Abstract

BACKGROUND

There is controversy regarding the active agent responsible for alcohol addiction. The theory that ethanol itself was the agent in alcohol drinking behavior was widely accepted until acetaldehyde was found in the brain. The importance of acetaldehyde formation in the brain role is still subject to speculation due to the lack of a method to accurately assay the acetaldehyde levels directly. A highly sensitive GC-MS method to reliably determine acetaldehyde concentration with certainty is needed to address whether neural acetaldehyde is indeed responsible for increased alcohol consumption.

METHODS

A headspace gas chromatograph coupled to selected ion monitoring mass spectrometry was utilized to develop a quantitative assay for acetaldehyde and ethanol. Our GC-MS approach was carried out using a Bruker Scion 436-GC SQ MS.

RESULTS

Our approach yields limits of detection of acetaldehyde in the nanomolar range and limits of quantification in the low micromolar range. Our linear calibration includes 5 concentrations with a least square regression greater than 0.99 for both acetaldehyde and ethanol. Tissue analyses using this method revealed the capacity to quantify ethanol and acetaldehyde in blood, brain, and liver tissue from mice.

CONCLUSIONS

By allowing quantification of very low concentrations, this method may be used to examine the formation of ethanol metabolites, specifically acetaldehyde, in murine brain tissue in alcohol research.

Keywords: Ethanol, acetaldehyde, GC-MS, brain, liver

INTRODUCTION

Ethanol (EtOH) metabolism occurs via oxidation to acetaldehyde (AcH) and then to acetate, which is ultimately excreted as water and carbon dioxide. Acetaldehyde produced in the periphery cannot cross the blood brain barrier due to the abundance of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) within endothelial cells, which provide a metabolic barrier (Tabakoff et al., 1976). It was thought that ethanol could only marginally be metabolized in the central nervous system (CNS) due to the lack of the oxidizing enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) (Raskin and Sokoloff, 1968). Nevertheless, it has been determined that ethanol oxidation occurs in the brain by the peroxisomal enzyme catalase (2–4) and the microsomal cytochrome p450 enzyme isoform 2e1(Aragon et al., 1991, Aragon et al., 1985b, Cohen et al., 1980, Zimatkin et al., 2006). These findings support the earlier hypotheses that metabolites of ethanol could play a role in behavioral changes associated with drinking (Deng and Deitrich, 2008, Deitrich, 2004, Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002).

Although alcoholism cannot be completely modeled in rodents due to numerous factors, specific behaviors can be modeled. These behaviors include locomotion, sensitivity, motivation, etc., and each contributes one behavioral component to the understanding of the complexity of human alcoholism. Drinking preference is used to determine whether a mouse will freely consume ethanol when given the choice between ethanol and water. A variety of experimental approaches have been used to examine whether acetaldehyde levels in the CNS modulate drinking preference or behavior (Amit et al., 1986). For example, several studies utilized inhibitors of ethanol-oxidizing (Aragon et al., 1985a) and aldehyde-oxidizing enzymes (Deitrich et al., 1976, Deitrich and Erwin, 1971) to manipulate the concentration of acetaldehyde (Redila et al., 2000, Koechling and Amit, 1994, Eriksson, 1985). Other studies used mice that constitutively (Vasiliou et al., 2006, Amit et al., 1999) or were induced to (anti-catalase shRNA injected directly into the brain) (Israel et al., 2013, Tampier et al., 2013, Karahanian et al., 2011) express little to no brain catalase. Several factors hinder the direct measurement of acetaldehyde concentrations in rodent models; these include its low levels, high volatility, rapid metabolism by ALDH and artefactual acetaldehyde formation during sample processing (Eriksson et al., 1979). Acetaldehyde is ubiquitous in tissues at very low levels and it is ambient in blood and breath. Due to its high volatility, reliable measurement of acetaldehyde has been difficult (Eriksson, 2007), especially in tissue and blood of laboratory animals where the concentrations and sample volumes are thought to be quite low (Petersen and Tabakoff, 1979).

