Abstract

Information that details use and supply of respirators in acute care hospitals is vital to prevent disease transmission, assure the safety of health care personnel, and inform national guidelines and regulations.

Objective

To develop measures of respirator use and supply in the acute care hospital setting to aid evaluation of respirator programs, allow benchmarking among hospitals, and serve as a foundation for national surveillance to enhance effective Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) use and management.

Methods

We identified existing regulations and guidelines that govern respirator use and supply at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC). Related routine and emergency hospital practices were documented through an investigation of hospital administrative policies, protocols, and programs. Respirator dependent practices were categorized based on hospital workflow: Prevention (preparation), patient care (response), and infection surveillance (outcomes). Associated data in information systems were extracted and their quality evaluated. Finally, measures representing major factors and components of respirator use and supply were developed.

Results

Various directives affecting multiple stakeholders govern respirator use and supply in hospitals. Forty-seven primary and secondary measures representing factors of respirator use and supply in the acute care hospital setting were derived from existing information systems associated with the implementation of these directives.

Conclusion

Adequate PPE supply and effective use that limit disease transmission and protect health care personnel are dependent on multiple factors associated with routine and emergency hospital practices. We developed forty-seven measures that may serve as the basis for a national PPE surveillance system, beginning with standardized measures of respirator use and supply for collection across different hospital types, sizes, and locations to inform hospitals, government agencies, manufacturers, and distributors. Despite involvement of multiple hospital stakeholders, regulatory guidance prescribes workplace practices that are likely to result in similar workflows across hospitals. Future work will explore the feasibility of implementing the collection and reporting of standardized measures in multiple facilities.

Keywords: Respirator use and supply, Personal Protective Equipment, Hospital settings, PPE Surveillance System

INTRODUCTION

The first line of defense to prevent occupational infections among healthcare personnel (HCP) is personal protective equipment that isolates individuals from pathogens (Siegel et al., 2007; Fischer et al., 2015). Adequate supply and effective use of respirators is necessary to protect HCP from infectious airborne transmissions. A number of related regulations and guidelines for the hospital setting have been established, including the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines that describe when and where respirators should be used and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standard for programs in workplaces where respirators are used (OSHA, 2015). Programs must include respirator selection, training, and fit testing as well as outline workplace practices for both routine and emergency use, provide medical surveillance, and conduct program evaluation (Beckman et al., 2013; Hines et al., 2014; Brosseau et al., 2015).

Evaluation is one of the most commonly omitted requirements in hospital-based respirator programs (Beckman et al., 2013). Evaluation of respirator use and program effectiveness is challenging given the array of factors that influence use of personal protective equipment in health care. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM), five major factors impacting effective use are: (1) the characteristics of disease agents/pathogens, (2) hospital work/task procedures, (3) design of personal protective equipment (PPE) devices or ensembles, (4) knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of HCP and (5) the environmental and organizational context where the respirator is used (IOM, 2010). To increase the effective use of PPEs and to improve technology, the IOM identified a need for more standardization of terms and definitions as well as a comprehensive research strategy that would inform governmental agencies responsible for oversight and manufacturers responsible for design and supply.

Standardized PPE measures and an understanding of their relationships are needed to determine how to establish adequate supply and evaluate effective use. In contrast, measurement of pathogens is advanced in the US given national and state reporting systems, such as the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). As a starting point, the National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) respirator certification program provides a standardized nomenclature for the respirators. Less developed are measures and norms for other factors that - when monitored - can provide insight into effective respirator use and adequate supply, like respirator selection, adequate supply, excess inventory (stockpiles), burn-rates, and HCP knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. A number of questions remain unanswered at this time including:

What is the appropriate number of respirators to stockpile given community rates of isolated patients?

How does training impact effective use of respirators?

Are other measures of infection control practices, such as immunization rates and hand washing frequency indicative of a culture of effective respirator use?

Can uniform measures aid in managing the national supply chain during pandemics or in the event of biological terrorism?

Hospitals vary by type, size, patient population, and location which complicates gathering uniform and timely information to establish adequate supply and effective use. Further, hospitals must overcome dichotomous perspectives among the multiple stakeholders to operate programs effectively (Gerberding, 1993). Different programs and stakeholders are responsible for a multitude of respirator dependent activities, such as clearing personnel for respirator use (Occupational Medicine), assessing implementation of recommended practices to mitigate transmission of airborne infectious diseases (Infection Control and Prevention), overseeing the respirator program mandated by OSHA (Environmental Health and Safety), maintaining a stockpile of respirators (Emergency Preparedness), and managing an appropriate level of respirators (Supply Chain Logistics). Multiple stakeholders - reporting to different hospital departments - make respirator program management and evaluation challenging within the hospital, as well as nationally, especially in the context of tightening resource allocation.

Standardized respirator measures would help answer the outstanding questions identified above and would serve as a foundation to evaluate the effectiveness of use and the adequacy of supply in a timely fashion. Therefore, the objective of our effort was to develop measures at VUMC that would be applicable to all hospitals. We identified common factors of respirator use and supply based on workplace practices of hospital stakeholders charged with implementing various national regulations and guidelines related to prevention of disease transmission and the safety of HCP. We also developed a standardized terminology and data collection tool. This manuscript describes standardizing measures indicative of respirator use and supply, built upon respirator-related regulations and guidelines influencing respirator programming at acute care hospitals and influenced by expert consensus.

