Abstract

Background:

CrossFit is a conditioning and training program that has been gaining recognition and interest among the physically active population. Approximately 440 certified and registered CrossFit fitness centers and gyms exist in Brazil, with approximately 40,000 athletes. To date, there have been no epidemiological studies about the CrossFit athlete in Brazil.

Purpose:

To evaluate the profile, sports history, training routine, and presence of injuries among athletes of CrossFit.

Study Design:

Descriptive epidemiological study.

Methods:

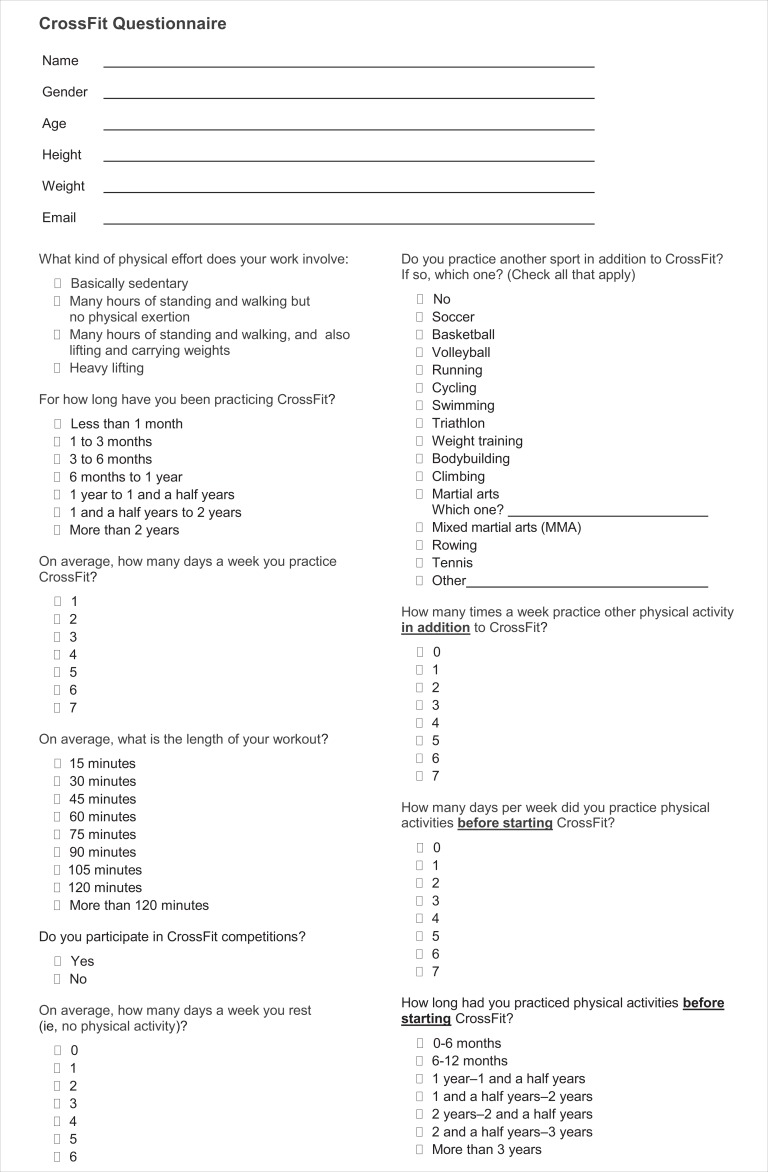

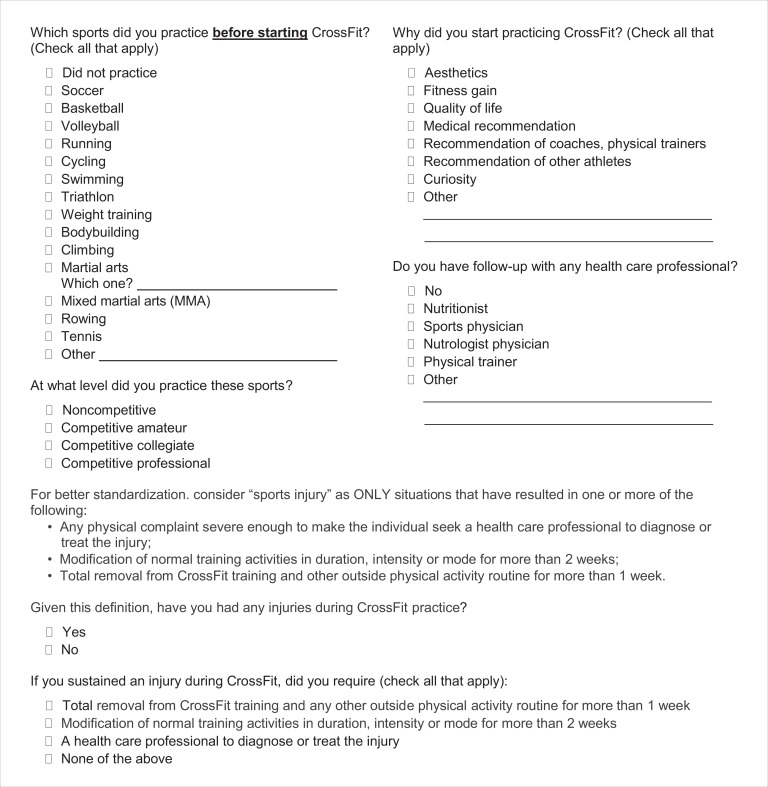

This cross-sectional study was based on a questionnaire administered to CrossFit athletes from various specialized fitness centers in Brazil. Data were collected from May 2015 to July 2015 through an electronic questionnaire that included demographic data, level of sedentary lifestyle at work, sports training history prior to starting CrossFit, current sports activities, professional monitoring, and whether the participants experienced any injuries while practicing CrossFit.

Results:

A total of 622 questionnaires were received, including 566 (243 women [42.9%] and 323 men [57.1%]) that were completely filled out and met the inclusion criteria and 9% that were incompletely filled out. Overall, 176 individuals (31.0%) mentioned having experienced some type of injury while practicing CrossFit. We found no significant difference in injury incidence rates regarding demographic data. There was no significant difference regarding previous sports activities because individuals who did not practice prior physical activity showed very similar injury rates to those who practiced at any level.

Conclusion:

CrossFit injury rates are comparable to those of other recreational or competitive sports, and the injuries show a profile similar to weight lifting, power lifting, weight training, Olympic gymnastics, and running, which have an injury incidence rate nearly half that of soccer.

Keywords: CrossFit, competitive exercise, weight lifting, fitness, cross-sectional study