In order to quantify highly volatile compounds reliably, methods must be clearly validated. Here, we present a highly sensitive and reliable quantitative headspace gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) method capable of detecting ethanol and acetaldehyde in the low μM range in murine neuronal tissue and using low volumes (< 0.5mL). This method provides a reliable measure of low concentrations of acetaldehyde in mouse brain following intraperitoneal administration of ethanol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Ethanol, acetaldehyde, and toluene were all analytical grade (>99.9%, 98.5%, 99+% respectively) and purchased from Sigma Aldrich (ethanol and acetaldehyde), and Acros Organics (toluene) respectively.

Standard Preparation

Standard curve samples were prepared as previously described (Isse et al., 2002, Eriksson, 2001). Briefly, EtOH or AcH were prepared in 0.5 mL 0.6 N perchloric acid containing 40 mM thiourea and spiked with 5 μL 0.001% (v/v) toluene. Thiourea prevents artifactual AcH formation during analysis (Eriksson et al., 1984, Eriksson et al., 1980, Eriksson et al., 1977) and toluene is used as an internal standard. Toluene was chosen from compounds appropriate for use on the aquatic column based on retention time, peak symmetry and reaction and overlap with EtOH and AcH under the necessary conditions. To check for artefactual formation of AcH, tissues from untreated (saline injected) animals used for matrix were spiked with standard curve concentrations of EtOH and analyzed for AcH production. However, no AcH was detectable (data not shown). Serial dilutions of ethanol and acetaldehyde were performed at 4°C and a 300 μL of the resultant solution was transferred immediately into 20 mL headspace vials and sealed. Samples were stored at −20°C until eight minutes prior to run time (3 minutes prior to incubation period), at which time the vial was placed into the autosampler (Bruker, SHS40).

Sample Preparation

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado and were performed in accordance with published National Institutes of Health guidelines. Female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were injected with ethanol (2g/kg, i.p.) (EtOH) and sacrificed by CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation. Tissues were harvested immediately, with arterial blood collected from the left ventricle (50–200 μL) being spiked into ice cold 0.6 N perchloric acid (PCA), and brain and liver tissues flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. All samples were prepared the same day as harvesting as follows. The blood/PCA solution was centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 5 min. The frozen brain or liver tissue was pulverized using a mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen and then added to 1 mL PCA solution (1.7N for brain and 0.6 N for liver) containing 40 mM thiourea and toluene. These samples were then inverted to mix and centrifuged at 13000 rpm for 5 min. A 300 μL aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to a 20 mL glass vial and sealed. For each tissue, a standard curve was prepared (as described in standard curve preparation with modification) using each tissue collected from an untreated mouse as a matrix in their respective PCA concentration solution containing thiourea and toluene. Samples were stored at −20°C until eight minutes prior to run time (3 minutes prior to incubation period), at which time the vial was placed into the autosampler.

GC-MS

Adapted from a previously-reported headspace analysis (Duritz and Truitt, 1964, Eriksson et al., 1977, Cordell et al., 2013, Isse et al., 2005), our GC-MS approach was carried out using a Bruker Scion 436-GC SQ MS with SHS-40 autosampler using a medium polarity capillary column (25% diphenyl – 75% dimethylpolysiloxane, dimensions: 1 = 60 m. I.D. = 0.25 mm, dF=1 μM, Inertcap AQUATIC, GL Sciences). Vials were maintained at −20°C until insertion into the autosampler, at which time, they were heated to equilibrium at 60°C for 5 min with no agitation. Comparison of equilibration times beyond 5 min (i.e., up to 20 min) showed no significant increases in headspace concentrations of acetaldehyde or ethanol. A 1 mL headspace sample was injected into the column at a rate of 1 mL/min with the injector maintained at 200°C and the transfer line at 230 °C. The GC conditions were as follows: column temperature began at 38°C, was held for 8 min, then increased to 170°C at a rate of 40°C/min. It was held at 170°C for 5.7 min for a total of 17 min. The temperature was then decreased back to 38 °C at a rate of 43.3°C/min for a total method run-time of 20 min. The GC was operated with a 20:1 split ratio with a 1 mL/min continuous column flow rate using helium as a carrier gas.

