Abstract

Some adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) believe that chromium-containing supplements will help control their disease, but the evidence is mixed. This narrative review examines the efficacy of chromium supplements for improving glycemic control as measured by decreases in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Using systematic search criteria, 20 randomized controlled trials of chromium supplementation in T2DM patients were identified. Clinically meaningful treatment goals were defined as an FPG of ≤7.2 mmol/dL, a decline in HbA1c to ≤7%, or a decrease of ≥0.5% in HbA1c. In only a few randomized controlled trials did FPG (5 of 20), HbA1c (3 of 14), or both (1 of 14) reach the treatment goals with chromium supplementation. HbA1c declined by ≥0.5% in 5 of 14 studies. On the basis of the low strength of existing evidence, chromium supplements have limited effectiveness, and there is little rationale to recommend their use for glycemic control in patients with existing T2DM. Future meta-analyses should include only high-quality studies with similar forms of chromium and comparable inclusion/exclusion criteria to provide scientifically sound recommendations for clinicians.

Keywords: chromium, fasting plasma glucose, hemoglobin A1c, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, 29.1 million Americans (or 9.3% of the population) were living with diabetes, and 1.7 million new cases of diabetes were diagnosed.1 Diabetes increases the risk for cardiovascular disease and neuropathy and is the leading cause of blindness in the United States. Overweight and obesity, risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), remain a serious public health problem. Clearly, primary and secondary prevention strategies to decrease the risk of diabetes and its complications are a public health imperative.

Trivalent chromium, or chromium 3, is found in foods and dietary supplements. Intakes from food among American adults range from 23 to 29 μg/d for women and from 39 to 54 μg/d for men, levels that meet or exceed the adequate intake of chromium established by the Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine.2

About half of American adults use dietary supplements, primarily because they believe supplements promote overall health and prevent disease.3 Many use chromium-containing supplements to reduce their risk of diabetes or to complement conventional medical therapies used in the management of diabetes.1 There are thousands of chromium-containing supplements on the market, many of which are purported to have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism. Since chromium potentiates the action of insulin, chromium supplements may lower blood sugar and improve glucose tolerance. Although chromium’s role as a cofactor for insulin action is not fully understood, it was once thought to be a constituent of the glucose tolerance factor, a water-soluble complex containing both chromium and niacin that may be needed for normal glucose tolerance. Chromodulin, a low-molecular-weight, chromium-binding compound, may play a role in mediating the intracellular effects of chromium.4 Because acute chromium deficiency can cause reversible insulin resistance and diabetes, chromium is routinely added to total parenteral nutrition solutions.5,6

In 2005 the US Food and Drug Administration permitted a qualified health claim indicating that the evidence for chromium picolinate supplements in reducing the risk of insulin resistance and, possibly, T2DM is highly uncertain.7 Data from clinical and observational studies since then have been mixed. Six recent meta-analyses evaluated randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of the effects of chromium supplementation on blood glucose in T2DM patients by measuring either fasting plasma glucose (FPG) or hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c]), or both. Slightly more than half of the trials found a statistically significant lowering of FPG (4 of 6), HbA1c (3 of 5), or both (3 of 5) measures. However, whether glycemic control improved to a clinically meaningful as well as statistically significant level was not addressed. To address the limitations of systematic reviews in nutrition and, in particular, for dietary supplements, a systematic search of RCTs in the literature was conducted, with the results presented here as a narrative review addressing whether chromium supplements are efficacious in improving glycemic control by lowering blood sugar, as measured by FPG and HbA1c. The evidence on whether different forms, doses, or durations of chromium supplementation differed in their effects is also examined.

DEFINING THE INCLUSION OF STUDIES IN THE DATA SET

A comprehensive PubMed literature search was performed for human studies published in English from January 1, 1994, through December 31, 2014, using the following search terms: chromium, blood glucose, blood sugar, glucose metabolism disorders or metabolic syndrome, and RCT or systematic review or meta-analysis. The inclusion criteria for trials with adults (>18 years) were as follows: T2DM defined by self-report, clinical diagnosis, or biochemically determined FPG or HbA1c; use of hypoglycemic agents with and without concurrent treatment; stable, chronic disease; and participation in a placebo- or comparator-controlled RCT with a dietary supplement for glycemic control. All RCTs in the published meta-analyses were included. Additional references were obtained from the period after the cited meta-analyses had been completed. Clinical trials and studies were excluded if they included the following: children only; study arms solely of patients with type 1 diabetes; patients with unstable chronic disease and/or acute conditions (eg, severe heart failure, hemodialysis, myocardial infarction); patients with HIV infection; and combination therapies without a separate chromium supplement arm. Unpublished, observational, nonrandomized, and unblinded studies were also excluded, as were all studies that did not report pre- and postintervention results.

