Abstract

FTY720 (fingolimod) is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drug to treat relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. FTY720 treatment in pregnant inbred LM/Bc mice results in approximately 60% of embryos having a neural tube defect (NTD). Sphingosine kinases (Sphk1, Sphk2) phosphorylate FTY720 in vivo to form the bioactive metabolite FTY720-1-phosphate (FTY720-P). Cytoplasmic FTY720-P is an agonist for 4 of the 5 sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors (S1P1, 3-5) and can also act as a functional antagonist of S1P1, whereas FTY720-P generated in the nucleus inhibits histone deacetylases (HDACs), leading to increased histone acetylation. This study demonstrates that treatment of LM/Bc mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with FTY720 results in a significant accumulation of FTY720-P in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Elevated nuclear FTY720-P is associated with decreased HDAC activity and increased histone acetylation at H3K18 and H3K23 in LM/Bc MEFs. Treatment of LM/Bc MEFs with FTY720 and a selective Sphk2 inhibitor, ABC294640, significantly reduces the amount of FTY720-P that accumulates in the nucleus. The data provide insight into the relative amounts of FTY720-P generated in the nuclear versus cytoplasmic subcellular compartments after FTY720 treatment and the specific Sphk isoforms involved. The results of this study suggest that FTY720-induced NTDs may involve multiple mechanisms, including: (1) sustained and/or altered S1P receptor activation and signaling by FTY720-P produced in the cytoplasm and (2) HDAC inhibition and histone hyperacetylation by FTY720-P generated in the nucleus that could lead to epigenetic changes in gene regulation.

Keywords: FTY720, S1P receptors, histone deacetylase inhibition, histone post-translational modification (PTM), ABC294640, sphingosine kinase

FTY720, or fingolimod, is an immunomodulator that was designed in the early 1990s by simplifying the structure of the antibiotic, ISP-1, a metabolite of the fungus Isaria sinclairii (Adachi et al., 1995) and several other fungi that produce structurally identical metabolites (myriocin and thermozymocidin; Riley and Plattner, 2000). Initial in vitro and in vivo studies of FTY720 demonstrated significant immunosuppressive activity and increased safety over ISP-1, making it a viable candidate for use in organ transplants and treatment of autoimmune diseases (Adachi et al., 1995). Administration of FTY720 results in sequestration of lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs (Brinkmann et al., 2000). In 2010, FTY720 (Gilenya, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) (National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 2015b).

FTY720 can be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases (Sphk1, Sphk2) to form bioactive FTY720-1-phosphate (FTY720-P) (Brinkmann et al., 2002; Mandala et al., 2002) (Figure 1). Both kinases are capable of phosphorylating the parent compound, but Sphk2 is considerably more efficient (Billich et al., 2003; Paugh et al., 2003). FTY720-P is primarily dephosphorylated by lipid phosphate phosphatase 3 (LPP3, Ppap2b), although LPP1 and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) phosphatase 1 (Sgpp1) may have some activity (Mechtcheriakova et al., 2007; Yamanaka et al., 2008). Due to the structural similarity between FTY720 and sphingosine, it was initially hypothesized that FTY720-P could function as a ligand for S1P receptors. S1P receptors are a family of G protein-coupled receptors that play an important role in many biological processes, including neural cell communication, immune cell trafficking, and vascular homeostasis (reviewed in Brinkmann, 2007). FTY720-P can be transported out of the cell by Spinster 2 (Spns2) (Hisano et al., 2011), where it can act as a potent S1P receptor agonist, binding to 4 of the 5 S1P receptors: S1P1, 3-5 (Brinkmann et al., 2002; reviewed in Brinkmann 2007). It has also been shown that FTY720-P can act as a functional antagonist for the S1P1 receptor by targeting it for degradation following binding/internalization (Brinkmann et al., 2004; Gräler and Goetzl, 2004). S1P1 is highly expressed on T- and B-lymphocytes and has a significant role in lymphocyte trafficking, suggesting a mechanism of action for FTY720-P in the sequestration of lymphocytes (Gräler and Goetzl, 2004).

FIG. 1.

FTY720 metabolism. FTY720 can be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases (Sphk1, Sphk2) to form bioactive FTY720-1-P (FTY720-P). Although both Sphk1 and Sphk2 are capable of phosphorylating FTY720, Sphk2 is more efficient. Cytoplasmic FTY720-P can be transported out of the cell by Spinster 2 (Spns2) where it can then act as an agonist on 4 of the 5 sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptors: S1P1,3-5. Nuclear FTY720-P has been shown to bind to the active site of histone deacetylases (HDACs) and inhibit their activity. Inhibition of HDACs results in increased histone acetylation. FTY720-P is primarily dephosphorylated by lipid phosphatase 3 (LPP3), while LPP1 and S1P phosphatase 1 (SPP1) may be able to dephosphorylate FTY720-P as well.

Serious cardiovascular complications (eg, bradycardia and hypertension) (reviewed in Behjati et al., 2014) can occur with FTY720 treatment, including the potential for fetal harm (Novartis, 2014). FTY720 has a pregnancy category C rating, based on studies in pregnant rats and rabbits that have demonstrated FTY720’s teratogenicity (Novartis, 2014). Karlsson et al. (2014) followed 66 pregnant women taking FTY720 prior to or during pregnancy. Of those pregnancies, 36% were electively terminated, with at least 4 cases involving fetal abnormalities or abnormal pregnancies. Of the remaining pregnancies, approximately 24% were spontaneously aborted, approximately 70% resulted in a healthy baby, and approximately 5% were newborns with congenital abnormalities (skeletal malformations and acrania). Gelineau-van Waes et al. (2012) demonstrated that FTY720 treatment in LM/Bc mice causes exencephaly in embryos. Exencephaly is a severe and lethal neural tube defect (NTD) similar to anencephaly in humans. Pregnant LM/Bc mice were given an oral dose of FTY720 on gestational days 6.5 through 8.5. After treatment, 61% of LM/Bc embryos were exencephalic (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). FTY720 and FTY720-P were detected in maternal blood and tissues, and both compounds were also present in embryonic tissue, demonstrating that FTY720 and/or FTY720-P are capable of crossing the placenta (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012).

