Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Abstract

Background:

Gynecomastia is a very common entity in men, and several authors estimate that approximately 50% to 70% of the male population has palpable breast tissue. Much has been published with regard to the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of gynecomastia. However, the anatomy of the gynecomastia tissue remains elusive to most surgeons.

Purpose:

The purpose of this article was to define the shape and consistency of the glandular tissue based on the vast experience of the senior author (MB).

Patients and Methods:

Between the years 1980 and 2014, a total of 5124 patients have been treated for gynecomastia with surgical excision, liposuction, or a combination of both. A total of 3130 specimens were collected with 5% of the cases being unilateral.

Results:

The specimens appear to have a unifying shape of a head, body, and tail. The head is semicircular in shape and is located more medially toward the sternum. The majority of the glandular tissue consists of a body located immediately deep to the nipple areolar complex. The tail appears to taper off of the body more laterally and toward the insertion of the pectoralis major muscle onto the humerus.

Conclusions:

This large series of gynecomastia specimens demonstrates a unique and unifying finding of a head, body, and tail. Understanding the anatomy of the gynecomastia gland can serve as a guide to gynecomastia surgeons to facilitate a more thorough exploration and subsequently sufficient gland excision.

Gynecomastia is a very common entity in men, and several authors estimate that approximately 50% to 70% of the male population have palpable breast tissue.1,2 Much has been published with regard to the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of gynecomastia.3–9 However, the anatomy of the gynecomastia tissue remains elusive to most surgeons, and many references omit any description of the male breast tissue.10–13 Attempts to define the contour and form of the male glandular tissue have been helpful in diagnosing gynecomastia on physical examination, but a more detailed description of the underlying mass is lacking.

