Abstract

Aegilops variabilis (UUSvSv), an important sources for wheat improvement, originated from chromosome doubling of a natural hybrid between Ae. umbellulata (UU) with Ae. longissima (SlSl). The Ae. variabilis karyotype was poorly characterized by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). The FISH probe combination of pSc119.2, pTa71 and pTa-713 identified each of the 14 pairs of Ae. variabilis chromosomes. Our FISH ideogram was further used to detect an Ae. variabilis chromosome carrying stripe rust resistance in the background of wheat lines developed from crosses of the stripe rust susceptible bread wheat cultivar Yiyuan 2 with a resistant Ae. variabilis accession. Among the 15 resistant BC1F7 lines, three were 2Sv + 4Sv addition lines (2n = 46) and 12 were 2Sv(2B) or 2Sv(2D) substitution lines that were confirmed with SSR markers. SSR marker gwm148 can be used to trace 2Sv in common wheat background. Chromosome 2Sv probably carries gametocidal(Gc) gene(s) since cytological instability and chromosome structural variations, including non-homologous translocations, were observed in some lines with this chromosome. Due to the effects of photoperiod genes, substitution lines 2Sv(2D) and 2Sv(2B) exhibited late heading with 2Sv(2D) lines being later than 2Sv(2B) lines. 2Sv(2D) substitution lines were also taller and exhibited higher spikelet numbers and longer spikes.

Keywords: additional line, Aegilops variabilis, FISH, Puccinia striiformis, substitution line, translocation line

Introduction

Triticeae within the Pooideae subfamily of grasses is a large tribe that contains over 500 species and about 30 genera depending on the opinions of taxonomists (Wang and Lu 2014, Yen et al. 2005, Yen and Yang 2009). These species provide a vast gene pool for the genetic improvement of common wheat (Triticum aestivum, 2n = 6× = 42, AABBDD genome). The Aegilops genus consists of 10 diploid, 10 tetraploid, and 2 hexaploid species (van Slageren 1994). The genus is closely related to Triticum and played an important role in the evolution of common wheat. The ancestor of the D-genome of wheat is Ae. tauschii (Kihara 1944, McFadden and Sears 1944), whereas the B-genome is thought to be a differentiated S-genome from Ae. speltoides or a closely related species (Kilian et al. 2007, Petersen et al. 2006). In addition to Ae. speltoides the S-genome is also shared by the diploid species Ae. longissima (Sl), Ae. sharonensis (Ssh), Ae. searsii (Ss), and Ae. bicornis (Sb) in the Sitopsis section of genus Aegilops (van Slageren 1994).

Ae. variabilis Eig [syn. Ae. peregrina (Hack.) Maire and Weiller; 2n = 4× = 28, SvSvUU] was derived from hybridization of the diploid species Ae. umbellulata (UU) and Ae. longissima (SlSl) (Kihara 1954, Yu and Jahier 1992). Ae. variabilis is a test genotype widely used in detection of homeologous chromosome pairing genes (Sears 1976). Ae. variabilis also contains desirable traits for common wheat improvement, such as high concentrations of iron and zinc in the grain (Neelam et al. 2011), resistance to Meloidogyne naasi (root knot nematode) and Heterodera avenae (cereal cyst nematode) (Barloy et al. 2007, Yu et al. 1990, 1992), powdery mildew (Spetsov et al. 1997), leaf rust (Marais et al. 2008), stripe rust (Liu et al. 2011), spot blotch, and Karnal bunt (Mujeeb-Kazi et al. 2007).

Wheat stripe rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst) is one of the most serious wheat diseases worldwide (Chen 2005). In China, the disease is more prevalent in southwest and northwest regions due to favorable climatic conditions (Wan et al. 2007). Following the emergence of Pst races CYR32 detected in 1994 and CYR33 detected in 1997 most wheat cultivars in southwest China became susceptible, except those with resistance gene(s) Yr24/Yr26 (Chen et al. 2009, Liu et al. 2013, Wan et al. 2004). Yr24/Yr26 was the most frequently used resistance source in wheat breeding lines and currently grown cultivars in the region; but a new Pst race (or races) known as v26 (also called CH42) was first reported in Sichuan province in 2008–2009 (Liu et al. 2010). During 2014 and 2015, most of the commercial wheat cultivars in Sichuan province were susceptible and epidemics of v26 led to significant yield losses. Therefore, it is urgent to identify effective stripe rust resistance genes for deployment in new cultivars to prevent future stripe rust epidemics.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is widely used in identification of alien chromosomes in wheat. Although Ae. variabilis was cytologically characterized using FISH markers (Badaeva et al. 2004); however, some Ae. variabilis chromosomes could not be identified. The objective of this study was to identify fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) patterns of Ae. variabilis chromosomes using different repetitive sequences, with the aim of identifying each of the 14 pairs of chromosomes. The resulting FISH patterns were further used to detect the Ae. variabilis chromosome carrying stripe rust resistance in wheat BC1F7 lines that were derived from a cross of Ae. variabilis with susceptible bread wheat cultivar Yiyuan 2 and backcross to Yiyuan 2.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

The plant genotypes used in this study included Ae. variabilis AS116 (2n = 4× = 28, SvSvUU), common wheat line Yiyuan 2 (2n = 6× = 42, AABBDD), and 26 homozygous BC1F7 derivatives with the cytoplasm of Ae. variabilis were generated by selection for fertility, stripe rust resistance and desirable agronomic traits. Chinese Spring (CS) nullisomic-tetrasomic (NT) lines for homoeologous group 2 were used for molecular marker location. Stripe rust susceptible wheat line SY95-71 was used as a disease spreader.

