Abstract

Background

The fatty acid profile is associated with the risk and progression of several diseases, probably via mechanisms including its influence on gene expression. We previously reported a correlation between ECHDC3 upregulation and the severity of acute coronary syndrome. Here, we assessed the relationship of serum fatty acid profile and ECHDC3 expression with the extent of coronary lesion.

Methods

Fifty-nine individuals aged 30 to 74 years and undergoing elective cinecoronariography for the first time were enrolled in the present study. The extent of coronary lesion was assessed by the Friesinger index and patients were classified as without lesion (n = 18), low lesion (n = 17), intermediate lesion (n = 17) and major lesion (n = 7). Serum biochemistry, fatty acid concentration, and ECHDC3 mRNA expression in blood were evaluated.

Results

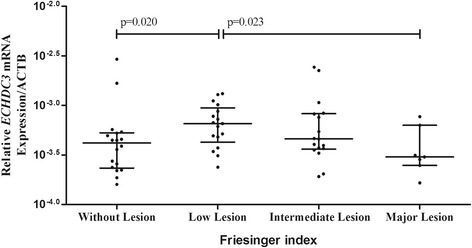

Elevated serum levels of oleic acid and total monounsaturated fatty acids were observed in patients with low and intermediate lesion, when compared to patients without lesion (p < 0.05). ECHDC3 mRNA expression was 1.2 fold higher in patients with low lesion than in patients without lesion (p = 0.020), and 1.8 fold lower in patients with major lesion patients than in patients with low lesion (p = 0.023).

Conclusion

Increased levels of monounsaturated fatty acids, especially oleic acid, and ECHDC3 upregulation in patients with coronary artery lesion suggests that these are independent factors associated with the initial progression of cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Oleic acid, ECHDC3, Friesinger index, Monounsaturated fatty acids, Cardiovascular diseases

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide. The early diagnosis of CVD along with proper assessment of cardiovascular risk is crucial for further reduction of health care costs and mortality rates. Knowledge of the CVD physiopathology seems to be the best approach to achieve these goals. ‘Omics’ analysis can contribute to this field by providing fundamental information to better understand complex biological systems, such as atherosclerosis [1], the primary origin of most common cardiovascular disorders [2].

Particularly, transcriptomics is a relevant tool for the identification of diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers for CVD. In a microarray-based gene expression study performed previously by our research team, we found that ECHDC3 mRNA expression was significantly increased within 2 h after an acute coronary syndrome, suggesting this gene could be a potential novel biomarker for the early stage of an acute episode [3]. However, the function of ECHDC3 or its involvement with cardiovascular diseases is scarcely explored in the literature, which might be due to its recent identification. ECHDC3 encodes enoyl-CoA hydratase domain containing 3, a mitochondrial enzyme that has a crotonase-like domain similar to enoyl-CoA hydratase [4]. Furthermore, ECHDC3 is presumed to be involved in β-oxidation, the most important and well-known pathway for fatty acid (FA) oxidation [5–7].

The consumption of specific dietary FAs has been shown to influence risk and progression of several chronic diseases, such as CVD, possibly by altering gene expression [8, 9]. However, studies in this field have provided ambiguous results, especially regarding the effects of monounsaturated FAs (MUFAs) on risk for coronary heart disease [10]. Since there is no study evaluating the relationship between FA levels and genes related to CVD development and progression yet, we aimed to evaluate the serum FA profile and ECHDC3 expression in patients with varying extent of coronary lesion.