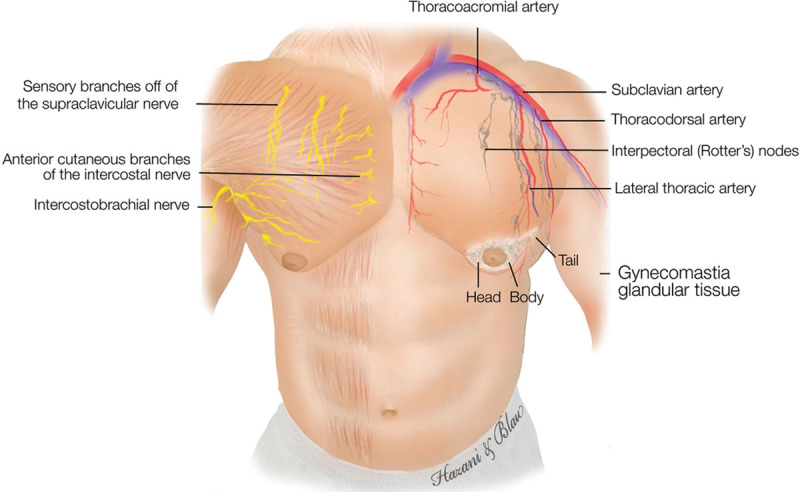

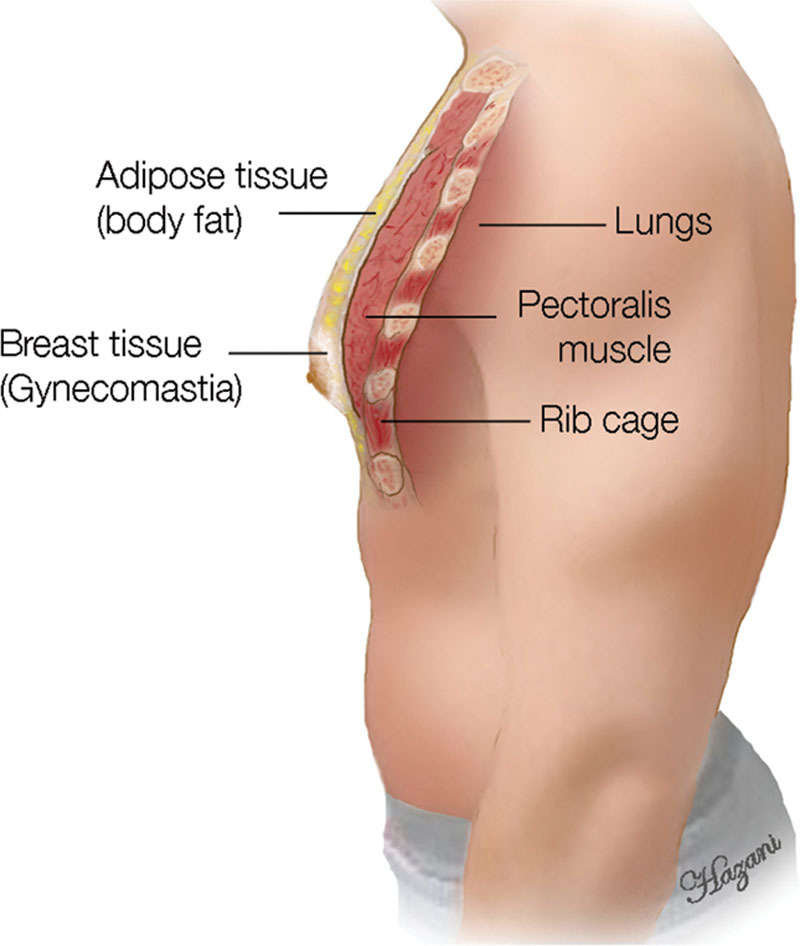

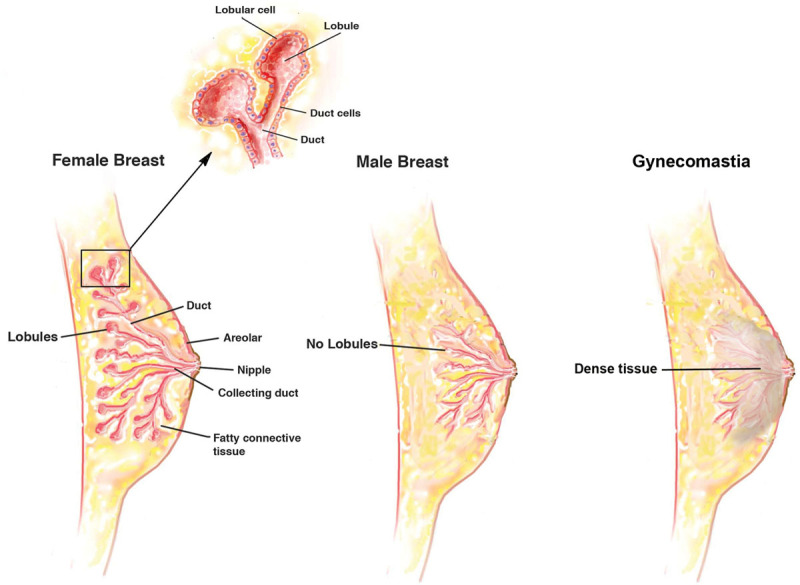

Ideally, the male chest should be flat with the pectoralis muscle accentuated. In the gynecomastia patient, the male breasts possess a more pyramidal shape with feminine features. Anatomically, the male breast, similar to the female breast, extends from the second through the sixth anterior ribs with the sternum as the medial border and the mid-axillary line demarcating the lateral extent (Figs. 1, 2). Healthy men typically have predominantly fatty tissue with few ducts and stroma,14 which is distinctly different from women’s breasts where ducts, stroma, and glandular tissue predominate (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Diagram illustrating the male chest with its associated arteries, gynecomastia glandular tissue, and nerves.

Fig. 2.

Side view of the male chest showing the different layers it contains starting from the rib cage, pectoralis muscle, adipose tissue, and then the glandular gynecomastia tissue.

Fig. 3.

Diagram illustrating the anatomical differences between the male and female breast. The male breast lacks lobules, and the gynecomastia tissue contains dense glandular tissue as shown.

We estimate that despite these well-established histological findings, the relatively high percentage of underresection or recurrence found in the literature7,8,15 after gynecomastia surgery may be attributed to our diminished understanding of the condition’s gross anatomy. The purpose of this article was to define the shape and consistency of the glandular tissue based on the vast experience of the senior author (MB).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