The MS was operated in selected-ion monitoring mode (SIM); the ions of interest being monitored are listed in Table 1. Scan times were 105 ms for each compound, and 20 ms for the full scan. The transfer line to the MS was maintained at 250°C and the source temperature was 230°C.

Table 1. Summary of chromatography and spectrometry properties.

The retention time, qualifying and quantifying m/z, windows, and scan times are listed for each compound.

| Compound | Retention time (min) | Quantifying m/z | Qualifying m/z | Window (min) | Scan times (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acetaldehyde | 8.7 | 29 | 43, 44 | 1 | 105 |

| ethanol | 9.9 | 31 | 45, 46 | 1 | 52 |

| toluene | 16.4 | 91 | 92 | 1 | 105 |

An ethanol standard curve in tissue matrix was prepared and analyzed for artefactual acetaldehyde formation. The levels of acetaldehyde were no higher than the endogenous control.

Method validation

This method was validated using the FDA guidelines (FDA, 2011) as used in Cordell and colleagues (Cordell et al., 2013). Briefly, accuracy and precision need a minimum of 5 replicates of 3 concentrations within the expected range, including the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ). Accuracy means should not deviate greater than 15% from the actual value (except the LLOQ which should not deviate by more than 20%). Precision is analyzed intra- and inter-day and should not deviate by more than 15% of the coefficient of variation (CV) (except the LLOQ which should not deviate by more than 20% of the CV). Calibration curves were repeated 3 times for the expected range and CV was less than 15% for all standards (except the LLOQ which was less than 20%). Calibration curves include a blank (PCA only) and a blank with internal standard (PCA and toluene).

Data was analyzed using the logarithm of the ratio of integrated analyte peak (area under the curve, AUC) to integrated internal standard (toluene) peak (AUC). Precision was expressed as coefficient of variation and examined using intraday reproducibility of 5 replicate samples spiked at 3 different concentrations as follows: ethanol 100mM, 1mM, 0.01mM (LLOQ); acetaldehyde 0.1mM, 0.01mM, 0.001mM (LLOQ), with 100μL 5% BSA (included as a biological matrix). Inter-day precision was determined by repeating intra-day measurements over 2 days. The limit of detection was determined where the area under the curve was three-fold higher and lower limit of quantification was determined as five-fold higher than that of the blank sample.

RESULTS

Gas chromatography and mass spectrometry

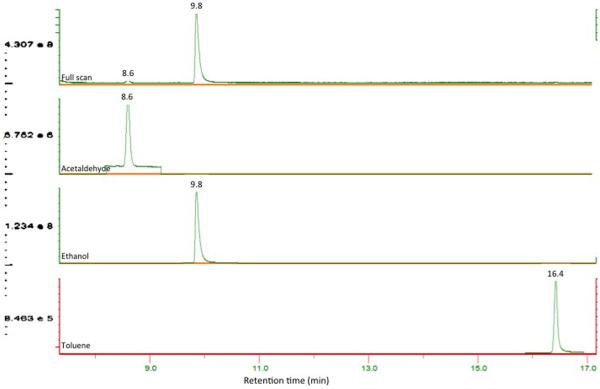

Gas chromatographic separation is necessary to achieve specificity. The chromatogram (Figure 1) shows the peaks from a mixture of AcH, EtOH, and toluene to give moderate final concentrations of 50 μM, 100 μM, and 0.0001% (v/v) respectively. The retention times were 8.6, 9.8, and 16.4 min, respectively. Toluene was chosen as an internal standard from ten similarly polar compounds that were appropriate for use on the Aquatic column. It was ideal for both EtOH and AcH stability as well as retention time and peak symmetry. Toluene did not react or overlap with EtOH or AcH under these conditions.

