Abstract

The regulator of G protein signaling homolog Crg1 was found to be a key regulator of pheromone-responsive mating in the opportunistic human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. A mutation in the CRG1 gene has greatly increased virulence in the prevalently distributed MATα strains of the fungus. Mouse survival time was shortened by 40%, and the lethal dosage was 100-fold less than that of wild-type strains. In addition, the increased virulence of crg1 mutant strains was dependent on the transcription factor homolog Ste12α but not on the mitogen-activated protein kinase homolog Cpk1. The enhanced mating due to CRG1 mutation, however, was still dependent on Cpk1. Interestingly, crg1 mutants of MATα cells produced dark melanin pigment under normally inhibitory conditions, which may relate to the mechanism for increased virulence.

Cryptococcus neoformans is a ubiquitous soil-borne basidiomycetous fungus that is the leading cause of fungal meningitis in high-risk individuals such as those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, high-dose chemotherapy, or solid organ and bone marrow transplants (27, 31). Haploid strains of this pathogen are either of the MATα or MATa mating types and, of the MATα strains, the var. grubii accounts for >95% of clinical and environmental isolates, with only two MATa isolates being described thus far (33, 36). The MATα mating-type-associated virulence has been attributed to components of the MATα mating-type locus, such as STE20α, whose mutation resulted in attenuation of virulence (38). Mating, haploid differentiation, and the virulence traits of polysaccharide capsule and melanin production are regulated via two major G protein signal transduction pathways (1, 39). Crg1, a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein homolog, was found to have a key role in the pheromone responsive mating of var. grubii MATα and var. gattii strains (17, 33). Thus, the identification of Crg1 has provided a new insight into the role of G protein signaling in the physiology of the fungus.

The first RGS protein, initially identified from the baker's yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, acts as the GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for the Gα subunit Gpa1 by terminating its activation (3, 5, 6, 13, 22). RGS proteins can also directly interfere with the activation of effector molecules (20, 24) or prevent spontaneous receptor-independent G protein signaling (34). RGS and RGS-like proteins are widely distributed throughout eukaryotic organisms and have an impressive array of regulatory functions affecting cellular growth and development (4, 11, 12, 19). The present study reveals a novel role for an RGS protein in a pathogenic microorganism linking enhanced pheromone response to increased virulence. The resulting hypervirulent C. neoformans strain will be of significant importance in studying the mechanism for fungal virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and media.

C. neoformans var. grubii MATα strain H99 and MATa strain KN99 and C. neoformans var. neoformans MATα strain JEC21 and MATa strain JEC20 were previously described (32, 33, 35). KN99 is the tenth backcross progeny of H99 and KN5, a progeny of a cross between a var. grubii subset MATα strain, 8-1, and the MATa 125.91 strain (33). F99 and F99a are Ura− derivatives of H99 and KN99, respectively.

YPD, YNB, 10% V8 juice agar, 5-fluoroorotic acid, and Nigerseed agar were prepared as described previously (37, 39).

Characterization of the CRG1 gene and disruption of the CRG1 gene in a MATa strain.

A 2.9-kb fragment containing the complete CRG1 coding domain was amplified by PCR from the prototype strain H99 and sequenced. Introns were determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), and the complete coding domain was determined by 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends by using a commercial kit (Invitrogen).

A 1.3-kb fragment containing the partial CRG1 gene was initially used to generate a crg1::URA5 gene disruption allele that was, in turn, used to transform the F99 strain by biolistic transformation (33). The same crg1::URA5 allele was also used to create a crg1 mutant strain from the MATa strain F99a. To complement crg1 mutant strains of both mating types, the 2.9-kb fragment containing the wild-type CRG1 gene was inserted in the plasmid pGMC200 containing a nourseothricin resistance marker gene (NATR), and the construct was used to transform the crg1::URA5 mutant strains. Complemented strains were verified by PCR amplification and Southern hybridization analysis. Other strains with the NATR marker were constructed by using a similar approach.

To obtain double-mutant strains, the PKA1 gene encoding Pka1 (AF288613), the PKR1 gene encoding Pkr1 (AF288614), the CPK1 gene encoding Cpk1 (AF414186), and the STE12α gene encoding Ste12α (AF542529) were all disrupted in the crg1::ura5 mutant derivative to obtain crg1 pka1, crg1 pkr1, crg1 cpk1, and crg1 ste12α strains. The crg1::ura5 strains were obtained by plating the crg1::URA5 strain on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium. The derived α crg1::ura5 strain was again transformed with the pka1::URA5, pkr1::URA5, cpk1::URA5, and ste12α::URA5 gene disruption alleles, respectively. Mutant strains were screened by PCR with respective gene-specific primers and CRG1 gene-specific primers.