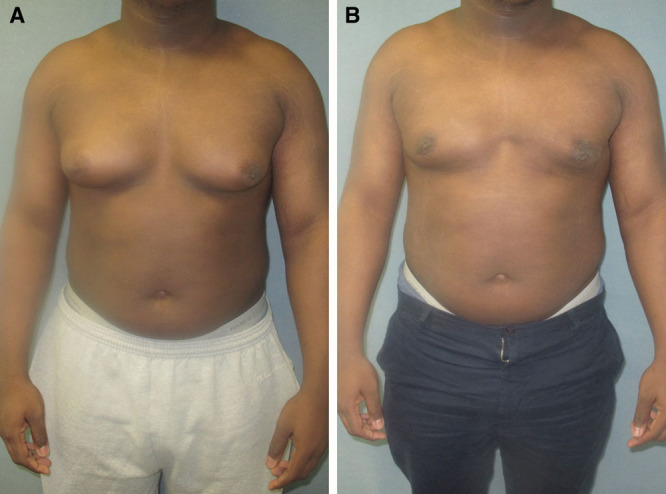

Between the years 1980 and 2014, a total of 5724 patients have been treated for gynecomastia with surgical excision, liposuction, or a combination of both (Figs. 4, 5). Of those, 1605 were bodybuilders or lean patients who underwent glandular excision only (Figs. 6, 7). The average age of these patients ranged from 11 to 69 years, with a mean of 27. A total of 10,715 specimens were collected with 5.4% of the cases being unilateral and 3.7% being performed with liposuction only.

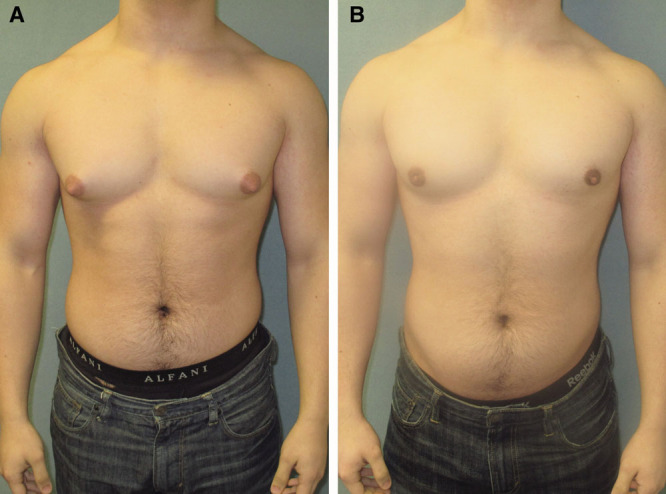

Fig. 4.

Images before (A) and after (B) gynecomastia surgery including direct excision and liposuction.

Fig. 5.

Images before (A) and after (B) gynecomastia surgery in a patient who underwent liposuction and gland excision.

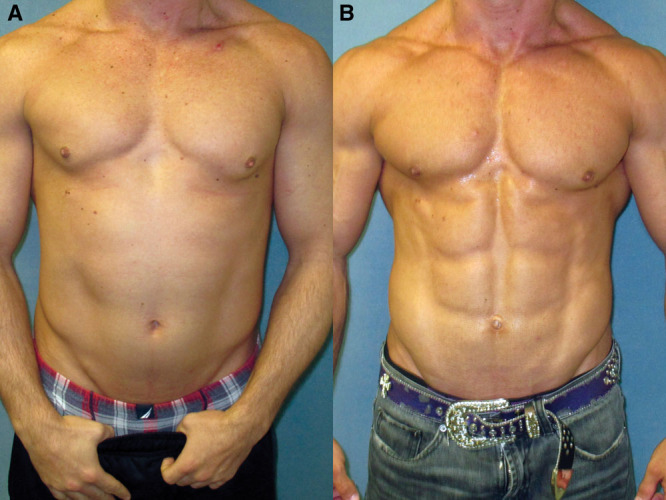

Fig. 6.

Images before (A) and after (B) gynecomastia surgery in a bodybuilder patient. This patient underwent direct excision of the glandular tissue.

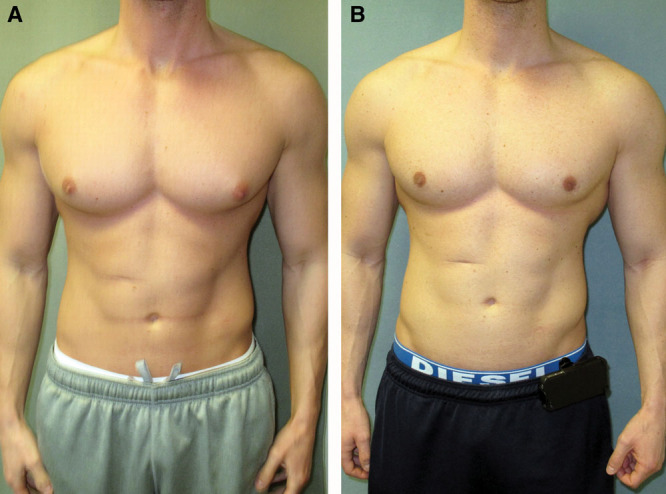

Fig. 7.

