Abstract

BACKGROUND

Stress triggers impulsive and addictive behaviors, and alcoholism has been frequently associated with increased stress sensitivity and impulse control problems. However, neural correlates underlying the link between alcoholism and impulsivity in the context of stress in patients with alcohol use disorders (AUD) have not been well studied.

METHOD

The current study investigated neural correlates and connectivity patterns associated with impulse control difficulties in abstinent AUD patients. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, brain responses of 37 AUD inpatients and 37 demographically-matched healthy controls were examined during brief individualized imagery trials of stress, alcohol-cue and neutral-relaxing conditions. Stress-related impulsivity was measured using a subscale score of impulse control problems from Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS).

RESULTS

Impulse control difficulties in AUD patients were significantly associated with hypoactive response to stress in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VmPFC), right caudate, and left lateral PFC (LPFC) compared to the neutral condition (p<0.01, whole-brain corrected). These regions were used as seed regions to further examine the connectivity patterns with other brain regions. With the VmPFC seed, AUD patients showed reduced connectivity with the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) compared to controls, which are core regions of emotion regulation, suggesting AUD patients’ decreased ability to modulate emotional response under distressed state. With the right caudate seed, patients showed increased connectivity with the right motor cortex, suggesting increased tendency toward habitually driven behaviors. With the left LPFC seed, decreased connectivity with the dorsomedial PFC (DmPFC), but increased connectivity with sensory and motor cortices were found in AUD patients compared to controls (p<0.05, whole-brain corrected). Reduced connectivity between the left LPFC and DmPFC was further associated with increased stress-induced anxiety in AUD patients (p<0.05, with adjusted Bonferroni correction).

CONCLUSION

Hypoactive response to stress and altered connectivity in key emotion regulatory regions may account for greater stress-related impulse control problems in alcoholism.

Keywords: stress, impulse control, alcoholism, prefrontal cortex, caudate

Introduction

Impulsivity has been associated with hazardous drinking, inappropriate decision making, and disinhibited motor-related behaviors (for a review, (Potenza and de Wit, 2010)). It has also been shown to predict alcohol use over time (Littlefield, et al., 2010) and increase risk taking behaviors, especially in the context of alcohol use (Rose, et al., 2014).

In particular, impulsivity triggered by emotional stress has been suggested as a critical factor in predicting alcoholism and protracted treatment response in patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD) (Fox, et al., 2008). Provocative stress accompanied with high emotional arousal increases negative urgency, impulsivity, and dyscontrolled behaviors (Seo and Sinha, 2011). In response to stress, greater risk-taking tendencies, increased reward-seeking, and addictive behaviors have been reported (Sinha, 2008; Stojek and Fischer, 2013). In AUD patients, stress has been consistently identified as a risk factor increasing alcohol-drinking urges, vulnerability to alcoholism, and subsequent relapse after treatment (Seo, et al., 2013; Sinha, et al., 2011). Individuals with greater stress and emotional problems comorbid with addiction tend to have a more extreme form of impulsive behavior, such as aggression (for a review, (Seo, et al., 2008)). In addition, a study found that an interaction between high stress and impulsivity synergistically influence an individual toward greater hazardous alcohol-drinking behaviors (Fox, et al., 2010). However, despite the consistent indication of significant roles of stress and impulsivity in alcoholism (Potenza and de Wit, 2010; Seo, et al., 2013; Sinha, et al., 2009; Sinha, et al., 2011), no prior study has examined neural correlates and relevant connectivity patterns underlying stress-related impulse control problems in AUD patients.

Impulse control problems under stress involves difficulties in modulating negative emotional response and inhibiting impulsive behaviors (Gratz and Roemer, 2004). This concept implies impaired regulatory control over emotional and motor-related behaviors in response to stressful events. Previous studies have also suggested that dysfunction in brain regions of emotion regulation could be an important neural correlate of stress and impulsivity, including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VmPFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Li and Sinha, 2008). The VmPFC is involved in impulsivity and negative urgency in social drinkers (Cyders, et al., 2014). In AUD patients, the VmPFC has been associated with stress-induced alcohol craving, and hypoactive VmPFC response to stress prospectively predicted alcohol relapse severity following treatment (Seo, et al., 2013). The VmPFC has close anatomical and functional connections with emotional processing regions such as the amygdala and striatum via the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) (Carmichael and Price, 1995). The ACC plays a role in monitoring emotional response and adjusting socio-emotional behaviors (Botvinick, 2007), whereas the VmPFC is involved in executive control of emotion (Davidson, et al., 2000; Etkin, 2010; Urry, et al., 2006) and visceromotor control (Bechara and Damasio, 2002), indicating the importance of the interplay between these two regions in regulating emotion, impulsivity, and behavioral control.

In addition, the role of the DLPFC has been indicated in cognitive and emotional control (Asplund, et al., 2010; Kim and Hamann, 2007; MacDonald, et al., 2000). The DLPFC is connected with the medial PFC, motor, and parietal association cortices, thereby integrating sensory and motor information from the sensory and motor cortices (Selemon and Goldman-Rakic,1988) and sending regulatory instruction to the medial PFC to modulate emotion and stress response (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Seo and Sinha, 2011). With high intensity stressors, prefrontal cortex dysfunction, especially in the DLPFC and impaired high-order functioning including working memory ability have been reported (for a review, (Arnsten, 2009)). Thus, it is likely that stress-related impulse control may involve neural response to stress in the core circuit of emotion regulation and its interaction with other brain regions. To fully understand neural mechanisms underlying impulse control difficulties in alcoholism, it is crucial to identify brain correlates associated with impulse control and their functional connectivity with other brain regions in the context of emotionally challenging situations (e.g., stress or alcohol cue).

