Abstract

This study examined parental, peer, and media influences on Taiwanese adolescents’ attitudes towards premarital sex and intent to engage in sexual behaviors. Participants were a convenience sample of 186 adolescents aged 13–15 years recruited from two middle schools in Taiwan. Parental influence was indicated by perceived parental disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex; perceived peer sexual behavior was used to measure peer influence. Media influence was measured by the adolescents’ perception about whether media promote premarital sex. We conducted structural equation modeling to test a hypothesized model. The findings suggested that the perceived sexual behavior of peers had the strongest effect on Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavioral intent, while parental disapproving attitudes and media influence also contributed significantly to adolescents’ sexual attitudes and intent of engaging in sex. School nurses in Taiwan and globally are in an ideal position to coordinate essential resources and implement evidence-based sexually transmitted infections and HIV/AIDS prevention interventions that address issues associated with influences of parents, peers, and media.

Keywords: adolescent health, health promotion, parent, school nursing, sexual health, social media

Risky sexual behavior among youth is of international concern because of its detrimental consequences which influence adolescent health, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), HIV/AIDS, and their associated psychological and social consequences. Prevention of adolescent risky sexual behavior, including delaying the debut of sexual activity, remains the most cost-effective strategy for reducing these unwanted consequences (Berlan & Holland-Hall, 2010). Evidence suggests that an early sexual debut (i.e., having the first sexual intercourse before age 15), is significantly associated with STIs, unplanned pregnancy, and future risky sexual behavior (e.g., Houlihan et al., 2008; Sandfort et al., 2008). Thus, it is important to examine factors associated with sexual behavior in adolescents before they engage in such behavior.

Research suggests that premarital sexual behavior is becoming more acceptable among Taiwanese adolescents (Zuo et al., 2012). According to Taiwan Health Promotion Administration, 13.09% of boys and 14.58% of girls aged 15–17 reported that they had engaged in sexual intercourse. Among Taiwanese sexually active adolescents, 48.2% of the girls and 74.2% of the boys reported never or inconsistent use of condoms during sexual intercourse (Hsieh et al., 2010). These behaviors put these adolescents at significant risk for contracting STIs.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model (1979), suggesting that individuals are influenced by the joint effects of individual, family, and extra-familial level factors, has been applied extensively to understand adolescent sexual behaviors (e.g., Herrick et al., 2013; Torres et al., 2013). As indicated in the model, for adolescents, the immediate environment (e.g., family/parents, peer) interact with the broader social environment (e.g., media) to influence their sexual attitudes and behaviors. Family and parenting factors, such as parent-child closeness, sexual communication, and parental monitoring, have been found to be associated with adolescent sexual attitudes and/or behaviors in the United States (e.g., Barman-Adhikari et al., 2014; Kao & Martyn, 2014) and in Taiwan (Chang et al., 2014; Lou et al., 2010). Parental disapproval of premarital sexual behavior has been shown to be a strong protective factor in preventing adolescents’ sexual behaviors (Kao & Martyn, 2014; Pai et al., 2010).

Peer norms play a critical role in shaping adolescents’ sexual behaviors (Baumgartner et al., 2011). Chiao and Yi (2011) reported that Taiwanese adolescents were more likely to engage in sexual behaviors if they perceived their best friends as being sexually active. Perceived peers’ sexual behavior was also found to be positively related to premarital sexual permissiveness and actual sexual behaviors in Taiwanese youth (Lou et al., 2012). Chang et al. (2014) found that the normalization of sexual behavior in peers and adolescents’ desire to feel accepted by peers were associated with Taiwanese adolescents’ positive attitudes toward premarital sex.

The rapid development of digital media has significantly changed the ways adolescents seek information and communicate. Evidence shows a high prevalence of media use, in particular internet use (82.6%), for accessing sexual information among adolescents and young adults in Taiwan (Lou et al., 2012). While educational content delivered via digital media has shown great potential in promoting adolescents’ healthy behaviors, negative outcomes associated with inadequate and unsupervised media use is well documented. A survey conducted by Chen and colleagues (2013) showed that 71% of 1166 Taiwanese students in grades 10–12 had been exposed to internet pornography. The exposure to internet pornography was associated with a greater acceptance of sexual permissiveness and a greater likelihood of engaging in sexually permissive behavior (Lo & Wei, 2005). Similarly, Lou and colleagues (2012) found that learning about sex from the internet was positively associated with young Taiwanese males’ permissive attitudes about premarital sex. Further, watching pornographic videos and surfing pornographic websites were positively associated with sexual desire (Chang et al., 2014) and behaviors for both young Taiwanese males and females (Cheng et al., 2014; Lo & Wei, 2005; Lou et al., 2012).