Most of the research concerning FTY720-P has focused on its role as a ligand for cell surface S1P receptors and on its immunosuppressive actions. However, Hait et al. (2014) recently demonstrated that in addition to cytoplasmic/extracellular localization of FTY720-P, overexpression of Sphk2 also generates FTY720-P in the nucleus that can bind to and inhibit Class I histone deacetylases (HDACs). HDAC inhibition by nuclear FTY720-P caused increased acetylation of histone lysine residues at H2BK12, H3K9, and H4K5 in human neuroblastoma cells. Other known HDAC inhibitors, such as valproic acid (VPA) and trichostatin A (TSA), have been shown to cause NTDs in mice and humans (Svensson et al., 1998; reviewed by Wiltse, 2005). The purpose of this study was to determine whether FTY720 treatment of spontaneously immortalized LM/Bc mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) would result in increased nuclear FTY720-P accumulation, HDAC inhibition, and increased histone acetylation. Establishing a role for elevated nuclear FTY720-P, HDAC inhibition, and induction of epigenetic changes could provide significant insight into understanding potential mechanisms involved in aberrant gene regulation and teratogenicity following exposure to FTY720 during pregnancy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MEF cell lines and treatments

Strain-specific MEF cell lines were generated from gestational day 12.5 fetuses harvested from untreated LM/Bc mice and cultured using a previously described method (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). The MEFs used in the following experiments were generated from the same embryo as those MEFs used in the previous studies by our lab (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). Spontaneously immortalized MEFs were cultured at a density of 200 000 cells per plate in 100-mm dishes for 48 h followed by a change of 10% fetal bovine serum-containing media. At the time of media change, cells were treated with vehicle (sterile saline) or 1 µM FTY720 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) and incubated for an additional 24 h. For experiments utilizing the selective Sphk1 inhibitor PF-543 (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts), MEFs were grown for 48 h, then simultaneously treated with vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] and sterile saline), 500 nM or 1 µM PF-543, and/or 1 µM FTY720 at the time of media change. For experiments utilizing ABC294640 (MedKoo Biosciences, Chapel Hill, North Carolina), a selective Sphk2 inhibitor, MEFs were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 25 µM or 50 µM ABC294640 at the time of media change and allowed to grow for another 24 h. After the 24 h pretreatment with the inhibitor, MEFs were treated with vehicle (sterile water) or 1 µM FTY720. These experiments replicate optimized conditions for PF-543 and ABC294640 concentration and treatment duration previously established in other labs (French et al., 2010; Schnute et al., 2012). Treatments did not appear to have a significant effect on cell viability, as MEFs continued to replicate and actively grow throughout the entire treatment period. At the end of the incubation period, MEFs were collected using various methods depending on the subsequent assays. To isolate MEFs into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) was used. The HDAC Activity Assay (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) was used to isolate the nuclei from the strain-specific MEFs. A Histone Purification Mini Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, California) was used to extract purified histones for western blot analysis. Manufacturer’s protocols were followed with a few minor modifications, such as the addition of phosphatase inhibitors, as noted below.

Isolation of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions

Nuclear and cytoplasmic cell fractions were isolated from control and treated MEFs for analysis of FTY720 and FTY720-P using a slight modification of the NE-PER kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) manufacturer’s protocol as noted. Cells were grown to subconfluence, washed with sterile PBS and harvested using Trypsin-EDTA. Reagent volumes for a packed cell volume of 10 µl were used. CER I and NER also contained HALT Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Final- 1X) and additional phosphatase inhibitors and protease inhibitor to ensure that FTY720-P would remain phosphorylated. The additional inhibitors used were sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4) at 1 mM, sodium fluoride (NaF) at 10 mM, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) at 0.5 mM. Maximum speed of the microcentrifuge used was 20 800 × g. Protein concentrations for the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were determined by Bradford Assay. Aliquots of 100–200 µg of nuclear and 400–600 µg cytoplasmic cell fractions were frozen at −80°C until they were analyzed for FTY720 and FTY720-P by high performance liquid chromatography tandem linear-ion trap electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS).

Mass spectrometry analysis of FTY720 and FTY720-P

FTY720 and FTY720-P were quantified by LC-ESI-MS/MS using the method described in Zitomer et al. (2008, 2009). FTY720 and FTY720-1-P from MEF cell fractions (100–600 µg protein—based on cell fraction) were extracted in 1.0 ml of 1:1 acetonitrile:water made to 5% with formic acid and containing known amounts (36 pmol total) of C20-dihydrosphingosine (C20-Sa, d20:0) (Matreya, Pleasant Gap, Pennsylvania) and D-erythro-C17-sphingosine-1-phosphate (C17-S1P) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, Alabama) as internal standards. The extracts were analyzed for the internal and external standards, as well as FTY720 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) and FTY720-P (US Biological Corporation, Salem, Massachusetts). LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of the extracts was conducted using a Finnigan Micro AS autosampler coupled to a Surveyor MS pump (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts). Separation was accomplished using an Imtakt Cadenza 3-μm particle size CW-C18 column, 150 × 2 mm (Imtakt USA, Portland, Oregon). The column effluent was directly coupled to a Finnigan LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer. Details of the liquid chromatography and mass spectrometer settings can be found in Zitomer et al. (2008, 2009). Quantification of FTY720 and FTY720-phosphate was accomplished by comparing the integrated area for the known quantity of the appropriate internal or external standard to the area of the analyte.