CrossFit is a conditioning and training program that has been gaining recognition and interest among the physically active population. This program was initially developed for military training and gradually spread among the civilian population. It is based on a set of complex exercises and includes running, weightlifting, Olympic gymnastics, and ballistic movements.4 The exercises are usually combined with high-intensity workout routines and are performed quickly, repetitively, and with limited or no recovery time between sets. Impressive physical conditioning gains have been reported. Approximately 440 certified and registered CrossFit fitness centers and gyms exist in Brazil, totaling approximately 40,000 athletes.

Recent studies show that practicing CrossFit improves metabolic capacity and physical conditioning when assessing the maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) and body composition of athletes with different levels of physical fitness.17 Another study, conducted by the United States Army, noted that including CrossFit in the training routine of soldiers significantly improved their physical conditioning.14 However, a different study showed no difference in the incidence of injuries and wounds in battle and missions.6 There is much concern regarding the high musculoskeletal injury rates; however, these data are controversial in the literature because only 2 studies on the subject using a civilian population have been published: 1 reporting a 19.4% incidence19 and another reporting a 73.5% incidence of injuries.7

The primary objective of this pioneering study in Brazil is to examine the profile of athletes or regular members of CrossFit fitness centers and gyms in Brazil and their history of sports activities, training routine, and habits and the incidence of injuries during this practice. Furthermore, the secondary objective of the study is to identify patterns of association between the training characteristics, routine, and incidence of injuries. The identification of risk factors enables the design of effective strategies to reduce injury rates.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was based on a questionnaire administered to CrossFit athletes from 250 specialized fitness centers in Brazil that were certified and registered in the CrossFit database. Data were collected from May 2015 to July 2015 through an electronic questionnaire created and hosted using an online questionnaire and survey software (SurveyMonkey; www.surveymonkey.com). This study was submitted and approved by the ethics committee of Santa Casa de São Paulo.