Accordingly, the purpose of the current study is to identify neural correlates of impulse control during emotionally challenging states such as stress and alcohol cue in AUD patients using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). We further aim to examine the integrity of functional connectivity between the neural circuit of impulse control and other brain regions in AUD patients. As stress and alcohol cue exposure are regarded as emotionally challenging situations that contribute to alcoholism risk (Breese, et al., 2011; Sinha, et al., 2011), we examined the alcohol cue condition in addition to the stress condition. To induce stress and alcohol cue, we used an well-established, brief individualized imagery method (Sinha, 2009) in 37 recovering AUD inpatients and 37 demographically-matched healthy controls. For impulsivity, we used a subscale score of the Difficulties in Impulse Control (IMPULSE) measure from the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), a validated measure in detecting stress-related impulse control problems in patients with AUD and other addictive disorders as well as in predicting alcohol treatment response (Fox, et al., 2007; Fox, et al., 2008). As the IMPULSE score has been found to be a sensitive measure detecting those with more severe alcohol pathology and poor treatment response within AUD individuals, we aimed to identify neural correlates in AUD patients first and use them as seed regions for connectivity analysis. Then, these connectivity maps were compared with healthy controls. This analytic approach was utilized to specify neural correlates and connectivity patterns directly contributing to impulse control difficulties in alcoholism. We hypothesized that prefrontal regions involved in emotion regulation (e.g., VmPFC, ACC, and DLPFC) would be associated with stress-related impulse control difficulties in AUD patients. Further we anticipated that altered connectivity between these regions and other brain areas involved in emotional and motor behaviors would also be found in AUD patients.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Thirty-seven alcohol-dependent patients, who were 4–8 weeks abstinent, participated in this study. AUD patients resided in an inpatients treatment facility for 5 weeks and completed the MRI scan after week 4 of admission. A current diagnosis of alcohol dependence were determined by self-reported use of alcohol, urine toxicology testing and a Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (SCID-I (First, et al., 2002)). Additionally thirty-seven healthy participants, who were matched on age, intelligence, handedness (right-handed), and gender ratio, were recruited via community newspaper, flyers and web advertising. The healthy controls reported consuming 25 drinks or less per month and did not meet current or lifetime abuse or dependence criteria for alcohol or any illicit drug. Participants taking current medications were excluded, and thus there was no group difference in medication status. All participants were free of current alcohol or drug use during baseline assessment and the fMRI session, as verified by negative urine toxicology and breathalyzer screens. This sample consists about 89% of an overlapping data set reported in a prior study, which focused on the task-based fMRI results and association to alcohol relapse (Seo, et al., 2013) (see supplemental information for detailed methods).

Impulse Control Measure

Impulse control difficulties were measured by a subscale score of the Difficulties in Impulse Control (IMPULSE) from a 41-item version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; (Gratz and Roemer, 2004)). The IMPULSE reflects difficulties regulating one’s behavior during negative and stressful emotional states and inhibiting unintended behavior (Gratz and Roemer, 2004). Items were scored using a 5-point likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = almost half the time, 4 = most of the time, 5 = almost always). Previous research has demonstrated the validity of the IMPULSE scale; it was predictive of addictive disorders and accounted for protracted, relapse vulnerability in addicted populations (e.g., (Fox, et al., 2007)) including alcohol-dependent individuals (Fox, et al., 2008). AUD participants completed the DERS questionnaire during the first week of inpatient treatment, while healthy control participants completed them at an intake session prior to the MRI scan.

Guided imagery script development

A well-validated, individualized guide imagery method (Sinha et al., 2009; 2011; Seo et al., 2013; Potenza et al., 2012) was used to induced stress, alcohol cue and neutral-relaxing conditions (see supplemental information for more details). During the session prior to the fMRI scan, six individually-tailored imagery scripts (2 scripts per condition) were developed based on the experience of participants via Scene Construction Questionnaires (Sinha, 2009). For stress scripts, participants described, “a situation that made them sad, mad, upset and which in the moment they could do nothing to change it” and rated the stressfulness of scenarios on a 10-point Likert scale; only situations rated 8 or above were used for script development. The alcohol cue script was related to experience of alcohol anticipation and consumption based on response to the prompt, “please tell us about a recent situation when you really wanted an alcoholic drink and then you went ahead and had one.” Alcohol-cue situations related to the context of negative affect or psychological distress were excluded. Neutral scripts were based on personal experience of neutral-relaxing situations, such as relaxing at the beach or reading on a Sunday afternoon. The script length, style, and content format were standardized across conditions (Sinha, 2009). During the MRI scan, each two-minute script was audio-taped and played through headphones, and the same procedure was followed across all script runs and across subjects, as is typical of MRI experiments. The order of presentation was randomly assigned across participants. To minimize variability in imagery ability, all participants completed a structured relaxation and imagery training prior to the MRI scan (Sinha, 2009). Efficacy of the imagery manipulation was verified by equivalent levels of mental imagery ability and post-imagery vividness ratings across groups (see supplemental information).

MRI data acquisition

During a 1.5-hour MRI session, MRI data were acquired using a 3T Siemens Trio MRI system equipped with a standard quadrature head coil, using T2*-sensitive gradient-recalled single shot echo planar pulse sequence. Anatomical images were collected with spin echo imaging in the axial plane parallel to the AC-PC line with TR = 300 msec, TE = 2.5 msec, bandwidth = 300 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 60 degrees, field of view = 220 × 220 mm, matrix = 256 × 256, 32 slices with slice thickness = 4mm with no gap. A slice thickness of 4 mm was utilized to consider the optimum level of signal-to-noise ratio; this is common in other fMRI studies, but could cause suboptimal tissue specificity. Functional MRI images were obtained using a single-shot gradient echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence. Thirty-two axial slices parallel to the AC-PC line covering the whole brain were acquired with TR = 2,000 msec, TE = 25 msec, bandwidth = 2004 Hz/pixel, flip angle = 85 degrees, field of view = 220×220 mm, matrix = 64×64, 32 slices with slice thickness = 4mm and no gap. Finally, a high-resolution 3D Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) sequence was used to obtain sagittal images for multi-subject registration (TR = 2530 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.34 ms; bandwidth = 180 Hz/pixel; flip angle (FA) = 7°; slice thickness = 1mm; field of view = 256×256 mm; matrix = 256 × 256).