HDAC activity

The nuclear cell fraction was isolated from control and FTY720-treated MEFs for determination of HDAC activity using a slight modification of the Cayman HDAC Activity Assay (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) manufacturer’s protocol. Lysis buffer, resuspension buffer, and extraction buffer were all made as instructed, but additional phosphatase and protease inhibitors (1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 0.5 mM PMSF) were added to prevent dephosphorylation of FTY720-P. Extracted nuclei were placed in an ice bath and sonicated, using an immersion tip sonicator, for 10 s, followed by 30 s of rest, and then sonicated for another 10 s. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Samples were diluted in extraction buffer so that all samples were equal concentrations (0.2 mg/ml) before being added to the assay. Technical duplicates of standards, positive controls (using HDAC1), and sample wells with and without TSA were utilized for data analysis. The assay was conducted using the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was read on a SpectraMax 3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, California) with SoftMax Pro 5.4.1 software using an excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 453 nm. The average fluorescence of each sample and standard was calculated and the average fluorescence of the blank standard was subtracted from itself and all other standards to create corrected value, which were then graphed to create the deacetylated standard curve. To determine the corrected fluorescence of the samples, the average of the TSA-treated sample was subtracted from the average of the corresponding samples. The deacetylated concentrations were calculated from the corrected values and the linear regression equation of the standard curve. HDAC activity was then in turn calculated from deacetylated concentrations and protein concentrations.

Histone purification

Histone Purification Mini Kits (40026, Active Motif; Carlsbad, California) were used to isolate and purify histones from control and FTY720-treated MEFs. Cells were washed twice with prewarmed serum-free medium, 800 µl of extraction buffer was added to the cells, and a cell scraper was used to remove the cells, which were then transferred to a microcentrifuge tube. The cell-containing tubes were placed on a rotating platform at 4°C for 2 h. The extraction and purification protocol was per the manufacturer’s instructions. The samples continued through the precipitation step to further concentrate the histones. The final pellet was then resuspended in 50 µl of sterile water for western blots. A NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (ND-2000C, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to quantify the histone yield of each sample. Using the molecular weight and extinction coefficient of core histones (H2B, H3, and H4), the protein concentrations was determined for each sample.

Western blot analysis of histone posttranslational modifications

Following histone purification from control and FTY720-treated MEFs (n = 3 each), Western blots were performed to confirm that the FTY720 treatment increased histone acetylation of the lysine residues reported by Hait et al. (2014). Western blots were performed using Novex 10%–20% Tris-Glycine gels (EC61385Box, Life Technologies; Grand Island, NY), loading 0.5 μg of histone proteins from each sample. The gels were transferred to Immobilon-FL PVDF membranes (IPFL10100, Millipore; Billerica, Massachusetts). When transfer was complete, the membranes were placed in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (927–40000, Li-Cor; Lincoln, Nebraska) for at least 2 h. The membranes were then placed in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies (validated for Western blot and ChIP) included: H2BK12ac (Abcam ab40883; 1:2000), H3K9ac (Qiagen GAM-1209; 1:2000), H3K18ac (Active Motif 39755; 1:1000), H3K23ac (Active Motif 39131; 1:1000), H4K5ac (Cell Signaling 9672; 1:1000), H2B (Active Motif 39210; 1:250), H3 (Qiagen GAM-2206; 1:2000), and H4 (Abcam 10158; 1:1000). A fluorescent goat anti-rabbit 680 LT secondary antibody (Li-Cor 926-68021; 1:20 000) was added to each membrane for 1 h at room temperature, and protein bands were then visualized using an Odyssey 9120 Infrared Imaging System (Li-Cor) and Image Studio (Version 3.1) software.

Statistical analysis

Experiments were done in triplicate and results are expressed as means ± standard error of the means (SEM). For comparison of 2 groups, statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t test. Tests were 2-tailed and differences were considered significant at P value ≤ 0.05. For comparison of multiple groups, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by a Holm-Sidak post hoc test to determine significance (P ≤ .05).

RESULTS

Elevated FTY720 and FTY720-P in the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Compartments of FTY720-Treated LM/Bc MEFs