The STE12a gene was isolated from the strain 125.91 (29) by using primers 5′-TGCGATCAGGCTACAACCTCT and 5′-TAATCACAGTATGCATTGGAT, and the amplified fragment (4.2 kb) was inserted in pGMC200 and used to transform a crg1 ste12α strain. Expression of the STE12a gene was examined by RT-PCR.

Phenotype characterization of crg1 mutant strains.

Pheromone response was represented by formation of conjugation tubes which was induced at 22°C by streaking cells of opposite mating type on filament agar (39). Mating was performed by coculturing a MATα strain with a MATa strain of the same variety (var. grubii, KN99) or a cross variety (var. neoformans, JEC20) on V8 agar containing 0.1 or 1.5% glucose. Plates were incubated at 22 and 37°C.

Melanin was induced by growing cells in the diphenolic compound-rich Nigerseed agar medium. Melanin-producing strains exhibit dark brown pigment, whereas melanin-defective strains appear as white colonies. The whole-cell laccase activity was measured to provide a quantitative assessment of melanin with 2% azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc.) as the substrate by a previously described method (14). Activities were obtained for cells incubated in minimal asparagine medium without glucose for 4 h at 30 and 37°C. One unit of laccase activity was defined as a 0.01 absorbance at 10 min (107 cells).

Capsule was induced by growing cells in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium for 3 days (18) or overnight in liquid Sabouraud medium (45). Cells grown in Sabouraud medium were washed and grown again for 2 days at 30°C in a 10× dilution of the same medium that was buffered with HEPES (pH 7.3) (45). Cells were stained with India ink and observed with an Olympus microscope (BX51) equipped with a digital camera. Images of capsules were printed, and the thicknesses of capsule from 100 cells were measured. A Student t test was performed to compare capsules between the wild-type and crg1 mutant strains.

Murine models of cryptococcosis.

Cryptococcal yeast cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline, and 50 μl of suspension each was used to infect groups of 4- to 6-week-old female mice. For A/JCR mice, groups of 5 and 10 mice were used for each strain. For C57BL/6 mice, groups of five mice were used per strain. For tests with serially diluted fungal cells, groups of four (A/JCR) or three (C57BL/6) mice per strain were used. Mice were first anesthetized by xylazine-ketamine peritoneal injection, and yeast cells were then applied directly into the mouse's nostrils with a pipette (7, 8). Infected mice were monitored twice daily, and those that appeared to be moribund or in pain were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation. Mouse survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method for survival by using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Brain, liver, spleen, and kidney tissues of infected mice were collected, weighed, homogenized with a Dounce glass homogenizer, and plated on YPD medium after serial dilutions from 1:10 to 1:1,000 were made to determine CFU. Recovered fungal cells were also genotyped for strain verification by PCR. For histopathology study, fresh tissues were collected from moribund mice, immersed in buffered neutral formalin, embedded in wax, and stained with the periodic acid-Schiff reagent. Images were obtained with an Olympus microscope (BX51) equipped with a digital camera.

RESULTS

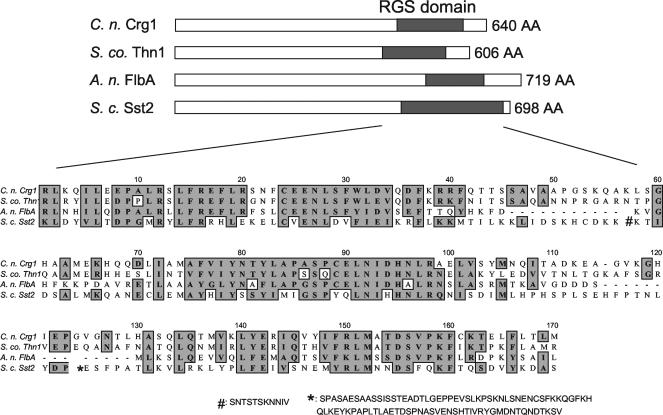

Crg1 is a key regulator of pheromone response in both MATα and MATa strains of var. grubii. The CRG1 gene exists as a single-copy gene in both MATα and MATa strains of C. neoformans var. grubii, and it consists of 1,923 nucleotides encoding a polypeptide of 640 amino acids (GenBank accession no. AY341339). The Crg1 protein shares, respectively, 60, 38, and 24% amino acid identity with Schizophyllum commune Thn1 (AAF78951), Aspergillus nidulans FlbA (AAA35104), and S. cerevisiae Sst2 (S60771) within the RGS domain (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

C. neoformans Crg1 shares a highly conserved RGS domain with other fungal RGS proteins. The amino acid identity within the RGS domain between Crg1 (AY341339) and those of S. commune Thn1 (AAF78951), A. nidulans FlbA (AAA35104), and S. cerevisiae Sst2 (S60771) are 60, 38, and 24%, respectively. The S. cerevisiae Sst2 sequence was truncated, as indicated by “#” and “✽,” for alignment purposes.