Figure 1. Spectra.

Full scan and individual spectra of acetaldehyde, ethanol, and toluene including retention time. X-axis indicates retention time (min) and the Y-axis is peak height (Cps). Numbers in blue text indicate the retention time at the respective peak height.

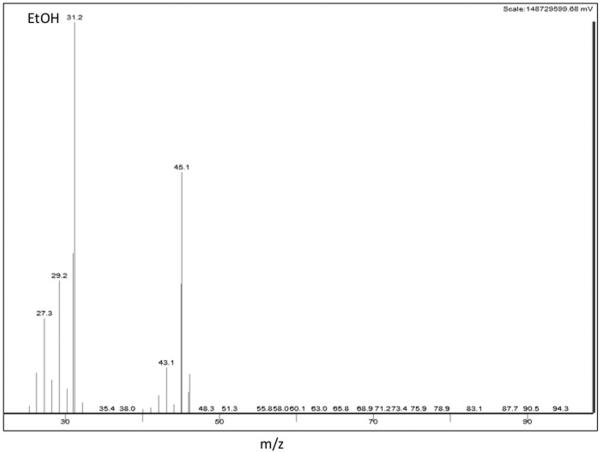

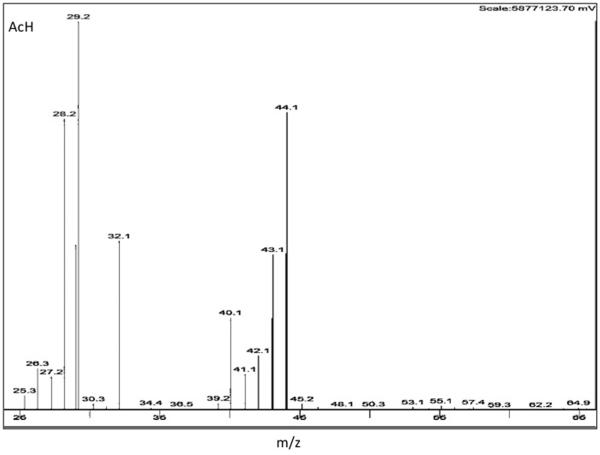

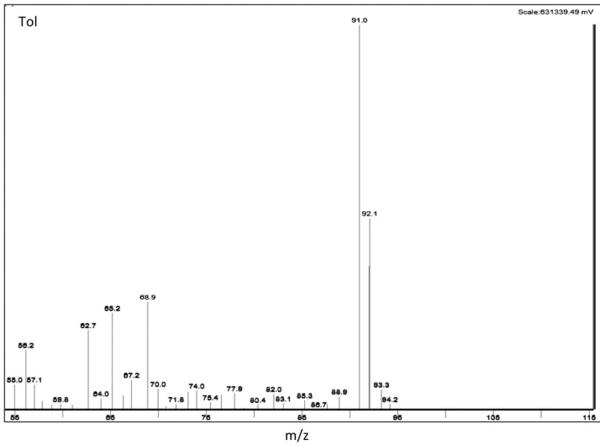

The quantitative and qualitative ions monitored are shown in Figure 2. For AcH, EtOH and toluene, the m/z for quantitation were 29, 31 and 91 (respectively), with each being the most abundant of the fragments for each compound.

Figure 2. Selected Ion monitoring.

Shown are ethanol (EtOH) (a), acetaldehyde (AcH) (b) and toluene (Tol) (c) ions. Largest values indicate quantitative ions 31, 29 and 91 m/z respectively.