fMRI trials

An fMRI block design was used, with each block consisting of 5 minute fMRI trial. There were a total of 6 fMRI task runs with 2 runs in each condition (Stress, Alcohol-cue, Neutral-relaxing), which were presented in a counterbalanced order. Each run lasted for 5 min including a 1.5-minute quiet baseline, a 2.5-minute imagery (2 minute of read imagery and 0.5 minute of quiet imagery) and a 1 minute quiet recovery period. During baseline, participants were asked to stay still without engaging in mental activity. The purpose of the baseline period was to induce a baseline state with no-task demand. This state is different from the neutral-relaxing condition, which is an active comparison condition for a specific task-related, relaxing imagery state. During recovery, participants were instructed to “stop imagining and lay still.” The order of three script types (stress, alcohol cue, neutral) was randomized across participants. Scripts from the same condition were not presented consecutively, and each script was presented only once for a participant. Before and after each fMRI trial, anxiety and craving ratings were collected using a 10-point verbal analog scale (1=not at all, 10=extremely high). For anxiety ratings, participants were asked to rate how “tense, anxious and/or jittery” they felt, and for craving ratings, to rate the intensity of “desire to drink alcohol at that moment”. To normalize any anxiety or craving from prior trials, participants engaged in a 2-minute progressive muscle relaxation between fMRI trials. Progressive relaxation is a procedure focusing on relaxing physical muscle tension, which does not involve mental imagery. No MRI image acquisition was performed during this procedure. After relaxation, ratings returned to baseline as verified by no statistical difference in baseline ratings across trials. The total task time was approximately one hour including the 6 functional runs, progressive relaxation between runs, and ratings.

fMRI data analysis

Raw fMRI data were converted from Digital Imaging and Communication in Medicine format to Analyze format using XMedCon (Nolfe, 2003). The first ten images of each trial were discarded to achieve a steady-state equilibrium between radio-frequency pulsing and relaxation. There were a total of 150 frames per run (baseline=45 frames, 2.5 imagery=75 frames, and recovery=30 frames). For the 2.5 imagery period in each condition per subject, there were 150 frames available, as there were two runs per condition (a total of 5550 frames for each group of 37 individuals). Images were motion-corrected for 3 translational and 3 rotational directions (Friston, et al., 1996) using Statistical Parametric Mapping 5, with any trial with linear motion exceeding 1.5 mm or having a rotation greater than 2 degrees being removed. The recovery period was excluded from the data analysis, due to the possibility of carryover effects from the imagery period.

At the individual level, General Linear Model (GLM) anlaysis was conducted on each voxel in the entire brain volume with a task-specific regressor (2.5 imagery compared to a 1.5 minute baseline) using Yale BioImageSuite (http://www.bioimagesuite.org) (Duncan, et al., 2004). To consider potential variability in baseline fMRI signal, drift correction was included in the GLM with drift regressors used to remove the mean time course, liner, quadratic, and cubic trends for each run. Functional images were spatially smoothed using a 6 mm Gaussian kernel and individually normalized to generate beta-maps in the acquired space (3.44mm × 3.44mm × 4mm). To account for individual anatomical differences, three registrations were sequentially implemented using the BioImageSuite: linear individual registration of raw data into 2D anatomical image, the 2D to 3D (1×1×1 mm) linear registration, and a non-linear registration to a reference 3D image, which is the Colin27 Brain (Holmes, et al., 1998) in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space.

Group analysis was conducted with AFNI (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov, (Cox, 1996)) using a random mixed effects model. A 2 × 3 ANOVA (group by condition) was carried out with group (AUD, Controls) as the between-subject fixed-effect factor, condition (neutral/alcohol cue/stress) as the within-subject fixed-effect factor, and subject as the random-effect factor (see Supplemental information for this result). Two tailed t-tests were further implemented to examine group differences in the task effects of interest (Stress-Neutral, Alcohol cue-Neutral; supplemental figure 2). A FamilyWise Error rate (FWE) correction for multiple comparisons was applied using Monte Carlo simulations (Xiong, et al., 1995) conducted with the AFNI AlphaSim program. In the Monte Carlo simulation, we used a smoothing kernel of 6mm and a connection radius of 6.296mm on 3.44mm × 3.44mm × 4mm voxels with 1500 iterations, applied to whole brain volume. The minimum cluster size determined was 6237 mm3 at a cluster-level significance α<0.05 for a voxel-wise threshold of p<0.05 and 1458 mm3 at a cluster-level significance α<0.01 for a voxel-wise threshold of p<0.01 (two-tailed).

To investigate the relationship between IMPULSE and task-related brain activity, whole-brain correlation analysis was conducted using BioImageSuite with the application of AFNI AlphaSim FWE correction for multiple comparisons. We used a whole-brain correlation approach, not the task-related ROI correlation, as we aim to identify brain regions directly associated with IMPULSE scores across all brain areas. The resulting neural correlates were then used as seed regions to further examine the pattern of their connectivity with other brain regions. We expected that seed regions based on the correlation results would provide specific connectivity information underlying impulse control problems in AUD subjects. Seed-based functional connectivity analysis was performed with BioImageSuite. Reference regions were functionally defined from significant brain regions revealed in the whole brain correlation map with IMPULSE scores. These regions were inversely transformed into individual subject space (using the inverse transforms from the GLM analysis). For each subject, the time-course of the inversely transformed reference region was computed as the average time-course across all pixels within the reference region. Using a whole-brain voxel-wise Pearson correlation, the time-course was correlated with the time-courses of all the other voxels in the brain during the homogeneous condition with seed regions, fisher transformed to z-values, averaged across runs and finally spatially smoothed with a 6mm Gaussian filter. To examine group differences, connectivity maps were entered into two-sample t-tests. As smoking is common in AUD individuals (approximately 60 % in those with alcohol dependence (Falk, et al., 2006)), group difference were first examined using t-tests. Then, in order to understand patterns uniquely associated with AUD, we additionally examined group differences with smoking status used as a covariate.

