Abstract

Alpha-tocopherol is one of four tocopherol isoforms and has the highest vitamin E activity in humans. Most cultivated soybean seeds contain γ-tocopherol as the predominant form, and the ratio of α-tocopherol content to total tocopherol content (α-tocopherol ratio) is <10%. Three soybean accessions from Eastern Europe have α-tocopherol ratios of >20%. This higher content is likely due to mutations in the promoter region of the γ-tocopherol methytransferase-3 (γ-TMT3) gene. We surveyed a wild soybean germplasm collection and detected 16 accessions with stable seed α-tocopherol ratios of >20% under different growth conditions. The α-tocopherol ratios were greatly reduced when the plants were grown under cool temperatures during seed maturation, but increased to varying degrees at higher temperatures. Sequence analysis of the γ-TMT3 promoter of 11 of the accessions identified four haplotypes, one of which corresponded to that of cultivars with higher contents. These wild accessions can thus serve as novel donors for breeding cultivars with high α-tocopherol ratios and for better understanding the genetic basis of α-tocopherol synthesis in soybean.

Keywords: soybean, Glycine max, wild germplasm, genetic diversity, nutraceutical, functional food, vitamin E

Introduction

Alpha-tocopherol is the tocopherol isoform that has the highest vitamin E activity in human (DellaPenna 2005). Soybean seeds contain relatively high total tocopherol content, but a ratio of α-tocopherol content to the total tocopherol content (hereinafter referred to as α-tocopherol ratio) is <10%, and therefore vitamin E activity is lower than that of other oilseed crops (Bramley et al. 2000). Enhancing the α-tocopherol ratio would thus increase the nutritional and market value of soybean as a functional food.

From a survey of 909 accessions in a worldwide cultivated soybean germplasm collection, Ujiie et al. (2005) discovered three accessions from Eastern Europe, Keszthelyi Aprosezmu Sarga (KAS), Dobrudza 14 Pancevo, and Dobrogeance, which had the α-tocopherol ratios of >20%. The trait was stable across planting years (Ujiie et al. 2005). QTL mapping using an F2 segregating population derived from a cross between a Japanese cultivar, Ichihime (α-tocopherol ratio <10%), and KAS detected a major QTL on chromosome 9 which controls the elevated ratio in KAS (Dwiyanti et al. 2007). Fine mapping and gene cloning revealed γ-tocopherol methytransferase-3 (γ-TMT3) as a candidate gene (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Gamma-tocopherol methyltransferase is the enzyme in the last step of tocopherol biosynthesis, in which it converts γ-tocopherol to α-tocopherol and δ-tocopherol to β-tocopherol (DellaPenna 2005). Gene annotation of the Williams 82 soybean reference genome (Schmutz et al. 2010) identifies γ-TMT3 (Glyma.09G222800) as one of three γ-TMT genes present in the soybean genome. γ-TMT3 is located on chromosome 9, whereas γ-TMT1 (Glyma.12G014200) and γ-TMT2 (Glyma.12G014300) are located in tandem on chromosome 12 (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Overexpression of γ-TMT2 in corn (maize) and Arabidopsis increased their α-tocopherol contents, indicating that γ-TMT2 is functional (Zhang et al. 2013).

During seed maturation, γ-TMT3 expression was higher in seeds of recombinant inbred lines (RILs) with the KAS allele of γ-TMT3 than in the seeds of RILs with the Ichihime allele (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Furthermore, GUS-assay analysis confirmed that the activity of the KAS γ-TMT3 promoter is higher than that of the Ichihime promoter (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Comparison of γ-TMT3 promoter sequences between the high-α-tocopherol cultivars (KAS, Dobrudza 14 Pancevo, and Dobrogeance) and standard Japanese cultivars with low α-tocopherol ratios (Ichihime and Toyokomachi) showed that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in MYBCORE and CAAT box motifs in the promoter region are likely responsible for the elevated ratio (Dwiyanti et al. 2011).

Wild soybean germplasm is a huge reservoir of potential donors for beneficial traits that can be used to improve existing cultivars. Alleles from wild soybean have been used to improve yield, stress tolerance, disease resistance, and nutritional components of cultivated soybean (Concibido et al. 2003, Kim et al. 2010, Wang et al. 2007, Xu and Tuyen 2012). In this study, we aimed at tapping the genetic diversity in wild soybean germplasm collected from various regions in Japan and South Korea to find novel genetic resources that can be used in breeding of high-α-tocopherol soybean.