METHODS

Environment

The research for this manuscript was conducted at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) in Nashville, Tennessee. VUMC employs 24,176 part-time and full-time faculty and staff and its inpatient facilities consist of three hospitals (adult, children, and psychiatric hospital) (Vanderbilt University, 2015). As of November 2015, VUMC had 978 staffed hospital beds (American Hospital Directory, 2015). Fiscal year 2015 discharges from the three hospitals totaled 59,026, representing 314,288 inpatient days (Vanderbilt University, 2015).

Analysis of Respirator-related Standards, Guidelines, and Advices

We reviewed respirator-related standards, guidance, and advices issued by The Department of Labor, including the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA); the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), including the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH); the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC); the Advisory Committee on Immunization (ACIP); the Institute of Medicine (IOM); the World Health Organization (WHO); the Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs (OWCP); The Joint Commission (TJC); and State of TN Departments of Health and Workforce Development. Documents were identified through interviews with stakeholders, who have responsibility for at least one of the five respirator related activities that impact respirator use as outlined by the IOM (IOM, 2010). All activities and directives related to respirator use in the hospital and the responsible stakeholders at VUMC were documented. Stakeholders provided the directives and instructions received as part of their accountability over respirator related activities.

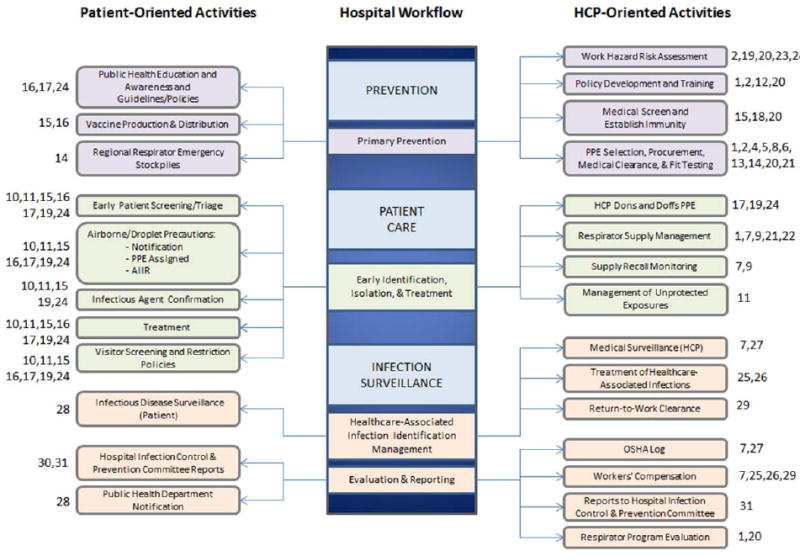

Table I details thirty-one guidelines and regulations affecting hospital airborne pathogen safety programs. The table lists the agency issuing the guidance, the guidance, its intent, and a link to the entire guidance, and the hospital’s role or responsibility. Directives are grouped based on the hospital work they affect: OSHA standards, respirator certification, medical clearance for respirator use, respirator selection, guidelines protecting HCP in general and against specific diseases, pandemic response guidelines, health care personnel injury/illness response, and Joint Commission standards. All activities were grouped according to three major phases of the hospital workflow: prevention, patient care, and infection surveillance (Figure 1). Each governing directive was mapped to specific respirator-related activities. We used this information to create a flowchart of all respirator-related activities occurring during a hospital’s routine and emergency operation. The flowchart further was divided into patient-oriented and HCP-oriented activities to assure that all stakeholder perspectives and activities that may affect respirator use were examined.

Table I.

Table of Guidelines and Regulations Affecting Hospital Airborne Safety Programs

| OSHA Standards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Intent | Responsibilities of Hospital | ||

| 1. | OSHA | Respiratory Protection Standard (29 CFR 1910.134) http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=12716 | To protect the health of employees working in environments requiring the use of a respirator by requiring employers to provide appropriate equipment and training. | To establish and maintain a written respiratory protection program that meets all requirements for respirator selection, storage, training, recordkeeping, and overall program evaluation outlined in this standard. |

| 2. | OSHA | Personal Protective Equipment Standard (29 CFR 1910.132) http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=9777 | To ensure the safety of employees by requiring employers to evaluate workplace hazards and furnish all necessary personal protective equipment (PPE), including equipment for eyes, face, head, extremities such as protective clothing, respiratory devices, and protective shields and barriers. | To complete a written certification verifying that the required workplace hazard assessment has been performed. To provide necessary PPE of all types to employees at no cost, and to train employees to use the PPE appropriately. |

| 3. | OSHA | OSHA General Duty Clause for Employers http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_id=3359&p_table=OSHACT | To maintain healthy and safe workplaces by establishing standards with which all employers must comply. | To furnish a workplace free of hazards likely to cause death or serious harm. To comply with occupational safety and health standards. |

