Abstract

Components of fish roe possess antioxidant and antiaging activities, making them potentially very beneficial natural resources. Here, we investigated chum salmon eggs (CSEs) as a source of active ingredients, including vitamins, unsaturated fatty acids, and proteins. We incubated human dermal fibroblast cultures for 48 hours with high and low concentrations of CSE extracts and analyzed changes in gene expression. Cells treated with CSE extract showed concentration-dependent upregulation of collagen type I genes and of multiple antioxidative genes, including OXR1, TXNRD1, and PRDX family genes. We further conducted in silico phylogenetic footprinting analysis of promoter regions. These results suggested that transcription factors such as acute myeloid leukemia-1a and cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein may be involved in the observed upregulation of antioxidative genes. Our results support the idea that CSEs are strong candidate sources of antioxidant materials and cosmeceutically effective ingredients.

Keywords: fish egg, antiaging, gene expression analysis, antioxidative gene, phylogenetic footprinting analysis

Introduction

Skin is the body’s largest organ, representing the interface between self and nonself. Skin aging is most prominently caused by extrinsic factors, mainly the permanent exposure of this organ to oxidative environmental stimuli, such as solar radiation, cigarette smoke, and other pollutants.1 The second most important contributor to skin aging is an intrinsic factor: the age-related mitochondrial enzyme dysfunction that inhibits epidermal regeneration.2

In the field of cosmetic science, skin aging is clinically characterized by water loss, reduced skin thickness, sagging, and wrinkle formation.3 At the molecular level, skin aging is characterized by reduced procollagen synthesis4–6 and degradation of the extracellular matrix,7 which mainly comprises collagen, glycosaminoglycan, and elastin. Aged skin fibroblasts become detached from the destabilized extracellular matrix, leading to a rounded and collapsed appearance. This in turn upregulates matrix metalloproteinase expression, activating a positive-feedback loop that further accelerates collagen matrix degradation.8 Based on evidence that oxidative stress plays pivotal roles in both intrinsic and extrinsic aging, it has been suggested that antioxidants may be an efficient means of defense against aging processes.9–11

Numerous studies have examined compounds derived from marine and botanical organisms that show cosmetically useful antioxidant and antiaging activities.12,13 Fish roe is a potential source of antiaging material, as it contains vitamins, proteins, unsaturated fatty acids, etc.14 In a previous study, Marotta et al15 demonstrated that nutraceuticals derived from beluga sturgeon’s caviar (containing DNA, collagen elastin, and protein) robustly promoted the expression of collagen type I following in vitro supplementation.

In this study, we investigated the cosmetic use of chum salmon eggs (CSEs), called “Ikura” in Japanese. Differentiating them from other fish eggs, CSEs exhibit high concentrations of proteins (27%–35% of total weight) and crude lipids (12%–20%), with 30% of the total lipids comprising phospholipids and 63% triglycerides. CSEs also show high content of vitamin A (50–3,000 IU/g),14 which is one of the most popular skin aging treatments.16 The xanthophyll carotenoid astaxanthin is the major contributor to the deep yellow-orange color of the muscle of salmon and is also found in CSEs. Astaxanthin is the precursor of vitamin A17 and per se quenches free radicals without being destroyed or becoming a pro-oxidant in the process.18 Using a repeated insult patch test, randomized clinical trials have shown improvements in several important parameters for perception of skin facial health and aging, following treatment with extract from eggs of Atlantic salmon19 (belongs to the same Salmonidae family as chum salmon). However, the effectiveness of CSEs in vitro has not yet been ascertained.

Here, we tested the efficacy of CSE extract using collagen synthesis ability as a measure of skin rejuvenation capacity. We also examined the alterations of gene expression related to oxidative stress response and reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism.

Materials and methods

Salmon egg extract preparation

The ethics committee of Yokohama City University does not require approval to be sought for experiments with commercial cells. Raw CSEs (purchased online) were homogenized using the TissueRuptor rotor-stator device (Qiagen NV, Venlo, the Netherlands) and were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline to a concentration of 105 mg/L. This solution was centrifuged at 1,200 rpm for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.22 µm filter. CSE solutions were stored at −80°C and, once thawed, were either used up or discarded.

Cell culture

Normal human neonatal skin fibroblasts (NB1RGB cells) were purchased from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Ibaraki, Japan). These cells were cultured in α-MEM medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), penicillin 100 U/mL, and streptomycin 2.5 µL/mL. Cells were plated at a concentration of 1×105 cells/dish (100 mm φ), and the plates were supplemented with CSE solution at 80 µg/mL or 800 µg/mL or with phosphate-buffered saline as a negative control. Each experimental condition was replicated two times.

After incubation for 48 hours at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2, total RNA was isolated from fibroblasts using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted RNA was stored at −80°C.

Gene expression assay

Reverse transcription of total RNA was conducted using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the product was stored at 4°C. Quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of the collagen 1A1 and 1A2 genes was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with TaqMan gene expression assays. Relative quantification of gene expression was accomplished using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene as an endogenous control.