Limits of detection and quantitation

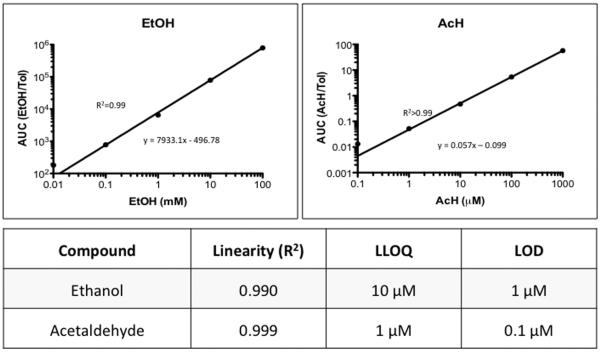

The limit of detection (LOD) for ethanol and acetaldehyde were 1μM (0.000046 mg/ml) and 0.1 μM (0.0000044 mg/mL) respectively. The LLOQ for EtOH was 10 μM (0.00046 mg/mL) and for AcH was 1 μM (0.000044 mg/mL) (Table 2), both of which are more sensitive than previously reported (Cordell et al., 2013). As described in the methods, this was determined by a signal-to-noise ratio of 5:1 (LLOQ) and 3:1 (LOD). Linearity, precision and accuracy were also taken into consideration.

Table 2. Method Precision.

Precision was measured using 3 concentrations of ethanol (EtOH) and acetaldehyde (AcH) (high (100 μM AcH, 100mM EtOH), moderate (50 μM AcH, 1mM EtOH), and lower limit of quantitation (1 μM AcH, 10 μM EtOH)) in 5 replicates to analyze intraday and subsequent interday precision to determine percent variance. Accepted precision %CV is below 15% for high (H) and moderate (M) values and below 20% for the LLOQ.

| Precision (%CV) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraday (n=5) | Interday (n=5) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Analyte concentration | LLOQ | M | H | LLOQ | M | H |

|

| ||||||

| Ethanol | 8.8 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 12.4 | 8.0 | 8.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Acetaldehyde | 7.7 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 8.1 | 3.1 | 3.9 |

Calibration curves and linearity

Calibration curves were repeated three times and plotted as mean ± standard deviation. To analyze the reproducibility, the % CV was calculated as described in the Methods section. For each concentration, the calibration curve %CV was < 5%, exceeding the guidelines. The linearity was determined using least squares regression (R2). Both EtOH and AcH had good linearity throughout the concentration ranges utilized, with R2 ≥ 0.99 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Calibration curve.

Five point calibration curves were generated and batch stability were confirmed by including a blank sample and a blank sample (PCA alone) and a blank with internal standard (PCA + Tol). Calibration curves were prepared using fresh ethanol (EtOH, top) or acetaldehyde (Ach, bottom) in 0.6 N perchloric acid (also used as blank) with 40 μM thiourea (which prevents artifactual acetaldehyde formation) and creating 1:10 serial dilutions. The EtOH and AcH concentrations utilized range from the LLOQ (0.1mM EtOH; 0.01μM AcH) to a high concentration. The logarithm area under the curve (AUC) to toluene AUC was used. Regression analysis revealed linear relationships for the standard curves for both EtOH (R2=0.99) and AcH (R2 = 0.999) and are listed in the table (bottom).

The lower limit of detection (LOD) and the LLOQ were measured as having three-fold and five-fold signal-to-noise ratio, respectively, relative to the blank sample and are listed in the table (bottom).

Precision and accuracy

The three concentrations tested for intra- and inter-day variation percent are shown in Table 3. High concentrations (H) were 100 mM and 1mM for EtOH and AcH respectively. Moderate concentrations (M) were 1mM and 50 μM for EtOH and AcH respectively. All concentrations for both EtOH and AcH were within the acceptable limits (15% and 20% for LLOQ); all but one were within 10% of CV. The three concentrations tested for accuracy are shown in Table 3. Both EtOH and AcH were between 90–110%; this exceeds the limits of 85–115% and 80–120% for the LLOQ. Recovery for EtOH and AcH were analyzed at 6 h at 4°C and overnight at −20°C, both of which had greater than 85% recovery (data not shown).

Table 3. Method Accuracy.