Despite the increased trend for Taiwanese adolescents to engage in sexual behavior, limited research has examined how adolescents’ immediate and broader social environment simultaneously influence their sexual attitudes and intended sexual behaviors. This study aimed to examine parental, peer, and media influences on Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and intent of engaging in sexual behavior.

Model description

Based on the ecological approach and empirical evidence summarized above, we hypothesized that parental disapproval of premarital sex (parental influence), perceived number of peers who engage in sexual behavior (peer influence), and media influence have direct effects on adolescents’ unfavorable sexual attitudes and their intent of engaging in sexual behavior. We also hypothesized that adolescents’ unfavorable sexual attitudes have a direct negative effect on their intent of engaging in sexual behavior. Parental, peer, and media influence were hypothesized to also have an indirect influence on adolescents’ intent of engaging in sexual behavior through adolescents’ unfavorable sexual attitudes. Because gender differences exist concerning sexual attitudes, intent of engaging in sexual behaviors, and actual sexual practice (Petersen & Hyde, 2011), we added gender in the hypothesized model to control for its effect.

METHODS

Design and sample

Anonymous surveys are an efficient and cost-effective method of collecting sensitive data. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional, anonymous survey among a convenience sample of 186 Taiwanese adolescents. A student was eligible to participate if s/he (1) was aged 13–15 years old, (2) could read and write Chinese, and (3) returned both parental consents and adolescent assents.

Our sample size of 186 fell within the range of minimum acceptable sizes for analyzing structural equation models with categorical dependent variables (e.g., N > 100; Flora & Curran, 2004).

Measures

We adapted survey items from valid and reliable published instruments (Lindenberg et al., 2002), and used rigorous procedures to translate, back-translate and validate the survey items in Chinese-speaking adolescents to ensure the items were culturally and developmentally appropriate (Chen et al., 2010). To further enhance the validity, two researchers who are native Chinese speakers and specialize in Taiwanese adolescents’ behavioral health, and two Taiwanese adolescents reviewed the measures prior to the administration. The researchers and Taiwanese adolescents who pilot tested the survey agreed that all measures were linguistically and culturally appropriate, so no revisions were made.

Sociodemographic items included age, gender, family composition, and the highest level of parental education achieved. Participants also identified their primary sources (e.g., healthcare provider, media) for obtaining sexual knowledge. If they identified multiple sources, we asked participants to specify primary, secondary and tertiary sources.

The 12-item Sexual Attitudes Scale assessed attitudes towards premarital sex and pregnancy. Ratings range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with a range of possible scores of 4–48. Seven of the 12 items were reverse coded; a higher total score indicated less favorable attitudes towards premarital sex and pregnancy. The internal consistency of this scale was .75 in this sample.

One item assessed adolescents’ intent of engaging in sexual behavior in the next year; ratings range from 1 (definitely would not do it) to 4 (definitely would do it).

Parental influence was assessed by two items (one for each parent) asking the adolescent’s perception about father’s and mother’s attitudes towards premarital sex (i.e., my father/mother disapproves of premarital sex). Ratings for the 2 items range from 0 (never) to 5 (all the time). A higher score suggests a higher level of parental disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex. The correlation between the two items was .90 (p < .001) in our study.

Peer influence was assessed by the adolescents’ perception of the number of peers who engage in sex. The score ranges from 0 (none of my friends) to 4 (all of my friends). Media influence was assessed by the adolescents’ perception about media’s encouraging attitudes towards premarital sex. The score ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time).

Procedures

We first contacted administrators of middle schools in a suburban area in Taiwan to explain the purpose and procedure of the study, and two schools agreed to participate. Once we received approval from the schools and our University, we randomly selected three classes in each school and held information sessions to explain the study purpose, procedures and confidentiality issues to students and distributed information sheets so students could discuss it with parents. Once parental consents and adolescent assents were returned, eligible students were gathered in classrooms on a preselected time that did not interrupt their learning to fill out the anonymous survey. We provided each participant a blank envelope, so they could seal the survey upon completion. Participants were informed that they could skip any questions they wished not to answer and no personal identifiers (e.g., name) would be collected. One bilingual researcher was available in the classrooms for questions. Students received culturally appropriate incentives (notebooks, pencils) to acknowledge their time and effort.