Oxidative stress analysis PCR array

After confirming the fold changes of collagen genes, we assessed the total antioxidant profile of the cells using Human Oxidative Stress RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen NV), which contains 84 key genes related to the oxidative stress response. All reactions were carried out using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Relative expression values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Genes with low absolute expression levels were excluded from further analyses, and the cut-off was set at 35 Ct.

All values from both the TaqMan assay and PCR array experiments are presented as the arithmetic means of two biological replicates.

Promoter analysis in silico

We performed transcription regulation analysis of 33 genes related to the oxidative stress response with fold changes over the defined threshold (induced) and of 31 genes with expression changes below the threshold (uninduced) in the 800 µg/mL CSE condition. The Sequence Homology in Higher Eukaryotes (in preparation) tool was used to perform the comparative genome promoter analysis in the human, mouse, and rat genome.20 We used sequences to 5,000 nucleotides upstream and 200 nucleotides downstream from the transcriptional start sites referenced in the DBTSS database.21 Analysis included the following steps:20 1) pairwise (human–mouse and human–rat) alignment (≥50% similarity); 2) multiple alignment of human, mouse, and rat promoters; 3) computing the multiple alignment score22 for alignments conserved among three species in order to assign the strength of the identified orthologous alignment compared to a nonorthologous alignment; 4) scoring the human sequence with publicly available Transfac23 matrices; and 5) selecting the best scoring motifs using the Pareto front method.24 Additionally, we compared the transcription factor frequencies using the motif conservation score25 for the induced gene set and for the uninduced gene set. Finally, transcription factors with motif conservation score ≥10 were chosen as candidates for the transcription regulation of CSE-induced oxidative stress genes.

Composition analysis of CSEs

In order to presume what triggered observed changes involving multiple genes and transcription factors, we conducted a content analysis of CSEs, which was outsourced to a specialized institution, Japan Food Research Laboratories (Tokyo, Japan). The content of protein was quantified by the Kjeldahl method, and the total lipid content was measured by the acid hydrolysis method. The quantities of vitamin A, vitamin E, and astaxanthin were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method.

Results

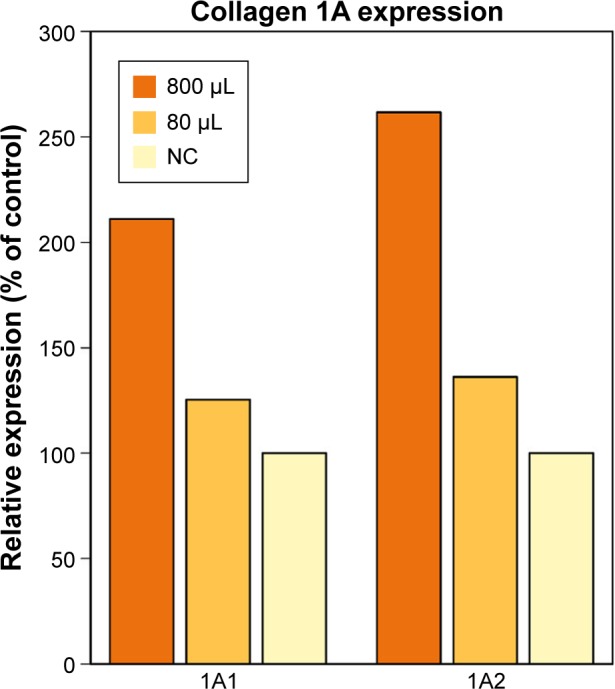

TaqMan assay revealed that supplementation with CSE extracts led to concentration-dependent upregulation of collagen type I mRNA expression (Figure 1). COL1A1 expression was 125% of the control expression level with CSEs of 80 µg/mL and 211% with CSEs of 800 µg/mL. Similarly, COL1A2 expression was 136% of the control expression level with CSEs of 80 µg/mL and 262% with CSEs of 800 µg/mL.

Figure 1.

Expression of collagen type I gene with CSE extract supplementation relative to negative control.

Abbreviations: CSEs, chum salmon eggs; NC, negative control.

Oxidative stress PCR array analysis

Analysis of the oxidative stress pathway with the RT2 Profiler PCR Array revealed that 64 of the 84 genes were expressed in all samples, and we were able to obtain their meaningful relative expression values. To define a “prominent” increase or decrease in gene expression, we set the fold-change threshold to ±2. Table 1 lists the genes showing prominent up- or down-regulation, excluding those with low absolute expression levels, ie, for which the average threshold cycle is relatively high (>30) in the control, 80 µg/mL, or 800 µg/mL condition. We found upregulation of many genes related to the oxidative stress response, with the greatest fold change observed for the peroxiredoxin family genes (PRDX3, PRDX4, and PRDX5), thioredoxin (TXN) reductase 1 (TXNRD1), and oxidation resistance 1 (OXR1). We also observed notably high fold changes of PRDX1 (24.88 with 80 µg/mL and 3.01 with 800 µg/mL); however, it was omitted from Table 1 due to its relatively low absolute expression levels.

Table 1.

