Abstract

Background:

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) is a potent immune-inflammatory mediator involved in the regulation of bone resorption. The single nucleotide polymorphism G-308A in the TNF-α gene increases the level of this cytokine. This phenomenon is also related to several diseases. Although the association between TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and dental peri-implant disease has been investigated, results have remained controversial. Hence, we performed this meta-analysis to provide a comprehensive and systematic conclusion on this topic.

Methods:

We performed a systematic literature search in PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure until July 2015. A fixed-effect model was established to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The calculated values were then used to assess the strength of the association between the TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and the dental peri-implant disease risk. The heterogeneity between included studies was evaluated with Cochran Q and I2 statistics. Interstudy publication bias was investigated with a funnel plot.

Results:

Six eligible studies were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled ORs did not reveal a significant relationship between the TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and the disease susceptibility. Subgroup analyses in terms of ethnicity and disease type yielded similar results.

Conclusion:

Our meta-analysis revealed that TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism was not significantly associated with the risk of dental peri-implant disease. However, further studies with large sample sizes should be performed to verify these results.

Keywords: dental peri-implant disease, implant failure, implant loss, marginal bone loss, peri-implantitis, TNF-α

1. Introduction

Dental osseointegrated implants are widely accepted as effective and predictable treatments in the functional and aesthetic restorations of missing teeth.[1,2] Despite the high success and survival rates of dental implants, peri-implant diseases, including marginal bone loss, peri-implantitis, and implant loosening, occur.[3,4] As a common complication in dental implants, peri-implantitis is triggered by bacterial infection, followed by a series of destructive inflammatory processes affecting the soft and hard tissues around osseointegrated implants, peri-implant pocket formation, and attachment loss, supporting bone loss, and implant loss or implant failure.[5–7] The implant success rate may be affected by multiple factors, such as implant material properties (shape, length, and surface texture), surgery-related aspects (surgical trauma and surgeon's experiences), and host-related risk factors (systemic disease, smoking habit, oral hygiene, and alveolar bone quality).[8–11] Although implant materials science and surgical techniques have substantially improved, implant failures occur on some patients who are exposed to the same situations as those who do not experience implant failure. Moreover, patients with one implant failure likely suffer from additional failures.[12,13] These phenomena are possibly linked with gene susceptibility. The gene polymorphism has been considered as one of the causes of dental implant failure. Gene polymorphisms may affect gene expression levels and protein production or functions; as a consequence, they influence inflammatory cytokine secretion and regulate inflammatory responses.[14–16] The clinical success of dental implants is based on osseointegration, and any intense inflammatory response can stimulate the resorption of supporting bones and damage this process, leading to implant failure.[15–17]

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which is mainly produced by macrophages, is a potent immune-inflammation mediator that promotes bone resorption by activating osteoclast maturation.[18] The single nucleotide polymorphism at position −308 causes a guanine (G) to adenosine (A) transition in the promoter region of human TNF-α gene.[19] The A allele of this polymorphism significantly enhances TNF-α production, which is associated with several diseases,[20,21] including periodontitis.[22–24] The TNF-α cytokine on peri-implant tissues is highly expressed among patients who suffer from implant loss.[25–27]

TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism associated with the susceptibility to dental peri-implant disease has been explored. However, results remain controversial. Thus, we performed this meta-analysis to summarize previous results and to present a comprehensive and systematic conclusion.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Search strategy

We performed a systematic literature search in PubMed, Embase, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure until July 2015. Our search strategy involved the combination of the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and text words: (dental implant OR oral implant OR peri-implantitis OR implant loss OR implant failure OR implant bone loss) AND (TNF-α OR tumor necrosis factor-alpha) AND (polymorphism OR variant OR mutation OR genetic susceptibility). The reference lists of relevant papers were also manually searched to acquire additional eligible original articles and to supplement the yield of initial search in the databases. Searching tasks were independently performed by 2 researchers.

2.2. Selection criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they satisfied the following criteria: using a case–control or cohort study design; evaluating the association between TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and susceptibility to dental peri-implant disease (categorized into peri-implantitis, implant loss, implant failure, and marginal bone loss) in human; controls defined as subjects with one or more functionally healthy implant(s) for a period of no less than 6 months; and providing explicit genotypes and allele frequencies in each group or presenting sufficient information for odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculation. For studies with overlapping information, the most recently published study with the largest sample size was selected. Letters and reviews were excluded.