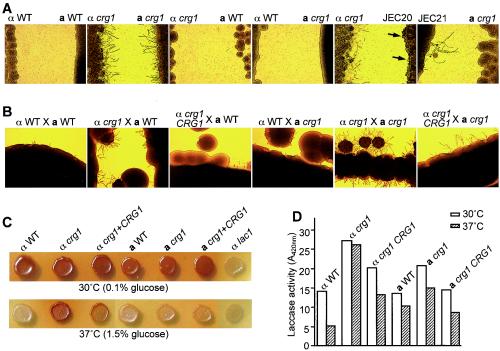

A crg1 mutant strain was generated from the MATa strains F99a (a Ura− derivative of KN99 that is congenic to H99) via biolistic transformation with the same crg1::URA5 allele that was previously used to generate the α crg1 strain (33). In the related var. neoformans for which congenic strains are readily available, MATα cells (strain JEC21) responded to MATa (strain JEC20) pheromones by producing conjugation tubes, a pheromone response, whereas JEC20 produced swollen cells in response to JEC21 pheromones. Whereas the H99 strain did not respond to JEC20 pheromone nor JEC20 to H99, the MATα crg1 strain produced an abundance of conjugation tubes when confronted with JEC20 that also responded by producing swollen cells (Fig. 2A) (33). JEC21 (var. neoformans) produced conjugation tubes when confronted with the MATa crg1 mutant (var. grubii) but not in response to the parental KN99 strain (Fig. 2A). When either a MATα or a MATa crg1 mutant strain was confronted with a compatible wild-type strain of the same var. grubii, conjugation tubes rarely formed (Fig. 2A); however, when both MATα and MATa crg1 mutant strains were confronted, a profusion of conjugation tubes were observed in both mating-type cells (Fig. 2A), demonstrating that Crg1 negatively regulates pheromone response in both α and a cells of var. grubii.

FIG. 2.

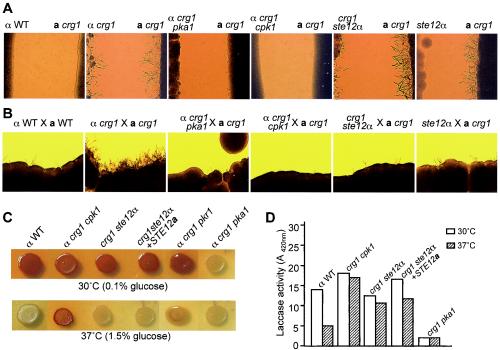

C. neoformans Crg1 is a key regulator of pheromone response in MATα and a strains (A and B) and in melanin formation (C and D). Confrontation tests were performed on filament agar for 3 days at 25°C (A; magnification, ×35). Mating was carried out on V8 agar for 3 days at 25°C (B; magnification, ×14). Cells were grown on Nigerseed agar to induce melanin for 2 days (30°C) (0.1% glucose, panel C, top row) or 3 days (37°C) (1.5% glucose, panel C, bottom row). αWT and aWT are the wild-type strains of var. grubii H99 and KN99, respectively; JEC21 and JEC20 are the wild-type strains of the var. neoformans α and a mating types, respectively. Arrows in panel A indicate swollen cells. The lac1 control strain is defective in melanin biosynthesis in panel C. The data for the laccase activity assay was from one experiment in panel D.

In a qualitative mating assay in which observations were made at an early stage (3 days) after coculture of compatible strains, crosses between crg1 mutant strains (var. grubii) and compatible wild-type strains of either var. grubii or var. neoformans (unilateral) exhibited increased heterokaryotic filamentation, leading to basidia and basidiospore formation (data not shown), and the cross between α crg1 and a crg1 mutant strains (bilateral) exhibited the most robust mating phenotype (Fig. 2B). In addition, both the unilateral and bilateral crosses that involved at least one crg1 mutant strain(s) exhibited the mating phenotype at 37°C on V8 agar supplemented with 1 to 1.5% glucose, conditions normally unfavorable for mating (data not shown). Supplementing the α crg1 mutant strain with the wild-type CRG1 gene reduced the mutant's mating behavior similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2B).

Mutation of CRG1 increases virulence in MATα cells.