Differentially regulated genes involved in oxidative resistance and reactive oxygen species metabolism

| Gene | Description | Fold change

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 80 µg/mL | 800 µg/mL | ||

| SCARA3 | Scavenger receptor class A, member 3 | −1.88 | −5.29 |

| DUSP1 | Dual specificity phosphatase 1 | −2.69 | 1.33 |

| AOX1 | Aldehyde oxidase 1 | −1.89 | −2.65 |

| VIMP | Selenoprotein S | −1.87 | −2.65 |

| GSTP1 | Glutathione S-transferase pi 1 | 1.07 | 2.12 |

| HSPA1A | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1A | 2.13 | 1.06 |

| PXDN | Peroxidasin homolog (Drosophila) | 2.14 | 1.52 |

| GCLM | Glutamate-cysteube ligase, catalytic subunit | 1.89 | 2.14 |

| MGST3 | Microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 | 1.52 | 2.16 |

| TXN | Thioredoxin | 1.09 | 2.19 |

| FTH1 | Ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 | −1.32 | 4.25 |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1 | 2.13 | 4.28 |

| HMOX1 | Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 1.84 | 4.39 |

| SRXN | Sulfiredoxin 1 | 4.41 | 8.75 |

| RNF7 | Ring finger protein 7 | 3.10 | 4.42 |

| PRDX3 | Peroxiredoxin 3 | 8.52 | 4.22 |

| TXNRD1 | Thioredoxin reductase 1 | 6.13 | 12.36 |

| PRDX4 | Peroxiredoxin 4 | 17.55 | 17.50 |

| PRDX5 | Peroxiredoxin 5 | 17.69 | 12.60 |

| OXR1 | Oxidation resistance 1 | 24.87 | 17.72 |

Note: The values above 2.0 or below −2.0 are shown in bold.

The peroxiredoxin system and the glutathione peroxidase (GPX) system are the two main sets of oxidative stress response genes. Compared to the peroxiredoxin system genes, GPX system genes showed less prominent relative expressions, with most genes showing a change of only −1.5- to 1.5-fold. No GPXs (GPX1–GPX7) were highly upregulated, but several glutathione-related genes were prominently upregulated with 800 µg/mL CSEs, including MGST3 (2.16-fold), GCLM (2.14-fold), and GSTP1 (2.12-fold).

Other major ROS metabolism genes, including catalase and superoxide dismutases (SOD1–SOD3), also did not exhibit prominent upregulation. SOD3 showed upregulated expression (2.15 in 80 µg/mL and 1.52 in 800 µg/mL), but its absolute expression was below the criteria for inclusion in Table 1.

The other prominently increased genes showed diverse primary roles, including peroxidase activity (PXDN), stabilizing proteins against aggregation (HSPA1A), iron storage (FTH), reduction of antioxidant molecules (NQO1), and antioxidant molecule preparation (HMOX1). However, each of these genes is directly or indirectly involved in the antioxidative status of the cell.

Promoter analysis in silico

Table 2 presents the transcription factor-binding motifs that are evolutionarily conserved and that showed >50% similarity to the consensus sequence. We identified 16 such transcription factors, nine of which are described in this section.

Table 2.

Transcription factors (16)

| TF name | PSSM | Consensus | MCS | Positive | Control | Gene | Location | Motif |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-Myc:Max | M00322 | GCCAYGYGSN | 46.83 | 3[8] | 0[0] | PRDX4 | [46–55] | CCCACGTGGC [0.65] (14) |