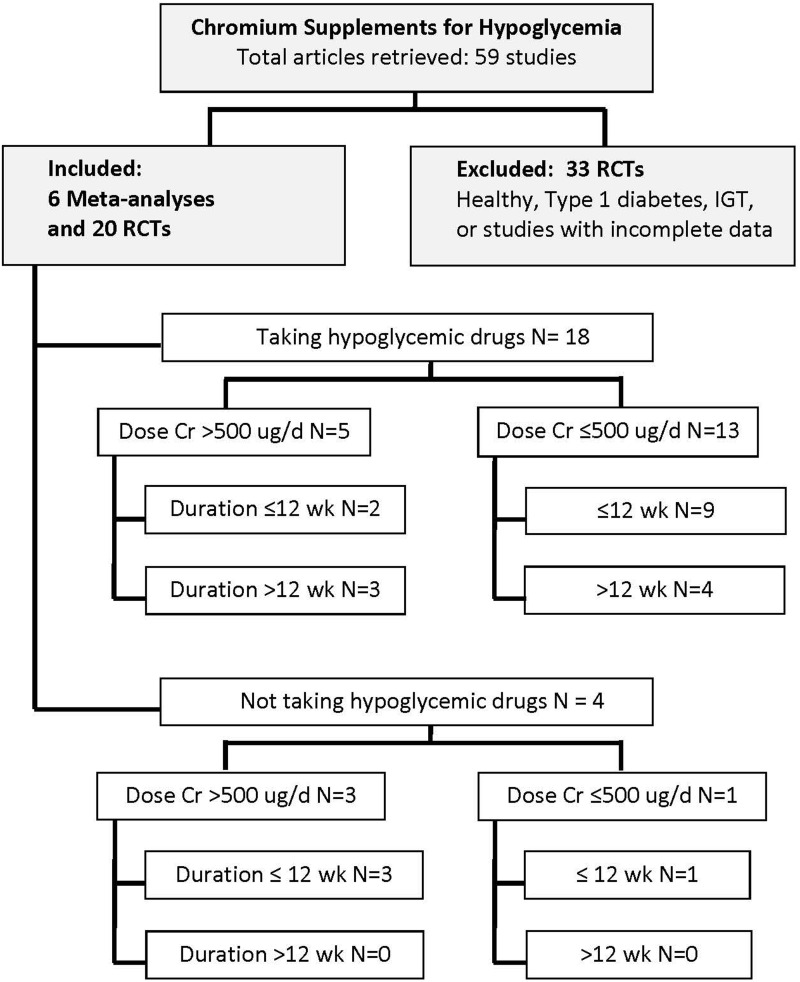

Figure 1 presents the search strategy and the number of studies retrieved meeting the inclusion criteria. Twenty RCTs of patients with T2DM met the inclusion criteria. A total of 33 RCTs were excluded for the reasons noted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Literature search strategy and additional review criteria for categorizing studies by dose and duration in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Abbreviations: Cr, chromium; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

All of the existing studies in the available meta-analyses and elsewhere, as well as one more recent RCT that conformed to the inclusion criteria and measured the effects of chromium supplements on FPG and HbA1c in T2DM patients, were reviewed and included. T2DM was defined as either an elevated FPG of >126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/L) or an HbA1c of >6.5%.8 Table 1 describes the inclusion criteria of the meta-analyses reviewed, and Table 2 presents the RCTs within these meta-analyses. It was not appropriate to perform a new meta-analysis of the effects of chromium supplements on patients with T2DM because of the significant heterogeneity between the studies, described in detail below. A narrative review was performed by summarizing the mean values for the chromium supplement and placebo arms in patients with T2DM at baseline and post supplementation.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria and study characteristics of 6 meta-analyses and the current review

| Meta-analyses |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Althuis et al. (2002)9 | Balk et al. (2007)10 | Patal et al. (2010)11 | Abdollahi et al. (2013)12 | Bailey (2014)13 | Suksomboon et al. (2014)14 | Current narrative review | |

| Population | Healthy adults, IGT,T2DM | T1DM, T2DM, IGT as defined by WHO or ADA standards | T2DM | T2DM | Healthy nonpregnant adults with and without diabetes (diabetes class not defined) | T1DM, T2DM. | T2DM |

| Inclusion criteria | Controlled clinical trials in subjects randomly assigned to chromium supplementation or a control, either placebo or active. All languages | RCTs of chromium supplements, regardless of formulation | RCTs in adults >19 y with HbA1c >7%. Chromium picolinate studies only. English language | RCTs with chromium supplementation >250 μg for >3 mo. Included studies with chromium + biotin | Placebo-controlled RCTs for which effect size could be calculated. English language | RCTs comparing chromium (mono or combined) supplementation against placebo. FPG measured >3 wk, HbA1c >8 wk. No language restriction | RCTs with FPG or HbA1c measures and chromium as single-ingredient supplement. English language |

| Exclusion criteria | Nonrandomized trials | Studies of <3 wk and <10 participants, as well as abstracts, letters, and conference proceedings | Studies <3 mo duration | Duplicated articles and papers. Low Jadad quality score | Chromium in combination with other nutrients; insufficient data for statistical analysis | Low Jadad quality score (<3) | Healthy subjects, IGT, T1DM |

| Databases and search years | MEDLINE and Cochrane Library, 1966 to May 2000; Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, April 2000 | MEDLINE and CAB database through August 2006 | MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and HERDIN; 1980–2008 | PubMed, Scopus, Scirus, Google Scholar, and IranMedex; 2000–2012 | MEDLINE and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register through February 2013 | MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Web of Science, until May 2013 | PubMed, January 1991 to 2014 |

| No. of studies in meta-analysis | 15 | 38 | 6 | 7 | 16 | 25 | 20 |

Abbreviations: ADA, American Diabetes Association; CAB, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau; Cr, chromium; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; RCT, randomized clinical trial; T1DM, type 1 diabetes mellitus; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WHO, World Health Organization.

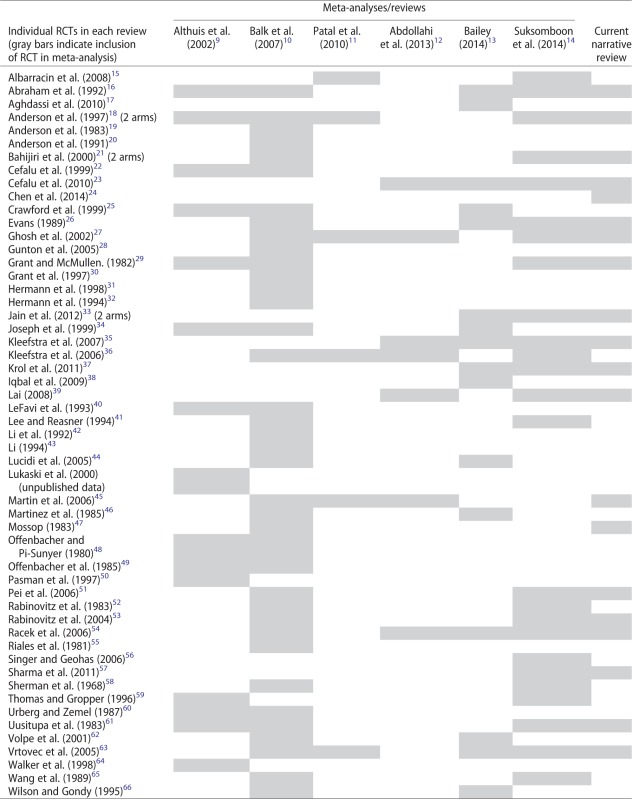

Table 2.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in each of the 7 reviews on chromium supplementation and glycemic control

|

Synthesizing the results of the data set

Twenty RCTs (22 study arms) of patients with T2DM, including all in the existing meta-analyses and the one additional RCT24 that had been completed after the last meta-analysis, are summarized in this report. A few studies controlled for or monitored background diets and physical activity levels, though most did not. Study intervention periods varied from 3 weeks to 6 months. Exposures were difficult to estimate. Not only did elemental chromium doses range from 1.28 to 1000 μg, but dosing schedules also varied and sometimes were not provided, and baseline intakes of chromium were often not reported. The type of chromium supplement used also varied. Seven different formula preparations were used, some of which were not well described. Chromium picolinate products were used most frequently, followed by chromium-containing yeast formulations, such as brewer’s yeast and chromium chloride. Often the doses were listed as yeast with a stated chromium content; at other times, the doses were stated simply as the amount of chromium in the yeast or as chromium chloride or chromium picolinate. In addition, the quality of the studies that were included varied with respect to making causal inferences. Of the designs for analysis used in the 20 RCTs, only 11 of 20 (55%) had the stronger intent-to-treat analysis (ITT) design in which all patients randomized were assessed and included in means at the end of the study; the remaining 9 studies used a weaker per-protocol analysis, which analyzed only study completers, so that the means for outcomes did not include dropouts and thus may have been biased.