Ethical considerations

We obtained approval from University Institutional Review Board and school administrators and teachers and received parental consents and adolescent assents before conducting the study. Data was collected via an anonymous survey with a pre-assigned code, and was secured in a HIPAA-compliant and encrypted server with multilevel password protection, enterprise-level firewalls, and antivirus barriers.

Data analysis

We examined the data for invalid and inconsistent responses, outliers, normality, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity to assure that statistical assumptions were met. The survey response rate was 100% with valid values. Descriptive statistics were used to describe sample characteristics; t-test, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney, and chi-square analyses were conducted to compare gender differences in key variables. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypothesized model using Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Parental influence was conceptualized as a latent variable measured by single-item indicators of father's and mother's attitudes towards premarital sex. This latent variable was identified by setting its variance to unity and allowing its factor loadings to be freely estimated. All other variables in the model were treated as observed. Fathers’ and mothers’ attitudes towards premarital sex and adolescents' intent of engaging in sexual behavior were treated as ordinal endogenous variables. We used the Mplus WLSMV estimator to obtain parameter estimates, standard errors, test statistics, and global model fit statistics. The WLSMV estimator uses a weighted least squares method with a mean and variance adjustment to obtain robust standard errors and test statistics that perform well for binary and ordinal dependent and mediating variables in SEM (Rhemtulla et al., 2012).

Satisfactory model fit was determined by a nonsignificant model chi-square test. Because the chi-square test assesses exact model-data fit, it can be sensitive to trivial model misspecification. Thus, we evaluated model fit based on the following fit statistics: Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI); the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the weighted root mean square residual (WRMR). Simulation studies have suggested that if any two of the following three conditions are met, the hypothesized model fits the data well: CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06, and WRMR ≤ 1.00 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu, 2002).

Due to the presence of indirect effects, which may be asymmetric, we used the nonparametric bootstrap (bootstrap samples set at 5,000) to obtain confidence intervals for all indirect and total effect estimates (Hox, 2010). For each coefficient, we reported the unstandardized (B) and standardized (β) regression coefficients, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for B, and p-value. For indirect and total effects, no actual p value was reported. Instead, we reported that the effect was significant at p < 0.05 if the 95% CI did not include zero and significant at p < 0.01 if the 99% CI did not include zero from the bootstrap analysis.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics and descriptive information

Our sample included 186 Taiwanese adolescents (mean age 14.15 [SD = 0.89]); about 59% of them were female. Participants identified friends (33.7%), parents (29.9%) and media (17.8%) as the top three mostly used sources of obtaining sexual knowledge. Although only 4% of the participants reported being sexually active, 21% reported that they would probably or definitely engage in sexual practices in the next year. Approximately 25% of the participants perceived that their fathers or mothers had disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex most or all of the time. Twenty-one percent of them reported one or more of their friends engaged in sex, and 51% of the sample said that media promoted premarital sex.

As shown in Table 1, female adolescents were slightly older, perceived higher level of disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex by their fathers and mothers, reported having fewer friends who engaged in sexual activity, had more unfavorable attitudes towards premarital sex, and had lower intentions to engage in sexual behavior in next year than the male adolescents. We did not find significant gender difference in parents’ education and perceived media influence.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Gender Differences of Variables (n = 186)

| Variables | Total (n = 186) |

Male (n = 77) |

Female (n = 109) |

Gender difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% | M(SD)/% |

#t-test/ Wilcoxon-Mann- Whitney test |

chi-square test | |

| Age | 14.15(0.89) | 13.79(0.71) | 14.40(0.91) | 5.12*** | |

| Parent’s highest level of education | |||||

| Percent father completed high school or higher education | 67.30% | 3.74 | |||

| Percent mother completed high school or higher education | 75.90% | 3.91 | |||

| Parental influence | |||||

| Father disapproves premarital sex | 1.80(1.90) | 1.07(1.59) | 2.27(1.95) | 4.27*** | |