| PRDX4 | [260–269] | CCCACGTGGC [0.65] (14) | ||||||

| GCLM | [782–791] | GCCGCGCGCT [0.65] (15) | ||||||

| ATF | M00017 | CNSTGACGTNNNYC | 29.21 | 2[5] | 0[0] | DUSP1 | [125–136] | GGGTGACGTCAC [0.54] (2) |

| NF-E2 | M00037 | TGCTGAGTCAY | 23.33 | 3[4] | 0[0] | FTH1 | [252–262] | TGCTGAGTCAC [0.95] (8) |

| HMOX1 | [115–125] | TGCTGAGTCAC [0.95] (8) | ||||||

| SQSTM1 | [172–182] | TGCTGAGTCAT [0.95] (13) | ||||||

| SQSTM1 | [19–29] | TGCTGAGTCAC [0.95] (27) | ||||||

| SREBP-1 | M00220 | NATCACGTGAY | 23.33 | 3[4] | 0[0] | FOXM1 | [62–72] | CGTCACGTGAC [0.77] (3) |

| SQSTM1 | [440–450] | GACCACCTGAC [0.68] (11) | ||||||

| USF | M00187 | GYCACGTGNC | 22.59 | 5[25] | 1[1] | GCLC | [66–75] | GTCACGTGGC [0.85] (19) |

| PRDX4 | [46–55] | CCCACGTGGC [0.75] (26) | ||||||

| PRDX4 | [260–269] | CCCACGTGGC [0.75] (26) | ||||||

| PRDX4 | [46–55] | CCCACGTGGC [0.75] (28) | ||||||

| PRDX4 | [260–269] | CCCACGTGGC [0.75] (28) | ||||||

| AP-1 | M00517 | NNNTGAGTCAKCN | 17.46 | 2[3] | 0[0] | SQSTM1 | [19–31] | TGCTGAGTCACGC [0.54] (21) |

| FTH1 | [252–264] | TGCTGAGTCACGG [0.54] (28) | ||||||

| CREBATF | M00981 | NTGACGTNA | 17.46 | 2[3] | 0[0] | DUSP1 | [127–135] | GTGACGTCA [0.78] (9) |

| SIRT2 | [437–445] | GTGACGTAG [0.67] (21) | ||||||

| CREB | M00801 | CGTCAN | 14.37 | 8[33] | 4[4] | PRDX4 | [571–576] | CGTCAG [0.83] (4) |

| DUSP1 | [131–136] | CGTCAC [0.83] (10) | ||||||

| FOXM1 | [62–67] | CGTCAC [0.83] (10) | ||||||

| SIRT2 | [1,002–1,007] | CGTCAC [0.83] (10) | ||||||

| HMOX1 | [55–60] | CGTCAT [0.83] (26) | ||||||

| TXNRD2 | [296–301] | CGTCAG [0.83] (26) | ||||||

| DUSP1 | [142–147] | CGTCAC [0.83] (27) | ||||||

| NRSF | M00325 | TTYAGCWCCDCGGASAGYRCC | 11.58 | 2[2] | 0[0] | PRDX3 | [71–91] | CTCCGAGCGTCGGTGAGTGGC [0.54] (17) |

| EGR1 | M00243 | WTGCGTGGGCGK | 11.58 | 2[2] | 0[0] | PRDX5 | [1,559–1,570] | ATGCGTGGGAGG [0.83] (8) |

| TXN | [219–230] | CTGCCTGGGCGG [0.79] (30) | ||||||

| PRDX5 | [2,973–2,982] | ACCGGAAGTG [0.9] (28) | ||||||

| ELK1 | M00025 | NNNNCCGGAARTNN | 11.58 | 2[2] | 0[0] | PRDX5 | [2,970–2,983] | AGAACCGGAAGTGG [0.54] (18) |

| NRF2 | M00821 | NTGCTGAGTCAKN | 11.58 | 2[2] | 0[0] | SQSTM1 | [18–30] | CTGCTGAGTCACG [0.77] (12) |

| CRE-BP1 | M00179 | VGTGACGTMACN | 11.58 | 1[2] | 0[0] | DUSP1 | [126–137] + | GGTGACGTCACC [0.82] (4) |

| DUSP1 | [126–137] − | GGTGACGTCACC [0.82] (4) | ||||||

| CRE-BP1:c-Jun | M00041 | TGACGTYA | 11.58 | 1[2] | 0[0] | DUSP1 | [128–135] + | TGACGTCA [0.94] (1) |

| DUSP1 | [128–135] − | TGACGTCA [0.94] (1) | ||||||

| DEC | M00997 | SCCCAMGTGAAGN | 11.58 | 1[2] | 0[0] | PRDX4 | [45–57] | GCCCACGTGGCGG [0.69] (20) |

| PRDX4 | [259–271] | GCCCACGTGGCGG [0.69] (20) | ||||||

| AML-1a | M00271 | TGTGGT | 10.29 | 12[33] | 7[20] | GPX1 | [203–208] | TGCGGT [0.83] (3) |

| PRDX3 | [6–11] + | TGTGGT [1] (3) | ||||||

| PRDX3 | [6–11] − | TGTGGT [1] (3) | ||||||

| GPX1 | [692–697] | TGTGGT [1] (3) | ||||||

| PRDX5 | [153–158] | TGTGGT [1] (8) | ||||||

| PRDX3 | [43–48] | TGTGGT [1] (9) | ||||||

| GCLC | [281–286] | TGTGGT [1] (11) | ||||||

| TXNRD1 | [427–432] | TGTGGT [1] (18) | ||||||

| PRDX1 | [49–54] | TGTGGT [1] (19) | ||||||

| GCLC | [128–133] | TGTGGT [1] (20) | ||||||

| GSTP1 | [15–20] | TGTGGT [1] (23) | ||||||

| PRDX3 | [18–23] | TGTGGT [1] (24) | ||||||

| GSTP1 | [28–33] | TGTGGT [1] (25) |

Notes: Columns are as follows: PSSM, matrix number in public Transfac database; consensus, motif consensus using International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nucleotide ambiguity codes (http://www.bioinformatics.org/sms/iupac.html); positive, unique number of genes (out of the 33 induced genes) with the respective motif and the number of motif copies in brackets; control, unique number of genes (out of the 31 uninduced genes) with the respective motif and the number of motif copies in brackets; gene, selected genes from the positive set; location, location in the promoter toward the transcriptional start site, with a +/− indication when the motif is on the reverse or complement strand; motif, motif sequence identified, matching score to the consensus in square brackets, and the number of the Pareto front in parentheses.

Abbreviations: AML-1a, acute myeloid leukemia-1a; CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein; MCS, motif conservation score; TF, transcription factor.