| Respirator Certification | ||||

| 4. | NIOSH | Approval of Respiratory Protective Devices: 42 CFR Part 84 http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/textidx?SID=34d5bb00513ff19a3c73bd2a348d1217&mc=true&node=pt42.1.84&rgn=div5 | In the filing of applications for NIOSH approval of respirators, to establish procedures and requirements, fee schedules, and certificates of approval. Additionally, to specify minimum requirements to be adhered to by the applicant for conducting inspections, examinations, and tests to determine respirator effectiveness. | To supply HCP with NIOSH approved respirators. |

| 5. | NIOSH | The National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory Certified Equipment List http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/CEL/default.html | To test and certify respiratory protective devices, and verify their continued availability to the public. | To provide employees with approved respirator(s) from this list. |

| Respirator Clearing | ||||

| 6. | FDA | FDA’s Role in Regulating PPE http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/GeneralHospitalDevicesandSupplies/PersonalProtectiveEquipment/ucm056084.htm | To oversee the safety and effectiveness of medical devices, including certain PPEs that are subject to regulation under the device provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. | For PPEs that are considered medical devices, and subject to regulation under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, hospitals must purchase and provide FDA-cleared PPEs. |

| 7. | FDA | Overview of Medical Device Regulation http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/default.htm | To regulate firms who manufacture, repackage, relabel, and/or import medical devices sold in the United States. | Under the Medical Device Reporting program hospitals must report incidents and or certain malfunctions of a device that may have caused or contributed to a death or serious injury. |

| Respirator Selection | ||||

| 8. | NIOSH | NIOSH Respirator Selection Logic 2004 http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2005-100/pdfs/2005-100.pdf | To provide respirator program administrators with guidance on respirator selection for their employees. | To answer the questions outlined in the Respirator Selection Logic Sequence to determine the class of respirators that will provide the minimum acceptable degree of protection for specific workplace conditions. |

| 9. | NIOSH | NIOSH Respirator Trusted Source Page http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/topics/respirators/disp_part/RespSource.html | To provide a trusted resource for respirator related questions, including listings of approved respirators, revoked approvals, relevant user notices, and frequently asked questions. | To stay informed about respirator policies and to seek trusted information from NIOSH regarding appropriate types of respirators, implementation of the use of respirators in the workplace, and appropriate use. |

| General Guidelines Protecting Healthcare Personnel | ||||

| 10. | HICPAC | 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/2007IP/2007isolationPrecautions.html | To provide guidelines to healthcare providers for administering infection control programs in the healthcare setting with the objective of reducing the rates of HAIs (Healthcare-Associated Infections) | To commit to improving healthcare delivery and reducing the rates of HAIs by following the HICPAC recommendations and guidelines for infection control programs. |

| 11. | HICPAC | Guideline for Infection Control in Healthcare Personnel http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/InfectControl98.pdf | To recommend preventive strategies for occupational infections including immunizations, isolation precautions, management of HCP exposures. | To follow recommended preventive strategies with the goal of reducing occupational infections in the hospital. |

| 12. | CDC | Workplace Safety & Health Topics: Respirators http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/respirators/ | To compile respirator use resources from the CDC, NIOSH, and OSHA. | To seek guidance from trusted resources when developing and implementing a respiratory protection program. |

| 13. | OSHA | Respiratory Protection for Healthcare Workers Training Video http://www.dol.gov/dol/media/webcast/20110112-respirators/ | To educate end users about the protection provided by respirator use as well as the responsibilities of employers related to respirator use. | To adequately train healthcare personnel to use the respirators provided for them. This video may be part of the training; however, additional worksite specific training is required. |

| 14. | NIOSH | Guidance on Emergency Responder Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Response to CBRN Terrorism Incidents http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2008-132 | To provide emergency responders guidance for PPE use to protect against CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear) terrorism incidents. | To select and provide the proper PPE for emergency responders based on the hazards anticipated to be present, and the probable impact of those hazards. |

| 15. | ACIP | The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - Summary Report February 20-21, 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/min-archive/minfeb13.pdf | To reduce incidence of vaccine preventable diseases and to improve the safety of vaccine administration and immunization techniques. | To consider general immunization guidelines when vaccinating HCP and the general public. |

| Guidelines for Protecting Healthcare Personnel Against Specific Diseases | ||||

| 16. | CDC | Prevention Strategies for Seasonal Influenza in Healthcare Settings http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/healthcaresettings.htm | To recommend a multi-faceted approach to preventing the spread of influenza in healthcare settings among patients, HCP, and visitors. | To implement the influenza prevention measures outlined in this guidance and to implement further supplemental measures during outbreaks. |

| 17. | CDC | Interim Guidance for the Use of Masks to Control Influenza Transmission http://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/maskguidance.htm | To provide interim guidance in response to questions regarding the use of masks to control the spread of influenza with suboptimal immunization of the public. | Prior to ruling out all infectious agents requiring isolation precautions, to offer masks to symptomatic or infected patients and to require HCP to wear masks, who are in close contact with symptomatic patients. |

| 18. | CDC | Recommendation s of the HICPAC and the ACIP – Immunization of Health-Care Personnel http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6007a1.htm | To provide summary recommendations concerning influenza vaccination of HCP. | To maximize HCP influenza vaccination rates, by following these recommendations and by adhering to the evidencebased approaches outlined in this guideline. |