Environmental factors during seed maturation such as warm temperature and drought are known to enhance seed α-tocopherol content to 2 or 3 times the normal level (Almonor et al. 1998, Britz and Kremer 2002, Britz et al. 2008). Conversely, soybeans grown in cooler environments had a lower α-tocopherol content (Seguin et al. 2010). Since it is important to breed cultivars that produce seeds with stably high α-tocopherol contents across different growing conditions, we evaluated the thermo-sensitivity of α-tocopherol ratios in seeds of wild accessions with high α-tocopherol ratios. We also sequenced the γ-TMT3 promoter region to determine whether the selected wild accessions have the same promoter sequence as KAS. This information will be useful in selecting new donors to breed high-α-tocopherol soybeans.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

We analyzed the seed α-tocopherol contents of 528 wild soybean accessions collected in or introduced from various regions in Japan and South Korea. Thirty-three accessions were collected in Hokkaido, 144 in Tohoku, 58 in Hokuriku, 51 in Kanto, 40 in Tokai/Kinki, 84 in Shikoku, 25 in Chugoku, 19 in Kyushu, and 74 in South Korea (Supplemental Table 1). The Japanese accessions are available via LegumeBase (https://www.legumebase.brc.miyazaki-u.ac.jp/), an integrated resource database of Lotus japonicus and Glycine max. The seeds assayed were those collected individually or in bulk from four to six plants in natural habitats.

Accessions with α-tocopherol ratios of >20%, together with KAS as a control, were grown in glasshouses or polyhouses at Hokkaido University from 2010 to 2011. The seeds were harvested individually and reassayed. We finally selected 16 accessions as novel sources of elevated α-tocopherol ratios. The seeds harvested from a single plant were used for the temperature effect experiment and sequence analysis. We analyzed the promoter sequences of γ-TMT3 in 11 of those accessions.

Temperature effect experiment

Three or four plants per accession per temperature regime were raised in a Wagner pot (16-cm diameter) with a nursery soil (Katakura & Co-op Agri Cooperation, Japan) in glasshouses at Hokkaido University. The temperature treatment was carried out without replications. After flowering, pots were transferred to growth chambers where the temperature was maintained at constant temperatures of 20, 25, or 30°C until seed maturation. The mature seeds were harvested in bulk and were dried for 2 days at 80°C before analysis.

Tocopherol quantification

The tocopherol contents of the seeds (without a seed coat) were quantified according to Wang et al. (2007): 40 mg of seed powder was thoroughly mixed with 500 μL of cold acetone (4°C) containing dl-Tocol (3 μg/ml; Tama Biochemical Co. Ltd., Japan) as an internal standard. After sonication for 20 min, the mixture was held at 4°C for 30 min. It was then centrifuged for 15 min at 13 000 rpm, 4°C. The supernatants were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography (LaChrom Elite, Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Japan) using a reverse-phase column (Inertsil ODS-3, 4.6 mm × 250 mm, GL Sciences, Japan) with an ethyl acetate: 75% methanol (50:50 v/v) mobile phase at 0.8 mL/min at a constant 40°C. Tocopherol isoforms were detected at 295 nm, and α-tocopherol ratio was calculated as the ratio of α-tocopherol peak area to a sum of α-, γ- and δ-tocopherol peak areas. The γ-tocopherol peak area is a sum of β- and γ-tocopherol areas, because the peak of β-tocopherol overlapped with the γ-tocopherol peak. The assay was carried out by three replications.

Sequence analysis of the γ-TMT3 promoter region

Total DNA was extracted from leaves of the 11 accessions according to the procedure of Doyle and Doyle (1987). The γ-TMT3 promoter region (1,350 bp) was amplified by PCR using the primers 5′-CTAAGAGCCATCTTGTCTCCACTC-3′ and 5′-GTAGTCCATTTCATGTGGTGCTGG-3′ and KOD Plus reagents following the manufacturer’s protocol (Toyobo, Japan). The PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT reagent (Affymetrix, Japan), and were sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The primers used for sequencing are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