The wild-type H99, crg1 mutant, and crg1+CRG1 complemented strains were serially diluted and plated on YPD and YNB media for growth at 30 and 37°C. No apparent difference in colony size was observed among these three strains, suggesting CRG1 mutation did not result in growth defect (data not shown). When grown in diluted Sabouraud, a medium that induces the virulence factor antiphagocytic polysaccharide capsule (25, 26), the average size of 100 crg1 mutant cells was 10.70 μm (±1.54), whereas the average size of 100 wild-type cells was 10.92 μm (±1.32) (P = 0.17). However, the average capsule for the crg1 mutant cell was 2.75 μm (±0.62) thick, which was thicker than that of the wild-type cell (2.25 μm [±0.55]) (P < 0.0001).

Also interestingly, a difference in the production of the antioxidant virulence factor melanin (21, 40, 41) was detected in the α crg1 mutant strain in which melanin production was shown to occur under conditions unfavorable for production in the wild-type strain (Fig. 2C). This result was confirmed by quantification of the laccase production that is required for melanin production. The laccase activity was measured in most of the strains when induced in the minimal asparagine medium at 30°C but was much more prominent in the crg1 mutant strain when it was induced at 37°C (Fig. 2D). Two independent crg1 CRG1 complemented strains exhibited similar intermediate levels of melanin pigment and laccase activity (Fig. 2C and D).

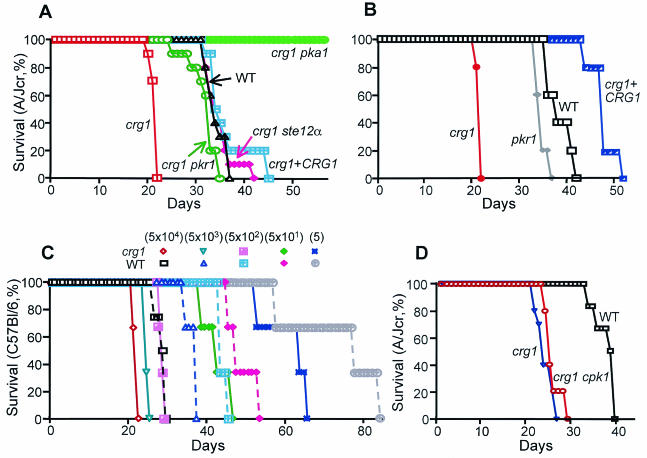

The melanin production by MATα crg1 mutants under the normally inhibitory conditions prompted us to test virulence by using a murine model of cryptococcosis. This model mimicked the natural infection route since fungal cells were placed directly into nasal cavities, promoting inhalation of the organism into the lungs and eventual dissemination to the central nervous system. The wild-type H99 strain produced 100% mortality in A/JCR mice by day 37 when introduced at 5 × 104 yeast cells per mouse (Fig. 3A). In contrast, 100% mortality occurred by day 22 in mice infected with the α crg1 mutant strain (5 × 104 yeast cells per mouse, Fig. 3A and B [P = 0.0001]). Mice infected with the α crg1 mutant complemented with the CRG1 gene exhibited a virulence profile similar to that of H99 (45 days, Fig. 3A [P = 0.299]), indicating that the shortened survival time of the crg1-infected mice was due to the CRG1 mutation.

FIG. 3.

Mutation of the CRG1 gene dramatically increased virulence in MATα cells of C. neoformans. Ten female A/JCR mice per strain (A and D) were infected by nasal inhalation with 50 μl of yeast cells (5 × 104) with the wild-type, crg1, crg1 CRG1, crg1 pka1, crg1 pkr1, and crg1 ste12α strains, and five mice were used in a separate test involving the pkr1 mutant (B). (C) In the test with serial diluted strains, three C57BL/6 mice were used for each strain. Five- to six-week-old mice were used in panels A to C, and 7-week-old mice were used in panel D. Each panel also represents an independent virulence test. Survival was monitored twice daily, and the number of surviving mice was plotted against time. P values were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with Prism 4 software.

To ensure that our findings were not mouse strain specific, the virulence test was repeated in C57BL/6 mice. Again, the increased virulence in MATα cells due to the CRG1 mutation was observed (Fig. 3C and data not shown). To further assess the magnitude of the virulence increase, we inoculated mice with serially diluted H99 and α crg1 mutant cells at concentrations of 5 × 104, 5 × 103, 5 × 102, 50, and 5 cells per mouse (Fig. 3C). In general, survival time correlated with the amount of cells inoculated for each strain. As anticipated by the results in the A/JCR mice, the α crg1 mutant strain was more virulent than the wild-type strain H99. At 5 × 102 yeast cells per mouse, 100% mortality was achieved at day 30 in crg1-infected mice and at day 46 in the wild-type-infected mice (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0295). Survival of mice infected with the crg1 strain at 5 × 102 cells per mouse was the same as that of the mice infected with 5 × 104 wild-type cells (Fig. 3C, P = 0.0753).

