Abstract

Introduction:

Bronchopneumonia is the most common clinical manifestation of pneumonia in pediatric population and leading infectious cause of mortality in children under 5 years. Evaluation of treatment involves diagnostic procedures, assessment of disease severity and treatment for disease with an emphasis on vulnerability of the population.

Aim:

To determine the most commonly used antibiotics at the Pediatric Clinic in Sarajevo and concomitant therapy in the treatment of bronchopneumonia.

Patients and Methods:

The study was retrospective and included a total of 104 patients, hospitalized in pulmonary department of the Pediatric Clinic in the period from July to December 2014. The treatment of bronchopneumonia at the Pediatric Clinic was empirical and it conformed to the guidelines and recommendations of British Thoracic Society.

Results and Discussion:

First and third generation of cephalosporins and penicillin antibiotics were the most widely used antimicrobials, with parenteral route of administration and average duration of treatment of 4.3 days. Concomitant therapy included antipyretics, corticosteroids, leukotriene antagonists, agonists of β2 adrenergic receptor. In addition to pharmacotherapy, hospitalized patients were subjected to a diet with controlled intake of sodium, which included probiotic-rich foods and adequate hydration. Recommendations for further antimicrobial treatment include oral administration of first-generation cephalosporins and penicillin antibiotics.

Conclusion:

Results of the drug treatment of bronchopneumonia at the Pediatric Clinic of the University Clinical Center of Sarajevo are comparable to the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society. It is necessary to establish a system for rational use of antimicrobial agents in order to reduce bacterial resistance.

Keywords: bronchopneumonia, pediatric population, drug therapy, diagnostic procedures, clinical features

1. INTRODUCTION

Bronchopneumonia is the most common clinical manifestation of pneumonia in pediatric population. It is a leading infective cause of mortality in children under 5 years of age. In 2013, bronchopneumonia caused death in 935,000 of children under 5 years. Etiological causative agents of bronchopneumonia are bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi. Since pediatric population is vulnerable and specific, clinical features are often non-specific and conditioned by numerous factors. These factors include certain age group, presence of comorbidity, exposure to risk factors, carried out immunization etc.

The most reliable way to diagnose bronchopneumonia is through chest X-ray, but that is not enough to determine the ethiological agent, so the treatment of bronchopneumonia is clinical rather than ethiological in most cases. Since bronchopneumonia is an infectious disease, antimicrobic agents must be used in the treatment, along with additional supportive and symptomatic treatment.

However, frequent use of antibiotics leads to a rise in bacterial resistance (1). Bacterial resistance, along with limitations in establishment of timely diagnosis and difficult ethiological classification, often leads to severe clinical features and inadequate response to therapy, which results in increased number of treatment days, as well as increased consumption of antimicrobials.

The aim of this study was to determine the most often proscribed antibiotics and supporting concomitant therapy in treatment for bronchopneumonia at the Pediatric Clinic in Sarajevo, and to determine whether the treatment is in accordance with the British Thoracic Society guidelines.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included patients under 18 with diagnosis of bronchopneumonia, patients with detailed history of the disease and detailed information on diagnostics and treatment carried out at the Pediatric Clinic, and patients who were hospitalized in the pulmonary department in the period from 1st July to 31st December 2014. Analysis results are displayed in tables and graphs as per number of cases, percentage, and arithmetic mean (X) with standard deviation (SD), standard error (SE) and a range of values (min-max.). Testing of differences between age groups was performed using Wilcoxon signed rank test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with significance level of p <0.05 which was considered to be statistically significant. The analysis was performed using statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics v 21.0.

3. RESULTS

The study included 104 patients who met criteria for enrollment. In the total sample, there was a higher number of male subjects (60 or 57.7%) than female patients (44 or 42.3%). According to the formed age groups, the highest number of patients was in the preschool and school age groups (39 patients each or 37.5%), followed by the age group of infants (22 or 21.2%). Age groups of newborns and adolescents included 2 patients each or 1.9%. Average age in sample was 55.3±43.3 months. The youngest patient was 1 month old and the oldest was 192 months old (16 years).