| 19. | CDC | Guidelines for Preventing the Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Health-Care Settings, 2005. MMWR 2005: 54(No. RR- 17, 1-141) http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5417.pdf | To avert a resurgence of TB and eliminate the threat to HCP of contracting TB from undiagnosed patients or other persons, by making updated TB control recommendations. | To implement TB infection control measures while simultaneously safeguarding the confidentiality and civil rights of those who have been infected or who have developed the TB disease including HCP and patients. |

| 20. | NIOSH | TB Respiratory Protection Program in Health Care Facilities – Administrator’s Guide http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/99-143/ | To provide guidance to administrators responsible for implementing the TB respiratory protection program in healthcare facilities. | To establish one individual in charge of the respirator program, who must ensure that the program is written, reviewed, and implemented at the hospital. The program must include a TB risk assessment, process for selecting respirators, written standard operating procedures, manual screening for users, training, fit testing, and program evaluation. |

| Pandemic Response Guidelines | ||||

| 21. | IOM | Preventing Transmission of Pandemic Influenza and Other Viral Respiratory Diseases: Personal Protective Equipment for Healthcare Personnel. Update 2010 http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/Preventing-Transmission-of-Pandemic-Influenza-and-Other-Viral-Respiratory-Diseases.aspx | To assess the progress of PPE research to date, to identify future PPE directions for HCP, and to recommend a fourpronged strategy for effective PPE use in the healthcare setting. | To adhere to the recommendations in this report for effective PPE use in the healthcare setting including deliberate planning and preparation, comprehensive training for all personnel, widespread and convenient availability of PPE, and accountability at all organizational levels. |

| 22. | OSHA | Pandemic Influenza Preparedness and Response Guidance for Healthcare Workers and Healthcare Employers (OSHA Publication 3328) http://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA_pandemic_health.pdf | To aid employers and HCP in the preparation and response to an influenza pandemic. | To provide a safe and healthful workplace for employees during an influenza pandemic by considering the research and recommendations and by collaborating with state and federal partners. |

| 23. | OSHA | Guidance on Preparing Workplaces for an Influenza Pandemic (OSHA 3327-05R 2009) http://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3327pandemic.pdf | To help employers properly plan for an influenza pandemic to lessen the impact of the pandemic on society and on the economy and to protect employees. | To adhere to this planning guidance to identify risk levels in the hospital setting and to implement appropriate control measures including good hygiene, cough etiquette, social distancing, the use of PPE, and staying home from work when ill. Additionally, in the event of a pandemic, to seek up-todate information and guidance relative to the specific virus. |

| 24. | WHO | Infection Control Recommendations for Avian Influenza in Healthcare Facilities. (Global Alert and Response Aide-Memoire, 2008) http://apps.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/guidelines/EPR_AM1_E5.pdf?ua=1 | To provide infection control recommendations, including PPE and hand hygiene advice, for preventing the transmission and spread of avian influenza in health-care facilities. | In the midst of uncertainty surrounding the modes of human-to-human avian influenza transmission, to provide care for patients infected with avian influenza while protecting healthcare personnel, other patients, and visitors from transmission of the infection. |

| Healthcare Personnel Injury/Illness Response | ||||

| 25. | OWCP | Office of Workers’ Compensation Programs (OWCP), U.S. Department of Labor http://www.dol.gov/owcp/ | To oversee disability compensation programs for workers or their dependents who have experienced a workrelated injury or occupational disease. | To provide wage replacement benefits, medical treatment, vocational rehabilitation, and other benefits for workers compensation claims. |

| 26. | OWCP | Workers’ Compensation System Overview http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/314020-overview | To protect employee and employer in the wake of work-related injury or illness report. | To provide medical treatment, rehabilitation, and a percentage of prior earnings to the injured worker. |

| 27. | OSHA | PART 1904 –Recording and Reporting Occupational Injuries and Illnesses https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=9638 | To regulate recordkeeping and reporting by employers covered under the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 for the purpose of developing information regarding the causes and prevention of occupation accidents and illnesses, and for maintaining a program of collection, compilation, and analysis of occupational safety and health statistics. | To maintain a timely log and summary of occupational injuries and illnesses for the facility on a calendar year basis. |

| 28. | CDC | 2013 National Notifiable Infection Conditions List http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/script/conditionlist.aspx?type=0&yr=2013 *See your state’s Department of Health website for state reportable diseases | To collect and publish data reported by the states concerning nationally notifiable diseases. | To report cases of nationally notifiable diseases that occurred or were detected within the facility to the state which then informs the CDC. |

| 29. | States’ DOLs | Frequently Asked Questions – Worker’s Compensation: Case Management http://www.tn.gov/laborwfd/wcfaq.shtml#WCcasemgmt *See your state’s Department of Labor website for state workers’ compensation policies | To resolve any disputes and settle claims between employer and employee. | Hospitals that provide case management services for injured/ill employees must develop and monitor treatment plans, assess whether services are cost effective, ensure that employees are following the medical care plan, and formulate a plan for a return to work with regard for workers’ recovery restrictions or limitations. |