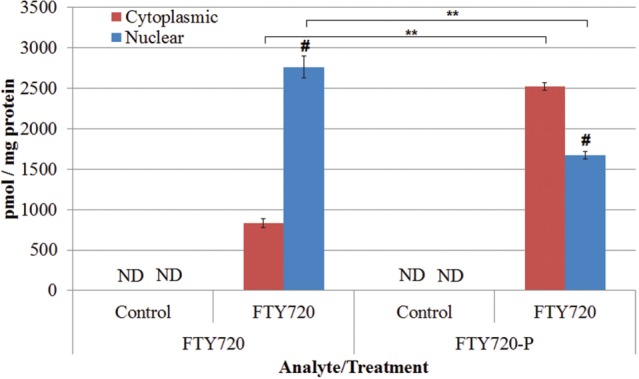

Subcellular localization of FTY720-P was determined by isolating the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from each control and FTY720-treated (1 µM for 24 h) LM/Bc MEF sample (n = 3) using a NE-PER kit. Cell fractions were subsequently analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS for the presence of the parent compound (FTY720) and its phosphorylated metabolite, FTY720-P. FTY720 and FTY720-P were not detected in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus of vehicle control-treated MEFs (Figure 2). However, FTY720 and FTY720-P were detected in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction of cells treated with FTY720 (Figure 2). In LM/Bc MEFs, the parent compound, FTY720, accumulated to a greater extent in the nucleus (2760 ± 139 pmol/mg protein, P = .00021) compared to the cytoplasm (833 ± 54 pmol/mg protein) (Figure 2). FTY720-P, however, was detected at higher concentrations in the cytoplasm of LM/Bc MEFs (2522 ± 46 pmol/mg protein, P = .0002) than in the nucleus (1671 ± 47 pmol/mg protein) (Figure 2). LM/Bc MEFs had significantly more nuclear FTY720 than FTY720-P (P = .0018), but more cytoplasmic FTY720-P than FTY720 (P = .00002). LM/Bc MEFs have been treated with FTY720 and analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS multiple times for multiple purposes, and each time an elevation of FTY720-P is observed (data not shown). The presence of FTY720-P in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions suggests that it may have dual functions, potentially as an HDAC inhibitor (Hait et al., 2014), in addition to its established role as an S1P receptor agonist (Brinkmann et al., 2002; reviewed in Brinkmann, 2007).

FIG. 2.

FTY720 and FTY720-P in LM/Bc MEF cell lines. FTY720 and FTY720-1-P (FTY720-P) were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS/MS in control and FTY720-treated LM/Bc MEFs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent cultures). Neither FTY720 nor FTY720-P was detected in the control samples, verifying that cross contamination did not occur between samples. **The mean level of FTY720 in the cytoplasmic or nuclear fraction of FTY720-treated LM/Bc MEFs is significantly different from FTY720-P in the same fraction (P < .002). # The mean level of FTY720 or FTY720-P in the nuclear fraction of FTY720-treated MEFs is significantly different than the amount of FTY720 or FTY720-P in the cytoplasmic fraction (P = .0002). ND signifies that FTY720 or FTY720-P was not detected in those samples.

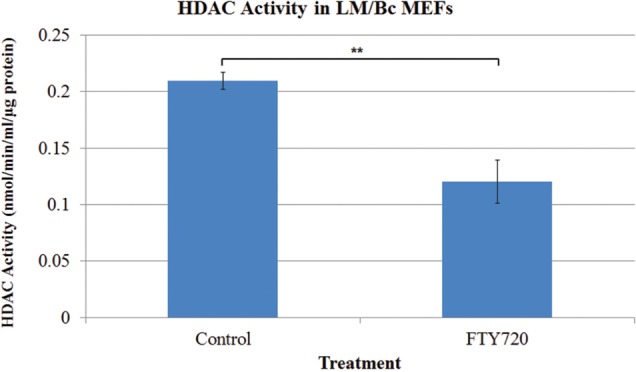

Decreased HDAC in MEFs Treated With FTY720

To determine whether FTY720 treatment and nuclear accumulation of FTY720-P was associated with decreased activity of Class I HDACs, an HDAC activity assay was performed. Nuclear extracts from control and FTY720-treated MEFs were collected and analyzed based on the Cayman HDAC activity protocol. In LM/Bc MEFs, HDAC activity significantly decreased in response to FTY720 treatment (1 µM for 24 h) (control: 0.21 ± 0.008 nmol/min/ml/µg protein; FTY720: 0.12 ± 0.019 nmol/min/ml/µg protein, P = .012) (Figure 3), a result consistent with FTY720-P inhibition of HDACs (Hait et al., 2014).

FIG. 3.

Histone deacetylase activity in nuclear fractions isolated from LM/Bc mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity was measured by a HDAC activity assay, utilizing nuclei of LM/Bc MEFs. Data are shown as mean HDAC activity ± SEM (n = 3). **The mean HDAC activity of the FTY720-treated LM/Bc MEFs is significantly decreased compared to that of the control (vehicle) LM/Bc MEFs (**P < .02).