Studies measuring HbA1c

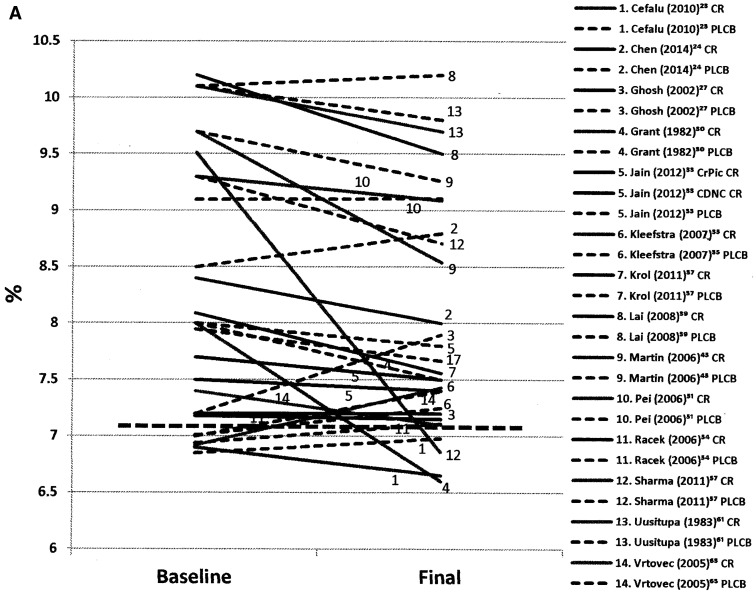

Figure 2A displays mean changes in HbA1c, from baseline to post supplementation, in subjects enrolled in the chromium supplementation and placebo arms of the RCTs. Mean baseline HbA1c levels differed from study to study, although all were above the levels indicative of diabetes (HbA1c >6.5%) at baseline. There was a lack of a consistent decrease with chromium supplementation in HbA1c values in the 14 studies. Chromium supplementation also did not bring HbA1c levels to those recommended in treatment guidelines (eg, ≤7.0%). Note also that 10 of 14 studies enrolled subjects who had been prescribed lifestyle modifications and were taking hypoglycemic agents and apparently continued taking them during the supplementation period. Only two means were at or below the upper end of the treatment goal range after chromium supplementation, but in several studies the means declined to a lesser degree.

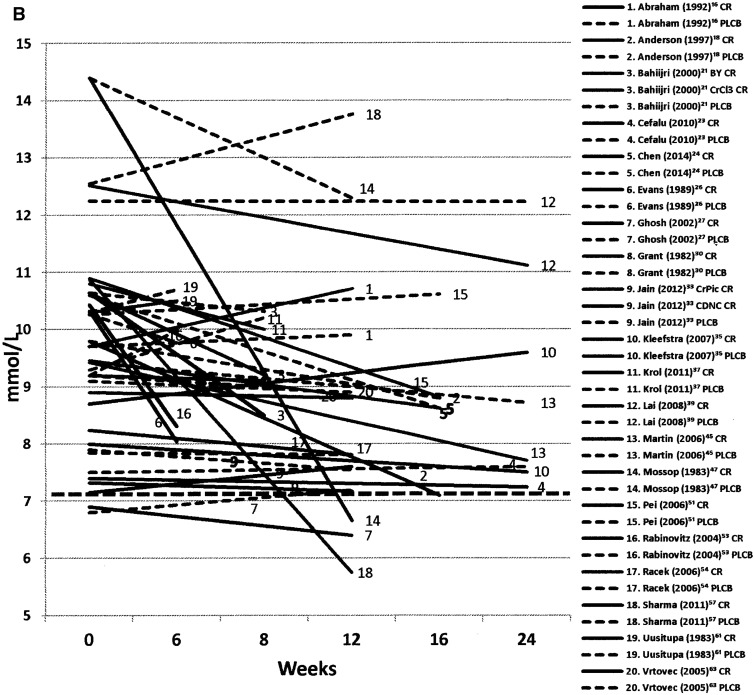

Figure 2.

(A) Mean changes in HbA1c from baseline to postchromium supplementation for 14 studies and placebo arms. Solid line is chromium treatment, dashed line is placebo control, and heavy dotted line represents HbA1c treatment goal of ≤7.0%.8 (B) Mean changes in HbA1c by length of study, from pre- to postchromium supplementation, for 14 studies and placebo arms. Solid line is chromium treatment, dashed line is placebo control, and heavy dotted line represents HbA1c treatment goal of ≤7.0%.8 Abbreviations: CDNC, chromium dinicocysteinate; CR, chromium, CrPic, chromium picolinate; PLCB, placebo.

Figure 2B shows the mean changes in HbA1c by length of study for subjects enrolled in the chromium supplementation and placebo arms. Initially, it was hypothesized that, if the effects of chromium on metabolism took many weeks or months to manifest, the duration of supplementation might be important. Since the length of the studies varied considerably, from less than a month to 6 months, the longer studies might be more likely to show effects. Such a phenomenon might be particularly evident for HbA1c measures, since red blood cells have a lifespan of 120 days, and the glycosylated hemoglobin might build up over a longer period. HbA1c values reflect fluctuations in blood glucose levels over many weeks or months, and therefore they are regarded as a more stable measure than FPG, which varies from hour to hour and day to day. Duration of the supplementation did not seem to markedly affect the size of the decline, nor were trends between dose and form of the supplement evident. HbA1c at baseline differed little between the supplemented and placebo groups, as most were also receiving hypoglycemic medications.