To best identify neural correlates and be properly conservative, a threshold of p < 0.01 was applied for whole-brain correlation analyses with the IMPULSE measure, and p < 0.05 was used to examine group differences in functional connectivity maps.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics of AUD patients and healthy controls are presented in Table 1. Group differences in terms of gender, race, and mental health history were examined using chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests for all other continuous measures. No significant group differences were found in demographics based on age, gender, race, Shipley IQ, marijuana use, and mental health history, except for alcohol use behaviors (years of use, amount and days of use for the past 30 days) and smoking status. AUD participants showed greater difficulties in controlling impulsivity, as measured by higher IMPULSE scores (t=2.48, p=.016) compared with healthy controls (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | AUD inpatients (n = 37) | Healthy Controls (n = 37) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.2 (7.9) | 34.3 (8.6) |

| Gender (% female) | 8 (22%) | 14 (38%) |

| Shipley IQ | 109.7 (8.2) | 111.6 (8.0) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 23 (62%) | 23 (62%) |

| Afro-american | 13 (35 %) | 14 (38 %) |

| Other | 1 (3%) | 0 (0 %) |

| DERS Impulse Control score* | 10.22 (4.64) | 8.08 (2.45) |

| Alcohol Use | ||

| Years of Use*** | 17.5 (8.8) | 8.0 (8.4) |

| Amount (# drinks, past 30 days) *** | 435.8 (296.7) | 12.5 (13) |

| Days of Use (Past 30 Days) *** | 19.5 (9.8) | 4.4 (4.9) |

| Smoking Statusa*** | 32 (86%) | 5 (14%) |

| Marihuana Use Disorderb | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mental Health History | ||

| Lifetime Prevalence of PTSD | 4 (11%) | 2 (5%) |

| Lifetime Other Anxiety Disorders | 6 (16%) | 3 (8%) |

| Lifetime Major Depression | 6 (16%) | 4 (11%) |

Note:

p<0.05,

p<0.001;

Standard deviation is denoted in parenthesis (except for %). There is no group difference in demographics except for alcohol use, smoking status, and impulsivity. For AUD patients, alcohol use data reflect base level prior to inpatient admission.

DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale;

smokers vs. non-smoker;

current marihuana use disorder.

All AUD inpatients were abstinent for 4 weeks, and there was no alcohol or drug use during intake and fMRI sessions.

Group differences in brain activity, anxiety, and alcohol craving ratings

As previously reported (Seo et al., 2013), significant group differences were found between AUD and healthy individuals in task-related brain activity and in subjective ratings of anxiety and craving. Results are presented in the supplemental section (see supplemental figures 1 and 2, and supplemental tables 1 and 2). Compared with healthy controls, AUD patients endorsed significantly higher anxiety ratings during alcohol cue (t=3.6, p<.01) and greater alcohol craving during both the stress (t=2.3, p<.05) and alcohol cue (t=2.4, p<.05) conditions (see supplemental figure 1). There were no significant correlations between the IMPULSE measure and subjective anxiety or craving ratings in both the AUD and HC groups. fMRI results indicated that both AUD and HC groups showed increased activity in the medial PFC, ACC/PCC, ventrolateral PFC, insula, precuneus, temporal lobe, and pre-/post-central gyri during stress and alcohol cue exposures relative to the neutral condition (supplemental table 2). Compared with controls, AUD patients showed decreased activity in these areas during S-N and AC-N conditions, with additional hypoactive response in the ventral striatum, right lateral PFC and temporal lobe in AC-N (p<.01 whole-brain FWE corrected; see supplemental figure 2 and table 1).

Correlations between brain activity and IMPULSE score

Whole brain correlation analysis was conducted between IMPULSE scores during stress-neutral and alcohol cue-neutral conditions. The result revealed significant neural correlates associated with IMPULSE scores during stress exposure. There were significantly negative correlations in AUD patients between IMPULSE and brain activity in the VmPFC (BA 10), right caudate, and left LPFC involving the DLPFC during stress-neutral (p<.01, whole-brain FWE corrected; see figure 1 and table 1); hypoactive response to stress in these regions was associated with greater difficulties with impulse control problems in AUD patients. The left LPFC does not include the anterior insula and is limited to the lateral PFC region (BA44, 45, 46). No significant correlation was found in the alcohol cue relative to the neutral condition. Healthy controls did not show any brain regions significantly correlated with their impulse control problems in any of these conditions that survived whole-brain correction for multiple comparisons. To examine group differences, correlation coefficients were converted to z scores using Fisher’s z transformation, and two samples t-tests were performed using these z scores. No group differences were found with correction for multiple comparisons, suggesting that the patterns may be continuous, but more manifest in AUD patients.

Figure 1.

Whole-brain voxel-based correlation results and scatter plots showing negative correlations between impulse control problems and stress induced brain activity in AUD patients. Hypoactive response to stress in the VmPFC (r= −.55), right caudate (r= −.42), and left LPFC (r = −.46) relative to the neutral condition was significantly associated with greater difficulties controlling impulsivity (whole brain FWE corrected at p < 0.01). Blue/purple colors = negative correlations. VmPFC = Ventromedial prefrontal cortex; LPFC = left prefrontal cortex; L= Left, R = Right. MNI coordinates were used. Note: there was no outlier in this scatterplot. In the initial analysis, there was one extreme value; the correlation result was still significant even after removing this value. Scatterplots and r values were presented after the Winsorization to reduce the influence of this value.