Methods

Study population

Fifty-nine male and female individuals aged between 30 to 74 years that were undergoing cinecoronariography to investigate extent of coronary lesion were enrolled in the present study. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, heart valve disease, congenital diseases, pericarditis, coronary revascularization, chronic kidney disease, liver failure, endocrine disorder (except for diabetes mellitus), inflammatory diseases, malignant diseases, blood disorders, autoimmune diseases and family history of hypercholesterolemia. Patients were selected at the Hemodynamics unit of Hospital Universitário Onofre Lopes. This study was approved by the hospital’s Research Ethics Committee under protocol number CAAE 0001.0.051.294-11. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Blood samples and biochemical analysis

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from patients. Fasting serum glucose, total cholesterol and fractions, urea, creatinine K, uric acid, alanine and aspartate aminotransaminases were measured using colorimetric and colorimetric-enzymatic methods in BIO-2000 IL, a semi-automatic biochemical analyzer (Bioplus, São Paulo, Brazil). Values of LDL-cholesterol were calculated according to the Friedewald formula [11].

Extent of coronary lesion

The extent of coronary lesion was assessed by the Friesinger index [12, 13]. Each of the three main coronary arteries (anterior descending, circumflex and right coronary) was scored separately from zero to five. Subjects were classified as without lesion when the Friesinger index was equal to 0; low lesion, when it varied from 1 to 5; intermediate lesion, 6–10; and major lesion, 11–15, as adapted from Chagas et al. (2013) [14].

Gas chromatography

Total serum lipids were extracted using a mixture of methanol and chloroform chromatographic solution (2:1, vol/vol), and FAs were converted to FA methyl esters using a modified sodium methoxide method [15]. Then the FA profile was estimated using flame-ionization gas chromatography on a device (CG-2010, SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a DB-FFAP capillary column (15 m × 0.100 mm × 0.10 μm [J&W Scientific from Agilent Technologies, Folsom, CA, USA]). Individual peaks were quantified as the area under the peak and results expressed as percentages of the total area of all FA peaks [16].

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from blood samples previously stored in RNAlater® Stabilization Solution (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), using an RiboPureTM – Blood kit (Life Technologies). RNA integrity was assessed by 1 % agarose gel electrophoresis with MOPS buffer, while its quantity was measured using Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies). cDNA synthesis was performed using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) in a MyCycler Thermal Cycler (BIO-RAD, Philadelphia, PA, USA). RT-qPCR was performed using ECHDC3 TaqMan Assay (Hs00226727_m1) (Life Technologies). The reference gene was selected from a normalization study of three endogenous candidate genes: GAPDH (Hs.592355), ACTB (Hs.520640), and 18S rRNA (Hs.626362). RT-qPCR reactions were carried out in 96-well plates using the 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression of ECHDC3 was calculated using the 2-deltaCT method [17] with ACTB as a reference gene.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® 22.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Normal distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables with normal distribution are presented as mean and standard deviation and were compared using ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. Variables with skewed distributions are presented as median and interquartile range and were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann-Whitney’s test. Categorical variables were compared by chi-square test. Spearman and Pearson correlations were performed between all continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05.

Results

According to the Friesinger index, the patients were classified into four groups: without lesion (n = 18), low lesion (n = 17), intermediate lesion (n = 17), and major lesion (n = 7). Demographic, anthropometric, clinical, and biochemical data of these groups are shown in Table 1. We did not find significant differences among the groups regarding clinical and biochemical data.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric and clinical data of patients classified according to the extent of coronary lesion

| Variables | Total (n = 59) | Without lesion (n = 18) | Low lesion (n = 17) | Intermediate lesion (n = 17) |

Major lesion (n = 7) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.0 ± 9.0 | 55.0 ± 9.0 | 62.0 ± 9.0 | 63.0 ± 10 | 60.0 ± 7.0 | 0.080 |

| Sex male, % | 54.2 | 44.4 | 58.8 | 64.7 | 42.9 | 0.582 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.82 ± 5.65 | 27.86 ± 4.70 | 25.27 ± 8.52 | 26.92 ± 4.29 | 27.43 ± 1.13 | 0.630 |

| Obesity, % | 20.3 | 33.3 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 0 | 0.133 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 91.5 | 77.8 | 100.0 | 94.1 | 100.0 | 0.080 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 30,5 | 33.3 | 23.5 | 35.3 | 28.6 | 0.884 |