Accuracy was measured using 5 replicates of 3 different concentrations: high, moderate, and LLOQ (as used in precision estimation experiments). The average of each concentration was compared to the true value as determined by the calibration curve equation.

| Accuracy (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analyte concentration | LLOQ | M | H |

| Ethanol | 92.6 | 95.0 | 105.4 |

| Acetaldehyde | 101.5 | 98.5 | 102.4 |

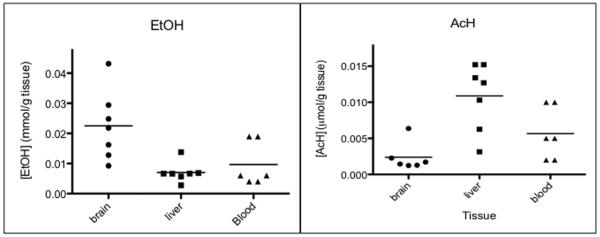

Tissue analysis

Levels of acetaldehyde and ethanol in blood, brain and liver obtained from ethanol-treated mice are shown in Figure 4. The levels of ethanol determined in the brain and liver are comparable to those published previously (Boehm et al., 2000, Gubner and Phillips, 2015, Isse et al., 2005). Therefore, our results in tissue confirm the reliability of the method. The ability to accurately measure AcH in the brain is novel. It is anticipated that this technique will now allow a thorough analysis the role of acetaldehyde in alcohol preference

Figure 4. Quantity of acetaldehyde and ethanol in blood, brain and liver in vivo.

Ethanol (EtOH) was administered (2g/kg, i.p.) to female C57BL/6 mice. Animals were sacrificed 20 min thereafter and tissues were collected and processed immediately. Quantification was completed within 2 d of sample collection. Data represent the individual responses from 6 animals.

DISCUSSION

The method described in the present study is sensitive enough to detect very low concentrations of ethanol and acetaldehyde in murine brain. Due to the volatility, rapid metabolism and low concentrations of acetaldehyde, measurement has remained difficult. This method validation was needed to verify the precision and accuracy to ensure analytically reliable measurement of acetaldehyde in animal studies. Importantly, the reliability of this method exceeds the guidelines used for method development.

In the present study, sample preparation has been optimized to obtain the most accurate measurement in tissue by decreasing time, temperature, and controlling for protein and artefactual formation as previously described (Eriksson et al., 1977). Using this technique, we have been able to analyze small concentrations in small volumes in tissue.

Cordell and colleagues successfully studied ethanol and other similar compounds in neonatal blood using microvolumes in human samples (Cordell et al., 2013). Quintanilla and colleagues designed a method using FID detection (Quintanilla et al., 2005), and Isse and colleagues designed a headspace GCMS method (Isse et al., 2005, Eriksson et al., 1977) based on the method designed by Eriksson and colleagues (Eriksson et al., 1977 Eriksson et al., 1977). Each of these studies provided methods, which we used as a foundation for our method development. Different method times and temperatures were employed to achieve ideal peak separation, SIM detection for increased sensitivity, a focus on sample preparation and storage for increased accuracy and precision, and inclusion of toluene as the most stable internal standard. To put into context, the precision of this method, using three technical replicates, we can detect a difference at the lower limit of quantitation of EtOH (LLOQ = 10 μM) and AcH (LLOQ = 1 μM) of ≈3 μM and ≈0.25 μM respectively. While toluene was the internal standard we selected, it would be interesting to compare the use of toluene to that of isotope labeled EtOH and AcH in the standard curve. To date, our method represents one of the most sensitive for neuronal acetaldehyde measurement at this time.

The main advantage of our method is the sensitivity and reliability of measurement of AcH with good separation of peaks in the long column and high peak resolution. Consistency of peak elution, combined with specificity of selected ion monitoring, gives distinct analyte resolution, along with reproducibility due to the use of toluene as an internal standard. This is advantageous because it allows quantification of small volumes and low concentrations, such as those obtained from mouse tissue.