According to the data in patient’s history, some of the symptoms were dominant in clinical features. Cough was present in 88 or 84.6% of patients, with average body temperature of 38.7±0.9; 37-40.2 oC. Chest pain was experienced by 66 or 63.5% of patients, and vomiting was experienced by 64 or 64.5% of patients. Duration of hospital stay (number of days of hospitalization) averaged 5.2±2.6 days, with shortest stay of 1 day and longest stay of 15 days. Out of total number of subjects, 66 or 63.5% were immunized regularly. In the period of the study (July-December), readmission to hospital due to bronchopneumonia was recorded in 12 subjects or 11.5%.

Average oxygenation level was 90.3±0. 6, and ranged from 74.4 to 97.2%. The largest number of patients–67 of them (64.2%)–had three dominant symptoms in clinical features. Ten patients (9.61%) had 4 or more symptoms. In newborn and infant age group, the following symptoms prevailed: cough, increased body temperature, and vomiting. In preschool children age group, cough was present in 87.18%, increased body temperature in 97.44%, chest pain in 66.67%, and vomiting in 41.03 % of the subjects. In school children age group, cough as a symptom was present in 79.49 %, increased body temperature in 94.87%, chest pain in 94.87 %, and vomiting in 7.69 % of the subjects. In adolescent age group, cough, chest pain and increased body temperature were present in all subjects, while vomiting was not observed at all.

Upon admission, CRP was elevated in 100% of newborns and adolescents, in 81.82% of infants, 79.49% of preschoolers, and in 92.31% of school-age children. Upon admission, white blood cell count was elevated in 50% of newborns, 72.73% of infants, 71.79% of preschoolers, 58.97% of school-age children and in 100% of adolescents.

Used antibiotic therapy

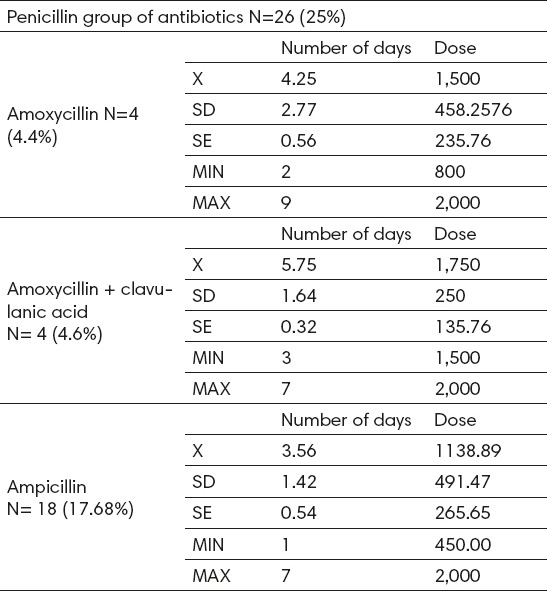

Penicillin antibiotics were administered intravenously to 26 (25%) subjects. Within this group, the most widely used medicine was ampicillin (17.68%), with an average dose of 1138.89 ± 491 mg (450- 2000), and the average duration of therapy 3.56 ± 1.42 days (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analysis of use of penicillin group of antibiotics

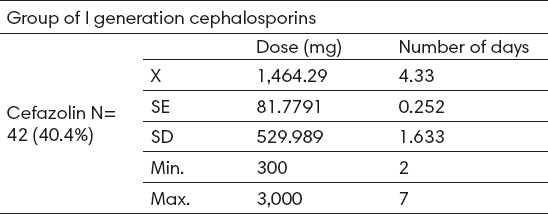

First-generation cephalosporins were administered to 42 patients (40.4%), intravenously in all cases. The only medicine in this group that was administered was cefazolin with average dose of 1,464.3 ± 530 mg (300-3000) and average treatment duration of 4.3 ± 1.6 days (2-7). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of use of the I generation cephalosporin

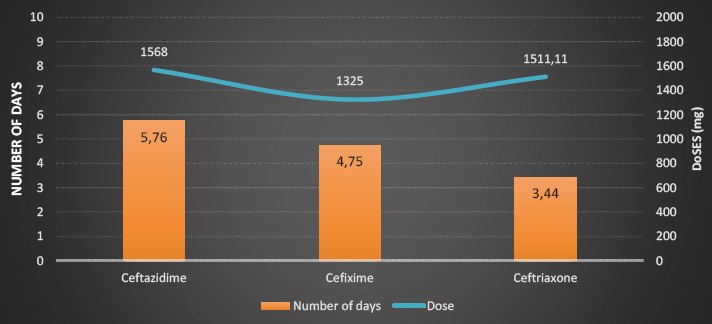

Third-generation cephalosporins were administered to 33 or 31.7% subjects (intravenously in all cases). The most often used drug in this group was ceftazidime with an average dose of 1568 ± 585.34 mg (250-2400), and the average duration of therapy was 5.76 ± 2.62 days (Figure 1).