| Joint Commission Standards in the Hospital Setting | ||||

| 30. | TJC | The Joint Commission Facts About Hospital Accreditation http://www.jointcommission.org/hai.aspx | To provide a summary of the infection control standards and survey process for hospitals seeking Joint Commission accreditation. | If all eligibility requirements are met, to apply for Joint Commission accreditation, to comply with unannounced on-site surveys. |

| 31. | TJC | The Joint Commission Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals (CAMH) http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/hap_requirements.aspx | To address the hospital’s performance in key areas, and specify requirements to ensure that patients receive care in a safe manner and in a secure environment. | If the hospital provides services addressed by the Joint Commission’s standard, and has applied for Joint Commission accreditation, to undergo an on-site survey by a Joint Commission survey team in which the hospital’s compliance with the applicable standards is assessed. |

Figure 1.

All respirator-related activities (Numbers refer to Table 1) divided into patient-oriented (left) and HCP-oriented activities (right). Activity categories include prevention (top), patient care (middle), and outcomes in form of infection surveillance and documentation (bottom).

Lastly, workflow specific measures were identified. VUMC stakeholder groups were interviewed to confirm areas of responsibility and to identify information systems that document activities associated with their work. Final measures formats were informed by the manner in which the information system of record was storing the measure of interest to reduce the burden of data collection.

Stakeholder Selection and Interviews

We identified VUMC stakeholder groups, who were responsible for implementing parts of a regulation or guideline representing an IOM component of respirator activity including Environmental Health and Safety, Emergency Preparedness, Occupational Health, Infection Control and Prevention, and Supply Chain Logistics. Stakeholders were contacted by researchers affiliated with the Occupational Health group via email or phone to schedule and conduct in person individual interviews. The purpose of the interviews was to confirm or further define the specific activities conducted by each stakeholder as a result of the standards, guidelines, and advice previously reviewed. Stakeholders also described any information systems used at Vanderbilt to collect respirator-related information and detailed the types of data contained in these systems. Some information systems were used by multiple stakeholders, and others were restricted to one department (stakeholder group).

Development of Standardized Quality Measures

In some cases, standardized measures were stored in hospital information systems, while in others, they were recorded on paper. If there was a lack of standardized measures, surveillance measures related to respirator use and factors influencing its use were developed using information and data from the interviewed stakeholders. The data quality was evaluated prior to recommending surveillance measures using these data elements. Examples of data items included: Choice of first and second respirator for fit test; respirator brand, model, and size; number of specific respirator ordered; date of fit test; airborne pathogen requiring isolation; number of HCP exposed without respirator protection; immunizations provided; etc. Each datum was evaluated for its completeness, validity, acceptance, and representativeness (German et al., 2001).

Completeness

Collecting data items from a structured field in a system form was preferred to extracting the information from free text like a report. Extracting data from an electronic system was preferred over paper. Further, completeness required that the collection of a datum had to be completed on its form (as opposed to being left blank).

The system should have a quality assurance check at the point of collection that forces the completion of the data or an auto-generation of a datum.

Validity

c. The data should be entered by the professional, who performed the activity, rather than by personnel tasked with data entry.

d. The data items are defined in a written data dictionary in the system where they were recorded.

e. Auto-generation or picklists are preferred to populate a data item over free text entry.

Acceptance

a. The data item should be required or desired by external hospital stakeholders as well as governmental stakeholders like the CDC and OSHA.

b. The system must be capable of exporting data electronically, for example into a spreadsheet or report or automatically submit data to an outside system.

c. The data should be collected as part of routine reporting by the responsible hospital department.

Representativeness

f. The system of record should be used to populate all data items. For example, the hospital Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) or the human resource system should provide information on personnel and their job titles and responsibilities. Additionally, the laboratory system should provide laboratory result data.

g. The system of record should account in the data collection for the workflow, e.g. medical clearance is done before respirator fit testing.

h. The individual performing an activity that generates the value for a data item should be identified, along with the location where the activity occurred, and the person who completed the data entry (ideally the person delivering the activity).

The measures related to respirator use and the factors influencing use were finalized after confirming that the data elements required to calculate the recommended measures were quality data elements as indicated by fulfilling the requirements for completeness, validity, acceptance, and representativeness.

Planning for a Surveillance System Structure

The conceptual basis for our surveillance structure is rooted in management theory and practice, and more specifically in control theory. Control Theory originated in the early 19th century in the engineering discipline (Bennett, 1996). By the mid-19th century, the management discipline adopted Control Theory principles and applied them to management processes. One of the most widely used management control models uses three sets of controls: feed-forward, concurrent, and feedback (Barnat, 2015). Feed-forward control ensures that people and materials flowing into the system meet its standards. This approach is a method for preventing problems for example from faulty materials or inexperienced employees. Concurrent control regulates ongoing activities to ensure that they conform to organizational standards. Concurrent controls can involve checkpoints or quality control that can be used to monitor a process and its adherence to standards. Feedback is used to describe outcomes and measure a program’s effectiveness.

Feed-forward metrics can be used in a respiratory protection program to evaluate hospital preparedness with respect to respirator-related activities. Concurrent controls can involve checks and measures to monitor a process and its adherence to standards, and feedback metrics can evaluate outcomes of respirator-related activities such as occupational infections.