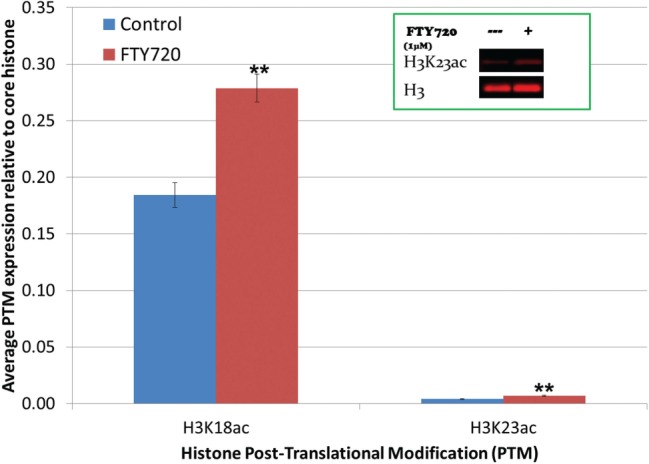

Increased Histone Acetylation in LM/Bc MEFs After FTY720 Treatment

Elevated levels of nuclear FTY720-P and decreased HDAC activity led us to evaluate histone acetylation after FTY720 treatment. LM/Bc MEFs were treated with vehicle-control or 1 µM FTY720 for 24 h. MEFs were then harvested and histones were isolated using a Histone Purification Mini Kit. Specific histone post translational modifications (PTMs) were analyzed by western blots. Because Hait et al. (2014) demonstrated that FTY720-P (generated by overexpression of Sphk2) inhibition of HDACs led to an increase in H2BK12ac, H3K9ac, and H4K5ac in human neuroblastoma cells, these histone PTMs were initially selected for evaluation in MEFs. However, no significant changes in acetylation were observed for these particular lysine residues (H2BK12, H3K9, H4K5) in MEFs treated with FTY720 (data not shown), which could be due to the small sample size and/or differences in cell type. Additional sites of increased histone lysine acetylation (H3K18 and H3K23) that were previously identified in our lab by LC/LC-MS/MS proteomic analysis of control versus FTY720-treated Balb/c serum-free mouse embryonic neural stem cells (submitted) were also evaluated in LM/Bc MEFs by western blots. In this analysis, H3K18ac and H3K23ac (normalized to unmodified H3) were significantly increased in LM/Bc MEFs after FTY720 treatment (P ≤ .008) (Figure 4). Overall, these results suggest that histone PTMs induced by nuclear FTY720-P accumulation and HDAC inhibition may vary with cell type and/or treatment conditions.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of increased histone acetylation in LM/Bc MEFs. LM/Bc mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were treated with vehicle (control) or 1 µM FTY720 for 24 h before being collected using a Histone Purification Mini Kit. Data are shown as mean expression compared to unmodified core histone ± SEM (n = 3). Inset is a visual representative of western blots performed to assess histone acetylation. **The mean histone acetylation expression in treated LM/Bc MEFs is significantly different than that found in LM/Bc control MEFs (**P ≤ .008).

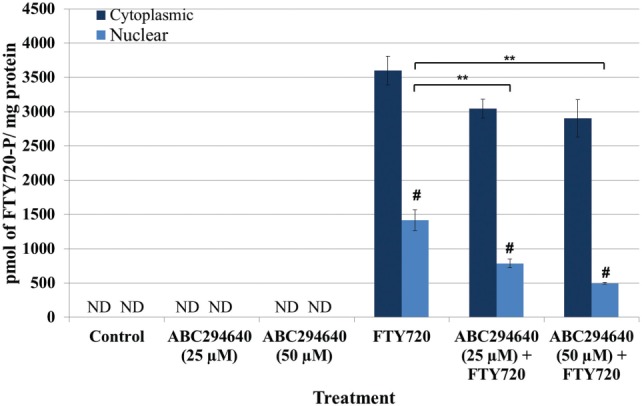

Decreased Nuclear FTY720-P in LM/Bc MEFs Pretreated With ABC294640 and FTY720

In LM/Bc MEFs, FTY720 treatment resulted in increased nuclear FTY720-P (Figure 2), decreased HDAC activity (Figure 3), and increased histone acetylation at H3K18 and H3K23 (Figure 4). Because Sphk2 is more efficient at phosphorylating FTY720 and is predominately located in the nucleus, a Sphk2 selective inhibitor, ABC294640, was tested for its ability to reduce nuclear accumulation of FTY720-P in LM/Bc MEFs. LM/Bc MEFs were pre-treated with 25 µM or 50 µM ABC294640 for 24 h, before a follow-up treatment with 1 µM FTY720 for another 24 h. ABC294640 was present in the cell medium for a total of 48 h and FTY720 for only 24 h. At the end of the 48 h, MEFs were collected for quantification of FTY720-P by LC-ESI-MS/MS. FTY720-P was not detected in vehicle-control or ABC294640 alone treatment, but the expected FTY720-P accumulation was observed in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction (3600 ± 210 pmol/mg protein; 1415 ± 153 pmol/mg protein, respectively) (Figure 5). Pretreatment with ABC294640 did not significantly decrease cytoplasmic FTY720-P, but a slight cytoplasmic decrease was observed at both concentrations. Pretreatment with ABC294640 at both concentrations, however, did significantly reduce nuclear FTY720-P, suggesting that Sphk2 enzymatic activity is primarily nuclear. The 25 µM concentration of ABC294640 resulted in a 44% reduction, with an even stronger reduction (65%) at 50 µM concentration, although no statistical significance between the concentrations was observed. The concentration and/or treatment time used was not able to completely reduce the FTY720-P nuclear accumulation to basal levels.

FIG. 5.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear FTY720-P levels after pre-treatment with ABC294640, a selective Sphk2 inhibitor, followed by FTY720 treatment in LM/Bc MEFs. After treatment(s), MEFs were collected and isolated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions before being analyzed for FTY720-P by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent cultures) and analyzed using an ANOVA, followed by Holm-Sidak post hoc test. Neither FTY720 nor FTY720-P was detected in the control samples, verifying that cross contamination did not occur between samples. **The mean level of nuclear FTY720-P in LM/Bc MEFs treated with ABC294640 and FTY720 was significantly lower than the level found in the nucleus of FTY720-treated MEFs (P ≤ .05). #The mean level of FTY720-P in the nuclear fraction was significantly less than the amount of FTY720-P in the cytoplasmic fraction (P ≤ .0001). ND signifies that FTY720-P was not detected in those samples.