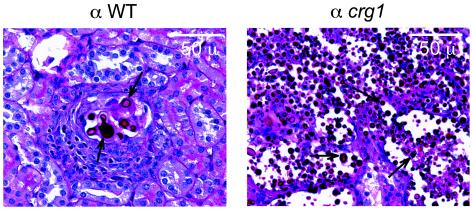

We examined the fungal burden in brains, spleens, livers, and kidneys of moribund mice that were infected, at 5 × 104 cells per mouse, with the wild-type H99 and α crg1 mutant strains. Due to variances of CFU within the same group, possibly caused by a viability difference in yeast cells from freshly sacrificed mice and those that had already deceased, direct comparison was not possible. Nevertheless, fresh kidneys collected from crg1 mutant-infected mice at the lower dose of 50 cells per mouse, which had undergone a longer disease period, did reveal large cryptococcoma lesions packed with yeast throughout the cortical region compared to the kidneys obtained from animals that were infected with the same amount of the wild-type strain that showed only occasional and small lesions in the cortical region with a few cryptococcal yeast cells (Fig. 4). This difference is dramatic; however, whether it relates to hypervirulence remains to be determined since both groups of mice were moribund when the kidneys were collected.

FIG. 4.

Histology study of C. neoformans-infected mouse renal tissue. Three sets of kidneys were collected from moribund mice that were infected, respectively, with 50 cells of wild-type H99 and MATα crg1 mutants. Tissues were fixed in neutral buffered formalin, embedded, sectioned, and stained with the periodic acid-Schiff reagent. Arrows indicate cryptococcal yeast cells.

CRG1 mutation-increased virulence is dependent on the transcription factor homolog Ste12α but not on the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase homolog Cpk1.

Previous studies have shown that at least two G protein signaling pathways function in C. neoformans to regulate mating, filamentation, and virulence (1, 28, 39). The enhanced pheromone response of the crg1 mutant strains implied that Crg1 functions in the mating pathway. Alternatively, the effect of CRG1 mutation on melanin formation could also suggest that Crg1 functions in the Gpa1/cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent signaling pathway since this pathway plays a prominent role in controlling melanin and capsule biosynthesis. To test the genetic interaction between Crg1 and components of these two pathways, crg1 pka1, crg1 pkr1, crg1 cpk1, and crg1 ste12α double-mutant strains were created for epistasis tests.

The crg1 pka1 strain was defective in melanin production and was avirulent, suggesting that cAMP signaling is required for the virulence of crg1 strains (Fig. 3A, wild type versus crg1 pka1, P < 0.0001). Mutation of PKR1 activated the cAMP signaling pathway, resulting in formation of cells with larger capsules that also enhanced virulence (Fig. 3B, wild type versus pkr1, P = 0.0173) (10). Interestingly, mutation of both CRG1 and PKR1 genes did not result in any synergistic effect in virulence because the crg1 pkr1 strain exhibited the virulence profile similar to that of the pkr1 strain (Fig. 3A and B).

The crg1 cpk1 mutant strain was defective in conjugation tube formation and mating (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Crg1 functions upstream of Cpk1 in the MAP kinase mating pathway. Melanin and laccase at 37°C, however, were not affected by CPK1 mutation (Fig. 5), and the crg1 cpk1 strain was also hypervirulent (Fig. 3D, crg1 cpk1 versus wild type, P = 0.0002; crg1 cpk1 versus crg1, P = 0.372). In contrast, mutation of the transcription factor STE12α gene in the crg1 strain did not affect conjugation tube formation and only marginally reduced mating to KN99 (Fig. 5A and B). However, melanin and laccase activity at 37°C were affected by mutation of STE12α (Fig. 5C and D), and the crg1 ste12α strain was not hypervirulent, exhibiting a virulence profile similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A, wild type versus crg1 ste12α, P = 0.846). Previously, mutation of the var. grubii STE12α gene had resulted in only a moderate reduction in mating (with the serotype D MATa tester strain JEC20) but had no impact on virulence (44). Finally, the expression of the allelic STE12a gene in the crg1 ste12α strain resulted in a restoration of robust mating (data not shown), but the crg1 ste12α STE12a reconstituted strain remained nearly unchanged in the formation of melanin and laccase activity (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Crg1 regulates pheromone responsive mating and virulence via distinct pathways. (A and B) The increased pheromone response and mating is dependent on the MAP kinase homolog Cpk1, cAMP signaling, and partially on the transcriptional factor homolog Ste12α. Conditions for confrontation and mating were as described in Fig. 2. (C and D) Melanin formation and the laccase activity of the crg1 strain under the normally inhibitive condition are dependent on the transcription factor Ste12α but not the MAP kinase Cpk1 or Ste12a. Conditions for inducing melanin and measurement of the laccase activity were the same as described in Fig. 2. (D) The crg1 pkr1 strain was not tested.