Evaluation of agronomic traits

All lines were planted at Wenjiang Experimental Station, Sichuan Agricultural University. In the 2013–2014 cropping season, 20 plants of each BC1F7 selection and parental lines were space-planted in 2.0 m rows, with 30 cm between rows. This experiment consisted of three replicates. In the 2014–2015 season, each line was grown in a five-row plot with 20 plants per row. The highly susceptible spreader line SY95-71 was planted on both sides of each experimental row.

All materials were inoculated with mixed urediniospores of races CYR32, CYR33, Gui22-9, Gui22-14, Su11-4, and Su11-5 in 2014 and CYR32, CYR33, Gui22-9, Gui22-14, Gui22-8, Su11-4, and Su11-5 in 2015, provided by the Research Institute of Plant Protection, Gansu Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Infection types on individual plants after heading were recorded three times at 10-day intervals on a 0–9 scale (McNeal et al. 1971) when the spreader line SY95-71 was fully infected.

Heading time was recorded in both years when approximately one-half of the spikes in each line had emerged. Waxiness, a morphological marker associated with variation in homoeologous group 2 chromosomes, was also recorded at anthesis in 2015. Other agronomic traits (plant height, tiller number per plant, spike length and spikelet number) were evaluated at maturity from 10 randomly selected plants from each plot. The three tallest tillers of the selected plant were measured for plant height, spike length and spikelet number. Plant height was calculated as the average height from the soil surface to the tip of the spike (awns excluded). The average value for each trait was then calculated.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Root tips excised from germinating seeds were treated for 2 hours with nitrous oxide and then placed in 70% ethanol (Kato 1999). Root tips were treated with cellulase and pectinase and the suspension was dropped onto slides (Komuro et al. 2013). The slides were prepared for FISH as previously described by Hao et al. (2011, 2013). Before chromosomal observations, DAPI was applied to the slides. After capturing images coverslips were removed, the slides were washed gently with 70% ethanol, then submerged in boiling 2× SSC buffer (100°C) for 5 min to remove probes, washed with distilled water, briefly rinsed with 70% ethanol, and air dried for the next FISH (Komuro et al. 2013). Probes pSc119.2, pAs1, pTa-535, pTa71 (Tang et al. 2014), (GAA)5 (Cuadrado et al. 2008, Dennis et al. 1980), and pTa-713 (FAM or TAM 5′ AGACGAGCACGTGACACCATTCCCACCCTGTCTTAGCGTAACGCGAGTCG 3′) designed according to Komuro et al. (2013) were used. All the probes are oligonucleotides and were synthesized by TSINGKE (Chengdu, China).

SSR analysis

To identify substituted chromosomes, 62 wheat microsatellite (SSR) markers on 2B and 2D were used based on genetic-physical maps of Sourdille et al. (2004) and GrainGenes website (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG3/maps). Genomic DNA from plant materials were extracted from young leaves using a plant genomic DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech (Beijing) Co. Ltd). PCR amplifications were performed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Singapore) with the following conditions: 95°C for 4 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 10 min. Amplification products were separated on 3% agarose gels in TAE buffer and visualized under UV light with ethidium bromide.

Results

Identification of parent chromosomes by FISH

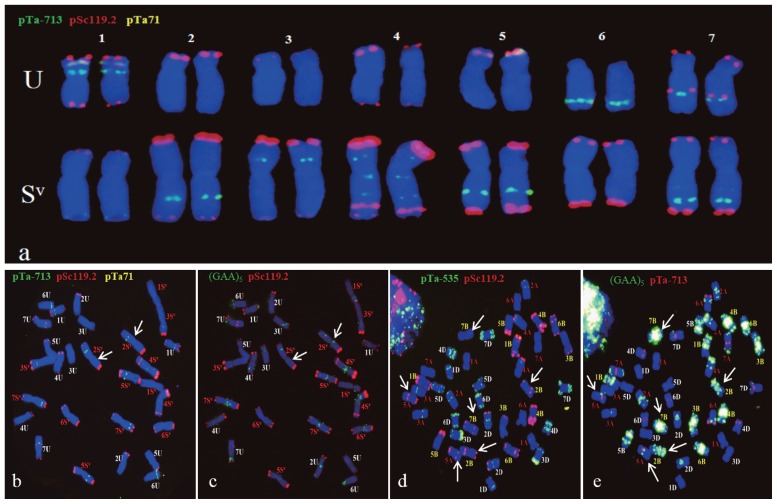

Out of six FISH probes used, (GAA)5, pSc119.2, pAs1, pTa535, pTa71, and pTa-713, (GAA)5, pSc119.2, pTa71, and pTa-713 had desirable fluorescence signals. The four probes were used to differentiate individual chromosomes of Ae. variabilis (Fig. 1a–1c). Probe pSc119.2 had fluorescence signals on U- and S-genome chromosomes except 6U, pTa71 had signals on 1U and 5U, and (GAA)5 had signals on all chromosomes of the U- and S-genomes, similar to those in corresponding chromosomes in other Aegilops species (Badaeva et al. 2004, Molnár et al. 2011, Schneider et al. 2005, Zhang et al. 2013). Most of the pTa-713 signals appeared in intermediate positions of chromosome arms, thus enhancing ability to recognise of Ae. variabilis chromosomes. The probe combination of pSc119.2, pTa71 and pTa-713 clearly differentiated all 14 pairs of Ae. variabilis chromosomes from each other (Fig. 1a, 1b).