RESULTS

Tiered Hospital Workflow of Respirator Related Activities

Figure 1 documents all respirator-related activities at the VUMC hospital, as confirmed by Vanderbilt stakeholder interviews. Activities are divided into patient-oriented (left) and HCP-oriented activities (right). Activity categories include prevention (top), patient care (middle), and outcomes in the form of infection surveillance and documentation (bottom). Understanding the work and its workflow was critical to establishing useful surveillance metrics for respiratory protection programs and other relevant activities.

The activities in Figure 1 also reflect the feed-forward, concurrent, and feedback management control structures. Data in information systems related to preventive activities produced the recommended feed-forward preparedness metrics while data related to patient care activities produced the recommended concurrent responsiveness metrics, and data related to infection surveillance produced the recommended feedback outcome metrics. Interviews confirmed that stakeholders were responsible for tracking activities at all three levels making it feasible to construct surveillance measures using quality data items for all workflow levels.

The specific stakeholder groups that oversee the activities shown in Figure 1 vary among hospitals. For example, at VUMC, the Environmental Health and Safety group is responsible for respirator fit tests and training, while at other hospitals, this duty may fall to Occupational (or Employee) Health. Additionally, routine respirator purchasing may be managed centrally or managed by Emergency Preparedness for the purpose of planning for emergencies. Ultimately, respirator use should be centralized as per guidance outlined in the OSHA 1910.134 Standard.

Multiple federal directives govern hospital workflow, ensuring that rather than being unique to any one hospital, respirator related workflow is similar (but not identical) in all hospitals. Additionally, the mappings of directives to Figure 1 reveal that respirator use and the surrounding oversight permeate all levels of hospital workflow.

VUMC stakeholders responsible for oversight of the respirator-related activities in Figure 1 include Environmental Health and Safety, Occupational (Employee) Health, Infection Control and Prevention, Emergency Preparedness, and Supply Chain Logistics.

Recommended Measures for Infection Prevention Programs in Acute Care Hospitals

Table II displays the recommended measures around respirator use. These recommendations were derived by consensus from the authors. The table displays the primary measures (left column) that are then broken up into a subset of secondary measures (indented). Primary measures should appear on the first page of a hospital’s reporting dashboard, while secondary measures are detailed information that should be provided when a stakeholder requires more information about a primary measure. The right column provides a more detailed description and efforts at disambiguation of the measures to allow a hospital to implement the measure collection. The measures focus on respirator availability, usage, and replacement, availability of trained personnel, number of isolation rooms, hand washing and immunization practices, frequency of isolation orders as a proxy of suspected infection, airborne surveillance programs as well as airborne exposures and hospital acquired infections. Baseline hospital statistics such as staffed beds, patient days, and hospital admissions allow a comparison across institutions of various type, sizes, and locations.

TABLE II.

Recommended Measures for Infection Prevention Programs in Acute Care Hospitals: Respirator Use and Influencing Factors

| PREPAREDNESS | |

|---|---|

| Primary and Secondary Measures | Descriptions |

1. Respirators available to the hospital

|

1. Total number of respirators available to the hospital from all sources on the last day of the reported month

|

2. Number of HCP in the respirator program ready to wear a respirator (N95 or PAPR)

|

2. The total number of HCP in the respirator program who completed their annual N95 fit test/training or PAPR training in the previous year as of the last day of the reporting month.

|

3. Number of airborne Infection Isolation Rooms (AIIRs)

|

3. Number of designated AIIRs in hospital as of report date

|

| RESPONSIVENESS | |

4. Pathogens requiring airborne precautions

|

4. List of infectious airborne pathogens , known or suspected in hospitalized patients, for which airborne precautions are required

|

5. Number of Airborne Isolation Orders

|

5. Number of airborne isolation orders issued during the reported month for suspected or confirmed airborne respiratory pathogens. Note: Patients may be counted more than once.

|

6. Percent of personnel who have experienced problems with respirator

|

6. During the reported month, number of HCP fit tested for a N95 respirator or trained to wear a PAPR, who indicated that they experienced at least one problem when wearing a respirator per number fit tested/trained(2b) Note: Excludes HCP fit tested/trained for the first time.

|

7. Respirators Ordered

|

7. Total respirators ordered during the reported month (N95 and PAPR)

|

8. Airborne Exposure Events in HCP (Unprotected Exposures)

|

8. Number of times an airborne exposure occurred in HCP prior to airborne precaution notification, when at least 1 person did not wear a respirator

|

| OUTCOMES | |

| 9. HCP medical surveillance programs for the early detection of occupational infections | 9. During the reported month, type of airborne pathogens for which there is a medical surveillance programs (e.g. TB) |

10. Airborne occupational infections found through medical surveillance screens of HCP

|

10. Total number of airborne occupational infections found through medical surveillance of HCP during the reported month

|

| INFECTION CONTROL PRACTICES CONFOUNDING DETERMINATION OF RESPIRATOR EFFECTIVENESS | |

| 11. Hand Hygiene | 11. HCP practiced appropriate hand hygiene per HCP working in the hospital during the reported month (Formal monitoring program) |