Again, emphasis was placed on studies in which mean HbA1c levels dropped considerably to ascertain if any common elements that might be associated with the positive effects observed could be identified. The only study of patients not taking hypoglycemic medications concurrently with the chromium supplement was the trial of Sharma et al.,57 in which 20 individuals with new-onset T2DM were given a brewer’s yeast supplement (42 μg of chromium per day) for 12 weeks in a single-blind RCT using an ITT analysis in India. The mean HbA1c of 9.5% at baseline fell to 6.9%, reaching the treatment goal range after supplementation. However, there was considerable variability in response, as evident in the large coefficient of variation.

All of the other studies in which HbA1c dropped considerably were conducted in patients who were receiving hypoglycemic medications along with the chromium supplement. Grant and McMullen’s29 study of 37 T2DM patients on hypoglycemic agents tested a brewer’s yeast supplement (1.28 μg of chromium per day) for 7 weeks using a crossover design and an ITT analysis. The mean HbA1c of 8.0% at baseline fell to 6.6%, reaching the treatment goal range by the end of the supplementation period.

The Lai trial,39 conducted in Taiwan, used a chromium dosage of 1000 μg/d from supplemented yeast (it was unclear what form of yeast was used) in a 6-month RCT with an ITT analysis in 10 T2DM patients with a baseline FPG of >8.5 mmol/L and HbA1c levels of >8.5%. The intervention was associated with a drop in HbA1c from 10.2% to 9.5%, which was above the treatment goal.

Krol et al.37 also used brewers’ yeast (500 μg/d) in an 8-week study testing the effects of the supplement in 28 T2DM Polish patients receiving hypoglycemic medications in a crossover study design. Baseline HbA1C levels of 8.1% fell to 7.6% in the 20 patients included in the per-protocol analysis. However, 8 subjects were dropped from the analysis, 4 from each group.

The 2 other studies that showed some, but lesser, lowering of HbA1C with a chromium supplement used chromium picolinate. Rabinovitz et al.53 studied 39 T2DM patients in the treatment arm who were 61 to 83 years of age and receiving hypoglycemic medications, including both sulfonylureas and insulin, and who were provided with supplemental chromium picolinate (400 μg/d) for 3 weeks. The study was an ITT analysis. Baseline HbA1c levels were 8.2%, and these fell to 7.6 % post treatment; however, mean standard deviations or mean standard errors were not reported, nor were final HbA1c values reported in the control group, precluding statistical analysis. Martin et al.45 enrolled 17 T2DM patients whose FPG values were >125 mg/dL and <170 mg/dL at baseline and who were also taking hypoglycemic medications (sulfonylureas). Patients received chromium picolinate 1000 μg/d for 24 weeks in a double-blind RCT using a per-protocol analysis. Only 14 of the 17 patients completed the study, and the mean HbA1c of the completers declined from 9.7% to 8.5% with the chromium supplement, although HbA1c levels remained above treatment goals.

Studies measuring fasting plasma glucose

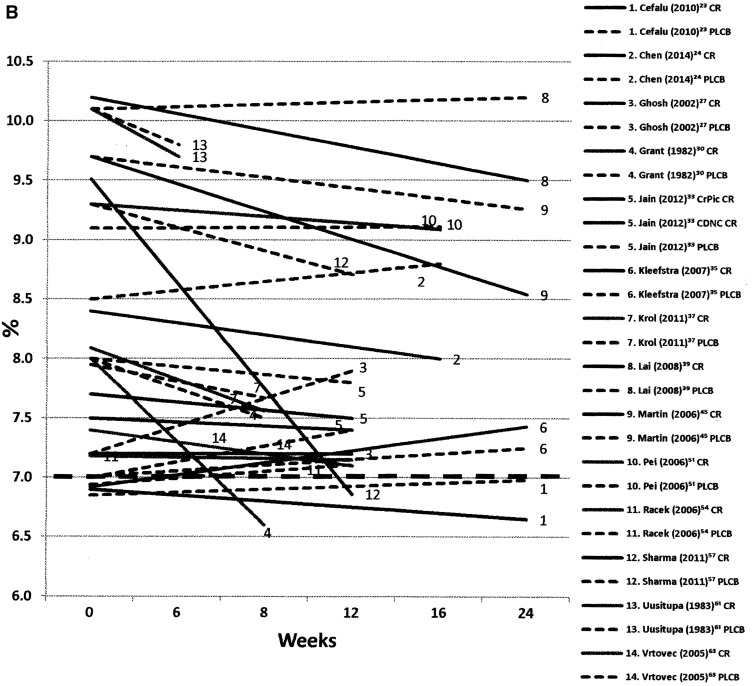

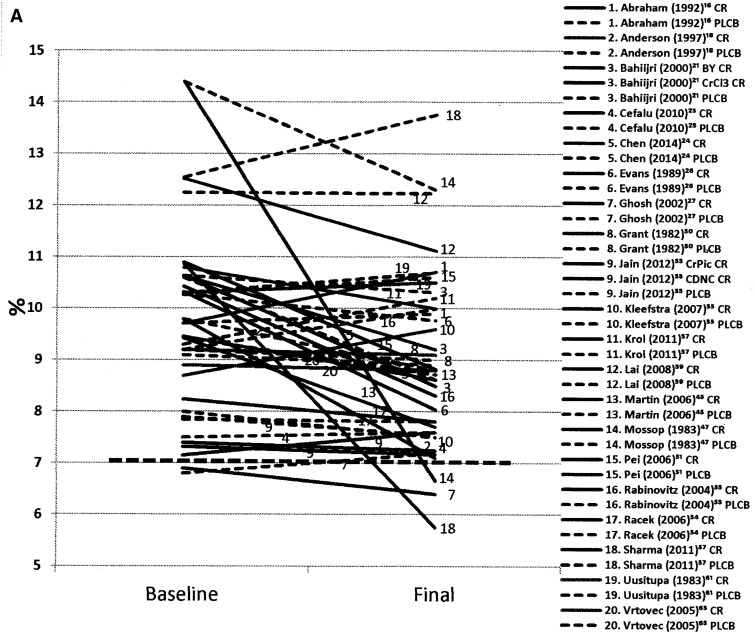

Figure 3A displays mean changes from baseline to post supplementation in FPG in patients enrolled in the chromium supplementation and placebo arms of the RCTs. Sixteen of the 20 studies enrolled patients on hypoglycemic agents, most of whom were also on lifestyle modifications. Figures 3A and 3B also show the treatment goals for FPG. Mean levels in all the studies at baseline were above the FPG levels considered diagnostic for diabetes. In general, mean FPG did not change or decreased only slightly with the chromium supplement, but, as is evident in the figure, they rarely reached normal levels, and supplementation appeared to have only modest effects on FPG. Again, in 10 studies, the FPG levels in the placebo arm also decreased. Large changes were noted in the placebo arms of 2 studies; in a single-blind study,57 FPG increased from 12.6 to 13.8 mmol/L (eg, 226–248 mg/dL), and in the other study, in which 26 (13 on chromium and 13 controls) of 39 subjects had dropped out,47 FPG decreased from 14.4 to 12.3 mmol/L (259–221 mg/dL). Striking changes in FPG were not evident in the remainder of studies, and values generally remained above treatment goals.