Two reviewers independently selected relevant studies. After eliminating distinctly irrelevant reports by screening the titles of all searched publications, the reviewers further read the abstracts and then assessed the full texts.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

The following characteristics of each original study were extracted: including the name of the first author, year of publication, country of origin, ethnicity of the study subjects, disease type, sample size and genotype distributions in case and control groups, age and sex distributions in the 2 groups, smoking status, follow-up duration, and P value for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the control group. In case of a disagreement over abstracted data, a discussion was held between the 2 reviewers. If consensus was not achieved through this approach, a third experienced reviewer was consulted. The deviation of genotype frequencies from HWE among the controls was estimated via Pearson χ2 test. P > 0.05 was considered equilibrium and fine representativeness.

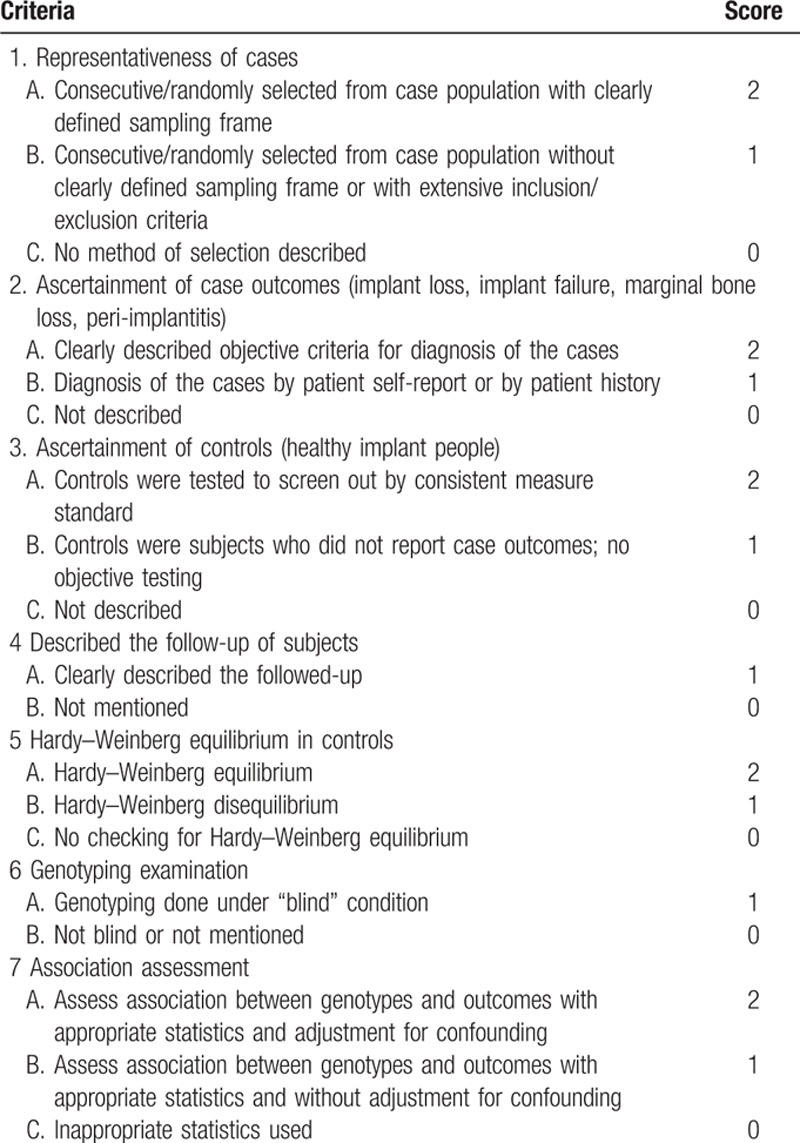

The quality of the included studies was independently evaluated by the 2 reviewers using a modified Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS; Table 1). The maximum score of this NOS is 12, and this scale consists of 7 aspects, namely, case representativeness, selection criteria for both cases and controls, HWE in the control group, follow-up description, blinded examination, and adjustment for confounding factors.

Table 1.

Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for the quality assessment of the included studies.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Odds ratios and corresponding 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate the association between TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and dental peri-implant disease risk in the following genetic models: A versus G; AA versus GG; GA versus GG; GA+AA versus GG; and AA versus GA+GG. Heterogeneity among the included studies was examined on the basis of Cochran Q and I2 statistics. P > 0.1 and I2 < 50% indicated the absence of significant heterogeneity among studies, and a fixed-effect model was used to calculate ORs; otherwise, a random-effect model was utilized.[28] Subgroup analyses were performed on the basis of different characteristics, such as ethnicity and disease type, of the participants. Sensitivity analysis was not performed in this meta-analysis because of the limited number of the included studies. Publication bias was evaluated by using a funnel plot; Egger linear regression test was also conducted when the number of the included studies was >9.[29] Analyses were carried out in Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

Ethical approval and patient consent were unnecessary for this meta-analysis because this study involved a secondary analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study identification

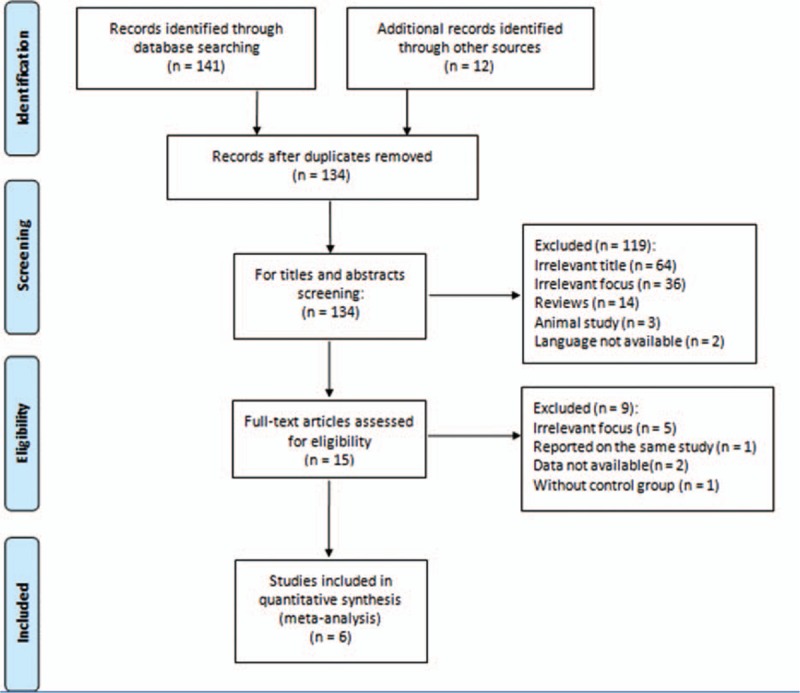

Our literature search initially yielded 153 studies. Of these studies, 19 duplicates were removed. After titles and abstracts were screened, 119 articles were excluded because irrelevant topic was discussed (64), TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism or dental peri-implant disease was not the main topic (36), reviews were presented (14), animals were used as subjects (3), and languages other than English and Chinese were adopted (2). After the full texts were read, 8 publications were eliminated from the present meta-analysis. Of the 7 remaining articles, 2 were reported by the same researcher (Cury, PR) focusing on the same topic. Of these 2 studies, one with a large sample size was published in 2009[30] and the other was reported in 2007.[31] Therefore, we selected the study recently published in 2009. As a result, 6 reports[26,30,32–35] were finally included in this meta-analysis. The flowchart of the selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