The promoters of several induced genes included transcription factors of acute myeloid leukemia-1a (AML-1a), which is involved in the anti-inflammatory response,26 and of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB), which is involved in hyaluronic acid synthesis27 and in regulating development, stress, and inflammatory pathways in fibroblasts.28

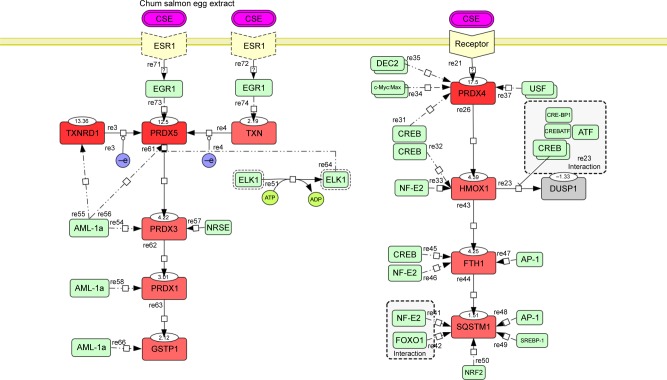

The PRDX5, PRDX3, PRDX1, and GCTP1 genes shared the AML-1a transcription factor-binding motif. The PRDX4, HMOX1, FTH1, and DUSP1 genes shared the CREB transcription factor-binding motif. As an example, Figure S1 shows the CREB identified in the orthologous promoters of the PRDX4 gene in humans, mice, and rats. Based on the motifs shared by the promoters, we created a hypothetical map of the transcriptional regulation using the CellDesigner software (Figure 2).29

Figure 2.

Hypothetical map of transcription regulation.

Notes: Red rectangles represent differentially regulated genes with the fold change indicated at the top edge. Solid arrows show the proposed gene activation cascade based on the transcription factor motifs shared by the genes, the activation levels, and available data from the literature. Green rectangles represent transcription factors whose sites are evolutionarily conserved among three species, with dashed arrows pointing to the associated genes. Pairs of overlapping green rectangles indicate that there were two copies of the identified motif. Dashed rectangles enclose interacting transcription factors. Hypothetical receptor genes are shown in yellow.

Abbreviation: CSEs, chum salmon eggs.

The promoter of the downregulated DUSP1 gene was tightly occupied by CREBs, including CRE-BP1, CRE-BP1:c-Jun, and CREB:ATF unit motifs. HMOX1, FTH1, and SQSTM1 shared the CREB and NF-E2 transcription factors. SQSTM1 showed FOXO1- and NRF2-binding motifs in the promoter but is not included in Table 1 due to its comparatively low fold increase in expression (1.5 in 800 µg/mL). The EGR1 motif was identified in the promoters of the PRDX5 and TXN genes. EGR1 is a well-known target of the estrogen receptor (ESR1);30 thus, we conjectured that ESR1 might mediate CES signaling, with consequent activation of the AML-1a and Elk1 transcription factors.

Discussion

This study represents an initial step toward investigating the beneficial effects of chum salmon egg extract on human dermal fibroblast cell cultures. Our results revealed that treatment with CSE extract enhanced the mRNA expression of type I procollagen (COL1A1 and COL1A2) and led to upregulation of peroxiredoxin system components and other antioxidant genes. Phylogenetic footprinting of the affected antioxidant genes predicted 16 transcription factors, including AML-1a and CREB, to be binding promoter regions of genes induced by CSE supplementation.

A previous study has shown the enhancement of type I collagen in human dermal fibroblasts following supplementation with extracts of beluga sturgeon’s caviar with added CoQ10 and selenium, called LD-1227.15 They reported a 167% increase in collagen type I mRNA with supplementation relative to control. Similarly, our present results showed that CSE supplementation led to COL1A1 increases of 211% with the higher dose and 125% with the lower dose. Although comparison between the previous study and our present study must be made cautiously, we can safely state that our present findings add to the evidence that marine organism-derived extracts can promote antiaging activity, ie, repair of extracellular matrix degeneration from the aging process.

RT2 Profiler PCR Array analysis revealed the strongest upregulation for the PRDX4, PRDX5, and OXR1 genes, with expressions increased by >10-fold with both high and low doses of CSEs. The mechanism of OXR1 activity has not yet been determined, but it plays an important role in protection against oxidative damage.31 Peroxiredoxin family genes along with TXN, TXNRD1, and sulfiredoxin (SRXN1) constitute the peroxiredoxin system, in which peroxiredoxin reduces hydrogen peroxide and TXN acts as an electron donor to peroxiredoxins.32 Most of the genes of the peroxiredoxin system were prominently upregulated by CSE supplementation, and hence we can infer the interplay of the peroxiredoxin system for antioxidant protection. PRDX3 localizes to mitochondria, PRDX4 is found in endoplasmic reticulum, and PRDX5 is mainly present in peroxisomes, mitochondria, and cytosol.33 PRDX4 activity covers a broad spectrum, showing involvement in antioxidant activity in leukemia with the AML-1 and NF-κB genes,34 as well as in controlling neurogenesis in normal cells.35 NF-κB is involved in the oxidative stress response36 and is reportedly specific for the total oxidative stress pathway but not for the CSE-stimulated gene subset. The GPX system is a major pathway for hydrogen peroxide elimination, similar to the peroxiredoxin system and catalase. It is unclear why GPXs did not show prominent fold changes despite prominent upregulation of several genes involved in the GPX system (MGST3, GCLM, and GSTP1). Conceivably, our result might offer insights to dissect the overlapping roles of the GPX and peroxiredoxin systems. Several genes involved in oxidative resistance, such as GPX1, SCARA3, DUSP1, and AOX1, showed reduced expressions with both CSE concentrations and some with a fold change of below −2. However, the number of prominently downregulated genes was 2 with 80 µg/mL and 3 with 800 µg/mL conditions, while the number of prominently upregulated genes was 10 with 80 µg/mL and 14 with 800 µg/mL conditions. With both CSE concentrations, more genes were highly upregulated than were highly downregulated. On the basis of these results, it is reasonable that we infer that CSE supplementation improved the overall antioxidant activity of the cells, with this effect seeming to be dose dependent.