To account for the influence of an outlier in the correlation, the Winsorization (Chen and Dixon, 1972; Dixon, 1960) was implemented. There was one extreme value (with a Cook’s Distance score greater than 1) in the correlation between IMPULSE and brain activity. The correlation result was still significant even after removing this value. To reduce the influence of this value, the r value and scatterplots was presented in Figure 1 after the Winsorization; the correlation r value was reported after an extreme value was reigned in to the value of the next highest score to reduce its influence.

Functional connectivity with correlates of IMPULSE

To investigate connectivity patterns associated with brain regions involved in stress-related impulse control difficulties, functional connectivity analysis was conducted with three brain correlates of the IMPULSE measure (VmPFC, right caudate, left LPFC) as seed regions (see table 2) during the stress condition. These seed volumes were aligned with current methods for functional connectivity published in other studies (Craddock, et al., 2012; Finn, et al., 2015; Power, et al., 2011). Group differences in functional connectivity patterns were found during stress exposure (p<0.05 whole brain FWE corrected). In figures 2–4, brain regions showing greater connectivity in HC vs. AUD were indicated with blue/purple colors, and brain regions with greater connectivity in AUD vs. HC were indicated in yellow/red colors. With the VmPFC (BA10) seed, AUD participants showed significantly reduced connectivity with the rostral ACC (BA 24/32) relative to healthy controls (Figure 2). With the right caudate seed, AUD patients showed increased connectivity with right motor cortex compared to controls (Figure 3). In addition, when the left LPFC was used as a seed region (Figure 4), AUD participants showed significantly reduced connectivity with the dorsomedial PFC (DmPFC), but increased connectivity with sensory and motor cortices including post-/pre- central gyrus and middle occipital gyrus (p<0.05 whole brain corrected). In addition, group differences were examined using smoking status as a covariate; the results indicated significant differences in the left DLPFC connectivity only with the DmPFC and sensory/motor cortices (Figure 4), not in the VmPFC and right caudate connectivity.

Table 2.

Neural Correlates of Impulse Control Difficulties

| Neural Correlates | Laterality | BA | Coordinates

|

Volume (mm3) | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | |||||

| Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex | L, R | 10 | 9 | 50 | 6 | 5186 | −0.55 |

| Caudate | R | - | 13 | 14 | 11 | 1650 | −0.42 |

| Lateral Prefrontal Cortex | L | 44, 45, 46 | −37 | 32 | 17 | 3430 | −0.46 |

Significant correlations at p<0.01 with brain activity during stress relative to neutral condition Whole-brain FWE corrected; Lat = laterality; L = left; R = right; BA = Brodmann’s area.

Figure 2.

Functional connectivity with the VmPFC seed. When the VmPFC was used as a seed region, significant group difference was found in connectivity between the VmPFC and ACC during stress (p < 0.05 whole-brain FWE corrected); AUD patients showed significantly reduced connectivity between the VmPFC and ACC compared with healthy controls. blue/purple colors = decreased connectivity, yellow/red = increased connectivity; In AUD-HC map, blue/purple = AUD < HC. VmPFC = Ventromedial prefrontal cortex; ACC = Anterior cingulate cortex; AUD = Alcohol Use Disorder, HC = healthy controls, L= Left, R = Right. MNI coordinates were used.

Figure 4.

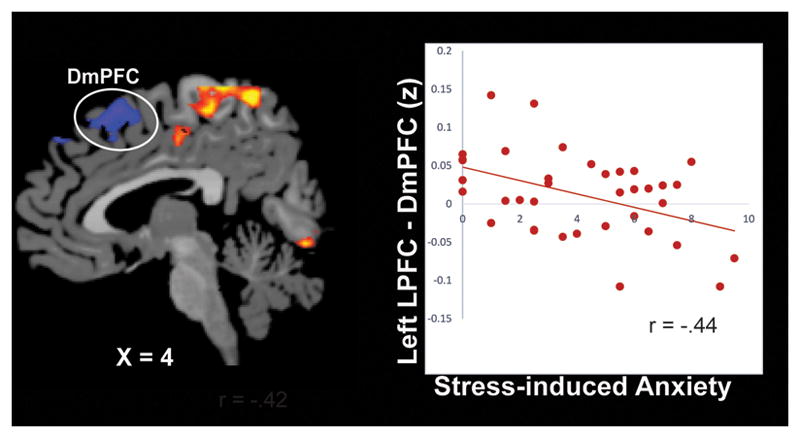

Functional connectivity with the left lateral PFC seed. When the left LPFC was used as a seed region, significant group difference was found in connectivity between the left DLPFC and the DmPFC and sensory motor cortices (including pre-/post- central gyrus, and occipital gyrus) during the stress condition (p < 0.05 whole-brain FWE corrected); AUD patients showed significantly reduced connectivity between the left DLPFC and DmPFC, but increased connectivity between the left DLPFC and sensory motor cortices compared with healthy controls. blue/purple colors = decreased connectivity, yellow/red = increased connectivity; In AUD-HC map, blue/purple = AUD < HC, yellow/read = AUD > HC. DmPFC= Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex; G = Gyrus, L= Left, R = Right. MNI coordinates were used.

Figure 3.

Functional connectivity with the right caudate seed. When the right caudate was used as a seed region, significant group difference was found in connectivity between right caudate and motor cortex during stress (p < 0.05 whole-brain FWE corrected); AUD patients showed significantly increased connectivity between the right caudate and motor cortex compared with healthy controls. blue/purple colors = decreased connectivity, yellow/red = increased connectivity; In AUD-HC map, yellow/red = AUD > HC. L= Left, R = Right. MNI coordinates were used.