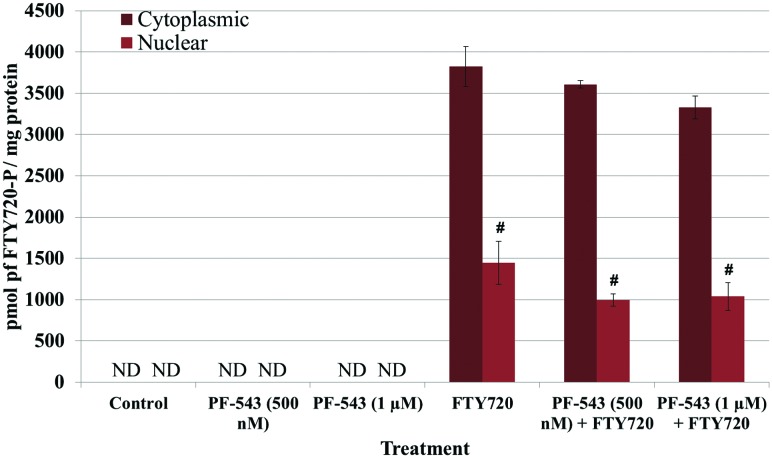

No Reduction in FTY720-P in LM/Bc MEFs Treated With PF-543 and FTY720

Inhibition of Sphk2 was able to decrease nuclear FTY720-P accumulation significantly; however, it did not reduce nuclear FTY720-P levels back to the basal levels observed in control MEFs. To examine whether Sphk1 contributed to the generation of nuclear and/or cytoplasmic FTY720-P, MEFs were treated with the selective Sphk1 inhibitor PF-543. LM/Bc MEFs were simultaneously treated with 500 nM or 1 µM PF-543 and 1 µM FTY720 for 24 h, collected and analyzed for FTY720-P. Once again, FTY720-P was not detected in vehicle-control or PF-543 alone samples (Figure 6). After FTY720 treatment, the expected accumulation of FTY720-P was observed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of LM/Bc MEFs. The inhibitor had no significant effect on the accumulation of FTY720-P in either the cytoplasmic or nuclear fraction. However, a slight reduction in cytoplasmic FTY720-P was observed at 1 µM PF-543. At these concentrations (500 nM or 1 µM) the data do not suggest that Sphk1 plays a major role in the phosphorylation of FTY720.

FIG. 6.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear FTY720-P levels after treatment with PF-543, a selective Sphk1 inhibitor, and FTY720 in LM/Bc MEFs. After treatment(s), MEFs were collected and isolated into cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions before being analyzed for FTY720-P by LC-ESI-MS/MS. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent cultures) and analyzed using an ANOVA, followed by Holm-Sidak post hoc test. Neither FTY720 nor FTY720-P was detected in the control samples, verifying that cross contamination did not occur between samples. #The mean level of FTY720-P in the nuclear fraction was significantly less than the amount of FTY720-P in the cytoplasmic fraction (P ≤ .0001). ND signifies that FTY720-P was not detected in those samples.

DISCUSSION

FTY720-P is more biologically active than FTY720 (Albert et al., 2005), and functions not only as a ligand for S1P receptors (Brinkmann et al., 2002), but also as an HDAC inhibitor (Hait et al., 2014). This study provides novel information on the subcellular generation/accumulation of the bioactive metabolite FTY720-P in an embryonic cell type exposed to FTY720. The goal was to determine the relative amount of FTY720-P that accumulated in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus, and the specific Sphk isoforms involved. The finding that FTY720-P accumulates in both subcellular fractions under normal conditions is novel and suggests that multiple mechanisms may be involved in the biological effects induced by FTY720. This study also demonstrates that nuclear FTY720-P is associated with HDAC inhibition and increased histone acetylation, in agreement with similar findings by Hait et al. (2014), and provides support for potential epigenetic effects of the phosphorylated drug metabolite in addition to its already well-known role as an S1P receptor ligand. The differences in the hyperacetylation of specific lysine residues observed between this study and Hait et al. (2014) may be due to differences in cell type and/or treatment conditions. Alternatively, the relatively small sample size in the MEF study may have precluded detection of significant differences, particularly in the case of H2BK12ac, H3K9ac, and H4K5ac.

While our results, in general, support most of the initial findings by Hait et al. (2014), the cell type and methodology utilized were very different between the 2 studies. This study is the first to report the subcellular localization of FTY720-P in MEFs after treatment with FTY720 in the absence of Sphk2 overexpression. Accumulation of FTY720-P in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus in cells that have not been genetically modified suggests the potential for multiple mechanisms of action for the phosphorylated metabolite under normal conditions, including: (1) as an agonist/functional antagonist for S1P receptors (Brinkmann, 2007; Brinkmann et al., 2002, 2004; Gräler and Goetzl, 2004), and (2) as an HDAC inhibitor (Hait et al., 2014). The biological effects observed in response to FTY720 may therefore be mediated through FTY720-P activation/inhibition of S1P receptor-mediated signaling pathways and/or through HDAC inhibition and epigenetic modifications that alter gene regulation, although it is also possible that alternate, as yet unknown, mechanisms of action for FTY720 and/or FTY720-P exist.

At the highest concentration tested, pretreatment of MEFs with ABC294640, a selective Sphk2 inhibitor, significantly reduced (although did not completely inhibit) formation of FTY720-P in the nuclear fraction. Treatment with a selective Sphk1 inhibitor, PF-543, did not significantly inhibit formation of FTY720-P in either subcellular fraction. The results suggest that Sphk2 is likely the primary kinase responsible for production of FTY720-P in MEFs, although further in vitro experimentation may be necessary to definitively rule out any contribution from Sphk1.

Sphk2 is reportedly the primary kinase involved in phosphorylation of FTY720 (Billich et al., 2003; Paugh et al., 2003), although Hisano et al. (2011) suggest that Sphk1 may also play a role. Targeted disruption of either Sphk1 or Sphk2 in knockout mice produces animals that are viable, fertile, and lack any obvious malformations; however, double knockout mice exhibit abnormalities in neural and vascular development (Mizugishi et al., 2005), which suggests that Sphk1 and Sphk2 may have redundant and/or compensatory functions. Both kinases are expressed in mouse embryonic neuroepithelial tissue; Sphk1/Sphk2 double knockout embryos have undetectable levels of S1P and exhibit cranial NTDs (exencephaly) and impaired neurogenesis (Mizugishi et al., 2005). S1P receptor isoforms are present in human neural progenitor cells (Hurst et al., 2008), and are also differentially expressed in the neural folds and underlying mesenchyme of developing mouse embryos (Meng and Lee, 2009; Ohuchi et al., 2008;). Collectively, these findings implicate a potential role for S1P receptor-mediated signaling in neural tube closure and neurogenesis (Mizugishi et al., 2005).