This questionnaire included demographic data, such as age, sex, level of sedentary lifestyle at work, sports training history prior to starting CrossFit, current training routine, concurrent practice of other sports activities, professional monitoring, and whether the participants experienced some type of injury while practicing CrossFit (Appendix).

We considered an injury, as defined in a prior study,19 as any new musculoskeletal pain, feeling, or traumatic event that results from a CrossFit workout and leads to 1 or more of the following options: total removal from CrossFit training and other outside routine physical activities for more than 1 week; modification of normal training activities in duration, intensity, or mode for more than 2 weeks; or any physical complaint severe enough to make the individual seek a health care professional to diagnose or treat the injury.

This research study was emailed to owners, managers, and specialized instructors of CrossFit fitness centers and gyms so that they would forward the digital link to their members and clients. Instructors and owners were encouraged to forward the questionnaire to other gyms and fitness centers. A total of 54 centers answered the questionnaire.

The inclusion criterion consisted of athletes of this sport training in specialized and certified fitness centers and gyms who completely filled out the study questionnaire. The exclusion criteria consisted of individuals training in noncertified fitness centers or on their own, incomplete questionnaires, and individuals who did not agree to sign the informed consent form.

Sample Calculation

The sample size needed to assess the injury prevalence rates among the population of CrossFit athletes was calculated. The sample size required to perform the study was 591 people, considering approximately 40,000 athletes of CrossFit and assuming a conservative sample needed to assess the injury prevalence rates, that is, 50% injury, with a 95% CI and 4% accuracy of injury prevalence rates.

Statistical Analysis

The injury prevalence rates were reported based on personal, sports practice, and behavioral characteristics. The quantitative variables are described using summary measures (mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum),8 and the qualitative characteristics are described using the absolute, relative, and verified frequencies.8

Bivariate logistic regressions9 were performed for each characteristic of interest to assess the effect on the injury prevalence rates and to estimate the odd ratios (ORs) with the respective 95% CIs, which represented the effect size. Subsequently, multiple logistic regression models9 were estimated to explain the injury prevalence rates by selecting the variables that showed significance levels lower than 0.20 (P < .20) in the bivariate tests in addition to variables with clinical plausibility for injury occurrence. The tests were performed at a 5% significance level.

Results

A total of 622 questionnaires were received, including 566 (243 women [42.9%] and 323 men [57.1%]) that were completely filled out and met the inclusion criteria and 9% that were incompletely filled out. The mean age of athletes was 31.4 years and ranged from 13 to 58 years; most athletes were in the 18- to 39-year-old age group (87.9%). We identified 9 individuals younger than 18 years of age (including one 13-year-old, four 15-year-olds, two 16-year-olds, and two 17-year-olds). The mean height was 1.71 m, the mean weight was 74.2 kg, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.1 kg/m2. Most (58.0%) athletes reported that their work was basically sedentary, characterized by long hours sitting down and short periods of time walking without physical exertion (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data and Profile (N = 566 participants)

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 243 (42.9) |

| Male | 323 (57.1) |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| <18 y | 9 (1.6) |

| 18-29 y | 230 (40.6) |

| 30-39 y | 268 (47.3) |

| 40-49 y | 48 (8.5) |

| ≥50 y | 11 (1.9) |

| Mean ± SD | 31.3 ± 7 |

| Median (range) | 31 (13-58) |

| Type of physical exertion at workplace, n (%) | |

| Sedentary | 328 (58) |

| Standing and walking, without physical exertion | 109 (19.3) |

| Standing and walking, lifting and loading weights | 125 (22.1) |

| Heavy lifting | 4 (0.7) |

| Height, cm | |

| Mean ± SD | 171.5 ± 9.1 |

| Median (range) | 171 (146-197) |

| Weight, kg | |

| Mean ± SD | 74.2 ± 15.4 |

| Median (range) | 74 (46-165) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |

| Mean ± SD | 25.1 ± 3.8 |

| Median (range) | 24.6 (17.2-63.7) |

Regarding prior practice of sports activities, 35 individuals (6.2%) reported no physical activity before starting CrossFit, 144 (27.1%) reported activity 1 to 2 times per week, 194 (34.2%) reported activity 3 to 4 times per week, and 193 (36.3%) reported practicing physical activities more than 4 times per week. Among those who practiced physical activity, most (356, 67.0%) reported performing physical activities for more than 3 years. Several individuals (254, 44.87%) reported practicing more than 1 sports activity. The main sports activity reported was weight training (383 athletes, 72.1%), followed by running (196 athletes, 36.9%), soccer (102 athletes, 19.2%), and martial arts (97 athletes, 18.3%). When asked about the level of practice of these sports activities, 68.4% of athletes reported that they practiced sports activities at a noncompetitive level, 23.9% practiced at a competitive amateur level, and only 7.7% participated in collegiate or professional competitions (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sports Training History Prior to Practicing CrossFita

| Any sports participation before starting CrossFit? | |

| No | 35 (6.2) |

| Yes | 531 (93.8) |

| Practice frequencyb | |

| 1-2 times/wk | 144 (27.1) |

| 3-4 times/wk | 194 (36.5) |

| >4 times/wk | 193 (36.3) |

| Practice timeb | |

| <1 y | 78 (14.7) |

| 1-3 y | 97 (18.3) |

| >3 y | 356 (67) |

| Type of sport practicedb | |

| Soccer | 102 (19.2) |

| Basketball | 21 (4) |

| Volleyball | 22 (4.1) |

| Running | 196 (36.9) |

| Cycling | 73 (13.7) |

| Swimming | 80 (15.1) |

| Weight training | 383 (72.1) |

| Bodybuilding | 4 (0.8) |

| Climbing | 13 (2.4) |

| Martial arts | 92 (18.3) |

| Mixed martial arts (MMA) | 12 (2.3) |

| Rowing | 3 (0.6) |

| Tennis | 22 (4.1) |

| Other | 96 (18.1) |

| Level of sport practicedb | |

| Noncompetitive | 363 (68.4) |

| Competitive, amateur | 127 (23.9) |

| Competitive, collegiate | 19 (3.6) |

| Competitive, professional | 22 (4.1) |

aData are reported as n (%).

bOnly applicable to those who previously practiced sports.

When questioned about all possible motivations to start practicing CrossFit, 410 respondents (72.4%) answered that they started this activity to improve physical conditioning, 327 (57.8%) reported seeking a better quality of life, 233 (41.2%) reported curiosity, and 196 (34.6%) reported esthetic gains.

Regarding their current physical activity, 179 athletes (31.6%) reported practicing CrossFit for less than 6 months, 164 (29.0%) reported practicing CrossFit from 6 months to 1 year, and 233 (39.4%) reported practicing CrossFit for more than 1 year. No participant reported practicing CrossFit only 1 time per week, 30 (5.3%) reported practicing 2 times per week, 294 (51.9%) reported practicing from 3 to 4 times per week, and 242 individuals (42.8%) reported practicing more than 4 times per week. Approximately one-third of respondents (185, 32.7%) reported participating in CrossFit competitions.

A total of 328 respondents (58%) reported performing other physical activities in addition to CrossFit. Among these respondents, 72.6% (238 respondents) practiced these other activities 1 to 2 times per week. The majority of respondents (404, 71.4%) reported that they rested 1 to 2 times a week, in which they did not practice any other sport. When asked about which other sport they practiced, 156 individuals (47.6%) reported running, 73 (22.3%) reported various other activities (the most cited activities included surfing, yoga, and Pilates), 58 (17.7%) reported weight training, and 51 (15.5%) reported cycling.

When asked about monitoring performed by a health care professional, 319 individuals (56.4%) reported having professional monitoring and 247 (43.6%) reported having no monitoring whatsoever. The vast majority of participants who gave a positive response regularly attended appointments with a nutritionist (254 respondents, 79.6%).