Fig. 1.

FISH identification of parent chromosomes. (a) FISH patterns of individual Ae. variabilis chromosomes. (b, c) Ae. variabilis chromosomes from a same mitotic cell, but using different probe combinations. Arrows indicate 2Sv. (d, e) Chromosomes of common wheat Yiyuan 2 from the same mitotic cell. (d) Probes pTa535 and pSc119.2 failed to differentiate chromosomes 5A, 2B, 7B from each other (arrows). (e) Probes (GAA)5 and pTa-713 differentiated the three pairs chromosomes (arrows).

Although signals of pSc119.2 and pTa-535 can differentiate all 21 pairs of Chinese Spring chromosomes (Tang et al. 2014), signals on 5A, 2B and 7B were difficult to distinguish from each other in common wheat Yiyuan 2 (Fig. 1d). With probes pTa-713 and (GAA)5, these three chromosomes were clearly identified in Yiyuan 2 (Fig. 1e).

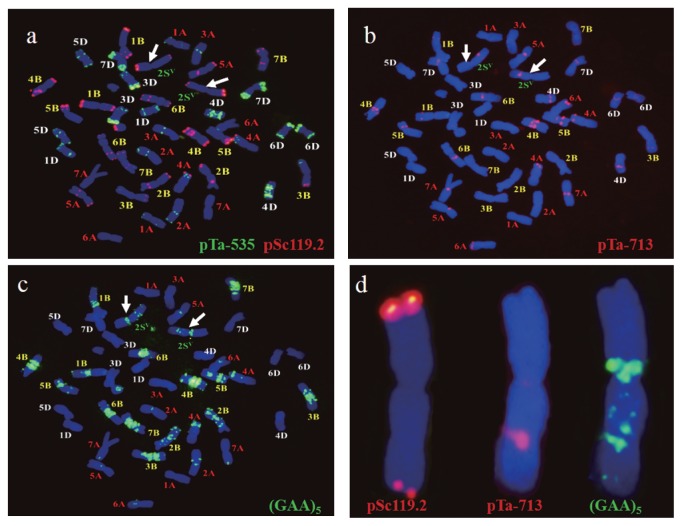

Chromosome identification of hybrid progenies

In 2014, 26 BC1F7 lines were tested for stripe rust infection. Fifteen lines exhibited resistance and 11 were susceptible. All 15 resistant lines and one randomly selected susceptible line (NZ309) were subjected to chromosome identification (Table 1). Alien chromosomes were identified in all resistant lines using pTa-535, pSc119.2, (GAA)5, and pTa-713. An example of chromosome identification in line NZ311 is shown in Fig. 2. NZ309 had 42 common normal wheat chromosomes whereas all 15 resistant lines had a pair of 2Sv chromosomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Measurement and description of agronomic traits

| Line | Chromosomes composition | Days to heading | Rust reaction | Plant heighta | Tiller no.a | Spike lengtha | Spikelet numbera | Waxinessa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| 2014 | 2015 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||

| Ae. variabilis | UUSvSv | 165 | 150 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 83.0 ± 6.1 | 131.8 ± 44.5 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | Weak |

| Yiyuan 2 | 42W | 149 | 133 | 7~9 | 7~9 | 70.7 ± 3.0 | 5.0 ± 0.7 | 7.7 ± 0.9 | 16.9 ± 2.1 | Weak |

| NZ309 | 42W | 148 | 135 | 7~9 | 7~9 | 74.6 ± 2.9 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 8.2 ± 0.6 | 19.1 ± 1.4 | Weak |

| NZ298 | 40W + II 2Sv(2B) | 158 | 146 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 81.6 ± 3.1** | 5.6 ± 1.5* | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 18.6 ± 0.8 | Weak |

| NZ300 | 40W + II 2Sv(2B) | 158 | 145 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 79.6 ± 3.5 | 5.5 ± 1.1* | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 18.8 ± 1.1 | Weak |

| NZ286 | 40W + II 2Sv(2B) 38W + II 2Sv(2B) + I 3AS·1BL + I 1BS·3AL |

159 | 144 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 86.9 ± 5.1** | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 9.3 ± 0.9* | 19.6 ± 0.8 | Weak |

| NZ292 | 40W + II 2Sv(2B) 36W + II 2Sv(2B) + II 4Sv(4B) + I 5BS·5DS + I 5BL·5DL |

158 | 146 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 74.5 ± 5.2 | 7.0 ± 1.6 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 18.7 ± 1.1 | Weak |

| NZ266 | 40W+ + II 2Sv(2B) 40W+ + II 2Sv(2B) + I 5Sv |

157 | 140 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 83.6 ± 1.9** | 6.9 ± 1.1 | 9.6 ± 1.2* | 18.6 ± 1.3 | Weak |

| NZ294 | 40W++ + II 2Sv(2B) 40W++ + II 2Sv(2B) + I 4Sv |

158 | 147 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 72.4 ± 4.9 | 5.7 ± 1.3 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 19.3 ± 0.7 | Weak |