The current experiments provide evidence of biochemical changes and mechanisms at the cellular level that might contribute to the teratogenicity of FTY720. Our laboratory previously demonstrated that oral administration of FTY720 to pregnant SWV and LM/Bc mice during early gestation results in 40%–60% exencephaly in exposed embryos (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). Elevated levels of FTY720 and FTY720-P were detected in exencephalic embryos, and in maternal blood and plasma (Gelineau-van Waes et al., 2012). In vivo experiments are currently underway to determine if ABC294640 crosses the placenta and if so, to examine whether concurrent treatment of pregnant mice with FTY720 and ABC294640 will inhibit FTY720-P accumulation in embryonic tissue and reduce the incidence of NTDs. One hypothesis concerning gestational exposure to FTY720 and risk for NTDs is that sustained and/or aberrant activation of S1P receptors in the embryo in response to chronically elevated levels of FTY720-P could alter signaling pathways important for neural tube closure. An alternate hypothesis for the induction of NTDs involves HDAC inhibition by elevated levels of nuclear FTY720-P, because the teratogenicity of other known HDAC inhibitors, such as the anticonvulsant drug VPA (Ehlers et al., 1992; Oakeshott and Hunt, 1989; Trotz et al., 1987) and the antifungal antibiotic TSA (Vanhaecke et al., 2004), are well known. Little is known about specific histone PTMs and their relationship to NTDs, although H3K9ac is increased in embryonic stem cells treated with VPA (Hezroni et al., 2011), and both H3K9ac and H3K18ac were increased in amniotic fluid stem cells from an anencephalic pregnancy, but not from normal pregnancies, suggesting these PTMs as possible biomarkers for anencephaly (Tsurubuchi et al., 2013).

Because MS is most prevalent in women of childbearing age (National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 2015a), and because FTY720 can be detected in vivo for approximately 2 months after stopping medication (Karlsson et al., 2014; Novartis, 2014), potential risks to the developing embryo/fetus exist in women taking FTY720 (Gilenya) during pregnancy. A multinational pregnancy registry exists for women taking Gilenya that tracks and monitors the impact of fetal exposure in humans, but further research is needed. Numerous studies are currently underway to identify additional therapeutic applications for FTY720, including the treatment of strokes, Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Rhett disease, epilepsy, and brain tumors (Brunkhorst et al., 2014). As medical applications of FTY720 expand, it will be important to understand all of its potential mechanisms of action and side effects, especially those that could affect embryonic/fetal development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Mark Rainey for the development of the LM/Bc mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Portions of the data in this manuscript were presented at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Teratology Society held in Tucson, Arizona on June 22-26, 2013.

FUNDING

This work was supported by USDA-ARS NP108 in house project (6612-42000-012-00D); Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development & NIH Office of the Director (RC4HD067971); LB692 Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund; and Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services-Division of Public Health Stem Cell Grant (2013-06).

REFERENCES

- Adachi K., Kohara T., Nakao N., Arita M., Chiba K., Mishina T., Sasaki S., Fujita T. (1995). Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationships of 2-substituted-2-amino-1,3-propanediols: Discovery of a novel immunosuppresant, FTY720. Biorg. Org. Med. Chem. Lett. 5,853–856. [Google Scholar]