| Hypertension, % | 79.7 | 77.8 | 76.5 | 82.4 | 85.7 | 0.944 |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg | 84.0 ± 20.0 | 81.0 ± 8.0 | 80.0 ± 24.0 | 90.0 ± 18.0 | 90.0 ± 32.0 | 0.355 |

| Systolic pressure, mmHg | 143.0 ± 26.0 | 137.0 ± 24.0 | 139.0 ± 22.0 | 155.0 ± 32.0 | 141.0 ± 21.0 | 0.187 |

| Alcoholism, % | 18.6 | 27.8 | 17.6 | 5.9 | 28.6 | 0.350 |

| Smoking, % | 22.0 | 27.8 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 28.6 | 0.825 |

| Physical activity, % | 47.5 | 50.0 | 58.8 | 35.3 | 42.9 | 0.573 |

| Biochemical Analyses | ||||||

| Glucose, mmol/l | 5.16 (3.72–21.87) | 4.75 (3.89–14.26) | 4.88 (3.75–11.04) | 5.55 (3.72–21.87) | 5.94 (4.44–13.04) | 0.443 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | 4.61 (2.95–7.85) | 4.36 (3.08–6.50) | 4.51 (3.19–6.89) | 5.05 (2.95–7.85) | 4.61(3.65–7.02) | 0.555 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mmol/l | 0.92 (0.41–1.45) | 0.95 (0.57–1.45) | 0.93 (0.54–1.30) | 0.91 (0.41–1.32) | 0.83 (0.62–1.40) | 0.669 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mmol/l | 2.68 (1.21–5.74) | 2.38(1.49–4.57) | 2.63(1.21–5.00) | 3.26 (1.21–5.74) | 2.89 (1.93–5.27) | 0.419 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/l | 1.62 (0.75–9.47) | 1.63 (0.79–6.94) | 2.25(0.86–6.96) | 1.62(0.75–9.47) | 1.45 (0.85–3.24) | 0.612 |

| ALT, μKat/l | 0.43 (0.17–2.19) | 0.38 (0.17–1.57) | 0.43 (0.25–1.04) | 0.33 (0.17–2.19) | 0.60 (0.25–1.45) | 0.723 |

| AST, μKat/l | 0.52 (0.25–1.57) | 0.52 (0.25–1.49) | 0.43 (0.25–0.95) | 0.52 (0.25–1.57) | 0.60 (0.25–1.57) | 0.546 |

| Ureia, mmol/l | 5.85 (3.34–10.35) | 5.93 (3.34–9.52) | 5.68 (4.31–9.85) | 5.93(3.37–10.35) | 5.85 (4.84–6.35) | 0.693 |

| Creatinine, μmol/l | 79.56 (17.68–141.44) | 79.56 (53.04–141.44) | 79.56(53.04–123.76) | 88.40 (53.04–106.08) | 70.72 (17.68–106.08) | 0.323 |

| Uric acid, mmol/l | 0.29 (0.11–0.52) | 0.27(0.16–0.52) | 0.28 (0.11–0.43) | 0.29 (0.11–0.43) | 0.33 (0.14–0.37) | 0.965 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation for parametric samples and as median (interquartile range) for non-parametric samples. Categorical variables were compared by Chi-square test. Parametric analysis was performed by ANOVA way. Non-parametric samples were performed by Kruskal-Wallis test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all statistical test. BMI body mass index, HDL-cholesterol high density lipoprotein, LDL-cholesterol low density lipoprotein, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine transaminase

FA serum concentrations of the different groups are shown in Table 2. Patients with low and intermediate lesion presented higher concentrations of oleic acid (p = 0.025 and p = 0.034, respectively) compared to patients without lesion. Similarly, MUFA levels were higher in patients with low and intermediate lesion (p = 0.023 and p = 0.040, respectively) than in patients without lesion. We did not observe significant changes in other FAs among the groups.