12. Immunizations Mandatory for HCP

|

12. Types of immunizations required for HCP during the reported month

|

13. (Hospital Statistics and Stakeholder Directory)

|

13. (General organization information related to PPE supply and effective use)

|

Legend:

HCP Health Care Personnel

N95 NIOSH-approved N95 respirator

PAPR Powered Air Purifying Respirator

AIIR Airborne Infection Isolation Room

PPE Personal Protective Equipment

These measures gauge or provide proxy measures of activities that must align for an effective system of respirator use in routine and emergency hospital workflow. VUMC stakeholder feedback confirmed that both the primary and secondary measures would be helpful to decision makers for routine monitoring purposes and in the event of an incident requiring flexible and immediate response management. All measures can be further categorized according to hospital workflow phases: prevention or preparedness, patient care or responsiveness, infection surveillance or outcomes, and infection control practices that can confound effective respirator use (i.e., hand washing).

We selected measures that are representative not just for the supply of respirators on hand but also for the workflow and its effective execution. Respirators programs are part of a hospital system involving multiple tasks superimposed on each other. For example, prevention of disease transmission has two distinct workflows impacting respirator use and program effectiveness: (1) patient assessment and treatment and (2) HCP protection. While measures used in surveillance should reflect the factors e.g. respirator selected, measures representing effective execution of the workflow are required as well, e.g. adequate respirator supply, fit testing of personnel and prompt disease identification/ notification.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of respiratory protection programs is important during routine times as well as during emergent situations. Assurance that programs are functional, properly stocked, and have trained personnel is an ongoing effort and is critically important from a public health perspective. Recent occupational infections by HCP of Ebola have demonstrated the need for stockpiles of protective equipment, as well as individuals trained in its use (Liddell et al., 2015).

To assure the effectiveness of a program, it must be evaluated regularly. Evaluation requires standardized measures of respirator use and supply and of the factors influencing the same. Until now, recommended standardized measures for respirator use and supply in the hospital settings have been lacking. A 2009 study of 16 California hospitals revealed that less than half had formal mechanisms or methods to evaluate respirator programs (Beckman, 2013). A later evaluation of Minnesota and Illinois hospitals demonstrated that only 1 out of 15 Minnesota hospitals’ written Respiratory Protection Programs (RPP) completely addressed program evaluation, and only 2 out of 13 Illinois hospitals met the standard (Brosseau et al., 2015). A similar study of New York State hospitals revealed that less than half of reviewed programs had a plan for evaluating the program’s effectiveness (Hines, 2014).

More and better information is needed to enable hospitals to successfully implement respirator programs, maintain them, and assure that they will work as anticipated in the event they must be applied. Additional information is also needed to aid government agencies develop respirator policy and to project the stockpiling needs. Further, better data will help manufacturers improve their products based on their effectiveness in the field. Only a surveillance system of HCP and PPE could produce this type of information.

The challenges of establishing surveillance initiatives in health care are similar to those of establishing surveillance programs across multiple industries. The complexity derives in part from the existence of “mini-industries” within health care (Hood and Larranaga, 2007). The distributed nature and the multiple stakeholders and their respective programs can form silos, rather than leveraging common objectives to develop shared information systems. In addition, hospital workflow is complex and requires that multiple stakeholders work together to protect personnel from occupational infections and patients from health care associated infections. Hospitals face unique challenges in this regard, because new pathogens can be introduced without warning, and because HCP may have to care for contagious patients before knowledge has been developed as to how the disease is transmitted.

Our proposed measures have some limitations that must be discussed. In absence of the ability to measure primary outcomes, we developed some proxy measures that indirectly speak to the effectiveness of the program such as the airborne exposure events, isolation orders, and unprotected exposure events. The lack of understanding of the relative contribution of respirator use and program effectiveness to prevent disease transmission is a limitation. Identifying causes of system failure given the layers of dependencies affecting the ultimate goal (prevention of occupational infections) is challenging and required proxy measures.

The primary goal of respirator use is disease prevention- the ultimate outcome of effective use. While the absence of occupational infections is an encouraging predictor (but not a guarantee) of effective use, the converse does not necessarily indicate failure given the multiple components of the infection control hierarchy. Adequate surveillance of the supply and factors impacting effective use, determination of which factors are predictive of effective programs, and understanding the interaction of these factors within the hospital workflow, as well as among other components of the infection control hierarchy, are immediate needs. At a minimum such a system would allow management of supply, provide a framework for respirator program evaluation, and allow benchmarking of best practices for implementation and resource allocation. At best, data patterns will emerge over time that indicate what practices provide the greatest likelihood that HCP are afforded the best protection.

The objective of surveillance is to identify areas that may need further investigation, improvement, and reevaluation. The infectious diseases hazard control hierarchy is inclusive of engineering controls, administrative controls, and workplace practices, in addition to personal protective equipment. This approach, inclusive of the monitoring of occupational infections and the hazard control hierarchy, will help to indicate adequate controls in the absence of infection, and may signal components in need of investigation when infections exist.