Injuries

Overall, 176 individuals (31.0%) mentioned having experienced some type of injury while practicing CrossFit. Among these, 74 (42.0%) reported seeking a health care professional to diagnose or treat the injury; 59 (33.5%) reported having to modify their normal training in length, intensity, or any other characteristic for more than 2 weeks, although without requiring any specialized treatment; and 42 (24.0%) reported having to completely refrain from practicing CrossFit or any other physical activity for more than 1 week, also without any specific treatment.

We found no significant difference in injury incidence rates regarding sex or age group. In addition, no significant difference regarding the anthropometric data, including weight, height, and BMI, was observed. There was no significant difference regarding previous sports activities because individuals who practiced no prior physical activity or practiced at various levels showed very similar injury rates.

No significant difference in injury rates was found with respect to the length of training sessions, weekly training frequency, concurrent practice of other physical activities, and resting frequency (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Injury Rate Analysis

| Sustained an Injury While Practicing CrossFit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No | Yes | Total Responses | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Sex, n (%) | .105 | ||||

| Female | 176 (72.4) | 67 (27.6) | 243 | 1 | |

| Male | 214 (66) | 109 (34) | 323 | 1.35 (0.939-1.942) | |

| Age, y | .361 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 31.1 (7.3) | 31.7 (6.3) | 31.3 (7) | 1.012 (0.987-1.037) | |

| Median (range) | 31 (13-56) | 31 (19-58) | 31 (13-58) | ||

| Height, cm | .287 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 171.2 (9.2) | 172.1 (8.9) | 171.5 (9.1) | 1.011 (0.991-1.031) | |

| Median (range) | 171 (146-193) | 172 (150-197) | 171 (146-197) | ||

| Weight, kg | .212 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 73.7 (14.9) | 75.4 (16.4) | 74.2 (15.4) | 1.007 (1.996-1.019) | |

| Median (range) | 73 (47-163) | 74 (46-165) | 74 (46-165) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | .355 | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 25 (3.7) | 25.3 (3.9) | 25.1 (3.8) | 1.022 (1.976-1.069) | |

| Median (range) | 24.6 (17.6-63.7) | 24.6 (17.2-53.3) | 24.6 (17.2-63.7) | ||

| CrossFit frequency, n (%) | .581 | ||||

| <3 times/wk | 22 (73.3) | 8 (26.7) | 30 | 1 | |

| ≥3 times/wk | 368 (68.5) | 168 (31.5) | 536 | 1.263 (0.551-2.895) | |

| Length of training sessions, n (%) | .126 | ||||

| <1 h | 23 (82.1) | 5 (17.9) | 28 | 1 | |

| ≥1 h | 367 (68.1) | 171 (31.9) | 538 | 2.156 (0.806-5.767) | |

| CrossFit competitions, n (%) | .006a | ||||

| No | 277 (72.5) | 105 (27.5) | 382 | 1 | |

| Yes | 113 (61.1) | 72 (38.9) | 185 | 1.681 (1.16-2.436) | |

| Rest frequency, n (%) | .809 | ||||

| <3 times/wk | 288 (69.1) | 129 (30.9) | 417 | 1 | |

| ≥3 times/wk | 102 (68) | 47 (32) | 149 | 1.051 (0.704-1.569) | |

| Practice another sport, n (%) | .673 | ||||

| No | 166 (69.7) | 72 (30.3) | 238 | 1 | |

| Yes | 224 (68.1) | 104 (31.9) | 328 | 1.081 (0.753-1.55) | |

| Frequency of other sports, n (%) | .637 | ||||

| <3 times/wk | 330 (39.2) | 146 (30.8) | 476 | 1 | |

| ≥3 times/wk | 60 (66.7) | 30 (33.3) | 90 | 1.122 (0.695-1.813) | |

| Sports participation before CrossFit, n (%) | .978 | ||||

| No | 24 (68.6) | 11 (31.4) | 35 | 1 | |

| Yes | 366 (68.8) | 165 (31.2) | 531 | 0.99 (0.474-2.068) | |

| Level of sport practiced, n (%) | .837 | ||||

| Noncompetitive | 271 (68.1) | 127 (31.9) | 398 | 1 | |

| Competitive, amateur | 89 (69.5) | 38 (30.5) | 127 | 0.935 (0.607-1.439) | |

| Competitive, collegiate | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | 19 | 0.985 (0.366-2.651) | |