| NZ304 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) | 166 | 158 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 97.9 ± 5.2** | 8.7 ± 2.7 | 11.8 ± 1.5** | 23.1 ± 1.7** | Strong |

| NZ307 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) | 162 | 150 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 82.3 ± 6.5** | 6.8 ± 2.4 | 10.5 ± 1.2** | 22.0 ± 2.1** | Strong |

| NZ311 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) | 164 | 152 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 93.7 ± 1.5** | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 0.6** | 21.7 ± 0.4** | Strong |

| NZ321 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) | 164 | 152 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 96.5 ± 1.2** | 6.6 ± 1.1 | 11.9 ± 0.9** | 22.2 ± 1.5** | Strong |

| NZ323 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) 40W + II 2Sv(2D) + I 4Sv |

164 | 155 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 89.6 ± 6.1** | 7.7 ± 2.3 | 11.3 ± 1.0** | 21.9 ± 1.4** | Strong |

| NZ306 | 40W + II 2Sv(2D) 40W + II 2Sv(2D) + I 4Sv |

166 | 159 | 0~1 | 0~1 | 77.5 ± 2.3 | 9.5 ± 0.9* | 11.9 ± 0.9** | 23.9 ± 1.7** | Strong |

| NZ272 | 42W+ II 2Sv + II 4Sv | 161 | 0~1 | |||||||

| NZ281 | 42W + II 2Sv + II 4Sv | 164 | 0~1 | |||||||

| NZ283 | 42W + II 2Sv + II 4Sv | 163 | 0~1 | |||||||

significantly different from common wheat line NZ309 at P = 0.05 and P = 0.01, respectively (t-test).

including one changed 6B.

including two changed 6B chromosomes.

traits measured in 2015.

Fig. 2.

Identification of alien chromosomes 2Sv from Ae. variabilis and chromosome constitution in NZ311. (a), (b) and (c) were from a same mitotic cell. (d) Chromosome 2Sv from a, b and c. Based on the signals of pSc119.2, pTa713 and (GAA)5, chromosome 2Sv (arrows) was identified in wheat background. Based on signals of pTa-535, pSc119.2, pTa713 and (GAA)5, individual wheat chromosomes were recognized.

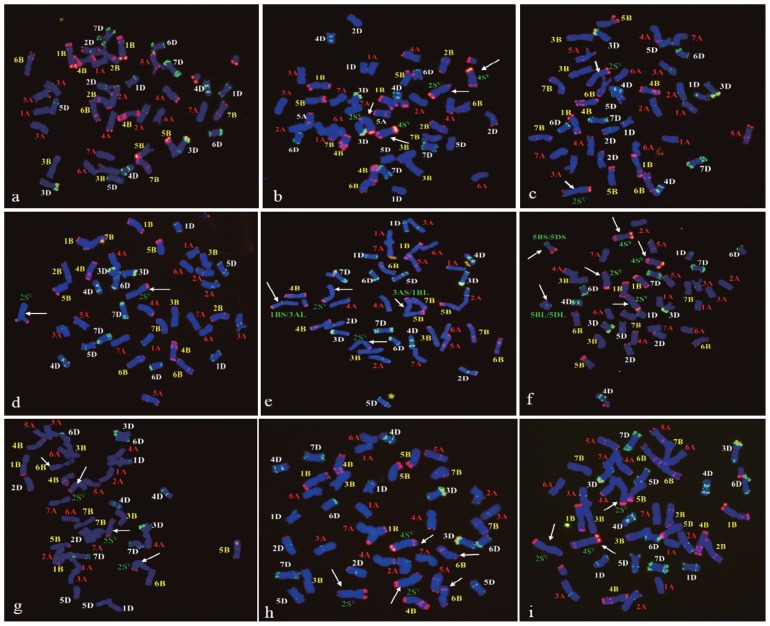

The 15 resistant lines had different chromosome constitutions. Compared to line NZ309 (Fig. 3a), three lines, NZ272 (Fig. 3b), NZ281, and NZ283, were addition lines containing two 2Sv and two 4Sv chromosomes (2n = 46). The other 12 resistant lines carried 2Sv(2B) (Fig. 3c) or 2Sv(2D) substitutions (Fig. 2, Fig. 3d). Among them, six lines (50%) showed cytological abnormalities and variable chromosome constitutions (Table 1). For instance, NZ286 had two cytotypes, 40W + II 2Sv(2B) and 38W + II 2Sv(2B) + I 3AS·1BL + I 1BS·3AL (Fig. 3e). In addition to 2Sv(2B) substitution, some cells in line NZ292 carried 5BS·5DS and 5BL·5DL translocation chromosomes (Fig. 3f); NZ266 had a changed 6B plus a 5Sv addition (Fig. 3g); and NZ294 had a pair of changed 6B chromosomes plus an added 4Sv chromosome (Fig. 3h). In addition to 2Sv(2D), some cells in lines NZ306 and NZ323 (Fig. 3i) had a 4Sv addition. This chimeric behavior was attributed to Gc gene(s) activity of chromosome 2Sv.

Fig. 3.