Figure. 1.

Analysis of use of the III generation cephalosporins

Total duration of the antibiotic therapy averaged 4.5 ± 1.9 days and ranged from 1 to 11 days.

Recommended therapy for treatment continuation

Medicines from the group of penicillins were recommended for continuation of treatment of 28 patients (26.9%). The most commonly recommended medication in the aforementioned group was ampicillin in two forms (suspension and tablets). The average dose of ampicillin was 11.2 ± 4.59 ml in form of suspension and 1.160 ± 634.35 mg as tablet.

Drugs in cephalosporins group were recommended in total of 61 subjects (73.1%). The most recommended medication in this group was cefixime, with an average recommended daily dose of 8.74 ± 4.78 ml in the form of a suspension and 828.57 ± 455.8 mg in the form of tablets (Table 3). Among other drugs recommended for treatment continuation at home, antipyretics were recommended in 54 or 51.9% of cases, methylprednisolone in 53 or 51% of the cases, and montelukast in 75 or 72.1% of cases.

4. DISCUSSION

We present the results of 104 patients who were hospitalized at pulmology department of the Pediatric Clinic with diagnosis of bronchopneumonia. According to the results of our study we recommend oral administration of first-generation cephalosporins and penicillin antibiotics as effective treatment for bronchopneumonia in the pediatric population.

In the last 30 years, a lot of research has been done with the purpose of achieving a more effective treatment of bronchopneumonia in the pediatric population and a reduction in bronchopneumonia-caused mortality. The turning point was year 1985 when the World Health Organization undertook activities to establish a unified strategy to combat pneumonia worldwide (1).

The Pediatric Clinic of the University Clinical Center of Sarajevo has also based its principles of treating bronchopneumonia on observing guidelines and protocols, as well as principles of good clinical practice. Hence the usual empirical treatment is based on proven connection of certain causative agents with specific populations, while etiological treatment is very rare. A study done on 385 hospitalized children in Africa in 2014 found that there is a very low risk of failure when using drugs mentioned in the guidelines and protocols relative to the targeted etiological treatment (0.37 (95% CI -0.84 to 0.51)(2).

According to the research done by the World Health Organization, for quality management of bronchopneumonia, certain criteria must be met in order to refer a child to hospital treatment: a child with persistent high body temperature or fever should be considered as a potential pneumonia patient; if symptoms persist or if there is no response to treatment prescribed by pediatricians or family doctors, it is necessary to reassess and to consider the gravity of the clinical situation; children with less than 92% oxygen saturation or children who show severe signs of respiratory distress should be hospitalized; auscultatory absence of respiratory sounds and dull sound on percussion indicate the possibility of pneumonia with complications and can be used as an indication for hospital admission; children with elevated parameters of acute inflammation; children under 6 months of age with signs of disease and children with poor general health (3).

Treatment of bronchopneumonia involves administration of medicines and use of high calorie dietary regimes with adequate hydration. Pharmacological measures imply administration of antimicrobial and concomitant therapy. Antimicrobials used in the treatment of bronchopneumonia are first and third generation of cephalosporins, as well as penicillin based antibiotics. In our study, antibiotic therapy lasted 4.5 ± 1.9 days on average and ranged from 1 to 11 days.

Cefazolin in the group of first-generation cephalosporins was administered in 42 patients, or in 40.4% of all subjects. In all patients, cefazolin was administered intravenously at a dose of 1,464.3 ± 530 mg (900-3,000) and the average duration of treatment was 4.3 ± 1.6 days

Third-generation cephalosporins have been administered intravenously to 33 patients, or 31.7%. The most commonly used medicine in the group of third-generation cephalosporins was ceftazidime. A total of 17 subjects in the treatment received ceftazidime, the lowest dose was given in infants (900 mg) and the highest dose was given to school-aged children (2,400 mg). The average duration of treatment with ceftazidime was 5.3 ± 2.1 days.