In our dataset, we identified two main kinds of transcription factors: inflammation-response transcription factors (AML-1a, EGR1, and ELK1)37 and DNA damage repair and antioxidant activity transcription factors (CREB, NF-E2, NRF2, c-Myc:Max,38 USF,39 and FOXO1). The involvement of the oncogene AML-1a was surprising. On the other hand, CREB is well known for its role in limiting ROS toxicity in the brain,40,41 as well as its involvement as an effector-like nuclear protein in stress and inflammatory response pathways.28 Together with DUSP1, CREB elicits negative regulation of cellular proliferation under oxidative stress. FOXO1 is a longevity transcription factor42 that promotes repair of DNA oxidative damage, together with the NF-E2 transcription factor43 whose motifs were presently identified in the promoters of the HMOX1, FTH1, and SQSTM1 genes. NRF2, whose motif was found in the SQSTM1 promoter region, is well known for its involvement in oxidative stress responses44 and photoaging resistance.45 EGR1 induces cell apoptosis upon UV irradiation stress,46 and its involvement presupposes an involvement of estrogen receptor (ESR1) in CSE-induced signaling, as shown in Figure 2.

Although it is difficult to predict precisely what triggers the observed beneficial modulations involving numerous genes and transcription factors, we can hypothesize several plausible responsible molecules. Table 3 describes the nourishing qualities of chum salmon egg. One candidate molecule is astaxanthin, which is a precursor of vitamin A17 and an effective antioxidant. Due to its beneficial properties, astaxanthin is already included in some cosmeceutical products, for example, Fujifilm Astalift lineup (http://www.astalift.com.sg). Other candidate active components are yolk-specific proteins, such as phosvitin and lipovitellin. Phosvitin is one of the most phosphorylated proteins in nature and possesses a strong metal-binding ability that makes it useful in antioxidant defense47 and immunoprotection.48 Lipovitellin is classified as a glycolipoprotein and is involved in the storage of nutrients for growth as well as the immune defenses of embryos and larva.49 Moreover, vitellogenin, the precursor of phosvitin and vitellin, is broadly conserved among oviparous animals and is synthesized in the liver and incorporated into oocytes under the control of estrogen.50 Both environmental and injected estrogens influence vitellogenin expression and blood concentration.51,52 Thus, the presence of vitellogenin in CSEs might induce EGR1 upregulation, prompting further potential positive effects on skin rejuvenation53 and skin esthetics. There remains a need for further investigations of estrogen receptors in relation to skin aging.

Table 3.

The composition of chum salmon egg

| Content | Concentration (per 100 g) | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty acids | 14.0 g | Oleic acid (ω9), linoleic acid (ω6), palmitoleic acid (ω7), and DHA and EPA (ω3) |

| Proteins | 31.2 g | Phosvitin, lipovitellin, and lysozyme |

| Vitamin E | 7.2 mg | |

| Vitamin A | 374 µg | |

| Astaxanthin | 0.99 mg |

Abbreviations: DHA, Docosahexaenoic acid; EPS, eicosapentaenoic acid.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our present findings suggested the possibility that CSEs could be effectively used as a source of cosmeceutically active ingredients that exert antiaging and antioxidative effects on the skin. We have also hypothesized the pathway connecting stimulation with CSE extract with the upregulation of several antioxidant genes involving transcription factors, which is characterized by certain beneficial effects to the cell.

Supplementary material

Visualization of the results of promoter analysis of the PRDX4 gene, especially the CREB transcription factor-binding motif.

Notes: The upper left part of the figure shows the orthologous species alignment. The upper right panel shows the Pareto front graph with the CREB motif allocated on the first Pareto front, indicating its strong cross-species conservation and strong matching with a known matrix. The table below lists all candidate motifs with their similarity matching score to the consensus motif and their Pareto front number.

