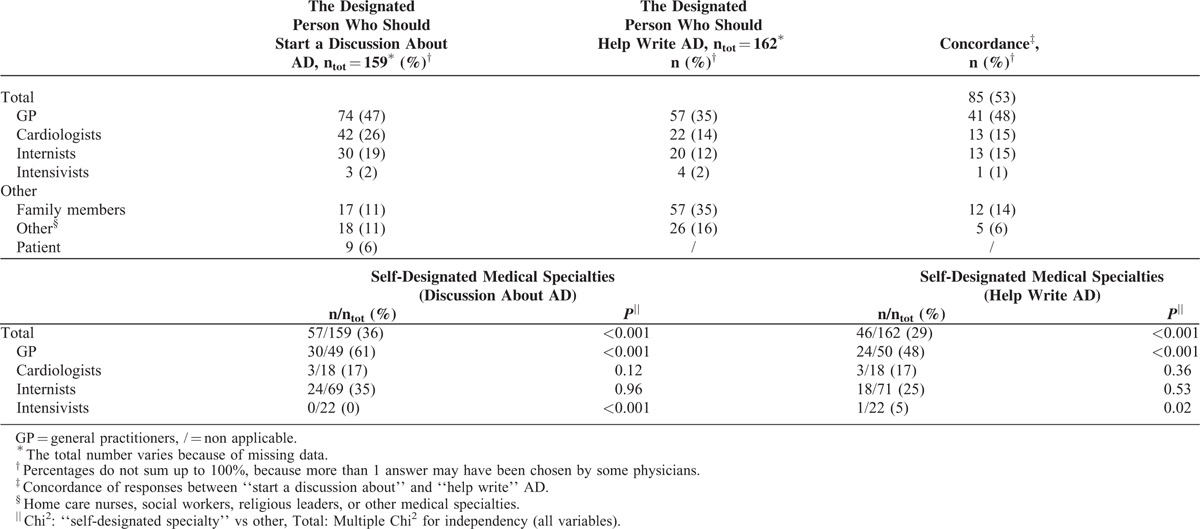

Table 3 describes physician opinions on who should start a discussion about AD with cardiovascular patients and help them write AD, as well as the percentages of physicians who designated their own medical specialty. Cardiologists tended to designate family members as those who should start the discussion regarding AD (6/18 [33%] vs 11/140 [8%], OR 5.86 [1.84–18.66], P < 0.01), more so than other specialties. The scores of QOCeol of those who designated their own medical specialty to help write AD were higher when compared to others (7.7 ± 1.6 vs 7.0 ± 1.7, P < 0.05). Some comments on the returned questionnaires clearly stated that, “this is not the role of a specialist,” while others expressed that this role belongs to cardiologists or anesthetists.

TABLE 3.

Physicians’ Opinion on Who Should Start a Discussion and Help Write Advance Directives (AD), Their Concordance, and the Self-Designated Medical Specialty

In theory, 130/158 (82%) physicians would ask potential cardiovascular patients if they have AD, 101 (64%) would ask for a copy for the medical record, 81 (51%) would ask if the AD are still accurate, and 78 (49%) would ask who the holder is. None of these opinions correlated with demographic data or with communication scores.