Table 2.

Serum fatty acid concentration according to the extent of coronary lesion

| Fatty acids (%) | Total (n = 59) | Without lesion (n = 18) | Low lesion (n = 17) | Intermediate lesion (n = 17) | Major lesion (n = 7) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFA | 44.12 ± 3.85 | 44.70 ± 4.18 | 43.79 ± 4.46 | 43.93 ± 2.74 | 43.93 ± 4.40 | 0.904 |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 0.89 ± 0.30 | 0.94 ± 0.36 | 0.91 ± 0.26 | 0.87 ± 0.31 | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 0.756 |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 30.83 ± 3.07 | 31.40 ± 2.95 | 30.61 ± 3.15 | 30.52 ± 2.80 | 30.63 ± 4.22 | 0.830 |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 12.40 ± 1.89 | 12.36 ± 2.15 | 12.27 ± 2.10 | 12.54 ± 1.70 | 12.50 ± 1.30 | 0.979 |

| MUFA | 24.87 ± 3.10 | 23.66 ± 2.88 | 25.97 ± 2.84a | 25.77 ± 2.96b | 23.14 ± 3.35 | 0.032 |

| Palmitoleic (C16:1) | 2.55 ± 0.75 | 2.41 ± 0.62 | 2.73 ± .63 | 2.56 ± 0.89 | 2.47 ± 0.98 | 0.658 |

| Oleic (C18:1) | 22.32 ± 2.77 | 21.25 ± 2.54 | 23.24 ± 2.48c | 23.22 ± 2.73d | 20.66 ± 2.89 | 0.027 |

| PUFA | 31.01 ± 4.78 | 31.65 ± 4.46 | 30.24 ± 5.37 | 30.30 ± 3.99 | 32.94 ± 6.01 | 0.529 |

| n-6 | 26.77 ± 4.29 | 27.26 ± 3.66 | 25.96 ± 5.13 | 26.46 ± 3.54 | 28.26 ± 5.53 | 0.628 |

| Linoleic (C18:2) | 18.06 ± 3.84 | 18.64 ± 3.29 | 17.23 ± 4.35 | 18.10 ± 3.30 | 18.47 ± 5.39 | 0.742 |

| Arachidonic (C20:4) | 8.71 ± 2.37 | 8.62 ± 1.73 | 8.73 ± 2.47 | 8.36 ± 2.20 | 9.78 ± 3.89 | 0.620 |

| n-3 | 4.23 ± 1.17 | 4.38 ± 1.56 | 4.29 ± 1.02 | 3.84 ± 0.86 | 4.68 ± 0.91 | 0.363 |

| a-linolenic (C18:3) | 0.54 ± 0.20 | 0.56 ± 0.20 | 0.53 ± 0.21 | 0.52 ± 0.16 | 0.57 ± 0.31 | 0.916 |

| EPA (C20:5) | 0.46 ± 0.18 | 0.53 ± 0.24 | 0.42 ± 0.15 | 0.43 ± 0.16 | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 0.223 |

| DPA (C22:5) | 0.83 ± 0.23 | 0.83 ± 0.21 | 0.86 ± 0.17 | 0.80 ± 0.28 | 0.85 ± 0.33 | 0.891 |

| DHA (C22:6) | 2.39 ± 0.93 | 2.46 ± 1.26 | 2.48 ± 0.82 | 2.10 ± 0.67 | 2.74 ± 0.73 | 0.410 |

| n-6/n-3 | 6.77 ± 2.12 | 6.80 ± 1.93 | 6.61 ± 2.96 | 7.14 ± 1.63 | 6.16 ± 1.29 | 0.765 |

| SCD16 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.398 |

| SCD18 | 1.85 ± 0.40 | 1.77 ± 0.38 | 1.95 ± 0.38 | 1.90 ± 0.45 | 1.68 ± 0.36 | 0.376 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons were performed by ANOVA way test followed by test t between pairs. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant for all statistical test