To examine the relationship between behavioral ratings and the functional connectivity patterns noted above, a correlation analysis was performed with the application of adjusted Bonferroni correction. There was one area shown to be significantly correlated with stress-induced anxiety in AUD patients, but not in healthy controls. This area includes the connectivity between the left DLPFC and DmPFC (r=−.44; Bonferroni corrected at p <0.05; Figure 5); greater stress-induced anxiety was associated with reduced connectivity between the DLPFC and DmPFC in AUD patients. There was no region correlated with alcohol craving ratings.

Figure 5.

Neural connectivity associated with stress-induced anxiety in AUD patients. During stress exposure, reduced connectivity between the left LPFC and dorsomedial PFC (r= −.44) was associated with greater in-scan, stress-induced anxiety (p <0.05, adjusted Bonferroni correction applied).

Discussion

The current study examined neural correlates and connectivity patterns underlying impulse control difficulties in abstinent AUD patients. We identified three correlates of IMPULSE in key regions of emotional modulation including hypoactive responses to stress in the VmPFC, left LPFC (including DLPFC), and right caudate using whole brain correlation analyses. When these correlates were used as seed regions, AUD patients showed differential connectivity patterns compared with healthy controls. Overall, AUD patients displayed decreased connectivity with brain regions involved in cognitive and emotional regulation, but increased connectivity with sensory and motor cortices. These findings highlight the importance of integrity of the neural circuit of emotion regulation as well as its functional connectivity with other brain regions underlying impulse control difficulties associated with alcoholism.

Neural Correlates of Impulse Control Difficulties

Hypoactive response to stress associated with impulse control problems has been found in two key regions (VmPFC, left LPFC) of emotion regulation (Urry, et al., 2006) and in one subcortical region (right caudate) that is typically associated with reward-related habitual behaviors (Balleine, et al., 2007). The caudate is known to influence prefrontal decision making by processing motivational and habitual information (Balleine, et al., 2007), and increased caudate activity has been reported during stress response (Seo, et al., 2011). The VmPFC exerts regulatory control over the amygdala and striatum, allowing the flexible control of emotional response (Davidson, et al., 2000; Etkin, 2010; Urry, et al., 2006) and adaptive coping under stressful environments (Collins et al., 2014; Schiller & Delgado, 2010). The VmPFC and striatum closely interact with each other for reward-related reinforcement learning (Jocham, et al., 2011). Consistent with this, in AUD patients, altered VmPFC and striatal activity has been associated with high alcohol craving during stress and alcohol cue, with hypoactive VmPFC response to stress being additionally predictive of relapse severity following treatment (Seo, et al., 2013). The left LPFC has been associated with cognitive and inhibitory control (Asplund, et al., 2010; MacDonald, et al., 2000) and interacts with the VmPFC during emotional control by sending appropriate regulatory signals (Etkin, 2010). Taken together, stress- related hypoactivity in these regions associated with impulse control problems suggests that the neural circuit of reward learning and emotional modulation may be impaired in response to stress in AUD patients, which could lead to altered reward seeking and impulsive behaviors.

Of note, we did not observe significant associations between these regions and IMPULSE scores in healthy individuals. However, there were no group differences in correlation maps; at an uncorrected level, HC had similar patterns of correlations, but this effect was small and did not reach significance. In task activity maps, HC showed increased response to stress specifically in the VmPFC as compared with AUD patients. Given the relationship between hypoactive response to stress and IMPULSE, it appears that this increased, functional response in HC may account for their resiliency in regulating impulsivity and adaptive coping under stress. The role of the VmPFC in adaptive coping has been noted in prior literature (Collins et al., 2014), suggesting that hypoactive VmPFC response associated with IMPULSE may be related to a compromised coping ability under emotional distress in AUD patients, driving habitual and impulsive behaviors as a means of malapdaptive stress coping.

Altered Connectivity underlying Impulse Control Problems

Given the significance of these correlates (VmPFC, LPFC, caudate) in guiding emotion and motor-related behaviors in neuroscience literature, we further examined the integrity of network connectivity between these correlates with other brain regions. As expected, AUD patients showed stress specific, altered patterns of functional connectivity relative to healthy controls.

When functional connectivity was examined with the VmPFC seed, AUD patients showed reduced connectivity with the rostral ACC. The ACC guides emotional and social behaviors by monitoring conflicts and selecting appropriate targets for action (Botvinick, 2007). The VmPFC and ACC are anatomically and functionally connected with each other and play a crucial role in emotional regulation and conflict monitoring (Arnsten, 2009; Botvinick, 2007; Etkin, 2010). It has been shown that the VmPFC and ACC exert control over limbic-striatal regions for appropriate physiological and behavioral response to emotion (Davidson, et al., 2000; Etkin, 2010; Miller and Cohen, 2001). Accordingly, the decreased connectivity in the VmPFC-ACC in AUD patients may indicate inappropriate monitoring, dysfunctional coordinated control and interactions between these two regions. In response to stress, this may lead to impulsivity and behavioral dysregulation due to disinhibited emotional and limbic reactivity. With the right caudate seed, AUD patients showed increased connectivity between the right caudate and motor cortex relative to controls. The striatum has been closely connected to the motor cortex and guides motor control and implementation (Montgomery and Buchholz, 1991). Thus, increased connectivity between the right caudate and motor cortex may reflect more likelihood of disinhibited and habitually-driven motor behaviors under stress in AUD patients.

When the left LPFC, a key region of cognitive control, was used as a seed, AUD patients showed decreased connectivity with the dorsomedial PFC (DmPFC), but increased connectivity with sensory and motor cortices (pre-/post- central gyrus and middle occipital lobe) relative to healthy controls. The DmPFC has been associated with high level of cognitive operations, modulation, and adjustment of response strategies (Matsuzaka, et al., 2012). The DmPFC has also been associated with strategic reasoning and controlling heuristic learning in monkeys (Seo, et al., 2014). Thus, the decreased connectivity between the left LPFC and DmPFC suggest reduced cognitive modulation of emotion and an inability to develop coping strategies in response to stress, which may lead to stress-related emotional difficulties.

Consistent with this, decreased connectivity strength between the left LPFC and DmPFC was associated with increased in-scan anxiety response during stress in AUD patients. The left LPFC plays a role in executive control and conscious regulation of emotion, whereas the DmPFC is involved in evaluation and cognitive awareness of affect including negative and anxious emotion (for a review (Etkin, 2010)). A prior study also reports that hypo-reactivity to stress in the DmPFC is associated with anxiety response (Kalisch, et al., 2004). Along with these studies, our findings further suggest that decreased connectivity between the left DLPFC and DmPFC could contribute to greater subjective anxiety response during stress, probably due to reduced interaction between an executive control region (LPFC) and the DmPFC, a region that modulates stress-related emotional awareness.

The left DLPFC is also densely connected with sensory and motor cortices, as it integrates sensory/motor information received from these regions for appropriate cognitive control (Miller and Cohen, 2001; Selemon and Goldman-Rakic, 1988). Thus, increased connectivity between the left DLPFC and sensory and motor cortices suggests that AUD patients may be more prone to emotional and motor-driven behaviors due to excessive sensory and motor processing under stress.

It should be noted that group differences in the left DLPFC connectivity with the DmPFC and sensory/motor cortices remained present even when co-varied with smoking status, suggesting that this effect could be specific to alcoholism. There is high comorbidity between alcohol and tobacco use in the general population, which sharply increases with the presence of AUD; tobacco use in AUD individuals is approximately 50–60% according to the 2001–2002 National Epidemiology Survey (Falk, et al., 2006). Thus, altered connectivity in the VmPFC and caudate appears to account for impulse problems in all AUDs including those who smoke, whereas the left DLPFC connectivity is more specific to AUD alone. Consistent with this, relationships between the VmPFC and striatum and impulsivity have also been observed in smokers (Wilson et al., 2013) and other substance use disorders (Seo et al., 2008). To clarify the unique association between the left DLPFC connectivity and impulse control problems in alcoholism, future studies should systematically examine differential connectivity patterns in individuals with AUD and other substance use disorders. Taken together, our findings suggest that altered connectivity in AUD patients, marked by decreased connectivity with emotional and cognitive control regions but increased connectivity with sensory and motor processing regions, may underlie impulse control difficulties and emotion dysregulation in the context of stress.

During the task, AUD individuals showed hypoactive response during both stress and alcohol cue conditions in the medial PFC, insula, ACC/PCC, precuneus, and temporal lobe compared with controls. This finding is consistent with prior studies that have shown compromised neural circuits of stress and reward processing in later stages of alcohol addiction (Breese, et al., 2011; Koob, 2009). In addition, substantial overlap between stress and reward (e.g., alcohol-cue) circuits has been reported in addicted individuals including AUD patients (Seo, et al., 2013; Sinha and Li, 2007). However, we did not find associations between alcohol-cue provocation and IMPULSE scores, suggesting that individual differences in IMPULSE may be more influenced by the stress system. Although AUD individuals showed hypoactive responses to stress and alcohol cue conditions compared to controls, those with greater impulse problems within the AUD group may be more sensitive to stress-related hypoactivity. To clarify the underlying mechanisms, future studies would benefit from multimodal neuroimaging methods such as combined fMRI and positron emission tomography (PET), as fMRI alone only shows changes in blood flow in brain regions and does not provide neurochemical information within the circuit. It is likely that underlying biochemical response could further explain exact neuronal processes associated with stress-related impulse control difficulties in alcoholism.

In summary, under high-intense distress state, stress-related emotion and arousal can lead to reduced executive control and increased impulsive behaviors. Our study suggests that in AUD patients, impulse control difficulties during stress may be characterized by hypoactivity in key regions of emotion and reward modulaton (VmPFC, left LPFC, caudate) and their altered connectivity with other brain areas (decreased connectivity with control region, but increased connectivity with sensory and motor regions). These patterns may drive habitual and disinhibited behaviors under stress, thereby increasing vulnerability to alcohol use in AUD patients. Our findings highlight the importance of stress-related impulse control and maintaining the integrity of related neural connectivity in individuals with alcoholism. Under greater demand for control (e.g., emotional distress), AUD patients may be more vulnerable to impulsive and addictive behaviors by being unable to mobilize brain resources for coordinated actions.

The current study has important clinical implications. Impulse control problems in AUD patients may be more clearly manifested under high stress or emotionally challenging situations. In AUD patients, this may significantly influence their ability to control alcohol urges and other emotional behaviors during stress. Accordingly, our findings suggest that treatment approaches that focus on the recovery of stress-related, emotion regulatory regions and associated connectivity, along with combined stress and impulsivity management, could be beneficial in addressing impulse control problems in AUD patients. Future studies are needed to further investigate neural connectivity patterns underlying stress-related impulsivity and associated alcohol-related problems in individuals with alcoholism. In addition, future studies may also benefit from clinical investigations on whether chronically stressed individuals may be more vulnerable to alcohol related impulsive behaviors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from National Institute of Health (R01-AA013892-10; R01–AA20504-03; UL1–DE19856; PL1-DA024859; K08-AA023545-01).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any financial or other interest or relationship that might be perceived to influence the results or interpretation of the manuscript.

References

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:410–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asplund CL, Todd JJ, Snyder AP, Marois R. A central role for the lateral prefrontal cortex in goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:507–12. doi: 10.1038/nn.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balleine BW, Delgado MR, Hikosaka O. The role of the dorsal striatum in reward and decision-making. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8161–5. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1554-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A, Damasio H. Decision-making and addiction (part I): impaired activation of somatic states in substance dependent individuals when pondering decisions with negative future consequences. Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:1675–89. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM. Conflict monitoring and decision making: reconciling two perspectives on anterior cingulate function. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2007;7:356–66. doi: 10.3758/cabn.7.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Sinha R, Heilig M. Chronic alcohol neuroadaptation and stress contribute to susceptibility for alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:149–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Price JL. Limbic connections of the orbital and medial prefrontal cortex in macaque monkeys. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1995;363:615–641. doi: 10.1002/cne.903630408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen EH, Dixon WJ. Estimates of Parameters of a Censored Regression Sample. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1972;67:664–671. [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–73. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock RC, James GA, Holtzheimer PE, 3rd, Hu XP, Mayberg HS. A whole brain fMRI atlas generated via spatially constrained spectral clustering. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33:1914–28. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Dzemidzic M, Eiler WJ, Coskunpinar A, Karyadi K, Kareken DA. Negative urgency and ventromedial prefrontal cortex responses to alcohol cues: FMRI evidence of emotion-based impulsivity. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38:409–17. doi: 10.1111/acer.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation--a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WJ. Simplified Estimation from Censored Normal Samples. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1960;31:385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS, Papademetris X, Yang J, Jackowski M, Zeng X, Staib LH. Geometric strategies for neuroanatomic analysis from MRI. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A. Functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: a neural circuit perspective. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2010;2:251–77. doi: 10.1007/7854_2009_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:162–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn ES, Shen X, Scheinost D, Rosenberg MD, Huang J, Chun MM, Papademetris X, Constable RT. Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1664–71. doi: 10.1038/nn.4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Janet B. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version. New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal P, Sleeper J, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2007;89:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Peihua G, Rajita S. Interactive effects of cumulative stress and impulsivity on alcohol consumption. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:1376–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive behaviors. 2008;33:388–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Williams S, Howard R, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Movement-related effects in fMRI time-series. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:346–55. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CJ, Hoge R, Collins L, Woods R, Toga AW, Evans AC. Enhancement of MR images using registration for signal averaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:324–33. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jocham G, Klein TA, Ullsperger M. Dopamine-mediated reinforcement learning signals in the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex underlie value-based choices. J Neurosci. 2011;31:1606–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3904-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R, Salome N, Platzer S, Wigger A, Czisch M, Sommer W, Singewald N, Heilig M, Berthele A, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, Auer DP. High trait anxiety and hyporeactivity to stress of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex: a combined phMRI and Fos study in rats. Neuroimage. 2004;23:382–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hamann S. Neural correlates of positive and negative emotion regulation. Journal of cognitive neuroscience. 2007;19:776–98. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob. Dynamics of neuronal circuits in addiction: reward, antireward, and emotional memory. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2009;42(Suppl 1):S32–41. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1216356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Steinley D. Developmental trajectories of impulsivity and their association with alcohol use and related outcomes during emerging and young adulthood I. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:1409–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald AW, 3rd, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS. Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000;288:1835–8. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka Y, Akiyama T, Tanji J, Mushiake H. Neuronal activity in the primate dorsomedial prefrontal cortex contributes to strategic selection of response tactics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:4633–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119971109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EK, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:167–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery EB, Jr, Buchholz SR. The striatum and motor cortex in motor initiation and execution. Brain research. 1991;549:222–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90461-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolfe E. XMedCon- An open-source medical image conversion toolkit. European journal of nuclear medicine. 2003;30(Supp2) [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, de Wit H. Control yourself: alcohol and impulsivity. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2010;34:1303–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, Vogel AC, Laumann TO, Miezin FM, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:665–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AK, Jones A, Clarke N, Christiansen P. Alcohol-induced risk taking on the BART mediates alcohol priming. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:2273–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3377-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selemon LD, Goldman-Rakic PS. Common cortical and subcortical targets of the dorsolateral prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices in the rhesus monkey: evidence for a distributed neural network subserving spatially guided behavior. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4049–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04049.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Jia Z, Lacadie CM, Tsou KA, Bergquist K, Sinha R. Sex differences in neural responses to stress and alcohol context cues. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hbm.21165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Lacadie CM, Tuit K, Hong KI, Constable RT, Sinha R. Disrupted Ventromedial Prefrontal Function, Alcohol Craving, and Subsequent Relapse Risk. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:727–39. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Patrick CJ, Kennealy PJ. Role of Serotonin and Dopamine System Interactions in the Neurobiology of Impulsive Aggression and its Comorbidity with other Clinical Disorders. Aggression and violent behavior. 2008;13:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Sinha R. Neural mechanisms of Stress and Addiction. In: Adinoff B, Stein EA, editors. Neuroimaging in the Addictions. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, PO19 8SQ, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2011. pp. 211–233. [Google Scholar]

- Seo H, Cai X, Donahue CH, Lee D. Neural correlates of strategic reasoning during competitive games. Science. 2014;346:340–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1256254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1141:105–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addict Biol. 2009;14:84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z, Siedlarz KM. Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1198–208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KI, Hansen J, Tuit K, Kreek MJ. Effects of Adrenal Sensitivity, Stress- and Cue-Induced Craving, and Anxiety on Subsequent Alcohol Relapse and Treatment Outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, Li CS. Imaging stress- and cue-induced drug and alcohol craving: association with relapse and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:25–31. doi: 10.1080/09595230601036960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojek M, Fischer S. Impulsivity and motivations to consume alcohol: a prospective study on risk of dependence in young adult women. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2013;37:292–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urry HL, van Reekum CM, Johnstone T, Kalin NH, Thurow ME, Schaefer HS, Jackson CA, Frye CJ, Greischar LL, Alexander AL, Davidson RJ. Amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex are inversely coupled during regulation of negative affect and predict the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion among older adults. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4415–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3215-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J, Gao J-H, Lancaster J, PTF Clustered pixels analysis for functional MRI activation studies of the human brain. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.