Images before (A) and after (B) gynecomastia surgery in a bodybuilder patient with direct excision. No liposuction was performed.

Technique

The glandular tissue was easily distinguished from the adipose tissue by its white glistering color versus the yellowish hue of the surrounding fatty tissue (Fig. 8). In all cases, an attempt has been made to remove the entire tissue in one piece. After excision, specimens were grossly inspected for their shape, consistency, and any irregularities. Tumescent solution consisting of lidocaine, Carbocaine (Sanofi, Paris, France), epinephrine, and bicarbonate mixed in 250 cc of normal saline solution was used in all cases. The operative technique consisted of a skin incision in the inferior periareolar location, 2.0 to 2.5 cm in length. Incisions were placed more laterally in an attempt to avoid medial scars (eg, a 4-o’clock to 7-o’clock position). Suction-assisted lipectomy was performed in only 5% of the cases using the contralateral breast periareolar incision as reported by Webster,11 Aiache,10 and Huang et al12 Indications for the use of liposuction were removal of peripheral fatty tissue in patients with mediocre physique. Professional bodybuilders have a much higher ratio of glandular to fatty tissue and required no liposuction in this study. In virtually all cases, a subcutaneous mastectomy was performed, leaving behind only 2 to 3 mm of glandular tissue under the skin (Fig. 9). In this manner, the nipple areolar complex (NAC) was flush with the contour of the pectoral muscle.

Fig. 8.

Complete excision of the glandular tissue via an inferior periareolar incision. Glandular tissue is represented by the glistering white tissue in contrast to the yellow subcutaneous fat, which appears superiorly in this image.

Fig. 9.

Complete excision of the gynecomastia tissue demonstrating the fibrous consistency of the specimen and the thinned out layer of areolar tissue after the subtotal excision of the glandular tissue.

In patients with low fat content, care was taken to remove all of the glandular tissue. Bodybuilders’ fat content is negligible compared with patients who have a high fat content where the surgeon may have to leave more of the glandular tissue. Sharp undermining was performed initially under direct vision to an area that extended to the area around the NAC. The remaining tissue was dissected bluntly when possible, while always staying within the confines of the outer border of the gland. On the deep layer, undermining tissues remained strictly above the pectoral fascia. Penetration of the fascia resulted in unnecessary hemorrhage and potential contour deformities. In addition, excessive bleeding was encountered more frequently with dissection on the far lateral aspect compared with the medial side of the gland. Meticulous hemostasis was achieved throughout with electrocautery. Care was taken to excise the entire gland as one entity, resulting in a single specimen. All glandular specimens were sent for pathologic analysis. This approach, which circumvents the need for piecemeal excisions, resulted in fewer complications and less operative time.

In 3% of the cases, a ¼-inch Penrose drain was placed through the surgical incision or the axilla for a total of 24 to 72 hours. Compression dressing was applied over the surgical site for 3 to 5 days. No antibiotics were prescribed postoperatively.

Postoperative instructions consisted of light activity with restricted range of motion of the shoulders for the first week. This is because of the attachment of the pectoral muscle to the proximal humerus. Movement of the pectoralis muscle often results in increased bleeding because of the excessive vascularity in bodybuilders. Motion is permitted in the elbow and wrist early in the postoperative period, as it is unrelated to the pectoralis muscle. Elastic compression dressing was applied over the chest for 5 days. Patients were instructed to keep the dressing intact and dry for that time, with minimal activities. Desk work is allowed after 3 to 5 days. More physical work was restricted for at least 1 to 2 weeks. Modified activity was resumed after 1-week follow-up with light, non–chest-related exercises for 2 to 3 weeks. Any exercise resulting in movement of the pectoralis muscles, including lifting, extension, or abduction of the shoulders, was discouraged. For example, patients were asked to wear button-up shirts to avoid arm lifting on the first week after surgery. A regular chest exercise regimen was resumed after 4 to 6 weeks.