Results

Survey of α-tocopherol contents of wild soybean germplasm collection

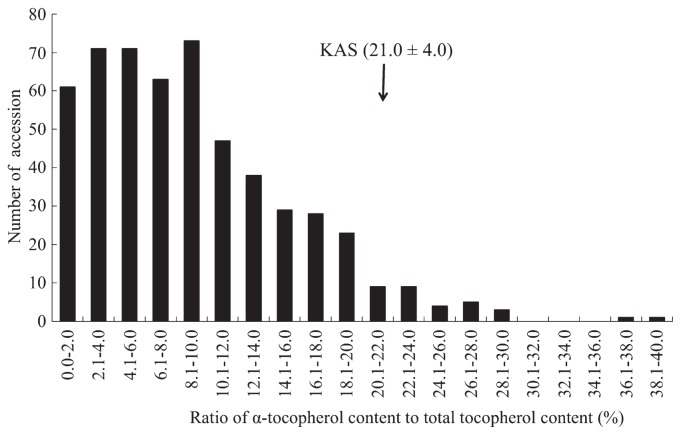

The seed α-tocopherol ratio of the 528 wild soybean accessions varied widely, from <2% to ≥38% (Fig. 1). Thirty-two accessions had α-tocopherol ratios of >20%. Since the seeds used in initial screening came from various environments, we grew these accessions with KAS as controls from 2010 to 2011, and reassayed their α-tocopherol ratios. The α-tocopherol ratio of KAS averaged 21% (Fig. 1). We finally selected 16 accessions that showed α-tocopherol ratios of >20% under the Hokkaido environment: two (B00090 and B00092) from South Korea, three (B09069, B09092 and B09117) from Kyushu, one (B07161) from Shikoku, five (B06065, B06081, B08034, B08040 and B08045) from southern Honshu, and five (B02268, B04009, B04025, B04158 and B05023) from central Honshu (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Variation in seed α-tocopherol ratios of wild soybean germplasms.

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of 16 wild soybean accessions with high seed α-tocopherol ratios.

Effect of temperature during seed maturation on α-tocopherol ratios

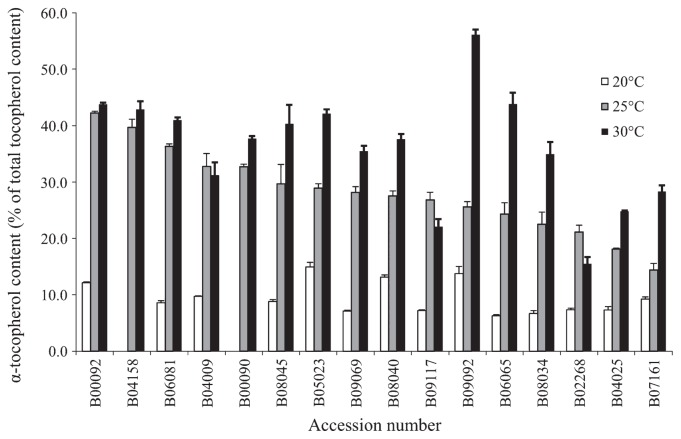

We next evaluated the variation of α-tocopherol ratios among the 16 accessions at three consistent thermal conditions. When the seeds were matured at 25°C, the α-tocopherol ratios of the 16 accessions tested varied widely, from 14.4% (B07161) to 42.3% (B00092) (Fig. 3). However, at 20°C, most accessions had ratios of <10%, and only four accessions (B00092, B05023, B08040 and B09092) had ratios of between 10% and 15%.

Fig. 3.

Effects of temperature during seed maturation on mean α-tocopherol ratios.

When seeds were matured at 30°C, on the other hand, the α-tocopherol ratios increased in most accessions, and the rates of increase varied widely among the accessions. Most accessions produced higher α-tocopherol ratios at 30°C; that in B09092 was more than double that at 25°C. In contrast, two accessions showed only small increases (B00092 and B04158), one showed a small decrease (B04009), and two showed decreases of 18% and 27% (B02268 and B09117; Fig. 3).