Restricting this surveillance effort to the hospital setting and to respirators was done because of its relative simplicity and the easiness of duplication. Yet this approach represents a good starting point for a national surveillance initiative. Starting modestly by monitoring this one type of equipment (respirators) and one hazard (airborne infectious pathogens) in one health care setting (acute care hospitals) simplifies the approach. The next step in creating a national occupational surveillance system will be to determine standardized measures that are valuable for collection across various PPE types, hazards, and workplace settings. While standardization presents a challenge, hospital workflows have similar tasks from which we will derive measures of use and supply using the overarching guidelines, even in the presence of varying responsibilities of hospital stakeholder groups.

The establishment of standardized measures will provide the means for hospitals to evaluate respiratory protection programs. This data will also inform future federal and state agency recommendations related to respirator use. Hospital, government, and manufacturing stakeholders alike would benefit from national surveillance of respirator use and the factors influencing use in the hospital setting. Just as recommended measures have been defined for respirator surveillance in the paper, so should recommended measures be defined for other forms of protective equipment, such as gloves, gowns, and face shields.

CONCLUSIONS

Adequate PPE supply and effective use that limit disease transmission and protect HCP are dependent on multiple factors associated with routine and emergency hospital practices. We developed forty-seven measures that may serve as the basis for a national respirator surveillance system with standardized measures of respirator use and supply for collection across different hospital types, sizes, and locations to inform hospitals, government agencies, and manufacturers. Despite involvement of multiple hospital stakeholders, regulatory guidance prescribes workplace practices that are likely to result in similar workflows across hospitals. Future work will explore the feasibility of implementing the collection and reporting of standardized measures in multiple facilities.

Acknowledgments

Vanderbilt University gratefully acknowledges the contract received from the CDC/NIOSH/NPPTL for this research (Contract No. 254-2012-M-52393). The Principal Investigator for this research was Dr. Mary Yarbrough, the Executive Director for Vanderbilt Occupational Health and Wellness. Others contribute to this work included professionals in Environmental Health and Safety, Infection Control and Prevention, Emergency Preparedness, and Supply Chain Logistics.

References

- American Hospital Directory. [Nov 11, 2015]; Available online at https://www.ahd.com/

- Barnat R. [Nov 11, 2015];Strategic Management: Formulation and Implementation. Available online at http://www.strategic-control.24xls.com/en104.

- Bennett S. A brief history of automatic control. Control Systems, IEEE. 1996;16(3):17–25. doi: 10.1109/37.506394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman S, Materna B, Goldmacher S, Zipprich J, D’Alessandro M, Novak D, Harrison R. Evaluation of respiratory protection programs and practices in California hospitals during the 2009-2010 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2013 Nov;41(11):1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.05.006. Epub 2013 Aug 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosseau LM, Conroy LM, Sietsema M, Cline K, Durski K. Evaluation of Minnesota and Illinois hospital respiratory protection programs and health care worker respirator use. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2015;12(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2014.930560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer WA, 2, Weber DJ, Wohl DA. Personal Protective Equipment: Protecting Health Care Providers in an Ebola Outbreak. Clin Ther. 2015 Oct 6; doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.07.007. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerberding JL. Occupational infectious diseases or infectious occupational diseases? Bridging the views on tuberculosis control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993 Dec;14(12):686–8. doi: 10.1086/646670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, Milstein RL, Pertowski CA, Waller MN. Guidelines Working Group Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001 Jul 27;50(RR-13):1–35. quiz CE1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines L, Rees E, Pavelchak N. Respiratory protection policies and practices among the health care workforce exposed to influenza in New York State: evaluating emergency preparedness for the next pandemic. Am J Infect Control. 2014 Mar;42(3):240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.09.013. Epub 2014 Jan 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood J, Larrañaga M. Employee health surveillance in the health care industry. AAOHN J. 2007 Oct;55(10):423–31. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. [Nov 11, 2015];Preventing Transmission of Pandemic Influenza and Other Viral Respiratory Diseases: Personal Protective Equipment for Health care Personnel Update 2010. Available online at https://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2011/Preventing-Transmission-of-Pandemic-Influenza-and-Other-Viral-Respiratory-Diseases.aspx. [PubMed]

- Liddell AM, Davey RT, Jr, Mehta AK, Varkey JB, Kraft CS, Tseggay GK, Badidi O, Faust AC, Brown KV, Suffredini AF, Barrett K, Wolcott MJ, Marconi VC, Lyon GM, 3, Weinstein GL, Weinmeister K, Sutton S, Hazbun M, Albariño CG, Reed Z, Cannon D, Ströher U, Feldman M, Ribner BS, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Uyeki TM. Characteristics and Clinical Management of a Cluster of 3 Patients With Ebola Virus Disease, Including the First Domestically Acquired Cases in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2015 Jul 21;163(2):81–90. doi: 10.7326/M15-0530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSHA Office of Training and Education. [Nov 11, 2015];Major Requirements Of OSHA’s Respiratory Protection Standard 29 CFR 1910.134. Available online at https://www.osha.gov/dte/library/respirators/major_requirements.pdf.

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L. [Nov 11, 2015];Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/isolation2007.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vanderbilt University. [Mar 12, 2016];2015 Financial Report. Available online at https://finance.vanderbilt.edu/report/FY2015-FinancialReport.pdf.