| Mother disapproves premarital sex | 1.80(1.89) | 1.06(1.52) | 2.30(1.96) | 4.22*** | |

| Peer influence | |||||

| How many of your friends who are sexually active? | 0.38(0.87) | 0.57(1.11) | 0.24(0.61) | 2.30* | |

| Media influence | |||||

| Movies, television, magazines and other social media (e.g., internet) promote premarital sex | 0.88(1.33) | 1.00(1.42) | 0.80(1.26) | 0.80 | |

|

Adolescent unfavorable sexual attitudes (sum score) |

39.16(4.94) | 37.42(5.28) | 40.38(4.31) | 3.80*** | |

| Adolescent intent to engage in sexual behavior in next year | 1.70(0.97) | 2.20(1.14) | 1.35(0.62) | 5.42*** | |

We used independent t-tests to compare gender differences in interval variables (age and number of friends who are sexually active), and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test to compare gender differences in ordinal variables (father’s and mother’s disapproving attitudes toward sex, media influence, adolescent’s unfavorable sexual attitudes and their intent of engaging in sexual behavior).

p < 0 .05;

p < 0 .01;

p < 0.001

Correlation

Spearman correlations suggested that adolescents’ unfavorable attitudes towards premarital sex were negatively related to their intent of engaging in sexual behavior (rho = − 0.44, p < 0.001), positively related to both parents’ disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex (rho = 0.14, p = 0.056 & rho = 0.20, p = 0.009; respectively), negatively related to the perceived number of peers who engaged in premarital sex (rho = − 0.29, p < 0.001), and negatively related to perceived media influence (rho = − 0.21, p = 0.005).

Adolescents’ intent to engage in sexual behavior was negatively related to both father’s and mother’s disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex (rho = − 0.23, p = 0.002 & rho = − 0.24 p = 0.002 respectively), positively related to the number of peers who engaged in premarital sex (rho = 0.26, p < 0.001), and positively related to perceived media influence (rho = 0.21, p = 0.004).

Compared with male adolescents, females perceived a higher degree of both parents’ disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex (both were rho = 0.32, p < 0.001), reported more unfavorable attitudes towards premarital sex (rho = 0.28, p < 0.001), and had a lower intention to engage to sexual behavior (rho = − 0.40, p < 0.001).