Haplotypes of the γ-TMT3 promoter sequence of high α-tocopherol accessions

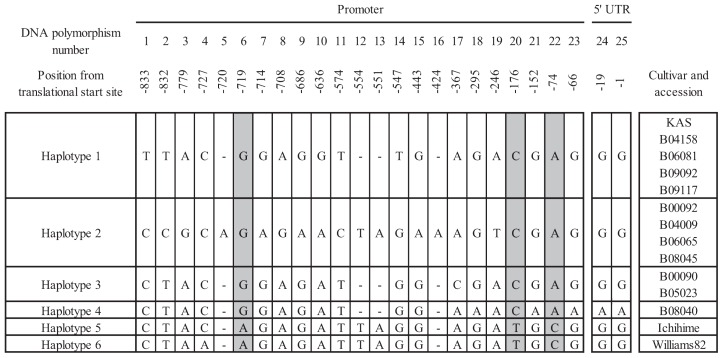

Since nucleotide polymorphisms in the γ-TMT3 promoter may play an important role in the greater α-tocopherol ratio of KAS (Dwiyanti et al. 2011), we analyzed 1,350 bp covering the promoter and 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the 11 accessions with the highest α-tocopherol ratios to determine whether they had the same promoter sequence as KAS. We found a total of 21 SNPs and 4 indels between the 11 accessions and the 3 cultivars (KAS, Ichihime, and Williams 82). On the basis of the polymorphisms, we could classify the 11 accessions into 4 haplotypes (Fig. 4). Accessions B04158, B06081, B09092, and B09117 had Haplotype 1, the same as KAS. Accessions B00092, B04009, B06065, and B08045 had Haplotype 2, which differed from Haplotype 1 in 11 SNPs and 4 indels. Accessions B00090 and B05023 had Haplotype 3, which differed from Haplotype 1 in 4 SNPs. Accession B08040 had Haplotype 4, which differed from Haplotype 1 in 6 SNPs in the promoter region and 2 SNPs in the 5′ UTR (Fig. 4). These haplotypes did not correspond to either the regions where the accessions were collected (Fig. 1) or the responses to temperature during seed maturation (Fig. 3). Among all SNPs, three SNPs located at 719 bp (#6), 176 bp (#20), and 74 bp (#22) upstream of the translational start site differentiated KAS and the 11 wild accessions from Ichihime (Haplotype 5) and Williams 82 (Haplotype 6) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Polymorphism of DNA sequences in the promoter and 5′ UTR regions of γ-TMT3 among 11 wild accessions with high seed α-tocopherol ratios. Williams 82 (AB617799) and Ichihime (AB617792) are standard cultivars with low α-tocopherol ratios. The wild accessions were classified into four haplotypes (1 to 4) on the basis of sequence variations.

Discussion

Among 909 cultivated soybean accessions, Ujiie et al. (2005) found three Eastern European soybean cultivars with high α-tocopherol ratios. Among the 528 wild soybean accessions tested in this study, we found 32 accessions with α-tocopherol ratios of >20%, 16 of which also exhibited high α-tocopherol ratios in propagated seeds. The proportion of wild accessions with high α-tocopherol ratios (16/528) was thus higher than that of cultivated soybean accessions (3/909, Ujiie et al. 2005), suggesting that wild soybean has large potential as high-α-tocopherol donor.

It is important to breed cultivars that produce seeds with stably high α-tocopherol ratios across different growing conditions, since the temperature during seed maturation influences its content (Almonor et al. 1998, Britz and Kremer 2002, Britz et al. 2008, Seguin et al. 2010). The selected accessions had different sensitivities to temperature during maturation. The α-tocopherol ratios of all 16 accessions were the lowest when seeds were matured at 20°C, but increased by different degrees when matured at 25 and 30°C. The responses, in particular those from 25 to 30°C, varied widely. Accession B09092 had the highest α-tocopherol ratio when matured at 30°C (56.1%), double that at 25°C (25.6%). On the other hand, accessions B00092, B04158, and B04009 showed little change in ratios between 25 and 30°C. Therefore, these wild accessions may use different mechanisms to control the seed α-tocopherol ratio in response to temperature during seed maturation. It will be of interest to determine the genetic factors underlying these different thermo-sensitivities among the accessions.