DISCUSSION

G-protein-mediated signal transduction has evolved to play an important role that allows C. neoformans to sense not only external cues, such as pheromones, but also host-associated changes, such as changes in temperature, alterations in pH and CO2 concentrations, and the hosts' immune defense, and to respond by altering gene expression regulating growth and proliferation. Thus, mutation of CRG1 resulted in enhanced pheromone response and increased virulence in MATα cells are likely caused by appropriate alterations of G-protein-mediated signal transduction events.

Sequence conservation between Crg1 and other fungal RGS family proteins, such as S. cerevisiae Sst2, within the RGS domain suggest Crg1 could have a function in pheromone responsive mating. Indeed, mutation of the CRG1 gene resulted in enhanced pheromone response in both MATα and MATa strains of var. grubii (33) (the present study) and in the distant var. gattii (17). The function of two additional fungal RGS proteins, the S. commune Thn1 and A. nidulans FlbA, in mating is not known, but the corresponding mutant strains both exhibited severe defects in vegetative growth (16, 43). Surprisingly, mutation of the CRG1 gene dramatically increased virulence in the prevalently distributed and clinically important MATα cells. This is in sharp contrast to other signaling components of C. neoformans or other model fungi in which gene deletion often had no impact or only resulted in attenuation or loss of virulence. Nevertheless, “hypervirulent” strains due to mutation of “anti-virulence” genes (15) have been reported recently in the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the protozoan parasite Leishmania major (9, 30). In L. major, mutation of the PTR1 gene encoding pteridine reductase I resulted in a >50-fold increase over the wild-type strain in lesion formation in a murine model (9). In fungi, transformation of Colletotrichum coccodes with the NEP1 gene encoding a phytotoxic protein increased its ability to kill the weed Abutilon by a factor of nine (2). In a clinical isolate of the budding yeast S. cerevisiae, a strain carrying a mutation in the SSD1 gene encoding a 160-kDa cytoplasmic protein thought to alter the cell surface structure exhibited increased virulence in DBA/2 mice due to its ability to overstimulate the proinflammatory response (42). However, both the clinical and the ssd1 mutant yeast strains were avirulent in other mouse strains such as BALB/c (42). Finally, hypervirulence has also been demonstrated in the pathogenic fungus Candida glabrata, in which a mutation of the S. cerevisiae transcription factor Ace2 homolog resulted in host tissue penetration by the pathogen, pathogen escape from the blood vessels, and overstimulation of the host's proinflammatory response in a murine model of invasive candidiasis (23). In C. neoformans, mutation of the PKR1 gene encoding the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A regulatory subunit Pkr1 resulted in cells with large capsules and an increase in virulence (Fig. 3B) (14). Cryptococcal cells with similarly large capsules can also be achieved by mutation of the SCH9 gene encoding a S. cerevisiae Sch9 protein kinase homolog. However, the sch9 mutant strain was attenuated in virulence despite the presence of a large capsule (P. Wang et al., unpublished data). In contrast, mutation of CRG1 has not resulted in a dramatically larger capsule similar to that produced by the pkr1 or sch9 strain. An increase in capsule thickness was detected in the crg1 cells under the capsule inducing conditions compared to the wild-type strain; however, the increase in capsule thickness was not to the extent found in the pkr1 or sch9 strains. Thus, the greater virulence increase due to CRG1 mutation is likely via distinct regulatory circuitry.

The enhanced pheromone response due to the mutation of CRG1 suggests that Crg1 interacts with one of the unreported G protein α subunits and that the deletion of CRG1 resulted in prolonged activation of the Gpb1-protein-mediated mating pathway. Efforts are under way to identify additional Crg1 target proteins. Our study supports a model in which Crg1 functions upstream of the Gpb1/MAP kinase cascade for regulating mating and conjugation tube formation, as well as upstream of the transcription factor Ste12α to promote melanin formation under normally prohibitive conditions and increase virulence. Unlike S. cerevisiae, Ste12α of C. neoformans is less likely to serve as the direct downstream component of the mating pathway and is likely involved in several pathways, including mating and filamentation (10). The key element in CRG1 mutation-associated hypervirulence could be the divergent function of Ste12α/a. Activation of mating due to CRG1 mutation may cause the upregulation of the Ste12α pathway that subsequently promotes melanin formation under stressed conditions, such as at a higher glucose level or higher temperature. Increased melanin may help to promote stress tolerance, benefiting fungal survival, or alter the host immune response, thereby increasing virulence.