Patients were followed up for a minimum of 12 months and up to 5 years. Satisfaction ratings were collected from all patients at a 1-year interval. Patients were contacted by phone or email over the remaining 3 to 4 years. Given the limited data in the literature regarding satisfaction rates in gynecomastia surgery, each patient was also asked to complete our Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations patient satisfaction survey. (See Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows an example of a patient satisfaction form provided for each patient at 1-year follow-up, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/A240.) These surveys were collected over the past 13 years.

RESULTS

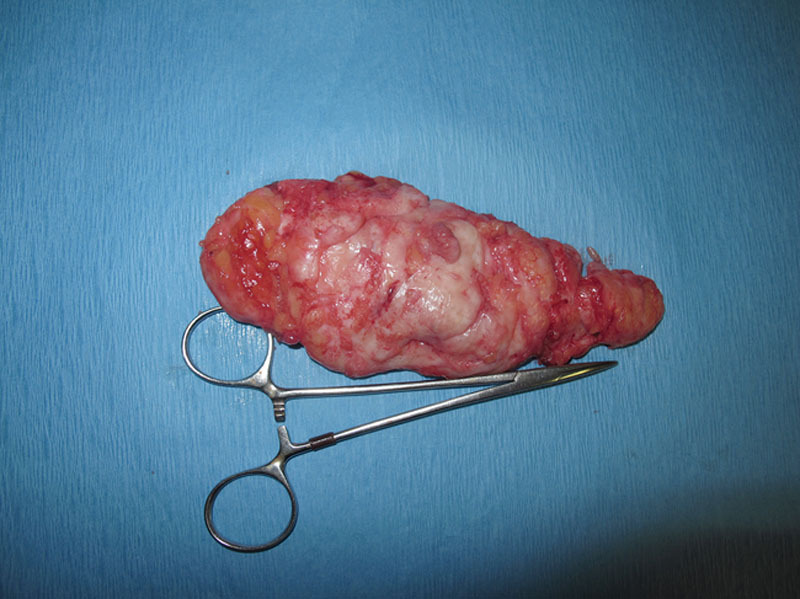

The specimens appear to have a unifying shape of a head, body, and tail (Fig. 10). The head is semicircular in shape and is located more medially toward the sternum. The majority of the glandular tissue consists of a body located immediately deep to the NAC. The tail appears to taper off of the body more laterally and toward the insertion of the pectoralis major muscle onto the humerus.

Fig. 10.

A specimen collected after surgical excision of gynecomastia from a bodybuilder. The specimen demonstrates the high glandular content of the tissue with its distinct shape of a head, body, and tail.

In all cases, the glandular tissue was inseparable from the NAC. This required direct sharp incision to complete the excision. Despite the aggressive resection of the gland at the NAC level, no cases of complete NAC necrosis were encountered. In 23 cases, which is 0.4% of the patients, we identified minor skin edge necrosis, which did not alter the aesthetic outcome. There were no instances of nipple necrosis or cases where skin excisions were necessary. Seromas occurred in 10% of patients. At the deep layer, the gland was separated from the pectoralis fascia by a soft areolar tissue in which undermining was achieved with manual blunt dissection. Undermining with a sharp instrument was performed in secondary or revision cases because of the dense adhesions.

Despite the varying degrees of tissue size or patient presentation, these findings have been consistent. Only 3 specimens contained a neoplastic growth, which did not distort the configuration of the gynecomastia tissue. In December of 2014, a young 32-year-old man was diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ that required bilateral mastectomies. Another patient in his early 60s was diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer found in the gynecomastia specimen after having prostatectomy in the past. The metastatic breast cancer had a poor prognosis and was sent to an oncologist and was treated by estrogen analogue, such as diethylstilboestrol.

DISCUSSION

The female breast is a well-studied gland with common features of ducts, lobules, fat, and stromal tissue.12 Unlike the female breast, male glandular tissue contains no lobules.14 Gynecomastia is the benign enlargement of this glandular tissue. The histologic classification of gynecomastia relies on the degree of stromal and ductal proliferation.5 Transient gynecomastia presents as a florid pattern with an increase in budding ducts and cellular stroma. The type of gynecomastia that many surgeons encounter in the operating room has likely been present for more than a year and, therefore, is more fibrous in nature. Extensive stromal fibrosis with minimal ductal proliferation is common in these cases.