- Albert R., Hinterding K., Brinkmann V., Guerini D., Müller-Hartwieg C., Knecht H., Simeon C., Streiff M., Wagner T., Welzenbach K., et al. (2005). Novel immunomodulator FTY720 is phosphorylated in rats and humans to form a single stereoisomer. Identification, chemical proof, and biological characterization of the biologically active species and its enantiomer. J. Med. Chem. 48, 5373–5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behjati M., Etemadifar M., Abdar Esfahani M. (2014). Cardiovascular effects of fingolimod: A review article. Iran. J. Neurol. 13, 119–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billich A., Bornancin F., Dévay P., Mechtcheriakova D., Urtz N., Baumruker T. (2003). Phosphorylation of the immunomodulatory drug FTY720 by sphingosine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 47408–47415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V. (2007). Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors in health and disease: Mechanistic insights from gene deletion studies and reverse pharmacology. Pharmacol. Ther. 115, 84–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Cyster J. G., Hla T. (2004). FTY720: Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 in the control of lymphocyte egress and endothelial barrier function. Am. J. Transplant 4, 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Davis M. D., Heise C. E., Albert R., Cottens S., Hof R., Bruns C., Prieschl E., Baumruker T., Hiestand P., et al. (2002). The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 277, 21453–21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V., Pinschewer D., Chiba K., Feng L. (2000). FTY720: A novel transplantation drug that modulates lymphocyte traffic rather than activation. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkhorst R., Vutukuri R., Pfeilschifter W. (2014). Fingolimod for the treatment of neurological diseases-state of play and future perspectives. Front. Cell. Neurosci 8, 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers K., Stürje H., Merker H. J., Nau H. (1992). Valproic acid-induced spina bifida: A mouse model. Teratology 45, 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French K. J., Zhuang Y., Maines L. W., Gao P., Wang W., Beljanski V., Upson J. J., Green C. L., Keller S. N., Smith C. D. (2010). Pharmacology and antitumor activity of ABC294640, a selective inhibitor of sphingosine kinase-2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 333, 129–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelineau-van Waes J., Rainey M. A., Maddox J. R., Voss K. A., Sachs A. J., Gardner N. M., Wilberding J. D., Riley R. T. (2012). Increased sphingoid base-1-phosphates and failure of neural tube closure after exposure to fumonisin or FTY720. Birth Defects Res. A. Clin. Mol. Teratol. 94, 790–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gräler M. H., Goetzl E. J. (2004). The immunosuppressant FTY720 down-regulates sphingosine 1-phosphate G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 18, 551–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hait N. C., Wise L. E., Allegood J. C., O'Brien M., Avni D., Reeves T. M., Knapp P. E., Lu J., Luo C., Miles M. F., et al. (2014). Active, phosphorylated fingolimod inhibits histone deacetylases and facilitates fear extinction memory. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hezroni H., Sailaja B. S., Meshorer E. (2011). Pluripotency-related, valproic acid (VPA)-induced genome-wide histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) acetylation patterns in embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35977–35988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano Y., Kobayashi N., Kawahara A., Yamaguchi A., Nishi T. (2011). The sphingosine 1-phosphate transporter, SPNS2, functions as a transporter of the phosphorylated form of the immunomodulating agent FTY720. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1758–1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst J. H., Mumaw J., Machacek D. W., Sturkie C., Callihan P., Stice S. L., Hooks S. B. (2008). Human neural progenitors express functional lysophospholipid receptors that regulate cell growth and morphology. BMC Neurosci. 9, 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson G., Francis G., Koren G., Heining P., Zhang X., Cohen J. A., Kappos L., Collins W. (2014). Pregnancy outcomes in the clinical development program of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 82, 674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandala S., Hajdu R., Bergstrom J., Quackenbush E., Xie J., Milligan J., Thornton R., Shei G. J., Card D., Keohane C., et al. (2002). Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science 296, 346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechtcheriakova D., Wlachos A., Sobanov J., Bornancin F., Zlabinger G., Baumruker T., Billich A. (2007). FTY720-phosphate is dephosphorylated by lipid phosphate phosphatase 3. FEBS Lett. 581, 3063–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H., Lee V. M. (2009). Differential expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors 1-5 in the developing nervous system. Dev. Dyn. 238, 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizugishi K., Yamashita T., Olivera A., Miller G. F., Spiegel S., Proia R. L. (2005). Essential role for sphingosine kinases in neural and vascular development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 11113–11121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2015a). Pregnancy and Reproductive Issues. Available at: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/Living-Well-With-MS/Family-and-Relationships/Pregnancy, Accessed March 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- National Multiple Sclerosis Society. (2015b). The MS Disease-Modifying Medications. Available at: www.nationalMSsociety.org/DMD, Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Novartis. (2014). Gilenya: Full prescribing information. Available at: https://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gilenya.pdf, Accessed March 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oakeshott P., Hunt G. M. (1989). Valproate and spina bifida. BMJ 298, 1300–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi H., Hamada A., Matsuda H., Takagi A., Tanaka M., Aoki J., Arai H., Noji S. (2008). Expression patterns of the lysophospholipid receptor genes during mouse early development. Dev. Dyn. 237, 3280–3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paugh S. W., Payne S. G., Barbour S. E., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2003). The immunosuppressant FTY720 is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinase type 2. FEBS Lett. 554, 189–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R. T., Plattner R. D. (2000). Fermentation, partial purification, and use of serine palmitoyltransferase inhibitors from Isaria (= Cordyceps) sinclairii. Methods Enzymol. 311, 348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnute M. E., McReynolds M. D., Kasten T., Yates M., Jerome G., Rains J. W., Hall T., Chrencik J., Kraus M., Cronin C. N., et al. (2012). Modulation of cellular S1P levels with a novel, potent and specific inhibitor of sphingosine kinase-1. Biochem. J. 444, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K., Mattsson R., James T. C., Wentzel P., Pilartz M., MacLaughlin J., Miller S. J., Olsson T., Eriksson U. J., Ohlsson R. (1998). The paternal allele of the H19 gene is progressively silenced during early mouse development: The acetylation status of histones may be involved in the generation of variegated expression patterns. Development 125, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotz M., Wegner C., Nau H. (1987). Valproic acid-induced neural tube defects: Reduction by folinic acid in the mouse. Life Sci. 41, 103–110 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsurubuchi T., Ichi S., Shim K. W., Norkett W., Allender E., Mania-Farnell B., Tomita T., McLone D. G., Ginsberg N., Mayanil C. S. (2013). Amniotic fluid and serum biomarkers from women with neural tube defect-affected pregnancies: A case study for myelomeningocele and anencephaly: Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr .12, 380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaecke T., Papeleu P., Elaut G., Rogiers V. (2004). Trichostatin A-like hydroxamate histone deacetylase inhibitors as therapeutic agents: Toxicological point of view. Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 1629–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltse J. (2005). Mode of action: Inhibition of histone deacetylase, altering WNT-dependent gene expression, and regulation of beta-catenin–developmental effects of valproic acid. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 35, 727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka M., Anada Y., Igarashi Y., Kihara A. (2008). A splicing isoform of LPP1, LPP1a, exhibits high phosphatase activity toward FTY720 phosphate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 375, 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitomer N. C., Glenn A. E., Bacon C. W., Riley R. T. (2008). A single extraction method for the analysis by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry of fumonisins and biomarkers of disrupted sphingolipid metabolism in tissues of maize seedlings. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 391, 2257–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitomer N. C., Mitchell T., Voss K. A., Bondy G. S., Pruett S. T., Garnier-Amblard E. C., Liebeskind L. S., Park H., Wang E., Sullards M. C., et al. (2009). Ceramide synthase inhibition by fumonisin B1 causes accumulation of 1-deoxysphinganine: A novel category of bioactive 1-deoxysphingoid bases and 1-deoxydihydroceramides biosynthesized by mammalian cell lines and animals. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4786–4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]