Chromosome constitutions of progenies. Green signals for pTa535 and red for pSc119.2, counterstained with DAPI. (a) Line NZ309 with 42 common wheat chromosomes (42W). (b) Line NZ272, 42W + II 2Sv + II 4Sv. (c) Line NZ300, 40W + II 2Sv(2B). (d) Line NZ304, 40W + II 2Sv(2D). (e) Line NZ286, 38W + II 2Sv(2B) + I 3AS·1BL + I 1BS·3AL. (f) Line NZ292, 36W + II 2Sv(2B) + II 4Sv(4B) + I 5BS·5DS + I 5BL·5DL. (g) Line NZ266, 40W+ + II 2Sv(2B) + I 5Sv. (h) Line NZ294, 40W++ + II 2Sv(2B) + I 4Sv. (i) Line NZ323, 40W + II 2Sv (2D) + I 4Sv. +, one changed 6B chromosome. ++, two changed 6B chromosomes.

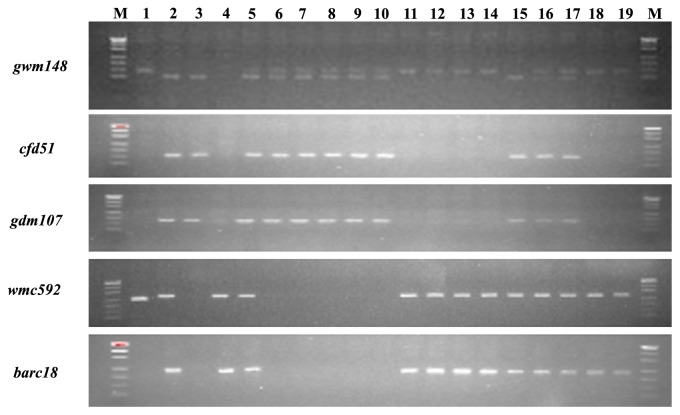

SSR confirmation of substitution lines

Of 62 SSR markers analyzed, 30 were specific to chromosome 2B or 2D as confirmed by CS NT lines, including 15 on 2B (barc55, barc18, gwm630, gwm257, gwm374, barc200, barc13, barc160, wmc257, gwm319, gwm455, cfd2278, gwm388, gwm120, and barc167) and 15 on 2D (gwm148, gdm107, gdm35, gdm77, cfd51, cfd56, cfd53, cfd77, barc159, cfd233, barc228, gpw1184, gwm320, cfd239, and gwm301). These markers showed polymorphism between Ae. variabilis and Yiyuan 2. The primers for specific markers on 2B and 2D did not amplify PCR products from the 2Sv(2B) or 2Sv(2D) substitution lines, confirming absence of 2B or 2D (Fig. 4). Marker gwm148 was amplified as co-dominant bands from 2D and 2Sv, the band from 2Sv was easily differentiated by size from that of 2D (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

PCR amplification patterns generated by SSR markers. M 500 bp marker, 1 Ae. variabilis, 2 Yiyuan 2, 3 N2BT2D, 4 N2DT2B, 5 NZ272, 6 NZ266, 7 NZ286, 8 NZ292, 9 NZ294, 10 NZ298, 11NZ304, 12 NZ306, 13 NZ307, 14 NZ311, 15 NZ309, 16 NZ281, 17 NZ283, 18 NZ321, 19 NZ323. 5, 16 and 17 were 2Sv addition lines; 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10, 2Sv(2B) substitution lines; 11, 12, 13, 14, 18 and 19, 2Sv(2D) substitution lines; 15 common wheat without an alien chromosome. Markers gwm148, cfd51 and gdm107 were the specific markers for 2D; markers wmc592 and barc18 were specific for 2B.

Evaluation of agronomic traits

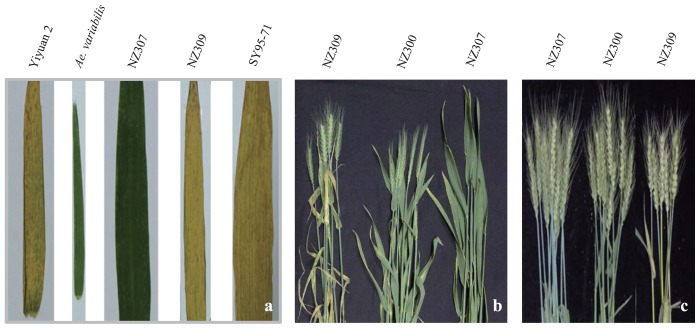

The stripe rust resistance was evaluated in both 2014 and 2015 by inoculation with mixed urediospores. Yiyuan 2 was highly susceptible whereas Ae. variabilis was resistant (Fig. 5a). The 15 derivatives with 2Sv all exhibited resistance (infection type 0–1) whereas line NZ309 lacking 2Sv was susceptible (7–9) (Fig. 5a, Table 1). This result indicated that a resistance gene(s) was present on chromosome 2Sv.

Fig. 5.

Field performances. (a) Stripe rust responses on flag leaves. Ae. variabilis AS116 and NZ307 (2Sv(2D)) were resistant; NZ309 and YY2 were susceptible. Wheat SY95-71 was the disease spreader. (b) NZ309 showed earlier heading than NZ307 (2Sv(2D)) and NZ300 (2Sv(2B)). (c) NZ309 and NZ300 (2Sv(2B)) were weakly waxy, whereas NZ307 (2Sv(2D)) was strongly waxy.