Figure 3.

(A) Mean changes in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) from baseline to postchromium supplementation for all 20 studies (22 arms) and placebo arms. olid line is chromium treatment, dashed line is placebo control, and heavy dotted line represents FPG treatment goal of ≤7.2 mmol/L.8 (B) Mean changes in FPG by length of study, from pre- to postchromium supplementation, for 20 studies (22 arms) and placebo arms. Solid line is chromium treatment, dashed line is placebo control, and heavy dotted line represents FPG treatment goal of ≤7.2 mmol/L.8 Abbreviations: BY, brewer’s yeast; CDNC, chromium dinicocysteinate; CR, chromium; CrCl3, chromium chloride; CrPic, chromium picolinate; PLCB, placebo.

Figure 3B shows the same data by duration of the chromium supplementation; again, duration did not seem to dramatically affect FPG levels. Fasting plasma glucose outcomes for patients concurrently receiving hypoglycemic drugs and chromium supplements were not markedly different from those in patients on chromium supplements alone.

In summary, hypoglycemic treatment goals were reached after chromium supplementation in 25% (5 of 20) of studies using the mean FPG criterion, in 21% (3 of 14) using the HbA1c criterion, and in 7% (1 of 14) using both the FPG and the HbA1c criteria. Using the decline in HbA1c by >0.5%, only 36% (5 of 14) met this criterion. In most cases, these effects were achieved only when chromium supplementation was administered along with conventional hypoglycemic medications and lifestyle modifications.

There were some lesser declines observed in glucose measures during chromium supplementation in 70% of studies (14 of 20) with FPG measures, in 43% of studies (6 of 14) with HbA1c measures, and in 38% of studies (6 of 16) with both measures. But, as can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, declines were small, and in some cases declines were seen in the placebo arms as well, suggesting that the use of hypoglycemic medications and lifestyle modifications had also changed.

As seen in Figure 1, the majority of the studies (16 of 20) involved patients who were also taking hypoglycemic drugs, usually oral hypoglycemic agents, as well as chromium supplements. One study of patients who were not receiving hypoglycemic medications was of particular interest and was therefore examined in greater depth in an attempt to discover similarities that might account for the favorable responses. The Sharma et al.57 trial enrolled subjects in India with newly diagnosed T2DM. Although it was small (n = 20 subjects) and its duration was only 12 weeks, it was well controlled and employed an ITT design, so that the strengths of randomization were preserved. The drop in FPG from 10.9 to 5.8 mmol/dL (or from 196 to 104 mg/dL) after supplementation was impressive. In that study, the chromium supplement alone brought the mean FPG of patients into the normal range without the use of hypoglycemic drug therapy. Clinically meaningful drops were also evident in HbA1c, although variability in response was considerable, perhaps suggesting differential adherence.

In addition to the Sharma et al.57 study, there were 2 other trials of patients who did not take hypoglycemic medications, but the analysis of study results was flawed. The Mossop,47 trial conducted in Africa, showed decreases in FPG, but the number of dropouts was considerable (of the 39 patients at baseline, only 13 on the chromium intervention completed the study), and noncompliers and dropouts were excluded from the analysis (ie, per-protocol, not ITT). Thus, it was difficult to ascertain whether there was a supplementation effect. The trial by Anderson et al.,18 done in China using very high doses of chromium picolinate (1000 µg/d), was larger (n = 60) and longer (16 wk) than the prior study. However, it also used a per-protocol design that focused only on completers (52 of 60) in the 1000-µg arm, and so here, too, the principles of randomization were violated. Mean values prior to supplementation were not provided for the 200-µg arm, thus precluding an analysis.

EVALUATING THE IMPACT OF CHROMIUM ON GLYCEMIC CONTROL, DESPITE HETEROGENEITY IN STUDIES

Chromium supplements on the market today vary widely in dose (usually providing and rarely exceeding ≈500 µg/serving) and form (brewer’s yeast, chromium picolinate, chromium chloride, and other proprietary formulations). The manufacturers of 3 trademarked chromium-containing supplements (Chromax[chromium picolinate], ChromeMate [chromium polynicotinate], and Zychrome [chromium diniccocysteinate]) have self-declared that their formulations are generally recognized as safe (GRAS).67 The present analysis revealed so many other factors that varied between the studies that it was impossible to determine if the form or the dose of the supplement had clinically significant effects. For example, as shown in Figure 1 and further detailed in Table S1 in the Supporting Information online, those studies in which subjects were consuming a chromium supplement at >500 µg/d concurrent with hypoglycemic drugs numbered only 5 and reflected 3 different formulations of chromium: picolinate, chromium III, and a yeast preparation, thus making interpretation of any trends impossible.

Six meta-analyses of RCTs on the topic of chromium supplements and glucose metabolism in T2DM patients and published between 2001 and 2014 met the criteria established for this review. Many included the same studies, so the analyses were not independent. Two-thirds (4 of 6) of them concluded that chromium supplements had a significant and positive effect on lowering FPG or HbA1c in patients with T2DM. However, it is questionable whether the totality of the evidence could be synthesized in a meaningful meta-analysis of these meta-analyses because the trials were so heterogeneous in treatment groups, study duration, forms of chromium, methods of analysis, and other characteristics. Even in the meta-analysis by Patal et al.,11 with criteria that were restricted to T2DM subjects on chromium picolinate for more than 3 months, extremely high levels of heterogeneity were noted on statistical testing, suggesting that other possible variables were influencing outcomes and were not controlled, which led the authors to conclude that a strong recommendation to use supplements was not justified.

The quality of some of the extant meta-analyses was also questionable. None of the 6 meta-analyses specifically stated whether they followed the PRISMA guidelines.68 Two authors used the Cochrane Collaboration review template,11,14 and one meta-analysis was performed under contract with the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, with rigorous descriptions of each study.10 Both the meta-analysis by Balk et al.10 and the first meta-analysis published in 20029 were published before the PRISMA guidelines were released.