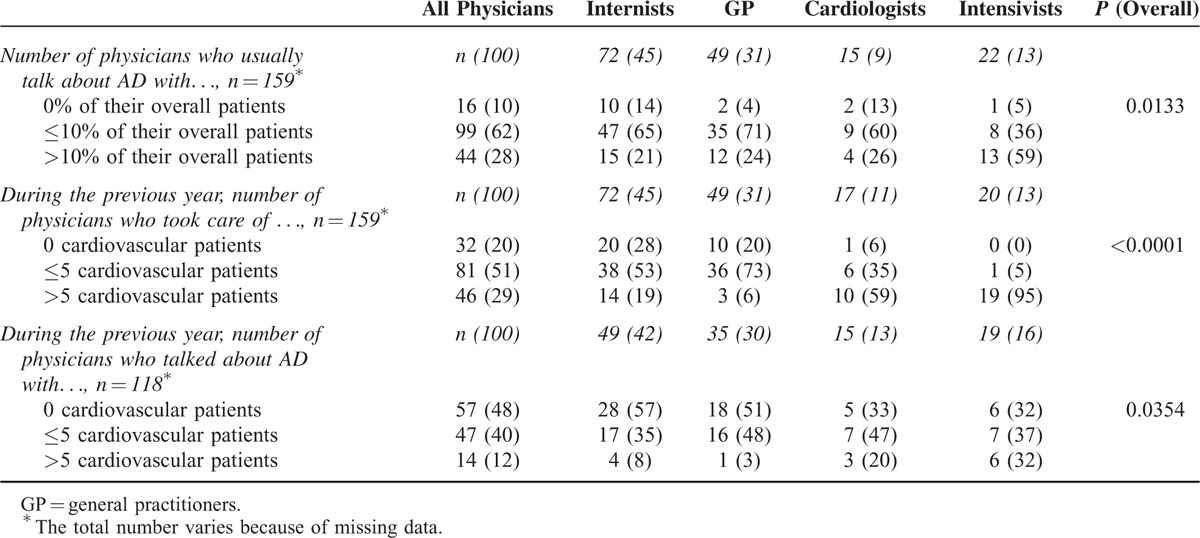

Table 4 explores the prevalence of physicians’ discussions about AD in practice: the number of physicians who talked about AD to all and specifically cardiovascular patients, as well as the number of physicians who were involved in treating cardiovascular patients during the previous year. Physicians who did not meet cardiovascular patients did not answer differently from the others. Out of the 143/159 (90%) physicians who talked about AD with some of their overall patients, 127/159 (80%) met cardiovascular patients, of whom 61/118 (52%) talked about AD. Physicians who talked about AD with more than 10% of their patients or with more than 5 of their cardiovascular patients in the previous year were significantly more often working in public practices (20/44 [45%] vs 21/115 [18%], OR 3.70 [1.76–7.75], P < 0.001 and 8/14 [57%] vs 25/104 [24%], OR 4.21 [1.33–13.31], P = 0.02, respectively). The QOCeol was rated higher by physicians who talked with more than 5 cardiovascular patients (8.0 ± 1.7 vs 7.0 ± 1.6, P < 0.001). There was no correlation with the QOCgen scores.

TABLE 4.

Number of Physicians Who Talked About Advance Directives (AD) to All and Cardiovascular Patients, and Who Were Involved in Treating Cardiovascular Patients the Previous Year

In the restricted group of the 127 physicians who met cardiovascular patients, physicians who said they did not talk about AD with them tended not to have personal AD (48/99 [48%] vs 11/14 [79%], OR 0.26 [0.07–0.98], P < 0.05), worked less often in public practices (11/57 [19%] vs 22/61 [36%], OR 0.42 [0.18–0.98], P < 0.05) and tended less to ask potential cardiovascular patients if they have AD (41/57 [72%] vs 54/61 [89%], OR 0.33 [0.13–0.88], P = 0.04). No other demographic data correlated with this result, the communication scores neither.

Amidst the 127 physicians, lack of interest regarding AD was associated to poorer QOCeol. Indeed, the physicians who did not think that AD were useful, those who did not personally want to help cardiovascular patients write AD, and those who would not ask potential cardiovascular patients if they have AD, had lower QOCeol scores (mean ± SD: 6.4 ± 1.7 vs 7.4 ± 1.7, P = 0.02; 6.0 ± 1.9 vs 7.60 ± 1.75, P < 0.001; and 6.3 ± 1.4 vs 7.4 ± 1.7, P < 0.001, respectively). Among the physicians who did not personally want to help cardiovascular patients write AD, those who stated that they had not given enough thought to AD and those who said that they lacked training had lower QOCeol scores (5.5 ± 1.9 vs 7.4 ± 1.0, P = 0.01 and 5.2 ± 2.2 vs 6.9 ± 1.3, P = 0.03, respectively). None of these opinions was significantly associated with the QOCgen score.

Table 5 summarizes physician views on propositions regarding how communication and implementation of AD may be improved in a medical setting. Physicians working in public practice manifested a preference for the mention of AD in the correspondence between colleagues (33/41 [80%] vs 75/119 [63%], OR 2.42 [1.03–5.70], P = 0.04). Some relevant comments illustrated that, “Several patients were seriously shocked and destabilized when on arrival in a hospital service they were asked straightaway if they wanted to be resuscitated etc., whereas they came to be looked after.” “Several patients were hurt to have to fill AD at their entry to the hospital. They felt at once threatened, independently of the severity of their disorder. It was felt as a kind of legal cover so that the physicians would not be prosecuted.”