Ae. variabilis cytoplasm had effects on agronomic traits compared to its wheat parent, for example, line NZ309 had significantly more tillers than Yiyuan 2. Compared to NZ309 the 2Sv(2D) and 2Sv(2B) substitution lines of exhibited delayed heading, with 2Sv(2D) lines generally being later (Table 1, Fig. 5b). The difference between 2Sv(2D) and 2Sv(2B) indicated that deletion of the 2D and 2B chromosomes had different effects on heading time.

The 12 BC1F8 2Sv(2D) or 2Sv(2B) lines were evaluated for plant height, number of tillers, main spikelet length, main spikelet number, and plant waxiness. Compared to NZ309, 2Sv(2B) was less affected than 2Sv(2D). The 2Sv(2D) substitution lines were taller, and had more spikelets and longer spikes (Table 1). The loss of 2B and 2D caused different effects on waxiness. Ae. variabilis, Yiyuan 2, NZ309 and the 2Sv(2B) substitution line were weakly waxy, but the 2Sv(2D) substitution line was strongly waxy (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Alien genetic resources are important for improving agronomic traits in wheat. The identification of alien chromosomes in wheat backgrounds is a critical step in utilizing alien genetic resources. FISH probes of repetitive sequences, such as pAs1, pSc119.2, pTa71, pTa-86, and pTa-535, have been widely used to identify individual chromosomes of the wheat A-, B-, and D-genomes (Hao et al. 2013, Komuro et al. 2013, Langridge 1997, Pedersen and Sepsi et al. 2008). FISH technology has been also used for chromosome identification in Aegilops species, including U- or/and S-genome chromosomes (Badaeva et al. 2004, Kwiatek et al. 2013, Molnár et al. 2011, Salina et al. 2006, Schneider et al. 2005, Zhang et al. 2013). However, the fluorescence signals of most probes appear in terminal regions, leading to uncertain identification of alien U- and S-chromosomes of Ae. variabilis, especially in wheat backgrounds. In this study we found that most of the pTa-713 signals were in the middle regions of chromosome arms, allowing better identification and easier identification of chromosomes from Ae. variabilis. The probe combination of pSc119.2, pTa71 and pTa-713 easily differentiated all 14 pairs of Ae. variabilis chromosomes. In addition, the co-dominant SSR marker gwm148 can be used in tracing chromosome 2Sv in common wheat background (Fig. 4).

Liu et al. (2011) reported transfer of stripe rust resistance from Ae. variabilis accession 13E to wheat, but the chromosome location of the gene(s) was unknown. The present study shows that resistance from Ae. variabilis accession AS116 is in chromosome 2Sv. It is unclear whether the genes from the two accessions are the same. The gene on 2Sv must now be transferred to wheat before it can be used in breeding. This should be possible through the use of a ph1 genetic stock to allow chromosome 2Sv to synapse and recombine with a wheat homoeolog.

Photoperiod affects both vegetative and reproductive development in wheat (Miralles et al. 2000). The strongest genes affecting photoperiod response in wheat and presumably closely related species are located in Group II chromosomes. Ppd-D1 on 2D is the most photoperiod insensitive locus followed by Ppd-B1 on 2B and Ppd-A1 on 2A (Worland 1996). In this study, 2Sv(2D) substitution lines were later flowering than 2Sv(2B) lines and euploid wheat. The extended growth period of the 2Sv(2D) line may have caused more spikelets and longer spikes. In addition, 2Sv(2D) or 2Sv(2B) lines affected other agronomic traits, such as waxiness and plant height.

Chromosome structural aberrations, including non-homologous translocations, were observed at relatively high frequency in a number of lines. This may be due to the presence of so-called gametocidal genes that have been reported in various 2S chromosomes (Endo 1985, 1990, Knight et al. 2015, Kota and Dvorak 1988, Miller et al. 1982, Tsujimoto 2005). There are Gc genes on S-genome chromosomes, such as 2S and 6S of Ae. speltoides, 2Sl and 4Sl of Ae. longissima, 2Ssh and 4Ssh of Ae. sharonensis. Ae. longissima is the S-genome donor species of Ae. variabilis (Kihara 1954, Yu and Jahier 1992). Hence Ae. variabilis may have inherited Gc gene(s) from Ae. longissima. Although wheat lines with 2Sv or 4Sv can be used as tools to induce novel chromosome structural rearrangements, this is not the preferred method as such recombination events appear to be random and therefore less likely to be compensatory.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Robert A. McIntosh, at University of Sydney, for revising this manuscript. This research was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of the Education Department of Sichuan Province (14ZA0012), the Sichuan Provincial Human Resources and Social Security Department Foundation (03109146), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31271723).

Literature Cited

- Badaeva, E.D., Amosova, A.V., Samatadze, T.E., Zoshchuk, S.A., Shostak, N.G., Chikida, N.N., Zelenin, A.V., Raupp, W.J., Friebe, B. and Gill, B.S. (2004) Genome differentiation in Aegilops. 4. Evolution of the U-genome cluster. Plant Syst. Evol. 246: 45–76. [Google Scholar]

- Barloy, D., Lemoine, J., Abelard, P., Tanguy, A.M., Rivoal, R. and Jahier, J. (2007) Marker-assisted pyramiding of two cereal cyst nematode resistance genes from Aegilops variabilis in wheat. Mol. Breed. 20: 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.Q., Wu, L.R., Liu, T.G., Xu, S.C., Jin, S.L., Peng, Y.L. and Wang, B.T. (2009) Race dynamics, diversity, and virulence evolution in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, the causal agent of wheat stripe rust in China from 2003 to 2007. Plant Dis. 93: 1093–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.M. (2005) Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici] on wheat. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 27: 314–337. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, A., Cardoso, M. and Jouve, N. (2008) Increasing the physical markers of wheat chromosomes using SSRs as FISH probes. Genome 51: 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, E.S., Gerlach, W.L. and Peacock, W.J. (1980) Identical polypyrimidine-polypurine satellite DNAs in wheat and barley. Heredity 44: 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, T.R. (1985) Two types of gametocidal chromosomes of Aegilops sharonensis and Ae. longissima. Jpn. J. Genet. 60: 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, T.R. (1990) Gametocidal chromosomes and their induction of chromosome mutations in wheat. Jpn. J. Genet. 65: 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, M., Luo, J.T., Yang, M., Zhang, L.Q., Yan, Z.H., Yuan, Z.W., Zheng, Y.L., Zhang, H.G. and Liu, D.C. (2011) Comparison of homoeologous chromosome pairing between hybrids of wheat genotypes Chinese Spring ph1b and Kaixian-luohanmai with rye. Genome 54: 959–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, M., Luo, J.T., Zhang, L.Q., Yuan, Z.W., Yang, Y.W., Wu, M., Chen, W.J., Zheng, Y.L., Zhang, H.G. and Liu, D.C. (2013) Production of hexaploid triticale by a synthetic hexaploid wheat–rye hybrid method. Euphytica 193: 347–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, A. (1999) Air drying method using nitrous oxide for chromosome counting in maize. Biotech. Histochem. 74: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara, H. (1944) Discovery of the DD-analyser, one of the ancestors of Triticum vulgare. Agric. Hortic. 19: 889–890. [Google Scholar]