| Competitive, professional | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | 22 | 0.628 (0.227-1.739) | |

| Monitored by a health care professional to improve performance, n (%) | .086 | ||||

| No | 180 (72.6) | 67 (27.4) | 247 | 1 | |

| Yes | 210 (65.8) | 109 (34.2) | 319 | 1.374 (0.956-1.974) | |

| Practice time, n (%) | .004a | ||||

| >6 mo | 138 (77.1) | 41 (22.9) | 179 | 1 | |

| <6 mo | 252 (64.9) | 135 (35.1) | 387 | 1.816 (1.21-2.727) | |

aWhen analyzed alone, participation in competitions and length of CrossFit practice significantly increased injury frequency rates (P < .05).

We also separated participants according to length of practice, and those who practiced CrossFit for more than 6 months (35.1%) showed significantly (P = .004) higher injury rates than those who practiced for less than 6 months (22.9%). We observed a 44.9% injury incidence rate among athletes with more than 2 years of practice. Participation in CrossFit competitions is also an injury risk factor, but not when it is analyzed separately, as people who compete tend to have practiced CrossFit for more time (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Isolated Injury Risk Factors

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 1.31 (0.904-1.899) | .154 |

| Age | 1.009 (0.983-1.035) | .505 |

| Length of training sessions ≥1 h | 2.216 (0.819-5.992) | .117 |

| Participation in CrossFit competitions | 1.02 (0.705-1.475) | .917 |

| Professional monitoring | 1.306 (0.901-1.892) | .159 |

| CrossFit practice time >6 moa | 1.697 (1.12-2.572) | .013 |

aOnly length of practicing CrossFit significantly affected injury frequency rates, and individuals who have practiced the sport for more than 6 months are 70% more likely to have suffered an injury, regardless of the other characteristics assessed. P value in boldface indicates statistical significance.

Table 4 shows that only the length of practicing CrossFit significantly affects injury frequency rates and that individuals who have practiced the sport for more than 6 months are 70% more likely to have suffered an injury, regardless of the other characteristics assessed.

Discussion

CrossFit is defined as “functional, constantly varied, and high-intensity training,” and no aspect is more important than the capacity to quickly move heavy loads over long distances.4 The CrossFit workout routine consists of a combination of multiple synchronic exercises, including Olympic gymnastics, weight lifting (Olympic and standard), short-distance running, jumps, and exercises performed using the participant’s own bodyweight (push-ups and chin-ups). These movements are often performed at high intensity with little or no rest between sets. Thus, studies have predicted high injury rates among CrossFit athletes, given the highly complex, high-intensity, repetitive movements.1

In the present study, we observed an overall injury incidence of approximately 31% in CrossFit participants. Similar injury rates have been reported2,5,10,15 when comparing CrossFit to other physical activities with similar movements, including weight lifting, power lifting, and Olympic gymnastics. We also found injury rates similar to those of CrossFit when comparing CrossFit to other activities related to physical conditioning and fitness,16 including weight training, running (short, middle, and long distance),12 and triathlon.11

When comparing CrossFit to the most popular physical activity in our country, soccer, we observed much higher injury rates in soccer (from 57% to 61.8%, almost twice the incidence of CrossFit injuries); however, the 2 referenced studies only analyzed 1 training season in both amateur and professional athletes.13,18

The practice of CrossFit by individuals younger than 18 years may present a greater risk for injuries, although a recent study showed that this training routine is feasible and safe and effectively improves physical conditioning and health in children.3

The need to perform sports movements and gestures correctly, thus minimizing the possibility of injuries, must be emphasized because this is a complex workout routine that is performed while the participant experiences muscle fatigue. Another key issue is the presence of an instructor because the lack thereof is associated with a greater incidence of injuries.19

The present study has limitations because the questionnaire was distributed electronically, with the aim of reaching a larger audience, which may generate a selection bias because people who have experienced some type of injury may feel more inclined to answer the questionnaire. Furthermore, we were dependent on the athlete for injury interpretation. Delayed muscle pain may be misinterpreted as injury, and such pain is extremely common in high-intensity activities.