The present technique will be exploited to elucidate whether AcH modulates drinking behavior by allowing the accurate measurement of the concentration of AcH in the brain post drinking-preference test. The goal was to develop a robust, reproducible and inexpensive GCMS method with a lower limit of detection for AcH measurement in tissue and thereby provide the basis for future experiments to elucidate dose-response, and concentration correlation between blood, brain, and liver. This method can also be used in to verify suppression of AcH levels following inhibitor or siRNA treatment, or genetic manipulations. Further, it can be used to explore how CNS AcH levels correlate with drinking behavior.

In summary, the detailed headspace GC-MS method provides a reliable and sensitive tool that fulfills the demand of quantification of EtOH and AcH in small concentrations and small volumes. This allows for the sensitive and reliable quantification of AcH in mouse brain and provides a cutting-edge technique to examine how neuronal AcH levels modulate of drinking preference.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported in part by NIH grants AA022057 and AA021724 (VV), and AA022146 (KSF)

REFERENCES

- AMIT Z, SMITH BR, ARAGON CM. Alcohol metabolizing enzymes as possible markers mediating voluntary alcohol consumption. Can J Public Health. 1986;77(Suppl 1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AMIT Z, SMITH BR, WEISS S. Catalase as a regulator of the propensity to ingest alcohol in genetically determined acatalasemic individuals from Israel. Addict Biol. 1999;4:215–21. doi: 10.1080/13556219971731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAGON CM, SPIVAK K, AMIT Z. Blockade of ethanol induced conditioned taste aversion by 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole: evidence for catalase mediated synthesis of acetaldehyde in rat brain. Life Sci. 1985a;37:2077–84. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90579-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAGON CM, STERNKLAR G, AMIT Z. A correlation between voluntary ethanol consumption and brain catalase activity in the rat. Alcohol. 1985b;2:353–6. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(85)90074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAGON CM, STOTLAND LM, AMIT Z. Studies on ethanol-brain catalase interaction: evidence for central ethanol oxidation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:165–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb01848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOEHM SL, 2ND, SCHAFER GL, PHILLIPS TJ, BROWMAN KE, CRABBE JC. Sensitivity to ethanol-induced motor incoordination in 5-HT(1B) receptor null mutant mice is task-dependent: implications for behavioral assessment of genetically altered mice. Behav Neurosci. 2000;114:401–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN G, SINET PM, HEIKKILA R. Ethanol oxidation by rat brain in vivo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1980;4:366–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb04833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORDELL RL, PANDYA H, HUBBARD M, TURNER MA, MONKS PS. GC-MS analysis of ethanol and other volatile compounds in micro-volume blood samples--quantifying neonatal exposure. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2013;405:4139–47. doi: 10.1007/s00216-013-6809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH RA. Acetaldehyde: deja vu du jour. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:557–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH RA, ERWIN VG. Mechanism of the inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase in vivo by disulfiram and diethyldithiocarbamate. Mol Pharmacol. 1971;7:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEITRICH RA, TROXELL PA, WORTH WS. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase in brain and liver by cyanamide. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976;25:2733–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENG XS, DEITRICH RA. Putative role of brain acetaldehyde in ethanol addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1:3–8. doi: 10.2174/1874473710801010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DURITZ G, TRUITT EB., JR A Rapid Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Acetaldehyde and Ethanol in Blood Using Gas Chromatography. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1964;25:498–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ. Endogenous acetaldehyde in rats. Effects of exogenous ethanol, pyrazole, cyanamide and disulfiram. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34:3979–82. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ. The role of acetaldehyde in the actions of alcohol (update 2000) Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:15S–32S. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ. Measurement of acetaldehyde: what levels occur naturally and in response to alcohol? Novartis Found Symp. 2007;285:247–55. doi: 10.1002/9780470511848.ch18. discussion 256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ, ATKINSON N, PETERSEN DR, DEITRICH RA. Blood and liver acetaldehyde concentrations during ethanol oxidation in C57 and DBA mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:2213–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ, HILLBOM ME, SOVIJARVI A. Difficulties in measuring human acetaldehyde levels. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1979;4:148. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(79)90058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ, HILLBOM ME, SOVIJARVI AR. Difficulties in measuring human blood acetaldehyde concentrations during ethanol intoxication. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1980;126:439–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3632-7_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERIKSSON CJ, SIPPEL HW, FORSANDER OA. The determination of acetaldehyde in biological samples by head-space gas chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1977;80:116–24. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90631-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA . In: Guidance for Industry Process Validation: General Principles and Practices. FDA, editor. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- GUBNER NR, PHILLIPS TJ. Effects of nicotine on ethanol-induced locomotor sensitization: A model of neuroadaptation. Behav Brain Res. 2015;288:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.03.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISRAEL Y, RIVERA-MEZA M, KARAHANIAN E, QUINTANILLA ME, TAMPIER L, MORALES P, HERRERA-MARSCHITZ M. Gene specific modifications unravel ethanol and acetaldehyde actions. Front Behav Neurosci. 2013;7:80. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISSE T, MATSUNO K, OYAMA T, KITAGAWA K, KAWAMOTO T. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 gene targeting mouse lacking enzyme activity shows high acetaldehyde level in blood, brain, and liver after ethanol gavages. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1959–64. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187161.07820.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISSE T, OYAMA T, KITAGAWA K, MATSUNO K, MATSUMOTO A, YOSHIDA A, NAKAYAMA K, NAKAYAMA K, KAWAMOTO T. Diminished alcohol preference in transgenic mice lacking aldehyde dehydrogenase activity. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12:621–6. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200211000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARAHANIAN E, QUINTANILLA ME, TAMPIER L, RIVERA-MEZA M, BUSTAMANTE D, GONZALEZ-LIRA V, MORALES P, HERRERA-MARSCHITZ M, ISRAEL Y. Ethanol as a prodrug: brain metabolism of ethanol mediates its reinforcing effects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:606–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOECHLING UM, AMIT Z. Effects of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole on brain catalase in the mediation of ethanol consumption in mice. Alcohol. 1994;11:235–9. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSEN DR, TABAKOFF B. Characterization of brain acetaldehyde oxidizing systems in the mouse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1979;4:137–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(79)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QUINTANILLA ME, TAMPIER L, SAPAG A, ISRAEL Y. Polymorphisms in the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (Aldh2) determine peak blood acetaldehyde levels and voluntary ethanol consumption in rats. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:427–31. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RASKIN NH, SOKOLOFF L. Brain alcohol dehydrogenase. Science. 1968;162:131–2. doi: 10.1126/science.162.3849.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REDILA VA, SMITH BR, AMIT Z. The effects of aminotriazole and acetaldehyde on an ethanol drug discrimination with a conditioned taste aversion procedure. Alcohol. 2000;21:279–85. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(00)00096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODD-HENRICKS ZA, MELENDEZ RI, ZAFFARONI A, GOLDSTEIN A, MCBRIDE WJ, LI TK. The reinforcing effects of acetaldehyde in the posterior ventral tegmental area of alcohol-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72:55–64. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00733-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TABAKOFF B, ANDERSON RA, RITZMANN RF. Brain acetaldehyde after ethanol administration. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976;25:1305–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMPIER L, QUINTANILLA ME, KARAHANIAN E, RIVERA-MEZA M, HERRERA-MARSCHITZ M, ISRAEL Y. The alcohol deprivation effect: marked inhibition by anticatalase gene administration into the ventral tegmental area in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1278–85. doi: 10.1111/acer.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VASILIOU V, ZIEGLER TL, BLUDEAU P, PETERSEN DR, GONZALEZ FJ, DEITRICH RA. CYP2E1 and catalase influence ethanol sensitivity in the central nervous system. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2006;16:51–8. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000182777.95555.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIMATKIN SM, PRONKO SP, VASILIOU V, GONZALEZ FJ, DEITRICH RA. Enzymatic mechanisms of ethanol oxidation in the brain. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1500–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]