Much different and less positive conclusions were reached in the present narrative review than in the meta-analyses. As Sigman69 described so well, meta-analyses often combine studies with dissimilar populations, disparate inclusion and exclusion criteria, and designs of different rigor for statistical analysis as well as many other discrepancies and subjective decisions that may have had significant impacts on the conclusions. Moreover, the presence of statistical significance in the meta-analyses did not signify that clinically significant decreases were achieved. Thus, the completeness and consistency of systematic reviews and meta-analyses are dependent on the validity and overall strength of the primary studies that they include. It is important for researchers to provide an adequate description of the methodology employed in their studies to make it possible to replicate them. Randomized controlled clinical trials in nutrition are particularly challenging. Nutrient effects are typically polyvalent in scope, with small effect sizes that may be within the “noise” range of biological variability, and are often of a sigmoid character, with useful responses occurring only across a portion of the intake range. In contrast, drug effects tend to be monovalent, monotonic, and larger in their effect sizes and have responses that vary in proportion to dose.70 Standardized procedures have been developed to support provision of the evidence needed for credible systematic reviews involving dietary constituents,10,71,72 but not all published systematic studies or meta-analyses use them.

The results of the present analysis might appear at first glance to be at variance with a recent cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, which found that a quarter of those who are supplement users in the United States consumed chromium-containing supplements and that the odds of having T2DM were lower in those who did so.73 However, less than 1% of those taking chromium supplements were consuming supplements that listed chromium in the product title on the label, suggesting single-ingredient supplement use. Moreover, it is well known that supplement users tend to be healthier, less likely to be overweight, and different in many other respects that may have affected the risk of T2DM.

Readers often find it surprising that meta-analyses of seemingly the same question come to very different conclusions, as was the case in this exercise. Although the meta-analyses seemed to ask the same questions, upon further inspection it was found that the study populations of patients with T2DM varied in many of their comorbidities, in whether they were simultaneously being treated with oral and other hypoglycemic agents in the dose, form, and type of the chromium supplement provided, and in the duration of supplementation. In 10 studies, results in the placebo arm also decreased during supplementation, suggesting that hypoglycemic medications or lifestyle modifications may have also changed during the experimental periods. It is not appropriate to perform meta-analyses of studies that show considerable variability in treatment and populations. This variability hampered comparison of the studies with each other and made it difficult to answer the clinically relevant questions that were posed. The meta-analyses were published in years ranging from 2002 to 2014, with the result that some studies were omitted in the earlier meta-analyses simply because the RCTs were published after the review had been completed.

Although many RCTs on chromium supplements had been performed, studies with well-defined types of chromium and supplement doses using patients with T2DM who were not taking other hypoglycemic drugs and were analyzed using ITT designs were very few and were performed only in small numbers of subjects. The possibility of pleotropic effects due to these and other causes cannot be excluded. Finally, it was disappointing that many of the RCTs lost the advantages of causal inference of the randomization because they analyzed only the completers (per-protocol analysis) and did not employ an ITT design. The meta-analyses, therefore, came to somewhat different conclusions because of the myriad ways in which they differed from each other, although they seemed to address the same question.

The present examination of mean changes in FPG and HbA1c from pre- to postsupplementation in the actual clinical trials that were evaluated gave a somewhat clearer picture, but the effects were not impressive. The total number of studies in which mean changes reached treatment goals were at 20% at best; 3 out of 14 for HbA1c and 5 out of 20 for FBG, or 1 out of 14 studies for both.

In patients with diabetes, a chromium supplement had, at best, a small positive beneficial effect in lowering FPG and HbA1c when it was added to a standard hypoglycemic medication schedule. Although there were a few studies in which there were significant FPG or HbA1c decreases with the chromium supplement, both of these biomarkers, when taken together, decreased in these medicated diabetic patients in only 7 of 14 studies (50%). The effects noted in the supplemented groups could have been due not to the chromium supplement itself, but were likely attributable to the hypoglycemic medications and lifestyle advice the patients received as well as to changes in adherence to these over the course of the supplement trial. Such changes in adherence during supplementation may have accounted for some or all of these changes. The presence of a placebo somewhat, but not totally, allayed these concerns.

The findings of this review are in line with those of several authoritative groups. In 2012 the Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee stated that dietary supplements (called natural health products in Canada) were not recommended for glycemic control in individuals with diabetes because at that time there was insufficient evidence regarding efficacy and safety (grade D, consensus finding). The Canadian review stated that the studies on chromium appeared to report conflicting effects on HbA1C in patients with T2DM in trials of at least 3 months.74 In 2014 the American Diabetes Association’s Standards of Care noted there was insufficient evidence to support the routine use of micronutrients such as chromium to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes, and they gave the practice a grade of C.8 The findings of the present review uphold these recommendations and provide additional support for the existing guidelines.

In addition to efficacy, the safety of chromium supplements is an issue of concern in the studies discussed in this review, since only half (11 of 20) of the RCTs addressed adverse events. In those studies that did report adverse events, mostly minor side effects were noted, such as skin rash, constipation, and other gastrointestinal symptoms (ie, decreased appetite and flatulence). The National Toxicology Program stated in 2003 that chromium picolinate, the form of trivalent chromium most widely used in dietary supplements, was one of the least toxic of the nutrients, that it lacked toxic effects, and that it was unlikely that doses up to 1000 µg/d would be toxic.75 Therefore, although there may be little evidence of concern about the lack of safety of chromium supplements at the dose levels used in the studies this review, whether these products have clinically meaningful effects on glycemic control remains to be determined.