In general, CrossFit athletes are usually young individuals with prior sports experience, and most are physically active. They find themselves drawn to this dynamic training routine to improve their physical conditioning and, as many reported, because they find conventional training methods, including weight training and other fitness center activities, monotonous.

To our knowledge, this report is the first Brazilian study and the largest sample worldwide to examine this new training method. Further studies are required to expand the knowledge of injuries associated with CrossFit and their prevention. Future studies will provide more detail on the injuries sustained by examining the injury location, number of injuries, required treatment, and movements and exercises that caused them. These reports will use the database created for this study.

Conclusion

CrossFit is a training method that is becoming increasingly popular in both competitive and noncompetitive forms and is focused on physical conditioning. With a gradual increase in the number of athletes, the absolute number of injuries will consequently increase. Orthopedists and sports physicians should be familiar with this new type of exercise so that they can properly counsel and treat their patients.

CrossFit injury rates are comparable to those of other recreational or competitive sports, and the injuries show a profile similar to weight lifting, power lifting, weight training, Olympic gymnastics, and running, which have an injury incidence rate nearly half of that of soccer.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mr Joel Fridman, whose valuable help was instrumental to this research. They also have to mention the important contribution of all gym owners and trainers that made forwarding this questionnaire possible. Last but not least, the authors would like to thank all the athletes who gave their valuable time to answer the questions, allowing the authors to gather the information needed for this work.

Appendix

CrossFit Questionnaire

Footnotes

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this contribution.

References

- 1. Bergeron MF, Nindl BC, Deuster PA, et al. Consortium for Health and Military Performance and American College of Sports Medicine consensus paper on extreme conditioning programs in military personnel. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2011;10:383–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calhoon G, Fry AC. Injury rates and profiles of elite competitive weightlifters. J Athl Train. 1999;34:232–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eather N, Morgan PJ, Lubans DR. Improving health-related fitness in adolescents: the CrossFit Teens™ randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci. 2016;34:209–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glassman G. Understanding CrossFit. Crossfit J. 2007;56:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goertzen M, Schöppe K, Lange G, Schulitz KP. Injuries and damage caused by excess stress in body building and power lifting [in German]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1989;3:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grier T, Canham-Chervak M, McNulty V, Jones BH. Extreme conditioning programs and injury risk in a US Army Brigade Combat Team. US Army Med Dep J. 2013;10-12:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hak PT, Hodzovic E, Hickey B. The nature and prevalence of injury during CrossFit training [published online November 22, 2013]. J Strength Cond Res. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed New York, NY: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kirkwood BR, Sterne JAC. Essential Medical Statistics. 2nd ed Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Science; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kolt GS, Kirkby RJ. Epidemiology of injury in elite and subelite female gymnasts: a comparison of retrospective and prospective findings. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33:312–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Korkia PK, Tunstall-Pedoe DS, Maffulli N. An epidemiological investigation of training and injury patterns in British triathletes. Br J Sports Med. 1994;28:191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lysholm J, Wiklander J. Injuries in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:168–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nilstad A, Andersen TE, Bahr R, Holme I, Steffen K. Risk factors for lower extremity injuries in elite female soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:940–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paine J, Uptgraft J, Wylie R. CrossFit study, May 2010. http://cgsc.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p124201coll2/id/580. Accessed March 11, 2015.

- 15. Raske A, Norlin R. Injury incidence and prevalence among elite weight and power lifters. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Requa RK, DeAvilla LN, Garrick JG. Injuries in recreational adult fitness activities. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith MM, Sommer AJ, Starkoff BE, Devor ST. Crossfit-based high-intensity power training improves maximal aerobic fitness and body composition. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27:3159–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sousa P, Rebelo A, Brito J. Injuries in amateur soccer players on artificial turf: a one-season prospective study. Phys Ther Sport. 2013;14:146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weisenthal BM, Beck CA, Maloney MD, DeHaven KE, Giordano BD. Injury rate and patterns among CrossFit athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(4):23259 67114531177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]