On imaging, subareolar glandular tissue can be seen and at times can be markedly asymmetric. On ultrasound, hypoechoic to hyperechoic tissue is seen extending from behind the nipple. Gynecomastia can be avascular or hypervascular on color Doppler imaging depending on the stage of development, with more vascular flow seen in chronic cases of gynecomastia.14

For the clinician who is surgically removing the gynecomastia issue, these gross anatomic findings are crucial as they can assist in guiding the surgeon with his/her complete removal of the specimen. As the surgeon proceeds medially toward the sternum, dissection should be performed with care to remove the head of the glandular tissue, which can occasionally extend medially to the pectoralis muscle edge. Laterally, the gland can even extend further beyond the anterior axillary fold.

Care must be taken to avoid bleeding from the lateral thoracic artery and thoracoacromial artery and medially from the intercostal artery. Bleeding can be brisk and persistent as patients may lose up to 500 or 600 cc. In this study, every attempt was made to limit the extent of the scar to the original areolar incision. Thus far, there were only 2 cases in which there was a need to extend the incision to control bleeding. If a case of uncontrolled hemorrhage is encountered, we recommend that an extension of the original incision is created, or in rare cases, there may be a need to create an incision laterally to facilitate direct vision. Ultimately, aesthetics should not compromise the safety of the patient in any scenario.

In secondary cases, the gland has already been partially excised and the anatomy has been altered. Instead of searching for the classis configuration of a head, body, and tail, the surgeon must search for the remnants of the glandular tissue. Remnant tissue could be found anywhere and scarring and adhesion are the rule, not the exception. Bleeding is more common, operative time is extended, and the rate for postoperative complications is increased. These include seromas, hematomas, and contour deformities. Penetration of the pectoral fascia can cause similar outcome in the immediate postoperative period.

In bodybuilders, the described classic configuration of the glandular tissue exists but there is minimal fatty cushioning between the gland and fascia. It is easier to injure and penetrate the pectoralis fascia. Therefore, hematomas and seromas are also more common in these patients.8 In the senior author’s (MB) experience, bodybuilders with a particularly large glandular tissue were found to have a triad of symptoms in many cases. These include pain, tenderness, and rarely discharge, or a combination of those symptoms. Intraoperatively, it seems that some may have also had an inflammatory component to the surrounding tissue around the gland. We speculate that this can explain the existence of increased adhesions in these cases. Subsequently, dissection becomes more tedious with increased chance for bleeding.

In conclusion, we present a large series of gynecomastia specimens with a unifying finding of a head, body, and tail. Realization of this anatomy can serve as a guide to gynecomastia surgeons to facilitate a more thorough exploration and subsequently a sufficient amount of the gland excision. Despite our experience with extensive direct excision of the gland, we recommend for the novice surgeon to be less aggressive with the excision at the NAC layer. As additional experience is gained, it is expected that the clinical judgment of the surgeon will increase, and a proper amount of tissue can be excised without increasing the chance for tissue necrosis or recurrence.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Clickable URL citations appear in the text.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation, and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60671-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niewoehner CB, Nuttal FQ. Gynecomastia in a hospitalized male population. Am J Med. 1984;77:633–638. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90353-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braunstein GD. Clinical practice. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1229–1237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp070677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise GJ, Roorda AK, Kalter R. Male breast disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:255–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bannayan GA, Hajdu SI. Gynecomastia: clinicopathologic study of 351 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1972;57:431–437. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/57.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohrich RJ, Ha RY, Kenkel JM, et al. Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):909–923. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000042146.40379.25. discussion 924–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtiss EH. Gynecomastia: analysis of 159 patients and current recommendations for treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:740–753. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198705000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blau M, Hazani R. Correction of gynecomastia in body builders and patients with good physique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:425–432. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson RE, Kermott CA, Murad MH. Gynecomastia - evaluation and current treatment options. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:145–148. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S10181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Netter FH. Atlas of Human Anatomy. 8th ed. Summit, NJ: Ciba-Geigy Corporation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohen JW, Yokochi C. Color Atlas of Anatomy. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Igaku-Shoin Medical Publishers, Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agur AMR, Dalley AFI. 12th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abrahams P. The Atlas of the Human Body. San Diego: Thunder Bay Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iuanow E, Kettler M, Slanetz PJ. Spectrum of disease in the male breast. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W247–W259. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babigian A, Silverman RT. Management of gynecomastia due to use of anabolic steroids in bodybuilders. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:240–242. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200101000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]