Penicillin antibiotics were exclusively intravenously administered in 26 patients (25%). Ampicillin as the most often used drug from the penicillin group was administered in 18 patients with an average dose of 1,173.1 ± 500 mg (450-2,000) and the average treatment duration of 3.96 ± 2 days. Shortest duration of therapy has been recorded in the penicillin group of antibiotics. Studies in India from 2013, conducted on a total of 1,116 children at the pediatric departments in 20 hospitals, showed that the treatment with penicillin antibiotics is more effective in comparison to treatment with other antibiotics (4).

Study showed that the second and third generation of cephalosporins were used in infants, but not in adolescents. In the treatment of children of preschool age, first-generation cephalosporins were most often used, while third-generation cephalosporins were most often used in school-aged children. In determination of difference in the use of antibiotic therapy in relation to age of patients, statistically significant difference was only demonstrated in the use of penicillin antibiotics (p <0.05). According to the dose of administered antibiotic, it has been shown that dose increases linearly with age, with the lowest dose administered in infants. A significant difference was observed only in patients to whom cefazolin and ceftriaxone were administered (p <0.05).

There were no statistically significant differences in average duration of treatment in relation to age group (in all <0.05), but still there were some noticeable differences. Duration of treatment with third-generation cephalosporins was longest in infants (7 days) and shortest in children of preschool age (4.7 days).

According to the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society, certain guidelines should be adhered to during treatment of bronchopneumonia. Every child with a clear diagnosis of pneumonia should receive antibiotic therapy since it is not possible to make immediate reliable differentiation of bacterial and viral pathogens (5). Intravenous administration of antibiotics is recommended for children suffering from pneumonia in cases when a child cannot tolerate oral intake of drugs or their absorption (i.e. due to vomiting), and also for hospitalized children with more severe clinical features (6).

Recommended intravenous antibiotics for treatment of severe bronchopneumonia are: amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav, cefuroxime and cefotaxime or ceftriaxone. Use of these antibiotics can be rationalized if microbiological diagnostics is performed (7).

It is advisable to consider oral administration of medicines in patients to whom antibiotics were administered intravenously and who subsequently experienced noticeable improvement in clinical features (8). American Thoracic Society recommends the so-called “switch” therapy, which implies switching from parenteral to oral antibiotics. The main problem is the lack of clear definition of the moment or conditions when the patient should make the switch to oral administration (9). Orally administered antibiotics and concomitant therapy are recommended for continuation of treatment, and than can be considered as a variant of the “switch” therapy.

Studies conducted in Italy in 2012, showed that intravenous administration of antimicrobials has several far-reaching effects on pediatric patients and treatment itself (10). In the opinion of child psychologists, parenteral route of administration is considered to be traumatic for the child, with more rapid appearance of adverse effects (11).

Studies of the American Thoracic Society from 2013 indicated that patients with respiratory disease should have a specific diet rich in minerals and vitamins with a moderate amount of easily digestible proteins, poor in carbohydrates and rich in fat (12). Important aspects in the treatment of child bronchopneumonia are rest and adequate hydration.

It is necessary to work on prevention in order to reduce the incidence of morbidity. Studies conducted in UK in 2003 showed that introduction of vaccination revolutionized prevention of infectious diseases. It has been shown that introduction of vaccines against measles reduced incidence of mortality by 2.5 million a year.

Studies conducted in the United States in the period 2009-2013 have shown that introduction of the conjugate vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae would make the biggest advance in prevention of pneumonia, since it is the most common etiologic agent of this type of pneumonia. Controlled study with use of WHO standardization of radiographic definition of pneumonia included 37,868 children.

Vaccination effectiveness of 30.3% (95% CI 10.7% to 45.7%, p¼0.0043) has been observed in the study, taking into account age, sex and year of vaccination. During this four-year program implemented in the entire country, the incidence of disease was reduced by 39% (26 children) in children under 2 years of age. Italian single-blind study from 2012 showed that there was a statistically significant difference in occurrence of bronchopneumonia in children who are not immunized compared to those who are (13).

According to study conducted on patients hospitalized at the pulmonary department of the Pediatric clinic, 38 patients (37%) did not receive immunization regularly.

Increase in use of third-generation cephalosporins, and aminopenicillins is a cause for concern. Since such increase is also observed in vulnerable pediatric population, current situation must be analyzed and restrictive-educational measures ought to be recommended based on results of such analysis. Hence the use of antibiotics would be rationalized (14).

Study results showed that Pediatric clinic has access to modern diagnostic tests, the treatment is carried out in accordance with the protocols and guidelines, which largely correspond to the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society. The latest antimicrobials and concomitant therapy for treatment are available.