TABLE 5.

Physicians’ Views on How Implementation of AD Could Be Improved in a Medical Setting

DISCUSSION

The physicians involved in the study rated their general communication skills (QOCgen) as high, while evaluating their end-of-life communication skills (QOCeol) as lower. The personal experience of a severe illness was associated with a higher QOCgen score, which suggests that this may favor the development of communication skills. Cardiologists rated their QOCeol as lower when compared to other specialties, especially when discussing death. This finding is surprising since they are in the front line of care for patients with cardiovascular diseases, that are among the leading causes of death worldwide (WHO).34

The majority of physicians in this study selected a doctor as the person who should start a discussion with a cardiovascular patient about AD. This converges with literature that says that the role of the physician is to support and help translate patient preferences into clinical care.14,35,36 The GP, who were the most keen to designate their own medical specialty to start the discussion, were more often chosen as the best specialty by all physicians, as previously reported.13,37 It is remarkable that cardiologists were designated as the second most apt, while they were the least keen to do so and tended to think that a family member would be the best person. In contrast to literature which proposes nurses as key persons in increasing the number of AD, they were not often referred to in this study.38,39 The most frequently designated persons to help patients write AD were GP, as often as family members. Also, most physicians recognized discussions regarding AD between patients and their relatives as important. This attitude is in line with an effective family-centered approach.30,35 Furthermore, primary care physicians have recently been encouraged to incorporate discussion and facilitation of AD in their regular patient check-ups.40 They should routinely ask the patient or the patient's family about any possible wishes concerning the end of the patient's life.41 Improved prehospital communication is paramount to prevent patient shock upon hospital admission, when they are required to discuss AD, and to improve the comprehension of patients’ wishes.42 This could increase the incidence of AD and hence, help hospital physicians when making decisions, while providing at the same time the desired intensity of care to both patients and families.35 Thus, every medical specialty should feel concerned by providing information on AD13,17 and real communication among physicians is needed in order to provide patients with information and help. According to a majority of those who responded, it would be helpful to systematically ask patients if they have AD by means of a registration questionnaire at a first consultation and to routinely state AD information in letters between colleague physicians.

If a majority of physicians were to ask potential cardiovascular patients if they have AD, only a minority would raise concrete questions (about accuracy, a copy for the medical record, etc.) to get useful information in case patients lose their competency. In practice, as many as 10% of those who responded did not talk about AD with their patients, a figure even higher when considering cardiovascular patients, at almost 50%.43,44 These results indicate that there is a huge gap between the opinion on AD and the efforts put toward their implementation. In another study, physicians’ personal and professional experience with advance care planning contributed to increase the low number of discussions occurring with patients.45 In the present study, having AD and working in public practices were associated with discussing AD with cardiovascular patients. Moreover, physicians who rated their QOCeol lower felt less comfortable with speaking about AD and providing help. They acknowledged, “not having thought enough about AD” and “lacking training” to speak about AD as reasons. Discomfort with discussing AD was a clear barrier identified in literature.31,46 Effective communication requires specialized skills and attitudes.17,47 Carr48 propose to use others’ deaths as a starting point for discussions about AD. While bioethicists and physicians propose algorithms to help advance care planning,49 others think that this concerns education: citizens’ about illnesses and death,35 and physicians’ about developing comfort and skills when dealing with AD, whether at medical school or by means of postgraduate trainings, with special attention paid to private practice practitioners.40,50 Primary care physicians have recently been proposed to educate patients and their family members.42 Politics should encourage patients to seek medical advice.42 Rendering AD visible for the many patients and certain health professionals who are still unaware of what they are is utterly needed.31,51

LIMITATIONS

The low response rate and the fact this is a single-centered study are limitations which are described elsewhere.31 The QOC score has been developed for patients to rate their physicians. Since no specific tool existed for physicians, this score was adapted. As the questionnaire was self-rated, the results could be biased. Indeed, patients and relatives gave their physician lower scores in literature.33,52 Also, the French version of the questionnaire was translated from the English version, according to internationally recognized guidelines that involve a forward/backward translation process and cognitive debriefing. Furthermore, depending on the rate of activity, the physician may meet a different number of cardiovascular patients. In addition, the study was lead in 2009 and the relevance of the findings could be limited. However, no public debate or important intervention took place in the meantime and the physicians’ population has not changed significantly. Finally, even though the study focused on a population of cardiovascular patients, as the physicians who did not have such patients did not answer differently from others, the conclusions drawn could also be applied to other types of patients.