3.2. Study characteristics and quality assessment

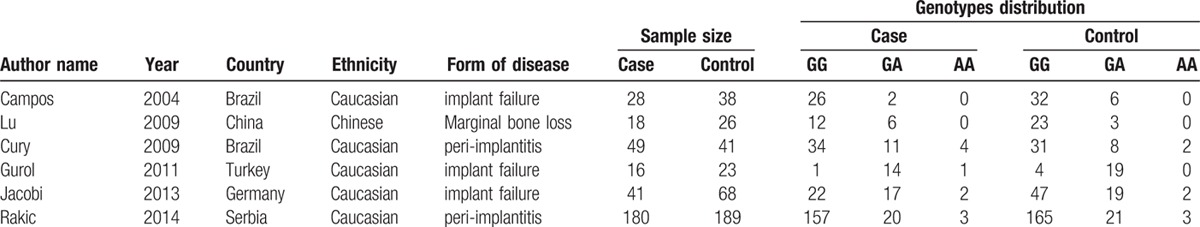

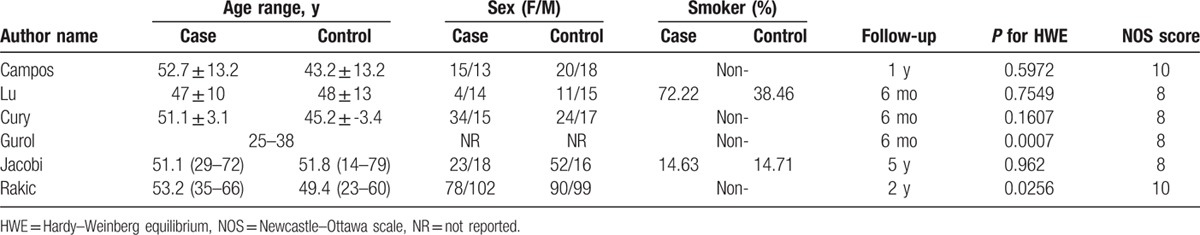

The main characteristics of the 6 included studies are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The earliest study was published in 2004 by Campos,[34] and the latest study was reported in 2015 by Rakic.[33] One study[35] was published in Chinese and the five other studies were presented in English. A total of 717 hospital-based participants were involved in this analysis, and most of them were Caucasians. The subjects aged from 14 to 79 years, and the follow-up duration for functional implants was from 6 months to 5.2 years. Two studies[26,33] obtained positive results, and the 4 other studies[30,32,34–35] yielded negative results. The genotype distribution of the control group deviated from HWE (P < 0.05) in 2 studies.[32–33] The score of the quality assessment for the included studies ranged from 8 to 10 with an average value of 8.7.

Table 2.

Main characteristics extracted from the included studies.

Table 3.

Main characteristics extracted from the included studies.