5. CONCLUSION

The study shows that the results of bronchopneumonia treatment at the Pediatric Clinic of the University Clinical Center of Sarajevo are comparable to the results of other studies that were conducted at Pediatric clinics.

First and third generation cephalosporins (cephazolin and ceftriaxone, respectively) and penicillin antibiotics (ampicillin) were most commonly used antimicrobial agents with the average duration of antibiotic therapy of 4.3 days, all of which is consistent with the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society.

Concomitant therapy usually consisted of antipyretics (diclofenac and paracetamol), β2 adrenergic receptor agonist (salbutamol), leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast), and corticosteroids (methylprednisolone).

Availability and performance of diagnostic tests, as well as pharmacological measures conform to the guidelines of the British Thoracic Society.

For the purpose of preventing bronchopneumonia in pediatric population, specific epidemiological measures ought to be taken, and they should involve all levels of health care. Awareness of early signs and symptoms of bronchopneumonia should be raised in the population, and especially parents, in order to begin treatment a timely manner. To reduce the incidence of disease, introduction of the pneumococcal vaccination must be considered, as pneumococcal infection is the leading cause of bronchopneumonia.

Footnotes

• Conflict of interest: None

• Author’s contribution: Svjetlana Loga Zec, Kenan Selmanovic made substantial contribution to conception, design, drafting the article and critical revision for important intellectual content. Natasa Loga Andrijic and Azra Kadic made substantial contribution to acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision for important intellectual content. Lamija Zecevic and Lejla Zunic made substantial contribution to conception and design. All the authors approved the final version to be published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cizman M. The use and resistance to antibiotics in the community. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agweyu A, Kibore M, Digolo L, Kosgei C, Maina V, Mugane S, Muma S, Wachira J, Waiyego M, Maleche-Obimbo E. Prevalence and correlates of treatment failure among Kenyan children hospitalised with severe community-acquired pneumonia:a prospective study of the clinical effectiveness of WHO pneumonia case management guidelines. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(11):1310–20. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, Alverson B, Carter ER, Harrison C, Kaplan SL, Mace SE, McCracken GH, Jr, Moore MR, St Peter SD, Stockwell JA, Swanson JT. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Executive summary:the management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age:clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):617–30. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabra SK, Lodha R, Pandey RM. Antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD004874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004874.pub2. Update in:Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 6:CD004874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harris JA. Antimicrobial therapy of pneumonia in infants and children. Semin Respir Infect. 1996;11(3):139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lodha R, Kabra SK, Pandey RM. Antibiotics for community-acquired pneumonia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD004874. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004874.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toska A, Geitona M. Antibiotic resistance and irrational prescribing in paediatric clinics in Greece. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(1):28–33. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leekha S, Terrell CL, Edson RS. General principles of antimicrobial therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(2):156–67. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rooshenas L, Wood F, Brookes-Howell L, Evans MR, Butler CC. The influence of children’s day care on antibiotic seeking:a mixed methods study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(622):e302–12. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X679741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muszynski JA, Knatz NL, Sargel CL, Fernandez SA, Marquardt DJ, Hall MW. Timing of correct parenteral antibiotic initiation and outcomes from severe bacterial community-acquired pneumonia in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(4):295–301. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ff64ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chetty K, Thomson AH. Management of community-acquired pneumonia in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2007;9(6):401–11. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200709060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wonodi CB, Deloria-Knoll M, Feikin DR, DeLuca AN, Driscoll AJ, Moïsi JC, Johnson HL, Murdoch DR, O’Brien KL, Levine OS, Scott JA. Pneumonia Methods Working Group and PERCH Site Investigators. Evaluation of risk factors for severe pneumonia in children:the Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 2):S124–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Principi N, Esposito S. Efficacy of the heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine against meningitis, pneumonia and acute otitis media in pediatric age. Theoretical coverage offered by the heptavalent conjugate vaccine in Italy. Ann Ig. 2002;14(6 Suppl 7):21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junuzovic Dz, Zunic L, Dervisefendic M, Skopljak A, Pasagic A, Masic I. The Toxic Efect on Leukocyte Lineage of Antimicrobial Therapy in Urinary and Respiratory Infections. Med Arch. 2014 Jun;68(3):167–9. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2014.68.167-169. doi:10.5455/medarh2014.68.167-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]