Abbreviation: CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kammeyer A, Luiten RM. Oxidation events and skin aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;21:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velarde MC, Demaria M, Melov S, Campisi J. Pleiotropic age-dependent effects of mitochondrial dysfunction on epidermal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(33):10407–10412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505675112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrakchi S, Maibach HI. Biophysical parameters of skin: map of human face, regional, and age-related differences. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57(1):28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang KA, Yi BR, Choi KC. Molecular mechanisms and in vivo mouse models of skin aging associated with dermal matrix alterations. Lab Anim Res. 2011;27(1):1–8. doi: 10.5625/lar.2011.27.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher GJ, Datta S, Wang Z, et al. c-Jun-dependent inhibition of cutaneous procollagen transcription following ultraviolet irradiation is reversed by all-trans retinoic acid. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(5):663–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI9362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai S, Kitano H. Heterochromatin islands and their dynamic reorganization: a hypothesis for three distinctive features of cellular aging. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33(6):555–570. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quan T, He T, Kang S, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. Solar ultraviolet irradiation reduces collagen in photoaged human skin by blocking transforming growth factor-beta type II receptor/Smad signaling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(3):741–751. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63337-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher GJ, Quan T, Purohit T, et al. Collagen fragmentation promotes oxidative stress and elevates matrix metalloproteinase-1 in fibroblasts in aged human skin. Am J Pathol. 2009;174(1):101–114. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imai S. Is Sirt1 a miracle bullet for longevity? Aging Cell. 2007;6(6):735–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf AM, Nishimaki K, Kamimura N, Ohta S. Real-time monitoring of oxidative stress in live mouse skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(6):1701–1709. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harman D. Free radical theory of aging. Mutat Res. 1992;275(3–6):257–266. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90030-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SK. Marine cosmeceuticals. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:56–67. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu W, Gao J. The use of botanical extracts as topical skin-lightening agents for the improvement of skin pigmentation disorders. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2008;13(1):20–24. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2008.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bledsoe GE, Bledsoe CD, Rasco B. Caviars and fish roe products. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2003;43(3):317–356. doi: 10.1080/10408690390826545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marotta F, Polimeni A, Solimene U, et al. Beneficial modulation from a high-purity caviar-derived homogenate on chronological skin aging. Rejuvenation Res. 2012;15(2):174–177. doi: 10.1089/rej.2011.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee S, Date A, Patravale V, Korting HC, Roeder A, Weindl G. Retinoids in the treatment of skin aging: an overview of clinical efficacy and safety. Clin Interv Aging. 2006;1(4):327–348. doi: 10.2147/ciia.2006.1.4.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamashita E, Arai S, Matsuno T. Metabolism of xanthophylls to vitamin A and new apocarotenoids in liver and skin of black bass, Micropterus salmoides. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;113(3):485–489. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidd P. Astaxanthin, cell membrane nutrient with diverse clinical benefits and anti-aging potential. Altern Med Rev. 2011;16(4):355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lønne GK, Gammelsaeter R, Haglerød C. Composition characterization and clinical efficacy study of a salmon egg extract. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2013;35(5):515–522. doi: 10.1111/ics.12071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polouliakh N, Natsume T, Harada H, Fujibuchi W, Horton P. Comparative genomic analysis of transcription regulation elements involved in human MAP kinase G-protein coupling pathway. J Bioinform Comput Biol. 2006;4(2):469–482. doi: 10.1142/s0219720006001849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suzuki Y, Yamashita R, Nakai K, Sugano S. DBTSS: DataBase of human Transcriptional Start Sites and full-length cDNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):328–331. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polouliakh N, Kitano H, inventor Motif finding program, information processor and motif finding method. 2014/0163894 A1. US. 2014 Edn. G06F 19/18 1-25.