EPA, eicosapentaenoic, DHA docosahexaenoic, DPA docosapentaenoic SFA saturated fatty acid, MUFA monounsaturated fatty acid, PUFA polyunsaturated fatty acid, n6 omega-6, n3 omega-3, SCD16 stearoyl-CoA-Desaturase 16, SCD18, stearoyl-CoA-Desaturase 18

a p = 0.023 for comparison between low lesion vs. without lesion groups by test t

b p = 0.040 for comparison between intermediate lesion vs. without lesion groups by test t

c p = 0.025 comparison between low lesion vs. without lesion groups by test t

d p = 0.034 for comparison between intermediate lesion vs. without lesion groups by test t

Regarding mRNA relative expression (Fig. 1), ECHDC3 mRNA expression were 1.2-fold higher in patients with low lesion than in patients without lesion (p = 0.020), and 1.8-fold lower in patients with major lesion than in patients with low lesion (p = 0.023).

Fig. 1.

ECHDC3 mRNA expression relative to ACTB expression according to the extent of coronary lesion. Data are presented as median and interquartile range. Relative expression of ECHDC3 was calculated using the 2-deltaCT method. Statically analysis was performed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Mann Whitney test

Pearson analysis showed a positive correlation between oleic acid with triglyceride levels (r = 0.397, p = 0.002), MUFA (r = 0.974, p < 0.001), SCD16 (r = 0.352, p = 0.006) and SCD18 (r = 0.751, p < 0.001). ECHDC3 gene expression positively correlated with SFA (r = 0.259, p = 0.048) and negatively correlated with SCD16 (r = −0.289, p = 0.027).

Discussion

In the present study, all patients under CVD risk were classified according to the presence and extent of coronary lesion. Higher levels of MUFA, mainly oleic acid, and ECHDC3 upregulation were found in patients with low coronary lesion when compared to those without coronary lesion, however we did not find significant difference between patients with major lesions and those without coronary lesion. These findings suggest that both observed high oleic acid levels and ECHDC3 upregulation may induce initial events of the atherosclerotic process. There is a large number of growth factors, cytokines, regulatory molecules and different cell types that are involved in atherosclerosis development, each having a different function [18]. Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis differ throughout the stages of disease, and a factor that is important to the initial stage might not be relevant in the late stage, supporting our results.

Oleic acid is an abundant monounsaturated omega-9 fatty acid that affects different biological processes, and is associated with increased expression of genes linked to FA oxidation [19]. These genes are reported to be altered during specific disease conditions that impact the heart, including cardiac failure, myocardial ischemia, and diabetes [20]. In the present study, a positive correlation between oleic acid and triglycerides levels was observed in patients with cardiac lesion, suggesting that there is a potential influence of this FA on the increase of CVD risk. This is supported by a study performed in healthy individuals of both genders showing that virgin olive oil consumption, a oleic acid-rich food, led to upregulation of many genes associated with atherosclerosis disease [21]. Moreover, in cultures of rat aortic smooth muscle cells, the treatment with oleic acid was associated with cell lipid accumulation, increasing foam cell formation in a dose-dependent manner [22].

It was previously reported that ECHDC3 mRNA expression was significantly increased in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction when compared to unstable angina, indicating its association with the severity of CVD [3]. The ECHDC3 role in CVD is scarcely explored to allow a more comparative discussion of our data, but is known that ECHDC2 upregulation in cardiac tissue of rats was related to increased susceptibility to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury [23]. ECHDC3 shares 30 % identity with ECHDC2 [24], and these proteins may possibly have similar functions in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. In addition, both proteins are named after enoyl-CoA hydratase, an essential enzyme for the β-oxidation of FAs, because they share a conserved domain [7, 23]. The potential involvement of ECHDC3 in β-oxidation of FA pathway led us to investigate the possible correlation between changes of FA profile and this gene expression.