- Kihara, H. (1954) Considerations on the evolution and distribution of Aegilops species based on the analyser-method. Cytologia 19: 336–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kilian, B., Ozkan, H., Deusch, O., Effgen, S., Brandolini, A., Kohl, J., Martin, W. and Salamini, F. (2007) Independent wheat B and G genome origins in outcrossing Aegilops progenitor haplotypes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, E., Binnie, A., Draeger, T., Moscou, M.D., Rey, M., Sucher, J., Mehra, S., King, I. and Moore, G. (2015) Mapping the ‘breaker’ element of the gametocidal locus proximal to a block of sub-telomeric heterochromatin on the long arm of chromosome 4Ssh of Aegilops sharonensis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128: 1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komuro, S., Endo, R., Shikata, K. and Kato, A. (2013) Genomic and chromosomal distribution patterns of various repeated DNA sequences in wheat revealed by a fluorescence in situ hybridization procedure. Genome 56: 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota, R.S. and Dvorak, J. (1988) Genomic instability in wheat induced by chromosome 6BS of Triticum speltoides. Genetics 120: 1085–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatek, M., Wiśniewska, H. and Apolinarska, B. (2013) Cytogenetic analysis of Aegilops chromosomes, potentially usable in triticale (X Triticosecale Witt.) breeding. J. Appl. Genet. 54: 147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.C., Xiang, Z.G., Zhang, L.Q., Zheng, Y.L., Yang, W.Y., Chen, G.Y., Wan, C.J. and Zhang, H.G. (2011) Transfer of stripe rust resistance from Aegilops variabilis to bread wheat. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10: 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., Chang, Z.J., Zhang, X.J., Yang, Z.J., Li, X., Jia, J.Q., Zhan, H.X., Guo, H.J. and Wang, J.M. (2013) Putative Thinopyrum intermedium derived stripe rust resistance gene Yr50 maps on wheat chromosome arm 4BL. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.G., Peng, Y.L., Chen, W.Q. and Zhang, Z.Y. (2010) First detection of virulence in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China to resistance genes Yr24 (=Yr26) present in wheat cultivar Chuanmai 42. Plant Dis. 94: 1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais, G.F., McCallum, B. and Marais, A.S. (2008) Wheat leaf rust resistance gene Lr59 derived from Aegilops peregrina. Plant Breed. 127: 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, E.S. and Sears, E.R. (1944) The artificial synthesis of Triticum spleta. Rec. Genet. Soc. Am. 13: 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- McNeal, F.H., Koznak, C.F., Smith, E.P., Tate, W.S. and Russell, T.S. (1971) A uniform system for recording and processing cereal research data. USDA-ARS Bull. 42: 34–121. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T.E., Hutchinson, J. and Chapman, V. (1982) Investigation of a preferentially transmitted Aegilops sharonensis chromosome in wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 61: 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miralles, D.J., Richards, R.A. and Slafer, G.A. (2000) Duration of stem elongation period influences the number of fertile florets in wheat and barley. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 27: 931–940. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, I., Cifuentes, M., Schneider, A., Benavente, E. and Molnár-Láng, M. (2011) Association between simple sequence repeat-rich chromosome regions and intergenomic translocation breakpoints in natural populations of allopolyploid wild wheats. Ann. Bot. 107: 65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujeeb-Kazi, A., Gul, A., Farooq, M., Rizwan, S. and Mirza, J.I. (2007) Genetic diversity of Aegilops variabilis (2n = 4x = 28; UUSS) for wheat improvement: morpho-cytogentic characterization of some derived amphiploids and their practical significance. Pak. J. Bot. 39: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Neelam, K., Rawat, N., Tiwari, V.K., Kumar, S., Chhuneja, P., Singh, K., Randhawa, S. and Dhaliwal, H.S. (2011) Introgression of group 4 and 7 chromosomes of Ae. peregrina in wheat enhances grain iron and zinc density. Mol. Breed. 28: 623–634. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, C. and Langridge, P. (1997) Identification of the entire chromosome complement of bread wheat by two-colour FISH. Genome 40: 589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, G., Seberg, O., Yde, M. and Berthelsen, K. (2006) Phylogenetic relationships of Triticum and Aegilops and evidence for the origin of the A, B, and D genomes of common wheat (Triticum aestivum). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 39: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salina, E.A., Lim, K.Y., Badaeva, E.D., Shcherban, A.B., Adonina, I.G., Amosova, A.V., Samatadze, T.E., Vatolina, T.Y., Zoshchuk, S.A. and Leitch, A.R. (2006) Phylogenetic reconstruction of Aegilops section Sitopsis and the evolution of tandem repeats in the diploids and derived wheat polyploids. Genome 49: 1023–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A., Linc, G., Molnár, I. and Molnár-Láng, M. (2005) Molecular cytogenetic characterization of Aegilops biuncialis and its use for the identification of 5 derived wheats – Aegilops biuncialis disomic addition lines. Genome 48: 1070–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears, E.R. (1976) Genetic control of chromosome pairing in wheat. Annu. Rev. Genet. 10: 31–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepsi, A., Molnár, I., Szalay, D. and Molnár-Láng, M. (2008) Characterization of a leaf rust-resistant wheat–Thinopyrum ponticum partial amphiploid BE-1, using sequential multicolor GISH and FISH. Theor. Appl. Genet. 116: 825–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sourdille, P., Singh, S., Cadalen, T., Brown-Guedira, G.L., Gay, G., Qi, L.L., Gill, B.S., Dufour, P., Murigneux, A. and Bernard, M. (2004) Microsatellite-based deletion bin system for the establishment of genetic-physical map relationships in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Funct. Integr. Genomics 4: 12–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spetsov, P., Mingeot, D., Jacquemin, J.M., Samardjieva, K. and Marinova, E. (1997) Transfer of powdery mildew resistance from Aegilops variabilis into bread wheat. Euphytica 93: 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.X., Yang, Z.J. and Fu, S.L. (2014) Oligonucleotides replacing the roles of repetitive sequences pAs1, pSc119.2, pTa-535, pTa71, CCS1, and pAWRC.1 for FISH analysis. J. Appl. Genet. 55: 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto, H. (2005) Gametocidal genes in wheat as the inducer of chromosome breakage. In: Tsunewaki, K. (ed.) Frontiers of Wheat Bioscience. Memorial issue, Wheat Information Service No. 100 Kihara Memorial Yokohama Foundation, Yokohama, pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- van Slageren, M.W. (1994) Wild wheats: a monograph of Aegilops L. and Amblyopyrum (Jaub. & Spach) Eig (Poaceae). Agricultural University, Wageningen; International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas, Aleppo, Syria. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, A., Zhao, Z., Chen, X., He, Z., Jin, S., Jia, Q., Yao, G., Yang, J., Wang, B., Li, G.et al. (2004) Wheat stripe rust epidemic and virulence of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. Tritici in China in 2002. Plant Dis. 88: 896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan, A.M., Chen, X.M. and He, Z.H. (2007) Wheat stripe rust in China. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 58: 605–619. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.R. and Lu, B. (2014) Biosystematics and evolutionary relationships of perennial Triticeae species revealed by genomic analyses. J. Syst. Evol. 52: 697–705. [Google Scholar]

- Worland, A. (1996) The influence of flowering time genes on environmental adaptability in European wheats. Euphytica 89: 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, C., Yang, J.L. and Yen, Y. (2005) Hitoshi Kihara, Askell Löve and the modern genetic concept of the genera in the tribe Triticeae (Poaceae). Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 43: 82–93. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, C. and Yang, J.L. (2009) Historical review and prospect of taxonomy of tribe Triticeae Dumortier (Poaceae). Breed. Sci. 59: 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.Q., Person-Dedryver, F., Jahier, J., Pannetier, D., Tanguy, A.M. and Abelard, P. (1990) Resistance to root knot nematode, Meloidogyne naasi (Franklin) transferred from Aegilops variabilis Eig to bread wheat. Agronomie 6: 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.Q. and Jahier, J. (1992) Origin of Sv genome of Aegilops variabilis and utilization of the Sv as analyser of the S genome of the Aegilops species in the Sitopsis section. Plant Breed. 108: 290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.Q., Jahier, J. and Person-Dedryver, F. (1992) Genetics of two mechanisms of resistance to Meloidogyne naasi (FRANKLIN) in an Aegilops variabilis Eig. Accession. Euphytica 58: 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H., Bian, Y., Gou, X.W., Dong, Y.Z., Rustgi, S., Zhang, B.J., Xu, C.M., Li, N., Qi, B., Han, F.P.et al. (2013) Intrinsic karyotype stability and gene copy number variations may have laid the foundation for tetraploid wheat formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 110: 19466–19471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]