Model Testing

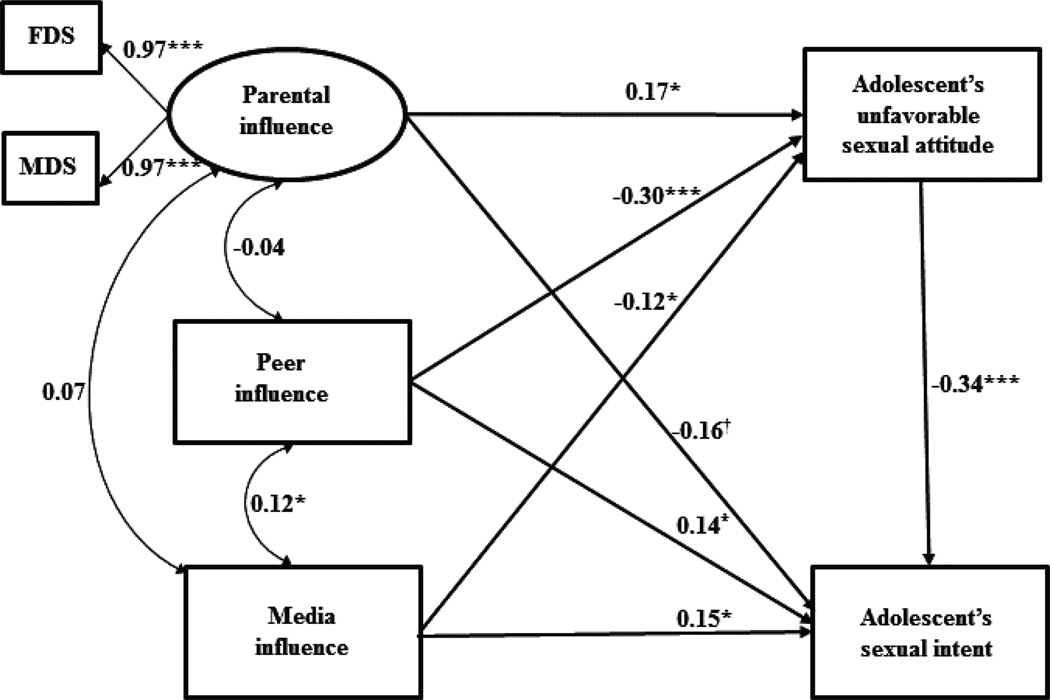

The chi-square test and fit statistics suggested an excellent fit: χ2 (5, N=186) = 3.26, p = .66; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; WRMR = .07. All hypothesized paths in the model were supported by the SEM results (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Final Model of Factors Influencing Taiwanese Adolescents’ Intent of Engaging in Sexual Behavior. Standardized path coefficients are presented. FDS = Father disapproves of premarital sex in the next year; MDS = Mother disapproves of premarital sex behavior in next year; +: positive relationship; - : negative relationship. Gender was included in the model as a control variable. †p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Direct effects

As hypothesized, higher parental disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex (B = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.13, 1.52; β = 0.17; p = .020) was positively associated with adolescents' unfavorable sexual attitudes. Perceiving that more peers were engaging in premarital sex (B = −1.70; 95% CI = −2.34, −1.06; β = −0.30; p < .001), and perceiving that media promoted premarital sex (B = −0.46; 95% CI = −0.82, −0.02; β = −0.12; p = .011), were negatively associated with their unfavorable sexual attitudes.

Adolescents who perceived that media promoted premarital sex (B = 0.11; 95% CI = 0.01, 0.21; β = 0.15; p = .025), and more sexually experienced peers (B = 0.16; 95% CI = 0.01, 0.33; β = 0.14; p = .049) reported a higher intention of engaging in sexual behavior. Parental influence on adolescents’ intention of engaging in sexual behavior was protective as reflected by the negative and marginally significant association between these two variables (B = −0.16; 95% CI = −0.34, 0.02; β = −0.16; p = .072).

Adolescents’ unfavorable sexual attitudes had a negative influence on their intent of engaging in sexual behavior, consistent with our hypothesis (B = −0.07; 95% CI = −0.10, −0.04; β = − 0.34; p < .001).

Indirect effects

The indirect effects from parental influence (B = −0.06; 95% CI = −0.13, −0.01; β = −.06; p < .05), peer influence (B = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.06, 0.21; β = .10; p < .01), and media influence (B = 0.03; 95% CI = 0.002, 0.08; β = .04; p < .05) to adolescents’ intent of engaging in sexual behavior through adolescents’ unfavorable sexual attitudes were all statistically significant in the hypothesized directions.

Total effects

The total effect is the sum of direct and indirect effects. Peer influence had the strongest total effect on adolescents’ intent of engaging in sexual behavior (B = 0.28; 95% CI = 0.09, 0.45; β = 0.24; p < .01), followed by parental influence (B = −0.22; 95% CI = −0.39, −0.03; β = − 0.22; p < .05) and media influence (B = 0.15; 95% CI = 0.02, 0.25; β = 0.19; p < .05).

DISCUSSION

Because adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviors are highly influenced by their parents, peers, and media, we examined a model to understand each of these influences on Taiwanese adolescents’ attitudes toward premarital sex and their intent of engaging in sexual behavior. Our findings indicated that the perceived sexual behavior of peers had the strongest effect on Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavioral intent, while parental disapproving attitudes and media influence also contributed significantly to their sexual attitudes and intent of engaging in sex.

Mounting evidence suggests that parents remain important in nurturing and guiding adolescents to become healthy adults (Kao & Martyn, 2014). In a society that honors filial piety, such as Taiwan, youth are raised and educated to respect, obey, and care for their parents and elders. Thus, parental influence may be greater on Taiwanese adolescents than among adolescents from other cultures. Similar to other research (Chang et al., 2014; Kao & Martyn, 2014; Pai et al., 2010), we found that adolescents’ perception of parental disapproving attitudes towards premarital sex was significantly associated with their unfavorable attitudes and a lower intent of engaging in sexual behavior. These findings highlighted the importance of parental influence on Taiwanese adolescent’s’ sexual attitudes and behavioral intent.