3.3. Meta-analysis

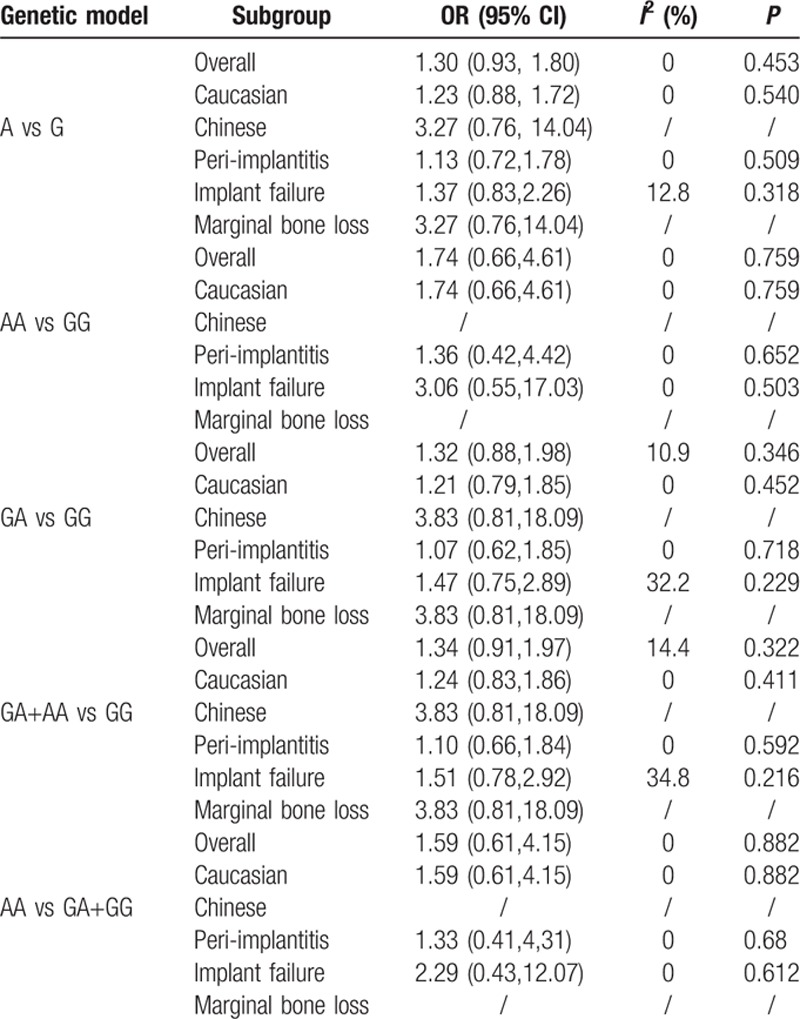

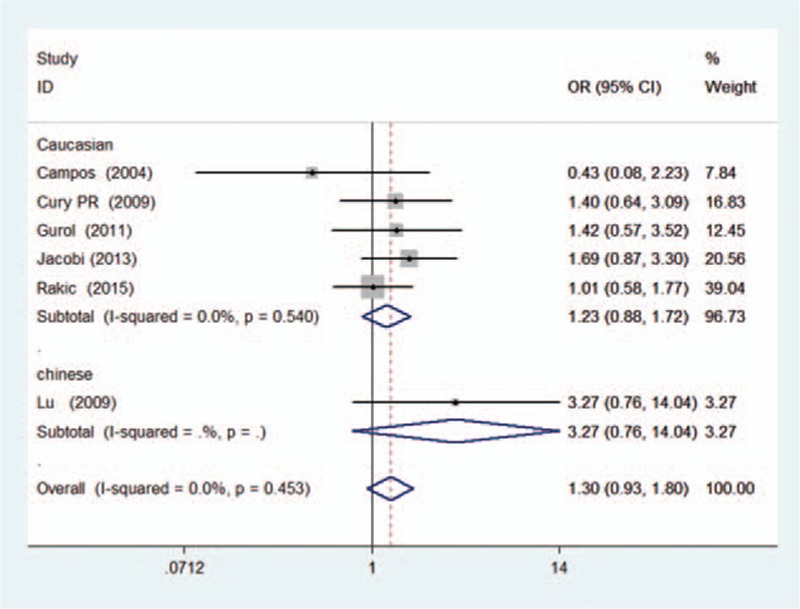

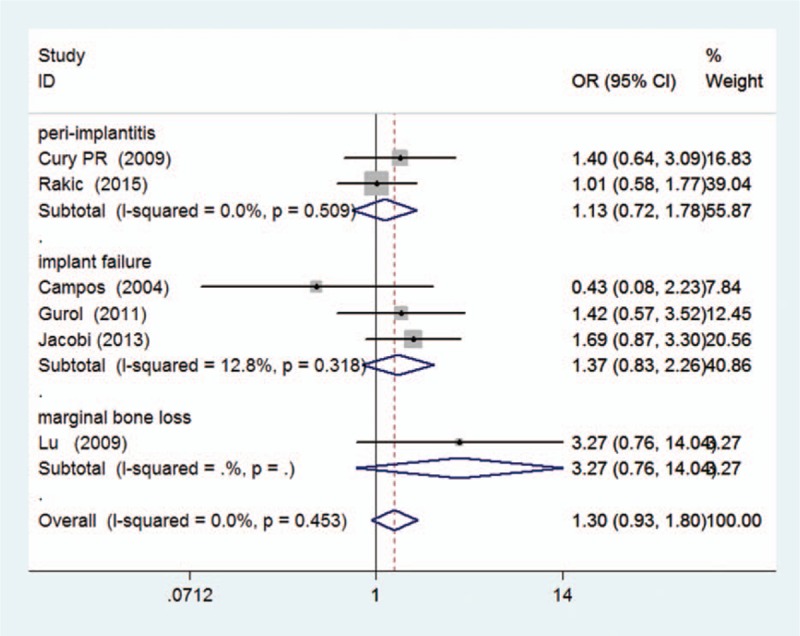

The heterogeneity among the included studies was moderate in each genetic model (P > 0.1 and I2 < 40%, presented in Table 4). Thus, the fixed-effect model was applied to calculate the pooled ORs in this meta-analysis. Consequently, the pooled ORs and 95% CIs in the 5 genetic models did not reveal a significant association between the TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and the dental peri-implant disease risk: (A vs G: OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 0.93–1.80, I2 = 0.0% [Figs. 2 and 3]; AA vs GG: OR = 1.74, 95% CI = 0.66–4.61, I2 = 0.0%; GA vs GG: OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 0.88–1.98, I2 = 10.9%; GA+AA vs GG: OR = 1.34, 95% CI = 0.91–1.97, I2 = 14.4%; AA vs GA+GG: OR = 1.59, 95% CI = 0.61–4.15, I2 = 0.0%). For the subgroup analyses in terms of ethnicity and disease type, a similar result was observed. All of the results related to data analyses are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in 5 genetic models.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of dental implant disease risk associated with TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism in A versus G genetic model (subgroup analysis in terms of ethnicity).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of dental implant disease risk associated with TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism in A versus G genetic model (subgroup analysis in terms of disease type).