In summary, our study for the first time links enhanced mating of MATα cells to increased virulence and created a novel hypervirulent C. neoformans strain that will allow us to further elucidate the mechanisms of fungal virulence.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Alspaugh and J. Heitman for providing strains and discussion; N. Cutler, M. Duverney, and A. Prat for technical assistance; and D. Fox for reviewing the manuscript.

This research was supported in part by a fund from the Children's Hospital in New Orleans, La., and grants from the National Institutes of Health to P.W. (AI054958) and to J.E.C. (AI24912).

REFERENCES

- 1.Alspaugh, J. A., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1997. Cryptococcus neoformans mating and virulence are regulated by the G-protein α subunit Gpa1 and cAMP. Genes Dev. 11:3206-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amsellem, Z., B. A. Cohen, and J. Gressel. 2002. Engineering hypervirulence in a mycoherbicidal fungus for efficient weed control. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1035-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apanovitch, D. M., K. C. Slep, P. B. Sigler, and H. G. Dohlman. 1998. Sst2 is a GTPase-activating protein for Gpa1: purification and characterization of a cognate RGS-Gα protein pair in yeast. Biochemistry 37:4815-4822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman, D. M., and A. G. Gilman. 1998. Mammalian RGS proteins: barbarians at the gate. J. Biol. Chem. 273:1269-1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, R. K., and C. A. Otte. 1982. Isolation and genetic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants supersensitive to G1 arrest by a factor and α factor pheromones. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, R. K., and C. A. Otte. 1982. Physiological characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants supersensitive to G1 arrest by a factor and α factor pheromones. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:21-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox, G. M., H. C. McDade, S. C. A. Chen, S. C. Tucker, M. Gottredsson, L. C. Wright, T. C. Sorrell, S. D. Leidich, A. Casadevall, M. A. Ghannoum, and J. R. Perfect. 2001. Extracellular phospholipase activity is a virulence factor for Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 39:166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, G. M., J. Mukherjee, G. T. Cole, A. Casadevall, and J. R. Perfect. 2000. Urease as a virulence factor in experimental cryptococcosis. Infect. Immun. 68:443-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham, M. L., R. G. Titus, S. J. Turco, and S. M. Beverley. 2001. Regulation of differentiation to the infective stage of the protozoan parasite Leishmania major by tetrahydrobiopterin. Science 292:285-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson, R. C., C. B. Nichols, G. M. Cox, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2003. A MAP kinase cascade composed of cell type specific and nonspecific elements controls mating and differentiation of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 49:469-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vries, L., and M. G. Farquhar. 1999. RGS proteins: more than just GAPs for heterotrimeric G proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 9:138-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vries, L., B. Zheng, T. Fischer, E. Elenko, and M. G. Farquhar. 2000. The regulator of G protein signaling family. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 40:235-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dietzel, C., and J. Kurjan. 1987. Pheromonal regulation and sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SST2 gene: a model for desensitization to pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:4169-4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D'Souza, C. A., J. A. Alspaugh, C. Yue, T. Harashima, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2001. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase controls virulence of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3179-3191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foreman-Wykert, A. K., and J. F. Miller. 2003. Hypervirulence and pathogen fitness. Trends Microbiol. 11:105-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fowler, T. J., and M. F. Mitton. 2000. Scooter, a new active transposon in Schizophyllum commune, has disrupted two genes regulating signal transduction. Genetics 156:1585-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, J. A., R. L. Subaran, C. B. Nichols, and J. Heitman. 2003. Recapitulation of the sexual cycle of the primary fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: implications for an outbreak on Vancouver Island, Canada. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1036-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Granger, D. L., J. R. Perfect, and D. T. Durack. 1985. Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans: regulation of capsule synthesis by carbon dioxide. J. Clin. Investig. 76:508-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hepler, J. R. 1999. Emerging roles for RGS proteins in cell signalling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 20:376-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hepler, J. R., M. D. Berman, A. G. Gilman, and T. Kozasa. 1996. RGS4 and GAIP are GTPase-activating proteins for Gqα and block activation of phospholipase Cβ by γ-thio-GTP-Gqα. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:428-432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobson, E. S., and S. B. Tinnell. 1993. Antioxidant function of fungal melanin. J. Bacteriol. 175:7102-7104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kallal, L., and R. Fishel. 2000. The GTP hydrolysis defect of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant G-protein Gpa1(G50V). Yeast 16:387-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamran, M., A.-M. Calcagno, H. Findon, E. Bignell, M. D. Jones, P. Warn, P. Hopkins, D. W. Denning, G. Butler, T. Rogers, F. A. Muhlschlegel, and K. Haynes. 2004. Inactivation of transcription factor gene ACE2 in the fungal pathogen Candida glabrata results in hypervirulence. Eukaryot. Cell 3:546-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koelle, M. R. 1997. A new family of G-protein regulators: the RGS proteins. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9:143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozel, T. R., and E. C. Gotschlich. 1982. The capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans passively inhibits phagocytosis of the yeast by macrophages. J. Immunol. 129:1675-1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozel, T. R., G. S. Pfrommer, A. S. Guerlain, B. A. Highison, and G. J. Highison. 1988. Role of the capsule in phagocytosis of Cryptococcus neoformans. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10(Suppl. 2):S436-S439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon-Chung, K. J., and J. E. Bennett. 1992. Cryptococcosis, p. 397-446. In Medical mycology. Lea & Febiger, Malvern, Pa.