The high α-tocopherol ratio of KAS is caused by high γ-TMT3 promoter activity, likely due to SNPs in the MYBCORE and CAAT box motifs in the promoter (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). In the promoter sequences of four of the accessions, we found the same promoter sequence as in KAS, indicating that this promoter sequence occurs also in wild germplasm. The other accessions had different sequences. However, three SNPs differentiated both cultivated and wild high-α-tocopherol accessions from standard low-α-tocopherol cultivars. Of these, SNP #6 in the CAAT box has previously been reported to differentiate KAS from standard low-α-tocopherol cultivars (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Two newly detected SNPs, #20 and #22, may be considered additional diagnostic SNPs for high α-tocopherol ratio. Increased activities in enzymes, such as γ-TMT3 and the other homologs (γ-TMT1 and γ-TMT2) and/or other enzymes involved in the tocopherol biosynthesis pathway, may be involved in the generation of higher α-tocopherol ratios in seeds. Further studies are thus needed to determine whether the high α-tocopherol ratios of wild accessions with different promoter sequences from those of KAS are controlled by genes other than γ-TMT3, and whether the three SNPs contribute to a high promoter activity (Dwiyanti et al. 2011). Genetic analyses using test crossings, QTL mapping, and gene cloning will be needed to determine the causes of high α-tocopherol ratios in the wild soybean accessions. The accessions identified here will be useful in not only breeding high-α-tocopherol soybean but also better understanding the mechanisms of tocopherol synthesis in soybean.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a “Lotus and Glycine” National Bioresources Project and by the Fuji Foundation. We used the DNA sequencing facility of Research Faculty of Agriculture, Hokkaido University.

Footnotes

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ data libraries under the following accession number: B09092 g-TMT3 promoter (Haplotype 1) (LC122684), B04009 g-TMT3 promoter (Haplotype 2) (LC122681), B05023 g-TMT3 promoter (Haplotype 3) (LC122682), and B08040 g-TMT3 promoter (Haplotype 4) (LC122683).

Literature Cited

- Almonor, G.O., Fenner, G.P. and Wilson, R.F. (1998) Temperature effects on tocopherol composition in soybeans with genetically improved soy oil quality. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 75: 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Bramley, P.M., Elmadfa, I., Kafatos, A., Kelly, F.J., Manios, Y., Roxborough, H.E., Schuch, W., Sheehy, P.J.A. and Wagner, K.-H. (2000) Vitamin E. J. Sci. Food Agric. 80: 913–938. [Google Scholar]

- Britz, S.J. and Kremer, D.F. (2002) Warm temperatures or drought during seed maturation increase free α-tocopherol in seeds of soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 50: 6058–6063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britz, S.J., Kremer, D.F. and Kenworthy, W.J. (2008) Tocopherols in soybean seeds: genetic variation and environmental effects in field-grown crops. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 85: 931–936. [Google Scholar]

- Concibido, V., La Vallee, B., Mclaird, P., Pineda, N., Meyer, J., Hummel, L., Yang, J., Wu, K. and Delannay, X. (2003) Introgression of a quantitative trait locus for yield from Glycine soja into commercial soybean cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DellaPenna, D. (2005) Progress in the dissection and manipulation of vitamin E synthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 10: 574–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, J.J. and Doyle, J.L. (1987) A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dwiyanti, M.S., Ujiie, A., Thuy, L.T.B., Yamada, T. and Kitamura, K. (2007) Genetic analysis of high α-tocopherol content in soybean seeds. Breed. Sci. 57: 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dwiyanti, M.S., Yamada, T., Sato, M., Abe, J. and Kitamura, K. (2011) Genetic variation of γ-tocopherol methyltransferase gene contributes to elevated α-tocopherol content in soybean seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 11: 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., Hyten, D.L., Niblack, T.L. and Diers, B.W. (2010) Stacking resistance alleles from wild and domestic soybean sources improves soybean cyst nematode resistance. Crop Sci. 51: 934–943. [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz, J., Cannon, S.B., Schlueter, J., Ma, J., Mitros, T., Nelson, W., Hyten, D.L., Song, Q., Thelen, J.J., Cheng, J.et al. (2010) Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463: 178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin, P., Tremblay, G., Pageau, D. and Liu, W. (2010) Soybean tocopherol concentrations are affected by crop management. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58: 5495–5501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ujiie, A., Yamada, T., Fujimoto, K., Endo, Y. and Kitamura, K. (2005) Identification of soybean varieties with high α-tocopherol content. Breed. Sci. 55: 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Kanamaru, K., Li, W., Abe, J., Yamada, T. and Kitamura, K. (2007) Simultaneous accumulation of high contents of α-tocopherol and lutein is possible in seeds of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). Breed. Sci. 57: 297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. and Tuyen, D.D. (2012) Genetic studies on saline and sodic tolerances in soybean. Breed. Sci. 61: 559–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Luo, Y., Zhu, Y., Zhang, L., Zhang, W., Chen, R., Xu, M., Fan, Y. and Wang, L. (2013) GmTMT2a from soybean elevates the α-tocopherol content in corn and Arabidopsis. Transgenic Res. 22: 1021–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.