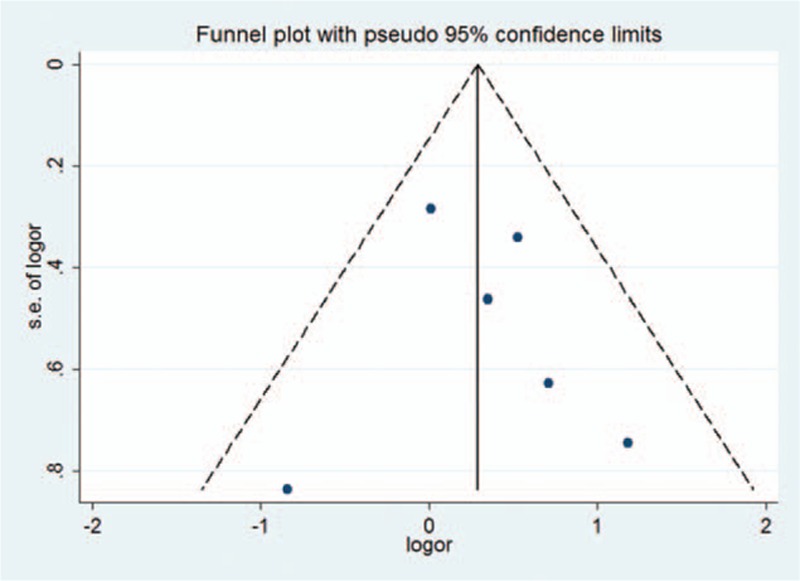

3.4. Publication bias

Publication bias was visually evaluated with a funnel plot (Fig. 4). The shapes of the plots indicated that the included studies did not exhibit significant publication bias.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot for publication bias in A versus G genetic model.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this work is the first to quantitatively assess the association between the TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism and the dental peri-implant disease risk. Despite the relatively small sample size and number of the included studies in this work, this meta-analysis could help summarize relevant findings on the relations of TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism with dental peri-implant disease susceptibility.

In the present meta-analysis, the included studies were case–control ones. The subjects with dental implants were recruited from local hospitals. The subjects were divided into case and control groups on the basis of the outcomes of implants. The control group comprised individuals with healthy implants in functional loading for more than 6 months. The heterogeneity among the included studies was moderate. Thus, the fixed-effect model was used to calculate ORs. Subgroup analyses were also conducted on the basis of ethnicity and disease type. Of the included studies, 5 focused on Caucasian populations, which accounted for 94% of the overall participants, and 1 included Asian populations.[35] The original study conducted by Jacobi[26] observed that the GA or AA genotypes of TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism are more frequent in cases and are associated with an increased risk of implant failure. This finding demonstrates that polymorphism is positively related to disease risk. Rakic[33] concluded that the GA genotype of TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism is positively associated with peri-implantitis; as a consequence, carriers with this genotype are at a fivefold increased risk of peri-implantitis. The 4 other included studies revealed that TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism is not significantly associated with dental implant disease.

Smoking is a high risk factor of dental implant failure.[11] As such, this habit should be considered when individual susceptibility to implant failure is investigated. Of the selected studies, 4 original ones, including 564 subjects (78.6% of all subjects), are non-smokers.[30,32–34] One study[35] reported that approximately 78.6% and 38% of the participants in the case group and the control group are smokers, respectively. Logistic regression analysis was conducted in the original research to adjust for this confounding factor, and the result demonstrated that smoking can increase the risk of early marginal bone loss. In another study,[26] smokers are distributed equally among patients and controls (14.63% in the case group and 14.71% in the control group). Considering the relatively small proportion (5%) of smokers in the total number of participants, we did not conduct a subgroup analysis in terms of smoking status in this meta-analysis.