- 23.Wingender E, Dietze P, Karas H, Knüppel R. TRANSFAC: a database on transcription factors and their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(1):238–241. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reguera C, Sánchez MS, Ortiz MC, Sarabia LA. Pareto-optimal front as a tool to study the behaviour of experimental factors in multi-response analytical procedures. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;624(2):210–222. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie X, Lu J, Kulbokas EJ, et al. Systematic discovery of regulatory motifs in human promoters and 3′ UTRs by comparison of several mammals. Nature. 2005;434(7031):338–345. doi: 10.1038/nature03441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsubaki M, Takeda T, Sakamoto K, et al. Bisphosphonates and statins inhibit expression and secretion of MIP-1_ via suppression of Ras/MEK/ERK/AML-1A and Ras/PI3K/Akt/AML-1A pathways. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(1):168–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeda-Sano K, Gotoh M, Morohoshi T, Someya T, Murofushi H, Murakami-Murofushi K. Cyclic phosphatidic acid and lysophosphatidic acid induce hyaluronic acid synthesis via CREB transcription factor regulation in human skin fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841(9):1256–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffrey KL, Camps M, Rommel C, Mackay CR. Targeting dual-specificity phosphatases: manipulating MAP kinase signalling and immune responses. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(5):391–403. doi: 10.1038/nrd2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Funahashi A, Morohashi M, Kitano H, Tanimura N. CellDesigner: a process diagram editor for gene-regulatory and biochemical networks. Biosilico. 2003;1(5):159–162. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim HR, Kim YS, Yoon JA, et al. Egr1 is rapidly and transiently induced by estrogen and bisphenol A via activation of nuclear estrogen receptor-dependent ERK1/2 pathway in the uterus. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;50:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volkert MR, Elliott NA, Housman DE. Functional genomics reveals a family of eukaryotic oxidation protection genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(26):14530–14535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260495897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu J, Holmgren A. The thioredoxin antioxidant system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;66:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhee SG, Woo HA, Kil IS, Bae SH. Peroxiredoxin functions as a peroxidase and a regulator and sensor of local peroxides. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4403–4410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.283432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Emmanuel N, Kamboj G, et al. PRDX4, a member of the peroxiredoxin family, is fused to AML1 (RUNX1) in an acute myeloid leukemia patient with a t(X;21)(p22;q22) Genes Chromosom Cancer. 2004;40(4):365–370. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan Y, Wladyka C, Fujii J, Sockanathan S. Prdx4 is a compartment-specific H2O2 sensor that regulates neurogenesis by controlling surface expression of GDE2. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayem AA, Choi HY, Kim JH, Cho SG. Role of oxidative stress in stem, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Cancers (Basel) 2010;2(2):859–884. doi: 10.3390/cancers2020859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavalcanti FN, Lucas TF, Lazari MF, Porto CS. Estrogen receptor ESR1 mediates activation of ERK1/2, CREB, and ELK1 in the corpus of the epididymis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2015;54(3):339–349. doi: 10.1530/JME-15-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nichols AF, Itoh T, Zolezzi F, Hutsell S, Linn S. Basal transcriptional regulation of human damage-specific DNA-binding protein genes DDB1 and DDB2 by Sp1, E2F, N-myc and NF1 elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(2):562–569. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baron Y, Corre S, Mouchet N, Vaulont S, Prince S, Galibert MD. USF-1 is critical for maintaining genome integrity in response to UV-induced DNA photolesions. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(1):e1002470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee B, Cao R, Choi YS, et al. The CREB/CRE transcriptional pathway: protection against oxidative stress-mediated neuronal cell death. J Neurochem. 2009;108(5):1251–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Jope RS. Oxidative stress differentially modulates phosphorylation of ERK, p38 and CREB induced by NGF or EGF in PC12 cells. Neurobiol Aging. 1999;20(3):271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Wang WJ, Cao H, et al. Genetic association of FOXO1A and FOXO3A with longevity trait in Han Chinese populations. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(24):4897–4904. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timme-Laragy AR, Karchner SI, Franks DG, et al. Nrf2b, novel zebrafish paralog of oxidant-responsive transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(7):4609–4627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gruber F, Ornelas CM, Karner S, et al. Nrf2 deficiency causes lipid oxidation, inflammation and matrix-protease expression in DHA supplemented and UVA irradiated skin fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;(88Pt B):439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tian FF, Zhang FF, Lai XD, et al. Nrf2-mediated protection against UVA radiation in human skin keratinocytes. Biosci Trends. 2011;5(1):23–29. doi: 10.5582/bst.2011.v5.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arora S, Wang Y, Jia Z, et al. Egr1 regulates the coordinated expression of numerous EGF receptor target genes as identified by ChIP-on-chip. Genome Biol. 2008;9(11):R166. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-11-r166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee SK, Han JH, Decker EA. Antioxidant activity of phosvitin in phosphatidylcholine liposomes and meat model systems. J Food Sci. 2002;67(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang S, Wang Y, Ma J, Ding Y, Zhang S. Phosvitin plays a critical role in the immunity of zebrafish embryos via acting as a pattern recognition receptor and an antimicrobial effector. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(25):22653–22664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Zhang S. Lipovitellin is a non-self recognition receptor with opsonic activity. Mar Biotechnol. 2011;13:441–450. doi: 10.1007/s10126-010-9315-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bergink EW, Wallace RA, Van De Berg JA, Bos ES, Gruber M, Ab G. Estrogen-induced synthesis of yolk proteins in roosters. Am Zool. 1974;14:1177–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Idler DR, Campbell CM. Gonadotropin stimulation of estrogen and yolk precursor synthesis in juvenile rainbow trout. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 1980;41:384–391. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(80)90083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tada N, Nakao A, Hoshi H, Saka M, Kamata Y. Vitellogenin, a biomarker for environmental estrogenic pollution, of Reeves’ pond turtles: analysis of similarity for its amino acid sequence and cognate mRNA expression after exposure to estrogen. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70:227–234. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cortés-Gallegos V, Villanueva GL, Sojo-Aranda I, Santa Cruz FJ. Inverted skin changes induced by estrogen and estrogen/glucocorticoid on aging dermis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1996;10:125–128. doi: 10.3109/09513599609097902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Visualization of the results of promoter analysis of the PRDX4 gene, especially the CREB transcription factor-binding motif.

Notes: The upper left part of the figure shows the orthologous species alignment. The upper right panel shows the Pareto front graph with the CREB motif allocated on the first Pareto front, indicating its strong cross-species conservation and strong matching with a known matrix. The table below lists all candidate motifs with their similarity matching score to the consensus motif and their Pareto front number.

Abbreviation: CREB, cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein.