Abstract

Purpose

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) accompanies the risk of bleeding and need for transfusion. There are several methods to reduce postoperative blood loss and blood transfusion. One such method is using tranexamic acid during TKA. The purpose of this study was to confirm whether tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA.

Materials and Methods

A total of 100 TKA patients were included in the study. The tranexamic acid group consisted of 50 patients who received an intravenous injection of tranexamic acid. The control included 50 patients who received a placebo injection. The amounts of drainage, postoperative hemoglobin, and transfusion were compared between the groups.

Results

The mean amount of drainage was lower in the tranexamic acid group (580.6±355.0 mL) than the control group (886.0±375.5 mL). There was a reduction in the transfusion rate in the tranexamic acid group (48%) compared with the control group (64%). The hemoglobin level was higher in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group at 24 hours postoperatively. The mean units of transfusion were smaller in the tranexamic acid group (0.76 units) than in the control group (1.28 units).

Conclusions

Our data suggest that intravenous injection of tranexamic acid decreases the total blood loss and transfusion after TKA.

Keywords: Knee, Arthroplasty, Transexamic acid, Blood loss, Transfusion

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is one of the most successful orthopedic surgeries in relieving pain and restoring joint function in end-stage osteoarthritis, either degenerative or secondary to inflammatory arthritis, trauma, tumors, or infection around the knee joint1,2,3,4,5). However, the surgery is accompanied by an unavoidable risk of bleeding and subsequent requirement of blood transfusion1,2,3). Transfusion of blood products is not a benign procedure and is associated with many possible risks such as infection, acute systemic reactions, and death4). Transfusions also lengthen rehabilitation time and hospital stay and increase the cost for the patient5,6). Therefore, blood loss control during and after surgery is an important consideration to achieve good results after TKA. Methods to reduce postoperative blood loss and avoid allogeneic blood transfusions include autologous blood transfusion, hypotensive anesthesia7), use of fibrin tissue adhesive8), drain clamping9,10,11,12), and administration of tranexamic acid13,14,15). Tranexamic acid administration during TKA surgery is one of most studied method. Studies have reported tranexamic acid reduced blood loss and the amount of blood needed in transfusions13,16). The administration of tranexamic acid also reportedly reduces the decrease in hemoglobin levels after TKA17). A meta-analysis of 12 studies concluded intravenous tranexamic acid injections reduced blood transfusion and blood loss in TKA and total hip arthroplasty (THA) without increasing the risk of thromboembolic complications18). Another meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials concluded the use of tranexamic acid for patients undergoing TKA reduced the requirement of blood transfusion19). In these studies, however, the blood loss was measured as the loss during surgery plus the drainage volume. Since there may also have been hidden losses as a result of hemolysis and tissue extravasation, which would not have shown on drain output, the true effect of tranexamic acid on blood loss was not clear20). A true estimate of total blood loss can be more appropriately made using a hemoglobin balance method20,21). The calculated blood loss based on hemoglobin drop and body volume takes into consideration both the hidden and evident losses. The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of tranexamic acid on total blood losses including hidden and evident losses through hemoglobin balance method21). We hypothesized that tranexamic acid would decrease the total blood loss during TKA measured using a hemoglobin balance method21).

Materials and Methods

1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chonnam National University Bitgoeul Hospital. This prospective comparative study was conducted in a single institution based in two hospitals. All patients with primary end-stage knee osteoarthritis (Kellgren-Lawrence grades, 3–4) awaiting surgery were eligible for the study. We excluded patients with secondary osteoarthritis (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, posttraumatic osteoarthritis, gouty arthritis), a cardiovascular problem (e.g., myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, angina, heart failure), simultaneous bilateral TKA, a history of thromboembolic disease, bleeding disorder, known allergy to tranexamic acid, and lifelong warfarin therapy for thromboembolism prophylaxis. A total of 100 patients were evaluated during the study period. Patients undergoing TKA were prospectively divided into one of the two study groups using sealed, opaque envelopes that were opened immediately before surgery.

2. Methods of Tranexamic Acid and Outcome Assessment

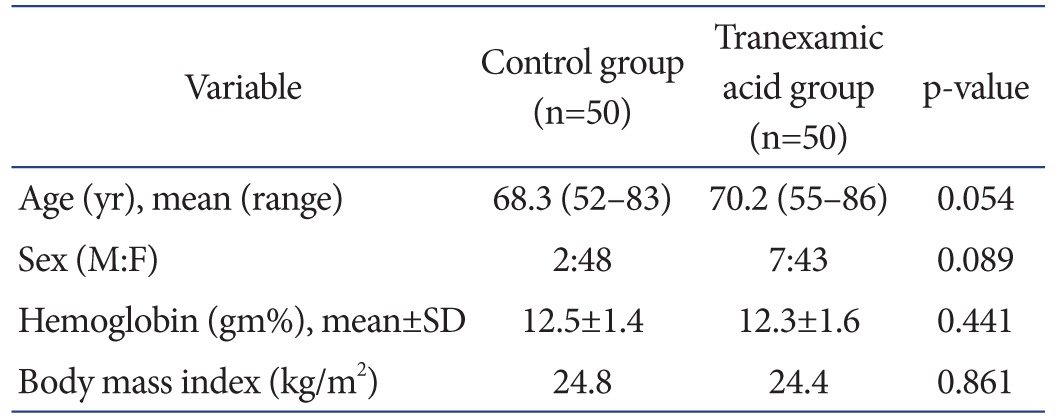

In the tranexamic acid group, patients received tranexamic acid intravenously (10 mg/kg) 10 minutes before tourniquet deflation and again at 3 hours postoperatively22,23). This regime was based on successful outcomes in literature and our own experience. In the control group, patients received a placebo 5 mL 0.9% normal saline at the similar timings of the tranexamic acid group. Preoperative data included age at the time of the operation, gender, and preoperative hemoglobin level. There were no differences between groups regarding the preoperative data (Table 1). Hemoglobin levels were measured 2 weeks preoperatively and 6 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours, and 5 days postoperatively. Total losses were calculated based on a 'hemoglobin balance method' described in literature21). This method estimates the blood volume of a patient based on the postoperative hemoglobin drop. The lowest value of the postoperative hemoglobin level obtained until the 5th postoperative day was used to calculate the hemoglobin drop. Transfusions were performed in compliance with our hospital policy. Blood transfusions were planned for asymptomatic patients with a hemoglobin level of <8.0 gm%. Transfusions were undertaken for patients with a level of <10.0 gm% only if they had 1) symptoms that were not well tolerated, were related to anemia, and could not be attributed to another cause (myocardial ischemia or hypoxemia) or 2) ongoing blood loss24).

Table 1. Demographic Details of Patients in Both Groups.

SD: standard deviation.

3. Surgical Technique

All operations were performed or supervised by two surgeons (EKS and JKS) using a midline skin incision and medial parapatellar arthrotomy. A posterior-stabilized type implant was used and the patella was not resurfaced in all cases. All patients received general or spinal anesthesia depending on the discretion of the anesthesiologist. A dose of 1 g cetrazole was given intravenously shortly before the operation. A tourniquet was applied around the upper thigh after elevation of the limb and exsanguination with an Esmarch bandage and inflated to a pressure of 280 mmHg before skin incision. An intramedullary alignment rod was used for femoral cutting and an extramedullary guide system was used for tibial cutting. Meticulous electric cauterization of the soft tissue bleeding points was performed throughout the surgery. The tourniquet was not released until skin closure and application of a compressive dressing. Intraoperative blood loss was negligible in all patients because the tourniquet was not deflated until wound closure. In each knee, one intra-articular drain was applied and connected to a high-vacuum drain bottle. The patients were asked to utilize an intermittent sequential pneumatic compression device for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis as soon as possible. The compressive dressing and Foley catheter were removed on the first day after surgery. The drains were emptied every day and the amount of drained blood was measured. The drains were removed only when this amount was less than 100 mL for 24 hours. On average, drains were kept for 3 days (range, 2 to 5 days). This has been our institution's policy, as we have observed that removal of drains at one preselected time may not work in all cases. Some cases have collection for longer periods and early removal in such cases may not only cause erroneous lower recordings of drained blood but also has a risk of hematoma formation. Both groups followed a standard postoperative rehabilitation protocol, including continuous passive motion of the knee and muscle strengthening exercises on the first day after surgery. All patients were asked to get out of bed with walker support on the afternoon of the first postoperative day to decrease the incidence of DVT, as described by Pearse et al.25). Mechanical DVT prophylaxis using a pneumatic compression device was performed in all patients. Considering the low incidence of DVT in Asian populations26), routine use of pharmacological prophylaxis was not prescribed according to our institutional policy. Routine screening for DVT was not done for asymptomatic patients. Symptomatic patients with excessive calf swelling and pain were screened for DVT using Doppler ultrasonography and computed tomography angiography. All patients at discharge were explained about warning symptoms of infection and DVT and were asked to report immediately to the emergency department in case of development of such symptoms.

4. Data Evaluation

The total volume of drained blood and the decrease in hemoglobin at 6 hours, 24 hours, 48 hours and 5 days postoperatively were recorded. Blood transfusions were recorded as the number of units of packed erythrocytes. All patients were discharged from the hospital after two weeks of surgery. All quantitative data were expressed as mean±standard deviation. Statistical significance of differences in the mean values of continuous variables such as age, preoperative hemoglobin, total volume of drained blood, and postoperative decrease in hemoglobin level were determined using Student t-test. Chi-square test was used for categorical data including the need for blood transfusion. SPSS ver. 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All aspects of the statistical analysis were reviewed by a statistician.

Results

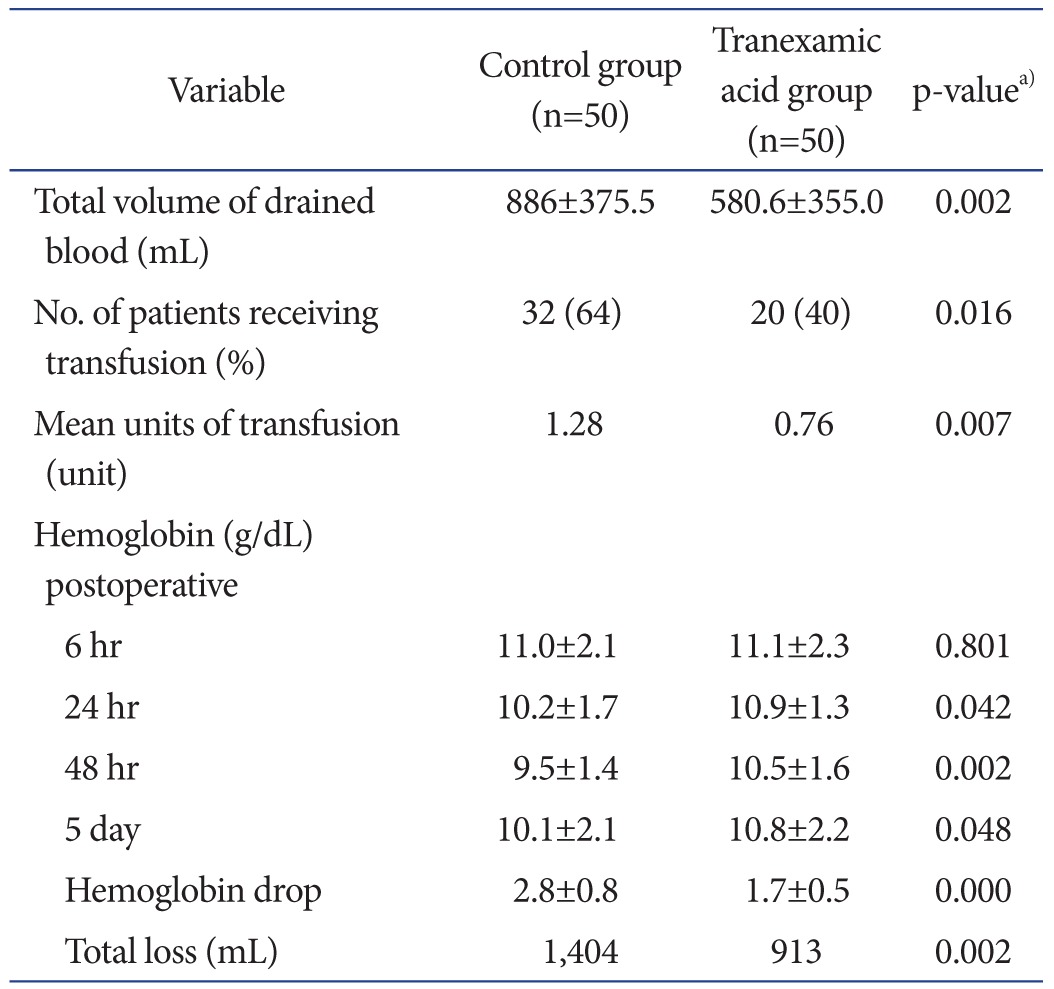

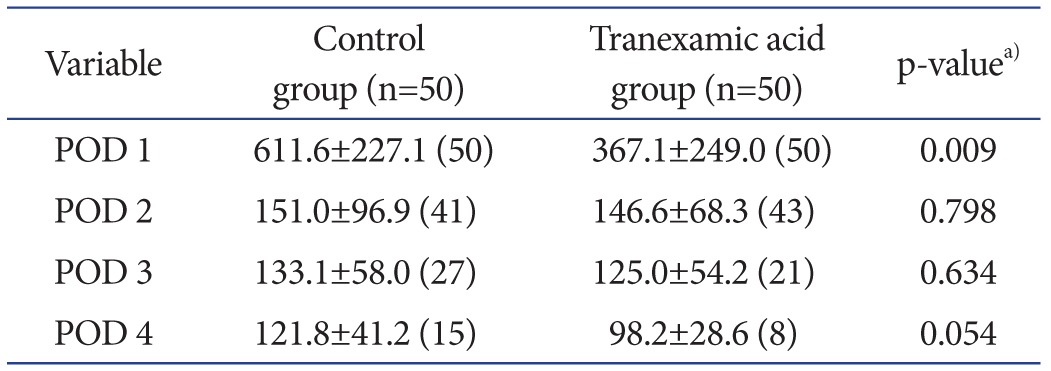

The mean postoperative total volume of drained blood was lower in the tranexamic acid group (580.6±355.0 mL) than in the control group (886.0±375.5 mL) (p=0.002). There was a reduction in the transfusion rate in the tranexamic acid group compared with the control group (40% vs. 64%; p=0.016). The mean units of transfusion were smaller (p=0.007) in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group (0.76 units vs. 1.28 units). The hemoglobin level at 6 hours postoperatively was similar (p=0.801) in the two groups, but it was greater in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group at 24 hours, 48 hours, and 5 days postoperatively at statistically significant levels (Table 2). The hemoglobin drop was calculated as the difference between the lowest postoperative hemoglobin level and the preoperative hemoglobin level. This drop was significantly high for the control group (2.8 gm/L) compared to the tranexamic acid group (1.7 gm/dL) (p=0.000). The total amount of blood loss calculated using the hemoglobin balance method21) was significantly less in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group (p=0.002) (Table 2). There were no cases of symptomatic DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in both groups during the 3 months of follow-up. Table 3 shows the amount of evident blood loss on each postoperative day measured based on the drain output and the number of patients still utilizing the drain. Postoperative day 1 losses were significantly different between the groups, but no difference was found on subsequent days.

Table 2. Postoperative Hemoglobin, Total Drain Output, and Blood Transfusion.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation.

a)p-values are for unpaired two-tailed Student t-test, except for blood transfusion which is for chi-square test.

Table 3. Postoperative Drain Output.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation (number).

POD: postoperative day.

a)p-values are for unpaired two-tailed Student t-test.

Discussion

The most important finding of the current study is that intravenous tranexamic acid decreased the perioperative blood loss, calculated total blood loss, hemoglobin drop, and need for transfusion. Furthermore, this method did not cause an increase in the incidence of thromboembolic events.

Surgical trauma after arthroplasty results in a hyperfibrinolytic state27). Since early postoperative bleeding is the result of a shift in the hemostatic mechanism towards fibrinolysis, the anti-fibrinolytic drugs such as tranexamic acid are very effective to control bleeding. We agree with most reports in literature describing the reduction in blood loss as ranging 30%–50% 13,14,15). Most of these reports have evaluated blood losses in drains at 24–48 hours after surgery. Similar to these results, we also observed a reduction of 40% in blood loss on postoperative day 1 (367 mL vs. 611 mL).

The difference in drain output between two groups was observed particularly on 1st postoperative day. This was primarily because tranexamic acid has a half-life of 3 hours and it remains in the extravascular tissue up to 17 hours28), after which it has no effect on postoperative bleeding. Therefore, postoperative bleeding after 1st postoperative day showed no significant difference between two groups. Despite this, the overall blood loss in the tranexamic acid group was 35% less than that in the control group. This was because most bleeding after arthroplasty tends to occur during the first 24 hours1,2,3,4,5).

We found that tranexamic acid was effective in decreasing not only the evident blood loss but also the total blood loss based on the calculation using the hemoglobin balance method. It is difficult to compare total losses in most studies, as there is no uniform criterion for measurement. Most studies have not calculated total losses22,23). Few studies have used hematocrit drop29,30) while others have used hemoglobin drop24). Some studies have taken 2nd postoperative day hemoglobin values31) while others have used 4th postoperative day values21) for calculation. We believe that hemoglobin usually decreases for initial 3–5 days after surgery and then begins to rise. The lowest value measured during this period best shows the true loss. Therefore, instead of a fixed day value, we used the lowest hemoglobin value for our calculation. We saw a reduction of 37% in total blood loss in the tranexamic acid group compared to the control group. Despite the utilization of different methods for calculation, most authors have shown tranexamic acid decreases total blood loss21,29,30).

We also observed a 24% decrease in the need for transfusion in the tranexamic acid group, and this reduction was statistically significant in consensus with data in literature. In addition, not only was the number of patients requiring transfusions less, the total number of transfusions required for each patient was significantly less in the tranexamic acid group compared to the control group. The rate of transfusions in our study was a little high in both groups probably because of the female predominance; females tend to have lower preoperative hemoglobin levels compared to those of males. In our study, the postoperative hemoglobin was between 8–10 gm% at the time of transfusion in most of the patients who were transfused (16 in tranexamic acid group and 24 in control group) due to tachycardia not responding to fluid management; however, transfusion trigger has mostly been less than 8 gm% in literature21,24).

Tranexamic acid creates a prothrombotic state by inhibiting fibrinolysis. This raises the concern of DVT. However, we observed no adverse effects of tranexamic acid in terms of the development of symptomatic DVT and PE. The safety of tranexamic acid has been well established in literature. Recent reviews and meta-analyses have found no increased risk of thromboembolic events. They found that perioperative intravenous tranexamic acid administration was not associated with increased risk of complications.