Patients with periodontitis may also be susceptible to peri-implantitis because periodontitis shares similar clinicopathological features with peri-implantitis.[5,36] As a potential risk factor of dental peri-implant disease, the history of periodontitis is also considered in the majority of included studies. One study[26] has been unable to clearly describe the effect of the history of periodontitis. By contrast, the 5 other studies have definitely stated the elimination of patients who revealed chronic periodontitis history and thus excluded the influence of this confounding factor.

In this meta-analysis, some limitations should be addressed. First, the number of the included studies was relatively small, although we comprehensively searched relevant studies from 5 databases. This small number might influence the statistical power of our meta-analysis results. Our results might be limited in terms of comprehensiveness and thus should be carefully interpreted. Second, the majority of the included studies were based on Caucasians. Therefore, the results may be suitable for this ethnic group but not for other ethnic groups. Further studies should verify whether our results are consistent with other ethnicities. Third, the designs and materials of implants and the experiences of operators were not clarified in the original studies.

We found that TNF-α G-308A polymorphism was not significantly associated with dental peri-implant disease risk in the overall analysis. Similar findings were obtained in the subgroup analyses in terms of ethnicity and disease type. Therefore, TNF-α G-308A polymorphism might not independently affect the susceptibility of patients to dental peri-implant disease.

The negative results in our study might be attributed to the limited sample size. However, the occurrence of peri-implant disease is related to smoking and periodontitis history. The study population was substantially reduced when smokers and periodontitis patients were ruled out.

The lack of consideration of gene–gene interactions may be accounted for our negative results because the inflammatory response of dental implants is regulated by several cytokines. For example, Liao et al[37] performed a meta-analysis on the association between interleukin-1 polymorphisms and dental implant failure. They found that interleukin-1α (−899) and interleukin-1β (+3954) polymorphisms are among the risk factors of dental implant failure/loss and peri-implantitis. Therefore, the combined effects of TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism with other relevant factors on the susceptibility of patients to dental peri-implant disease might not be reflected in our study.

Our negative results should be considered in the investigation of complex processes related to peri-implant disease. Our study can provide systematic suggestions to help clinicians understand this disease. Peri-implant disease is unlikely caused by single gene. This disease can be induced by extracorporeal factors, such as implant materials, surgical operation, and host habits. Considering the complexity of peri-implant disease, researchers should conduct multiple analyses when the risk factors of peri-implant disease are evaluated in further studies.