The strengths of this study are that it included all available RCTs addressing the clinical question posed and is, as far as can be determined, the most up-to-date systematic review of the topic, with detailed consideration of dose and duration of supplementation in T2DM patients, most of whom were already on medication and presumably counseled to make lifestyle changes. One limitation of the study is that means, rather than individual clinical data, were used. A second limitation may be the outcome criteria that were used. This review focused on FPG and HbA1c, which are widely accepted biomarkers that the American Diabetes Association recommends for diagnosing and monitoring diabetic status. Fasting plasma glucose levels are used by Medicare for the diagnosis of diabetes and are also used by the US Food and Drug Administration to ascertain the efficacy of dietary supplements and drugs. It is possible that more complex procedures for diagnosing and monitoring treatment effects in T2DM patients might give different results These include calculating the area under the curve for blood glucose or insulin response over time after a standard glucose challenge, or applying the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance, which is often used to describe the degree of glycemic impairment. However, the threshold levels used to define insulin resistance in the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance vary, and values may also be age and gender specific76; moreover, for practical purposes, these tools are rarely used clinically.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, after a thorough review of RCTs relevant to the issue, there is still little reason to recommend chromium dietary supplements to achieve clinically meaningful improvements in glycemic control. Major safety issues were not present in these studies. It is recommended that healthcare practitioners urge patients with T2DM to continue using their prescribed hypoglycemic agents and make appropriate lifestyle changes in diet and physical activity. Future meta-analyses should include only high-quality studies with similar forms of chromium and comparable inclusion/exclusion criteria to provide scientifically sound recommendations for clinicians. Until adequately powered trials that control for issues of nutrient formulations, bioavailability, background diets, and medication use provide more conclusive evidence of the efficacy of chromium supplements, the support at present for health professionals to recommend the use of chromium supplements for glycemic control in patients with diabetes is lacking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joyce Merkel, MS, RD, and Edwina Wambogo, MS, MPH, RD, LDN, at the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements for their editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding/support. This work was supported by the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Partial support was also provided by the US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, under agreement no. 58-1950-0-014.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of Dietary Supplements, the National Institutes of Health, or any other entity of the US government.

Supporting Information

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of this article at the publisher's website:

Table S1 Chromium supplementation and glycemic control: study design features

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Statistics about diabetes– overall numbers, diabetes and prediabetes. http://www.diabetes.org/diabetes-basics/statistics/. Last reviewed May 18, 2015. Accessed June 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (US) Panel on Micronutrients. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium, and Zinc. Washington, DC, USA: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Miller PE, et al. Why US adults use dietary supplements. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent JB. The biochemistry of chromium. J Nutr. 2000;130:715–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeejeebhoy KN, Chu RC, Marliss EB, et al. Chromium deficiency, glucose intolerance, and neuropathy reversed by chromium supplementation, in a patient receiving long-term total parenteral nutrition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:531–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RO, Forloines-Lynn S, Cross RE, et al. Chromium deficiency after long-term total parenteral nutrition. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Food and Drug Administration. Qualified health claims: letter of enforcement discretion – chromium picolinate and insulin resistance (docket no. 2004Q-0144). August 25, 2005; http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm073017.htm. Accessed June 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Althuis MD, Jordan NE, Ludington EA, et al. Glucose and insulin responses to dietary chromium supplements: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balk EM, Tatsioni A, Lichtenstein AH, et al. Effect of chromium supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipids: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2154–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patal PC, Cardino MT, Jimeno CA. A meta-analysis on the effect of chromium picolinate on glucose and lipid profiles among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Philipp J Intern Med. 2010;48:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdollahi M, Farshchi A, Nikfar S, et al. Effect of chromium on glucose and lipid profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes; a meta-analysis review of randomized trials. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2013;16:99–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey CH. Improved meta-analytic methods show no effect of chromium supplements on fasting glucose. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2014;157:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suksomboon N, Poolsup N, Yuwanakorn A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of chromium supplementation in diabetes. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2014;39:292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Albarracin CA, Fuqua BC, Evans JL, et al. Chromium picolinate and biotin combination improves glucose metabolism in treated, uncontrolled overweight to obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham AS, Brooks BA, Eylath U. The effects of chromium supplementation on serum glucose and lipids in patients with and without non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Metabolism. 1992;41:768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghdassi E, Arendt BM, Salit IE, et al. In patients with HIV-infection, chromium supplementation improves insulin resistance and other metabolic abnormalities: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Curr HIV Res. 2010;8:113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson RA, Cheng N, Bryden NA, et al. Elevated intakes of supplemental chromium improve glucose and insulin variables in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1997;46:1786–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson RA, Polansky MM, Bryden NA, et al. Chromium supplementation of human subjects: effects on glucose, insulin, and lipid variables. Metabolism. 1983;32:894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RA, Polansky MM, Bryden NA, et al. Supplemental-chromium effects on glucose, insulin, glucagon, and urinary chromium losses in subjects consuming controlled low-chromium diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bahijiri SM, Mira SA, Mufti AM, et al. The effects of inorganic chromium and brewer's yeast supplementation on glucose tolerance, serum lipids and drug dosage in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:831–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cefalu WT, Bell-Farrow AD, Stegner J, et al. Effect of chromium picolinate on insulin sensitivity in vivo. J Trace Element Exp Med. 1999;12:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cefalu WT, Rood J, Pinsonat P, et al. Characterization of the metabolic and physiologic response to chromium supplementation in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2010;59:755–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YL, Lin JD, Hsia TL, et al. The effect of chromium on inflammatory markers, 1st and 2nd phase insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Nutr. 2014;53:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford V, Scheckenbach R, Preuss HG. Effects of niacin-bound chromium supplementation on body composition in overweight African-American women. Diabetes Obes Metab. 1999;1:331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans GW. The effect of chromium picolinate on insulin controlled parameters in humans. Int J Biosocial Med Res. 1989;11:163–180. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh D, Bhattacharya B, Mukherjee B, et al. Role of chromium supplementation in Indians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Nutr Biochem. 2002;13:690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunton JE, Cheung NW, Hitchman R, et al. Chromium supplementation does not improve glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, or lipid profile: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of supplementation in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:712–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant AP, McMullen JK. The effect of brewers yeast containing glucose tolerance factor on the response to treatment in Type 2 diabetics. A short controlled study. Ulster Med J. 1982;51:110–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant KE, Chandler RM, Castle AL, et al. Chromium and exercise training: effect on obese women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:992–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermann J, Chung H, Arquitt A, et al. Effects of chromium or copper supplementation on plasma lipids, plasma glucose and serum insulin in adults over age fifty. J Nutr Elderly. 1998;18:27–45. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hermann J, Arquitt A, Stoecker B. Effects of chromium supplementation on plasma lipids, apolipoproteins, and glucose in elderly subjects. Nutr Res. 1994;14:671–674. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain SK, Kahlon G, Morehead L, et al. Effect of chromium dinicocysteinate supplementation on circulating levels of insulin, TNF-α, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic subjects: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2012;56:1333–1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joseph LJ, Farrell PA, Davey SL, et al. Effect of resistance training with or without chromium picolinate supplementation on glucose metabolism in older men and women. Metabolism. 1999;48:546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Bakker SJ, et al. Chromium treatment has no effect in patients with type 2 diabetes in a Western population: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1092–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleefstra N, Houweling ST, Jansman FG, et al. Chromium treatment has no effect in patients with poorly controlled, insulin-treated type 2 diabetes in an obese Western population: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krol E, Krejpcio Z, Byks H, et al. Effects of chromium brewer's yeast supplementation on body mass, blood carbohydrates, and lipids and minerals in type 2 diabetic patients. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2011;143:726–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iqbal N, Cardillo S, Volger S, et al. Chromium picolinate does not improve key features of metabolic syndrome in obese nondiabetic adults. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2009;7:143–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai MH. Antioxidant effects and insulin resistance improvement of chromium combined with vitamin C and E supplementation for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2008;43:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lefavi RG, Wilson GD, Keith RE, et al. Lipid-lowering effect of dietary chromium (III)–nicotinic acid complex in male athletes. Nutr Res. 1993;13:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee NA, Reasner CA. Beneficial effect of chromium supplementation on serum triglyceride levels in NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:1449–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li YC, Shin SJ, Chen JC. Effects of brewer’s yeast and torula yeast on glucose tolerance, serum lipids and chromium contents in adult human beings. J Chin Nutr Soc. 1992;17:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YC. Effects of brewer’s yeast on glucose tolerance and serum lipids in Chinese adults. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1994;41:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lucidi RS, Thyer AC, Easton CA, et al. Effect of chromium supplementation on insulin resistance and ovarian and menstrual cyclicity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:1755–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin J, Wang ZQ, Zhang XH, et al. Chromium picolinate supplementation attenuates body weight gain and increases insulin sensitivity in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1826–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez OB, MacDonald AC, Gibson RS, et al. Dietary chromium and effect of chromium supplementation on glucose tolerance of elderly Canadian women. Nutr Res. 1985;5:609–620. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mossop RT. Effects of chromium III on fasting blood glucose, cholesterol and cholesterol HDL levels in diabetics. Cent Afr J Med. 1983;29:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Offenbacher EG, Pi-Sunyer FX. Beneficial effect of chromium-rich yeast on glucose tolerance and blood lipids in elderly subjects. Diabetes. 1980;29:919–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Offenbacher EG, Rinko CJ, Pi-Sunyer FX. The effects of inorganic chromium and brewer's yeast on glucose tolerance, plasma lipids, and plasma chromium in elderly subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasman WJ, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Saris WH. The effectiveness of long-term supplementation of carbohydrate, chromium, fibre and caffeine on weight maintenance. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pei D, Hsieh CH, Hung YJ, et al. The influence of chromium chloride–containing milk to glycemic control of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Metabolism. 2006;55:923–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabinowitz MB, Gonick HC, Levin SR, et al. Effects of chromium and yeast supplements on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in diabetic men. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rabinovitz H, Friedensohn A, Leibovitz A, et al. Effect of chromium supplementation on blood glucose and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes mellitus elderly patients. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2004;74:178–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Racek J, Trefil L, Rajdl D, et al. Influence of chromium-enriched yeast on blood glucose and insulin variables, blood lipids, and markers of oxidative stress in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;109:215–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riales R, Albrink MJ. Effect of chromium chloride supplementation on glucose tolerance and serum lipids including high-density lipoprotein of adult men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:2670–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singer GM, Geohas J. The effect of chromium picolinate and biotin supplementation on glycemic control in poorly controlled patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized trial. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2006;8:636–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma S, Agrawal RP, Choudhary M, et al. Beneficial effect of chromium supplementation on glucose, HbA1C and lipid variables in individuals with newly onset type-2 diabetes. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2011;25:149–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sherman L, Glennon JA, Brech WJ, et al. Failure of trivalent chromium to improve hyperglycemia in diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 1968;17:439–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thomas VL, Gropper SS. Effect of chromium nicotinic acid supplementation on selected cardiovascular disease risk factors. Biol Trace Elem Res. 1996;55:297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urberg M, Zemel MB. Evidence for synergism between chromium and nicotinic acid in the control of glucose tolerance in elderly humans. Metabolism. 1987;36:896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uusitupa MI, Kumpulainen JT, Voutilainen E, et al. Effect of inorganic chromium supplementation on glucose tolerance, insulin response, and serum lipids in noninsulin-dependent diabetics. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:404–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Volpe SL, Huang HW, Larpadisorn K, et al. Effect of chromium supplementation and exercise on body composition, resting metabolic rate and selected biochemical parameters in moderately obese women following an exercise program. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:293–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vrtovec M, Vrtovec B, Briski A, et al. Chromium supplementation shortens QTc interval duration in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Heart J. 2005;149:632–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walker LS, Bemben MG, Bemben DA, et al. Chromium picolinate effects on body composition and muscular performance in wrestlers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1730–1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang MM, Fox EA, Stoecker BJ, et al. Serum cholesterol of adults supplemented with brewer’s yeast or chromium chloride. Nutr Res. 1989;9:989–998. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson BE, Gondy A. Effects of chromium supplementation on fasting insulin levels and lipid parameters in healthy, non-obese young subjects. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1995;28:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.AIBMR Life Sciences. GRAS self-determination inventory database. Puyallap, WA: AIBMR Life Sciences, Inc; http://www.aibmr.com/resources/GRAS-database.php. Accessed June 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sigman M. A meta-analysis of meta-analyses. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:11–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Blumberg J, Heaney RP, Huncharek M, et al. Evidence-based criteria in the nutritional context. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Costello RB, Lentino CV, Saldanha L, et al. A select review reporting the quality of studies measuring endothelial dysfunction in randomised diet intervention trials. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chung M, Balk EM, Ip S, et al. Reporting of systematic reviews of micronutrients and health: a critical appraisal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1099–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McIver DJ, Grizales AM, Brownstein JS, et al. Risk of type 2 diabetes is lower in US adults taking chromium–containing supplements. J Nutr. 2015;145:2675–2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee, Nahas R, Goguen J. Natural health products. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppl 1):S97–S99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heimbach JT. Chromium: recent studies regarding nutritional roles and safety. Nutr Today. 2005;40:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gayoso-Diz P, Otero-Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Alvarez MX, et al. Insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) cut-off values and the metabolic syndrome in a general adult population: effect of gender and age: EPIRCE cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;13:47 doi:10.1186/1472-6823-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.