We recognize limitations to our study. First, the sample size (100 patients) was too small to address some questions. Second, the study design was not double-blinded, randomized and can only be regarded as a prospective comparative trial. Third, the operations were performed by only two (EKS and JKS) of the total authors of this study. Fourth, the female to male ratio in our study was high because most TKA patients in our country are females. Female patients may have lower preoperative hemoglobin levels and greater blood transfusion rates after TKA than males; however, the ratios of females to males and the preoperative hemoglobin levels were not different between the two groups in the study. Lastly, intraoperative anesthetic technique was determined based solely on the discretion of an anesthesiologist. This may have affected the total blood loss, and a study using a different anesthetic technique may be more appropriate. However, there was no statistically significant difference in the ratio of spinal to general anesthesia between the groups both groups, and thus we believe any effect the anesthetic technique could have on the results would have been the same in both groups.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our prospective comparative study showed that the preoperative and postoperative single injection of tranexamic acid could be effective in reducing total blood loss and the need for blood transfusion after TKA for patients without any history of thromboembolic disease.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Prasad N, Padmanabhan V, Mullaji A. Blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of risk factors. Int Orthop. 2007;31:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee S, Issa K, Kapadia BH, Khanuja HS, Harwin SF, McInerney VK, Mont MA. Intraoperative nonpharmacotherapeutic blood management strategies in total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2013;26:387–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1353993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cushner FD, Friedman RJ. Blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(269):98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell MJ, Wilson MJA. Complications of blood transfusion. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2006;6:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower WF, Jin L, Underwood MJ, Lam YH, Lai PB. Perioperative blood transfusion increases length of hospital stay and number of postoperative complications in non-cardiac surgical patients. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:482–495. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e08e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juelsgaard P, Larsen UT, Sorensen JV, Madsen F, Soballe K. Hypotensive epidural anesthesia in total knee replacement without tourniquet: reduced blood loss and transfusion. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:105–110. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2001.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang GJ, Hungerford DS, Savory CG, Rosenberg AG, Mont MA, Burks SG, Mayers SL, Spotnitz WD. Use of fibrin sealant to reduce bloody drainage and hemoglobin loss after total knee arthroplasty: a brief note on a randomized prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1503–1505. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad N, Padmanabhan V, Mullaji A. Comparison between two methods of drain clamping after total knee arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:381–384. doi: 10.1007/s00402-005-0813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen PC, Jou IM, Lin YT, Lai KA, Yang CY, Chern TC. Comparison between 4-hour clamping drainage and non-clamping drainage after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsumara N, Yoshiya S, Chin T, Shiba R, Kohso K, Doita M. A prospective comparison of clamping the drain or postoperative salvage of blood in reducing blood loss after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:49–53. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada K, Imaizumi T, Uemura M, Takada N, Kim Y. Comparison between 1-hour and 24-hour drain clamping using diluted epinephrine solution after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:458–462. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benoni G, Fredin H. Fibrinolytic inhibition with tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study of 86 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molloy DO, Archbold HA, Ogonda L, McConway J, Wilson RK, Beverland DE. Comparison of topical fibrin spray and tranexamic acid on blood loss after total knee replacement: a prospective, randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:306–309. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.17565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka N, Sakahashi H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:702–705. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.83b5.11745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benoni G, Carlsson A, Petersson C, Fredin H. Does tranexamic acid reduce blood loss in knee arthroplasty? Am J Knee Surg. 1995;8:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hynes M, Calder P, Scott G. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2003;10:375–377. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(03)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31:529–537. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0303100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cid J, Lozano M. Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic red cell transfusions in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty:results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion. 2005;45:1302–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehat KR, Evans R, Newman JH. How much blood is really lost in total knee arthroplasty?: correct blood loss management should take hidden loss into account. Knee. 2000;7:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0160(00)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JY, Chin PL, Moo IH, Pang HN, Tay DK, Chia SL, Lo NN, Yeo SJ. Intravenous versus intra-articular tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a double-blinded randomised controlled noninferiority trial. Knee. 2016;23:152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veien M, Sorensen JV, Madsen F, Juelsgaard P. Tranexamic acid given intraoperatively reduces blood loss after total knee replacement: a randomized, controlled study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:1206–1211. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2002.461007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camarasa MA, Olle G, Serra-Prat M, Martin A, Sanchez M, Ricos P, Perez A, Opisso L. Efficacy of aminocaproic, tranexamic acids in the control of bleeding during total knee replacement: a randomized clinical trial. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:576–582. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Perez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:1937–1944. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearse EO, Caldwell BF, Lockwood RJ, Hollard J. Early mobilisation after conventional knee replacement may reduce the risk of postoperative venous thromboembolism. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:316–322. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B3.18196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park YG, Ha CW, Lee SS, Shaikh AA, Park YB. Incidence and fate of "symptomatic" venous thromboembolism after knee arthroplasty without pharmacologic prophylaxis in an Asian population. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benoni G, Lethagen S, Fredin H. The effect of tranexamic acid on local and plasma fibrinolysis during total knee arthroplasty. Thromb Res. 1997;85:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol) 1980;14:41–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology. 1983;58:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198303000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma J, Huang Z, Shen B, Pei F. Blood management of staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty in a single hospitalization period. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:116. doi: 10.1186/s13018-014-0116-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]