Consistent with prior research (Baumgartner et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2014; Chiao & Yi, 2011; Lou et al., 2012), peers had a profound influence on adolescents’ sexual behaviors. Among the three different sources of influence we examined, perceived peer sexual behavior showed a stronger effect than parental and media influence and therefore suggesting a critical need for establishing positive peer norms in promoting sexual well-being in adolescents. Peer-led HIV/STI prevention interventions have shown promising results in promoting sexual knowledge, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors (e.g., Merakou & Kourea-Kremastinou, 2006; Van der Maas & Otte, 2009). As natural opinion leaders, peers can serve as role models and agents of change to establish and reinforce positive norms to promote healthy behaviors, including delayed sexual debut and protective sexual behaviors. Further, researchers (e.g., Black et al., 2013) have found that adolescents often overreport the perceived sexual behavior of peers relative to their peers’ actual sexual behavior. It is important to clarify adolescents’ misconceptions about their peers’ sexual behavior in health education and prevention interventions.

The rapid development of digital media such as internet, text messaging, social networking (e.g., Facebook) has significantly changed the communication and information-seeking patterns and sources for adolescents in Taiwan. Our finding resembled that of others (Cheng et al., 2014; Lou et al., 2012). The profound impact of media on Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavioral intent can be explained by its private and easy-to-access features, especially in a society where sexual discussion is discouraged (Tung et al., 2014). It may also reflect limited sources for Taiwanese adolescents to access formal sexual education. In fact, our participants identified friends, parents and media as their primary source of sexual information, while only a small percentage of them identified teachers (4%) and healthcare providers (6.3%) as the primary source.

Relying on friends and media as primary sources for sexual information is worrisome, as the information is not evaluated by professionals and can be misleading. Thirty percent of our participants identified parents as the primary source of sexual information is encouraging, as prior research has reported limited parent-child sexual communication in adolescents and young adults (Meechamnan et al., 2014; Tung et al., 2014; Yang &Wu, 2006). However, the content of parent-child communication is unclear. Yang and Wu (2006) reported that parent-child communication is restricted to physical changes, which was not necessarily relevant to their sexual behaviors. Tsai and Wong (2003) indicated that although health education has been included in the middle school curriculum in Taiwan, some teachers may not feel comfortable discussing sensitive, sex-related topic and ask students to study it by themselves. The low proportion of Taiwanese adolescents gaining sexual information from healthcare providers may also reflect that providers have time constraints that prevent them from offering sexual education (Tung et al., 2014). Future research that examines the content of parent-child sexual communication, and strategies that facilitate sexual communication between adolescents and their parents, teachers and healthcare providers is warranted.

Our sample was recruited from a suburban area in Taiwan. Researchers have found that Chinese/Taiwanese adolescents live in urban areas are more likely to be exposed to Internet pornography (Chen & Yang, 2013) and engage in sexual behaviors (Lou et al., 2012) compared to those live in less urbanized areas due to the more conservative culture in less urbanized areas. Future research that compares parental, peer and media influence on adolescents’ sexual attitudes, behavioral intent and actual sexual behaviors across different geographic areas (e.g., urban vs. suburban vs. rural) will provide critical information to inform development of prevention interventions and education appropriate to the local culture.

Limitations

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, it is challenging to identify causal relationships between variables in cross-sectional research. Second, due to the low proportion of sexually experienced adolescents in the sample, we did not examine the model on actual sexual behaviors. Thus, we used a single-item behavioral intent measure as an outcome given its strong association with future sexual behaviors. Future research should consider measuring intent using multiple-item scales to permit assessment of reliability and validity and to gather data on nuances of intentions to engage in different types of sexual behaviors (e.g., oral and anal sex). Similarly, future studies should consider using multiple-item scales to measure parental disapproval of premarital sex, and media and peer influence. Third, we were not able to conduct subgroup analyses by gender due to the relatively small samples in each group. We added gender as a covariate to control for gender effects. Fourth, we did not include other dimensions of parenting, such as parent-child relationship and parental monitoring/supervision, which have been found to reduce adolescents’ involvement with peers who perform high risk behaviors and consequently make adolescents less likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors. Similarly, parental monitoring/supervision of their children’s media use (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2010) and parent-child discussions about the sexual content shown in the media could minimize the media’s potentially harmful effects (Fisher et al., 2009). Future research which examines other aspects of parenting and interactions among parental, peer, and media influences will help us understand the complex relationships of those critical factors on adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviors. Finally, this convenience sample was not representative of Taiwanese adolescents. Thus, the study findings may be generalized to only Taiwanese adolescents aged 13–15 who live in suburban areas. With these limitations in mind, the anonymous nature of this survey should have reduced social desirability and consequently increased validity of the data.