The high serum levels of oleic acid presently observed might be due to stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) activity, as this fatty acid presented a positive correlation with SCD16 and SCD18 levels. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) catalyzes a rate-limiting step in the unsaturated FA synthesis, which main product is oleic acid [25]. Notably, SCD has been associated with inflammatory cluster [16] and metabolic syndrome, reinforcing the impression of a detrimental association of oleic acid levels and CVD risk [26].

We do recognize some limitations of our study: the diet of individuals was not studied, and the sample size is small. However, to the best our knowledge, it is the first study evaluating the relationship between ECHDC3 mRNA expression and FA levels in patients classified according to the Friesinger index.

Conclusion

Our data suggests that increased oleic acid levels and ECHDC3 upregulation in individuals with coronary artery lesion could be independent factors associated to the early CVD development. More investigation is needed to validate this hypothesis and to consider whether the monitoring of FA serum levels, especially the oleic acid, would be valuable for the assessment of cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgments

A.A.F. Carioca is recipient of fellowships from FAPESP, Brazil. V.H.R. Duarte and R.H. Bortolin are recipients of fellowships from CAPES, Brazil.

Funding

This study was supported financially by grants from FAPERN (Number 005/2011) and CNPQ (Number 483031/2013-5).

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

VNS and ADL were responsible for original concept of the study and study design; MKRND, JNGA, KMO and VHRD were responsible for recruitment of the patients; MKRND, DLW, JNGA, KMO and VHRD performed the laboratory analysis; MKRND, JMO, AAFC, DLW, JNGA, RHB, VNS and ADL interpreted the results and performed the statistical analyses; MKRND, JNGA, RHB, VNS and ADL wrote the manuscript; AUR, RDCH, MHH, DLW, SCVC, ADL and VNS were responsible for critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the hospital’s Research Ethics Committee under protocol number CAAE 0001.0.051.294-11. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Abbreviations

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DHA

Docosahexaenoic

- DPA

Docosapentaenoic

- EPA

Eicosapentaenoic

- FA

Fatty acid

- MUFA

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- n3

Omega-3

- n6

Omega-6

- PUFA

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SFA

Saturated fatty acid.

Contributor Information

Mychelle Kytchia Rodrigues Nunes Duarte, Email: mychellekytchia@hotmail.com.

Jéssica Nayara Góes de Araújo, Email: jessnaysub@hotmail.com.

Victor Hugo Rezende Duarte, Email: victor_15rd@hotmail.com.

Katiene Macêdo de Oliveira, Email: katienemacedo12@gmail.com.

Juliana Marinho de Oliveira, Email: juliana.marinho07@gmail.com.

Antonio Augusto Ferreira Carioca, Email: aafc7@hotmail.com.

Raul Hernandes Bortolin, Email: raulhbortolin@yahoo.com.br.

Adriana Augusto Rezende, Email: adrirezende@yahoo.com.

Mario Hiroyuki Hirata, Email: mhhirata@usp.br.

Rosário Domingues Hirata, Email: rosariohirata@usp.br.

Dan Linetzky Waitzberg, Email: dan.waitzberg@gmail.com.

Severina Carla Vieira Cunha Lima, Email: scvclima@gmail.com.

André Ducati Luchessi, Email: andre.luchessi@outlook.com.