CONCLUSION

Prehospital physicians rated their communication skills as good, whereas end-of-life communication was rated much lower, and only half speak about AD with their cardiovascular patients. Physicians’ characteristics associated with poor communication in advance care planning were being a cardiologist, working in private practice, having no personal AD, and lacking interest, training, or thought about AD. Physicians, whether specialists or GP, were designated to discuss about and help patients with AD; the family members could help too. Ways to increase prehospital incidence of AD and thus help physicians at the time of decisions, would be to fill the gap between the theoretical interest for AD and the practical implementation. Specific trainings at medical school and/or at postgraduate level regarding end-of-life issues may allow physicians to feel more at ease when speaking with patients and their families about death and AD in particular. Simple improvements such as systematic mention of information on patient AD in correspondence between practitioners and in the registration questionnaire at the first meeting in private practices have been proposed. Also, taking information about AD accuracy, the contact person and a copy for the medical record should be a routine process. Further research on the practical implementation of such measures is needed.

Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to Ms Fabienne Scherer and Dr Christophe Combescure, PhD, for their help.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AD = advance directives, GP = general practitioners, QOC = Quality of Communication score, QOCeol = End-of-Life Communication score, QOCgen = General Communication score.

FG conceived the design of the study, participated in the collection of data, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the article. PM participated in the design of the study, helped in performing the statistical analysis and with the data interpretation and manuscript revision. BR conceived the design of the study, helped in interpreting the data and in writing the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding for this study was provided by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation for the submitted work (Grant No: CR31I3_127135).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Frost DW, Cook DJ, Heyland DK, et al. Patient and healthcare professional factors influencing end-of-life decision-making during critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care Med 2011; 39:1174–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curtis JR. Communicating about end-of-life care with patients and families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin 2004; 20:363–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whetstine LM. Advanced directives and treatment decisions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2007; 11:150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2008; 36:953–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA 2005; 294:359–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keary S, Moorman SM. Patient-Physician End-of-Life Discussions in the Routine Care of Medicare Beneficiaries. J Aging Health 2015; 27:983–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Revelly JP, Zuercher-Zenklusen R, Chiolero R. To integrate patient's preferences in intensive care treatment plans. Rev Med Suisse 2005; 1:2912–2915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, et al. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:1690–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Discrepant perceptions about end-of-life communication: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 34:190–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox K, Britten N, Hooper R, et al. Patients’ involvement in decisions about medicines: GPs’ perceptions of their preferences. Br J Gen Pract 2007; 57:777–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schubart JR, Toran L, Whitehead M, et al. Informed decision making in advance care planning: concordance of patient self-reported diagnosis with physician diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21:637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oulton J, Rhodes SM, Howe C, et al. Advance directives for older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2015; 18:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker M, Jaspers B, King C, et al. Did you seek assistance for writing your advance directive? A qualitative study. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010; 122:620–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahia CL, Blais CM. Primary palliative care for the general internist: integrating goals of care discussions into the outpatient setting. Ochsner J 2014; 14:704–711. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin J. Actualité des directives anticipées: pas seulement en fin de vie. Rev Med Suisse 2009; 5:2474a–2475a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azoulay E, Sprung CL. Family-physician interactions in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2004; 32:2323–2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds S, Cooper AB, McKneally M. Withdrawing life-sustaining treatment: ethical considerations. Surg Clin North Am 2007; 87:919–936.viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pecanac KE, Kehler JM, Brasel KJ, et al. It's big surgery: preoperative expressions of risk, responsibility, and commitment to treatment after high-risk operations. Ann Surg 2014; 259:458–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradley CT, Brasel KJ, Schwarze ML. Physician attitudes regarding advance directives for high-risk surgical patients: a qualitative analysis. Surgery 2010; 148:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Justinger C, Richter S, Moussavian MR, et al. Advance health care directives as seen by surgical patients. Chirurg 2009; 80:455–456.458–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roger C, Morel J, Molinari N, et al. Practices of end-of-life decisions in 66 southern French ICUs 4 years after an official legal framework: a 1-day audit. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2015; 34:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ewanchuk M, Brindley PG. Perioperative do-not-resuscitate orders—doing “nothing” when “something” can be done. Crit Care 2006; 10:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swetz KM, Freeman MR, AbouEzzeddine OF, et al. Palliative medicine consultation for preparedness planning in patients receiving left ventricular assist devices as destination therapy. Mayo Clin Proc 2011; 86:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2014; 42:2418–2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson JE, Mathews KS, Weissman DE, et al. Integration of palliative care in the context of rapid response: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU advisory board. Chest 2015; 147:560–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanner CE, Fromme EK, Goodlin SJ. Ethics in the treatment of advanced heart failure: palliative care and end-of-life issues. Congest Heart Fail 2011; 17:235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemond L, Allen LA. Palliative care and hospice in advanced heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2011; 54:168–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P. Regional differences in surgical heart valve disease in Europe: comparison between northern and southern subsets of the EuroSCORE database. J Heart Valve Dis 2003; 12:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song MK, Kirchhoff KT, Douglas J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial to improve advance care planning among patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Med Care 2005; 43:1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimaldo DA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Jurson T, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of advanced care planning discussions during preoperative evaluations. Anesthesiology 2001; 95:43–50.discussion 45A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gigon F, Merlani P, Ricou B. Swiss physicians’ perspectives on advance directives in elective cardiovascular surgery. Minerva Anestesiol 2015; 81:1061–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR. Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2006; 9:1086–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long AC, Engelberg RA, Downey L, et al. Race, income, and education: associations with patient and family ratings of end-of-life care and communication provided by physicians-in-training. J Palliat Med 2014; 17:435–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO. World Health Organization (WHO) statistics. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ Accessed June 17, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin DK, Emanuel LL, Singer PA. Planning for the end of life. Lancet 2000; 356:1672–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Sullivan R, Mailo K, Angeles R, et al. Advance directives: survey of primary care patients. Can Fam Physician 2015; 61:353–356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lawrence JF. The advance directive prevalence in long-term care: a comparison of relationships between a nurse practitioner healthcare model and a traditional healthcare model. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2009; 21:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinderer KA, Lee MC. Assessing a nurse-led advance directive and advance care planning seminar. Appl Nurs Res 2013; 27:84–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petty K, DeGarmo N, Aitchison R, et al. Ethical considerations in resuscitation. Dis Mon 2013; 59:217–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Pasman HR, et al. Attitudes of physicians, nurses and relatives towards end-of-life decisions concerning nursing home patients with dementia. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 61:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nauck F, Becker M, King C, et al. To what extent are the wishes of a signatory reflected in their advance directive: a qualitative analysis. BMC Med Ethics 2014; 15:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torke AM, Siegler M, Abalos A, et al. Physicians’ experience with surrogate decision making for hospitalized adults. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24:1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torke AM, Moloney R, Siegler M, et al. Physicians’ views on the importance of patient preferences in surrogate decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010; 58:533–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snyder S, Hazelett S, Allen K, et al. Physician knowledge, attitude, and experience with advance care planning, palliative care, and hospice: results of a primary care survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013; 30:419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans N, Bausewein C, Menaca A, et al. A critical review of advance directives in Germany: attitudes, use and healthcare professionals’ compliance. Patient Educ Couns 2012; 87:277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Curtis JR, Vincent JL. Ethics and end-of-life care for adults in the intensive care unit. Lancet 2010; 376:1347–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carr D. “I don’t want to die like that ...”: the impact of significant others’ death quality on advance care planning. Gerontologist 2012; 52:770–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Messinger-Rapport BJ, Baum EE, Smith ML. Advance care planning: beyond the living will. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:276–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grossman D. Advance care planning is an art, not an algorithm. Cleve Clin J Med 2009; 76:287–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Etheridge Z, Gatland E. When and how to discuss “do not resuscitate” decisions with patients. BMJ 2015; 350:h2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 310:2271–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]