CONCLUSION

School-based HIV/STI prevention interventions are a cost-effective approach to reduce risky sexual behavior in adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). School nurses in Taiwan and globally are in an ideal position to coordinate essential resources and implement evidence-based HIV/STI prevention interventions tailored to middle-school students’ cultural, linguistic, and developmental needs. Nurses in different settings (e.g., family, pediatric, community) also play a critical role in providing education and health care to promote adolescent sexual health. Interventions that help clarify misconceptions about peers' sexual behaviors and reinforce positive peer norms may promote sexual health in adolescents. The significant media influence on Taiwanese adolescents' sexual attitudes and behavioral intent also warrants attention as increasing numbers of children grow up with technology and have access to media. While many parents may believe that their influence over their children would gradually diminish in this developmental stage, the strong influence of parental disapproving attitudes shown in our study is encouraging. Interventions that help parents clarify their roles and influence over their adolescent children; assist them to express their attitudes toward premarital sex via effective communication skills; and set reasonable and consistent family rules, including peer selection and media access, have a high potential to promote Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual well-being.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for sharing their experiences, and school administrators and teachers for their full support and assistance with data collection. Dr. Neilands’s and Dr. Lightfoot’s time was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R25 DA028567) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R25 HD045810). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: ACCC

Data Collection and Analysis: ACCC, TBN, SMC

Manusript Writing: ACCC, TBN, SMC,ML

Contributor Information

Angela Chia-Chen Chen, Arizona State University, College of Nursing & Health Innovation, 500 N 3rd Street, Phoenix, AZ, 85004, United States, angela.ccchen@asu.edu, Phone: +16024960832.

Torsten B. Neilands, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco, Department of Medicine, Division of Prevention Sciences, 550 16th Street, 3F, San Francisco, CA, 94158, United States.

Shu-Min Chan, Shu Zen College of Medicine and Management, No.452, Huanqic Rd. Luzhu Dist., Kaohsiung City 82144 Taiwan (R.O.C.), Tel: 07-6979317, Fax: 07-6073090, pamiechan2014@gmail.com.

Marguerita Lightfoot, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco, Department of Medicine, Division of Prevention Sciences, 550 16th Street, 3F, San Francisco, CA, 94158, United States.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Communications and Media. Policy statement: sexuality, contraception, and the media. Pediatrics. 2010;126:576–582. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman-Adhikari A, Cederbaum J, Sathoff C, Toro R. Direct and indirect effects of maternal and peer influences on sexual intention among urban African American and Hispanic females. Child. Adolesc. Social Work J. 2014;31:559–575. doi: 10.1007/s10560-014-0338-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner SM, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. The influence of descriptive and injunctive peer norms on adolescents’ risky sexual online behavior. Cyberpsycho. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011;14:753–758. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlan ED, Holland-Hal C. Sexually transmitted infections in adolescents: advances in epidemiology, screening, and diagnosis. Adolesc. Med. State. Art. Rev. 2010;21:332–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SR, Schmiege S, Bull S. Actual versus perceived peer sexual risk behavior in online youth social networks. Transl. Behav. Med. 2013;3:312–319. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Bringing High-Quality HIV and STD Prevention to Youth in Schools: CDC’s Division of Adolescent and School Health 2010. [Cited 26 Jan 2016]; Available from URL: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/about/pdf/hivstd_prevention.pdf.