In conclusion, our findings showed that TNF-α (G-308A) polymorphism was not significantly associated with dental implant disease risk. However, studies on different ethnicities with large sample sizes and gene–gene and gene–environment interactions should be conducted to verify our results.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, HWE = Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium, MeSH = Medical Subject Headings, NOS = Newcastle–Ottawa scale, OR = odds ratio, TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Naert I, Koutsikakis G, Quirynen M, et al. Biologic outcome of implant-supported restorations in the treatment of partial edentulism. Part 2: a longitudinal radiographic study. Clin Oral Implants Res 2002; 13:390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol 2002; 29 suppl 3:197–212.discussion 232-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dereka X, Mardas N, Chin S, et al. A systematic review on the association between genetic predisposition and dental implant biological complications. Clin Oral Implants Res 2012; 23:775–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esposito M, Hirsch J, Lekholm U, et al. Differential diagnosis and treatment strategies for biologic complications and failing oral implants: a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1999; 14:473–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klinge B, Hultin MTB. Peri-implantitis. Dent Clin N Am 2004; 49:661–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esposito M, Hirsch JM, Lekholm U, et al. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants. (II). Etiopathogenesis. Eur J Oral Sci 1998; 106:721–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosshardt DD, Salvi GE, Huynh-Ba G, et al. The role of bone debris in early healing adjacent to hydrophilic and hydrophobic implant surfaces in man. Clin Oral Implants Res 2011; 22:357–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bornstein MM, Cionca N, Mombelli A. Systemic conditions and treatments as risks for implant therapy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009; 24 (Suppl):12–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cosyn J, Vandenbulcke E, Browaeys H, et al. Factors associated with failure of surface-modified implants up to four years of function. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 2012; 14:347–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moy PK, Medina D, Shetty V, et al. Dental implant failure rates and associated risk factors. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2005; 20:569–577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Liu N, Xu X, et al. Smoking, radiotherapy, diabetes and osteoporosis as risk factors for dental implant failure: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8:e71955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alvim-Pereira F, Montes CC, Mira MT, et al. Genetic susceptibility to dental implant failure: a critical review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2008; 23:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deem L, Bassiouny M, Deem T. The sequential failure of osseointegrated submerged implants. Implant Dent 2002; 11:242–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez-Bello J, Vargas-Alarcon G, Tovilla-Zarate C, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): functional implications of regulatory-SNP (rSNP) and structural RNA (srSNPs) in complex diseases. Gac Med Mex 2013; 149:220–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montes C. Analysis of the association of IL1B (C+3954T) and IL1RN (intron 2) polymorphisms with dental implant loss in a Brazilian population. Clin Oral Impl Res 2009; 20:208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu S. No relationship between IL-1B gene polymorphism and gastric acid secretion in younger healthy volunteers. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:6549–6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pigossi SC, Alvim-Pereira F, Alvim-Pereira CC, et al. Association of interleukin 4 gene polymorphisms with dental implant loss. Implant Dent 2014; 23:723–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyce B, Li P, Yao Z. TNF-alpha and pathologic bone resorption. Keio J Med 2005; 54:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson A. Effects of a polymorphism in the human tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter on transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997; 94:3195–3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinhart K, Karzai W. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in sepsis: update on clinical trials and lessons learned. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:121–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalil A, Hall J, Aziz F. Tumour necrosis factor: implications for surgical patients. Aust NZ J Surg 2006; 76:1010–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding C, Ji X, Chen X, et al. TNF-alpha gene promoter polymorphisms contribute to periodontitis susceptibility: evidence from 46 studies. J Clin Periodontol 2014; 41:748–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song GG, Choi SJ, Ji JD, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter -308 A/G, -238 A/G, interleukin-6-174 G/C and -572 G/C polymorphisms and periodontal disease: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2013; 40:5191–5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erciyas K, Pehlivan S, Sever T, et al. Association between TNF-alpha, TGF-beta1, IL-10, IL-6 and IFN-gamma gene polymorphisms and generalized aggressive periodontitis. Clin Invest Med 2010; 33:E85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Recker E. A cross-sectional assessment of biomarker levels around implants versus natural teeth in periodontal maintenance patients. J Periodontol 2015; 86:264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobi-Gresser E, Huesker K, Schutt S. Genetic and immunological markers predict titanium implant failure: a retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 42:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall J, Pehrson NG, Ekestubbe A, et al. A controlled, cross-sectional exploratory study on markers for the plasminogen system and inflammation in crevicular fluid samples from healthy, mucositis and peri-implantitis sites. Eur J Oral Implantol Summer 2015; 8:153–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coory MD. Comment on: Heterogeneity in meta-analysis should be expected and appropriately quantified. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39:932.author reply 933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cury PR, Horewicz VV, Ferrari DS, et al. Evaluation of the effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphism on the risk of peri-implantitis: a case-control study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2009; 24:1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cury PR, Joly JC, Freitas N, et al. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene polymorphism on peri-implant bone loss following prosthetic reconstruction. Implant Dent 2007; 16:80–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurol C, Kazazoglu E, Dabakoglu B, et al. A comparative study of the role of cytokine polymorphisms interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in susceptibility to implant failure and chronic periodontitis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2011; 26:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakic M, Petkovic-Curcin A, Struillou X, et al. CD14 and TNFalpha single nucleotide polymorphisms are candidates for genetic biomarkers of peri-implantitis. Clin Oral Investig 2015; 19:791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campos MI, dos Santos MC, Trevilatto PC, et al. Early failure of dental implants and TNF-alpha (G-308A) gene polymorphism. Implant Dent 2004; 13:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu X. The relationship between TNF-A-308 gene polymorphism and marginal bone loss around dental implants. Guangdong Periodontol 2009; 1006–5245.(01-017-04). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiujie W. History of periodontitis as a risk factor for long-term survival of dental implants: a meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2014; 29:1271–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao J, Li C, Wang Y, et al. Meta-analysis of the association between common interleukin-1 polymorphisms and dental implant failure. Mol Biol Rep 2014; 41:2789–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]