- 28.Lengeler, K. B., R. C. Davidson, C. D'Souza, T. Harashima, W.-C. Shen, P. Wang, X. Pan, M. Waugh, and J. Heitman. 2000. Signal transduction cascades regulating fungal development and virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:746-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lengeler, K. B., P. Wang, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. Identification of the MATa mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans reveals a serotype A MATa strain thought to have been extinct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14455-14460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manca, C., L. Tsenova, A. Bergtold, S. Feeman, M. Tovey, J. M. Musser, C. E. Barry, V. H. Freedman, and G. Kaplan. 2001. Virulence of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolate in mice is determined by failure to induce Th1 type immunity and is associated with induction of IFN-α/β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5752-5757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell, T. G., and J. R. Perfect. 1995. Cryptococcosis in the era of AIDS: 100 years after the discovery of Cryptococcus neoformans. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8:515-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore, T. D. E., and J. C. Edman. 1993. The α-mating type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans contains a peptide pheromone gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13:1962-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nielsen, K., G. M. Cox, P. Wang, D. L. Toffaletti, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2003. Sexual cycle of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and virulence of congenic a and α isolates. Infect. Immun. 71:4831-4841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siekhaus, D. E., and D. G. Drubin. 2003. Spontaneous receptor-independent heterotrimeric G-protein signalling in an RGS mutant. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toffaletti, D. L., T. H. Rude, S. A. Johnston, D. T. Durack, and J. R. Perfect. 1993. Gene transfer in Cryptococcus neoformans by use of biolistic delivery of DNA. J. Bacteriol. 175:1405-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viviani, M. A., M. C. Esposto, M. Cogliate, M. T. Montagna, and B. L. Wickes. 2001. Isolation of a Cryptococcus neoformans serotype A MATa strain from the Italian environment. Med. Mycol. 39:383-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, P., M. E. Cardenas, G. M. Cox, J. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2001. Two cyclophilin A homologs with shared and distinct functions important for growth and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. EMBO Rep. 2:511-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, P., C. B. Nichols, K. B. Lengeler, M. E. Cardenas, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2002. Mating-type-specific and nonspecific PAK kinases play shared and divergent roles in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 1:257-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, P., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2000. The G-protein β subunit GPB1 is required for mating and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:352-362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang, Y., P. Aisen, and A. Casadevall. 1995. Cryptococcus neoformans melanin and virulence: mechanism of action. Infect. Immun. 63:3131-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, Y., and A. Casadevall. 1994. Susceptibility of melanized and nonmelanized Cryptococcus neoformans to nitrogen- and oxygen-derived oxidants. Infect. Immun. 62:3004-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wheeler, R. T., M. Kupiec, P. Magnelli, C. Abeijon, and G. R. Fink. 2003. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant with increased virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:2766-2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, J.-H., J. Wieser, and T. H. Adams. 1996. The Aspergillus FlbA RGS domain protein antagonizes G protein signaling to block proliferation and allow development. EMBO J. 15:5184-5190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yue, C., L. M. Cavallo, J. A. Alspaugh, P. Wang, G. M. Cox, J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 1999. The STE12α homolog is required for haploid filamentation but largely dispensable for mating and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Genetics 153:1601-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaragoza, O., and A. Casadevall. 2004. Experimental modulation of capsule size in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biol. Proced. Online 6:10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]