- Chang YT, Hayter M, Lin ML. Chinese adolescents' attitudes toward sexual relationships and premarital sex: implications for promoting sexual health. J. Sch. Nurs. 2014;30:420–429. doi: 10.1177/1059840514520996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AS, Leung M, Chen CH, Yang SC. Exposure to internet pornography among Taiwanese adolescents. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2013;41:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chen ACC, Morrison-Beedy D, Han C-S. Assessing linguistic and cultural equivalency of two Chinese-version sexual instruments among Chinese immigrant youth. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010;25:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Ma J, Missari S. The effects of internet use on adolescents’ first romantic and sexual relationships in Taiwan. Int. Sociol. 2014;29:324–347. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao C, Yi CC. Adolescent premarital sex and health outcomes among Taiwanese youth: perception of best friends’ sexual behaviors and contextual effect. AIDS Care. 2011;23:1083–1092. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.555737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Hill DL, Grube JW, Bersamin MM, Walker S, Gruber E. Televised sexual content and parental mediation: influences on adolescent sexuality. Media Psychol. 2009;12:121–147. doi: 10.1080/15213260902849901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Administration, Ministry Health and Welfare. Survey of healthy behaviors in Taiwanese adolescents 2013. [Cited 26 Jan 2016]; Available from URL: https://olap.hpa.gov.tw/search/ListHealth1.aspx?menu=1&mode=15&year=102.

- Herrick A, Kuhns L, Kinsky S, Johnson A, Garofalo R. Demographic, psychosocial, and contextual factors associated with sexual risk behaviors among young sexual minority women. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2013;19:345–355. doi: 10.1177/1078390313511328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan AE, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Yeh HC, Reimer RA, Murry VM. Sex and the self: the impact of early sexual onset on the self-concept and subsequent risky behavior of African-American adolescents. Early. Adolesc. 2008;28:70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications (2nd edn) New York, NJ: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YH, Shih TY, Lin HW, et al. High-risk sexual behaviours and genital chlamydial infections in high school students in Southern Taiwan. Int. J. STD AIDS. 2010;21:253–259. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kao TSA, Martyn KK. Comparing white and Asian American adolescents’ perceived parental expectations and their sexual behaviors. Sage Open. 2014;4:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg CS, Solorzano RM, Bear D, Strickland O, Galvis C, Pittman K. Reducing substance use and risky sexual behavior among young, low-income, Mexican-American women: Comparison of two interventions. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2002;15:137–148. doi: 10.1053/apnr.2002.34141. (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo V, Wei R. Exposure to internet pornography and Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. J. B. E. M. 2005;49:221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lou C, Cheng Y, Gao E, Zuo X, Emerson MR, Zabin LS. Media's contribution to sexual knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors for adolescents and young adults in three Asian cities. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;50:S26–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou JH, Chen SH, Li RH, Yu HY. Relationships among sexual self-concept, sexual risk cognition and sexual communication in adolescents: a structural equation model. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010;20:1696–1704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meechamnan C, Fongkaew W, Chotibang J, McGrath BB. Do Thai parents discuss sex and AIDS with young adolescents? A qualitative study. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16:97–102. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merakou K, Kourea-Kremastinou J. Peer education in HIV prevention: an evaluation in schools. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2006;16:128–132. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide (7th edn) CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pai HC, Lee S, Chang T. Sexual self-concept and intended sexual behavior of young adolescent Taiwanese girls. Nurs. Res. 2010;59:433–440. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181fa4d48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: a review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. J. Sex. Res. 2011;48:149–165. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.551851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychol. Methods. 2012;17:354–373. doi: 10.1037/a0029315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort GM, Orr M, Hirsch JS, Santelli J. Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: results from a national US study. Am. J. Pub. Health. 2008;98:155–161. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres H, Delonga K, Lee S, et al. Socio-contextual factors: moving beyond individual determinants of sexual risk behavior among gay and bisexual adolescent males. J. LGBT. Youth. 2013;10:173–185. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2013.799000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai YF, Wong TKS. Strategies for resolving aboriginal adolescent pregnancy in eastern Taiwanese. J. Adv. Nurs. 2003;41:351–357. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung WC, Cook DM, Lu M, Ding K. A comparison of HIV knowledge, attitudes, and sources of STI information between female and male college students in Taiwan. Health Care Women Int. 2014;0:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2014.962136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Maas F, Otte WM. Evaluation of HIV/AIDS secondary school peer education in rural Nigeria. Health Educ. Res. 2009;24:547–557. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HH, Wu CI. Adolescents’ communication with parents on sexual topics: a case study of young people in Taiwan. Psychol. Rep. 2006;98:79–84. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.1.79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CY. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Los Angeles; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo X, Lou C, Gao E, Cheng Y, Niu H, Zabin LS. Gender differences in adolescent premarital sexual permissiveness in three Asian cities: effects of gender-role attitudes. J. Adolesc. Health. 2012;50:S18–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]