Vivian Nogueira Silbiger, Email: viviansilbiger@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Siemelink MA, Zeller T. Biomarkers of coronary artery disease: the promise of the transcriptome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16:513. doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husain K, Hernandez W, Ansari RA, Ferder L. Inflammation, oxidative stress and renin angiotensin system in atherosclerosis. World J Biol Chem. 2015;6:209. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v6.i3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silbiger VN, Luchessi AD, Hirata RDC, Lima-Neto LG, Cavichioli D, Carracedo A, et al. Novel genes detected by transcriptional profiling from whole-blood cells in patients with early onset of acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;421:184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desikan RS, Schork AJ, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Dehghan A, Ridker PM, et al. Polygenic overlap between C-reactive protein, plasma lipids, and Alzheimer disease. Circulation. 2015;131:2061–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miura Y. The biological significance of ω-oxidation of fatty acids. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2013;89:370–82. doi: 10.2183/pjab.89.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linster CL, Noël G, Stroobant V, Vertommen D, Vincent MF, Bommer GT, et al. Ethylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase, a new enzyme involved in metabolite proofreading. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42992–3003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Ibrahim MM, Sun M, Tang J. Enoyl-coenzyme A hydratase in cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;448:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Georgiadi A, Kersten S. Mechanisms of gene regulation by fatty acids. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:127–34. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kersten S. Effects of fatty acids on gene expression: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, liver X receptor alpha and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. Proc Nutr Soc. 2002;61:371–4. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Monounsaturated fatty acids and risk of cardiovascular disease: synopsis of the evidence available from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutrients. 2012;4:1989–2007. doi: 10.3390/nu4121989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringqvist I, Fisher LD, Mock M, Davis KB, Wedel H, Chaitman BR, et al. Prognostic value of angiographic indices of coronary artery disease from the coronary artery surgery study (CASS) J Clin Invest. 1983;71:1854–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI110941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bampi ABA, Rochitte CE, Favarato D, Lemos PA, da Luz PL. Comparison of non-invasive methods for the detection of coronary atherosclerosis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64:675–82. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000700012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chagas P, Caramori P, Galdino TP, De Barcellos CDS, Gomes I, Schwanke CHA. Egg consumption and coronary atherosclerotic burden. Atherosclerosis. 2013;229:381–4. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang Z, Wang B, Crenshaw AA. A simple method for the analysis of trans fatty acid with GC–MS and ATTM-Silar-90 capillary column. Food Chem. 2006;98:593–8. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oki E, Norde MM, Carioca AAF, Ikeda RE, Souza JMP, Castro IA, et al. Interaction of SNP in the CRP gene and plasma fatty acid profile in inflammatory pattern: a cross-sectional population-based study. Nutrition. 2016;32:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ÄÄCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Yao H, Hui J-Y, Ding S-H, Fan Y-L, Pan Y-H, et al. Global transcriptomic study of atherosclerosis development in rats. Gene. 2016;592:43–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim J-H, Gerhart-Hines Z, Dominy JE, Lee Y, Kim S, Tabata M, et al. Oleic acid stimulates complete oxidation of fatty acids through protein kinase A-dependent activation of SIRT1-PGC1α complex. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7117–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.415729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Georgiadi A, Boekschoten MV, Müller M, Kersten S. Detailed transcriptomics analysis of the effect of dietary fatty acids on gene expression in the heart. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:352–61. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00115.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khymenets O, Fitó M, Covas M-I, Farré M, Pujadas M-A, Muñoz D, et al. Mononuclear cell transcriptome response after sustained virgin olive oil consumption in humans: an exploratory nutrigenomics study. OMICS. 2009;13:7–19. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma S, Yang D, Li D, Tang B, Yang Y. Oleic acid induces smooth muscle foam cell formation and enhances atherosclerotic lesion development via CD36. Lipids Heal Dis. 2011;10:53. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du J, Li Z, Li Q-Z, Guan T, Yang Q, Xu H, et al. Enoyl coenzyme A hydratase domain-containing 2, a potential novel regulator of myocardial ischemia injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000233. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Protein BLAST. http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE=Proteins. Accessed 1 May 2016.

- 25.Liu X, Strable MS, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl CoA desaturase 1: role in cellular inflammation and stress. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:15–22. doi: 10.3945/an.110.000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayneris-Perxachs J, Guerendiain M, Castellote AI, Estruch R, Covas MI, Fitó M, et al. Plasma fatty acid composition, estimated desaturase activities, and their relation with the metabolic syndrome in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the corresponding author.